Abstract

Enterovirus 68 (EV‐D68) was associated with mild to severe respiratory infections. In the last 4 years, circulation of different EV‐D68 strains has been documented worldwide. In this study, the phylogenetic characterization of nine EV‐D68 strains identified in patients in the 2010–2012 period and 12 additional EV‐D68 Italian strains previously identified in 2008 in Italy was described. From January 2010 to December 2012, a total of 889 respiratory specimens from 588 patients stayed or visited at the Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo were positive for HRV or HEV. Extracted nucleic acids were amplified by one‐step RT‐PCR with primer specific for VP1 region of EV‐D68 and purified positive PCR products were directly sequenced. Overall, 9/3736 (0.24%) patients were EV‐D68 positive. Of these, 7/9 (77.8%) were pediatric and two (22.2%) were adults. Five out of seven (71.4%) pediatric patients had lower respiratory tract infection with oxygen saturation <94%. Four cases were detected from August through October 2010, while five other cases from September through December 2012. The Italian EV‐D68 strains in 2008 belonged to clade A (n = 5) and clade C (n = 7). In 2010 all the Italian strains belonged to clade A (n = 4) and in 2012, four Italian strains belonged to clade B and one to clade A. In conclusion, we provide additional evidence supporting a role of EV‐D68 in severe respiratory infection in pediatric patients. In addition, all the three EV‐D68 clades circulating worldwide were identified in Italy in a 5‐year period of time. J. Med. Virol. 86:1590–1593, 2014. © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: enterovirus 68, respiratory infection, Italian strains, VP1 sequences

INTRODUCTION

Human enterovirus 68 (EV‐D68) belongs to the genus Enterovirus species D and was originally isolated in 1962 from patients with respiratory illness [Schieble et al., 1967]. Then, EV‐D68 was occasionally associated with respiratory syndromes ranging from mild to severe respiratory infections [Oberste et al., 2004; Jacobson et al., 2012; Khetsuriani et al., 2006]. More recently, circulation of different EV‐D68 strains has been documented worldwide [Imamura et al., 2011; Kaida et al., 2011; Rahamat‐Langendoen et al., 2011; Ikeda et al., 2012; Lauinger et al., 2012; Linsuwanon et al., 2012; Meijer et al., 2012; Piralla et al., 2012; Tokarz et al., 2012]. In particular, the circulation of three different EV‐D68 clades, defined by the phylogenetic analysis of VP1 sequences, has been recently reported [Linsuwanon et al., 2012; Meijer et al., 2012; Tokarz et al., 2012].

In a previous study, our group identified 12 EV‐D68 strains in respiratory samples from as many hospitalized patients in 2008 [Piralla et al., 2011, 2012]. In this study, the phylogenetic characterization of nine additional EV‐D68 strains identified in patients during the 2010–2012 period in Italy was described. In addition, the VP1 sequences of all 21 EV‐D68 strains [Piralla et al., 2011, 2012] detected so far in Italy were analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From January 2010 to December 2012, 6,211 respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal aspirates, nasal swabs and bronchoalveolar lavage) were collected from 3,736 patients (both inpatients and outpatients) who exhibited acute respiratory syndrome. The study was performed according to guidelines of the Institutional Review Board of the Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo on the use of biologic specimens for scientific purposes in keeping with Italian law (art.13 D.Lgs 196/2003), and after having obtained informed written consent.

A panel of respiratory viruses (including human respiratory syncytial virus A and B, human metapneumovirus A and B, human influenza virus type A and B, human parainfluenza viruses 1–4, human coronaviruses OC43, 229E, HKU1, and NL63, human rhinoviruses, and human enteroviruses) was investigated as described previously [Piralla et al., 2011, 2012]. A total of 889 samples from 588 patients were positive for HRV and HEV. Extracted nucleic acids were pooled in groups of 10 and amplified by one‐step RT‐PCR with primers specific for EV‐D68 (EV68‐36f 5′‐gtgggtcatgcccaacaacc‐3′ and EV68‐1r 5′‐attggatccctgggccttcaa) generating a 1,400 bp amplicon spanning the VP3 and 2A genes. Individual nucleic acid extracts from positive pools were re‐amplified with EV‐D68 specific RT‐PCR to identify positive patients. Purified PCR products were directly sequenced using the following primers: EV68‐36f, EV68‐37f 5′‐gccaatgttggctacgttacctg‐3′, EV68‐45f 5′‐caccatactcacaactgtggca‐3′, EV68‐2r 5′‐tggtgtcttccatgagcagcaa‐3′, EV68‐9r 5′‐actgccagtggaatgaatcctgc‐3′, and EV68‐1r. Cycle sequencing was performed using the BigDye Terminator Cycle‐Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with an ABI Prism 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

The sequences were assembled by using Sequencher software, version 4.6 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI) and aligned with MEGA software, version 5 [Tamura et al., 2011]. Phylogenetic analysis was performed online using the program PhyML [Guindon et al., 2010] and the TN93 + G + I nucleotide substitution model, which was selected with the hierarchical likelihood ratio test. The reliability of specific clades in the inferred tree was evaluated by using the SH‐like approximate likelihood ratio test (aLRT). Nucleotides dataset of the VP1 gene was obtained by including sequences from all available countries (France, Gambia, Japan, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Senegal, South Africa, and USA). The EV‐D68 sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (accession number: KC763157 to KC763177).

RESULTS

Overall, 9/3,736 (0.24%) patients were EV‐D68 positive. Seven out of nine (77.7%) were pediatric patients (median age 15 months; range 4 months to 6 years) and two (22.2%) were adults (Table I). Among pediatric patients, 5/7 (71.4%) had a lower respiratory tract infection with oxygen saturation <94%. In these patients, the median hospitalization duration was 6 days (range 4–12 days). The remaining pediatric patients 2/7 (28.6%), as well as the two adults had upper respiratory tract infections. Four cases were detected between August and October 2010, while five cases were detected between September and December 2012 (Table I). In all patients, EV‐D68 was the only virus detected in respiratory samples.

Table I.

Epidemiologic and Clinical Data of EV‐D68 Positive Patients During 2010–2012 in Italy

| Patient ID | Sampling date | Sex/age (years) | Diagnosis or signs | SaO2 a (%) | Underlying disease | Days of hospitalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31742/10 | Aug‐2010 | M/1 | Dyspnea, pneumonia | 93 | 6 | |

| 33658/10 | Oct‐2010 | M/6 | Fever, dyspnea | 88 | Dystrophy | 12 |

| 33707/10 | Oct‐2010 | M/25 | cough | None | ||

| 34800/10 | Oct‐2010 | M/56 | Fever, rhinorrhea | HSCT in 2007 | None | |

| 19391/12 | Sep‐2012 | F/14 | Fever, cough | Hodgkin lymphoma | 6 | |

| 20528/12 | Oct‐2012 | M/4 | Cough, asthma episode, wheezing, | 93 | 4 | |

| 22516/12 | Nov‐2012 | M/18 months | Cough, dyspnea, pneumonia | 92–94 | 7 | |

| 23695/12 | Nov‐2012 | F/1 | Fever, cough, respiratory distress | 92 | 5 | |

| 24518/12 | Dec‐2012 | M/4 months | Cough | None |

HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; SaO2, oxygen saturation.

SaO2 measured at time of hospital admission.

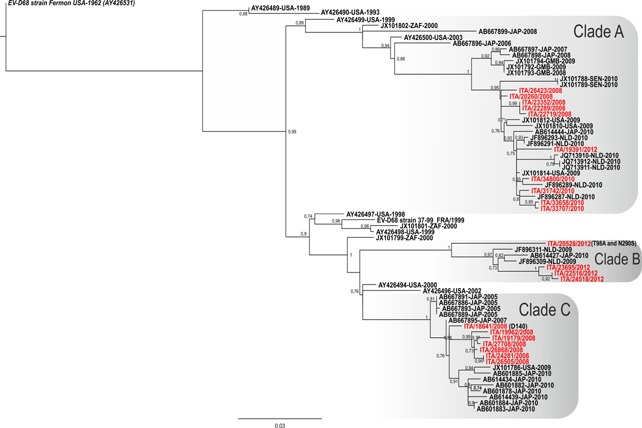

In addition to EV‐D68 strains identified during the 2010–2012 seasons, the VP1 gene was sequenced in 12 previously reported EV‐D68 Italian strains [Piralla et al., 2011, 2012]. The VP1 phylogenetic tree showed that all three EV‐D68 clades (referred to as clades A to C) circulated in our geographical area (Fig. 1). The Italian EV‐D68 strains in 2008 belonged to clade A (n = 5) and clade C (n = 7). In 2010, all of the Italian strains belonged to clade A (n = 4). Finally, in 2012, four Italian strains belonged to clade B and one to clade A. Of note, the strain 20528/12 clustered in a separate branch, with respect to the other Clade B sequences (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on the alignment of complete VP1 sequences of EV‐D68. The aLRT values >0.70 are indicated at nodes. Italian strains are reported in red. The EV‐D68 prototype strain Fermon is reported in italics. The reference strains are reported with accession number, country of origin, and year of collection.

A total of 41/306 (13.4%) amino acids changes were observed in Italian EV‐D68 sequences with respect to the prototype Fermon strains (accession number, AY426531). Of these, 15/41 (36.6%) were found in regions that are exposed on the outside of the virus in the folded VP1 capside protein (data not shown). The 20528/12 VP1 sequence had a nucleotide identity less than 94.9% with respect to other EV‐D68 clade B strains. In addition, this strain was characterized by the T98A, and N290S mutations, not observed previously in the VP1 sequences already available (up to 10 March 2013).

Three out of five (60.0%) patients with severe respiratory syndrome were infected by EV‐D68 belonging to clade B (strain 22516/12, 23695/12, and 20528/12) during the 2012 season. On the other hand, the other two patients were infected by EV‐D68 strains belonging to clade A (strain 31742/10 and 33658/10).

DISCUSSION

In recent years, the circulation of EV‐D68 has been reported worldwide [Kaida et al., 2011; Rahamat‐Langendoen et al., 2011; Lauinger et al., 2012; Linsuwanon et al., 2012; Meijer et al., 2012; Tokarz et al., 2012]. In this study, the prevalence of EV‐D68 positive patients was lower than those reported by other studies [Ikeda et al., 2012; Linsuwanon et al., 2012]. On the other hand, our study included both pediatric and adult patients while previous studies presented data only from pediatric patients.

In keeping with other studies, positive patients were primarily children and pediatric EV‐D68 infections were associated with more severe clinical symptoms with respect to adults [Khetsuriani et al., 2006; Imamura et al., 2011; Kaida et al., 2011; Rahamat‐Langendoen et al., 2011]. Although the etiologic role of EV‐D68 infections in severe respiratory infection remains to be fully elucidated, the absence of other agents in the respiratory samples in pediatric patients with lower respiratory syndromes suggests a significant pathogenic impact of EV‐D68.

All EV‐D68 strains identified in this study were observed in summer‐fall 2010 and in fall 2012. The circulation of EV‐D68 in 2010 was similar to that of EV‐D68 described in Japan, the Netherlands and the USA [Khetsuriani et al., 2006; Kaida et al., 2011; Rahamat‐Langendoen et al., 2011; Tokarz et al., 2012]. In addition, the circulation of EV‐D68 was reported also in 2012. The phylogenetic relationship between EV‐D68 strains circulating in 2008 [Piralla et al., 2011, 2012] and EV‐D68 circulating in 2010–2012 in Italy was investigated showing that strains circulating in 2008 and 2010 belonged to clades A and C, while most of strains in 2012 belonged to clade B. In the Italian EV‐D68 sequences, one third of amino acid changes were observed in VP1 regions corresponding to antigenic epitopes. In enteroviruses, these residues were reported to undergo a more rapid evolutionary changes compared with other genomic regions [Oberste et al., 1999]. In addition, as described previously, amino acid changes or deletion in the loop regions were involved in altered antibody recognition in enterovirus species [McPhee et al., 1994].

In conclusion, additional evidence supporting the role of EV‐D68 in severe respiratory infections in Italian hospitalized pediatric patients were provided. In addition, all the three EV‐D68 clades circulated in Italy during a 5‐year period.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniela Sartori for manuscript editing and Laurene Kelly for revision of the English.

REFERENCES

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum‐likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59:307–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T, Mizuta K, Abiko C, Aoki Y, Itagaki T, Katsushima F, Katsushima Y, Matsuzaki Y, Fuji N, Imamura T, Oshitani H, Noda M, Kimura H, Ahiko T. 2012. Acute respiratory infections due to enterovirus 68 in Yamagata, Japan between 2005 and 2010. Microbiol Immunol 56:139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura T, Fuji N, Suzuki A, Tamaki R, Saito M, Aniceto R, Galang H, Sombrero L, Lupisan S, Oshitani H. 2011. Enterovirus 68 among children with severe acute respiratory infection, the Philippines. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1430–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson LM, Redd JT, Schneider E, Lu X, Chern SW, Oberste MS, Erdman DD, Fischer GE, Armstrong GL, Kodani M, Montoya J, Magri JM, Cheek JE. 2012. Outbreak of lower respiratory tract illness associated with human enterovirus 68 among American Indian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 31:309–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida A, Kubo H, Sekiguchi J, Kohdera U, Togawa M, Shiomi M, Nishigaki T, Iritani N. 2011. Enterovirus 68 in children with acute respiratory tract infections, Osaka, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1494–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khetsuriani N, Lamonte‐Fowlkes A, Oberst S, Pallansch MA. 2006. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Enterovirus surveillance—United States, 1970–2005. MMWR Surveill Summ 55:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauinger IL, Bible JM, Halligan EP, Aarons EJ, MacMahon E, Tong CY. 2012. Lineages, sub‐lineages and variants of enterovirus 68 in recent outbreaks. PLoS ONE 7:e36005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsuwanon P, Puenpa J, Suwannakarn K, Auksornkitti V, Vichiwattana P, Korkong S, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan Y. 2012. Molecular epidemiology and evolution of human enterovirus serotype 68 in Thailand, 2006–2011. PLoS ONE 7:e35190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee F, Zell R, Reimann BY, Hofschneider PH, Kandolf R. 1994. Characterization of the N‐terminal part of the neutralizing antigenic site I of coxsackievirus B4 by mutation analysis of antigen chimeras. Virus Res 34:139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer A, van der Sanden S, Snijders BEP, Jaramillo‐Gutierrez G, Bont L, van der Ent CK, Overduin P, Jenny SL, Jusic E, van der Avoort HGAM, Smith GJD, Donker GA, Koopmans MPG. 2012. Emergence and epidemic occurrence of enterovirus 68 respiratory infections in The Netherlands in 2010. Virology 423:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberste MS, Maher K, Kilpatrick DR, Pallansch MA. 1999. Molecular evolution of human enteroviruses: correlation of serotype with VP1 sequence and application to picornavirus classification. J Virol 73:1941–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberste MS, Maher K, Schnurr D, Flemister MR, Lovchik JC, Peters H, Sessions W, Kirk C, Chatterjee N, Fuller S, Hanauer JM, Pallansch MA. 2004. Enterovirus 68 is associated with respiratory illness and shares biological features with both the enteroviruses and the rhinoviruses. J Gen Virol 85:2577–2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piralla A, Baldanti F, Gerna G. 2011. Phylogenetic patterns of human respiratory picornavirus species, including the newly identified group C rhinoviruses, during a 1‐year surveillance of a hospitalized patient population in Italy. J Clin Microbiol 49:373–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piralla A, Lilleri D, Sarasini A, Marchi A, Zecca M, Stronati M, Baldanti F, Gerna G. 2012. Human rhinovirus and human respiratory enterovirus (EV68 and EV104) infections in hospitalized patients in Italy, 2008–2009. Diagn Microb Infect Dis 73:162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahamat‐Langendoen J, Riezebos‐Brilman A, Borger R, van der Heide R, Brandenburg A, Schölvinck E, Niesters HGM. 2011. Upsurge of human enterovirus 68 infections in patients with severe respiratory tract infections. J Clin Virol 52:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieble JH, Fox VL, Lennette EH. 1967. A probable new human picornavirus associated with respiratory diseases. Am J Epidemiol 85:297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokarz R, Firth C, Madhi SA, Howie SRC, Wu WY, Sall AA, Haq S, Briese T, Lipkin WI. 2012. Worldwide emergence of multiple clades of enterovirus 68. J Gen Virol 93:1952–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]