Abstract

Aims and objectives

To explore the difficulties and strategies regarding guideline implementation among emergency nurses.

Background

Emerging infectious diseases remain an underlying source of global health concern. Guidelines for accident and emergency departments would require adjustments for infectious disease management. However, disparities between guidelines and nurses' practice are frequently reported, which undermines the implementation of these guidelines into practice. This article explores the experience of frontline emergency nurses regarding guideline implementation and provides an in‐depth account of their strategies in bridging guideline‐practice gaps.

Design

A qualitative descriptive design was used.

Methods

Semi‐structured, face‐to‐face, individual interviews were conducted between November 2013–May 2014. A purposive sample of 12 frontline emergency nurses from five accident and emergency departments in Hong Kong were recruited. The audio‐recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed with a qualitative content analysis approach.

Results

Four key categories associated with guideline‐practice gaps emerged, including getting work done, adapting to accelerated infection control measures, compromising care standards and resolving competing clinical judgments across collaborating departments. The results illustrate that the guideline‐practice gaps could be associated with inadequate provision of corresponding organisational supports after guidelines are established.

Conclusions

The nurses' experiences have uncovered the difficulties in the implementation of guidelines in emergency care settings and the corresponding strategies used to address these problems. The nurses' experiences reflect their endeavour in adjusting accordingly and adapting themselves to their circumstances in the face of unfeasible guidelines.

Relevance to clinical practice

It is important to customise guidelines to the needs of frontline nurses. Maintaining cross‐departmental consensus on guideline interpretation and operation is also indicated as an important component for effective guideline implementation.

Keywords: accident and emergency department, emergency care setting, emergency nurse, guideline‐practice gap, infectious disease outbreak, outbreak management

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

It is demonstrated that the guideline‐practice gap that emergency nurses face is intertwined with issues regarding environmental constraints, inadequate resources and suboptimal communication.

The findings indicate the importance of enhancing intraorganisational communication over the course of an epidemic event to maintain cross‐departmental consensus on guideline interpretation and operation.

A bottom‐up approach should be considered in the development of future guidelines so as to better capture the imperative needs of frontline nurses and other personnel.

Introduction

Among the many challenges to public health, infectious diseases remain an underlying source of global health concern that continues to garner considerable local and national attention (Wong et al. 2012). Despite remarkable advances in the efficacy of preventive and curative measures against infection, these diseases still account for approximately 10 million deaths worldwide per year and impose an onerous burden on global health (Morse 2012). In recent decades, emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) have created an increasing impetus for reinforcement of infectious disease preparedness planning. This group of diseases, which refers to newly recognised infectious diseases or known infections that present with an increased incidence and geographic range in the recent past or foreseeable future [World Health Organization (WHO 2005)], represent the majority of recent large‐scale public health emergencies, including the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in 2003, the H1N1 influenza (swine flu) pandemic in 2009 (Leppin & Aro 2009) and the Ebola virus disease epidemic in 2014 (Chertow et al. 2014). Recently, a sharp increase in human infections from a new strain of coronavirus, the Middle East respiratory syndrome, has been reported, which poses a new challenge to the global health care system and the capacity of institutions regarding outbreak management (Cowling et al. 2015).

Background

By serving as the interface between the health care sector and the community, accident and emergency departments (AEDs) take on a wide role regarding actively participation in planning and responding to public health threats from EIDs (Sugerman et al. 2011). Emergency nurses, in view of the frequency and intensity of close patient contact, are in an ideal position for disease surveillance. Their involvement in infection control and disease prevention can also help to reduce the risk of disease exposure of the wider population in the community (Lam & Hung 2013). With the increasing prevalence of EIDs, the workflows of AEDs would require adjustments to meet the altered health care demands and targets. Major changes to the practice of emergency nursing care delivery are often incorporated into workflow modifications to enhance disease surveillance and infection control (Blachere et al. 2009). With a view to assist emergency nurses to embed these changes into their everyday work, guidelines are formulated and implemented in routine practice. These guidelines can provide recommendations and instructions to inform emergency nurses' judgment regarding logistic arrangements, infection control practices, service standards and cross‐departmental collaboration, which are crucial elements in efficient epidemic management (Carter et al. 2014).

However, disparities between guideline adherence and nurses' practice are frequently reported to undermine the successful implementation of guidelines into practice. Nichol et al. (2008) noted that the general compliance of nurses with newly introduced guidelines and protocols was usually low, which might be related to their reluctance to change their usual practice. More specifically, there was a breach in safety procedures and infection control. Mounting evidence shows that adherence to guidelines regarding infection control, such as hand hygiene and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), is seriously inadequate among nurses in a variety of health care settings (Pan et al. 2008, Efstathiou et al. 2011). Notwithstanding, studies have mainly emphasised the adherence to safety procedures in infection control; detailed studies investigating compliance to infection control guidelines on the rearrangement of workflow and routine practice are sparse. Also, because most of the investigations to date have studied guideline implementation in general care settings, issues regarding guideline adherence and nurses' practice in infectious disease management in emergency care settings remain poorly understood (Carter et al. 2014). In seeking to ensure a timely and appropriate response to impending outbreaks, this study was conducted to offer a sound understanding of the unique features of guideline implementation in the course of an epidemic event in an emergency care context.

Methods

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore the experience of frontline emergency nurses regarding guideline implementation and to provide an in‐depth account of their corresponding strategies in facilitating guideline adherence.

Design

This study employed a qualitative descriptive design, a method of naturalistic inquiry intended to yield an in‐depth understanding of phenomena embedded within human contexts (Sandelowski 2000). The process of gathering detailed information offers insights into the complexity and diversity of individuals' experiences. The broader scope covered by qualitative strategies can then be used to extract rich descriptions of the individuals' perceptions and behaviours within the content and context of the phenomenon of interest (Creswell 2012). Inasmuch as qualitative investigations can facilitate the illumination of individualised perspectives throughout a process, it is considered to be particularly appropriate in establishing the extent to which a programme or a protocol has been appropriately implemented (Patton 2015). Therefore, a qualitative research design was chosen as the method of inquiry in this study to delineate an in‐depth exploration of emergency nurses' perceptions and behaviours in guideline implementation.

Participants

This study was conducted in Hong Kong between November 2013–May 2014. Five local acute care hospital sites were selected to involve those with isolation facilities of a high standard and those that offered a full range of emergency services. Frontline emergency nurses were recruited from the AEDs of the five hospitals with a purposive sampling technique. This sampling strategy entails the selection of participants who have the potential to provide rich and relevant information pertinent to the study (Streubert & Carpenter 1995). Criteria for participant selection were as follows: (1) at least one year of work experience in emergency nursing services, (2) involvement in frontline patient care, and (3) willingness to share his or her experiences in responding to guideline implementation in the management of EIDs.

Data collection

Semi‐structured, face‐to‐face, individual interviews were conducted to explore the participants’ experiences in implementing guidelines regarding EID management into practice in an emergency care context. Interviews are widely used in qualitative research as an interactive and flexible method that allows researchers to gather information from participants’ narratives and conversations (Chenitz & Swanson 1986, Winpenny & Glass 2000). Over the course of a semi‐structured interview, that is, an interview without a rigid set of close‐ended questions for the participants, flexibility is granted to informants to express their perspectives from different dimensions (Robertson & Boyle 1984, Minichiello et al. 1990). Nonetheless, an interview agenda was developed to guide the theme of coverage to maintain a consistency of focus throughout the interviews (Rose 1994, Briggs 2000). The participants were allowed to select the venues for the interviews on the premise of privacy and confidentiality. Interviews were conducted in Chinese and began with a general question: ‘Please tell me about your experience in upholding the guidelines for management of emerging infectious diseases.’ Subsequent open‐ended questions were asked by the interviewers according to the interview agenda. Probing questions were asked to clarify statements that were vague or ambiguous (Barriball & While 1994). All interviews were audio‐recorded with the participants’ permission. The interviews lasted around an hour.

Data analysis

The digitally recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim for analysis. In addition to the actual words in the interviews, interruptions and significant pauses were accurately recorded in the transcript to express the interviewees' sentiments. Each transcript was compared against the audiotape of the interview at least once to confirm the completeness and literal accuracy of the verbatim transcription. The verbatim transcripts were then interpreted manually using inductive content analysis, an approach frequently adopted for qualitative data interpretation (Schreier 2012). This approach involves identification and refinement of categories inherent in the data and is well‐suited to provide a rich and nuanced account of research findings without obscuring data (Thomas 2006).

The analytic procedure was informed by the qualitative content analysis approach, which consists of three phases: open coding, creation of categories and abstraction (Elo & Kyngäs 2008). The open coding phase commenced with detailed scrutiny of each interview transcript to familiarise the researchers with their contents. An indexing scheme was initiated by breaking the information down into discrete segments of meaning units. Once the meaning units emerged, they were coded by labelling them with their representative characteristics and relevance regarding the phenomenon of interest.

After the open coding phase, categories were created by sorting and collating codes that shared similar sequences and features. Headings were assigned to the categories to succinctly describe the conceptual nature. In this phase, links among categories were established according to common meanings. Refined categories were then integrated that conveyed a broader understanding of the phenomenon of the guideline‐practice gaps that emergency nurses face.

The abstraction phase, the final step of inductive content analysis, was intended to develop a superordinate category at a higher level of abstraction (Dey 1993). The category was developed on the premise of natural theoretical connections to other categories. To accomplish this, the existing categories were reviewed, revised and refined to generate an overall model that consisted of a network that included a well‐defined superordinate category and subordinate categories (Robson 2002).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Departmental Research Committee, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Written and verbal information about the study's purpose and procedures was provided to the participants. The emergency nurses were invited to participate without any coercion. Written consent was obtained from the participants to indicate their permission for participation. The participants were informed about their right to cease, postpone or withdraw from the study at any time. Throughout the study, the confidentiality of the participants' personal information was guaranteed. The data in this paper are presented anonymously, and any information that could identify the participants' identities has been removed.

Results

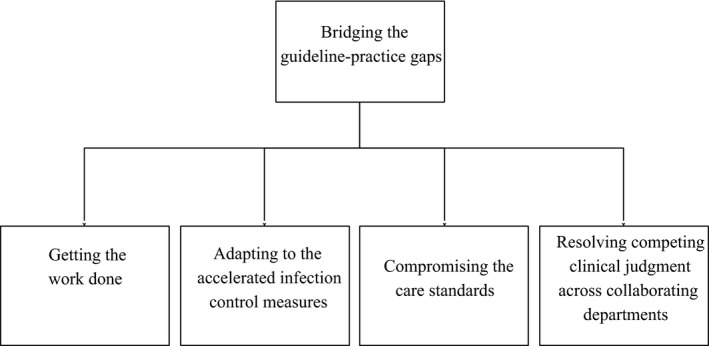

Twelve emergency nurses participated in this study. Table 1 summarises their demographic characteristics. In the participants' accounts of the events surrounding guideline implementation, four key categories associated with the guideline‐practice gap emerged: getting work done, adapting to accelerated infection control measures, compromising care standards and resolving competing clinical judgments across collaborating departments. Within each theme, the participants described the nature of the events and illustrated them with examples from their clinical experience. Figure 1 presents a model of the categories regarding the guideline‐practice gaps that face emergency nurses in the management of EIDs.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Total (n = 12) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 (58·3) |

| Female | 5 (41·7) |

| Age | |

| 21–25 | 3 (25) |

| 26–30 | 5 (41·7) |

| 31–35 | 2 (16·7) |

| 36–40 | 1 (8·3) |

| 41–45 | 1 (8·3) |

| Rank | |

| Registered nurse | 11 (91·7) |

| Nursing officer | 1 (8·3) |

| Years working in AED | |

| 1–5 | 9 (75) |

| 6–10 | 1 (8·3) |

| 11–15 | 1 (8·3) |

| 16–20 | 1 (8·3) |

AED, accident and emergency departments

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Figure 1.

Categories regarding the guideline‐practice gaps that face emergency nurses in the management of EIDs. EID, emerging infectious diseases.

Getting work done

In managing the imminent threat of EIDs, the participants’ descriptions of their experiences revealed the futility of the new guidelines in smoothening staff workflow and patient services. The majority of participants perceived that hospital administrators had merely adopted stopgap measures in tackling workflow issues, instead of considering and providing comprehensive solutions for effective and efficient workflow. One participant vividly described the existing workflow arrangement as a ‘piecemeal’ approach, in which ‘treat the head when the head aches, treat the foot when the foot hurts’ (Nurse 2). This sentiment was echoed by another participant, who pointed out the lack of discretion for workflow planning as follows:

A new ward was opened to handle the patient surge caused by EIDs. For the workflow arrangement and guidelines of the ward, there was next to no planning by the administrators on feasibility before application. Various problems arose after implementing those guidelines, including staff reallocation and patient logistics… this could have been avoided if the flows and guidelines were planned more wisely. (Nurse 6)

When asked about barriers to applying the recommended guidelines to optimise staff workflow, a common view among the participants was that the guidelines were idealised and impracticable in actual situations. One participant stated that the administrators were unable to evaluate the feasibility of the guidelines, unless they could ‘be here and experience how poorly the workflow guidelines were designed’ (Nurse 6). Another participant pointed out that although considerable efforts had been pledged in formulating hypothetical guidelines, they were no more than a paper exercise without considering possible obstacles in real world situations:

The planned guidelines could be extremely comprehensive, but once they were to be applied in clinical settings, unexpected flaws and limitations emerged that could only be discovered by frontline staff. Maybe there is a need to balance theory and practice in clinical settings, and this is the difficulty we are facing. (Nurse 3)

In delineating their strategies to address the need for practical guidance on staff workflow and patient logistics, most participants valued the importance of approaching senior colleagues for advice. The participants regarded assistance from senior colleagues to be helpful and practical because it originated from their experience in similar situations. As one participant described:

The advice from senior colleagues is very helpful… their advice could help me to make decisions on issues such as where and how to settle suspected infectious patients… I can be more content with my decision and feel more confident about doing it. (Nurse 10)

Regarding this issue, a participant with more than 20 years of experience in the field of emergency nursing revealed his opinion as follows:

I will not depend on the authority to notify me how to do [things]… some good practices are integrated in daily practice; they are parts of my work habits… I would like to teach these good practices to newcomers. (Nurse 6)

Adapting to accelerated infection control measures

To prevent nosocomial infections, more stringent infection control guidelines are established to tie in with the elevated incidences of EID infection. All of the participants valued the relevance of these accelerated infection control measures in protecting health care personnel and patients against EIDs. Nonetheless, in describing their adherence to the enforced infection control measures, the participants reported noncompliance with the recommendations. The majority of them reported that proper adherence to the standards mentioned in the infection control guidelines could be cumbersome for routine patient care. A participant commented that:

The new recommendations are surely bothersome… I am required to wear full gear PPE before approaching patients with suspected infection… if an isolated patient has a fever and requires medications, I will have to take off the PPE right after leaving the isolation room, get the medication required, and put on the PPE again before entering the room. Doing so is not difficult, but troublesome. (Nurse 11)

Some participants further expressed difficulty in compliance with the recommendations, particularly when they were in charge of admission triage. For example, one participant stated:

The guidelines require us to perform hand hygiene every time after triaging a patient. However, it is impossible, definitely impossible. There are always so many patients queuing for triage assessment, I am not able to spare time to clean my hands in between…even though hand washing or sanitization facilities are all around. (Nurse 4)

Many of the participants identified the enormous workload that resulted from the patient upsurge as the primary obstacle that impeded emergency nurses from following the infection control guidelines laid down by administrators. They explained that the guidelines had added extra tasks to the prevailing intense workload. When depicting the challenge with hand hygiene compliance during peak workload period, a participant described:

You just do not have the time to clean your hands properly. It might take only a minute for hand washing, but when there are too many tasks requiring you to finish at once, every single minute counts… I would rather spend time on other more important work. (Nurse 7)

Despite the difficulties in abiding to the standardised infection control practices, the participants revealed their strategies to prevent infections and control the spread of the EID. Several participants stated that they would maintain prudence in the course of infection control practice in situations if an elevated risk for infection was anticipated. For example, one participant described how he assessed the infectious status of patients as follows:

An opinion on patients' infectious status would be formed from initial assessment… for patients who had no relevant travel and contact history of the disease, the risk for them to be infected should be minimal… for patients who had recent travel history to outbreak‐affected areas or who presented with laborious breathing, we would be particularly cautious and more aware of infection control practices. (Nurse 9)

Another participant illustrated that she would adhere more closely to precautionary measures when performing high‐risk nursing procedures:

The situation requires us to choose between options… we opt to pay more careful attention to infection control instructions in high‐risk procedures. For example, we will be more cautious about hand hygiene after performing sputum suctioning… and would put PPE and a face‐shield on… regardless of how busy we are. (Nurse 4)

Compromising care standards

Contemplation of the participants' experiences highlights that continuous maintenance of the same rigorous standards and high quality of patient care is one of the most challenging tasks in epidemic management, particularly because the new policies and regulations to confront EIDs could adversely affect the standard of service delivery. Although extensive attention had been drawn to issues related to infection control and the management of patients with suspected infections, several participants raised concern about overlooking the continuing need for provision of routine emergency services. A participant illustrated that:

The recently introduced guidelines could affect our daily routine practice to a certain extent. Following the instructions provided would be onerous within my working area… I am concerned about whether the care I provide to patients is inappropriate… it should not be an issue of negligence… patients were not harmed… the care perhaps was just suboptimal. (Nurse 1)

This participant further described how the operation of resuscitation rooms was influenced by the needs for quarantine measures for suspected patients:

When patients were suspected to be contagious and required isolation, the resuscitation rooms would be used for the purpose… because only the specifications of the resuscitation rooms could fulfill the isolation requirements regarding the ventilation system… the problem is, there are only two resuscitation rooms in our department. Once the rooms were occupied for patient isolation, patients who required immediate lifesaving and resuscitation services could be in trouble. (Nurse 1)

Comments regarding insufficient infection control infrastructure were echoed by other participants. Some nurses cited that lacking the required facilities to implement the recommended practices not merely influenced guideline adherence regarding EID management, but also undermined the standards for provision of care service. One participant illustrated the difficulty in segregating patients with symptomatic infection from other patients as follows:

According to the guideline, patients who present with fever or symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection are required to be assigned together in a waiting area… the waiting area is too small and therefore is always crowded and congested… because not all of the suspected patients are actually infected, this could pose the risk for cross infection among these patients. (Nurse 4)

The participants' expressions showed a sense of responsibility for safeguarding the quality of health care. Despite implementing guidelines that could sometimes be perceived as ineffective in ensuring patient safety, most of the participants emphasised their intention to promote quality care. One participant described the joint endeavour of colleagues in his department in striving for a high standard of practice and care:

Carrying out the recommended policies have impacted our practice in many aspects… still, we all have the common goal in improving the quality of nursing care… we are willing to work more for the sake of patients… we will help each other to promote quality care. (Nurse 9)

Resolving competing clinical judgments across collaborating departments

Despite cooperative efforts among emergency nurses to overcome problematic issues that arose from the new regulations as mentioned above, concerns over cross‐departmental collaboration were manifested frequently in the participants' descriptions. Most participants expressed that staff from general wards might overdo vigilance against EIDs. A participant offered a vivid example to illustrate his views about the conflict in admitting patients on to wards:

A pediatric patient attended our department and claimed that he had been playing with poultry… his mother explained that he had chased a chicken without touching it… but the staff in the receiving general pediatric ward were so anxious about whether the patient had been infected with avian flu and kept challenging our decision…asked us irrelevant questions such as how fast the chicken was running… they were just over‐exaggerated, made every admission complicated, created unnecessary troubles. (Nurse 6)

In addition, the participants revealed the controversy associated with the divergence of understandings regarding admission guidelines between staff from AEDs and staff from general wards. Several participants claimed that staff from other departments had queried and even disputed their judgments regarding whether a patient should be admitted to an isolation ward or to a general ward. A nurse shared his experience with rejection when tried to admit a noncontagious patient on to a general ward:

I once had arranged admission for a non‐infectious patient who previously had been suspected for infection. Although the patient was confirmed to be clean (non‐infectious), the staff from the receiving medical ward had become very sensitive, challenged the admission criteria in our department and refused to receive the patient… at last the patient had to be admitted to an isolation ward. (Nurse 6)

In addressing the contentious issue concerning guideline comprehension and implementation, some participants emphasised the importance of organisational support. They highlighted that seeking assistance from hospital administrators was the most effective strategy to resolve conflicts between departments. For example, one participant valued the efforts of the manager in his department in coordinating and communicating with other departments:

It is important to achieve consensus among departments in managing new diseases (EIDs)… we would give feedback on our difficulties or arguments at work to the manager. She would voice our opinions to the authority and attempt to negotiate on our behalf. We can see her intention to help the frontline staff. (Nurse 9)

However, although some participants felt that administrators were supportive, others did not considered managerial responsiveness to be in alignment with their expectations. A participant offered the following opinion:

The administration seldom communicates with the frontline… they would approach you only when you have complained… even they notice the problem we are now facing, [but] they are not going to help us. Seeking help from them always ends in vain. (Nurse 8)

Discussion

The findings from this study make an important contribution by indicating the gaps between the guidelines and clinical practices encountered by emergency nurses in the management of EIDs. The results illustrate that the guideline‐practice gaps can be accounted for by inadequate provision of corresponding administrative and organisational support, in terms of manpower, facilities and policies, after the launch of the guidelines in practice. These findings are consistent with those in the literature that show that transferring guidelines into clinical practice is greatly influenced by the practice environment, including the availability of resources and leadership responsiveness (Graham et al. 2004). In fact, the perceived impracticality of the guidelines was repeatedly cited by the participants, who highlighted the fundamental shortcomings on administrative leadership in showing responsiveness to the constituent concerns of the environmental constraints in the workplace. These findings are in agreement with those of May et al. (2014), who reviewed the constituents of implementation of nursing clinical practice guidelines in the literature. Their review summarised the results from the studies of Ploeg et al. (2007) and Yagasaki and Komatsu (2011), which identified that the adherence of guidelines among nurses could be adversely influenced and the applicability of integrating guidelines was impeded by constraints in clinical settings. The limited applicability of guidelines as reported in the current study could be explained by the top‐down planning approach that is commonly adopted in various health care organisations for guideline formulation (Mintzberg 2012). This top‐down approach refers to a strategy of decision‐making regarding processes that involves the participation only of administrative personnel at the senior level (Meslin 2009). Without the participation of frontline personnel, the imposed guidelines and policies often deviate from their expectations and capacities and limit the uptake of guidelines into workflow (Ploeg et al. 2007). Therefore, the need for subsequent evaluation of the processes and outcomes regarding guideline implementation are highlighted to examine the feasibility and workability of guidelines in existing situations.

Among the various environmental constraints that challenge guideline implementation in workplaces among emergency nurses, the aspects of time and facility constraints have received considerable attention. The participants in this study indicated that time constraints imposed by their excessive workload interfered with their engagement with guidelines such as hand hygiene practices and PPE usage. In accordance with the present results, previous studies have shown that heavy workloads and inadequate staffing could inhibit nurses from implementing new guidelines into practice, inasmuch as the guidelines produced additional work and duties for them (Ploeg et al. 2007, Lam & Hung 2013, Matthew‐Maich et al. 2013). In addition to time constraints, facility constraints, particularly regarding respiratory isolation rooms in AEDs, were seen by the participants as another major barrier to successful guideline implementation. Although the importance of spatial separation in controlling respiratory contagion was generally acknowledged by the participants, the difficulties inherent in isolation facility limitations had inhibited them from implementing quarantine measures for suspected patients. This finding is comparable to that of Martel et al. (2013), in which a low compliance rate of emergency nurses to appropriate patient isolation was identified as a result of the constrained practice environment. Furthermore, it is somewhat surprising to reveal from the present findings that access to emergency care for patients in critical condition could be impeded because resuscitation facilities are occupied for respiratory isolation. Although the dual use of facilities is a seemingly helpful method to enhance the effective use of available resources, particularly in the management of unexpected patient upsurges (Hick et al. 2004), prudent consideration of facility planning is essential for hospital administrators to prevent affecting the usual standards of health care services. Thus, clinical guidelines should be devised in conjunction with surge planning to enhance patient care surge capacity during the management of large‐scale epidemic events.

In addition to constraints from environmental contexts regarding limited staffing and facility resources, the participants in this study pointed to several issues of guideline‐practice gap relating to intraorganisational coordination, including a lack of cross‐departmental consensus on in the interpretation and operation of admission guidelines and discrepancies in the determination of patients' infectious status. Consistent with this finding, much of the current literature on guideline implementation pays particular attention to organisational efforts in coordination and promotion of uptake of practice guidelines among health care personnel (Ploeg et al. 2007, Farrar & Piot 2014). In fact, it has been suggested that organisational coordination supports successful implementation not merely in articulating the definitions and standards of the guidelines, but by also creating buy‐in for the guidelines by establishing communication between units and departments (Matthew‐Maich et al. 2013). These findings were complemented by the study of Choi et al. (2011), which noted that managerial support, in terms of effective communication and coordination with subordinates, was of particular importance in promoting nursing practice in chaotic situations, such as infectious disease outbreaks. In the same vein, participants in this study valued assistance from departmental management in conveying their concerns regarding guideline implementation on behalf of the frontline personnel, and they emphasised the importance of effective communication between frontline personnel and the administration in successful guideline implementation. The findings offer needed insight into the administration's role in enhancing guideline implementation by reinforcing intraorganisational and interorganisational coordination.

The findings also suggest that experienced nurses might be more resourceful in managing conflicts and uncertainties over the uptake of guidelines, which signifies the association between problem‐solving skills and clinical experience. In this context, there are similarities between the opinions expressed by the participants in this study and those described by Pretz and Folse (2011). These authors explained that experienced nurses might have developed a structured knowledge base by accumulation of clinical experience, which helped them adapt to novel situations. As implied in the findings of this study, the participants took into account their clinical experience in responding to the problematic issue of guideline implementation, which suggest the relevance of tacit knowledge – that is, knowledge based upon individual experiences, insights and intuitions – in clinical judgment. Indeed, the decision‐making processes of nurses frequently involve the interaction of tacit and explicit knowledge (Kothari et al. 2012). It became evident throughout the participants' descriptions that the application of tacit and explicit knowledge is one of the most decisive parameters of their adaptive capacity in bridging the guideline‐practice gaps for management of an epidemic event. Although there is mounting emphasis in the literature on the adaptive capacity of health care institutions and systems, recent studies have suggested that the individual adaptive capacity of workers at the forefront of health care delivery shows increasing importance to organisational effectiveness in coping with contingencies and changed situations in large‐scale health care emergencies (Rumsey et al. 2014). The findings of this study offer needed insight into strategies to empower the adaptive capacity of frontline emergency nurses in response to public health events. To promote the development of adaptive capacity, strategies to develop and transfer tacit knowledge among emergency nurses should be taken into consideration in formulating measures to enhance their preparedness for imminent EID outbreaks and other large‐scale public health emergencies.

Relevance to clinical practice

The development of strategies to bridge guideline‐practice gaps is a critical need identified by this study. As suggested by the findings, customisation of the recommendations and guidelines to the immediate needs of the frontline personnel is important. This study casts light on the need to involve experienced frontline nurses who are specialised in the field of emergency nursing as representatives in policy and guideline planning. Their involvement in the planning process could provide practical information to allow policymakers to better tailor the protocols and ensure that they are compatible with current practices (Batcheller et al. 2004). Also, the participation of frontline leaders could also improve the efficiency of guidelines by means of appropriate modifications to address the actual needs of frontline personnel in clinical situations (Matthew‐Maich et al. 2013).

In addition to practicality, the maintenance of cross‐departmental consensus among health care personnel on guideline interpretation and operation was also indicated as an important component for efficient implementation. It is therefore necessary for health care service administrators to ensure that guidelines are disseminated effectively to staff in conjunction with relevant reference materials. The findings in this study highlight the need to strengthen cross‐departmental communication so as to ensure coherent understanding of terms and instructions and the consistent implementation of guidelines. Other studies have indicated that the dissemination of information over the course of infectious disease outbreaks could be chaotic because information provided by the administrators was excessive and inconsistent (Lam & Hung 2013). Thus, health care administrators should not only merely disseminate information among personnel across services but also appropriately streamline the guidelines and instructions to facilitate their integration into routine practice.

Because the findings suggest that routine nursing practices might be susceptible to negative effects from the introduction of new guidelines, it may be worthwhile to regularly monitor the relevance and effect of the guidelines. Regular monitoring is critical for policymakers to track the progress of guideline implementation and to assess whether the intended positive outcomes have been achieved (Grol et al. 2013). A clinical audit, as incorporated in a number of health care systems, might serve the purpose of quality monitoring. This method has been proposed as an efficient and effective means to assess the quality of practice and promote quality improvement (Pedersen et al. 2014). However, health care professionals might be unwilling to participate in auditing because they perceive the process as criticising and faultfinding (Bowie et al. 2012). To ensure smooth audits, their purposes and procedures should be clearly articulated to frontline personnel to avoid misconceptions.

In addition to implications for practice, this study demonstrates important implications for research. In future investigations, it would seem fruitful to explore possible difficulties in guideline implementation in other clinical settings, such as isolation wards and intensive care units, considering that enormous changes in regulations and recommendations are anticipated in these units in response to impending EID events. In addition, large‐scale infectious disease outbreaks commonly lead to numerous negative consequences to the health care system, personnel and resources in an intertwined manner. The guideline‐practice gaps identified in this study apparently offer only a partial account of the challenges in the management of EIDs. Further studies with greater focus on the comprehensive duties of frontline emergency nurses in managing EIDs are therefore suggested.

Limitations

Although this study offers significant insight into the guideline‐practice gaps in emergency care settings, its limitations should be considered. The sample size was relatively small, which may have influenced the extensive exploration of the experience of emergency nurses in guideline implementation. Still, because in‐depth interviews were adopted, detailed data and deep insights were gathered from the participants' narratives, which may counter some of the limitations of the small sample size (Denzin 1989, Silverman 1993). Another limitation involves the timing of the investigation. Because the focus of this study was issues‐related to guideline implementation in response to EIDs, the ideal data collection time would be in the midst of an outbreak. Since there had been no recent outbreaks of disease, data collection was scheduled right after the announcement of the emergence of a new strain of avian flu (H7N9) in December 2013. Nevertheless, it is believed that this study will contribute to a fuller understanding of the guideline‐practice gap encountered by emergency nurses in meeting the challenges from EIDs.

Conclusions

With the current emphasis on the competent management of infectious disease outbreaks, it is critical to understand the existing situations regarding guideline implementation in the management of EIDs. The emergency nurses' descriptions of their experiences have uncovered the difficulties in transferring the suggested guidelines into practice in emergency care settings and the nurses' corresponding strategies to address the problems. Strategies that take into consideration these issues might have great potential to promote successful guideline implementation in an emergency nursing context.

Contributions

Study design: SKKL, EWYK, MSYH, SMCP; Data collection and analysis: SKKL, MSYH, SMCP; Manuscript preparation: SKKL, EWYH, MSYH, SMCP.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Barriball KL & While A (1994) Collecting data using a semi‐structured interview: a discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing 19, 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batcheller J, Burkman K, Armstrong D, Chappell C & Carelock JL (2004) A practice model for patient safety: the value of the experienced registered nurse. Journal of Nursing Administration 34, 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blachere FM, Lindsley WG, Pearce TA, Anderson SE, Fisher M, Khakoo R & Beezhold DH (2009) Measurement of airborne influenza virus in a hospital emergency department. Clinical Infectious Diseases 48, 438–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie P, Bradley NA & Rushmer R (2012) Clinical audit and quality improvement – time for a rethink? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 18, 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs C (2000) Interview. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 9, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Carter EJ, Pouch SM & Larson EL (2014) Common infection control practices in the emergency department: a literature review. American Journal of Infection Control 42, 957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenitz WC & Swanson JM (1986) Qualitative research using grounded theory In From Practice to Grounded Theory (Chenitz WC. & Swanson JM. eds). Addison‐Wesley, Menlo Park, CA, pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chertow DS, Kleine C, Edwards JK, Scaini R, Giuliani R & Sprecher A (2014) Ebola virus disease in West Africa – clinical manifestations and management. New England Journal of Medicine 371, 2054–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SPP, Pang SMC, Cheung K & Wong TKS (2011) Stabilizing and destabilizing forces in the nursing work environment: a qualitative study on turnover intention. International Journal of Nursing Studies 48, 1290–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling BJ, Park M, Fang VJ, Wu P, Leung GM & Wu JT (2015) Preliminary epidemiologic assessment of MERS‐CoV outbreak in South Korea, May–June 2015. Euro Surveillance: Bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European Communicable Disease Bulletin 20, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2012) Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK (1989) The Research Act, 3rd edn Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Dey I (1993) Qualitative Data Analysis: A User‐Friendly Guide for Social Scientists. Routledge, London. [Google Scholar]

- Efstathiou G, Papastavrou E, Raftopoulos V & Merkouris A (2011) Factors influencing nurses' compliance with standard precautions in order to avoid occupational exposure to microorganisms: a focus group study. BioMed Central Nursing 10, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S & Kyngäs H (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar JJ & Piot P (2014) The Ebola emergency – immediate action, ongoing strategy. New England Journal of Medicine 371, 1545–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham ID, Logan J, Davies B & Nimrod C (2004) Changing the use of electronic fetal monitoring and labor support: a case study of barriers and facilitators. Birth 31, 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M & Davis D (2013) Improving Patient Care: The Implementation of Change in Health Care. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester. [Google Scholar]

- Hick JL, Hanfling D, Burstein JL, DeAtley C, Barbisch D, Bogdan GM & Cantrill S (2004) Health care facility and community strategies for patient care surge capacity. Annals of Emergency Medicine 44, 253–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothari A, Rudman D, Dobbins M, Rouse M, Sibbald S & Edwards N (2012) The use of tacit and explicit knowledge in public health: a qualitative study. Implementation Science 7, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam KK & Hung SYM (2013) Perceptions of emergency nurses during the human swine influenza outbreak: a qualitative study. International Emergency Nursing 21, 240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppin A & Aro AR (2009) Risk perceptions related to SARS and avian influenza: theoretical foundations of current empirical research. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 16, 7–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel J, Bui‐Xuan EF, Carreau AM, Carrier JD, Larkin É, Vlachos‐Mayer H & Dumas ME (2013) Respiratory hygiene in emergency departments: compliance, beliefs, and perceptions. American Journal of Infection Control 41, 14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew‐Maich N, Ploeg J, Dobbins M & Jack S (2013) Supporting the uptake of nursing guidelines: what you really need to know to move nursing guidelines into practice. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing 10, 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May C, Sibley A & Hunt K (2014) The nursing work of hospital‐based clinical practice guideline implementation: an explanatory systematic review using Normalisation Process Theory. International Journal of Nursing Studies 51, 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meslin EM (2009) Achieving global justice in health through global research ethics: supplementing Macklin's ‘top‐down’ approach with one from the ‘ground up’ In Global Bioethics: Issues of Conscience for the Twenty‐First Century (Green RM, Donovan A. & Jauss SA. eds). University Press, New York, pp. 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Minichiello V, Aroni R, Timewell E & Alexander L (1990) In‐Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire Pty Limited, Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg H (2012) Managing the myths of health care. World Hospitals and Health Services 48, 05. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse S (2012) Public health surveillance and infectious disease detection. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism 10, 6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol K, Bigelow P, O'Brien‐Pallas L, McGeer A, Manno M & Holness DL (2008) The individual, environmental, and organizational factors that influence nurses' use of facial protection to prevent occupational transmission of communicable respiratory illness in acute care hospitals. American Journal of Infection Control 36, 481–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan A, Domenighini F, Signorini L, Assini R, Catenazzi P, Lorenzotti S & Guerrini G (2008) Adherence to hand hygiene in an Italian long‐term care facility. American Journal of Infection Control 36, 495–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2015) Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen MS, Landheim A & Lien L (2014) Bridging the gap between current practice recommendations in national guidelines‐a qualitative study of mental health services. BioMed Central Health Services Research 14(Suppl 2), P94. [Google Scholar]

- Ploeg J, Davies B, Edwards N, Gifford W & Miller PE (2007) Factors influencing best‐practice guideline implementation: lessons learned from administrators, nursing staff, and project leaders. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing 4, 210–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretz JE & Folse VN (2011) Nursing experience and preference for intuition in decision making. Journal of Clinical Nursing 20, 2878–2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MHB & Boyle JS (1984) Ethnography: contributions to nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 9, 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson C (2002) Real Word Research. Blackwell, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Rose K (1994) Unstructured and semi‐structured interviewing. Nurse Researcher 1, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey M, Fletcher SM, Thiessen J, Gero A, Kuruppu N, Daly J & Willetts J (2014) A qualitative examination of the health workforce needs during climate change disaster response in Pacific Island Countries. Human Resources for Health 12, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M (2000) Focus on research methods‐whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health 23, 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier M (2012) Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Sage Publications, London. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman D (1993) Interpreting Qualitative Data‐Methods for Analyzing Talk, Text and Interaction. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Streubert HJ & Carpenter DR (1995) Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. Lippincott, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Sugerman D, Nadeau KH, Lafond K, Jhung M, Isakov A & Greenwald I (2011) A survey of emergency department 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) surge preparedness‐Atlanta, Georgia, July‐October 2009. Clinical Infectious Diseases 52(S1), 177–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DR (2006) A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Winpenny P & Glass J (2000) Interviewing in phenomenology and grounded theory: is there a difference? Journal of Advanced Nursing 31, 1485–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EL, Wong S, Lee N, Cheung A & Griffiths S (2012) Healthcare workers' duty concerns of working in the isolation ward during the novel H1N1 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Nursing 21, 1466–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2005) Combating Emerging Infectious Diseases in the South‐East Asia Region. Available at: http://www.searo.who.int/entity/emerging_diseases/documents/b0005.pdf (accessed 25 September 2013).

- Yagasaki K & Komatsu H (2011) Preconditions for successful guideline implementation: perceptions of oncology nurses. BioMed Central Nursing 10, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]