Abstract

Aim: This study has two objectives: to study the clinical symptoms associated with the detection of the four human coronaviruses (HCoVs), 229E, OC43, NL63 and HKU1 types, in the respiratory specimens sampled from hospitalised children in France between September 2004 and May 2005; and to develop a multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) assay allowing for the simultaneous detection of the four HCoVs.

Methods: 1002 respiratory specimens were tested for HCoVs. The clinical and epidemiological data were compared on the basis of the type HCoV infection.

Results: A hundred coronaviruses, 33 NL63, 2229E, 27 OC43 and 38 HKU1, were detected in 97 (9.8%) of 1002 samples negative in routine tests. The clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the study children were compared in three groups, 24 OC43‐, 27 NL63‐ and 34 HKU1‐infected children. HCoVs were identified mainly in children with upper and lower respiratory tract infections (50.5% vs. 29.4%). The significant difference in clinical presentation between the three coronavirus groups was the very low association between lower respiratory tract illness and HKU1 detection.

Conclusions: HCoV detection in hospitalised children without any other respiratory virus detection was associated with upper and a significant rate of lower respiratory tract illness. The four types of HCoVs were detected, and new types NL63 and HKU1 represented a substantial portion of detection. The multiplex RT‐PCR enabled a sensitive one‐time detection and the characterisation of all of the known HCoV types with the exception severe acute respiratory syndrome‐coronavirus.

Keywords: coronavirus, epidemiology, hospitalised children, multiplex RT‐PCR, respiratory tract infection

Coronaviruses are enveloped viruses with a single‐strand RNA genome and are divided into three groups named 1, 2 and 3. Five types of human coronaviruses (HCoVs) have been described: HCoVs 229E and OC43 were first identified in the mid‐1960s, and HCoVs NL63 and HKU1 were identified recently, in 2004 and 2005. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 HCoVs 229E and NL63 belong to group 1, while HCoVs OC43 and HKU1 belong to group 2. The last human coronavirus is severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)‐CoV which was identified during the SARS epidemic in 2003. 6 This epidemic was controlled and the SARS‐CoV is no longer circulating among humans. As a result, there are only four HCoVs with global circulation in the human population at this time. HCoVs 229E and OC43 are known as viruses causing upper respiratory tract illnesses and can elicit a more serious respiratory disease in children, the elderly and people with underlying disease. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 In several studies recently published, new coronaviruses NL63 and HKU1 have been found associated with a significant percentage of upper and lower respiratory tract infections. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Because of the difficulty designing studies with an appropriate control group, this association remains an important issue. This study has two objectives: to study the clinical diseases associated with the detection of the four HCoVs in the respiratory specimens sampled from hospitalised children in France between September 2004 and May 2005; and to develop and to validate a multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) assay allowing for the simultaneous detection of the four HCoVs.

Key Points

-

1

All four of the known non‐severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) type human coronaviruses (HCoVs) were detected in 5.7% of respiratory specimens sampled from hospitalised children. The four HCoVs were detected throughout the year, with a peak of circulation in winter–spring months in temperate climate regions.

-

2

The clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the study children were compared in three groups: 24 OC43‐, 27 NL63‐ and 34 HKU1‐infected children. HCoVs were identified mainly in children with upper and lower respiratory tract infections (50.5% vs. 29.4%). The significant difference in clinical presentation between the three coronavirus groups was the very low association between lower respiratory tract illness and HKU1 detection.

-

3

Our study shows that nearly one‐third of children admitted in hospital for respiratory tract illness suffered from underlying chronic conditions and proved considerable risk of complications. HCoVs may also be responsible for respiratory nosocomial infections.

-

4

It is therefore critical that HCoVs be screened more routinely in respiratory specimens in hospitals and that reliable viral detection methods be used. The multiplex reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction developed in this study enabled a sensitive one‐time detection and the characterisation of all of the known HCoV types with the exception SARS‐CoV.

Materials and Methods

Specimens

From September 2004 to May 2005, 1750 paediatric nasal aspirates were submitted to the laboratory for viral detection. These specimens were sampled from children admitted to the University Hospital of Caen and to the General Hospital of Flers for respiratory or general symptoms. The parents, or legal guardians of the patients, consented to having their samples tested for respiratory viruses. Routine tests allowing for the detection of influenza A, B and C viruses, respiratory syncytial viruses A and B (RSV), human metapneumoviruses, para‐influenza viruses 1, 2 and 3, adenovirus, enterovirus and rhinovirus were performed using immunofluorescence assays, culture isolation and molecular methods previously described. 20 , 21 Seven hundred 48 specimens (42.7%) were found positive. Out of the total number of the sample cohort, the RSV‐positive specimens represented 14.9%; the rhinovirus‐positive 13%; the influenza A and B viruses‐positive 6.7%; the parainfluenza viruses‐positive 4.2%; the human metapneumoviruses‐positive 3%; the adenovirus‐positive 2.5%; and the enterovirus‐positive 2.3%. The 1002 remaining specimens were tested for human coronaviruses. They were sampled from 928 patients aged from 0 to 16 years with a sex ratio of 1.27 (520 boys vs. 408 girls). The age distribution of the sampled population was as follows: 275 patients <6 months of age (29.2%), 267 patients 6–24 months of age (28.8%), 233 patients 2–6 years of age (25.1%), and 153 patients 6–16 years of age (16.5%). In total, 58.4% of the sampled population was younger than 2 years old. The monthly distribution of the sampling showed that more than 70% of nasal aspirates were sampled between December 2004 and April 2005.

Molecular methods

A multiplex one‐step RT‐PCR assay was developed to detect HCoVs 229E, OC43, NL63 and HKU1 simultaneously. RNA was extracted by using the High Pure RNA isolation kit (Roche, Germany). Then, a one‐step RT‐PCR amplification of different size products –255 bp for NL63 type, 334 bp for OC43 type, 443 bp for HKU1 type and 579 bp for 229E type – was performed using primers previously described in N and M genes. 14 , 22 , 23 Three HKU1 genotypes A, B and C were recently described in 2006 by Woo et al. 24 In order to allow for the amplification of these three HKU1 genotypes, our original HKU1 primers designed from the genotype A strain referenced AY597011 in GenBank, were degenerated as follows: HKU1 sensmod (5′‐ATCTGARCGAAAYYAYCAAAC‐3′) and HKU1 antisensemod (5′‐CGYAAACCTAGTAGGGATAGCTT‐3′). The RT‐PCR was undertaken using one‐step RT‐PCR kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) according to the manufacturer's protocol. In each serial manipulation, negative and positive controls were included. The comparative analytical sensitivities of the four single RT‐PCR assays and the one multiplex RT‐PCR assay were studied by analysing serial 10‐fold dilutions of positive controls and were found equivalent with respect to their intended targets. A potential cross‐reactivity among HCoV primers was eliminated by analysing the 15 different combinations of positive controls. RT‐PCR products were processed on an agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualised under UV light. Only the samples with a positive detection of an amplified product were subjected to a hybridisation test (GEN‐ETI‐K DEIA, Sorin, Italy) confirming the specificity of such an amplified product. The probes used were previously described for HCoVs 229E, OC43 and NL63. 14 , 22 , 23 The sequence HKU1 probe was degenerated for detecting the three genotypes as follows: 5′‐Biotin CCCATTGCTTWCGGRATACCCCCTT‐3′.

Patient evaluation

For all patients with HCoV‐positive detection, a retrospective examination of the medical record was conducted by an independent physician using standardised written form. The questions included personal information, medical history, all detailed signs and symptoms of the acute disease, required laboratory and radiological examinations, number of days between the beginning of illness and a positive coronavirus sample and clinical outcome (duration of hospitalisation, transfer to intensive care unit). The number of days between admission and a positive coronavirus sample taken, along with the duration of symptoms, was taken into consideration for determining nosocomial infection. After a complete examination, the medical records were classified on the basis of a final diagnosis: upper respiratory tract illness, lower respiratory tract illness without wheezing, bronchiolitis, exacerbation of asthma, gastro‐enteritis. The data were analysed using the χ2 exact test for qualitative data, and Krushal–Wallis's test for quantitative data, and then compared on the basis of the type of HCoV infection. Cases of co‐detection of two coronaviruses were not analysed.

Results

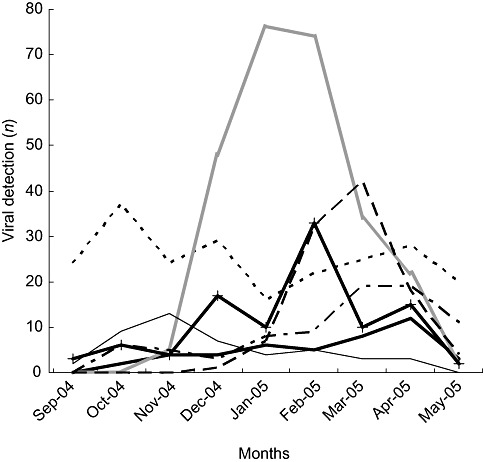

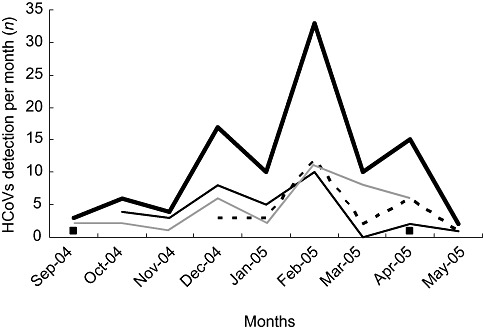

A hundred coronaviruses were detected in 97 (9.8%) of 1002 samples negative in routine tests, accounting for 5.7% of total samples of the cohort. HCoVs were the fourth most frequent circulating viruses in this study, after RSV, rhinoviruses and influenza A and B viruses (Fig. 1). The process of testing only the routine test negative samples underestimated the prevalence of coronaviruses and excluded the detection of two or more different viruses. However, this process allowed us to associate the described clinical symptoms with HCoV infection only. Three samples were positive for two coronaviruses (two cases due to OC43 and HKU1, and one case due to 229E and NL63). Coronaviruses were detected in every month of the study. However, HCoV infection mainly occurred in the winter and spring months, with a peak in February (Fig. 2). Out of the 100 coronaviruses detected, 35 belonged to group 1 (33 NL63 and 2229E), while 65 belonged to group 2 (27 OC43 and 38 HKU1). Sixty‐three per cent of the HCoV‐infected patients were younger than 2 years old. The age distribution of HCoV‐infected patients was equivalent to the age distribution of sampled patients. The 97 HCoV‐positive samples were taken from 90 patients. Only the 87 mono‐coronavirus infected children were included in clinical analysis. In the end, clinical data were available for 86 children with one lost case. With only one case of mono‐detection of HCoV‐229E, we chose not to include the 229E infection group in the comparative study. The clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the study children were thus compared in three groups, 24 OC43‐, 27 NL63‐ and 34 HKU1‐infected children, and were summarised in Table 1. The age and weight of the children were similar in the three groups. The sex ratio was higher in the HKU1 group (2.1 vs. 0.85 and 0.59), the difference barely significant. Thirty‐three per cent of HCoV‐infected children suffered from at least one underlying chronic condition. The delay between the beginning of the illness and admission to the hospital was from 3.2 to 6.3 days and the median duration of hospitalisation was equivalent for the three groups (from 2.8 to 4.9 days). We found evidence of nosocomial acquisition of coronavirus in two cases. The first one was an OC43‐infected female child. She was 1 month old and was hospitalised in the neonatology department for prematurity. The nasal aspirate sampled 30 days after her admission was OC43 positive thought she had not left the hospital. The second case was a 9‐month‐old male child suffering from oesophageal atresia and admitted for parenteral nutrition. He was hospitalised for 75 days and contracted pneumonia at day 18. Five nasal aspirates were sampled on D17, D18, D23, D32 and D42. The first three were positive for NL63 detection, the fourth was positive for 229E detection, and the last was positive for RSV detection. HCoVs were identified mainly in children with respiratory tract infections while upper respiratory tract infections were more common than lower respiratory tract infections (50.5% vs. 29.4%). The significant difference in clinical presentation between the three coronavirus groups was the very low association between lower respiratory tract illness and HKU1 detection. Of the 34 HKU1‐positive children, none suffered from bronchiolitis, and 11 (32.4%) were without respiratory symptoms at the sampling time and within the 24 following hours. A significant number of patients (from 25.9% to 38.2%) had a gastrointestinal infection associated, in 56% of the cases, with rotavirus or adenovirus detection in stools (data not shown). Of the 34 HKU1‐infected children, six (17.6%) were admitted for epilectic seizures, three suffering from underlying neurological disease (familial epilepsy with susceptibility gene, agenesis of corpus callosum, neonatal epilepsy after temporal lobe haemorrhage). In this study, HKU1 detection was not associated with a high frequency of febrile seizures. Likewise, NL63 detection was not found to be associated with a high frequency of croup. No statistical differences were observed for laboratory or radiological characteristics between subtype HCoVs. Finally, oxygenotherapy was required for eight children. Three children out of 85 required intensive care. No death was reported.

Figure 1.

Number of respiratory virus‐positive specimens detected each month of the study. In the month of February, coronavirus detection is as often frequent as that of influenza viruses. ( ) Adenovirus; (‐ ‐ ‐ ‐) rhinovirus; (

) Adenovirus; (‐ ‐ ‐ ‐) rhinovirus; ( ) respiratory syncytial viruses; (– –) influenza; (– ‐ –) para‐influenza; (

) respiratory syncytial viruses; (– –) influenza; (– ‐ –) para‐influenza; ( ) enterovirus; (

) enterovirus; ( ) coronavirus.

) coronavirus.

Figure 2.

Number of HCoV‐positive respiratory specimens detected each month of the study. ( ) Total HCoVs; (

) Total HCoVs; ( ) 229E; (‐ ‐ ‐) OC43; (

) 229E; (‐ ‐ ‐) OC43; ( ) NL63; (

) NL63; ( ) HKU1. HCoV, human coronavirus.

) HKU1. HCoV, human coronavirus.

Table 1.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the HCoV‐infected study children

| Characteristics | OC43 group (n = 24) | NL63 group (n = 27) | HKU1 group (n = 34) | P‐vaule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex ratio M/F | 0.85 | 0.59 | 2.1 | 0.058 |

| Average age (years) | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.7 | ns |

| Weight (kg) | 12.4 | 13.1 | 12.2 | ns |

| Underlying chronic condition† | 11 (43.8%) | 9 (33.3%) | 8 (23.5%) | ns |

| Average temperature‡ | 38°C (36.7–40.2) | 38.2°C (36.5–40.1) | 37.9°C (36.3–40.3) | ns |

| Fever (>37.5°C) | 12 (50%) | 14 (52%) | 15 (44%) | ns |

| O2 | 3 (12.5%) | 3 (11.1%) | 2 (2.9%) | ns |

| Intensive care unit transfert | 0 | 1 | 2 | ns |

| Duration of hospitalisation (days) | 4.9 | 2.8 | 3.9 | ns |

| Delays in days§ | 6.3 | 3.4 | 3.2 | ns |

| Upper respiratory tract illness | 13 (54.2%) | 12 (44.4%) | 18 (52.9%) | ns |

| Rhinopharyngitis | 4 (16.6%) | 3 (11.1%) | 4 (11.8%) | ns |

| Laryngitis | 1 (4.2%) | 3 (11.1%) | 0 | ns |

| Conjunctivitis | 4 (16.6%) | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | ns |

| Otitis | 4 (16.6%) | 8 (29.6%) | 5 (14.7%) | ns |

| Lower respiratory tract illness | 8 (33.3%) | 12 (44.4%) | 5 (14.7%) | <0.035 |

| Bronchiolitis | 4 (16.6%) | 7 (25.9%) | 0 | <0.010 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (12.5%) | 3 (11.1%) | 2 (5.9%) | ns |

| Exacerbation of asthma | 1 (4.2%) | 2 (7.4%) | 3 (8.8%) | ns |

| Gastroenteritis | 8 (33.3%) | 7 (25.9%) | 13 (38.2%) | ns |

| Rotavirus or adenovirus in stools | 5/8 | 3/7 | 8/13 | |

| Epilectic seizures | 0 | 2 (7.4%) | 6 (17.6%) | ns |

| No respiratory sign¶ | 3 (12.5%) | 3 (11.1%) | 11 (32.4%) | 0.066 |

Comparative analysis was based on the type OC43 (n = 24), NL63 (n = 27) or HKU1 (n = 34) of coronavirus detected in respiratory specimens. The 229E group was not included in the comparative analysis because of the low rate of detection of this type in this study. †Underlying chronic conditions: cardiac or neurological malformations, de DiGeorges syndrom, acute leukemia, Dandy–Walker syndrom, Williams and Beuren syndrom, prematurity, Elhers Danlos illness, asthma, bronchodysplasia, mucoviscidose, Stickler syndrom, oesophageal atresia. ‡Temperature at sampling time or within the 24 following hours. §Delay between the beginning of illness and admission to hospital. ¶No respiratory symptom at the sampling time and the 24 following hours. ns, not significant.

Discussion

All four of the known non‐SARS type human coronaviruses were detected in 5.7% of respiratory specimens sampled from hospitalised children in France during autumn, winter and spring 2004–2005. This rate is consistent with those recently published in 2006 and 2007 by authors studying the circulation of the HCoVs in different populations, during different periods of year, and using different molecular methods: Lau et al., 18 Hong Kong, 2.1%; Gerna et al., 16 Italy, 6.4%; Esposito et al., 25 Italy, 3.8%; Garbino et al., 26 Switzerland, 5.4%; and Kuypers et al., 19 USA, 6.3%. Consistence is also found in these studies, to include our own, with respect to the detection of the four HCoVs throughout the year, with a peak of circulation in winter–spring months in temperate climate regions. In our study, group 2 HCoVs (types OC43 and HKU1, 65%) were more prevalent than group 1 HCoVs (types NL63 and 229E, 35%). This type repartition was not found in all studies, showing that the epidemiological data on HCoV epidemics must be reviewed. 12 , 25 More specifically, our understanding of overlapping epidemics, or possible variation from year to year, in the relative incidence of the different types, must be improved. Further continuous studies conducted over several years are necessary. However, significant progress can only be made in the study of human coronavirus infections upon the development of reliable, currently available and relatively inexpensive methods for detecting the different subtypes of HCoVs. The increasing number of type HCoVs, the description of new recombinant variants and the genetic variability of these viruses create obstacles in the development of updated molecular and immunological assays. Efficient strategies in molecular methodology depend upon adequate knowledge of limitations in techniques. Consensus methods, often using degenerated primers defined in conserved gene, theoretically allowed for the detection of all types, as well as the potential detection of new variants. However, some authors found that consensus assays were less sensitive than methods using type‐specific primers. 15 , 16 The multiplex PCR provides an interesting alternative approach tested in this study. Nonetheless, our approach involved the development of classical PCR, using, first of all, the detection of amplified products and, then, an hybridisation assay. The next challenge will be the development of a sensitive and inexpensive multiplex real‐time PCR. It must also be kept in mind that the development and validation of monoclonal antibodies has been critical in rapid and easily available diagnosis of respiratory viral infections.

Detection of a coronavirus in respiratory specimens negative for viral routine tests was associated with upper and lower respiratory tract diseases in hospitalised children in 50.5% and 29.4% of cases, respectively. Around 10% of the patients (eight out of 85) required oxygenotherapy. The pathologic impact of HCoV infection varied according to the design of study population. Esposito et al. recently suggested in a prospective study conducted in Italy, that the different types of HCoVs have a limited clinical impact on otherwise healthy children who checked into an emergency ward. In this study, patients with underlying chronic diseases were excluded and HCoVs were mainly associated with upper respiratory tract illness (72%). 25 In a study, also conducted in Italy, by Gerna et al. and included 823 patients from whom one‐third were immunocompromised, HCoVs were detected in 74.5% of cases with lower respiratory tract illness and in 25.5% of those with upper respiratory tract illness. 16 Although HCoVs may be considered as low pathogenic viruses responsible for limited diseases in the wider population and treated by general practitioners, our study shows that nearly one‐third of children admitted in hospital for respiratory tract illness suffered from underlying chronic conditions and proved considerable risk of complications. HCoVs may also be responsible for respiratory nosocomial infections. It is therefore critical that HCoVs be screened more routinely in respiratory specimens in hospitals and that reliable viral detection methods be used. The comparative analysis of clinical symptoms associated with the detection of different HCoV types suggested that the type HKU1, the most frequently detected in our study, was less often associated with lower respiratory diseases than the other types and could be detected in a larger range of diseases. These data were consistent with recently reported findings of no association between bronchiolitis and pneumonia in hospitalised children and HKU1 detection. 12 The specific pathologic pattern of HCoV type remains to be more thoroughly investigated. We previously showed that HCoV‐HKU1, like SARS‐CoV, and probably the other types, can be excreted in stools. 23 Unfortunately, stools sampled from enrolled children were not available and could not be tested for HCoVs. The shedding of HCoVs in gastrointestinal tissues probably plays an determining role in viral transmission and could be responsible for diseases in some patients. HCoVs 229E and OC43 are also suspected of playing a role in neurological diseases, and HKU1 may play a role in epilectic seizures. 18 Such an association was not found in this study. Nevertheless, the potential neurotropism of HKU1 and HCoV strains in general merits more investigations.

Conclusion

In sum, HCoV detection in people without any other respiratory virus detection was associated with upper respiratory tract illness and a significant rate of lower respiratory tract illness in hospitalised children. One‐third of HCoV‐infected children suffered from underlying chronic diseases. The four types of HCoVs were detected, and new types NL63 and HKU1 represented a substantial portion of detection. The multiplex RT‐PCR developed in this study enabled a sensitive one‐time detection and the characterisation of all of the known HCoV types with the exception SARS‐CoV.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by The European Commission EPISARS contract (SP22‐CT‐2004‐511063) and the Programme de Recherche en Réseaux Franco‐Chinois (épidémie du SRAS: de l'émergence au contrôle).

References

- 1. McIntosh K, Dees JH, Becker WB, Kapikian AZ, Chanock RM. Recovery in tracheal organ cultures of novel viruses from patients with respiratory disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1967; 57: 933–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fouchier RA, Hartwig NG, Bestebroer TM et al. A previously undescribed coronavirus associated with respiratory disease in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004; 101: 6212–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamre D, Procknow JJ. A new virus isolated from the human respiratory tract. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1966; 121: 190–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Der Hoek L, Pyrc K, Jebbink MF et al. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat. Med. 2004; 10: 368–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Woo PC, Lau SK, Chu CM et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J. Virol. 2005; 79: 884–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003; 348: 1967–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nokso‐Koivisto J, Pitkäranta A, Blomqvist S, Kilpi T, Hovi T. Respiratory coronavirus infections in children younger than two years of age. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 2000; 19: 164–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vabret A, Mourez T, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Freymuth F. An outbreak of coronavirus OC43 respiratory infection in Normandy, France. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003; 36: 985–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McIntosh K, Chao RK, Krause HE, Wasil R, Mocega HE, Mufson MA. Coronavirus infection in acute lower respiratory tract disease of infants. J. Infect. Dis. 1974; 130: 502–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pene F, Merlat A, Vabret A et al. Coronavirus 229E‐related pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003; 37: 929–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Falsey AR, McCann RM, Hall WJ. The ‘common cold’ in frail older persons: impact of rhinovirus and coronavirus in a senior daycare center. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1997; 45: 706–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gerna G, Percivalle E, Sarasini A et al. Human respiratory coronavirus HKU1 versus other coronavirus infections in Italian hospitalised patients. J. Clin. Virol. 2007; 38: 244–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bastien N, Robinson JL, Tse A, Lee BE, Hart L, Li Y. Human coronavirusNL‐63 infections in children: a 1‐year study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005; 43: 4567–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vabret A, Mourez T, Dina J et al. Human coronavirus NL63, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005; 11: 1225–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiu SS, Chan KH, Chu KW et al. Human coronavirus NL63 infection and other coronavirus infections in children hospitalized with acute respiratory disease in Hong Kong, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005; 40: 1721–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gerna G, Campanini G, Rovida F et al. Genetic variability of human coronavirus OC43‐, 229E‐, and NL63‐like strains and their association with lower respiratory tract infections of hospitalized infants and immunocompromised patients. J. Med. Virol. 2006; 78: 938–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van der Hoek L, Sure K, Thorst G et al. Croup is associated with the novel coronavirus NL63. PLoS Med. 2005; 2: e240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lau SK, Woo PC, Yip CC et al. Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006; 44: 2063–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuypers J, Martin ET, Heugel J et al. Clinical disease in children associated with newly described coronavirus subtypes. Pediatrics 2007; 119: e70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bellau‐Pujol S, Vabret A, Legrand L et al. Development of three multiplex RT‐PCR assays for the detection of 12 respiratory RNA viruses. J. Virol. Methods 2005; 126: 53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Freymuth F, Vabret A, Cuvillon‐Nimal D et al. Comparison of multiplex PCR assays and conventional techniques for the diagnostic of respiratory virus infections in children admitted to hospital with an acute respiratory illness. J. Med. Virol. 2006; 78: 1498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vabret A, Mouthon F, Mourez T, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Freymuth F. Direct diagnosis of human respiratory 229E and OC43 by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Virol. Methods 2001; 97: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vabret A, Dina J, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Corbet S. Freymuth. Detection of the new human coronavirus HKU1: a report of 6 cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006; 42: 634–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woo PC, Lau SK, Yip CC et al. Comparative analysis of 22 coronavirus HKU1 genomes reveals a novel genotype and evidence of natural recombination in coronavirus HKU1. J. Virol. 2006; 80: 7136–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Esposito S, Bosis S, Niesters HG et al. Impact of human coronavirus infections in otherwise healthy children who attended an emergency department. J. Med. Virol. 2006; 78: 1609–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garbino J, Crespo S, Aubert JD et al. A prospective hospital‐based study of the clinical impact of non‐severe acute respiratory syndrome (Non‐SARS)‐related human coronavirus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006; 43: 1009–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]