Abstract

Purpose

To compare T1 values of blood and myocardium at 1.5T and 3T before and after administration of Gd‐DTPA‐BMA in normal volunteers, and to evaluate the distribution of contrast media between myocardium and blood during steady state.

Materials and Methods

Ten normal subjects were imaged with either 0.1 mmol/kg (N = 5) or 0.2 mmol/kg (N = 5) of Gd‐DTPA‐BMA contrast agent at 1.5T and 3T. T1 measurements of blood and myocardium were performed prior to contrast injection and every five minutes for 35 minutes following contrast injection at both field strengths. Measurements of biodistribution were calculated from the ratio of ΔR1 (ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood).

Results

Precontrast blood T1 values (mean ± SD, N = 10) did not significantly differ between 1.5T and 3T (1.58 ± .13 sec, and 1.66 ± .06 sec, respectively; P > 0.05), but myocardium T1 values were significantly different (1.07 ± .03 sec and 1.22 ± .07 sec, respectively; P < 0.05). The field‐dependent difference in myocardium T1 postinjection (T1@3T – T1@1.5T) decreased by approximately 72% relative to precontrast T1 values, while the field‐dependent difference of blood T1 decreased only 30% postcontrast. Measurements of ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood were constant for 35 minutes postcontrast, but changed between 1.5T and 3T (0.46 ± .06 vs. 0.54 ± .06, P < 0.10).

Conclusion

T1 is significantly longer for myocardium (but not blood) at 3T compared to 1.5T. The differences in T1 due to field strength are reduced following contrast administration, which may be attributed to changes in ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood with field strength. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2006. © 2006 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: contrast agent, 3T, myocardium, T1 measurement, image contrast

CURRENTLY THERE IS significant interest in using cardiac MRI at field strengths greater than 1.5T (1, 2, 3, 4). This includes a number of applications that use contrast agents for cardiac studies, such as delayed enhancement imaging, first‐pass myocardial perfusion, and MR angiography (MRA). The pharmacokinetics of gadolinium‐based contrast agents (e.g., Gd‐DTPA‐BMA) have been well described in both animals and humans (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10), and it has been shown that determining the regional contrast agent concentration is an important predictor for signal enhancement in pathologic regions (9, 11). However, signal enhancement depends not only on pharmacokinetics and imaging parameters, but also on magnetic field strength (B0), which causes the spin‐lattice relaxation times (T1) in most biological tissues to change (2, 12, 13, 14). However, the magnitude (and variation among individuals) of T1 differences between 1.5T and 3T for blood and myocardium pre‐ and postcontrast are unknown.

One of the indirect consequences of circulating contrast media is that the modulation in T1 is not constant over time and among all patients. As a result, it is challenging to obtain consistent image contrast post‐injection. An impression of the change in T1 over time post‐injection can be realized by studying the contrast kinetics of blood and myocardium in healthy human volunteers. From the time course of T1 change, conclusions can be made about the role of the paramagnetic agent in each of these tissue compartments (blood and myocardium). By extending the study to 3T, one can both compare relaxation times between fields and assess the dependency of the contrast media on the field strength and tissue compartment. Postcontrast T1 values in blood and myocardium are necessary to optimize pulse sequences at different field strengths.

The measurement of postcontrast T1 values also enables evaluation of the partition coefficient (λmyo), which has significance in describing the pathologic state of injured myocardium (5, 15, 16). Since the partition coefficient is an inherent physiological property, its value should not depend on MR properties, such as field strength. Although measurements of λmyo have been performed at 1.5T (16), they have not been evaluated at 3T in the same subset of people. It is important to evaluate partition coefficient values if perfusion and biodistribution studies are to be extended to high field strengths.

Relaxation rates (R1 = 1/T1) are often used to describe the effect of contrast media on tissue relaxation. Many mechanisms contribute to the relaxation rate, and these mechanisms can be linearly combined to express an “observed” R1 value (R 1obs). As such, the contribution from contrast media can be isolated from the precontrast R1 (R 1pre) to express meaningful information about tissue enhancement (17) and regional distribution of the contrast agent (18) from the following expression (15, 18):

| (1) |

where fECV is the extracellular volume fraction, r 1 is the longitudinal relaxivity of the contrast agent (19), and [CA] and [CA]EC are the contrast agent concentration in tissue and extracellular compartment, respectively. Note that R1contrast is equivalent to the change in R1 over time (ΔR 1(t)), i.e., R1contrast ≡ ΔR 1(t) = R1obs − R1pre. The primary term in R 1contrast that may be subject to field dependency is r 1, since [CA] and fECV are constant for a given dose and individual, respectively. Although it has been shown that r 1 is less sensitive to field changes above 1.5T (20), other reports suggest a tissue‐specific change in r 1 (9, 19, 21, 22). Additional data are needed to determine whether contrast media affects relaxation uniquely at different field strengths.

An informative index of the distribution behavior of Gd‐DTPA‐BMA in myocardium and blood can be assessed with MRI by considering the ratio of ΔR 1(t) between myocardium and blood:

| (2) |

This expression has been used to determine the tissue distribution volume and assess the cellular integrity in ischemic and necrotic myocardium (5, 15, 16), under the assumption that there is fast exchange and a steady‐state concentration between extracellular compartments ([CA]EC‐myo = [CA]EC‐plasma). The factor fECV/(1.0 − Hct) relates the extracellular volume of distribution between myocardium and blood, and is equivalent to the partition coefficient (λmyo). If the ratio of relaxivities (r1myo/r1blood) is unity, then λmyo = ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t), which should be the same between 1.5T and 3T. A measurable change in ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) between 1.5T and 3T may indicate a field‐dependent change in r1myo/r1blood.

The focus of this investigation was to measure T1 of blood and myocardium in human subjects at two imaging field strengths (1.5T and 3T) before and after contrast agent injection. T1 values were determined precontrast injection and at every five minutes postcontrast for 35 minutes. In addition, the distribution of contrast media between myocardium and blood at 1.5T and 3T was quantitatively investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

T1 Measurement Sequences

All experiments were performed using commercially available Gd‐DTPA‐BMA (Omniscan, Amersham, Oslo, Norway) from 20‐mL prefilled syringes. Precontrast T1 values of blood and myocardium were calculated from a set of four ECG‐gated, inversion recovery (IR), single‐shot, balanced steady‐state free precession (b‐SSFP) sequences (FOV = 300 × 285 mm, 90 lines acquired (using 80% scan percentage) reconstructed to 256 matrix, thickness = 8 mm, TR/TE/α = 2.5 msec/1.2 msec/35°, readout duration = 225 msec). This sequence is similar to one presented previously (23), and hereafter is referred to as IRss. Magnetization preparation was performed with a nonselective adiabatic inversion pulse. Single‐shot imaging as a T1 measurement technique was used before contrast injection to eliminate the long repetition (and breath‐hold) times necessary to calculate longer blood and myocardial T1s at 3T. The inversion times (TIs) were slightly different at both field strengths to ensure points on either side of the zero‐crossing (1.5T: 400, 600, 1000, 1400 msec; 3T: 500, 800, 1100, 1500 msec). Because of the long TIs, a trigger delay was applied to provide imaging in diastole of the second heartbeat.

Postcontrast T1 values were calculated from two ECG‐gated, segmented IR b‐SSFP images (FOV = 300 × 285 mm, matrix = 256, 42 lines/segment, thickness = 8 mm, TR/TE/α = 3.1 msec/1.05 msec/40°, readout duration = 125 msec, three R‐R intervals, acquisition time = 12 heartbeats), with trigger delays set to ensure imaging of the same phase of the cardiac cycle (diastole). This sequence will be referred to as 2pt‐IR. The TI of the first image was set ≤ 150 msec, while the second TI was set maximally depending on the subject's heart rate (usually ≥ 650 msec). The temporal resolution for each postcontrast T1 measurement (two images) was less than one minute.

T1 Analysis

All signal values used for T1 fitting were normalized using the mean background noise to offset the differences in receiver gain and display scaling factors between the individual TI images. Precontrast T1 values (using IRss) were calculated from a two‐parameter fit assuming monoexponential relaxation and ideal spin inversion:

| (3) |

The fit enabled estimation of T1 and the scaling factor, F, from the measured (scaled) signal intensity, S, and TIs. The goodness of fit was determined from the r 2 value of the fit. Although it has been shown that the “observed” T1 (T1*) in IR b‐SSFP is less than the “true” T1 due to the transient approach to steady state (24), the acquisition duration (Tacq) of the current method is short (∼225 msec), which makes the magnetization decay rate during readout, E1* (E1* = exp(−Tacq/T1*)), negligible relative to “true” E1. As a result, the difference between the observed and true T1s is minor.

Postcontrast T1 was determined via a two‐point ratio method (using 2pt‐IR), as described elsewhere (25). Briefly, the two IR images (TI‐high and TI‐low) were identically scaled and divided (TI‐high/TI‐low). Since the imaging parameters were held constant (except for TI) and images scaled equivalently, the ratio of intensity values (intensity‐ratio) in each pixel was related to T1 by

| (4) |

where TIhigh and TIlow represent the TIs used in each image. Equation [4] was solved numerically for T1 using a modified Newton‐Rapshon method performed in Matlab 6.5 (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Note that the intensity‐ratio can have a positive or negative value, depending on the sign of the magnetization at the chosen TIs. Since only magnitude images were acquired in this analysis, the intensity‐ratio was always positive, which led to uncertainty about the true sign of the magnetization. This uncertainty resulted in two unique solutions in the 2pt‐IR analysis. However, by choosing a very low TI (TIlow ≤ 150 msec) coupled with a high TI, we assumed that the intensity‐ratio was always negative, even for the low blood T1's seen early after contrast injection (15, 16).

All images were taken offline for T1 calculation. In vivo T1 maps were generated from the postcontrast 2pt‐IR in Matlab by performing T1 calculations on a pixel‐by‐pixel basis. From the T1 maps, region‐of‐interest (ROI) measurements were taken from blood (one ROI: center of left ventricle) and myocardium (two ROIs: septum and posterior wall), and the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the measurement were recorded.

T1 Measurements in Phantoms

The T1 measurement techniques were validated in MR phantoms. Thirteen 50‐mL plastic vials containing distilled water were made with varying concentrations of Gd‐DTPA‐BMA contrast media (0 mM–2 mM Gd). The tubes were arranged in a head coil at 3T (Magnetom Trio; Siemens Medical Systems, Erlanger, Germany) and reference T1 relaxation times were measured using a segmented IR b‐SSFP sequence with 20 TI values spanning 90–6500 msec. The parameters for the sequence were FOV = 300 mm2, matrix = 256 × 256, TR/TE/α = 3.4 msec/1.26 msec/45°, 21 lines/segment, slice thickness = 8 mm, and segment interval = 7000 msec.

The IRss (used for precontrast T1 measurements) and 2pt‐IR (used for postcontrast T1 measurements) methods were used to measure T1 in the same 13 tubes, using TIs equivalent to those proposed for the in vivo experiments. A physiology simulator was used to supply a constant heart rate of 75 beats per minute (bpm). T1 maps were generated for both techniques, as described in the previous section, since sample motion was absent. The similarity with the reference T1 measurement technique was determined from the percent difference between the two values.

T1 Measurements In Vivo

Ten healthy human subjects (six males and four females, age = 29.7 ± 4.7 years) were recruited to participate in the study. The protocol in this study was approved by the university's institutional review board, and informed consent was provided by each volunteer. Each subject underwent two MRI studies: one at 1.5T (Philips Intera, Best, The Netherlands; five‐element phased‐array receive coil) and one at 3T (Siemens Magnetom Trio; eight‐element phased‐array receive coil). Both studies involved contrast administration of either 0.1 mmol/kg (N = 5, three males and two females) or 0.2 mmol/kg (N = 5, three males and two females) intravenously. The appropriate dose was determined according to each subject's weight. The subjects underwent each study at least 3 days apart and no more than 3 weeks apart, and 1.5T and 3T imaging studies were performed in random order.

Automatic shimming was performed at 1.5T, while at 3T local shim volumes were manually placed over the heart to reduce artifacts due to field inhomogeneities. T1 measurements were performed on a midventricular short‐axis slice. Following the precontrast T1 imaging protocols, contrast media was administered through a bolus injection in the antecubital vein, and subsequent postcontrast T1 measurements were made every five minutes for 35 minutes.

To characterize the effect of field dependence on relaxation times, the T1 difference between 1.5T and 3T was determined before and after contrast injection for blood and myocardium in each subject (T1@3T – T1@1.5T). This T1 difference was averaged over all subjects at a given dose, and represented a time course of T1 differences between 1.5T and 3T, before and after contrast injection.

Contrast Agent Distribution

The partition coefficient of a tissue can be approximated by measuring the ratio of ΔR 1 in each tissue compartment as outlined in Eq. [2]. ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) measurements were performed at each time point postcontrast by converting the T1 information to R 1 (R 1 = 1/T1). Since ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) was quantified temporally and between field strengths, the steady‐state distribution assumption was directly assessed along with the field dependence of Eq. [2]. Since direct measurements of hematocrit and myocardial extracellular volume fraction were not made, the precise value of r 1myo and r 1blood could not be quantified.

Statistics

The data are presented as the mean ± SD. Comparisons of measurement results between 1.5T and 3T were made by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and deemed significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Validation of T1 Measurement Technique in Phantoms

Measurements from the T1 maps of both T1 measurement techniques are shown in Table 1, and compared with the reference T1 measurements in the phantoms. Two‐parameter T1 fitting to the IRss images was determined with low error (relative to reference measurements), particularly for long T1s (>0.50 sec; <5% difference), which span the T1 values seen precontrast in vivo. The 2pt‐IR method yielded low error for T1 values in the range of 0.12–0.50 sec (<3% difference), which are similar to T1 values seen postcontrast in vivo. Accuracy for measuring long T1s using the 2pt‐IR method was compromised by the use of only three RR intervals between inversions.

Table 1.

Comparison of T1 Measurement Techniques in Phantoms

| Gd (mM) | T1ref (seconds) | IR‐ss 4pt (seconds) | IR 2pt (seconds) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meana | Meana | %diff | Meana | %diff | |

| 0 | 2.82 | 2.78 | −1.2 | 1.63 | −42.1 |

| 0.05 | 1.86 | 1.84 | −1.2 | 1.39 | −25.6 |

| 0.10 | 1.33 | 1.35 | 1.8 | 1.16 | −12.5 |

| 0.15 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 0.9 | 0.90 | −15.2 |

| 0.20 | 0.83 | 0.82 | −0.9 | 0.77 | −7.2 |

| 0.30 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.8 | 0.59 | −3.7 |

| 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 2.8 | 0.49 | −1.8 |

| 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 5.2 | 0.41 | −1.9 |

| 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 3.5 | 0.36 | 0.1 |

| 0.70 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 5.5 | 0.31 | 1.2 |

| 0.80 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 5.8 | 0.28 | 0.9 |

| 0.90 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 3.3 | 0.25 | −0.5 |

| 2.00 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 20.7 | 0.13 | 1.4 |

SD < 0.01.

IR‐SS 4pt = single‐shot IR b‐SSFP 4‐point (pre‐contrast), IR 2pt = segmented IR b‐SSFP 2‐point ratio method (post‐contrast).

For measuring very low T1s (<0.50 sec), IRss was not as accurate as the 2pt‐IR method. Even so, errors were low with the single‐shot technique for measuring T1 values typically seen postcontrast (<10% difference for 0.12 sec < T1 < 0.50 sec), suggesting its use for cases in which subject breath‐holding is an issue.

T1 Calculation In Vivo

The T1 measurement techniques were performed in all subjects without any complications. Since the TIs used precontrast ranged from 400 to 1500 msec spanning two heartbeats, some misregistration between images occurred despite the use of trigger delays. Therefore, fitting was performed using signal intensities from manually drawn ROIs. From the two‐parameter fit of the precontrast T1 measurement data, low fit errors were observed (r 2 > 0.95), while the 2pt‐IR produced T1 maps with no registration errors (Fig. 1). A histogram analysis of ROI measurements from the T1 maps (by measuring the SD within each ROI) resulted in 95% confidence intervals of ±7.3 msec and ±8.0 msec, respectively, for T1s measured using this technique (26).

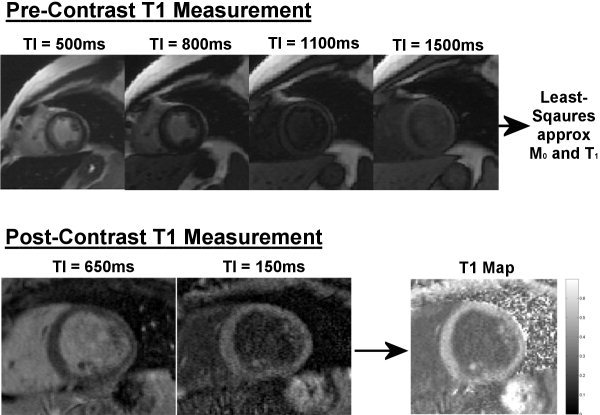

Figure 1.

Top: Precontrast T1 measurement of one subject using four separate IRss images at selected TIs. In vivo T1 was estimated using ROIs and a least‐squares approximation to Eq. [3]. Bottom: T1 calculation from a subject 15 minutes postinjection (0.2 mmol/kg) at 1.5T. The ratio method for calculating T1 involves two IR images using two different TIs: TIhigh = 650 msec and TIlow = 150 msec. The images were rescaled and then divided (TIhigh/TIlow) to produce an intensity‐ratio map. A T1 map was numerically calculated on a pixelwise basis using Eq. [4], assuming an appropriate T1 value.

Blood and myocardium T1 values pre‐ and postcontrast at 1.5T and 3T are summarized in Table 2, respectively. Precontrast T1 values for blood (N = 10) did not differ significantly between 1.5T and 3T despite a mean increase (1.5T: 1.58 ± 0.13 sec; 3T: 1.66 ± 0.06 sec; P > 0.05). Significant differences were observed between precontrast T1 values for myocardium (1.5T: 1.07 ± 0.03 sec; 3T: 1.22 ± 0.07 sec; N = 10, P < 0.05).

Table 2.

T1 Measurements (seconds) at 1.5T and 3T

| Dose (mmol/kg) | Time point (minute) | 1.5T | 3T | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Myocardium | Blood | Myocardium | ||

| 0.1 | 0 | 1.58 ± 0.14* | 1.07 ± 0.02 | 1.69 ± 0.03* | 1.20 ± 0.10 |

| 5 | 0.36 ± 0.08* | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.40 ± 0.04* | 0.54 ± 0.05 | |

| 10 | 0.40 ± 0.08* | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 0.47 ± 0.03* | 0.60 ± 0.03 | |

| 15 | 0.44 ± 0.08* | 0.59 ± 0.07 | 0.51 ± 0.06* | 0.63 ± 0.03 | |

| 20 | 0.48 ± 0.08* | 0.62 ± 0.06 | 0.54 ± 0.06* | 0.65 ± 0.02 | |

| 25 | 0.51 ± 0.08* | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 0.56 ± 0.06* | 0.67 ± 0.04 | |

| 30 | 0.54 ± 0.08 | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.06* | 0.70 ± 0.03 | |

| 35 | 0.55 ± 0.08* | 0.66 ± 0.06 | 0.62 ± 0.06* | 0.71 ± 0.03 | |

| 0.2 | 0 | 1.58 ± 0.14* | 1.05 ± 0.03 | 1.63 ± 0.07* | 1.24 ± 0.03 |

| 5 | 0.22 ± 0.06* | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 0.28 ± 0.04* | 0.42 ± 0.07 | |

| 10 | 0.28 ± 0.05* | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.07* | 0.48 ± 0.06 | |

| 15 | 0.31 ± 0.06* | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.07* | 0.49 ± 0.06 | |

| 20 | 0.33 ± 0.07* | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.07* | 0.57 ± 0.04 | |

| 25 | 0.36 ± 0.07* | 0.51 ± 0.05 | 0.44 ± 0.08* | 0.59 ± 0.06 | |

| 30 | 0.38 ± 0.07* | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.08* | 0.59 ± 0.06 | |

| 35 | 0.39 ± 0.07* | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 0.45 ± 0.07* | 0.59 ± 0.06 | |

P < 0.05, blood vs. myocardium.

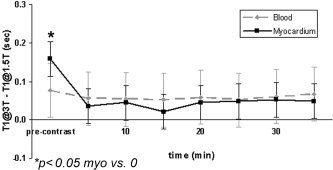

Following contrast injection there was a significant decrease in blood and myocardium T1 values at both field strengths and doses (P < 0.001). The mean postcontrast T1 values for blood and myocardium tended to be higher at 3T compared to 1.5T by 5–10% at each time point; however, the increase was not significant (P > 0.05). It was observed that the change in T1 from 1.5T to 3T was greater precontrast than postcontrast. Furthermore, the magnitude of the change between fields was relatively insensitive to the administered contrast dose, as determined from Table 2. T1 values were significantly lower at double dose (0.2 mmol/kg) than single dose at both field strengths (P < 0.05), but the change from 1.5T to 3T was the same for each dose. Figure 2 depicts these results by plotting the difference in T1 between fields (T1@3T – T1@1.5T) for blood and myocardium pre‐ and postcontrast. As shown, the difference in myocardium T1 between 1.5T and 3T seen prior to contrast injection (0.16 ± 0.06 sec, N = 10) was reduced by 72% (0.04 ± 0.06 sec, N = 10, P < 0.05) after 10 minutes. The amount of the reduction was almost constant over all time points and was insensitive to dose. A similar trend was observed in blood, but the decrease was 30% after 10 minutes.

Figure 2.

The plot compares pre‐ and postcontrast T1 differences between 1.5T and 3T (T1@3T – T1@1.5T) for all 10 subjects (combined 0.1 mmol/kg and 0.2 mmol/kg). The T1 difference between 1.5T and 3T decreases following contrast injection, and the decrease is more significant for myocardium than blood. Following contrast injection, the T1 difference remains relatively constant over time and is insensitive to dose and tissue type. Ten minutes postinjection the T1 difference decreased 72% for myocardium and 30% for blood. Although there was significant variability in T1 among subjects, the relaxation times at 3T were still generally greater than 1.5T.

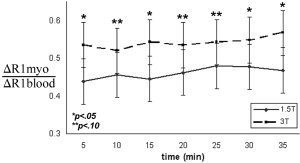

Contrast Agent Distribution

Figure 3 shows the cumulative ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) values for 0.1 mmol/kg and 0.2 mmol/kg. A constant value of ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) over time existed at both 1.5T and 3T, which confirms the fast‐exchange assumption by showing a steady‐state distribution of the contrast agent between blood and myocardium compartments. ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) did not differ significantly between single and double doses (1.5T (single and double): 0.49 ± .05 and 0.44 ± .06; 3T (single and double): 0.56 ± .05 and 0.53 ± .07, P > 0.05). Despite the constant value over time, a large difference in ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) was observed between 1.5T and 3T (0.46 ± .06 and 0.54 ± .06, P < 0.10). This implies that there may be a difference in compartmental contrast agent relaxivities (r 1myo and r 1blood) between field strengths (see Eq. [2]), assuming that the ratio of compartmental extracellular volumes (λmyo) did not change between 1.5T and 3T.

Figure 3.

The ratio of ΔR1 (ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood) exhibits constancy over time. This verifies that a steady state exists between compartments ([CA]myo = [CA]plasma). However, a measurable difference was observed between fields, which suggests that the compartmental influence of the contrast agent favors myocardium at 3T.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study were as follows: 1) the T1 of myocardium was 1.07 ± 0.03 sec at 1.5T and 1.22 ± 0.07 sec at 3T; 2) the T1 difference due to field strength (between 1.5T and 3T) was significantly reduced for myocardium, but not for blood, following contrast administration; 3) ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) differed between 1.5T and 3T, suggesting field and tissue dependence of the contrast agent relaxivity; and 4) there was significant inter‐subject variability in T1 postcontrast.

In all 10 subjects, the T1 of myocardium was 1.07 ± 0.03 sec at 1.5T and 1.22 ± 0.07 sec at 3 T, while blood T1 was 1.58 ± 0.13 sec at 1.5T and 1.66 ± 0.06 sec at 3T. The 3T values found in our study were roughly 8% higher than those reported by Noeske et al (2) (1.55 sec for blood and 1.12 sec for myocardium at 3T), which may reflect the different measurement techniques used. Noeske et al (2) utilized a partially refocused gradient‐echo in the steady‐state technique (GRASS) to measure T1 of myocardium and blood; however, they did not specify the segment TR and quantification method used. The T1 of blood at 1.5T was approximately 15–30% higher in our study compared to previously reported values (1.20 sec (3, 27), 1.23 sec (16), 1.38 sec (28), and 1.34 sec (29)), but lower than that observed in a recent study in pigs (1.80 sec (30)). However, these values may also dependon the measurement technique used. Klein et al (16) and Flacke et al (28) utilized a modified Look‐Locker technique that is known to measure T1* (31). It is also known that blood T1 at 1.5T depends strongly on hematocrit (32), with variations between 1.1–2.0 seconds for Hct variations of 0.6 and 0.2. The b‐SSFP readout module used with our method has been shown to be less sensitive to saturation effects than spoiled gradient‐echo techniques (e.g., fast low‐angle shot (FLASH)) due to the refocusing and reuse of transverse magnetization, which makes the sampling of free Mz recovery more accurate in IR experiments (33). This is because the decay rate of magnetization during b‐SSFP readout (E1*) is slower than that for FLASH (24, 28, 34). Because of this transient decay rate, the continuous sampling of the T1 relaxation curve using either b‐SSFP or FLASH requires appropriate correction of the measured T1 relaxation time, with more significant corrections needed when FLASH is used. Since our technique sampled T1 with discrete TIs using (relatively) short readout times, the majority of the signal intensity at ky = 0 evolved from the free IR preceding data acquisition, and thus the measured T1 was an accurate estimation of the true T1. Even so, the accuracy is a function of the applied flip angle and the number of excitations used during data acquisition, especially if a simplistic recovery expression like Eq. [3] is used to map signal intensities to T1. It can be shown (by using the full b‐SSFP expression (35)) that the error in estimation of T1 using IRss is relatively minor (<7%) over flip angles of 10–90° (assuming T1myo = 1100 msec, T2myo = 50 msec, T1blood = 1500 msec, T2blood = 250 msec). Furthermore, this measurement technique was assessed on phantoms of varying T1 values and resulted in accurate measurements compared to reference T1 values.

The postcontrast T1 values at 1.5T reported here are comparable to those obtained previously with the Look‐Locker method (16). The calculation of T1 maps using the 2pt‐IR method is limited by possible misregistration of the source images, which may cause erroneous measurements near tissue interfaces. This can be attributed to blurring from insufficient breath‐holding, or acquisitions during different phases of the cardiac cycle. Erroneous T1 measurements due to misregistration become significant if the technique is extended to individuals with small subendocardial infarcts. In this case, manually placed ROIs on the source images may be ideal.

The average difference in precontrast T1 between 1.5T and 3T was larger for myocardium (0.16 ± 0.06 sec) than blood (0.08 ± 0.13 sec). The fact that myocardium T1 increased more than blood from 1.5T to 3T may be attributed to the greater free water content and shorter molecular correlation times in blood (36), which would cause less field dependence on T1, in much the same way that water and CSF T1 appear almost insensitive to field change. The trend toward similar blood and myocardium T1 values at high field strength may lower image contrast between blood and myocardium on T1‐weighted images.

A dose of 0.2 mmol/kg caused T1 values to be significantly lower compared to 0.1 mmol/kg at both field strengths (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 2. However, the measured ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) did not differ significantly between single and double doses. As a result, the ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) data are shown cumulatively. The partition coefficient is not known to be dose dependent, since it is an inherent physiologic property. Relaxivity also should not be dose dependent. Indeed, different doses of Gd‐DTPA‐BMA in solution yield specific R 1 values (Table 1), and the slope of this relationship is equal to the relaxivity and is assumed to be constant.

All postcontrast T1 values were generally higher at 3T compared to 1.5T, but the change was neither significant nor constant over all subjects. Some subjects revealed a marked T1 change between fields (+0.15 sec), whereas others experienced only a subtle change at the same time point (∼0.06 sec). As a result, when data at each time point were analyzed cumulatively, there was no significant difference in blood and myocardium postcontrast T1 between 1.5T and 3T (Table 2). This observation reveals that the change in T1 seen prior to contrast administration is obscured following injection, possibly as a result of different contrast kinetic behavior among subjects, or a substantial T2* dephasing effect at 3T during T1 measurement. The former may be attributed to differences in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), left ventricular ejection fraction, or extracellular volumes among the subjects, while the latter may be due to field inhomogeneities and susceptibility effects. Although imaging procedures were implemented to reduce T2* dephasing (short TE), and the dose was identical at both field strengths, it is possible that the concentration of the contrast agent in circulation at any given time point was not the same during both study sessions. A difference in Gd‐DTPA‐BMA concentration among studies may be related to day‐to‐day changes in GFR that are largely controlled by food or fluid intake. Large differences in GFR among humans and dogs (37, 38) and over day‐to‐day periods (38) were recently observed. This degree of variation in postcontrast T1 measurements in vivo was also observed in previous studies (15, 16).

The ratio ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) at 1.5T was similar to values measured previously by MRI at 1.5T (16) and 2T (5, 15). These previous reports assumed that λmyo = ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t), which implies r1myo/r1blood = 1 (Eq. [2]). However, in the present study, there was an observable difference in ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) between 1.5T and 3T, which (from Eq. [2]) suggests there may be some tissue and field dependency of Gd‐DTPA‐BMA relaxivity (r 1). Previous investigations that directly quantified Gd‐DTPA relaxivity reported marginal decreases in r 1 in vivo and in vitro at high field strengths (39, 40, 41). Since explicit contrast agent concentrations were not determined in the present study, the relaxivity of Gd‐DTPA‐BMA in blood and myocardium (r 1blood and r 1myo, respectively) could not be directly calculated using serial R1 measurements (Eq. [1]). The ratio of compartmental relaxivities (r 1myo/r 1blood(t)) is only valid under the conditions of contrast agent steady state, which was confirmed by a constant value for ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t) over time. Even though Fig. 3 demonstrates this constancy at both 1.5T and 3T, it is apparent that a difference exists for this measure between the two field strengths (P < 0.10). Using approximate values of fECV = 0.35 and Hct = 0.40 (15), λmyo = fECV/(1 − Hct) ≈ 0.58 in Eq. [2], making r 1myo/r 1blood approximately 0.80 at 1.5T and 0.93 at 3T. It can be inferred from these data, therefore, that the relaxivity of Gd‐DTPA‐BMA may be greater in blood than in myocardium (r 1myo/r 1blood(t) < 1). Similarly, using Eq. [1], the ratio of ΔR 1(t) between 1.5T and 3T can be determined in the same individual for either blood or myocardium to reveal the field dependence of r 1: ΔR1(t)1.5T/ΔR1(t)3T=r1.5T/r3T. It can be shown with this equation that r 1.5T/r 3T is 1.18 ± 0.15 in blood and 1.01 ± 0.10 in myocardium, implying that the relaxivity in blood may decrease with field strength (r 1.5T/r 3T > 1) while the relaxivity in myocardium remains constant. However, because of the broad range of measured myocardial extracellular volumes (0.25–0.40 (5, 15, 16, 42)), there will be uncertainty in generalizing r 1myo/r 1blood and r 1.5T/r 3T without precise measurements of Hct or λmyo.

Longer T1s will exist at higher fields in a given individual, even after injection of a contrast agent. Thus, for imaging sequences that rely on preparation pulses, such as inversion and saturation recovery, it is simpler to suppress longer T1s because the slope of magnetization recovery becomes shallower as it crosses or originates from zero, allowing some leeway in TI selection. However, this may also decrease image contrast if the other tissue of interest is also suppressed. Our results suggest that the possible decrease in blood r 1 seen at 3T would produce lower image contrast between blood and myocardium postcontrast at 3T relative to 1.5T. This may have significance in delayed enhancement imaging at 3T, since image contrast will likely decrease between blood and normal myocardium after normal myocardium is suppressed using IR. However, this may benefit image contrast between enhanced infarct tissue and blood for delineating subendocardial infarcts. Unfortunately, predictions can not be made at this time about the field‐dependent behavior of contrast‐enhanced infarct tissue.

In conclusion, T1 increased from 1.5T to 3T, and more significantly for myocardium than blood. Following contrast administration, T1 differences between 1.5T and 3T were obscured by field and contrast agent effects such that there was no significant difference in T1 between 1.5T and 3T following contrast injection. The ratio of contrast agent distribution (ΔR 1myo/ΔR 1blood (t)) exhibited some field dependence, which suggests that contrast agent relaxivity may also be field dependent. These factors may play a role in the reduced T1 difference observed between 1.5T and 3T.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wen H, Denison TJ, Singerman RW, Balaban RS. The intrinsic signal‐to‐noise ratio in human cardiac imaging at 1.5, 3, and 4T. J Magn Reson 1997; 125: 65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Noeske R, Seifert F, Rhein KH, Rinneberg H. Human cardiac imaging at 3T using phased array coils. Magn Reson Med 2000; 44: 978–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenman RL, Shirosky JE, Mulkern RV, Rofsky NM. Double inversion black‐blood fast spin‐echo imaging of the human heart: a comparison between 1.5T and 3.0T. Magn Reson Imaging 2003; 17: 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stuber M, Botnar RM, Fischer SE, et al. Preliminary report on in vivo coronary MRA at 3 Tesla in humans. Magn Reson Med 2002; 48: 425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arheden H, Saeed M, Higgins CB, et al. Measurements of the distribution volume of gadopentetate dimeglumine at echo‐planar MR imaging to quantify myocardial infarction: comparison with Tc‐DTPA autoradiography in rats. Radiology 1999; 211: 698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weinmann HJ, Laniado M, Mutzel W. Pharmacokinetics of Gd‐DTPA/dimeglumine after intraveneous injection into healthy volunteers. Physio Chem Phys Med NMR 1984; 16: 167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prato FS, Wisenberg G, Marshall TP, Uksik P, Zabel P. Comparison of the biodistribution of gadolinium‐153 DTPA and technetium‐99m DTPA in rats. J Nucl Med 1988; 29: 1683–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dedieu V, Finat‐Duclos F, Renou JP, Joffre F, Vincensini D. In vivo tissue extracellular volume fraction measurement by dynamic spin‐lattice relaxometry: application to the characterization of muscle fiber types. Invest Radiol 1999; 34: 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Strich G, Hagan PL, Gerber KH, Slutsky RA. Tissue distribution and magnetic resonance spin‐lattice relaxation effects of gadolinium‐DTPA. Radiology 1985; 154: 723–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oksendal AN, Hals PA. Biodistribution and toxicity of MR imaging contrast media. J Magn Reson Imaging 1993; 3: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rehwald WG, Fieno DS, Chen EL, Kim RJ, Judd RM. Myocardial magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent concentrations after reversible and irreversible ischemic injury. Circulation 2002; 105: 224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jezzard P, Duewell S, Balaban RS. MR relaxation times in human brain: measurement at 4 T. Radiology 1996; 199: 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Henriksen O, de Certaines JD, Spisni A, Cortsen M, Muller RN, Ring PB. In vivo field dependence of proton relaxation times in human brain, liver and skeletal muscle: a multicenter study. Magn Reson Imaging 1993; 11: 851–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Block RE, Maxwell GP. Proton magnetic resonance studies of water in normal and tumor rat tissue. J Magn Reson 1974; 14: 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wendland MF, Saeed M, Lauerma K, et al. Alterations in T1 of normal and reperfused infarcted myocardium after Gd‐BOPTA versus Gd‐DTPA on inversion recovery EPI. Magn Reson Med 1997; 37: 448–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klein C, Nekolla SG, Balbach T, et al. The influence of myocardial blood flow and volume of distribution on late Gd‐DTPA kinetics in ischemic heart failure. J Magn Reson Imaging 2004; 20: 588–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elster AD. How much contrast is enough? Dependence of enhancement on field strength and MR pulse sequence. Eur Radiol 1997; 7(Suppl 5): 276–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tweedle MF, Wedeking P, Telser J, et al. Dependence of MR signal intensity on Gd tissue concentration over a broad dose range. Magn Reson Med 1991; 22: 191–194; discussion 195–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xie D, Kennan RP, Gore JC. Measurements of the relaxivity of gadolinium chelates in tissues in vivo. In: Proceedings of the 9th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Glasgow, Scotland, 2001. Abstract 890.

- 20. Rinck PA, Muller RN. Field strength and dose dependence of contrast enhancement by gadolinium‐based MR contrast agent. Eur Radiol 1999; 9: 998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pickup S, Wood AK, Kundel HL. Gadodiamide T1 relaxivity in brain tissue in vivo is lower than in saline. Magn Reson Med 2005; 53: 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stanisz GJ, Henkelman RM. Gd‐DTPA relaxivity depends on macromolecular content. Magn Reson Med 2000; 44: 665–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chung YC, Kellman P, Lee D, Simonetti O. A fast, TI insensitive infarct imaging technique. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2003; 5: 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schmitt P, Griswold MA, Jakob PM, et al. Inversion recovery TrueFISP: quantification of T1, T2 and spin density. Magn Reson Med 2004; 51: 661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sharma P, Patel S, Pettigrew RI, Oshinski JN. Measurements of relaxivity (R1) post contrast in patients with prior myocardial infarction. In: Proceedings of the 11th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Toronto, Canada, 2003. Abstract 634.

- 26. Haacke EM, Brown RW, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R. Magnetic resonance imaging: physical principles and sequence design. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. 914 p. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Simonetti OP, Finn JP, White RD, Laub G, Henry DA. “Black blood” T2‐weighted inversion‐recovery MR imaging of the heart. Radiology 1996; 199: 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Flacke SJ, Fischer SE, Lorenz CH. Measurement of the gadopentetate dimeglumine partition coefficient in human myocardium in vivo: normal distribution and elevation in acute and chronic infarction. Radiology 2001; 218: 703–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saeed M, Higgins CB, Geschwind JF, Wendland MF. T1‐relaxation kinetics of extracellular, intracellular and intravascular MR contrast agents in normal and acutely reperfused infarcted myocardium using echo‐planar MR imaging. Eur Radiol 2000; 10: 310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wagenseil JE, Johansson LO, Lorenz CH. Characterization of T1 relaxation time and blood‐myocardial contrast enhancement of NC100150 injection in cardiac MRI. J Magn Reson 1999; 10: 784–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pickup S, Wood AK, Kundel HL. A novel method for analysis of TOMROP data. J Magn Reson Imaging 2004; 19: 508–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Janick PA, Hackney DB, Grossman RI, Asakura T. MR imaging of various oxidation states of intracellular and extracellular hemoglobin. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1991; 12: 891–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Scheffler K, Hennig J. T1 quantification with inversion recovery TrueFISP. Magn Reson Med 2001; 45: 720–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Scheffler K. On the transient phase of balanced SSFP sequences. Magn Reson Med 2003; 49: 781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hargreaves BA, Vasanawala SS, Pauly JM, Nishimura DG. Characterization and reduction of the transient response in steady‐state MR imaging. Magn Reson Med 2001: 46: 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bloembergen N, Purcell EM, Pound RV. Relaxation effects in nuclear magnetic resonance absorption. Phys Rev 1948; 73: 679–710. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kampa N, Bostrom I, Lord P, Wennstrom U, Ohagen P, Maripuu E. Day‐to‐day variability in glomerular filtration rate in normal dogs by scintigraphic technique. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 2003; 50: 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hackstein N, Heckrodt J, Rau WS. Measurement of single‐kidney glomerular filtration rate using a contrast‐enhanced dynamic gradient‐echo sequence and the Rutland‐Patlak plot technique. J Magn Reson Imaging 2003; 18: 714–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Donahue KM, Burstein D, Manning WJ, Gray ML. Studies of Gd‐DTPA relaxivity and proton exchange rates in tissue. Magn Reson Med 1994; 32: 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bernstein MA, Huston J 3rd, Lin C, Gibbs GF, Felmlee JP. High‐resolution intracranial and cervical MRA at 3.0T: technical considerations and initial experience. Magn Reson Med 2001; 46: 955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Takahashi M, Uematsu H, Hatabu H. MR imaging at high magnetic fields. Eur J Radiol 2003; 46: 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Diesbourg LD, Prato FS, Wisenberg G, et al. Quantification of myocardial blood flow and extracellular volumes using a bolus injection of Gd‐DTPA: kinetic modeling in canine ischemic disease. Magn Reson Med 1992; 23: 239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]