Abstract

Acute respiratory infections are a major cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. Using multiplex PCR/RT‐PCR methods for the detection of 18 respiratory viruses, the circulation of those viruses during 3 consecutive dry seasons in Cambodia was described. Among 234 patients who presented with influenza‐like illness, 35.5% were positive for at least one virus. Rhinoviruses (43.4%), parainfluenza (31.3%) viruses and coronaviruses (21.7%) were the most frequently detected viruses. Influenza A virus, parainfluenza virus 4 and SARS‐coronavirus were not detected during the study period. Ninety apparently healthy individuals were included as controls and 10% of these samples tested positive for one or more respiratory viruses. No significant differences were observed in frequency and in virus copy numbers for rhinovirus detection between symptomatic and asymptomatic groups. This study raises questions about the significance of the detection of some respiratory viruses, especially using highly sensitive methods, given their presence in apparently healthy individuals. The link between the presence of the virus and the origin of the illness is therefore unclear. J. Med. Virol. 82:1762–1772, 2010. © 2010 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: multiplex PCR, respiratory virus, influenza‐like illness, asymptomatic individuals

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory infections are the leading cause of acute illnesses and a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for approximately two million deaths each year in infants [The World Health Report, 2004; Kieny and Girard, 2005; Mizgerd, 2006]. Acute respiratory infections are also associated with high mortality in the elderly and individuals with compromised cardiac, pulmonary, or immune systems. Clinical manifestations in respiratory infections range from self‐limited upper respiratory tract infections to more serious lower respiratory tract infections. Determining etiological diagnoses for patients with respiratory symptoms remains a clinical and laboratory challenge. Most laboratory‐confirmed viral infections are attributed to respiratory syncytial viruses (RSV), parainfluenza viruses (PIV), influenza viruses A and B (IAV, IBV), human rhinoviruses (HRhV), and adenoviruses (AdV). Clinical virology laboratories have used historically traditional methods such as direct fluorescent‐antibody assay (DFA) for the diagnosis of viral respiratory tract infections, however, these methods fail to detect a large proportion of infections.

Over the past 10 years, nucleic acid amplification techniques have been developed for several respiratory viruses. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and reverse transcription‐PCR (RT‐PCR) assays provide rapid results with equivalent or greater sensitivity than conventional methods [Erdman et al., 2003; Weinberg et al., 2004]. Furthermore, multiplex PCR assays have been used to detect the presence of two or more respiratory viruses in a single reaction tube [Fan et al., 1998; Coiras et al., 2004; Bellau‐Pujol et al., 2005.

Recent advances in molecular technology have enabled the detection of several new viral agents in specimens collected from human respiratory tracts, including the human metapneumovirus (HMPV) in 2001 [van den Hoogen et al., 2001], the severe acute respiratory syndrome‐associated coronavirus (SARS‐CoV) in 2003 [Ksiazek et al., 2003], the human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV‐NL63) in 2004 [van der Hoek et al., 2004], the human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV‐HKU1) in 2005 [Woo et al., 2005], as well as the human bocavirus (HBoV) in 2005 [Allander et al., 2005]. However, data regarding the prevalence of respiratory viruses in the community are still lacking in many parts of the world.

In order to assess the distribution of the major viral agents responsible for acute respiratory infections in Cambodia, respiratory specimens were tested retrospectively for 18 respiratory viruses using multiplex PCR assays. In addition, asymptomatic individuals were also tested in order to evaluate the importance of asymptomatic carriers of respiratory viruses and the significance of the detection of some viruses in the human respiratory tract.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Respiratory Specimens

For this study, 324 nasopharyngeal swab specimens were collected in children and adults between February and May (the dry season in Cambodia) over a 3‐year period (2005–2007). Nasopharyngeal swabs was collected in 1 mL of viral transport medium and stored at −80°C prior to testing.

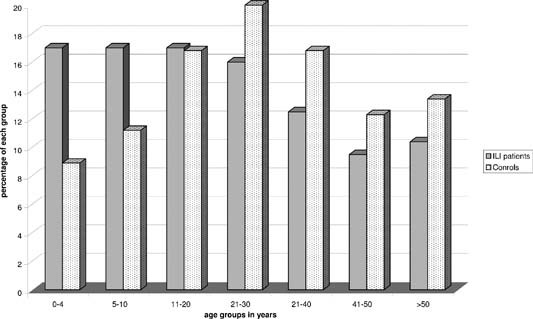

Two hundred thirty four symptomatic patients were recruited in five different provincial hospitals. When sufficient specimens were available in an age group, they were randomly chosen. Otherwise, all samples were tested (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Sample distribution by age group of influenza‐like illness patients and control individuals.

The inclusion criteria followed the World Health Organization (WHO) case definition for influenza‐like illness: sudden onset of a fever over 38°C and cough or sore throat and absence of other diagnoses [WHO, 2008].

The negative control group included 90 specimens collected from apparently healthy individuals, who were sampled only because they had contact with H5N1‐infected patients (such as family members and healthcare workers) between March and April 2005, 2006, and 2007 (Fig. 1). None of them declared having fever or any upper or lower respiratory symptom at the time of sampling. All the specimens were anonymized and not linked to the identity of any person.

RNA/DNA Preparation

RNA was extracted from 140 µl of nasopharyngeal secretion collected in viral transport medium, using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (QIAGEN®, Hilden, Germany). For DNA viruses (HBoV, AdV), nucleic acid was extracted from 200 µl of specimen using the MagNA Pure Compact Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit I (Roche Diagnostic®, Mannheim, Germany) on a MagNA Pure Compact instrument (Roche Diagnostic®).

Multiplex PCR/RT‐PCR

Five multiplex PCR/RT‐PCR methods, targeting 18 respiratory viruses, were used. IAV, IBV, HMPV (A and B), and RSV (A and B) were detected by the multiplex RT‐PCR 1; PIV‐1, ‐2, ‐3, and ‐4 by the multiplex RT‐PCR 2; HRhV, enterovirus (EnV), influenza C virus (ICV) and SARS‐CoV by the multiplex RT‐PCR 3; HCoV‐OC43, ‐229E, ‐NL63 and ‐HKU1 by the multiplex RT‐PCR 4; AdV and HBoV by the multiplex PCR 5 (Table I).

Table I.

Primer Sequences Used in the 5 Multiplex PCR/RT‐PCR

| Virus | Assay | Primer designation | Primer sequences (5′–3′) | Expected amplicon size (bp) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex 1 | |||||

| IAV | RT‐PCR | A1 (For) | CAG AGA CTT GAA GAT GTC TTT GCT (A)G | 212 |

Adapted from Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

| A2 (Rev) | GCT CTG TCC ATG TTA TTT GG(A) ATC |

Adapted from Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| Hemi nested | MIA3 (For) | CTC TGA CTA AGG GGA TTT TG | 130 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| A2 (Rev) | GCT CTG TCC ATG TTA TTT GG(A) ATC |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| IBV | RT‐PCR | B1 (For) | GAA AAA TTA CAC TGT TGG TTC GGT G | 365 |

Adapted from Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

| B2B (Rev) | AGC GTT CCT AGT TTT ACT TGC ATT GA |

Adapted from Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| Hemi nested | MIB3 (Rev) | CAT GAA ARC TCA CAC ATC T | 260 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| B1 (For) | GAA AAA TTA CAC TGT TGG TTC GGT G |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| RSV | RT‐PCR | Cane P1 (For) | GGA ACA AGT TGT TGA GGT TTA TGA ATA TGC | 278 |

Adapted from Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

| Cane P2 (Rev) | CTG CTG TCA AGT CTA GTA CAC TGT AGT |

Adapted from Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| Hemi nested | VRSi (Rev) | GGT GTA CCT CTG TAC TCT C | 180 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| Cane P1 (For) | GGA ACA AGT TGT TGA GGT TTA TGA ATA TGC |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| HMPV | RT‐PCR | MPV M1a (For) | GGA GTC CTA CCT AGT AGA C | 537 | Freymuth F [unpublished work] |

| MPV M2 (Rev) | GCA GCT TCA ACA GTA GCT G |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| Hemi nested | MPV M3 (For) | AGG CCA ACA CAC CAC CAG | 410 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| MPV M2 (Rev) | GCA GCT TCA ACA GTA GCT G |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| Multiplex 2 | |||||

| PIV‐1 | RT‐PCR | PiS1+ (For) | CCG GTA ATT TCT CAT ACC TAT G | 317 | Echevarria et al. 1998 |

| PiS1‐(Rev) | CTT TGG AGC GGA GTT GTT AAG | Echevarria et al. 1998 | |||

| Hemi nested | piS1i (For) | AGC TGC AGG AAC AAG GGG | 261 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| PiS1‐(Rev) | CTT TGG AGC GGA GTT GTT AAG |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| PIV‐2 | RT‐PCR | PiP2+ (For) | AAC AAT CTG CTG CAG CAT TT | 507 | Echevarria et al. 1998 |

| PiP2‐ (Rev) | ATG TCA GAC AAT GGG CAA AT | Echevarria et al. 1998 | |||

| Hemi nested | PARA2i (For) | CTA GCT GAA CTG AGA CTT G | 340 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| PiP2‐ (Rev) | ATG TCA GAC AAT GGG CAA AT |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| PIV‐3 | RT‐PCR | P3‐1 (For) | CTC GAG GTT GTC AGG ATA TAG | 189 | Karron et al. 1994 |

| P3‐2 (Rev) | CTT TGG GAG TTG AAC ACA GTT | Karron et al. 1994 | |||

| Hemi nested | PARA3i (Rev) | GCT AGA GAA CAT GAC TTC C | 145 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| P3‐1 (For) | CTC GAG GTT GTC AGG ATA TAG |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| PIV‐4 | RT‐PCR | Pi4S+ (For) | CTG AAC GGT TGC ATT CAG GT | 451 | Aguilar et al. [2000] |

| Pi4S‐ (Rev) | TTG CAT CAA GAA TGA GTC CT | Aguilar et al. [2000] | |||

| Hemi nested | Pi4i (Rev) | GTC TGA TCC CAT AAG CAG C | 390 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| Pi4S+ (For) | CTG AAC GGT TGC ATT CAG GT |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| Multiplex 3 | |||||

| ICV | RT‐PCR | CHAA (For) | ACA CTT CCA ACC CAA TTT GG | 485 | Zhang and Evans 1991 |

| CHAD (Rev) | CCT GAC AGC AAC TCC C TC AT | Zhang and Evans 1991 | |||

| Hemi nested | MICi (For) | GAG GAT GTG GCA ACT ACT | 391 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| CHAD (Rev) | CCT GAC AGC AAC TCC C TC AT |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| HRhV | RT‐PCR | SRHI 1 (For) | GCA TCI GGY ARY TTC CAC CAC CAN CC | 549 | Savolainen et al. 2002 |

| SRHI 2 (Rev) | GGG ACC AAC TAC TTT GGG TGT CCG TGT | Savolainen et al. 2002 | |||

| Hemi nested | NESTRHI1 (Rev) | ATG GGN GCW CAN GTN TCH ANH CA | 450 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| SRHI 1 (For) | GCA TCI GGY ARY TTC CAC CAC CAN CC |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| SARS‐CoV | RT‐PCR | SARS‐Bin out‐AS (For) | CAT AAC CAG TCG GTA CAG CTA | 195 | Drosten et al. 2003 |

| SARS‐Bin out‐S2 (Rev) | RTG AAT TAC CAA GTC AAT GGT | Drosten et al. 2003 | |||

| Nested | SARS‐Bni/ in‐AS (For) | CTG TAG AAA ATC CTA GCT GGA | 110 | Drosten et al. 2003 | |

| SARS‐Bni/in‐S (Rev) | GAA GCT ATT CGT CAC GTT CG | Drosten et al. 2003 | |||

| Multiplex 4 | |||||

| HCoV‐OC43 | RT‐PCR | MF 1 (For) | GGC TTA TGT GGC CCC TTA CT | 334 |

Vabret et al. 2001 |

| MF3 (Rev) | GGC AAA TCT GCC CAA GAA TA |

Vabret et al. 2001 |

|||

| Hemi nested | MF2i (Rev) | CTC CAA AAA CTT CCA GTT C | 170 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| MF 1 (For) | GGC TTA TGT GGC CCC TTA CT |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| HCoV‐229E | RT‐PCR | MD1 (For) | TGG CCC CAT TAA AAA TGT GT | 574 |

Vabret et al. 2001 |

| MD3 (Rev) | CCT GAA CAC CTG AAG CCA AT |

Vabret et al. 2001 |

|||

| Hemi nested | MD2i (Rev) | CCG TAT CAA CAC TCG TTA TGT GG | 230 |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|

| MD1 (For) | TGG CCC CAT TAA AAA TGT GT |

Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005 |

|||

| HCoV‐HKU1 | RT‐PCR | HKU‐N‐sens3 (For) | ATC TGA GCG AAA TTA CCA AAC | 443 |

Woo et al. 2005 |

| HKU1 antisense (Rev) | CGG AAA CCT AGT AGG GAT AGC TT |

Woo et al. 2005 |

|||

| HCoV‐NL63 | RT‐PCR | NL63 sens (For) | GAT AAC CAG TGG AAG TCA CCT AGT TC | 255 |

Vabret et al. 2005 |

| NL63 antisense (Rev) | ATT AGG AAT CAA TTC AGC AAG CTG TG |

Vabret et al. 2005 |

|||

| Multiplex 5 | |||||

| AdV | PCR | ADHEX1F (For) | CAA CAC CTA YGA STA CAT GAA | 270 |

Avellon et al. 2001 |

| ADHEX2R (Rev) | ACA TCC TTB CKG AAG TTC CA | Palacious et al. [2003] | |||

| HBoV | PCR | 188F (For) | GAS CTC TGT AAG TAC TAT TAC | 354 |

Allander et al. 2005 |

| 542R (Rev) | CTC TGT GTT GAC TGA ATA CAG |

Allander et al. 2005 |

|||

Multiplex RT‐PCR 1, 2, 3 are a single‐step combined PCR amplification performed using the One‐step RT‐PCR kit from Qiagen, as described previously [Bellau‐Pujol et al., 2005]. However, multiplex 3 was modified by including the detection of SARS‐CoV instead of HCoV‐NL63 and HCoV‐229E. The multiplex 4 was developed for the simultaneous detection of the four HCoVs using primers described by others [Vabret et al., 2001, 2005; Woo et al., 2005].

The four assays were undertaken in 30 µl reaction volume containing 3 µl RNA extract, 6 µl Qiagen OneStep RT‐PCR buffer 5×, 1.2 µl 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 1 µl Qiagen OneStep RT‐PCR Enzyme Mix (OneStep RT‐PCR kit, Qiagen), 1.44 µl of each primer (concentration 10 µM), 3.6 µl Qiagen OneStep RT‐PCR kit Q solution, and RNase‐free water to complete the 30 µl final volume. The reaction was carried out in a MyCycler thermo‐cycler (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with an initial reverse transcription step at 50°C for 30 min, followed by PCR activation at 94°C for 15 min, 8 initial cycles of amplification (30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 58°C, 1 min at 72°C), 30 additional cycles of amplification (30 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 50°C, 1 min at 72°C) and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min.

The multiplex PCR 5 was designed for the detection of DNA viruses using primers described by others [Allander et al., 2005; Bellau‐Pujol et al., 2005; Casas et al., 2005]. Multiplex 5 is a single‐step combined PCR amplification. The 25 µl reaction mix consisted of 2.5 µl DNA extract, 2.5 µl 10× PCR buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), 0.5 µl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.5 µl of 5 U/µl Taq DNA Polymerase (Promega) 1 µl of each primer (concentration: 10 µM), 2.5 µl of MgCl2 25 mM, and RNase‐free water to a final volume of 25 µl. The reaction was carried out in a MyCycler thermo‐cycler (Bio‐Rad Laboratories). After 2 min at 94°C, 40 cycles of amplification (94°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min) were performed, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min.

Hemi‐nested or nested singleplex PCR methods were used to confirm positive results obtained by multiplex RT‐PCR. Products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel. Primer sequences used in these protocols are listed in Table I.

In vitro‐transcribed RNA was generated from different viruses to use as positive controls and to assess the sensitivity of each multiplex PCR/RT‐PCR (Table II). The PCR‐amplified fragments of each virus were inserted into the pGEM‐T Easy Vector (Promega). The plasmid T7 RNA polymerase transcription initiation site and promoter sequence located upstream of viral cloned sequences were utilized for in vitro synthesis of RNA transcripts, using RiboMAX™ Large Scale RNA Production System‐T7 (Promega) following the instructions of the manufacturer. The concentration of each RNA transcript was measured by an ND‐1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). To assess sensitivity, RNA was serially diluted (10‐fold), ranging from 105 to 1 RNA copies/reaction (Table II). The specificity of multiplex 1, 2, and 3 (which did not initially test for SARS‐CoV) was assessed by Bellau‐Pujol et al. 2005] who did not observe false positives. For multiplex 3, 4, and 5, the analytical specificity was checked by including the following in each RT‐PCR/PCR: an appropriate positive control, two negative controls, a strain of Mycoplasma pneumonia and a strain of Chlamydia pneumonia, two nucleic acids extracted from clinical specimens and confirmed by sequencing or two RNA transcripts for: influenza A/H1N1, H3N2, H5N1 and H1N1 pandemic, influenza B, influenza C, RSV, HMPV, PIV‐1, ‐2, ‐3, ‐4, HRhV, EnV, HCoV‐OC43, ‐229E, ‐NL63, ‐HKU1, SARS‐CoV, AdV, and HBoV. Non‐specific amplifications were not observed (data not shown).

Table II.

Sensitivity of Monoplex and Multiplex PCR/RT‐PCR

| Multiplex | Virus | Expected amplicon size (bp) | Sensitivity of monoplex PCR/RT‐PCR (number of copy/µl of VTMa) | Sensitivity of multiplex PCR/RT‐PCR (number of copy/µl of VTMa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IAV | 212 | 4 | 4 |

| IBV | 365 | 4 | 36 | |

| RSV | 278 | 4 | 36 | |

| HMPV | 537 | 4 | 4 | |

| 2 | PIV‐1 | 317 | 36 | 3572 |

| PIV‐2 | 507 | 358 | 3572 | |

| PIV‐3 | 189 | 4 | 36 | |

| PIV‐4 | 451 | 4 | 358 | |

| 3 | ICV | 485 | 4 | 36 |

| HRhV | 549 | 358 | 358 | |

| SARS | 195 | 4 | 4 | |

| 4 | HCoV‐OC43 | 335 | 4 | 4 |

| HCoV‐229E | 573 | 4 | 4 | |

| HCoV‐HKU1 | 443 | 4 | 4 | |

| HCoV‐NL63 | 255 | 358 | 358 | |

| 5 | AdV | 270 | 36 | 36 |

| HBoV | 354 | 4 | 4 |

Viral transport medium.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using the Stata/SE version 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Significance was assigned at P < 0.05 for all parameters. Uncertainty was expressed at 95% confidence intervals. The t student, Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis rank tests were used for continuous variables and χ 2 and Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables.

RESULTS

A total of 324 nasopharyngeal swabs were tested including 234 (72%) among patients who presented with influenza‐like illness and 90 (28%) in controls. Patients with influenza‐like illness were significantly younger than apparently healthy control individuals (mean age 22.5 vs. 28.5 years, P = 0.001).

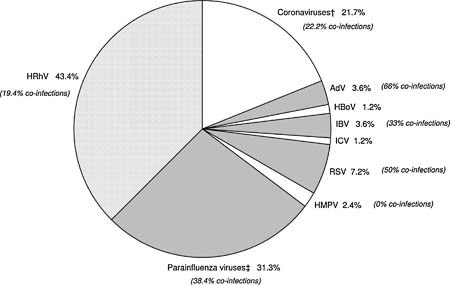

Among the 234 influenza‐like illness patients tested by multiplex PCR/RT‐PCR, 83 (35.5%) were positive for at least one of the respiratory viruses tested (Tables IIIa, IIIb, IIIc). Of these, HRhV (43.4%), PIVs 1–3 (31.3%) and various HCoVs (21.7%) accounted for most of the etiologies of influenza‐like illness. Other viruses associated with influenza‐like illness are highlighted in Figure 2. Of note, PIV‐4, IAV, and SARS‐CoV were not detected during the study period.

Table IIIa.

Number of Detections (% of Total Samples) of Respiratory Viruses Among Influenza‐Like Illness (ILI) Patients and Asymptomatic Individuals

| IAV | IBV | VRS | HMPV | PIV‐1 | PIV‐2 | PIV‐3 | PIV‐4 | ICV | HRhV/EnV | SARS‐CoV | HCoV‐OC43 | HCoV‐229E | HCoV‐HKU1 | HCoV‐NL63 | AdV | HBoV | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILI patients | 0 | 3 (1.3) | 6 (2.6) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (2.6) | 3 (1.3) | 17 (7.3) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 36 (15.4) | 0 | 10 (4.3) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (1.7) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.4) | 83 (35.5) |

| Asymptomatic individuals | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (8.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 9 (10) |

Table IIIb.

Number of Detections (% of Total Samples) of Single Viral Infections by Age Group Among Influenza‐Like Illness (ILI) Patients/Asymptomatic Individuals

| Age groups | 0–4 years | 5–10 years | 11–20 years | 21–30 years | 31–40 years | 41–50 years | >50 years | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age characteristics | Average: 1.1; 95 CI: 0.9–1 | Average: 6.6; 95 CI: 6.1–7.1 | Average: 14.7; 95 CI: 13.7–15.7 | Average: 24.5; 95 CI: 23.7–25.3 | Average: 35.8; 95 CI: 34.5–37.0 | Average: 44.9; 95 CI: 43.5–46.2 | Average 60.9; 95 CI: 57.5–64.4 | |

| Average: 2.9; 95 CI: 2.0–3.7 | Average: 7.2; 95 CI: 6.4–8.2 | Average: 15.4; 95 CI: 13.8–16.9 | Average: 28.2; 95 CI: 26.8–29.6 | Average: 35; 95 CI: 33.2–36.8 | Average: 45.4; 95 CI: 43.7–47.2 | Average 59.3; 95 CI: 55.1–63.6 | ||

| Sample size | 40/8 | 45/11 | 38/15 | 36/18 | 29/15 | 22/11 | 24/12 | 234/90 |

| IAV | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| IBV | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (2.6)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (4.2)/0 | 2 (0.8)/0 |

| VRS | 1 (2.5)/0 | 2 (4.4)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 3 (1.3)/0 |

| HMPV | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (2.6)/0 | 0/0 | 1 (3.4)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2 (0.8)/0 |

| PIV‐1 | 0/0 | 2 (4.4)/0 | 2 (5.3)/0 | 1 (2.8)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 5 (2.1)/0 |

| PIV‐2 | 0/0 | 1 (2.2)/0 | 1 (2.6)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2 (0.8)/0 |

| PIV‐3 | 2 (5)/0 | 3 (6.7)/0 | 2 (5.3)/0 | 1 (2.8)/0 | 0/0 | 1 (4.5)/0 | 0/0 | 9 (3.8)/0 |

| PIV‐4 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| ICV | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (4.5)/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/0 |

| HRhV/EnV | 7 (17.5)/0 | 9 (20)/3 (27.3) | 6 (15.8)/2 (13.3) | 4 (11.1)/3 (16.7) | 0/0 | 1 (4.5)/0 | 2 (8.3)/0 | 29 (12.4)/8 (8.9) |

| SARS‐CoV | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| HCoV‐OC43 | 3 (7.5)/0 | 4 (8.9)/0 | 1 (2.6)/0 | 1 (2.8)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 9 (3.8)/0 |

| HCoV‐229E | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (2.6)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/0 |

| HCoV‐HKU1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (2.8)/0 | 1 (3.4)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2 (0.8)/0 |

| HCoV‐NL63 | 0/0 | 2 (4.4)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2 (0.8)/0 |

| AdV | 1 (2.5)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/0 |

| HBoV | 0/0 | 0/1 (9.1) | 1 (2.6)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/1 (1.1) |

| Total | 14 (35)/0 | 23 (51.1)/4 (36.4) | 15 (39.5)/2 (13.3) | 9 (25)/3 (16.7) | 2 (6.9)/0 | 3 (13.6)/0 | 3 (12.5)/0 | 69 (26.1)/9 (10) |

Table IIIc.

Number of Detections (% of Total Samples) of Viruses Detected in Co‐Infections Among Influenza‐Like Illness (ILI) Patients/Asymptomatic Individuals for Each Age Group

| Age groups | 0–4 years | 5–10 years | 11–20 years | 21–30 years | 31–40 years | 41–50 years | >50 years | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age characteristics | Average: 1.1; 95 CI: 0.9–1 | Average: 6.6; 95 CI: 6.1–7.1 | Average: 14.7; 95 CI: 13.7–15.7 | Average: 24.5; 95 CI: 23.7–25.3 | Average: 35.8; 95 CI: 34.5–37.0 | Average: 44.9; 95 CI: 43.5–46.2 | Average 60.9; 95 CI: 57.5–64.4 | |

| Average: 2.9; 95 CI: 2.0–3.7 | Average: 7.2; 95 CI: 6.4–8.2 | Average: 15.4; 95 CI: 13.8–16.9 | Average: 28.2; 95 CI: 26.8–29.6 | Average: 35; 95 CI: 33.2–36.8 | Average: 45.4; 95 CI: 43.7–47.2 | Average 59.3; 95 CI: 55.1–63.6 | ||

| Sample size | 40/8 | 45/11 | 38/15 | 36/18 | 29/15 | 22/11 | 24/12 | 234/90 |

| HRhV + PIV‐3 | 2 (5)/0 | 1 (2.2)/0 | 1 (2.6)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 4 (1.8)/0 |

| HRhV + HCoV‐NL63 | 1 (2.5)/0 | 0/0 | 1 (2.6)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2 (0.9)/0 |

| AdV + PIV‐1 | 1 (2.5)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/0 |

| AdV + PIV‐3 | 1 (2.5)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/0 |

| HCoV‐OC43 + PIV‐2 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (2.6)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/0 |

| HRhV + IBV | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (2.8)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/0 |

| PIV‐3 + RSV | 1 (2.5)/0 | 1 (2.2)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 2 (0.9)/0 |

| HRhV + RSV | 1 (2.5)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/0 |

| HRhV + PIV‐3 + HCoV‐229E | 1 (2.5)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1 (0.4)/0 |

| Total | 8 (20)/0 | 2 (4.4)/0 | 3 (7.9)/0 | 1 (2.8)/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 14 (6.0)/0 |

Figure 2.

Viral causes of influenza‐like illness among 83 patients (non‐mutually exclusive). †OC43 (55.5%); HKU1 (11.1%); NL63 (22.2%); 229E(11.1%). ‡PIV‐1 (23%); PIV‐2 (11.5%); PIV‐3 (65.4%).

Of 36 (15.4%) HRhVs detected in influenza‐like illness patients, seven (19.4%) were co‐infections with other viruses including 4 PIV‐3, 2 HCoV‐NL63, 1 IBV, 1 RSV and 1 PIV‐3 + CoV‐229E (Table IIIc). PIVs of different types were detected in 26 (11.1%) patients: PIV‐1 (23%), PIV‐2 (11.5%), and PIV‐3 (65.4%). Of these, 10 (38.4%) were co‐infected with other viruses including HRhV, RSV, AdV, and HCoV.

Of 18 (7.7%) influenza‐like illness patients with HCoVs, HCoV‐OC43 accounted for 55.5%, followed by HCoV‐NL63 (22.2%), HCoV‐HKU1 (11.1%), and HCoV‐229E (11.1%). Four (22.2%) HCoV‐infected patients were also infected with other viruses (HRhV and PIV‐2, ‐3).

Viruses were also detected in 9 (10%) of 90 control samples using multiplex (Tables IIIa and IIIc). HRhV was the most frequently detected (n = 8, 89%), and HBoV was identified in one case (11%). No co‐infections were observed in the control group (Table IIIc).

Among the 83 positive specimens collected from influenza‐like illness patients, 47 (57.3%) were obtained in children under 10 years old, 18 (21.7%) in the 11‐ to 20‐year age group, 10 (12.2%) in the 21‐ to 30‐year age group, 2 (2.4%) in the 31‐ to 40‐year age group, 3 (3.7%) in the 41‐ to 50‐year age group and 3 (3.7%) in adults aged over 50 years.

In 59% of cases, the three viruses detected most frequently (HRhV, PIVs, and HCoVs) affected children ≤10 years of age. Sixty‐one percent of HRhV infections were diagnosed in children ≤10 years of age (median age 7 years, mean 12.9, range from 3 months to 70 years) as well 61% of HCoV infections (median age 7.5 years, mean 10.7, range 3 months to 31 years) and also 61% of PIV infections (median age 7 years, mean age 9.8, range 3 months to 41 years). When excluding co‐infections, no significant differences in age were observed between the three groups of viruses (P > 0.05).

The frequency of HRhV detection in the patient group was not statistically different to the control group (P = 0.37). Within the patient group, no significant difference in frequency of HRhV infections between each age group was demonstrated (data not shown).

When considering the total number of positive cases in young children ≤10 years and in influenza‐like illness patients ≥11 years, the frequency of viruses detection was significantly higher in influenza‐like illness patients than in asymptomatic individuals (Table IV).

Table IV.

Comparison of Virus Detection Rates Between Age Groups Among Influenza‐Like Illness Patients/Asymptomatic Individuals

| Age group (years) | Sample size | Number of positive cases (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–10 | 85/19 | 47 (55.3)/4 (21.1) | 0.007 |

| ≥11 | 149/71 | 35 (23.5)/5 (7.0) | 0.003 |

To compare the relative quantity of HRhV and HBoV RNA and DNA in the samples from the patient group to the control group, extracted nucleic acids were diluted serially 10‐fold and re‐tested by RT‐PCR/PCR. In both the symptomatic group and the control group only one HBoV was detected. The limit of detection by PCR was a dilution of 1:10 in the control group and 1:1,000 in the patient group. For HRhV, no significant differences were observed in the detection limits between asymptomatic individuals and patients with an influenza‐like illness (Table V).

Table V.

Limit of Detection by RT‐PCR After Serial Dilutions of Samples Tested Positive for Rhinovirus in Influenza‐Like Illness (ILI) Patients and Asymptomatic Individuals

| Dilution | ILI patients | Asymptomatic individuals | P‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No dilution | 33 (100%) | 8 (100%) | |

| 1:10 | 2 (6.1%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.5337 |

| 1:100 | 13 (39.4%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.1500 |

| 1:1,000 | 8 (24.2%) | 2 (25%) | 0.9623 |

| 1:10,000 | 7 (21.2%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.3354 |

| >1:10,000 | 3 (9.1%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.7713 |

DISCUSSION

For the purpose of this study, published multiplex RT‐PCR methods were optimized and new multiplex PCR/RT‐PCR methods were developed using primers described in the literature. In our study, the multiplex approach, by comparison with a “monoplex” PCR or RT‐PCR, was sometimes associated with a decrease in sensitivity. Nevertheless, sensitivity was improved after optimization of the Freymuth's protocols, who demonstrated previously that the multiplex RT‐PCR represented a significant improvement over conventional methods [Freymuth et al., 2006]. The multiplex 4 and 5 developed for this study also allowed the detection of very low nucleic acid copy numbers, and therefore it was considered that these two methods are reasonably sensitive and specific for the detection of respiratory viruses.

While the case definition was intended to detect primarily influenza viruses, no influenza A cases was observed and IBV and ICV were found in only 4 (1.7%) patients. Recent data demonstrates that the seasonality of influenza virus transmission corresponds mostly to the rainy season and only a few cases can be detected during the dry season [Mardy et al., 2009].

Among specimens collected in patients with influenza‐like illness, despite the fact that the case definition used did not include the main symptoms observed during the common cold (often caused by the rhinovirus), the virus detected most frequently was still HRhV (15.4%). Almost all age groups were affected by this virus. These results are consistent with previous findings suggesting that the HRhV are one of the most frequent causes of acute respiratory infections in adults and children with a prevalence varying between 10% to more than 40% (Australia: 44.4%; Finland: 45%; Korea: 33.3%) [Tsolia et al., 2004; Arden et al., 2006; Chung et al., 2007].

Over 11% of the patients were positive for at least one of the PIVs (in comparison with 10.7% in Germany and 11.5% in Korea). PIV‐3 is the most frequent of all PIVs and one of the leading causes of respiratory infection in infants and young children. These results are in agreement with the published data [Gröndahl et al., 1999; König et al., 2004; Thomazelli et al., 2007; Yoo et al., 2007]. PIV‐1 and PIV‐2 were not detected frequently which is also consistent with other studies [Gröndahl et al., 1999; Thomazelli et al., 2007]. PIV‐4 was never detected and appears in general to be found rarely among Cambodian patients [Institut Pasteur du Cambodge, unpublished work].

HCoV was detected in 7.6% of the influenza‐like illness patients, which is comparable with data from other authors (France: 5.7%; Hong Kong: 2.1–4.4%), although target populations, inclusion criteria, seasonality, climate environment and diagnostic methods were different [Chiu et al., 2005; Lau et al., 2006; Vabret et al., 2008].

Due to the small sample sizes of each age group and the small number of viral infections, once stratified by age group the results should be interpreted with caution. It seems that HCoV‐NL63 and HCoV‐229E caused more infections in children <11 years and to a lesser extent in young adults <21 years (P = 0.054 and 0.143, respectively), while HCoV‐HKU1 had a slight tendency to infect adults ≥21 years (P = 0.51). HCoV‐OC43 was detected more often in children than in adults (P = 0.008) and was also the most frequent of the four HCoV identified during the study. The predominance of HCoV‐OC43 among the HCoV family has already been observed in other Asian countries [Lau et al., 2006].

Only six cases of RSV infection were detected, occurring in children ≤10 years (mean age 2.8 years, range 5 months to 7 years). Three single infections and three co‐infections were observed. RSV is usually the most important viral cause of lower respiratory tract infections among infants and young children in both developing and developed countries [Selwyn, 1990]; and also infects the elderly [Falsey et al., 2005]. RSV has a worldwide distribution, with outbreaks occurring yearly with an unusually predictable and regular pattern. In temperate climates, RSV causes annual epidemics during the winter months [Collins et al., 1996], while epidemiological data from tropical regions have shown an association between RSV outbreaks and rainy seasons [Weber et al., 1998; Loscertales et al., 2002]. As is the case for HMPV, the low prevalence of respiratory infections caused by RSV in this study might be explained by the fact that the study was conducted during the dry season, or that the influenza‐like illness definition does not fit well with symptoms observed during RSV infections.

According to the literature, HMPV is identified in 3% to nearly 20% of patients who suffer from acute respiratory infections, especially in children (Brazil: 17.8%; Germany: 18%; Hong Kong: 5.5%; Italy: 3,8%; Korea: 4.7%; Singapore: 5.3%) [Peiris et al., 2003; König et al., 2004; Choi et al., 2006; Loo et al., 2007; Thomazelli et al., 2007; Fabbiani et al., 2009]. The seasonal patterns of HMPV infections in tropical countries are not known. This study was conducted during the dry season only, which could explain why only two HMPV infections were detected. Indeed, recent data from a larger study confirmed that HMPV was responsible for infections in Cambodian patients but with a peak of transmission during the rainy season [Institut Pasteur du Cambodge, unpublished work]. In addition, the influenza‐like illness case definition is not well adapted for HMPV infections which are usually associated with low or no fever, rhino‐pharyngitis, and rarely cough.

Human AdV are usually responsible for up to 13% of acute respiratory tract infections (Australia: 6%; Brazil: 6.8%; Finland: 12%; Germany: 12.9%; Italia: 10.5%) [Gröndahl et al., 1999; Tsolia et al., 2004; Arden et al., 2006; Thomazelli et al., 2007; Fabbiani et al., 2009]. In Cambodia, only three samples (1.3%) were positive for AdV, and all were collected from patients under 5 years old. Similar prevalence was found in other Asian countries (China: 1.7%; Korea: 1.3%; Singapore: 0.3%) [Chung et al., 2007; Loo et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2008].

In Asia, the prevalence of HBoV in children experiencing acute respiratory infections is usually between 5% and 11% [Chung et al., 2006, 2007; Ma et al., 2006; Qu et al., 2007]. In Thailand, one of Cambodia's neighboring countries, a study recruiting patients from all ages showed that 3.9% of samples were positive for HBoV, and more commonly in children <4 years old [Fry et al., 2007]. In Cambodia, only one case was reported. The virus was detected in a 13‐year‐old adolescent. Additional studies are necessary to document the importance of HBoV as a viral agent responsible for respiratory infections.

Interestingly, HRhV and HBoV were also detected in individuals apparently healthy at the time of sample collection. HRhV appears to be as frequent in the control group as in the patient group, suggesting that these viruses can be detected in the respiratory tract without causing any symptoms and that the detection of these viruses is not necessarily associated with a disease. These results are consistent with other data demonstrating detection of HRhV and HBoV by RT‐PCR in 15–30% and 5% of asymptomatic individuals, respectively [van Benten et al., 2003; García‐García et al., 2008; Jartti et al., 2008; Peltola et al., 2008]. Semi‐quantitation revealed that the quantity of rhinovirus nucleic acid copies detected in the clinical specimens is similar in both groups and thus can not explain by itself the absence of symptoms in the control group. The number of cases in the present study is limited and the data should therefore be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, similar findings showing comparable nucleic acid copy numbers in symptomatic and in asymptomatic individuals were obtained previously in Finland using quantitative RT‐PCR [Peltola et al., 2008].

Previous studies have already attempted to assess the significance of viruses identified by PCR in asymptomatic subjects [Graat et al., 2003; van Benten et al., 2003; García‐García et al., 2008; Jartti et al., 2008; Peltola et al., 2008]. The use of sensitive PCR techniques has obviously increased virus detection rates and not only in symptomatic but also in asymptomatic subjects, and has made the interpretation of positive test results somehow more complicated. The link of causality between virus identification and symptoms remains uncertain, especially when low copy numbers and multiple viruses are detected. Furthermore, at the time of specimen collection, the patient could be in an incubation period and not experiencing any symptoms. In addition, a subject could be asymptomatic whereas the PCR detects remnants of distant infection. For instance, HBoV and HRhV may persist several weeks in nasopharyngeal cavities in convalescent patients [Jartti et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2010]. Nevertheless, some limitations have to be taken into account for this study since the number of enrolled individuals is limited, especially in the asymptomatic group.

CONCLUSION

This is the first study testing patients with influenza‐like illness for most respiratory viruses in Cambodia. The objective of the project was to describe the pattern of respiratory virus circulation during the dry season when such viruses are expected to circulate at low levels. Rhinoviruses, coronaviruses and PIVs are the more common viruses detected in patients as well as in asymptomatic persons. Several studies have been conducted previously to evaluate the viral etiologies of acute respiratory infections, but unfortunately few have compared results from symptomatic patients with those from asymptomatic individuals. This study raises the question of the significance of the detection of some respiratory viruses, especially when using highly sensitive detection methods, and of the link between the virus presence and the origin of the illness.

The data should now be completed by conducting an analysis of specimens collected during consecutive rainy seasons in order to ascertain the seasonal variation and to provide a better understanding of the epidemiology and spectrum of illness caused by respiratory viruses in tropical countries like Cambodia.

Authors declare no financial or other conflict of interest that might be construed to influence the contents of the manuscript, including the results or interpretation of publication.

Acknowledgements

Wei Wang is a recipient of a fellowship allocated by AREVA. We thank the staff of the virology unit for their technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Aguillar JC, Pérez‐Breña MP, Garcia ML, Erdman DD, Echevarria JE. 2000. Detection and identification of human parainfluenza viruses 1, 2 3, 4 in clinical samples of pediatric patients by multiplex reverse transcription‐PCR. J Clin Microbiol 38: 1191–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung‐Lindell A, Andersson B. 2005. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 12891–12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arden KE, McErlean P, Nissen MD, Sloots TP, Mackay IM. 2006. Frequent detection of human rhinoviruses, paramyxoviruses, coronaviruses, and bocavirus during acute respiratory tract infections. J Med Virol 78: 1232–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avellon AP, Perez JC, Aguillar R, Lejarazu R, Echevarria JE. 2001. Rapid and sensitive diagnosis of human adenovirus infections by a generic polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods 92: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellau‐Pujol S, Vabret A, Legrand L, Dina J, Gouarin S, Petitjean‐Lecherbonnier J, Pozzetto B, Ginevra C, Freymuth F. 2005. Development of three multiplex RT‐PCR assays for the detection of 12 respiratory RNA viruses. J Virol Methods 126: 53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas I, Avellon A, Mosquera M, Jabado O, Echevarria JE, Campos RH, Rewers M, Perez‐Breña P, Lipkin WI, Palacios G. 2005. Molecular identification of adenoviruses in clinical samples by analyzing a partial hexon genomic region. J Clin Microbiol 43: 6176–6182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SS, Chan KH, Chu KW, Kwan SW, Guan Y, Poon LL, Peiris JS. 2005. Human coronavirus NL63 infection and other coronavirus infections in children hospitalized with acute respiratory disease in Hong Kong, China. Clin Infect Dis 40: 1721–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi EH, Lee HJ, Kim SJ, Eun BW, Kim NH, Lee JA, Lee JH, Song EK, Kim SH. 2006. Ten‐year analysis of adenovirus type 7 molecular epidemiology in Korea, 1995–2004: Implication of fiber diversity. J Clin Virol 35: 388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JY, Han TH, Kim CK, Kim SW. 2006. Bocavirus infection in hospitalized children, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis 12: 1254–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JY, Han TH, Kim SW, Kim CK, Hwang ES. 2007. Detection of viruses identified recently in children with acute wheezing. J Med Virol 79: 1238–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coiras MT, Aguilar JC, García ML, Casas I, Pérez‐Breña P. 2004. Simultaneous detection of fourteen respiratory viruses in clinical specimens by two multiplex reverse transcription nested‐PCR assays. J Med Virol 72: 484–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PL, McIntosh K, Chanock RM. 1996. Respiratory syncytial virus. Virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott‐Raven. pp 1313–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, Rabenau H, Panning M, Kolesnikova L, Fouchier RA, Berger A, Burguière AM, Cinatl J, Eickmann M, Escriou N, Grywna K, Kramme S, Manuguerra JC, Muller S, Rickerts V, Stürmer M, Vieth S, Klenk HD, Osterhaus AD, Schmitz H, Doerr HW. 2003. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 348: 1967–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria JE, Erdman DD, Swierkosz EM, Holloway BP, Anderson LJ. 1998. Simultaneous detection and identification of human parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, and 3 from clinical samples by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol 36: 1388–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman DD, Weinberg GA, Edwards KM, Walker FJ, Anderson BC, Winter J, Gonzamez M, Anderson LJ. 2003. GeneScan RT‐PCR assay for detection of 6 common respiratory viruses in young children hospitalized with acute respiratory illness. J Clin Microbiol 41: 4298–4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbiani M, Terrosi C, Martorelli B, Valentini M, Bernini L, Cellesi C, Cusi MG. 2009. Epidemiological and clinical study of viral respiratory tract infections in children from Italy. J Med Virol 81: 750–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, Cox C, Walsh EE. 2005. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high‐risk adults. N Engl J Med 352: 1749–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Henrickson KJ, Savatski LL. 1998. Rapid simultaneous diagnosis of infections with respiratory syncytial viruses A and B, influenza viruses A and B, and human parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, and 3 by multiplex quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction‐enzyme hybridization assay (Hexaplex). Clin Infect Dis 26: 1397–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freymuth F, Vabret A, Cuvillon‐Nimal D, Simon S, Dina J, Legrand L, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Eckart P, Brouard J. 2006. Comparison of multiplex PCR assays and conventional techniques for the diagnostic of respiratory virus infections in children admitted to hospital with an acute respiratory illness. J Med Virol 78: 1498–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry AM, Lu X, Chittaganpitch M, Peret T, Fischer J, Dowell SF, Anderson LJ, Erdman D, Olsen SJ. 2007. Human bocavirus: A novel parvovirus epidemiologically associated with pneumonia requiring hospitalization in Thailand. J Infect Dis 195: 1038–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐García ML, Calvo C, Pozo F, Pérez‐Breña P, Quevedo S, Bracamonte T, Casas I. 2008. Human bocavirus detection in nasopharyngeal aspirates of children without clinical symptoms of respiratory infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 27: 358–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graat JM, Schouten EG, Heijnen ML, Kok FJ, Pallast EG, de Greeff SC, Dorigo‐Zetsma JW. 2003. A prospective, community‐based study on virologic assessment among elderly people with and without symptoms of acute respiratory infection. J Clin Epidemiol 56: 1218–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröndahl B, Puppe W, Hoppe A, Kühne I, Weigl JA, Schmitt HJ. 1999. Rapid identification of nine microorganisms causing acute respiratory tract infections by single‐tube multiplex reverse transcription‐PCR: Feasibility study. J Clin Microbiol 37: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jartti T, Lehtinen P, Vuorinen T, Koskenvuo M, Ruuskanen O. 2003. Predominance of rhinovirus in the nose of symptomatic and asymptomatic infants. Allergy Immunol 14: 363–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jartti T, Jartti L, Peltola V, Waris M, Ruuskanen O. 2008. Identification of respiratory viruses in asymptomatic subjects: Asymptomatic respiratory viral infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J 27: 1103–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karron RA, Froehlich JL, Bobo L, Belshe RB, Yolken RH. 1994. Rapid detection of parainfluenza virus type 3 RNA in respiratory specimens: Use of reverse transcription‐PCR‐enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol 32: 484–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieny MP, Girard MP. 2005. Human vaccine research and development: An overview. Vaccine 23: 5705–5707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König B, König W, Arnold R, Werchau H, Ihorst G, Forster J. 2004. Prospective study of human metapneumovirus infection in children less than 3 years of age. J Clin Microbiol 42: 4632–4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, Peret T, Emery S, Tong S, Urbani C, Comer JA, Lim W, Rollin PE, Dowell SF, Ling AE, Humphrey CD, Shieh WJ, Guarner J, Paddock CD, Rota P, Fields B, DeRisi J, Yang JY, Cox N, Hughes JM, LeDuc JW, Bellini WJ, Anderson LJ, SARS Working Group . 2003. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 348: 1953–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau SK, Woo PC, Yip CC, Tse H, Tsoi HW, Cheng VC, Lee P, Tang BS, Cheung CH, Lee RA, So LY, Lau YL, Chan KH, Yuen KY. 2006. Coronavirus HKU1 and other coronavirus infections in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol 44: 2063–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo LH, Tan BH, Ng LM, Tee NW, Lin RT, Sugrue RJ. 2007. Human metapneumovirus in children, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis 13: 1396–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loscertales MP, Roca A, Ventura PJ, Abacassamo F, Dos Santos F, Sitaube M, Menendez C, Greenwood BM, Saiz JC, Alonso PL. 2002. Epidemiology and clinical presentation of respiratory syncytial virus infection in a rural area of southern Mozambique. Pediatr Infect Dis J 21: 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Endo R, Ishiguro N, Ebihara T, Ishiko H, Ariga T, Kikuta H. 2006. Detection of human bocavirus in Japanese children with lower respiratory tract infections. J Clin Microbiol 44: 1132–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardy S, Ly S, Heng S, Huch C, Nora C, Asgari N, Miller M, Bergeri I, Rehmet S, Veasna D, Zhou W, Kasai T, Touch S, Buchy P. 2009. Influenza activity in Cambodia during 2006–2008. BMC Infect Dis 9: 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizgerd JP. 2006. Lung infection—A public health priority. PLoS Med 3: e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris JS, Tang WH, Chan KH, Khong PL, Guan Y, Lau YL, Chiu S. 2003. Children with respiratory disease associated with metapneumovirus in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis 9: 628–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltola V, Waris M, Osterback R, Susi P, Ruuskanen O, Hyypiä T. 2008. Rhinovirus transmission within families with children: Incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic infections. J Infect Dis 197: 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu XW, Duan ZJ, Qi ZY, Xie ZP, Gao HC, Liu WP, Huang CP, Peng FW, Zheng LS, Hou YD. 2007. Human bocavirus infection, People's Republic of China. Emerg Infect Dis 13: 165–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen C, Mulders MN, Hovi T. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis of rhinovirus isolates during successive epidemic seasons. Virus Res 85: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn BJ. 1990. The epidemiology of acute respiratory tract infection in young children: Comparison of findings from several developing countries. Rev Infect Dis 12: S870–S888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LF, Wang TL, Tang HF, Chen ZM. 2008. Viral pathogens of acute lower respiratory tract infection in China. Indian Pediatr 45: 971–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Report . 2004. Changing history. Annex Table 2: 120‐2. Geneva: World Health Organisation 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thomazelli LM, Vieira S, Leal AL, Sousa TS, Oliveira DB, Golono MA, Gillio AE, Stwien KE, Erdman DD, Durigon EL. 2007. Surveillance of eight respiratory viruses in clinical samples of pediatric patients in southeast Brazil. J Pediatr (Rio J) 83: 422–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsolia MN, Psarras S, Bossios A, Audi H, Paldanius M, Gourgiotis D, Kallergi K, Kafetzis DA, Constantopoulos A, Papadopoulos NG. 2004. Etiology of community‐acquired pneumonia in hospitalized school‐age children: Evidence for high prevalence of viral infections. Clin Infect Dis 39: 681–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabret A, Mouthon F, Mourez T, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Freymuth F. 2001. Direct diagnosis of human respiratory coronaviruses 229E and OC43 by the polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods 97: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabret A, Mourez Th, Dina J, Van Der Hoek L, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Brouard J, Freymuth F. 2005. Human coronavirus NL63, France. Emerg Infect Dis J 11: 1225–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabret A, Dina J, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Tripey V, Brouard J, Freymuth F. 2008. Human (non‐severe acute respiratory syndrome) coronavirus infections in hospitalised children in France. J Paediatr Child Health 44: 176–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Benten I, Koopman L, Niesters B, Hop W, van Middelkoop B, de Waal L, van Drunen K, Osterhaus A, Neijens H, Fokkens W. 2003. Predominance of rhinovirus in the nose of symptomatic and asymptomatic infants. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 14: 363–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoogen BG, de Jong JC, Groen J, Kuiken T, de Groot R, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD. 2001. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med 7: 719–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoek L, Pyrc K, Jebbink MF, Vermeulen‐Oost W, Berkhout RJ, Wolthers KC, Wertheim‐van dillen PM, Kaandorp J, Spaargaren J, Berkhout B. 2004. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med 10: 368–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Wang W, Yan H, Ren P, Zhang J, Shen J, Deubel V. 2010. Correlation between bocavirus infection and humoral response, and co‐infection with other respiratory viruses in children with acute respiratory infection. J Clin Virol 47: 148–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber MW, Mulholland EK, Greenwood BM. 1998. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in tropical and developing countries. Trop Med Int Health 3: 268–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg GA, Erdman DD, Edwards KM, Hall CB, Walker FJ, Griffin MR, Schwartz B. 2004. Superiority of reverse‐transcription polymerase chain reaction to conventional viral culture in the diagnosis of actute respiratory tract infections in children. J Infect Dis 15: 706–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2008. A practical guide to harmonizing virological and epidemiological influenza surveillance. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. [Google Scholar]

- Woo PC, Lau SK, Chu CM, Chan KH, Tsoi HW, Huang Y, Wong BH, Poon RW, Cai JJ, Luk WK, Poon LL, Wong SS, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Yuen KY. 2005. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol 79: 884–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SJ, Kuak EY, Shin BM. 2007. Detection of 12 respiratory viruses with two‐set multiplex reverse transcriptase‐PCR assay using a dual priming oligonucleotide system. Korean J Lab Med 27: 420–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WD, Evans DH. 1991. Detection and identification of human influenza viruses by the polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods 33: 165–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]