Abstract

Influenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) detection with short turn‐around‐time (TAT) is pivotal for rapid decisions regarding treatment and infection control. However, negative rapid testing results may come from poor assay sensitivity or from influenza‐like illnesses caused by other community‐acquired respiratory viruses (CARVs). We prospectively compared the performance of Cobas Liat Influenza A/B and RSV assay (LIAT) with our routine multiplexNAT‐1 (xTAG Respiratory Pathogen Panel; Luminex) and multiplexNAT‐2 (ePlex‐RPP; GenMark Diagnostics) using 194 consecutive nasopharyngeal swabs from patients with influenza‐like illness during winter 2017/2018. Discordant results were reanalyzed by specific in‐house quantitative nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT). LIAT was positive for influenza virus‐A, ‐B, and RSV in 18 (9.3%), 13 (6.7%), and 55 (28.4%) samples, and negative in 108 samples. Other CARVs were detected by multiplexNAT in 66 (34.0%) samples. Concordant results for influenza and RSV were seen in 190 (97.9%), discordant results in 4 (2.1%), which showed low‐level RSV (<40 000 copies/mL). Sensitivity and specificity of LIAT for influenza‐A, ‐B, and RSV were 100%, 100% and 100%, and 100%, 99.5% and 100%, respectively. The average TAT of LIAT was 20 minutes compared to 6 hours and 2 hours for the multiplexNAT‐1 and ‐2, respectively. Thus, LIAT demonstrated excellent sensitivity and specificity for influenza and RSV, which together with the simple sample processing and short TAT renders this assay suitable for near‐patient testing.

Keywords: influenza virus, nucleic acid amplification testing, point‐of‐care test, respiratory syncytial virus, turn‐around time

-

‐

Cobas Liat is highly sensitive and specific for Influenza and RSV in 86/194 children

-

‐

Other CARVs were detected by multiplex NAT in 66/196 children

-

‐

Simple processing and TAT of 20 min suitable for near‐patient testing

-

‐

LIAT assay shows excellent sensitivity and specificity for influenza and RSV

-

‐

Simple sample processing and short turn‐around‐time of 20 min render the assay suitable for near‐patient testing

-

‐

Barcode reading and direct transfer of results into the laboratory information system

1. INTRODUCTION

Influenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) detection with short turn‐around‐time (TAT) is pivotal for rapid decisions regarding treatment and infection control.1, 2 Current diagnostics for the detection of influenza virus and RSV include direct antigen detection (DAD), virus isolation by cell culture (VIC), and nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT). DAD is rapid, but had been shown to be of limited sensitivity compared to VIC.3, 4 In the past, VIC has been the gold standard for sensitive and specific identification of community‐acquired respiratory viruses (CARVs) including influenza viruse and RSV. However, VIC requires skilled technicians, dedicated cell culture equipments, and a TAT of several days, which limits the use of this technique to specialized laboratories.5 By contrast, NAT has the advantage of a shorter TAT of approximately 6 to 8 hours, and the detection of multiple pathogens by parallel testing in a semiquantitative format and as multiplexNAT. More recently, NAT platforms became available for detecting influenza viruse as point‐of‐care tests (POCTs).3, 6, 7 Besides short TAT of less than 2 hours, cartridge‐based POCTs are simple to operate, which permit their use in near‐patient settings without extensive laboratory training. However, negative results are difficult to interpret since POCT may have a limited sensitivity or the influenza‐like illnesses in question may be due to other CARVs not covered by the POCT. For this reason, comparison with a multiplexNAT assay is of considerable advantage.3 In fact, a number of centres are exploring deep‐sequencing to detect other CARVs.8 The Cobas Liat Influenza A/B and RSV real‐time assay (LIAT) is of interest, since both influenza virus‐A, ‐B as well as the RSV‐A and ‐B are targeted, all of which cause significant morbidity in younger children and older adults during the cold season, and can therefore guide initial decisions regarding antiviral therapy as well as infection control measures.9, 10, 11, 12

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

In a first phase, eight external quality assurance samples covering influenza virus‐A, ‐B, and RSV were tested by the LIAT and by our in‐house tests.4, 13 Then, the limit of detection was estimated by using twofold serial dilutions in virus transport medium (VTM) of patient samples that had tested positive for either influenza or RSV in our in‐house quantitative nucleic acid amplification (QNAT) assays.4, 13

For a prospective parallel study, 194 consecutive nasopharyngeal swabs had been submitted for routine testing between November 2017 and January 2018. The swabs were compared using the LIAT and two Food and Drug Administration (FDA)‐cleared multiplexNATs. Discordant results between the LIAT and the multiplexNATs were resolved by in‐house real‐time QNAT. Briefly, nasopharyngeal samples were collected using Copan swabs for adults or for infants and submersed in 2 mL VTM. For the LIAT, 200 µL of respiratory specimen was transferred into the single‐use, disposable assay tube using a sterile transfer pipette. The tube was capped and directly inserted into the LIAT analyzer.

For multiplexNAT‐1, the FDA‐cleared xTAG Respiratory Pathogen Panel (RPP) assay was used (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K152386; Luminex Molecular Diagnostics Inc, MV‐Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands), total nucleic acids were extracted from 200 µL of 150 respiratory specimens on the MagNa‐Pure‐96 using the Viral NA Small Volume Kit (Roche Diagnostics AG, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The nucleic acids were collected in 100 µL elution buffer and 25 µL were used for multiplexNAT‐1 according to the manufacturer's instructions. The multiplexNAT‐1 covers 22 targets consisting of adenovirus, coronavirus (229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43), human bocavirus, human metapneumovirus, human rhinovirus/enterovirus, influenza‐A, influenza‐A H1, influenza‐A H1‐2009, influenza‐A H3, influenza‐B, parainfluenza 1 to 4, RSV‐A, RSV‐B, C. pneumoniae, L. pneumophila, and M. pneumoniae.14

For multiplexNAT‐2 (ePlex‐RPP; GenMark Diagnostics, Carlsbad, CA), 200 µL of 44 respiratory samples were mixed with an equal volume of 200 µL ePlex sample buffer on a vortex for 10 seconds, and 350 µL were transferred to the RPP cartridge followed by insertion into the ePlex System. The multiplexNAT‐2 covers 23 targets consisting of adenovirus, coronavirus (229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43), human bocavirus, human metapneumovirus, human rhinovirus/enterovirus, influenza‐A, influenza‐A H1, influenza‐A H1‐2009, influenza‐A H3, influenza‐B, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, parainfluenza 1 to 4, RSV‐A, RSV‐B, B. pertussis, C. pneumoniae, L. pneumophila, and M. pneumoniae. Recently, the ePlex‐RPP has received conformité européenne (CE)‐in vitro diagnostica (IVD) and FDA clearance.15, 16

In‐house QNATs for influenza viruse and RSV were performed as previously described.3, 4, 13, 14 Briefly, after reverse transcription, influenza virus‐A was identified by amplifying specific sequences of the matrix protein M1, whereas specific hemagglutinin sequences were targeted for identifying influenza virus‐B. RSV‐A and ‐B were detected by a duplex QNAT amplifying specific sequences of the nonstructural protein 1 C. QNAT reactions were incubated at 50°C for 10 minutes and at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. The reaction mix had a total volume of 25 μL after adding 5 μL extracted nucleic acids for one‐step reverse transcription and amplification. All samples were tested in duplicates. An additional replicate was spiked with 1000 copies of the respective plasmid to detect amplification inhibition. The viral load of patient samples was determined by our in‐house QNAT. For quantification, a plasmid that contains the corresponding region of the pathogen genome is used in triplicate at 1e6, 1e4, and 1e2 copies to generate a standard curve. External quality assurance programs testing different types at different dilutions of influenza and RSV are used for validation.

Statistical analyses were performed by Prism software (version 7.0, (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA)) or GraphPad software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Two‐sided P < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

The eight external quality assurance samples correctly identified influenza virus‐A (n = 2), influenza virus‐B (n = 1), RSV‐A (n = 3), and RSV‐B (n = 2), all of which were concordant with the multiplexNAT‐1 and the intended quality assurance result. The LIAT and the multiplexNAT results were directly entered into the laboratory information system for electronic documentation and validation. The detection limit of the LIAT was evaluated using twofold serial dilutions of patient samples containing influenza virus‐A, ‐B, or RSV. For influenza virus‐A, the LIAT detected a dilution corresponding to 5000 copies/mL, for influenza virus‐B a dilution of 1250 copies/mL, and for RSV a dilution containing 2500 copies/mL.

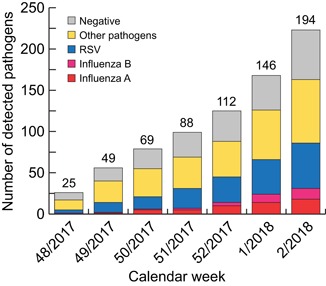

The prospective study consisted of 194 respiratory samples consecutively submitted for routine testing of 194 patients presenting with influenza‐like illness between November 2017 and January 2018 (Figure 1). The majority of patients was 16 years or younger (167; 86.1%) and approximately half of them were male (104; 53.1%). The median age of the patients was 1 year (25th percentile [Q1], 2 months; 75 th percentile [Q3], 7 years; range, 2 weeks to 87 years) (Table 1 ).

Figure 1.

Respiratory pathogen detection in nasopharyngeal swabs of 194 patients by LIAT (influenza‐A, ‐B, and RSV) and multiplexNAT (other pathogens). The columns show the cumulative number of pathogens detected from calendar week 48 in 2017 to week 2 in 2018. Above the columns, the cumulative number of tested samples is indicated. x‐Axis: time period in weeks; y‐axis: cumulative number of pathogens detected, including negative results. LIAT, Liat influenza‐A/B and RSV real‐time assay

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | Number |

|---|---|

| Patients | 194 (100%) |

| Male | 104 (53.6%) |

| Children (≤16 y) | 167 (86.1%) |

| Median (25th percentile; 75th percentile) age | 1.0 (2 mo; 7.0 y) |

| Age range | 2 wk‐87 y |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

By LIAT, 86 of 194 (44.3%) samples were positive consisting of influenza virus‐A in 18 (9.3%), influenza virus‐B in 13 (6.7%), and RSV in 55 (28.4%) cases. One hundred fifty of 194 samples were analyzed by multiplexNAT‐1 and the remaining 44 by multiplexNAT‐2. The combined multiplexNAT assays identified 18 of 194 (9.3%) influenza virus‐A, 12 of 194 (6.2%) influenza virus‐B, and 52 of 194 RSV (26.8%) positive specimens (Table 2 ). RSV‐A was identified in 29 (55.8%) cases, whereas RSV‐B in 23 (44.2%) samples. Thus, concordant results were obtained in 190 cases; discordant results for four samples consisting of RSV detected in three cases and confirmed by QNAT with 6000, 30 800, and 34 600 copies/mL, respectively. The fourth discordant sample reported influenza virus‐B by LIAT, but was negative in the influenza‐specific QNAT.

Table 2.

Performance of Cobas Liat real‐time PCR assay

| Pathogens | TP | FP | TN | FN | Total a | Sensitivity (95% CI) b | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | κ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza‐A | 18 | 0 | 176 | 0 | 194 | 100 (81.5‐100) | 100 (97.9‐100) | 100 (81.5‐100) | 100 (97.9‐100) | 1.0 |

| Influenza‐B | 12 | 1 | 181 | 0 | 194 | 100 (73.5‐100) | 99.5 (97.0‐100) | 92.3 (64.0‐99.8) | 100 (98.0‐100) | 0.96 |

| RSV | 55 | 0 | 139 | 0 | 194 | 100 (91.9‐100) | 100 (96.6‐100) | 100 (91.9‐100) | 100 (96.6‐100) | 1.0 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FN, false negatives; FP, false positives; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; TN, true negatives; TP, true positives; κ, interobserver agreement.

As reference method, 150 (77.3%) samples were tested by multiplexNAT‐1 and 44 (22.7%) by multiplexNAT‐2.

For calculations, both multiplexNATs were combined.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Taken together, the LIAT showed a sensitivity and specificity for influenza virus‐A of 100% and 100%, for influenza virus‐B 100% and 99.5%, and for RSV 100% and 100%, respectively. The positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and κ values (interobserver agreement) were high for all three pathogens (Table 2 ).

The multiplexNAT detected 77 additional pathogens (Figure 1), which were present either alone in 43 cases, or as coinfections in 23 cases (Table 3). Single infections included adenovirus (3), human bocavirus (4), coronaviruses (5), human metapneumovirus (6), parainfluenza viruses (6), and rhinovirus/enterovirus (19).

Table 3.

Characteristics of respiratory samples with more than one pathogen

| Age (y/m+) | Sex | 1. Pathogen | 2. Pathogen | 3./4. Pathogen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | F | Influenza‐A | Metapneumovirus | |

| 1 | M | Influenza‐A | Metapneumovirus | |

| 1 | F | Influenza‐A | Metapneumovirus | Coronavirus HKU1 rhinovirus/enterovirus |

| 1+ | M | Influenza‐A | Metapneumovirus | |

| 1 | F | RSV‐A | Coronavirus HKU1 | Rhinovirus/enterovirus |

| 1+ | M | RSV‐A | Coronavirus HKU1 | Metapneumovirus |

| 1+ | F | RSV‐A | Rhinovirus/enterovirus | |

| 1+ | F | RSV‐A | Rhinovirus/enterovirus | |

| 1+ | M | RSV‐A | Rhinovirus/enterovirus | |

| 0.5+ | M | RSV‐A | Coronavirus NL63 | Metapneumovirus |

| 2 | M | RSV‐B | Metapneumovirus | |

| 2 | M | RSV‐B | Rhinovirus/enterovirus | |

| 1 | F | RSV‐B | Bocavirus | |

| 1 | F | RSV‐B | Bocavirus | |

| 1 | F | RSV‐B | Coronavirus HKU1 | |

| 7+ | F | RSV‐B | Adenovirus | |

| 5+ | F | RSV‐B | Rhinovirus/enterovirus | |

| 5 | F | Adenovirus | Metapneumovirus | |

| 40 | M | Adenovirus | Rhinovirus/enterovirus | |

| 1 | F | Bocavirus | Metapneumovirus | |

| 0.5+ | F | Coronavirus OC43 | Rhinovirus/enterovirus | |

| 1 | M | Metapneumovirus | Rhinovirus/enterovirus | |

| 1+ | M | Metapneumovirus | Rhinovirus/enterovirus |

Abbreviation: RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

The median age of patients with single infections was 1 year (25th percentiles [Q1], 2 months; 75th percentile [Q3], 3 years) and 38 (88.4%, P = 0.804) of the 43 cases were found in children. Among the patients with single infections, 29 individuals were male (median age, 1 year, 25th percentiles [Q1], 6 months; 75th percentile [Q3], 9 years) and thus a strong trend was seen for male gender but did not reach statistical significance, P = 0.056. This observation is solely based on the demographics, and would require dedicated clinical‐diagnostic studies. However, it has been reported by others that children of male gender may be more susceptible for severe respiratory disease manifestations.17, 18, 19, 20

In 17 of 23 (73.9%) coinfections, RSV (13), and influenza virus‐A (4) were found together with other pathogens, but influenza virus‐B was not found in coinfections (Table 3 ). Median age of the patients with coinfections was 1 year (25th percentiles [Q1], 1 month; 75th percentile [Q3], 2 years) and 22 (95.7%, P = 0.21) of 23 coinfections were detected in pediatric patients. For both single and coinfections, median age of the patients was 1 year, but Q1 and Q3 were lower in coinfections.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of the prospective evaluation of the LIAT during the winter season 2017/2018 (Figure 1) indicate excellent sensitivity and specificity for detection of influenza viruse and RSV when compared to routine diagnostic multiplexNAT. The LIAT showed a sensitivity of 100% for all three pathogens. The specificity reached 100% for influenza virus‐A, 99.5% for influenza virus‐B, and 100% for RSV when compared with multiplexNAT and QNAT. Only four discordant results were encountered, which concerned RSV in three cases and influenza virus‐B in one case among 194 samples (Table 2). For the influenza virus‐B case, the sample was negative by multiplexNAT‐1 and tested twice negative by in‐house QNAT.13 Repeat testing by LIAT was not possible due to lack of sample material.

For the RSV cases, the LIAT scored three samples positive that tested negative by multiplexNAT (multiplexNAT‐1: two samples, multiplexNAT‐2: one sample). These discordant results were resolved by our in‐house QNAT with viral loads of 6000, 30 800, and 34 600 copies/mL of VTM, respectively. This suggested a limited sensitivity of the multiplexNAT possibly due to multiplexing or target sequence issues.21 The detection of 6000 copies/mL of VTM by QNAT in one LIAT RSV‐positive sample is in line with the results from our where 5000 copies/mL of VTM of RSV were detectable. The sensitivities for influenza virus‐A (2500 copies/mL of VTM) and influenza virus‐B (1250 copies /mL of VTM) were in a similar range, thereby permitting detection of acutely ill patients having typically much higher viral loads.4, 13

In previous studies, the LIAT was compared to other commercial NAT.6, 7, 22, 23 The results of these studies suggest that LIAT has superior sensitivity compared to other POCT. However, the samples were mostly obtained from adult patients, which is now complemented by our study, where the majority was symptomatic children (Table 1).

From week 52 in 2017 to week 2 in 2018, influenza virus‐A and ‐B cocirculated among our predominatly pediatric population (Figure 1), whereas mostly influenza virus‐B dominated among adults during January and Feburary 2018.24 In Switzerland, influenza is a reportable disease and epidemiological evaluation is performed by the Sentinella surveillance network that is based on weekly notifications by physicians and the mandatory reporting of influenza subtypes by diagnostic laboratories.

The LIAT generated a valid result in 194 of 195 (99.5%) samples. In our laboratory, the LIAT was easy to handle including inexperienced personnel and features like barcode reading and direct transfer of the results into the laboratory information system saved time and eliminated error‐prone manual procedures. A hands‐on time of less than 5 minutes plus an assay time of 15 minutes resulted in a TAT of 20 minutes that can be reached even for personal with minimal training. Thus, the LIAT permits rapid responses including decisions regarding antiviral therapy for influenza as well as to cohort patients as part of infection control in institution settings including outpatient clinics, emergency rooms, and intensive care units.

The following limitations should be noted. First, batch testing of patient samples is not possible and at the peak season of influenza and RSV, the sequential testing may result in the loss of the TAT advantage (3 samples per hour, 24 per 8 hours, 72 per 24 hours). However, it can be partly compensated for by direct and parallel testing on more than one LIAT instrument. Second, LIAT lacks the identification of influenza virus‐A subtypes. Detection of influenza virus‐A subtypes may influence isolation procedures in hospital settings. In addition, in immunocompromised patients may be at risk for dual infections, which is rare and usually one pathogen is dominant. In such cases, subsequent multiplexNAT or QNAT provide semiquantitative results that are helpful to identify the main driver of the infection. Because the LIAT is easy to handle, the testing system may be attractive for being used by personnel not trained as professional laboratory analysts. However, in our practice, a qualification program with corresponding documentation and requalification every 1 or 2 years need to be performed in accordance with laboratory regulations, and not only when failing internal and external quality assurance programs.

In conclusion, the LIAT can reduce the TAT compared to conventional multiplexNAT or QNAT. In this study, the sensitivity of the LIAT seemed to be equivalent or slightly increased over current multiplexNAT and comparable to specific QNAT. The specificity was similar to the multiplexNAT. Thus, LIAT seems useful for rapid testing and management decisions regarding infection control and therapy, and could be followed by QNAT to document viral replication and clearance if needed, and/or by multiplexNAT to detect other respiratory pathogens.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the members of the Division Infection Diagnostics for dedicated technical assistance, and Professors Ulrich Heininger, MD, and Urs Frey, MD, and the team at the University Children's Hospital Basel for the excellent collaboration. The manufacturer of the LIAT (Roche, Rothkreuz, Switzerland) provided two instruments and the used tests free of charge

Gosert R, Naegele K, Hirsch HH. Comparing the Cobas Liat Influenza A/B and respiratory syncytial virus assay with multiplex nucleic acid testing. J Med Virol. 2019;91:582–587. 10.1002/jmv.25344

References

REFERENCES

- 1. Falsey AR, Murata Y, Walsh EE. Impact of rapid diagnosis on management of adults hospitalized with influenza. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:354‐360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hirsch HH, Martino R, Ward KN, Boeckh M, Einsele H, Ljungman P. Fourth european conference on infections in leukaemia (ECIL‐4): guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of human respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, and coronavirus. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:258‐266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beckmann C, Hirsch HH. Diagnostic performance of near‐patient testing for influenza. J Clin Virol. 2015;67:43‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khanna N, Widmer AF, Decker M, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in patients with hematological diseases: single‐center study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:402‐412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liao RS, Tomalty LL, Majury A, Zoutman DE. Comparison of viral isolation and multiplex real‐time reverse transcription‐PCR for confirmation of respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus detection by antigen immunoassays. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:527‐532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nolte FS, Gauld L, Barrett SB. Direct Comparison of Alere i and Cobas Liat Influenza A and B tests for rapid detection of influenza virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:2763‐2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Melchers WJG, Kuijpers J, Sickler JJ, Rahamat‐Langendoen J. Lab‐in‐a‐tube: real‐time molecular point‐of‐care diagnostics for influenza A and B using the Cobas(R) Liat(R) system. J Med Virol. 2017;89:1382‐1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hirsch HH. Spatio‐temporal virus surveillance for severe acute respiratory infections in resource‐limited Settings: how deep need we go? Clin Infect Dis. 2018, 10.1093/cid/ciy663 PMID:30099498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neuzil KM, Mellen BG, Wright PF, Mitchel EF, Jr , Griffin MR. The effect of influenza on hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and courses of antibiotics in children. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:225‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. El Saleeby CM, Bush AJ, Harrison LM, Aitken JA, Devincenzo JP. Respiratory syncytial virus load, viral dynamics, and disease severity in previously healthy naturally infected children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:996‐1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:179‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee N, Lui GCY, Wong KT, et al. High morbidity and mortality in adults hospitalized for respiratory syncytial virus infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1069‐1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khanna N, Steffen I, Studt JD, et al. Outcome of influenza infections in outpatients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11:100‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beckmann C, Hirsch HH. Comparing luminex NxTAG‐Respiratory Pathogen Panel and RespiFinder‐22 for multiplex detection of respiratory pathogens. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1319‐1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Babady NE, England MR, Jurcic Smith KL, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the ePlex Respiratory Pathogen Panel for the detection of viral and bacterial respiratory tract pathogens in nasopharyngeal swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nijhuis RHT, Guerendiain D, Claas ECJ, Templeton KE. Comparison of ePlex Respiratory Pathogen Panel with laboratory‐developed real‐time PCR assays for detection of respiratory pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:1938‐1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muenchhoff M, Goulder PJR. Sex differences in pediatric infectious diseases. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(suppl 3):S120‐S126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1545‐1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lu CY, Huang LM, Fan TY, Cheng AL, Chang LY. Incidence of respiratory viral infections and associated factors among children attending a public kindergarten in Taipei City. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117:132‐140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Souza Costa VH, Baurakiades E, Viola Azevedo ML, et al. Immunohistochemistry analysis of pulmonary infiltrates in necropsy samples of children with non‐pandemic lethal respiratory infections (RSV; ADV; PIV1; PIV2; PIV3; FLU A; FLU B). J Clin Virol. 2014;61:211‐215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu A, Colella M, Tam JS, Rappaport R, Cheng SM. Simultaneous detection, subgrouping, and quantitation of respiratory syncytial virus A and B by real‐time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:149‐154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen L, Tian Y, Chen S, Liesenfeld O. Performance of the cobas((R)) influenza A/B assay for rapid pcr‐based detection of influenza compared to prodesse ProFlu + and viral culture. Eur J Microbiol Immunol. 2015;5:236‐245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibson J, Schechter‐Perkins EM, Mitchell P, et al. Multi‐center evaluation of the cobas(R) Liat(R) influenza A/B & RSV assay for rapid point of care diagnosis. J Clin Virol. 2017;95:5‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) . Influenza in Europe, Weekly Influenza Update. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); 2018. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control at https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/seasonal-influenza-annual-epidemiological-report-2017-18-season [Google Scholar]