Abstract

Molecular techniques increased the number of documented respiratory infections. In a substantial number of cases the causative agent remains undetected. Since August 2014, an increase in Enterovirus(EV)‐D68 infections was reported. We aimed to investigate epidemiology and clinical relevance of EV‐D68. From June to December 2014 and from September to December 2015, 803 and 847 respiratory specimens, respectively, were tested for respiratory viruses with a multiplex RT‐PCR. This multiplex RT‐PCR does not detect EV‐D68. Therefore, 457 (2014) and 343 (2015) specimens with negative results were submitted to an EV‐specific‐RT‐PCR. EV‐positive specimens were tested with an EV‐D68‐specific‐RT‐PCR and genotyped. Eleven specimens of 2014 tested positive in the EV‐specific‐RT‐PCR and of these seven were positive in the EV‐D68‐specific‐RT‐PCR. Typing confirmed these as EV‐D68. Median age of EV‐D68‐positive patients was 3 years (1 month‐91 years). Common symptoms included fever (n = 6, 86%), respiratory distress (n = 5, 71%), and cough (n = 4, 57%). All EV‐D68‐positive patients were admitted to hospital, 4 (57%) were admitted to intensive care units and 6 (86%) received oxygen. One patient suffered from acute flaccid paralysis. Seven specimens of 2015 were positive in the EV‐specific‐RT‐PCR but negative in the EV‐D68‐specific‐RT‐PCR. In conclusion, use of an EV‐specific‐RT‐PCR allowed us to detect EV‐D68 circulation in autumn 2014 that was not detected by the multiplex RT‐PCR and was associated with severe disease.

Keywords: acute flaccid paralysis, human enterovirus 68, myelitis, respiratory tract infection, sequencing

Abbreviations

- ARTI

acute respiratory tract infection

- EV

enterovirus

- HRV

human rhinovirus

- ICU

intensive care unit

- Min

minutes

- RT‐PCR

reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction

- S

seconds

- TCID

Tissue culture infective dose

- VP

viral protein

1. INTRODUCTION

Molecular techniques, namely multiplex reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reactions (RT‐PCRs) for respiratory viruses, have increased the number of Acute Respiratory Tract Infections (ARTIs) in which the causative agent is identified.1 However, in a substantial number of cases the causative agent is not detected.

The Enterovirus genus of the Picornaviridae family consists of small non‐enveloped RNA viruses classified in nine enterovirus species and three human rhinovirus (HRV) species (Virus Taxonomy: 2014 Release, http://www.ictvonline.org/virusTaxonomy.asp). Enteroviruses (EV) and HRV are recognized as leading causes of ARTIs in humans. As such, they are included in multiplex RT‐PCRs for respiratory viruses. It is unknown whether these assays detect all types of EV with reasonable sensitivity. Importantly, EV‐D68 is not detected by all diagnostic assays for the detection of EV or respiratory viruses with good sensitivity or might be misidentified as HRV.2

Circulation of EV‐D68 has been reported since 1962 and has been associated with sporadic cases of respiratory disease and small outbreaks.3 Since August 2014, an increase in infections caused by EV‐D68 has been reported in the USA, Canada, and in Europe.4, 5, 6

The study aimed to assess the performance of EV‐D68 detection of the commercial multiplex RT‐PCR for respiratory viruses used routinely in our laboratory, to investigate whether EV‐D68 circulated in Northern France in the autumns of 2014 and 2015, and to describe the clinical characteristics of EV‐D68 infections.

2. METHODS

2.1. Respiratory samples

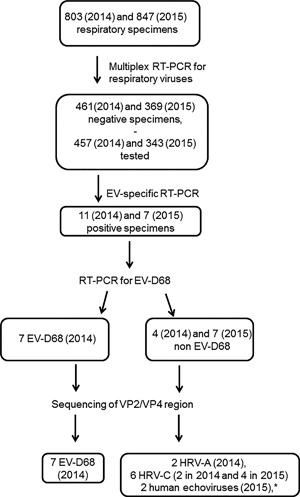

From June 1 till December 31, 2014, 803 respiratory specimens (371 nasopharyngeal swabs, 194 nasopharyngeal aspirations, 213 bronchoalveolar lavages, 6 sputa, 6 bronchial aspirations, 6 pleural fluids, 3 pulmonary biopsies, and 4 specimens of unspecified nature) from 615 patients were sent to our laboratory for respiratory virus detection. From September 7 till December 31, 2015, 847 respiratory specimens (382 nasopharyngeal swabs, 295 nasopharyngeal aspirations, 163 bronchoalveolar lavages, 3 sputa, 2 tracheal secretions, and 2 specimens of unspecified nature) from 674 patients were sent to our laboratory for respiratory virus detection. These specimens were analyzed by using a commercial multiplex RT‐PCR (Anyplex II RV16 Detection kit [Seegene, Seoul, Korea]). A total of 461/803 (57.4%) and 369/847 (43.6%) specimens tested negative. Of these negative specimens 457/461 (in 2014) and 343/369 (in 2015) had RNA extracts available and were submitted to an EV‐specific‐RT‐PCR.7 EV positive specimens were then submitted to a EV‐D68‐specific RT‐PCR8 and to molecular typing (see below) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for patients and specimens included in the study. EV: enterovirus. *one specimen was untypeable

2.2. Virus isolate

EV‐D68 reference strain Fermon was provided by the National Reference Laboratory for EV, Clermont‐Ferrand, France, and cultured on MRC‐5 cells. RNA from 200 μL of supernatant containing 3.16 × 106 TCID50/mL9, 10 was extracted by using the Magtration System 12GC with the MagDEA® Viral DNA/RNA 200 (GC) kit (Precision System Science Europe GmbH, Mainz, Germany) with elution volume of 100 μL according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.3. Respiratory virus detection

Respiratory specimens were stored at −80°C before RNA extraction. RNA was extracted from 200 μL of respiratory specimens as described above for the virus isolate. An aliquot of RNA was stored at −80°C.

RNA extracts were tested with the kit Anyplex II RV16 Detection kit (Seegene) to be screened for a panel of respiratory viruses including influenza virus A and B, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) A and B, human adenovirus (HAdV), human metapneumovirus, coronaviruses 229E, NL63, and OC43, parainfluenza virus 1‐4, HRV A/B/C, human enterovirus, and bocavirus 1‐4.

2.4. EV and EV‐D68 screening

Specimens that yielded negative results with the multiplex RT‐PCR were tested with an in‐house EV‐specific real‐time RT‐PCR targeting the 5′ non coding region by using primers and probe from Verstrepen et al.7 Briefly, reverse transcription was performed in a total volume of 20 μL with the Omniscript RT Kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France), with 1× Buffer, 1 µM antisens primer, 0.5 mM dNTP, 10 units of RNAse Inhibitor, 4 units of Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase and RNAse‐free water. A total of 5 μL of extracted RNA was added and reactions were run on a GeneAmp PCR System 2700 (Applied Biosystems, France) thermocycler with the following cycling profile: 45 min at 37°C and 5 min at 90°C. Real‐time PCR was performed in a total volume of 20 μL with the LightCycler Faststart DNA Master HybProbe Kit (Roche, Applied Science, Meylan France), with 1× Mastermix, 5 mM magnesium chloride, 600 nM of sens (CCCTGAATGCGGCTAATC), and antisens primers (ATTGTCACCATAAGCAGCCA), 100 nM probe (FAM‐AACCGACTACTTTGGGTGTCCGTGTTT‐TAMRA), 0.5 U of Uracyl‐DNA Glycosylase, and RNAse‐free water. A total of 5 μL of cDNA was added and reactions were run on a LightCycler 480 Real‐Time PCR Instrument (Roche) with the following profile: 10 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, 45 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, and 45 s at 60°C.

EV positive specimens were submitted to a EV‐D68‐specific real‐time RT‐PCR.8 RT‐PCR was performed as described in8 with the exception that Fast Virus 1‐Step Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used and primer and probe concentrations were 600 nM for forward and reverse primer, and 100 nM for the probes. Reactions were run on a 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with the following profile: 15 min at 50°C, 2 min at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 15 s at 50°C, and 45 s at 60°C.

2.5. Molecular typing and phylogenetic analysis

EV positive specimens were typed by partial amplification and sequencing of the viral protein (VP) 4/VP2 and/or VP1 regions. The VP4/2 region was amplified by using the primers described by Wisdom et al.11 Briefly, reverse transcription and amplification was performed by using the SuperScript III One‐Step RT‐PCR System with Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, France). The mix contained 7.5 μL H2O, 25 μL 2× Reaction Mix, 37.5 pmol of primers VP4 OS and VP4 OAS, 2 μL of RT/Platinum Taq Mix, and 8 μL of extraced nucleic acids. The RT‐PCR was performed with the following profile: 30 min at 45°C, 2 min at 94°C followed by 4 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 46°C, and 1 min 30 s at 68°C, followed by 36 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 53°C, and 1 min 30 s at 68°C with a final extension for 7 min at 68°C. Nested PCR was performed by using Amplitaq DNA Polymerase with Buffer I (Applied Biosystems). A total of 5 μL of the RT‐PCR product were added to a mix containing 5 μL of buffer I, 2 μL dNTP, 1 μL Amplitaq DNA Polymerase, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 28.5 μL H2O, 37.5 pmol of primers VP4 IS and VP4 IAS. Reactions were run with the following profile: 5 min at 94°C followed by 4 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 46°C, and 1 min 30 s at 72°C, followed by 34 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 53°C, and 1 min 30 s at 72°C with a final extension for 10 min at 72°C. The VP1 region was amplified by using the technique described by Nix et al.12 Briefly, reverse transcription was performed by using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Thermofisher Scientific, Courtaboeuf, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR and nested PCR were performed as described12 except that 5 μL of the product of the first PCR was added to the second PCR. PCR reactions were performed on a GeneAmp PCR System 2700 (Applied Biosystems) thermocycler. PCR products were sequenced directly.

Sequences were assembled and aligned to EV‐D68 or HRV genome with SeqScape Software v2.7 (Applied Biosystems). Consensus sequences were submitted to the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) by using the blastn algorithm.

Additionally, sequences were aligned and phylogenetic trees were constructed with Mega‐Software (MEGA 613) and the neighbor‐joining method with maximum composite likelihood model and pairwise deletions. Bootstrapping was performed with 1000 replicates and values above 70% are shown at the nodes.

2.6. Patients and clinical characteristics

Demographic and clinical data (symptoms, hospitalization, oxygen requirement, intensive care unit [ICU] stay and outcome) of patients in whom EV‐D68 was detected were retrospectively collected from medical records. Need for hospitalization, oxygen requirement, and admission to ICU were used as indicators of severity of infection.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM, United States). Frequencies were expressed as numbers and percentage and quantitative variables as median and range.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Respiratory virus detection

A total of 342/803 (43%) specimens of 2014 yielded a positive result and 461/803 (57%) specimens of 2014 yielded a negative result in the commercial multiplex RT‐PCR for respiratory viruses. A total of 474/847 (56%) specimens of 2015 tested positive, 4/847 (0.5%) specimens gave invalid results, and 369/847 (43.5%) specimens tested negative in the commercial multiplex RT‐PCR for respiratory viruses, respectively. The viruses detected are detailed in the supplementary Table S1.

3.2. Detection of EV‐D68 by different molecular assays

In order to investigate whether the commercial multiplex RT‐PCR for respiratory viruses used in our laboratory detected EV‐D68, RNA extracted from the EV‐D68 Fermon strain culture supernatant was subjected to this assay and yielded a negative result. Consequently, we assumed that we might have missed EV‐D68 infections during the reported period of circulation in summer and autumn 2014.

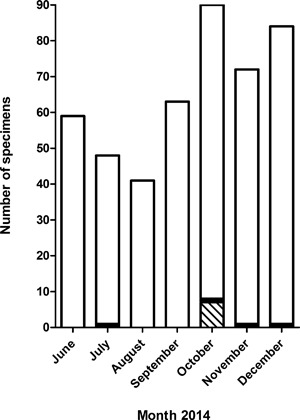

We retrospectively tested with our EV‐specific‐RT‐PCR assay the 457 respiratory specimens that were sent to our laboratory between June and December 2014 and prospectively the 343 respiratory specimens that were sent to our laboratory between September and December 2015 and that had yielded negative results in the multiplex RT‐PCR (Fig.1). We found 11 (2014) and 7 (2015) specimens that gave positive results with cycle thresholds (Cts) ranging from 24.6 to 36.8 (Table 1). EV‐D68 RNA was detected in seven of these with the EV‐D68‐specific assay (Table 1). All EV‐D68 positive specimens clustered in October 2014 (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Results of RT‐PCRs and molecular typing of EV‐positive specimens

| Specimen (year) | EV‐specific‐RT‐PCR (Ct) | EV‐D68‐specific RT‐PCR (Ct) | Typing of VP2/VP4 region (nearest type) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (2014) | POSITIVE (33.9) | NEGATIVE | HRV‐A45 |

| 2 (2014) | POSITIVE (36.0) | POSITIVE (40.1) | EV‐D68 |

| 3 (2014) | POSITIVE (27.9) | POSITIVE (29.7) | EV‐D68 |

| 4 (2014) | POSITIVE (35.2) | POSITIVE (38.4) | EV‐D68 |

| 5 (2014) | POSITIVE (33.9) | POSITIVE (37.4) | EV‐D68 |

| 6 (2014) | POSITIVE (36.3) | POSITIVE (40.0) | EV‐D68 |

| 7 (2014) | POSITIVE (29.0) | POSITIVE (31.5) | EV‐D68 |

| 8 (2014) | POSITIVE (24.6) | POSITIVE (28.2) | EV‐D68 |

| 9 (2014) | POSITIVE (31.2) | NEGATIVE | HRV‐C33 |

| 10 (2014) | POSITIVE (33.1) | NEGATIVE | HRV‐A59 |

| 11 (2014) | POSITIVE (34.1) | NEGATIVE | HRV‐C37 |

| 12 (2015) | POSITIVE (32.7) | NEGATIVE | HRV‐C9 a |

| 13 (2015) | POSITIVE (36.8) | NEGATIVE | HRV‐C9 a |

| 14 (2015) | POSITIVE (29.5) | NEGATIVE | Human Echovirus 6 |

| 15 (2015) | POSITIVE (29.5) | NEGATIVE | HRV‐C9 a |

| 16 (2015) | POSITIVE (32.3) | NEGATIVE | Untypeable |

| 17 (2015) | POSITIVE (31.0) | NEGATIVE | HRV‐C9 a |

| 18 (2015) | POSITIVE (31.7) | NEGATIVE | Human Echovirus 9 b |

HRV, Human rhinovirus; EV, enterovirus; VP, viral protein; Ct, cycle threshold.

Sequence identity to the reference sequence (GQ223228) was 76%.

Sequence identity to the closest sequence in BLAST was 85%.

Figure 2.

Seasonal distribution of EV‐D68 and HRV positive specimens. The histogram represents the number of specimens tested in the EV‐specific‐RT‐PCR and that gave positive (black and hatched bars) or negative results (white bars). The result of molecular typing of the positive specimens is indicated (HRV, black bars; EV‐D68, hatched bars)

3.3. Phylogenetic analysis

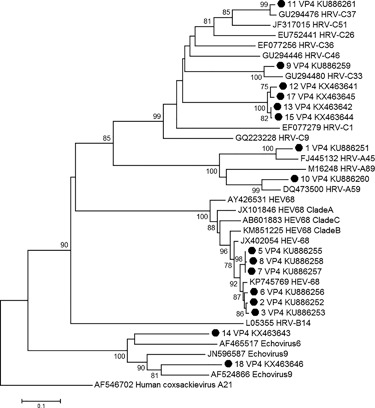

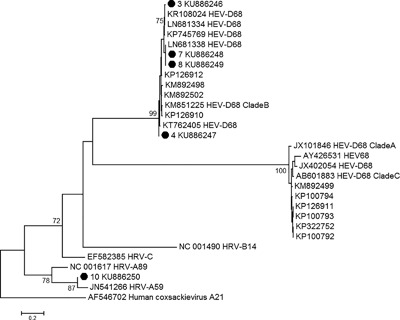

Typing was achieved by partial VP4/VP2 and/or VP1 sequencing for 18 and 6 samples, respectively. The identification of EV‐D68 was confirmed for all EV‐D68‐specific RT‐PCR positive samples. Among the 11 remaining samples, 8 were identified as rhinoviruses and 2 as echoviruses, and typing was unsuccessful in one specimen (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 region showed that all typeable EV‐D68 specimens belonged to clade B (Fig. 4) which was the predominant clade in Europe in 2014.5, 6 The VP1 sequences of the studied strains displayed close genetic relationships with the VP1 sequences of strains circulating in the Auvergne region of France in October and November 2014 (LN681334, LN681338), in Denmark in October 2014 (KR108024), and in HongKong (KT762405) in March 2014 (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the partial VP2/VP4 region of Enterovirus strains detected in this study. A neighbor‐joining tree of VP2/VP4 sequences was constructed by using MEGA6. Coxsackievirus A21 was used as outgroup. Sequences from this study are indicated with a black circle and numbered as in Table 1. The percentage of bootstraps (out of 1000) that supports the corresponding clade is shown if higher than 70%. HRV‐A, ‐B, and ‐C, Coxsackievirus A21, human echoviruses E6 and E9, and several EV‐D68 reference sequences were included. The sequence that could be obtained for the specimen of patient 4 was significantly shorter and therefore not included in the phylogenetic analysis

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the partial VP1 region of Enterovirus strains detected in this study. A neighbor‐joining tree of partial VP1 sequences was constructed by using MEGA6. Coxsackievirus A21 was used as outgroup. Sequences from this study are indicated with a black circle and numbered as in Table 1. The percentage of bootstraps (out of 1000) that supports the corresponding clade is shown if higher than 70%. HRV‐A, ‐B and, ‐C, Coxsackievirus A21 and several EV‐D68 reference sequences were included. The sequence that could be obtained for the specimen of patient 2 was significantly shorter and therefore, not included in the phylogenetic analysis

3.4. Clinical manifestations of EV‐D68 infections

Characteristics of EV‐D68 positive patients are shown in Table 2. Five patients were female (71%) and median age was 3 years (range: 1 month to 91 years). Common symptoms included fever (n = 6, 86%), acute respiratory distress (n = 5, 71%), and cough (n = 4, 57%). Less common symptoms were rhinitis (n = 2, 29%), wheezing (n = 2, 29%), and paralysis (n = 1, 14%). All patients were admitted to hospital, 4 (57%) were admitted to ICUs, and 6 (86%) received oxygen. One patient presented with acute flaccid paralysis. She was a 3‐year‐old girl who had an episode of acute gastroenteritis. Six days later, she was admitted to hospital with fever, rhinopharyngitis, and acute flaccid paralysis of the left leg. Cerebrospinal fluid showed pleiocytosis (165 leucocytes/mm3) with normal protein and glucose levels. Acute respiratory distress and paraplegia occurred 2 days afterward. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed myelitis. Spontaneous mobility of the superior limbs and the right inferior limb had recovered at 1 year follow‐up. However, the patient still suffered from chronic respiratory insufficiency necessitating mechanical ventilation at follow‐up after 19 months.

Table 2.

Characteristics of EV‐D68 positive patients

| Patient number | Gender | Age (years) | Fever | Rhinitis | Cough | Pneumopathy | Acute respiratory distress | Asthma | Paralysis | Polyradiculonevritis | Hospitalisation | Oxygen requirement | ICU (days) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | F | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 147 | Respiratory insufficiency, tetraplegia |

| 3 | F | 24 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Favorable |

| 4 | M | 53 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Favorable |

| 5 | F | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Favorable |

| 6 | F | 91 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Favorable |

| 7 | F | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Favorable |

| 8 | M | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 10 | Atelectasis, myopathia |

4. DISCUSSION

This study revealed that 18 specimens, initially tested negative with a multiplex RT‐PCR for respiratory viruses (of a total of 1650 specimens tested), were positive for specific EV genome detection. Among them, seven were EV‐D68‐positive, eight were HRV‐positive, and two were identified as echoviruses. The existence of a high number of HRV and EV types with considerable genomic variability represents a challenge for diagnostic assays and it is conceivable that any diagnostic assay will not be able to detect all HRV and EV types with the same sensitivity. Importantly, EV‐D68 is not detected at all by this multiplex RT‐PCR for respiratory viruses because even undiluted supernatant of an EV‐D68 Fermon strain culture with a TCID50/mL of 3.16 × 106 yielded negative results (data not shown). This confirms the findings of a recent publication.5 We therefore, changed our diagnostic algorithm to include testing of specimens that yield negative results in the multiplex RT‐PCR for respiratory viruses in our EV‐specific RT‐PCR. This approach may delay the diagnosis of EV‐D68 infections and thus the detection of an outbreak of respiratory infections associated with this emergent type. There is clearly a need for evaluation and update of commercial multiplex RT‐PCR assays for respiratory viruses to include the detection and the identification of EV‐D68.

All EV‐D68 positive specimens were collected in October 2014 (weeks 40 to 43) (Fig. 2) coinciding with the peak of EV‐D68 detection in Europe and France.5, 6 Phylogenetic analysis revealed a close genetic relationship with EV‐D68 strains that circulated in the Auvergne region of France during the same time period (LN681334, LN681338) (Fig. 4).

The severity of infections in our study appeared higher than reported in Europe during the same time period, because in our study 57% of EV‐D68 positive patients were admitted to ICUs versus 11% in a European study and a French study.5, 6 However, it cannot be excluded that the higher severity we found in this study is due to the fact that testing for respiratory viruses was prescribed preferentially in more severe cases and less severe cases therefore stayed undiagnosed.

EV‐D68 is mostly associated with respiratory diseases but recent reports raised the question of its role in acute neurological illnesses in the USA.14, 15, 16 Three cases of acute flaccid paralysis associated with EV‐D68 infection were reported in Europe in 2014.5, 17 Here, we described the second case of acute flaccid paralysis associated with EV‐D68 detection in a respiratory sample in France.17 As previously observed in the cases described in the US and in Europe the genome of EV‐D68 was only detected in the respiratory tract.14, 15, 16, 17 The cerebrospinal fluid specimen of the patient was retrospectively tested with a EV‐specific RT‐PCR and was negative for EV genome detection. However, the CSF and a blood specimen tested positive for Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV) with a viral load of 2300 copies/mL in the blood. In the cases of acute neurological illnesses described recently only one case had EV‐D68 detected in blood, whereas EV‐D68 was typically detected in respiratory specimens. Nevertheless, the authors concluded on a possible causal association of EV‐D68 with myelitis.14, 15, 16, 17 Therefore, the findings in our case do not contradict the association of EV‐D68 with myelitis. However, taking into account the weakly positive EBV PCR in the cerebrospinal fluid, the myelitis might also be due to EBV infection.

In conclusion, the use of an EV‐specific‐RT‐PCR allowed us to detect the circulation of EV‐D68 in Northern France in autumn 2014 that had not been detected by the commercial multiplex RT‐PCR. Although few EV‐D68 cases were detected, the diagnosis of EV‐D68 was of clinical relevance because EV‐D68 was associated with severe disease.

5. ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Supporting Table S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the technicians of the virology department for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, Université Lille 2 (Equipe d'accueil 3610), and Centre Hospitalier Régional et Universitaire de Lille. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, data collection, and analysis nor in writing of the report.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

Engelmann I, Fatoux M, Lazrek M, et al. Enterovirus D68 detection in respiratory specimens: Association with severe disease. J Med Virol. 2017; 89:1201–1207. 10.1002/jmv.24772

REFERENCES

- 1. Gharabaghi F, Hawan A, Drews SJ, Richardson SE. Evaluation of multiple commercial molecular and conventional diagnostic assays for the detection of respiratory viruses in children. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011; 17:1900–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jaramillo‐Gutierrez G, Benschop KS, Claas EC, et al. September through October 2010 multi‐centre study in the Netherlands examining laboratory ability to detect enterovirus 68, an emerging respiratory pathogen. J Virol Methods. 2013; 190:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holm‐Hansen CC, Midgley SE, Fischer TK. Global emergence of enterovirus D68: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016. 5:64–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Midgley CM, Jackson MA, Selvarangan R, et al. Severe respiratory illness associated with enterovirus D68—Missouri and Illinois, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014; 63:798–799. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poelman R, Schuffenecker I, Van Leer‐Buter C, Josset L, Niesters HG, Lina B. European surveillance for enterovirus D68 during the emerging North‐American outbreak in 2014. J Clin Virol. 2015b; 71:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schuffenecker I, Mirand A, Josset L, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients infected with enterovirus D68, France, July to December 2014. Euro Surveill. 2016; 21:19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Verstrepen WA, Kuhn S, Kockx MM, Van De Vyvere ME, Mertens AH. Rapid detection of enterovirus RNA in cerebrospinal fluid specimens with a novel single‐tube real‐time reverse transcription‐PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2001; 39:4093–4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Poelman R, Scholvinck EH, Borger R, Niesters HG, van Leer‐Buter C. The emergence of enterovirus D68 in a Dutch University Medical Center and the necessity for routinely screening for respiratory viruses. J Clin Virol. 2015a; 62:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spearman C. The method of right and wrong cases (constant stimuli) without Gauss formulae. Br J Psychol. 1908; 2:227–242. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karber G. Beitrag zur kollektivcn behandlung pharmakologischer reihenver‐suche. Arch Exp Path Pharmak. 1931; 162:480–487. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wisdom A, Leitch EC, Gaunt E, Harvala H, Simmonds P. Screening respiratory samples for detection of human rhinoviruses (HRVs) and enteroviruses: comprehensive VP4‐VP2 typing reveals high incidence and genetic diversity of HRV species C. J Clin Microbiol. 2009; 47:3958–3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nix WA, Oberste MS, Pallansch MA. Sensitive, seminested PCR amplification of VP1 sequences for direct identification of all enterovirus serotypes from original clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2006; 44:2698–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013; 30:2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pastula DM, Aliabadi N, Haynes AK, et al. Acute neurologic illness of unknown etiology in children—Colorado, August–September 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014; 63:901–902. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Greninger AL, Naccache SN, Messacar K, et al. A novel outbreak enterovirus D68 strain associated with acute flaccid myelitis cases in the USA (2012‐14): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015; 15:671–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Messacar K, Schreiner TL, Maloney JA, et al. A cluster of acute flaccid paralysis and cranial nerve dysfunction temporally associated with an outbreak of enterovirus D68 in children in Colorado, USA. Lancet. 2015; 385:1662–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lang M, Mirand A, Savy N, et al. Acute flaccid paralysis following enterovirus D68 associated pneumonia, France, 2014. Euro Surveill. 2014; 19:44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Supporting Table S1.