Abstract

Aminopeptidase N (E.C. 3.4.11.2) is a membrane‐bound metalloproteinase expressed in many tissues. Although its cytoplasmic portion has only eight amino acids, cross‐linking of CD13 by monoclonal antibodies (mAb) has been shown to trigger intracellular signaling. A functional association between CD13 and receptors for immunoglobulin G (FcγRs) has been proposed. In this work, we evaluated possible functional interactions between CD13 and FcγRs in human peripheral blood monocytes and in U‐937 promonocytic cells. Our results show that during FcγR‐mediated phagocytosis, CD13 redistributes to the phagocytic cup and is internalized into the phagosomes. Moreover, modified erythrocytes that interact with the monocytic cell membrane through FcγRI and CD13 are ingested simultaneously, more efficiently than those that interact through the FcγRI only. Also, co‐cross‐linking of CD13 with FcγRI by specific mAbs increases the level and duration of Syk phosphorylation induced by FcγRI cross‐linking. Finally, FcγRI and CD13 colocalize in zones of cellular polarization and coredistribute after aggregation of either of them. These results demonstrate that CD13 and FcγRI can functionally interact on the monocytic cell membrane and suggest that CD13 may act as a signal regulator of FcγR function.

Keywords: Fc receptors, macrophages, phagocytosis

INTRODUCTION

Receptors for the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G (IgG; FcγRs) are glycoproteins that belong to the family of multichain immune recognition receptors (MIRRs) and are expressed on the vast majority of leukocytes. Three distinct types of classic FcγRs have been described: one with high‐affinity for FcγRI and two low‐affinity receptors, FcγRII and FcγRIII [ 1 , 2 ]. Cross‐linking of FcγRs by IgG‐opsonized particles or IgG‐containing immunocomplexes triggers an intracellular cascade of biochemical events that leads to a variety of important cellular functions such as phagocytosis, immune regulation, cytolysis, and transcriptional activation of cytokine‐encoding genes, which initiate inflammatory responses related to protection against bacterial infection, autoimmunity, and hypersensitivity [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ].

Cell activation mediated by other MIRRs, such as the B cell receptor (BCR) and the T cell receptor (TCR), is modulated by costimulatory and inhibitory molecules [ 8 ]. Similarly, several studies suggest that signaling induced by activatory FcγRs is susceptible to modulation by other membrane proteins (signal regulators) such as tetraspanins, signal regulatory proteins, and siglecs (sialic acid‐binding lectins) [ 9 ], although the biological significance of these phenomena has not been explored in detail.

CD13 (aminopeptidase N) is an ectoenzyme (E.C.3.4.11.2) of the superfamily of zinc metalloproteases [ 10 ] expressed in many tissues including kidney, intestine, liver, placenta, and the nervous system [ 11 ]. In the hematopoietic system, CD13 is expressed on stem cells and during most developmental stages of myeloid cells [ 12 ], and for this reason, it is widely used as a marker of myelomonocytic cells in the diagnosis of hematopoietic malignant disorders. Furthermore, CD13 participates in angiogenesis regulation [ 13 ], cellular motility, and dendritic cell (DC)‐induced T cell activation [ 14 ]. CD13 is also a receptor for human coronavirus 229E and other enteropathogenic coronaviruses [ 15 ] and participates in human cytomegalovirus infection [ 16 , 17 ]. Moreover, the possibility of CD13 being a receptor for the coronavirus responsible for the severe acute respiratory syndrome has been suggested recently [ 18 ]. Because of its ectopeptidase activity, CD13 has been implicated in the regulation of vasoactive peptides, neuropeptide hormones, and immunomodulating peptides such as interleukin‐6 and ‐8 (IL‐6 and IL‐8, respectively) [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ].

A role for CD13 as a signal‐transducing molecule in monocytes has been reported [ 23 , 24 ], although it has a short cytosolic domain of eight amino acid residues containing no known signaling motifs [ 25 ]. This observation has led to the suggestion that signal transduction by CD13 requires the participation of an auxiliary membrane protein of still‐unknown identity.

Cooperation between CD13 and FcγRs was first suggested when McIntyre et al. [ 24 ] in 1989 proposed that the Ca++ increase induced by anti‐CD13 monoclonal antibodies (mAb) in the human monocytic cell line U‐937 could result from mAb‐induced formation of membrane complexes between the antigen (CD13) and the FcγRs. The involvement of FcγRs in CD13‐mediated signaling was deduced from two observations: the effect could not be reproduced using F(ab)′2 fragments of the antibody, and the magnitude of this effect varied according to the isotype of the anti‐CD13 antibody tested [ 24 ]. However, the conclusion that CD13 signals through FcγRs has been challenged by the observation that inhibition of the enzymatic activity of CD13, which in principle would not alter the formation of the CD13‐FcγR complexes, blocks the CD13‐mediated signal, although other reports showed that enzymatic activity is not required for CD13‐mediated signaling [ 26 , 27 ].

In 1996, Tokuda and Levy [ 28 ] found a correlation between CD13 expression and phagocytosis of carboxyl microspheres. They noticed that the most actively phagocytic cells in the monocytic gate of peripheral blood mononuclear cells expressed higher levels of CD13 (more than twice the level) than less phagocytic cells. Moreover, they showed that induction of differentiation of these cells with 1,25‐dyhydroxyvitamin D3, which increases the phagocytic capacity of monocytes, diminishes CD13 expression in cells with low, but not in those with high, phagocytic capacity, suggesting a role for CD13 in phagocytosis [ 28 ].

In this work, we evaluated the possible functional association between FcγRs and CD13 using several approaches. Our results lead us to propose CD13 as a signal regulator of FcγRI‐mediated signal transduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and antibodies

The promonocytic cell line U‐937 [obtained from the American Type Cell Culture Collection (ATCC), Rockville, MD] was cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 1 mM sodium pyruvate 0.1 mM MEM nonessential amino acid solution, 0.1 mM L‐glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C with 5% CO2. Murine monoclonal anti‐human FcγRI (32.2) was purified from supernatants of the corresponding hybridoma obtained from the ATCC and was conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) by standard procedures. Murine monoclonal anti‐human CD13 (clone 452, IgG1) was purified in our laboratory from the culture supernatant of the hybridoma, kindly donated by Dr. Meenhard Herlyn (Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology, Philadelphia, PA). F(ab)′2 fragments of the antibodies were prepared with immobilized ficin (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Texas Red®‐X succinimidyl ester (TR) was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Monoclonal anti‐human CD13 (clone WM47, IgG1) was from Sigma Chemical Co. Monoclonal anti‐human CD82 was from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Monoclonal anti‐human CD33 (P67.6) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (CA). Antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (PY20 and PY99) and polyclonal anti‐Syk (N‐19) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse monoclonal dinitrophenyl (DNP)‐specific antibody 3B5 (IgG2b), used as opsonizing antibody in the confocal microscopy phagocytosis assay, was purified from culture supernatant of the correspondent hybridoma and conjugated with FITC. Goat anti‐mouse IgG‐FITC, goat anti‐mouse IgG‐horseradish peroxidase (HRP), streptavidin‐TR, and biotinylated F(ab)′2 fragments of goat anti‐mouse IgG were from Zymed (San Francisco, CA). F(ab)′2 fragments of goat anti‐mouse IgG and F(ab)′2 fragments of goat anti‐mouse IgG conjugated with TR were from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA).

Human peripheral blood monocytes and monocyte‐derived macrophages

Normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation of buffy coats from healthy donors using Ficoll‐Paque Plus (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden), as described previously [ 29 ], washed four times, and cultured for 45 min at 37°C in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 5% autologous plasma‐derived serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM MEM nonessential amino acid solution, 0.1 mM L‐glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, allowing monocytes to adhere to plastic. Nonadherent cells were eliminated by several washes, and adherent cells enriched for monocytes (more than 95% purity as determined by flow cytometry using CD14 and CD33 as markers of the monocytic population) were cultured for 48 h in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C with 5% CO2 and finally harvested by mechanical scraping for further experimentation. Monocyte‐derived macrophages were obtained after culturing adherent cells for 6 days in the presence of 5% autologous plasma‐derived serum as described [ 29 , 30 ].

Phagocytosis by laser‐scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM)

Sheep red blood cells (SRBC) were washed in 2.5% dextrose, 0.05% gelatin, 2.5 mM veronal, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.15 mM CaCl2 (DGVB2+) and sensitized with 2,4,6‐trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid sodium salt in borate buffer (boric acid 200 mM, NaCl 150 mM, pH 8.5) for 10 min at room temperature (RT) and then washed twice with DGVB2+ and once with serum‐free RPMI medium. Opsonization of SRBC was achieved by incubation of a suspension of sensitized SRBC with a subhemagglutinating concentration of anti‐DNP‐FITC‐labeled 3B5 mAb (IgG2b) or anti‐DNP‐nonlabeled 4F8 mAb (IgG2b) for 60 min at RT. Unbound antibodies were removed by washing. For the phagocytosis assay, the opsonized fluorescent erythrocytes were incubated for different times at 37°C with monocytes or U‐937 cells in supplemented RPMI medium in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Simultaneously, monocytes or U‐937 cells were incubated with nonopsonized erythrocytes or erythrocytes opsonized with nonfluorescent IgG under the same conditions. The cells were then washed with ice‐cold phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and where indicated, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min, incubated on ice with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb, pelleted, and mounted on microscopy slides [mounting medium 50% PBS/glycerol v/v, 0.1% 1,4‐diazabicyclo (2.2.2) octane (DABCO)] for analysis on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. In other samples, biotinylated F(ab)′2 fragments of the anti‐CD13 antibody were added and incubated for 30 min. After two more washes, TR‐conjugated streptavidin (TR‐streptavidin, Zymed) was added to the cell suspension for 20 min, and cells were pelleted and mounted as above. X‐Y slices of every image were generated. Only an appropriate X‐Y slice of each image is presented. Where indicated, noninternalized erythrocytes were lysed by hypotonic shock before CD13 staining. Incubation with streptavidin‐TR alone led to negligible staining.

CD13/FcγRI‐specific phagocytosis

Modified SRBC were prepared as described previously [ 31 ] with some modifications. Briefly, erythrocytes (at 1×109/ml in 0.1 M carbonate buffer, pH 8.6) were incubated with 125 μg/ml sulfosuccinimidobiotin (Pierce) for 20 min at 4°C. Next, they were coated with streptavidin (125 μg/ml, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 30 min at 4°C. The biotin‐streptavidin‐coated erythrocytes were washed and incubated with biotinylated F(ab)′2 fragments of goat anti‐mouse IgG (Zymed) for 30 min [SRBCs coated with biotin, streptavidin, and F(ab)′2 fragments of biotinylated anti‐IgG antibodies (EBS‐Ab)].

For the phagocytosis assay, monocytes, monocyte‐derived macrophages, or U‐937 cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of complete or F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐FcγRI mAb, anti‐CD13 mAb, or both, washed, and mixed with erythrocytes at a ratio of one monocytic cell:25–50 EBS‐Ab at 37°C for 20–30 min in the case of peripheral blood monocytes and for 90 min with U‐937 cells. Finally, after lysis of noninternalized erythrocytes by hypotonic shock, phagocytosis was quantified by light microscopy. Data are expressed as phagocytic indexes (the number of ingested erythrocytes/100 phagocytic cells). Statistical analysis was performed using a paired t‐test with a significance level of 0.05.

Cell stimulation and immunoblotting

Cell suspensions (3×106 cells/300 μl) were incubated for 10 min on ice in serum‐free RPMI 1640 with primary antibodies (10 μg each anti‐FcγRI, anti‐FcγRI and anti‐CD13, or anti‐CD13 alone). After a brief centrifugation at 1000 r.p.m., the supernatant was discarded, the cells were resuspended in fresh serum‐free medium, and 20 μg F(ab)′2 fragments of secondary antibody were added for the indicated periods of time at 37°C. Stimulation was stopped by placing tubes on ice and adding 150 μl ice‐cold Tris‐buffered saline (TBS; 10 mM Tris‐HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5). The cells were pelleted by a brief centrifugation, resuspended in ice‐cold lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris‐HCl, glycerol 5%, Triton X‐100 1%, pH 7.5) with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mM NaF, and 1 μg/ml each aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin A, and Na3VO4, and kept on ice for 15 min. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 r.p.m. at 4°C for 15 min. Protein quantification was made using the DC protein assay (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA). Aliquots of the lysates were boiled in Laemmli sample buffer, separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE), and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio‐Rad) using a semi‐dry Trans‐blot apparatus (Bio‐Rad). Membranes were blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 overnight at 4°C. After washing, tyrosine phosphorylated proteins were detected with a mixture of two antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (PY20 and PY99) in 3% BSA and a secondary HRP‐conjugated antibody. Chemiluminiscent signal was detected using Super Signal enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce), according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a Fluor‐S Multi‐imager (Bio‐Rad). Densitometry was performed using the Quantity One software (Bio‐Rad). Membranes were stripped with 0.1 M glycine (pH 2.5), blocked for 1 h, and reblotted with anti‐Syk antibody, followed by HRP‐conjugated secondary antibody. Detection was made as described above.

Colocalization and coredistribution assays by LSCM

For colocalization studies, peripheral blood monocytes or U‐937 cells (2.5×105/300 μl) were fixed in 1% PFA for 20 min on ice, washed, and subsequently incubated on ice for 15 min in PBS with 5% fetal calf serum and 0.1% sodium azide. F(ab)′2 fragments of primary antibody (anti‐FcγRI) were added (10 μg) for 30 min at 4°C. The cells were washed and then incubated with F(ab)′2 fragments of a secondary FITC‐labeled antibody (1:300 dilution) for 30 min at 4°C. After washing, biotinylated F(ab)′2 fragments of the anti‐CD13 mAb were added for 30 min on ice and detected with streptavidin‐TR for 30 min at 4°C. Finally, cells were washed and mounted in PBS/glycerol/DABCO as described above for analysis by LSCM. In other experiments, TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb were used.

For coredistribution experiments, monocytes or U‐937 cells were incubated with anti‐FcγRI mAb for 30 min at 4°C. After washing, they were incubated with F(ab)′2 fragments of a secondary FITC‐labeled antibody for 20 min at 4°C and then at 37°C for different periods of time to allow the receptor’s aggregation. After washing and fixing in 1% PFA for 20 min on ice, CD13 was detected as above in the presence of 0.1% sodium azide, and cells were mounted for analysis by LSCM. The opposite experiment was conducted, inducing aggregation of CD13 with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of the 452 mAb, followed by F(ab)′2 fragments of a secondary, nonlabeled antibody. After cell fixation at 4°C, FcγRI was detected with FITC‐labeled, anti‐FcγRI mAb.

RESULTS

CD13 redistributes to the zones of FcγR‐mediated phagocytosis and is internalized into the phagosomes

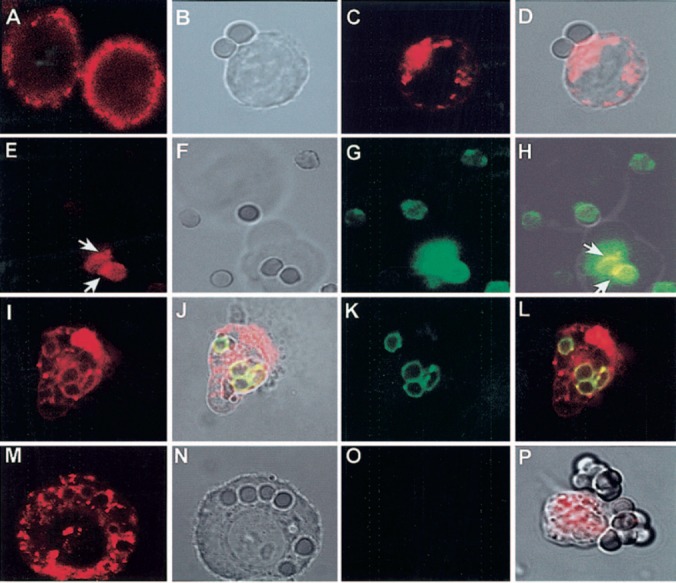

Changes in the cellular distribution of CD13 associated with FcγR‐mediated phagocytosis were evaluated by confocal microscopy. Peripheral blood monocytes or U‐937 cells were incubated with erythrocytes opsonized with FITC‐labeled IgG for different periods of time. These opsonized erythrocytes aggregate both types of FcγRs expressed on the monocytic cell membrane (i.e., FcγRI and FcγRII). To visualize CD13 at different stages of the process, we stopped phagocytosis by transferring the assay tubes into ice or fixing cells with 1% PFA at 4°C. At this temperature, they were incubated with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb for 30 min or alternatively, with biotinylated F(ab)′2 fragments of the antibody and subsequently, with TR‐streptavidin. Figure 1A shows distribution of CD13 on the U‐937 cell membrane before phagocytosis. After 60 min of incubation at 37°C, a clear redistribution of CD13 to the zones of contact with opsonized erythrocytes was seen (Fig. 1B, 1C, 1D). In the initial steps of phagocytosis (Fig. 1E, 1F, 1G, 1H), CD13 was concentrated in the zones of the membrane starting to internalize the erythrocytes (Fig. 1E, white arrows), seen in yellow in the projection (Fig. 1H). Green fluorescence outside of the two visible erythrocytes (Fig. 1G, and 1H) corresponds to other erythocytes barely visible at this plane of slicing. Figure 1H corresponds to a single projection obtained by rotating the data of the original image around the x‐axis. In this image, it is evident that colocalization of FcγRI and CD13 is restricted to the zones of contact between the membranes of erythrocytes and that of the U‐937 cell.

Figure 1.

CD13 redistributes to the phagocytic cup during FcγR‐mediated phagocytosis in U‐937 cells. (A) CD13 distribution on resting cells. (B–D) U‐937 cells were incubated with IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes for 60 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed, and CD13 was detected by incubation with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of mAb anti‐CD13. (D) Redistributed CD13 in the zone of contact with erythrocytes. (E–H) U‐937 cells were incubated with FITC‐IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes for 60 min at 37°C. Cells were chilled, and CD13 was detected by incubation with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of mAb anti‐CD13. CD13 is visualized in the zones of the membrane in contact with erythrocytes (E, white arrows). Cell membranes are out of focus (see transmitted light, F), impeding detection of distribution of the rest of the population of CD13 molecules in this slice. Erythrocytes are fluorescent in the green channel (G). (H) Projection shows in yellow sites of colocalization of FcγR (IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes) and CD13 (arrows). (I–L) U‐937 cells were incubated with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb at 4°C before phagocytosis, washed, and incubated with FITC‐IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes for 90 min at 37°C. Noninternalized erythrocytes were lysed before observation in the confocal microscope. Erythrocytes internalized into phagosomes (J, K) are surrounded by CD13 (I). (J and L) Colocalization of the CD13‐red signal with FITC‐IgG‐labeled erythrocytes in the phagosomes. (M–O) Similar experiment as that shown in I–L but with erythrocytes opsonized with nonlabeled IgG. CD13 is seen inside the phagosomes (M). No fluorescence is seen in the green channel (O). (P) Transmitted light and red channel‐composed image of U‐937 cells incubated with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb before incubation with IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes for 60 min at 4°C. CD13 does not redistribute to zones of contact with erythrocytes.

Moreover, in samples in which U‐937 cells were preincubated with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of the mAb and then incubated with IgG‐FITC‐opsonized erythrocytes for longer periods of time (90 min) to allow complete internalization, phagosomes appeared entirely surrounded by CD13 (Fig. 1I, 1J, 1K, 1L). Internalization of CD13 into phagosomes was also observed when the erythrocytes were opsonized with nonfluorescent IgG (Fig. 1M, 1N, 1O), in which case, no green fluorescence was detected in the corresponding channel (Fig. 1O) under the instrument settings used to detect a bright red fluorescence, ruling out the possibility of a bleed‐through‐originated signal. In cells incubated with opsonized erythrocytes at 4°C, no redistribution of CD13 to the zones of contact was detected (Fig. 1P) .

In peripheral blood monocytes, which internalized IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes more efficiently than U‐937 cells, the same redistribution phenomenon was seen ( Fig. 2 ). As can be noted in Figure 2A, and 2B, distribution of the CD13 label in the phagosomes can be visualized as a uniform red staining or as a ring surrounding the internalized erythrocyte, depending on the plane of the X‐Y slice. Figure 2C, and 2D, shows monocytes after 30 min of incubation with IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes at 37°C, showing most of the CD13 initially expressed on the cell membrane, now internalized in the phagosomes.

Figure 2.

CD13 redistributes to the phagocytic cup during FcγR‐mediated phagocytosis in peripheral blood human monocytes. (A, B) Human monocytes were incubated with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb at 4°C before phagocytosis, washed, and incubated with IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes for 15 min at 37°C. Noninternalized erythrocytes were lysed before observation in the confocal microscope. Erythrocytes internalized in phagosomes are surrounded by CD13. Distribution of CD13 label in the phagosomes is visualized as a uniform red staining in one phagosome and as a ring surrounding the other two internalized erythrocytes as a result of the plane of the X‐Y slice. (C, D) After 30 min, phagosomes show internalized CD13.

After internalization of erythrocytes in U‐937 cells and primary monocytes, red fluorescent signals were detected in periphagosomal and perinuclear areas in the cytoplasm, as shown in Figures 1M, and 2A .

Coaggregation of FcγRI and CD13 increases the FcγRI‐mediated phagocytic capacity of monocytic cells

To analyze in detail the functional implications of CD13 redistribution during phagocytosis, we focused on the activatory, high‐affinity FcγRI, as this receptor, in contrast to FcγRII, does not have inhibitory isoforms that could obscure the effect of CD13 on FcγR‐mediated signaling. Thus, we compared the phagocytic index when SRBC, coated with biotin, streptavidin, and F(ab)′2 fragments of biotinylated anti‐IgG antibody (EBS‐Ab), bound to the monocytic or U‐937 cell through the FcγRI alone, through the FcγRI and CD13 together, or through CD13 alone.

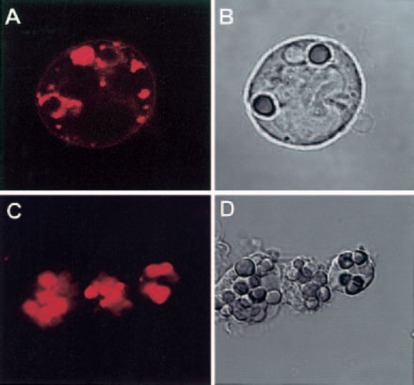

In peripheral blood monocytes and U‐937 cells, FcγRI alone was able to mediate phagocytosis of EBS‐Ab. However, when EBS‐Ab interacted with U‐937 cells through FcγRI and CD13 (10 μg each mAb), phagocytosis was 220% higher (n=6) than that mediated by FcγRI alone ( Fig. 3A ). Similar results were obtained using two different anti‐CD13 mAb—the 452 mAb and the WM47 mAb (data not shown)—and using intact antibody or its F(ab)′2 fragments. EBS‐Ab, interacting through FcγRI and CD82, which is another highly expressed molecule in U‐937 cells that has also been reported to possibly cooperate with FcγRs [ 32 ], did not induce statistically significant changes in the phagocytic index even when mAb anti‐CD82 was used as complete antibody (Fig. 3A) .

Figure 3.

Coaggregation of FcγRI with CD13 increases the phagocytic capacity of U‐937 cells and peripheral blood human monocytes. (A) U‐937 cells were incubated with 10 μg of the mAb specific for the indicated molecules for 30 min at 4°C. After washing, the cells were incubated for 90 min at 37°C with erythrocytes opsonized with F(ab)′2 fragments of biotin‐labeled goat anti‐mouse IgG (EBS‐Ab). After lysis of noninternalized erythrocytes, phagocytosis was evaluated by light microscopy. Data are presented as the number of EBS‐Ab internalized per 100 cells (Phagocytic Index). Mean ± sd of six independent experiments; c = complete mAb. (B) Peripheral blood monocytes from human donors were incubated with the indicated concentrations of anti‐FcγRI mAb with (•) or without (□) F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb (10 μg) for 30 min. After washing, incubation with EBS‐Ab was carried out at 37°C for 30 min. After lysis of noninternalized erythrocytes, the phagocytic index was determined by light microscopy. Data are the mean phagocytic index (±se) of at least four different donors for each point. (∗) Statistically significant difference comparing FcγRI + CD13 with FcγRI alone; P < 0.05. (C) Peripheral blood monocytes from different human donors were incubated with 10 μg anti‐CD13 mAb, 10 μg anti‐FcγRI, or the combination of the two antibodies and subsequently, with EBS‐Ab, as indicated above. Each distinct symbol represents a different donor. (D) Peripheral blood monocytes from different human donors were incubated with different concentrations of anti‐CD13 452 mAb and subsequently with EBS‐Ab. Data represent mean and sdof at least four donors. Solid bar represents the phagocytic index obtained with 10 μg anti‐FcγRI mAb.

In peripheral blood monocytes, EBS‐Ab that interacted through CD13 and FcγRI, were also internalized more efficiently than those that bound through FcγRI alone (Fig. 3B). At concentrations of 10 μg of each antibody, the phagocytic index was 48.41% higher than that observed with FcγRI alone (n=11). Although cells from different donors showed large differences in phagocytic capacity, it was clear that in cells from all donors examined, the effect of co‐engagement of CD13 and FcγRI was observed (Fig. 3C) .

It is surprising that anti‐CD13 mAb tested triggered EBS‐Ab internalization with a phagocytic index similar to that observed through FcγRI alone, using complete antibody or its F(ab)′2 fragments. To determine the specificity of this CD13‐mediated phagocytosis, we preincubated cells with a mAb specific for CD33, another highly expressed molecule in U‐937 cells, or with an unrelated IgG1 mAb (anti‐DNP), and both conditions resulted in phagocytic indexes not significantly different from those obtained when the cells were incubated without antibodies (Fig. 3A), although as expected, EBS‐Ab bound to cells preincubated with the anti‐CD33 mAb. Furthermore, CD13‐mediated phagocytosis of EBS‐Ab depended on the amount of anti‐CD13 mAb bound to monocytes (Fig. 3D) .

The effect of co‐engaging CD13 on FcγRI‐mediated phagocytosis was even higher in monocyte‐derived macrophages obtained after culturing blood monocytes for 6 days ( Fig. 4A ). In these cells, CD13 alone also mediates phagocytosis (Fig. 4A, and 4B, ▪). Figure 4B shows the relative phagocytic index (ratio of the phagocytic index of FcγRI‐CD13 to that of FcγRI alone at the corresponding dose of anti‐FcγRI mAb). The maximal increase (250%) was observed with 2 μg anti‐FcγRI and 10 μg F(ab)′2 fragments of the anti‐CD13 mAb compared with 2 μg of anti‐FcγRI alone.

Figure 4.

Coaggregation of FcγRI with CD13 increases the phagocytic capacity of monocyte‐derived macrophages from human donors. Cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of anti‐FcγRI mAb with or without F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb (10 μg) or with anti‐CD13 mAb alone (10 μg) for 30 min. After washing, incubation with EBS‐Ab was carried out at 37°C for 30 min. After lysis of noninternalized erythrocytes, the phagocytic index was determined by light microscopy. (A) Data represent the mean phagocytic index of cells from three different donors. (B) Data are presented as the relative phagocytic index, which corresponds to the ratio of the phagocytic index observed with the combination of the two mAb to the phagocytic index obtained with anti‐FcγRI mAb alone. The number close to each point corresponds to the fold increase attributable to CD13 co‐cross‐linking.

Co‐cross‐linking of FcγRI and CD13 prolongs Syk phosphorylation induced by FcγRI cross‐linking

Next, we characterized the effect of FcγRI and CD13 co‐cross‐linking on FcγRI‐mediated signaling. A crucial step in FcγR‐mediated signal transduction is activation of tyrosine kinase Syk. Consequently, we examined the time‐course of Syk phosphorylation induced by co‐cross‐linking of FcγRI and CD13 in U‐937 cells and compared it with that induced by cross‐linking FcγRI alone.

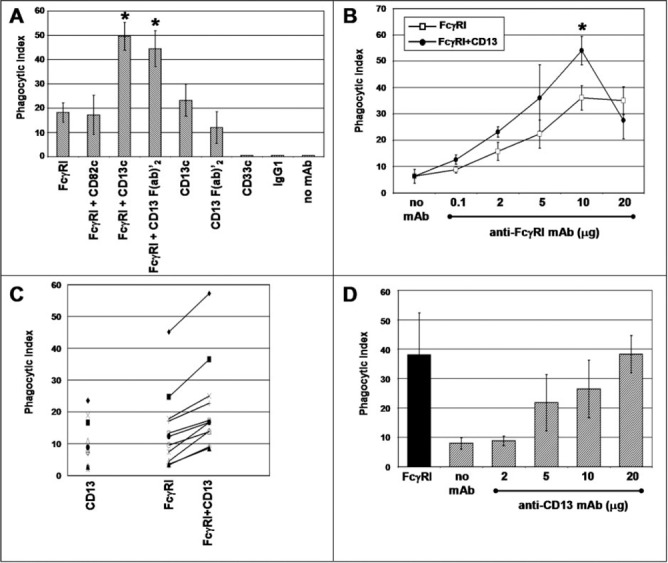

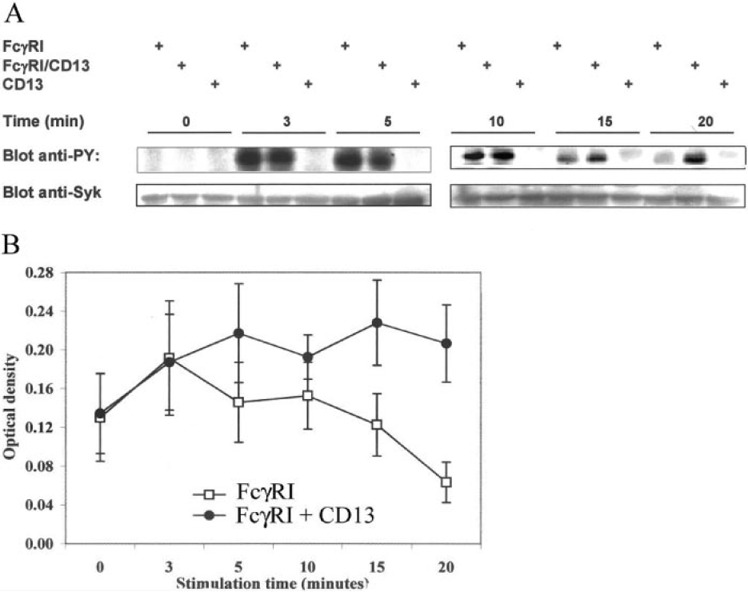

As shown in Figure 5A , and 5B , the phosphorylation peak level of Syk was observed after 3 min of stimulation through FcγRI alone. This level of phosphorylation started to decrease at 10 min. In contrast, co‐cross‐linking of FcγRI and CD13 induced an increase in the maximum level of Syk phosphorylation after 10 min and its preservation for a longer period of time (up to 20 min). CD13 cross‐linking alone was not able to induce Syk phosphorylation at any of the tested times (Fig. 5A), even using different concentrations of primary and secondary antibodies (not shown). Figure 5B shows the averages of densitometric quantification of the band corresponding to Syk in the antiphosphotyrosine immunoblots of five independent experiments similar to that shown in Figure 5A .

Figure 5.

Coaggregation of FcγRI with CD13 induces a prolongation in the Syk phosphorylation level. (A) U‐937 cells were incubated with 10 μg each of anti‐FcγRI mAb, anti‐CD13 mAb, or the combination of both antibodies. After cross‐linking for 3, 5, 10, 15, or 20 min with F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐mouse antibodies at 37°C, cells were lysed, and proteins were resolved on SDS‐PAGE. Tyrosine‐phosphorylated proteins were blotted with PY20‐PY99 antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (Blot anti‐PY). Bands in the upper panels show the phosphorylated protein in the molecular weight of Syk (72 kDa). To corroborate the identity of this band, the same membranes were stripped and reprobed with an anti‐Syk polyclonal antibody (Blot anti‐Syk). (B) Averaged data from five independent experiments as that shown in A. Each point represents the mean ± sd of the optical density of the Syk band in the anti‐PY blot.

CD13 partially colocalizes and coredistributes with FcγRI

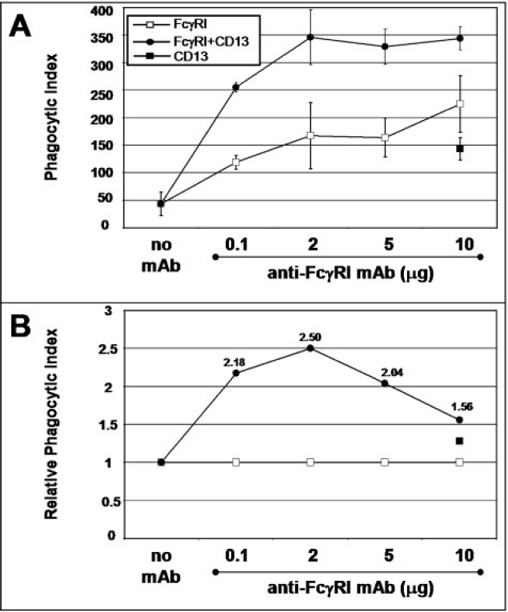

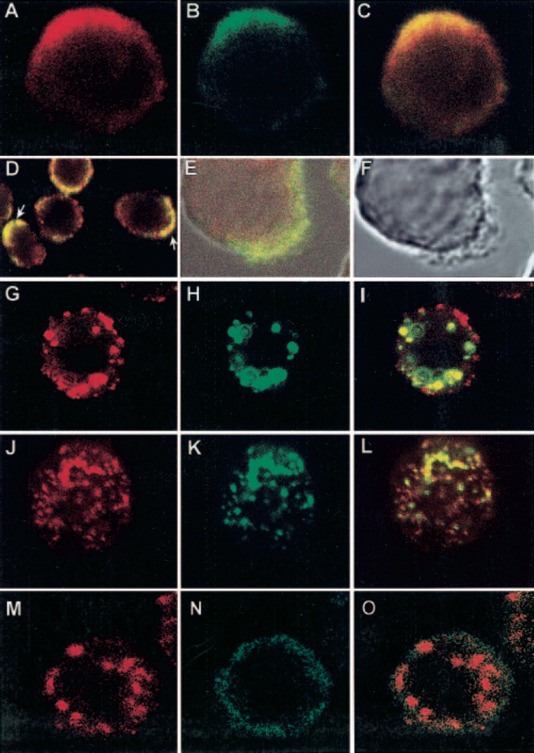

We used confocal microscopy to determine colocalization of the two molecules and coredistribution after aggregation of each of them. In resting, prefixed cells, using antibody incubation temperatures of 4°C, and in the presence of 0.1% sodium azide, there is colocalization of FcγRI and CD13 only in cells in which both molecules are polarized (∼40% of the cells; Fig. 6A , 6B , 6C , 6D ). These zones of polarization coincide with the zones of the membrane most prominently showing lamellipodia and fillopodia as shown in Figure 6E, and 6F .

Figure 6.

Colocalization and coredistribution of CD13 with FcγRI. (A–D) U‐937 cells were prefixed with PFA. FcγRI was stained first with anti‐FcγRI mAb and FITC‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of secondary antibody (B). CD13 was then stained by incubating cells with biotinylated F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb and streptavidin‐TR at 4°C (A). (C) Colocalization of FcγRI and CD13 (yellow) in a polarized cell. (D) A field showing CD13 and FcγRI polarized in several cells (arrows). (E, F) Zones of FcγRI and CD13 colocalization correspond to membrane zones showing lamellipodia and fillopodia. (G–I) U‐937 cells were incubated with anti‐FcγRI mAb followed by FITC‐labeled secondary antibody for 20 min at 4°C. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 20 min to allow aggregation, and after fixation, CD13 staining was performed with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb at 4°C in the presence of sodium azide. (I) Zones of coredistribution of FcγRI and CD13 as yellow aggregates. (J–L) U‐937 cells were incubated with TR‐labeled F(ab)′2 fragments of anti‐CD13 mAb, followed by incubation with a nonlabeled, secondary antibody for 20 min at 4°C and subsequently, at 37°C for 20 min to allow aggregation. After fixation, FcγRI was detected with FITC‐labeled anti‐FcγRI mAb at 4°C in the presence of sodium azide. (L) Coredistribution of FcγRI and CD13. (M–O) U‐937 cells were incubated with anti‐FcγRI mAb followed by phycoerythrin‐labeled secondary antibody for 20 min at 4°C. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 20 min to allow aggregation, and after fixation, CD33 staining was performed with a FITC‐labeled anti‐CD33 mAb at 4°C under the same conditions of CD13 staining in G–I.

For coredistribution experiments, FcγRI was aggregated at 37°C by anti‐FcγRI mAb followed by a secondary antibody. The cells were fixed, and staining of CD13 was conducted at 4°C. In these experiments, part of the population of CD13 redistributed to the zones of FcγRI aggregation (Fig. 6G, 6H, 6I). This redistribution was evident at 10 min of incubation at 37°C and reached its maximum at 20 min, after which it disappeared with both molecules located completely apart from one another (not shown).

When the opposite experiment was conducted, an almost complete redistribution of FcγRI to the zones of secondary antibody‐induced CD13 aggregation was seen (Fig. 6J, 6K, 6L) .

As a control, aggregation of FcγRI did not induce redistribution of other molecules such as CD33 (Fig. 6M, 6N, 6O) .

DISCUSSION

In the last few years, it has become increasingly evident that interactions between membrane molecules modulate cell signaling and thus, cell response. The possibility that FcγR‐mediated signaling is regulated by other membrane molecules has not been usually considered, and the generalized view is that FcγR‐mediated responses are mainly modulated by the balance between activatory and inhibitory isoforms of FcγRs involved in the interaction of the opsonized particle or antigen‐antibody complex with the cell. However, a possible functional cooperation between FcγRs and CD13 had already been suggested [ 23 , 24 ], and the results presented in this paper further support a possible functional involvement of CD13 in FcγR‐mediated functions in monocytic cells.

The first line of evidence suggesting a functional interaction between CD13 and FcγR is the finding that CD13 redistributes to the zones of contact between IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes and monocytic cells. Redistribution of CD13 to these zones is probably an active process, as incubation of monocytic cells with IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes at 4°C does not induce redistribution of CD13. This also suggests that CD13 redistribution is related to the initiation of the internalization process and induced by signals generated by the FcγRI aggregation rather than simply to the binding of IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes. Moreover, a significant fraction of CD13 molecules is internalized into the phagosomes with IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes, suggesting a role for CD13 in phagocytosis. Additionally, some CD13‐associated red fluorescence is also observed in the cytoplasm after phagocytosis. This may be attributable to endocytosis of CD13 occurring simultaneously to the phagocytic process. In this regard, Lohn et al. [ 33 ] reported endocytosis of CD13 at 37°C after occupation of the active center of CD13 with a mAb. Yet, another explanation for the presence of cytoplasmic CD13 can be the retrotranslocation of CD13 to the external phagosomal membrane (as suggested by CD13 distribution in Fig. 2A) and later, to the cytosol (Figs. 1M, and 2C). Houde et al. [ 34 ] have shown retrotranslocation of phagosomal contents to the external phagosomal membrane and their subsequent presence in the cytoplasm 60 min after incubation of macrophages with latex‐ovalbumin beads.

We have also shown that phagocytosable particles (EBS‐Ab) bound through FcγRI and CD13 are internalized more efficiently than similar particles bound to the monocyte through FcγRI only, in peripheral blood monocytes, monocyte‐derived macrophages, and U‐937 cells.

An unexpected finding was that binding of EBS‐Ab through CD13 alone was able to induce phagocytosis. Peripheral blood monocytes and U‐937 cells preincubated with the anti‐CD13 mAb or its F(ab)′2 fragments were able to ingest EBS‐Ab, but cells preincubated without anti‐CD13 mAb or with other murine mAb of the same isotype specific for another highly expressed molecule of monocytes (CD33) or for a nonrelated antigen (DNP) do not ingest EBS‐Ab. Furthermore, increasing doses of anti‐CD13 mAb go along with a parallel increase in phagocytosis of EBS‐Ab by monocytes. These findings show that phagocytosis of EBS‐Ab is mediated specifically by CD13. Thus, CD13 is not only able to positively modulate FcγRI‐mediated phagocytosis, but under certain circumstances, it is able to mediate phagocytosis to an extent similar to that of FcγRI (Fig. 3D), which might suggest that the increased phagocytic index observed when both molecules are engaged results from the sum of the individual phagocytosis. However, we cannot be certain of whether the effect of CD13 on FcγRI‐mediated phagocytosis when both receptors are coaggregated is additive or synergistic. One point that might suggest that it is not an additive event is that the magnitude of the effect is not directly proportional to the phagocytic index observed with CD13 alone. Conversely, for a synergistic effect to be invoked, one would expect that at a given point, the phagocytosis obtained by engaging CD13 and FcγRI should be significantly higher than the sum of the phagocytosis mediated by each receptor alone, and this was never observed. Nevertheless, the finding that CD13 is able to modulate FcγRI‐mediated phagocytosis is noteworthy regardless of the synergistic or additive origin of the phenomenon.

The biological significance of CD13‐mediated phagocytosis is difficult to establish at this point. From the dose‐response curve (Fig. 3D), optimal CD13‐mediated phagocytosis occurs at concentrations of anti‐CD13 mAb close to those required for saturation, indicating that an important fraction of CD13 should be engaged for phagocytosis to proceed. Whether these levels of CD13 engagement could be achieved in vivo is uncertain. Thus, CD13 participation in phagocytosis could be more relevant when CD13 is not the only receptor involved, especially when opsonization of the target is suboptimal.

Another important finding suggesting that CD13 regulates FcγRI signaling is the observation that the level and duration of Syk phosphorylation are increased after FcγRI and CD13 co‐cross‐linking as compared with the phosphorylation of Syk observed after FcγRI cross‐linking. This clearly shows that coaggregation of CD13 results in a modification of the biochemical signal elicited by FcγRI cross‐linking. The absolute requirement of Syk during FcγR‐mediated phagocytosis is well established [ 35 ], and thus, it is tempting to propose that this effect could be related to the increased phagocytosis observed when the particle is able to cross‐link FcγRI and CD13. It is interesting that cross‐linking of CD13 alone does not induce changes in the level of Syk phosphorylation, suggesting that CD13 cross‐linking only affects the level of Syk phosphorylation when it is coaggregated with FcγRI. As CD13 was able to mediate phagocytosis, the biochemical pathways involved in this phenomenon are apparently independent of Syk phosphorylation. These results are in line with those of Navarrete Santos et al. [ 23 ], who showed that inhibitors of tyrosine kinases were not able to block the initial Ca++ peak induced by CD13 cross‐linking in monocytes.

Finally, we have shown that although in a fraction of resting U‐937 cells, FcγRI and CD13 appear to distribute independently of each other, in those cells in which CD13 is polarized to a distinct zone of the membrane FcγRI is found to colocalize with it. Moreover, when aggregation of FcγRI is induced by an anti‐FcγRI mAb and a secondary antibody, part of the CD13 population redistributes to the zones of FcγRI aggregation. Conversely, aggregation of CD13 by anti‐CD13 and secondary antibody induces an almost complete redistribution of FcγRI in peripheral blood monocytes and U‐937 cells. As a control, FcγRI aggregation does not induce redistribution of CD33.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that FcγR aggregation (induced by IgG‐opsonized erythrocytes or secondary antibodies) induces coredistribution of CD13, a phenomenon that could be of functional relevance, as under experimental conditions in which both molecules are coaggregated (i.e., phagocytosis of EBS‐Ab and co‐cross‐linking for Syk phosphorylation determinations), a positive modulation of the FcγR‐induced signal is observed. The in vivo significance of the functional interaction between CD13 and FcγRI remains to be established. An intriguing possibility is that CD13 establishes interactions with pathogen‐derived molecules and that when CD13 and FcγRs bind to their ligands (i.e., an IgG‐opsonized and CD13 ligand‐containing pathogen), a positive modulation of the FcγR‐mediated signal occurs. Although a natural ligand for human CD13 on the surface of a phagocytable pathogen has not been described, its role as a viral receptor is well known, and in the insect Manduca sexta and other insect species, CD13 binds the Cry1A(c) toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis [ 36 ]. Besides, Galectin‐4 has been reported to act as a ligand for CD13 in the small intestinal brush border epithelia, and as a result of the role of galectins as opsonins [ 37 , 38 ], an enticing possibility is that these molecules function as ligands for CD13 in monocytes during phagocytosis. Finally, molecules known to be substrates or inhibitors of CD13 could be regarded as ligands in that they may trigger CD13‐mediated signals, which given the extent of CD13 substrates described, would be of great relevance in vivo.

In addition, the participation of aminopeptidases in the processing of N‐terminal‐extended peptides is now well accepted [ 39 ], and a role for CD13 in the trimming of peptides in antigen‐presenting cells, for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I‐ and MHC class II‐associated peptide generation, has been described [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Our results could point to a role of phagosome‐internalized CD13 in processing peptides after phagocytosis.

It has been reported that part of the CD13 population is associated with lipid rafts [ 43 ]. FcγRs as well as other MIRRs, such as BCR, TCR, and FcɛRI, are mostly excluded from lipid rafts but translocate into them upon clustering [ 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ]. Furthermore, there are indications that coreceptors influence the residency of MIRRs in rafts [ 49 ]. Preliminary results in our laboratory show colocalization among FcγRI, CD13, and ganglioside M1 in the zones of polarization (unpublished results). Thus, it is tempting to suggest that CD13 could modify the affinity of FcγRs for rafts maintaining their residency there for longer periods of time. This could explain the prolongation in the peak level of Syk phosphorylation that we have observed, as Src family kinases responsible for the initial phosphorylation of tyrosines of the immunoreceptor tyrosine‐based activation motif reside predominantly in these membrane domains, and Syk itself has been shown to relocate into rafts after FcɛRI aggregation [ 50 ]. Furthermore, the population of CD13 colocalizing with FcγRI during phagocytosis could correspond to that associated with rafts, taking into account that a role for lipid rafts has already been demonstrated in phagocytosis [ 51 ].

The results presented in this paper demonstrate that CD13 is able to modulate FcγR‐mediated responses. Further studies are necessary to better characterize this phenomenon to establish its physiological importance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from DGAPA, UNAM (Grant 213701), and CONACYT (Grant 45092). We thank Dr. Meenhard Herlyn (Wistar Institute) for the kind donation of the hybridoma producing anti‐CD13 mAb and Dr. Daniel Rodríguez‐Pinto for carefully reading the manuscript. P. M‐O. was supported by a fellowship from Dirección General de Estudios de Posgrado, UNAM.

REFERENCES

- 1. Daëron, M. (1997) Fc receptor biology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 203–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ravetch, J. V. , Bolland, S. (2001) IgG Fc receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19, 275–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cox, D. , Greenberg, S. (2001) Phagocytic signaling strategies: Fcγ receptor‐mediated phagocytosis as a model system. Semin. Immunol. 13, 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barrionuevo, P. , Beigier‐Bompadre, M. , Fernandez, G. C. , Gomez, S. , Alves‐Rosa, M. F. , Palermo, M. S. , Isturiz, M. A. (2003) Immune complex‐FcγR interaction modulates monocyte/macrophage molecules involved in inflammation and immune response. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 133, 200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clynes, R. , Ravetch, J. V. (1995) Cytotoxic antibodies trigger inflammation through Fc receptors. Immunity 3, 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takai, T. (2002) Roles of Fc receptors in autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 580–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ioan‐Facsinay, A. , de Kimpe, S. J. , Hellwig, S. M. , van Lent, P. L. , Hofhuis, F. M. , van Ojik, H. H. , Sedlik, C. , da Silveira, S. A. , Gerber, J. , de Jong, Y. F. , Roozendaal, R. , Aarden, L. A. , van den Berg, W. B. , Saito, T. , Mosser, D. , Amigorena, S. , Izui, S. , van Ommen, G. J. , van Vugt, M. , van de Winkel, J. G. , Verbeek, J. S. (2002) FcγRI (CD64) contributes substantially to severity of arthritis, hypersensitivity responses, and protection from bacterial infection. Immunity 16, 391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lanier, L. (2001) Face off—the interplay between activating and inhibitory immune receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13, 326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mina‐Osorio, P. , Ortega, E. (2004) Signal regulators in FcR‐mediated activation of leukocytes? Trends Immunol. 25, 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hooper, N. (1994) Families of zinc metalloproteases. FEBS Lett. 354, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olsen, J. , Kokholm, K. , Noren, O. , Sjostrom, H. (1997) Structure and expression of aminopeptidase N. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 421, 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pierelli, L. , Teofili, L. , Menichella, G. , Rumi, C. , Paolini, A. , Iovino, S. , Puggione, P. L. (1993) Further investigations on the expression of HLA‐DR, CD33 and CD13 surface antigens in purified bone marrow and peripheral blood CD34+ haematopoietic progenitor cells. Br. J. Haematol. 84, 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bauvois, B. (2004) Transmembrane proteases in cell growth and invasion: new contributors to angiogenesis? Oncogene 23, 317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Woodhead, V. E. , Stonehouse, T. J. , Binks, M. H. , Speidel, K. , Fox, D. A. , Gaya, A. , Hardie, D. , Henniker, A. J. , Horejsi, V. , Sagawa, K. , Skubitz, K. M. , Taskov, H. , Todd III, R. F. , van Agthoven, A. , Katz, D. R. , Chain, B. M. (2000) Novel molecular mechanisms of dendritic cell‐induced T cell activation. Int. Immunol. 12, 1051–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yeager, C. L. , Ashmun, R. A. , Williams, R. K. , Gaudellicko, C. B. , Shapiro, L. H. , Look, A. T. , Holmes, K. V. (1992) Human aminopeptidase N is a receptor for human coronavirus 229E. Nature 357, 420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sodeberg, C. , Giugni, T. D. , Zaia, J. A. , Larsson, S. , Wahlberg, J. M. , Moller, E. (1993) CD13 (human aminopeptidase N) mediates human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 67, 6576–6585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Larsson, S. , Sodeberg‐Naucler, C. , Moller, E. (1998) Productive cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection exclusively in CD13 positive peripheral blood mononuclear cells from CMV‐infected individuals: implications for prevention of CMV transmission. Transplantation 65, 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu, X. J. , Luo, C. , Lin, J. C. , Hao, P. , He, Y. Y. , Guo, Z. M. , Qin, L. , Su, J. , Liu, B. S. , Huang, Y. , Nan, P. , Li, C. S. , Xiong, B. , Luo, X. M. , Zhao, G. P. , Pei, G. , Chen, K. X. , Shen, X. , Shen, J. H. , Zou, J. P. , He, W. Z. , Shi, T. L. , Zhong, Y. , Jiang, H. L. , Li, Y. X. (2003) Putative hAPN receptor binding sites in SARS‐CoV spike protein. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 24, 481–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoffmann, T. , Faust, J. , Neubert, K. , Ansorge, S. (1993) Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) and aminopeptidase N (CD13) catalyzed hydrolysis of cytokines and peptides with N‐terminal cytokine sequences. FEBS Lett. 336, 61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ward, P. E. , Benter, I. F. , Dick, L. , Wilk, S. (1990) Metabolism of vasoactive peptides by plasma and purified renal aminopeptidase. Biochim. Pharmacol. 40, 1725–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chomarat, P. , Rissoan, M. C. , Pin, J. J. , Banchereau, J. , Miossec, P. (1995) Contribution of IL‐1, CD14 and CD13 in the increased IL‐6 production induced by in vitro monocyte‐synoviocyte interactions. J. Immunol. 155, 3645–3652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kanayama, N. , Kajiwara, Y. , Goto, J. , el Maraduy, E. , Maehara, K. , Andou, K. , Terao, T. (1995) Inactivation of interleukin‐8 by aminopeptidase N (CD13). J. Leukoc. Biol. 57, 129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Santos, A. N. , Langner, J. , Herrmann, M. , Riemann, D. (2000) Aminopeptidase N/CD13 is directly linked to signal transduction pathways in monocytes. Cell. Immunol. 201, 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. MacIntyre, E. A. , Roberts, P. J. , Jones, M. , van der Schoot, C. V. E. , Favalaro, E. J. , Tidman, N. (1989) Activation of human monocytes occurs on cross‐linking monocytic antigens to an Fc receptor. J. Immunol. 142, 2377–2383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olsen, J. , Cowell, G. M. , Konigshofer, E. (1988) Complete amino acid sequence of human intestinal aminopeptidase N as deduced from cloned cDNA. FEBS Lett. 238, 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Löhn, M. , Mueller, C. , Thiele, T. , Kähne, D. , Riemann, D. , Lagner, J. (1997) Aminopeptidase N‐mediated signal transduction and inhibition of proliferation of human myeloid cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 421, 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Navarrete Santos, A. , Langner, J. , Riemann, D. (2000) Enzymatic activity is not a precondition for the intracellular calcium increase mediated by mAbs specific for aminopeptidase N/CD13. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 477, 43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tokuda, N. , Levy, R. (1996) 1,25‐Dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates phagocytosis but suppresses HLA‐DR and CD13 antigen expression in human mononuclear phagocytes. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 211, 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Montaner, L. , Collin, M. , Herbein, G. (1996) Human monocytes: isolation, cultivation, and applications In Weir's Handbook of Experimental Immunology (Herzenberg L., Weir D. M., Herzenberg L., Blackwell C., eds.), Cambridge, MA, Blackwell, 155.1–155.11. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Davies, J. , Gordon, S. (2004) Isolation and culture of human macrophages In Basic Cell Culture Protocols (Helgason C., Miller C., eds.), Totowa, NJ, Humana, 105–116 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Edberg, J. , Kimberly, R. (1992) Receptor‐specific probes for the study of Fcγ receptor‐specific function. J. Immunol. Methods 148, 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lebel‐Binay, S. , Lagaudière, C. , Fradelizi, D. , Conjeaud, H. (1995) CD82, tetra‐span‐transmembrane protein, is a regulated transducing molecule on U‐937 monocytic cell line. J. Leukoc. Biol. 57, 956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lohn, M. , Mueller, C. , Lagner, J. (2002) Cell cycle retardation in monocytoid cells induced by aminopeptidase N (CD13). Leuk. Lymphoma 43, 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Houde, M. , Bertholet, S. , Gagnon, E. , Brunet, S. , Goyette, G. , Laplante, A. , Princiotta, M. , Thibault, P. , Sacks, D. , Desjardins, M. (2003) Phagosomes are competent organelles for antigen cross‐presentation. Nature 425, 402–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crowley, M. , Costello, P. S. , Fitzer‐Attas, C. J. , Turner, M. , Meng, F. , Lowell, C. , Ttybulewicz, V. L. , de Franco, A. L. (1997) A critical role for Syk in signal transduction and phagocytosis mediated by Fcγ receptors on macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 186, 1027–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knight, P. J. , Carroll, J. , Ellar, D. J. (2004) Analysis of glycan structures on the 120 kDa aminopeptidase N of Manduca sexta and their interactions with Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 34, 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Danielsen, M. E. , Deurs, B. (1997) Galectin‐4 and small intestinal brush border enzymes form clusters. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 2241–2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mandrell, R. E. , Apicella, M. A. , Lindstedt, R. , Leffler, H. (1994) Possible interaction between animal lectins and bacterial carbohydrates. Methods Enzymol. 236, 231–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rock, K. , York, I. , Goldberg, A. (2004) Post‐proteasomal antigen processing for major histocompatibility complex class I presentation. Nat. Immunol. 5, 670–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Amoscato, A. , Prenovitz, D. , Lotze, M. (1998) Rapid extracellular degradation of synthetic class I peptides by human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 161, 4023–4032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Larsen, S. L. , Pedersen, L. O. , Buus, S. , Stryhn, A. (1996) T cell responses affected by aminopeptidase N (CD13)‐mediated trimming of major histocompatibility complex class II‐bound peptides. J. Exp. Med. 184, 183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dong, X. , An, B. , Salvuci, L. , Storkus, W. , Amoscato, A. , Salter, R. (2000) Modification of the amino terminus of a class II epitope confers resistance to degradation by CD13 on dendritic cells and enhances presentation to T cells. J. Immunol. 164, 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Navarrete Santos, A. , Roentsch, J. , Danielsen, M. , Lagner, J. , Riemann, D. (2000) Aminopeptidase N/CD13 is associated with raft membrane microdomains in monocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269, 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kono, H. , Suzuki, T. , Yamamoto, K. , Okada, M. , Yamamoto, T. , Honda, Z. I. (2002) Spatial raft coalescence represents an initial step in FcγR signaling. J. Immunol. 169, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kwiatkowska, K. , Frey, J. , Sobota, A. (2003) Phosphorylation of FcγRIIA is required for the receptor‐induced actin rearrangement and capping: role of membrane rafts. J. Cell Sci. 116, 537–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheng, P. C. , Dykstra, M. L. , Mitchell, R. N. , Pierce, S. K. (1999) A role for lipid rafts in B cell antigen receptor signaling and antigen targeting. J. Exp. Med. 190, 1549–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Langlet, C. , Bernard, A. M. , Drevot, P. , He, H. T. (2000) Membrane rafts and signaling by the multichain immune recognition receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12, 250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Montixi, C. , Langlet, C. , Bernard, A. M. , Thimoniev, J. C. , Dubois, M. A. , Wurbel, J. P. , Chauvin, M. , Pierres, He, H. T. (1998) Engagement of T cell receptor triggers its recruitment to low‐density detergent‐insoluble membrane domains. EMBO J. 17, 5334–5348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cherukuri, A. , Cheng, P. , Sohn, H. , Pierce, S. (2001) The CD19/CD21 complex functions to prolong B cell antigen receptor signaling from lipid rafts. Immunity 14, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Field, K. A. (1997) Compartmentalized activation of the high‐affinity immunoglobulin E receptor within membrane domains. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 4276–4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dermine, J. F. , Duclos, S. , Garin, J. (2001) Flotilin‐1‐enriched rafts domains accumulate on maturing phagosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18507–18512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]