Abstract

This article describes an integrated fourth‐year course in catastrophe preparedness for students at the New York University College of Dentistry (NYUCD). The curriculum is built around the competencies proposed in “Predoctoral Dental School Curriculum for Catastrophe Preparedness,” published in the August 2004 Journal of Dental Education. We highlight our experience developing the program and offer suggestions to other dental schools considering adding bioterrorism studies to their curriculum.

Keywords: catastrophe preparedness, dental school curriculum, senior dental students, competencies

Due to the changes this nation has undergone since September 11, 2001, the need for a large force of health care providers trained to react to a major disaster in a surge environment, where the need for medical services far exceeds the resources available, has grown considerably. In an attempt to ensure that the public and private health care systems in the United States are capable of responding to emergencies, the federal government has directed financial and logistic resources to strengthen the emergency‐response system, create medication stockpiles, and improve the public health infrastructure. Emergency medicine will always have to be ready to confront another crisis, and in many of these catastrophic events, as we have recently seen during Katrina, the emergency medical system itself may be overwhelmed and/or totally crippled. As a consequence of the heightened awareness and needs associated with emergency response, new requirements have been proposed for the dental profession to help meet the special needs of society in the event of a disaster.

In June 2002 the American Dental Association (ADA) held a meeting to identify potential roles for dentists in response to a bioterrorism attack. One area of concern expressed at that time was what role dental schools should play in emergency preparedness. The participants at this meeting concluded that bioterrorism training should occur in the predoctoral dental curriculum and should include training that allows dental students to recognize disease, aid in triage, implement preventive measures, and assist in treatment under the direction of emergency‐response agencies. 1

In this article we describe New York University College of Dentistry's (NYUCD) effort to build a catastrophe preparedness curriculum for our predoctoral students. The faculty of NYUCD used the competencies, goals, and objectives as proposed by More et al. for the development of this curriculum (see Table 1). These competencies are based on the recognition that the knowledge and skills possessed by the average dental student upon graduation may be utilized by the public health care system in times of crisis. 2

Table 1.

Catastrophe preparedness competencies

| Competency 1: | Describe the potential role of dentists in the first/early response in a range of catastrophic events. |

| Competency 2: | Describe the chain of command in the national, state, and/or local response to a catastrophic event. |

| Competency 3: | Demonstrate the likely role of a dentist in an emergency response and participate in a simulation/drill. |

| Competency 4: | Demonstrate the possible role of a dentist in all communications at the level of a response team, the media, the general public, and patient and family. |

| Competency 5: | Identify personal limits as a potential responder and sources that are available for referral. |

| Competency 6: | Apply problem‐solving and flexible thinking to unusual challenges within the dentist's functional ability and evaluate the effectiveness of the actions that are taken. |

| Competency 7: | Recognize deviations from the norm, such as unusual cancellation patterns, symptoms of seasonal illnesses that occur out of the normal season, and employee absences, that may indicate an emergency and describe appropriate action. |

NYUCD's Catastrophe Preparedness Curriculum

NYUCD has implemented a new experience for a dental student that incorporates four components: curriculum integration, modular components, an actively participating senior course, and continuous evaluation. Initial outcomes assessment indicated a very positive response from the NYUCD graduating class of 2005. 3

Supplemental Units in the First Three Years

NYUCD has approximately 340 students enrolled in the senior class (D4). Freshmen, sophomores, and juniors are introduced to the subject of bioterrorism preparedness by supplementing the established curriculum with units of instruction in modular form, as follows:

Freshman Curriculum (D1): Shelter in Place, Emergency Evacuations, and Fire Hazard, as part of the freshman orientation. Total D1: 1.0 hour.

Sophomore Curriculum (D2): Students are introduced to pathogens that can be used as agents of bioterrorism during the General Pathology and Infectious Diseases course. Total D2: 7 hours. Topics include:

-

Bacillus and Clostridium:

B. anthracis: detailed review of anthrax and the unique properties of B. anthracis, its spore‐former, toxins, capsule, and ease of dissemination that make it such a good potential bioweapon;

C. botulinum: review of its toxin, how it works in the host, and how it may be spread;

gram‐negative pathogens: plague and tularemia—properties and modes of transmission of these non‐spore forming bacteria;

DNA viruses: smallpox virus—properties and life cycle of pox viruses, campaign for the eradication of smallpox;

RNA viruses: discussion of the viruses that cause viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHF) as well as the attributes of the SARS virus;

microbial agents of bioterrorism: discussion of all of the biological agents in the CDC's category A list—anthrax, botulism, plague, smallpox, tularemia, and VHFs (viral hemorrhagic fever). Aspects covered: agents, how they may be spread, and why a bioterrorist might select them. Additional topics include ricin and briefly CDC category B and category C agents.

Junior Curriculum (D3): Students are introduced to oral and systemic manifestations of bioterrorist agents including clinical signs and symptoms. This topic is introduced as part of the course entitled “Care of the Medically Complex Patients.” Total D3: 3 hours. Topics addressed are:

clinical symptoms of anthrax, smallpox, and plague;

smallpox vaccine; and

catastrophe preparedness—chemical agents, nerve gases.

Senior Curriculum (D4)

After experiencing this curriculum during their first three years, the senior students (D4s) have already acquired the basic foundation knowledge in the biomedical sciences, including biological agents; knowledge of chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive (CBRNE) weapons; CPR training; wound management; and infection control procedures. In addition, they have experienced the impact of an ethics course that explores a dentist's obligation to the community.

After developing the core educational content for the first three years of the curriculum, the faculty addressed the challenge of developing a stand‐alone D4 program that would build on the previously described curriculum components and work in conjunction with their senior‐year patient care and patient management experience.

Key questions included:

What competencies should be reinforced?

What instructional methods should be used? (lecture, roleplay, seminars)

How should students’ attitudes and the course effectiveness be evaluated?

With these questions guiding the planning process, a fourth‐year course was developed for implementation in the spring semester within two months of graduation. Many senior dental students at that time of the year are deeply concerned with passing regional licensing examinations, completing their curriculum requirements, and preparing for their professional futures. Based on our knowledge of typical senior students’ priorities and distractions during their last semester in dental school, it was evident that the emergency preparedness course material had to be presented in a particularly stimulating and attention‐grabbing manner.

The course developed for these fourth‐year dental students was organized around four questions:

Why should dentists be concerned and involved?

How can dentists respond to a catastrophe as part of the organized public health response system?

What additional practical training is useful for dentists?

How can the average general dentists prepare to protect themselves if a disaster occurs when they are in their offices?

The first question—why should dentists be concerned and involved with catastrophe preparedness?—is of such critical importance that it was addressed in an introductory lecture delivered by the dean of the dental school. The lecture emphasized to the students their obligation to the profession, to the community, to their own families, and to their country. The lecture reminded students of the skills they bring with them in the event of an emergency. The opportunities available to join an organized response effort such as the Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) are discussed. Additionally, the dean described the abilities that graduate dentists can utilize in an emergency situation; for example, if dentists can accurately administer an inferior alveolar nerve block injection in the recesses of the mouth, they can certainly “hit” the large deltoid muscle in the arm to administer a smallpox vaccination with minimal training. 4

The second course theme addressed the question of why dentists should participate in the community's established and organized disaster response system. The approach taken to achieve this objective was to use an existing surge response public health mechanism. NYUCD has had a close relationship with the New York City Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) for several years, ever since NYUCD and the city conducted a simulated Point of Dispensing (POD) exercise together. The MRC developed by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) consists of a multidisciplinary group of volunteer health professionals, including physicians, pharmacists, dentists, nurses, mental health practitioners, and others, who can be mobilized rapidly during a public health emergency. The MRC/NYC works in partnership with professional associations, universities, and hospitals. As an example, a bioterrorist attack may require mass antibiotic/vaccination prophylaxis. To dispense antibiotics or vaccine to the public, Point‐of‐Dispensing clinics (PODs) would be set up. POD functions include medical evaluation, triage, vaccination or distribution of medication, and line management. Clinical/support roles are assigned to each professional based on his or her skills and licensure. 5

During a three‐hour POD drill, with an improvised scenario, the NYUCD's main auditorium was transformed into a smallpox vaccine dispensing center as our senior students acted as both members of the MRC (triaging, evaluating, dispensing, and inoculating the public) and as patients eagerly looking for answers and protection. The exercise was filmed for use in future classes and to help demonstrate that dentists, with their strong background in infection control, biological agents, collecting medical histories, and patient management, can relatively quickly be organized into an effective, much‐needed component of the catastrophe response system.

The third theme of the D4 course addressed the question “What additional practical training is useful for dentists?” In 2003, the American Medical Association (AMA), in partnership with four major medical centers and three national health organizations, established the National Disaster Life Support (NDLS) training program to better prepare health care professionals and emergency response personnel for mass casualty events. The NDLS courses stress a comprehensive all‐hazards approach to help physicians and other health professionals deal with catastrophic emergencies from terrorist acts as well as from explosions, fires, natural disasters (such as hurricanes and floods), and infectious diseases. The program consists of three levels of courses of increasing clinical complexity: 1) Core Disaster Life Support (CDLS), 2) Basic Disaster Life Support (BDLS), and 3) Advanced Disaster Life Support (ADLS). 6

The first component (CDLS) of this hierarchal set of training courses was chosen for its practicality and to introduce those students interested in this material to the possibilities for further training. Core Disaster Life Support is a four‐hour instructor‐led course designed for all public health care personnel and social workers, clergy, mental health personnel, and planners. CDLS is intended to provide a basic uniform standard of competencies, skills, and knowledge to health care and public health responders for weapons of mass destruction (WMD) response. There was strong agreement among the faculty involved in our bioterrorism preparedness curriculum that since this “formal” presentation already existed, there was no need to initiate and develop another appropriate program.

In the CDLS course, participants learn to:

define All‐Hazards Terminology,

recognize potential public health emergencies (PHE) and their causes, risks, and consequences,

define the D‐I‐S‐A‐S‐T‐E‐R™ paradigm,

list scene priorities of a mass casualty incident (MCI) response,

describe pre‐hospital and hospital medical components of a disaster incident response,

describe personal protective equipment (PPE) and decontamination, and

describe the role of the local public health system in PHEs. 6

After presentation of the course and a short twenty‐five‐question examination, the AMA offers a certificate of completion with name and degree to each participant. Three hundred and twenty of NYUCD's senior students who graduated in 2005 completed the CDLS course and received certification. It was very rewarding to see how proud our seniors were of their certificates and the fact that they had completed formal training in Core Disaster Life Support.

The fourth component of the D4 catastrophe preparedness curriculum addresses awareness and personal protection. NYUCD has an active Emergency Plan and a Shelter‐in–Place protocol in place. This is a plan that would allow the college to prepare, respond, and recover from any man‐made or natural disaster during the first seventy‐two hours of an incident. It is focused on the realization that the major decision to be made is whether we should evacuate the building or use the inherent protection of the structure to shelter in place. The NYUCD student body is therefore aware of the need for anticipating and planning for a possible attack or disaster. It has been shown that the positive behavioral response of individuals goes a long way toward mitigating the consequences of a serious event and has important implications for the practical management of a disaster scene.

Using this as the basis to achieve the final course objective, the senior students were required to work in groups of four, on their own time, to develop either an evacuation and/or a shelter‐in‐place plan for the type of dental office or clinic in which they plan to practice. Students could tailor the plan to a specific bioterrorist agent (for example, a dirty bomb, sarin gas, a biological weapon) or make it generic for either a natural or a man‐made disaster. Interestingly, many students used a likely event related to the particular state in which they thought they would practice. Earthquakes were an issue for those who planned for California, tornadoes for the potential midwesterners, and hurricane‐related damage in the Southeast.

Faculty with a strong background in catastrophe preparedness then selected and presented to the whole class the more interestingly detailed and thought‐provoking scenarios submitted and moderated the class discussions that followed. 7

At the completion of this first‐time course, the dean and the curriculum committee were interested in determining if the curriculum helped students achieve the bioterrorism competencies in the predoctoral dental curriculum. Evaluation questions included:

Did students graduate with sufficient knowledge of the clinical signs and symptoms and prevention strategies of the most likely bioterrorist agents (Class A agents)?

Did students graduate sufficiently empowered to react positively to protect their patients, staff, families, and themselves from the multiple hazards of these agents and other hazards?

Did students graduate with sufficient knowledge of the resources available to improve and sharpen their skills and to familiarize themselves with their community response plan?

Most importantly, did students graduate with a desire and willingness to contribute to catastrophe preparedness with an understanding of the ethical issues and obligations involved?

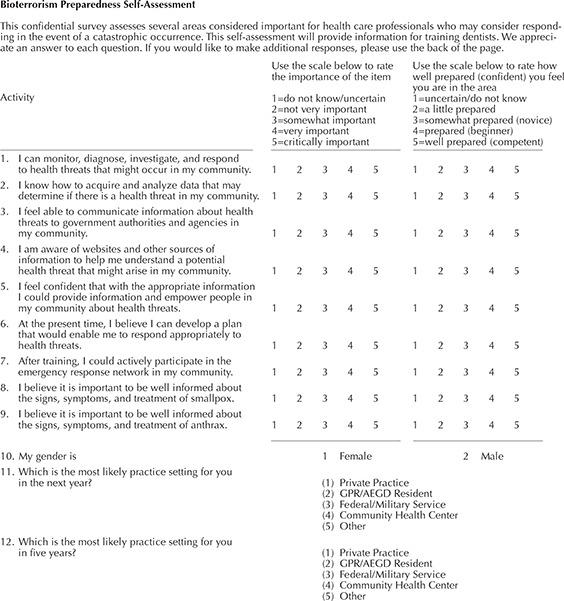

To assess these questions, a survey was developed as a pre‐test and post‐test to assess the attitude of the D4 students about various aspects of catastrophe preparedness. The underlying assumption was that students’ attitudes about catastrophe preparedness would be changed as a consequence of the curriculum experiences described in this article. A survey (which had received an IRB‐exempt designation) was administered on the first day of the D4 course. The survey appears in Figure 1. Senior students were requested to self‐assess their knowledge about bioterrorism and their confidence in their competency on that issue. The same survey was administered after the course.

Figure 1.

Students’ self‐assessment survey

The preliminary data from the pilot program suggested that student attitudes were changed after the course. They saw more aspects of catastrophe preparedness as “important” and said the program made them feel more “confident” to assume a role as a responder. 3 We describe only the initial impressions of data here because we have yet to have it fully statistically analyzed and it is secondary to the description of the program this article presents—a program that we feel should invoke discussion and debate in the dental academic community. It is our intention to analyze the data and present the findings of the student assessment in a future article that will offer a full and complete picture of the students’ response. Following the initial More et al. article and this current article, an analytical third article would complete the sequence regarding catastrophic preparedness training for dental students.

Conclusion

The senior curriculum described in this article consists of twelve hours of organized presentations, roleplaying, and seminars. At NYUCD, we believe a capstone course of this nature goes a long way in fulfilling the community obligation for dental schools to train dentists in the core competencies required to be able to lend additional support to the public health infrastructure in a surge environment.

A recent feature article in the New York Times describing NYUCD's unique efforts in mandating terrorism preparedness for its students summed up the college's goal: “All graduates are now required to have a fundamental working knowledge of the proper response to a variety of natural and terrorist threats.” 8

REFERENCES

- 1. Guay A.H. Dentistry's response to bioterrorism: a report of a consensus workshop. J Am Dent Assoc 2002; 133 (Sept.): 1181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. More F.G., Phelan J., Boylan R., Glotzer D.L., Psoter W., Robbins M., et al. Predoctoral dental school curriculum for catastrophe preparedness. J Dent Educ 2004; 68: 851–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. More F.G., Department of Epidemiology and Health Promotion, NYUCD. Personal communication, June 2005.

- 4. Focus of NYS Dental Foundation Conference is bio‐terrorism and public health emergencies. N Y State Dent J 2004; 70 (May): 5. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Medical Reserve Corps/NYC. At: http://www.gnyha.org/eprc/general/presentations/20040809_mrc-nyc.pdf. Accessed: July 25, 2005.

- 6. AMA Center for Public Health Preparedness and Disaster Response. At: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/12607.html. Accessed: July 25, 2005.

- 7. Glotzer D.L., More F.G. Compilation of senior dental student submissions on Protective Action Plans submitted as course requirement. New York: New York University College of Dentistry, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morgan R. Dentists prepared to be on front line of civil defense. The New York Times, August 2, 2005, F6.