Abstract

Background

No comprehensive analysis is available on the viral etiology and clinical characterization among children with severe acute lower respiratory tract infection (SALRTI) in Southern China.

Methods

Cohort of 659 hospitalized children (2 months to 14 years) with SALRTI admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) in the Guangzhou from May 2015 to April 2018 was enrolled in this study. Nasopharyngeal aspirate specimens or induced sputum were tested for eight categories respiratory viral targets. The viral distribution and its clinical characters were statistically analyzed.

Results

Viral pathogen was detected in 326 (49.5%) of children with SALRTI and there were 36 (5.5%) viral coinfections. Overall, the groups of viruses identified were, in descending order of prevalence: Influenza virus (IFV) (n = 94, 14.3%), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (n = 75, 11.4%), human rhinovirus (HRV) (n = 56, 8.5%), adenovirus (ADV) (n = 55, 8.3%), parainfluenza (PIV) (n = 47, 7.1%), human coronavirus (HCoV) (n = 15, 2.3%), human metapneumovirus (HMPV) (n = 14, 2.1%) and human bocavirus (HBoV) (n = 11, 1.7%). The positive rate in younger children (< 5 years) was significantly higher than the positive rate detected in elder children (> 5 years) (52.5% vs 35.1%, P = 0.001). There were clear seasonal peaks for IFV, RSV, HRV, ADV, PIV, and HMPV. And the individuals with different viral infection varied significantly in terms of clinical profiles.

Conclusions

Viral infections are present in a consistent proportion of patients admitted to the PICU. IFV, RSV, HRV, and ADV accounted for more than two‐thirds of all viral SALRTI. Our findings could help the prediction, prevention and potential therapeutic approaches of SALRTI in children.

Keywords: epidemiology, respiratory tract, severe acute lower respiratory infection, virus

Highlight

Viral infections are present in a consistent proportion of patients admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

Influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, human rhinovirus and adenovirus accounted for more than two‐thirds of all viral SALRTI.

1. INTRODUCTION

Acute lower respiratory tract infection (ALRTI) is one of the main causes of hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality in children.1, 2 Severe ALRTI (SALRTI) accounts for most hospital admissions in young children worldwide, with an estimated 11.9 million (95% confidence interval 10.3‐13.9 million) cases, whereas very SALRTI accounts for an estimated 3 million (2.1‐4.2 million) cases. Concomitantly, such infections resulted in about 2.8 million deaths worldwide in 2010.3, 4, 5 Children who suffer from SALRTI require intensive medical management, imposing a great societal burden, particularly in India, China, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Nigeria.6, 7

The etiological factor in young children is a viral infection or a combination of viral and bacterial infection, which is apparently different from that of ALRTI caused by bacteria in adults. Therefore, the lack of effective diagnostic methods for the identification of the etiological factor is the major reason why more than 50% of ALRTIs were treated unnecessarily and inappropriately with antibiotics, even in the case of viral infection.8 This often leads to serious consequences such as a high rate of antibiotic resistance,9 especially in virus‐infected children with SALRTI. Therefore, a better understanding of the epidemiology of viral respiratory tract infections in critically ill children is essential for the development of a novel strategy for SALRTI prevention, control, and treatment.

Although several studies have been conducted to investigate the prevalence of viral ALRTIs in Northern China, particularly in Beijing and Shanghai, the viral pathogens that cause ALRTI, especially those causing SALRTI, in Southern China have not yet been established. As a representative city in Southern China, Guangzhou is a first‐tier city with a high population density and disease mobility. To gain insight into respiratory viruses in children with SALRTI for future diagnosis and antiviral treatment, a comprehensive evaluation of viral etiology and clinical characterization was conducted among hospitalized children with SALRTI admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐Sen University between May 2015 and April 2018.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Ethics statement

This study was conducted in compliance with the protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐Sen University. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ guardians before enrollment.

2.2. Participants and clinical definitions

The study participants consisted of children admitted to the PICU of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐Sen University between May 2015 and April 2018. SALRTI was diagnosed according to the clinical guidelines recommended by the World Health Organization.10, 11 The eligibility and classification of the clinical syndromes of SALRTI were determined from each patient's original medical history and physical examination records. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (children > 5 years of age) sudden onset of fever > 38°C, cough or sore throat, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, and requiring hospitalization; (children < 5 years of age) meeting either (1) the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) criteria for pneumonia (any child 2 months to 5 years of age with cough or difficulty breathing and breathing faster than 60 breaths/min [infants < 2 months], breathing faster than 50 breaths/min (2‐12 months), or breathing faster than 40 breaths/min [1‐5 years]) or (2) the IMCI criteria for severe pneumonia (any child 2 months to 5 years of age with cough or difficulty breathing and any of the following general danger signs: unable to drink or breastfeed, vomits everything, convulsions, lethargic or unconscious, chest indrawing, or stridor in a calm child) and (3) requiring hospital admission. Nasopharyngeal aspirate (NPA) or induced sputum (IS) was collected from the patients at the first day of admission and transferred into the virus transport medium. Demographic information and medical test results were obtained using standardized forms.

2.3. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction tests

Viral nucleic acids were simultaneously extracted from 200 μL of NPA specimens or IS using QIAamp MinElute Virus Spin Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription of virus RNA was performed using Thermo Fisher Scientific Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the incubation procedure was performed as follows: 25℃ for 5 minutes, 42℃ for 60 minutes, and 70℃ for 5 minutes. cDNA was used for virus detection immediately or stored at −20℃ until further use. Each sample was tested simultaneously for the following eight categories of respiratory viruses: influenza virus (IFV) (five type A subtypes, including H1N1, H3N2, pandemic H1N1 2009, H5N1, and H7N9, as well as type B virus), parainfluenza types 1 to 4 (PIV1, PIV2, PIV3, and PIV4), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) type A and B, human metapneumovirus (HMPV), six strains of human coronavirus (HCoV, including HCoV‐229E, OC43, NL63, HKU1, SARS, and MERS), adenovirus (ADV), human rhinovirus (HRV), and human bocavirus (HBoV). These viruses were detected using either real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or reverse transcription‐PCR. The procedure was described previously,12, 13, 14, 15, 16 with specific primers and probes listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Primers and probes used for respiratory viruses screening

| Virus | Primer/probe | Sequence (5′‐3′) | Target gene | PCR product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFV‐A | IFV A‐F | GACCRATCCTGTCACCTCTGAC | M | 82 |

| IFV A‐R | AGGGCATTYTGGACAAAKCGTCTA | |||

| IFV A‐Probe | FAM‐TGCAGTCCTCGCTCACTGGGCACG‐BHQ1 | |||

| Seasonal H1N1‐H1‐F | CGAAATATTCCCCAAAGARAGCT | HA | 76 | |

| Seasonal H1N1‐H1‐R | CCCRTTATGGGAGCATGATG | |||

| Seasonal H1N1‐H1‐Probe | FAM‐TGGCCCAACCACACCGTAACCG‐BHQ1 | |||

| Seasonal H1N1‐N1‐F | GATGGGCTATATACACAAAAGACAACA | NA | 257 | |

| Seasonal H1N1‐N1‐R | TGCTGACCATGCAACTGATT | |||

| Seasonal H1N1‐N1‐Probe | FAM‐TATAGGGCCTTAATGAGCTGTCCTCTAGG‐BHQ1 | |||

| Seasonal H3N2‐H3‐F | ACCAGAGAAACAAACTAGAGGCATATT | HA | 120 | |

| Seasonal H3N2‐H3‐R | TGTCCTGTGCCCTCAGAATTT | |||

| Seasonal H3N2‐H3‐Probe | FAM‐CGGTTGGTACGGTTTCAGGCA‐BHQ1 | |||

| Seasonal H3N2‐N2‐F | TGTATCTGACCAACACCACCATAGA | NA | 77 | |

| Seasonal H3N2‐N2‐R | TTGCGGCTTTGACCAATTTC | |||

| Seasonal H3N2‐N2‐Probe | FAM‐AAGGAAATATGCCCCAAACTAGCAGAATAC‐BHQ1 | |||

| Pandemic H1N1‐H1‐F | TTATCATTTCAGATACACCAGT | HA | 179 | |

| Pandemic H1N1‐H1‐R | AATAGACGGGACATTCCT | |||

| Pandemic H1N1‐H1‐Probe | FAM‐CCACGATTGCAATACAACT‐BHQ1 | |||

| Pandemic H1N1‐N1‐F | CAGAGGGCGACCCAAAGAGA | NA | 93 | |

| Pandemic H1N1‐N1‐R | GGCCAAGACCAACCCACA | |||

| Pandemic H1N1‐N1‐Probe | FAM‐CACAATCTGGACTAGCGGGAGCAGCAT‐BHQ1 | |||

| H5N1‐H5‐F | GGAACTTACCAAATACTGTCAATTTATTCA | HA | 84 | |

| H5N1‐H5‐R | CCATAAAGATAGACCAGCTACCATGA | |||

| H5N1‐H5‐Probe | FAM‐TTGCCAGTGCTAGGGAACTCGCCAC‐BHQ1 | |||

| H7N9‐H7‐F | AGAGTCATTRCARAATAGAATACAGAT | HA | 159 | |

| H7N9‐ H7‐R | CACYGCATGTTTCCATTCTT | |||

| H7N9‐ H7‐Probe | FAM‐AAACATGATGCCCCGAAGCTAAAC‐BHQ1 | |||

| H7N9‐N9‐F | GTTCTATGCTCTCAGCCAAGG | NA | 153 | |

| H7N9‐N9‐R | CTTGACCACCCAATGCATTC | |||

| H7N9‐N9‐Probe | FAM‐TAAGCTRGCCACTATCATCACCRCC‐BHQ1 | |||

| IFV‐B | IFV B‐F | TGCCTACCTGCTTTMMYTRACA | M | 75 |

| IFV B‐R | CCRAACCAACARTGTAATTTTTCTG | |||

| IFV B‐Probe | FAM‐TGCTTTGCCTTCTCCA‐BHQ1 | |||

| RSV‐A | RSV A‐F | GCTCTTAGCAAAGTCAAGTTGAATGA | N | 82 |

| RSV A‐R | TGCTCCGTTGGATGGTGTATT | |||

| RSV A‐Probe | FAM‐ACACTCAACAAAGATCAACTTCTGTCATCCAGC‐BHQ1 | |||

| RSV‐B | RSV B‐F | GATGGCTCTTAGCAAAGTCAAGTTAA | N | 104 |

| RSV B‐R | TGTCAATATTATCTCCTGTACTACGTTGAA | |||

| RSV B‐Probe | FAM‐TGATACATTAAATAAGGATCAGCTGCTGTCATCCA‐BHQ1 | |||

| PIV1 | PIV1‐F | ATCTCATTATTACCYGGACCAAGTCTACT | HN | 128 |

| PIV1‐R | CATCCTTGAGTGATTAAGTTTGATGAATA | |||

| PIV1‐Probe | FAM‐AGGATGTGTTAGAYTACCTTCATTATCAATTGGTGATG‐BHQ1 | |||

| PIV2 | PIV2‐F | CTGCAGCTATGAGTAATC | NP | 119 |

| PIV2‐R | TGATCGAGCATCTGGAAT | |||

| PIV2‐Probe | FAM‐AGCCATGCATTCACCAGAAGCCAGC‐BHQ1 | |||

| PIV3 | PIV3‐F | ACTCTATCYACTCTCAGACC | NP | 106 |

| PIV3‐R | TGGGATCTCTGAGGATAC | |||

| PIV3‐Probe | FAM‐AAGGGACCACGCGCTCCTTTCATC‐BHQ1 | |||

| PIV4 | PIV4‐F | GATCCACAGCAAAGATTCAC | NP | 113 |

| PIV4‐R | GCCTGTAAGGAAAGCAGAGA | |||

| PIV4‐Probe | FAM‐TATCATCATCTGCCAAATCGGCAA‐BHQ1 | |||

| HMPV | HMPV‐F | CATAYAARCATGCTATATTAAAAGAGTCTC | NP | 162 |

| HMPV‐R | CCTATYTCTGCAGCATATTTGTAATCAG | |||

| HMPV‐Probe | FAM‐TGYAATGATGARGGTGTCACTGCRGTTG‐BHQ1 | |||

| HCoV‐229E | 229E‐F | CAGTCAAATGGGCTGATGCA | NP | 76 |

| 229E‐R | AAAGGGCTATAAAGAGAATAAGGTATTCT | |||

| 229E‐Probe | FAM‐CCCTGACGACCACGTTGTGGTTCA‐BHQ1 | |||

| HCoV‐NL63 | NL63‐F | GACCAAAGCACTGAATAACATTTTCC | NP | 109 |

| NL63‐R | ACCTAATAAGCCTCTTTCTCAACCC | |||

| NL63‐Probe | FAM‐AACACGCTTCCAACGAGGTTTCTTCAACTGAG‐BHQ1 | |||

| HCoV‐OC43 | OC43‐F | GAAGGTCTGCTCCTAATTCCAGAT | NP | 206 |

| OC43‐R | TTTGGCAGTATGCTTAGTTACTT | |||

| OC43‐Prob | FAM‐TGCCAAGTTTTGCCAGAACAAGACTAGC‐BHQ1 | |||

| HCoV‐HKU1 | HKU1‐F | CCTTGCGAATGAATGTGCT | Replicase 1b | 94 |

| HKU1‐R | TTGCATCACCACTGCTAGTACCAC | |||

| HKU1‐Probe | FAM‐TGTGTGGCGGTTGCTATTATGTTAAGCCTG‐BHQ1 | |||

| HCoV‐MERS | BetaCoV_NF1083 | CAAAACCTTCCCTAAGAAGGAAAAG | NP | 83 |

| BetaCoV_NF1165 | GCTCCTTTGGAGGTTCAGACAT | |||

| BetaCoV_NPr1110 | FAM‐ACAAAAGGCACCAAAAGAAGAATCAACAGACC‐BHQ1 | |||

| HCoV‐SARS | SARS‐F | GCATAYAAAACATTCCCACCAA | NP | 120 |

| SARS‐R | AGCCGCAGGAAGAAGAGTCA | |||

| SARS‐Probe | FAM‐ACTGATGAAGCTCAGCCTTTRCCGC‐BHQ1 | |||

| HRV | HRV‐F | TGGACAGGGTGTGAAGAGC | 5′UTR | 144 |

| HRV‐R | CAAAGTAGTCGGTCCCATCC | |||

| HRV‐Probe | FAM‐TCCTCCGGCCCCTGAATG‐BHQ1 | |||

| ADV | ADV‐F | GCCACGGTGGGGTTTCTAAACTT | Hexon | 132 |

| ADV‐R | GCCCCAGTGGTCTTACATGCACATC | |||

| ADV‐Probe | FAM‐TGCACCAGACCCGGGCTCAGGTACTCCGA‐BHQ1 | |||

| HBoV | HBoV‐F | TGCAGACAACGCYTAGTTGTTT | NS1 | 88 |

| HBoV‐R | CTGTCCCGCCCAAGATACA | |||

| HBoV‐Probe | FAM‐CCAGGATTGGGTGGAACCTGCAAA‐BHQ1 |

Note: K = G or T; M = A or C; R = A or G; S = G or C; Y = C or T; W = A or T; D = A or G or T; N = A or C or G or T.

Abbreviations: ADV, adenovirus; HBoV, human bocavirus; HCoV, human coronavirus; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; HRV, human rhinovirus; IFV, influenza virus; PIV, parainfluenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data obtained were entered into a database prepared with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Washington, DC). The distribution of viral findings was analyzed in terms of the following factors: (1) sex, (2) patient age, (3) seasonality of sampling, and (4) clinical characteristics of respiratory viruses. the χ 2 test and Fisher's exact test, performed with SPSS (v18.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL), were used for comparisons between groups when applicable. All tests were performed with a type I error of 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of patients with SALRTI in the PICU

During the investigation, 659 samples from patients with SALRTI were included in the analysis. In accordance with the study definition, repeated samples, defined as samples obtained within 30 days from the same area of the respiratory tract of a given patient, were excluded. Among patients with SALRTI, 82.7% were children under 5 years, with a median age of 1.86 years (interquartile range, 0.62‐4.43 years). In addition, 417 (63.3%) patients were male. Coughing and body temperature over 38°C were the most common symptoms (95.6% and 94.4%, respectively). All patients with SALRTI admitted to the PICU underwent a chest X‐ray examination; 507 (76.9%) patients were found to have radiographic evidence of pneumonia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of hospitalized patients with SALRTI

| Characteristics | All SALRTI (%) a (n = 659) | Any viral etiology (%) a (n = 326) | Negative (%) a (n = 333) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender group | ||||

| Male sex | 417 (63.3) | 202 (62.0) | 215 (64.6) | 0.489 |

| Female sex | 242 (36.7) | 124 (38.0) | 118 (35.4) | |

| Age group | ||||

| 2 mo‐1 y | 240 (36.4) | 133 (40.8) | 107 (32.1) | 0.006 |

| 1‐3 y | 160 (24.3) | 87 (26.7) | 73 (21.9) | |

| 3‐5 y | 145 (22.0) | 66 (20.2) | 79 (23.7) | |

| 5‐10 y | 70 (10.6) | 27 (8.28) | 43 (12.9) | |

| 10‐14 y | 44 (6.7) | 13 (4.0) | 31 (9.3) | |

| Clinical history and physical examination | ||||

| T ≥ 38.0°C | 622 (94.4) | 303 (92.9) | 319 (95.8) | 0.112 |

| Cough | 630 (95.6) | 310 (95.1) | 320 (96.1) | 0.530 |

| Runny nose | 165 (25.0) | 102 (31.3) | 63 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| Sore throat | 46 (7.0) | 28 (8.6) | 18 (5.4) | 0.109 |

| Sputum production | 404 (61.3) | 220 (67.5) | 184 (55.3) | 0.001 |

| Tachypnea | 262 (39.8) | 158 (48.5) | 104 (31.2) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty breathing | 411 (62.4) | 234 (71.8) | 177 (53.2) | <0.001 |

| Wheezing | 207 (31.4) | 148 (45.4) | 59 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| Radiographic evidence of pneumonia | 507 (76.9) | 252 (77.3) | 255 (76.6) | 0.825 |

| Lung rale sounds on auscultation | 460 (69.8) | 220 (67.5) | 240 (72.1) | 0.200 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||

| Asthma | 36 (5.5) | 27 (8.3) | 9 (2.7) | 0.002 |

| Heart failure | 51 (7.7) | 35 (10.7) | 16 (4.8) | 0.004 |

| Hematological disease | 63 (9.6) | 32 (9.8) | 31 (9.3) | 0.825 |

| Neuromuscular disease | 5 (0.8) | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 0.683 |

| Autoimmune disease | 42 (6.4) | 23 (7.1) | 19 (5.7) | 0.478 |

| Immunosuppression | 138 (20.9) | 78 (23.9) | 60 (18.0) | 0.062 |

| APACHE II score mean (SD) | 14.1 (4.3) b | 14.5 (4.6) b | 13.9 (3.9) b | <0.001 |

| Presenting clinical manifestations | ||||

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation | 170 (25.8) | 92 (28.2) | 78 (23.4) | 0.159 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 189 (28.7) | 103 (31.6) | 86 (25.8) | 0.102 |

| Vasoactive drugs | 177 (26.9) | 89 (27.3) | 88 (26.4) | 0.800 |

| Continuous venovenous hemofiltration | 18 (2.7) | 7 (2.1) | 11 (3.3) | 0.363 |

| Corticoids | 206 (31.3) | 119 (36.5) | 87 (26.1) | 0.004 |

Abbreviations: APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; SALRTI, severe acute lower respiratory tract infection; SD, standard deviation.

Data is presented as no. (%) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Values in brackets represent SD.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.2. Spectrum of respiratory viruses

Overall, 326 (49.5%) samples were positive for at least one respiratory virus, and there were 36 (5.5%) cases of viral coinfections. The groups of viruses identified were as follows, in descending order of prevalence: IFV (n = 94, 14.3%), RSV (n = 75, 11.4%), HRV (n = 56, 8.5%), ADV (n = 55, 8.3%), PIV (n = 47, 7.1%), HCoV (n = 15, 2.3%), HMPV (n = 14, 2.1%), and HBoV (n = 11, 1.7%).

3.3. Impact of sex and age on virus detection

The positive rates of viral infections in male and female patients were 48.44% (202 of 417) and 51.2% (124 of 242), respectively. No significant difference was found between both sexes (χ 2 = 0.480, P = 0.489). The positive rate in younger children (< 5 years) was significantly higher than that in older children (> 5 years) (52.5% vs 35.1%, χ 2 = 11.405, P = 0.001). Children aged 2 months to 1 year were the most susceptible to viral respiratory pathogens with a positive rate of 55.4% (Table 3). However, the infection patterns of viruses were different among the age groups. RSV was highly clustered in patients with SALRTI who are younger than 3 years old (> 10% positive rate). ADV accounted for 2.9% to 11.9% of the viruses identified in all age groups. This group of viruses was the common pathogen in all but with higher incidence in school‐aged children (5‐10 years old) in which IFV was the most frequent one (25.7%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of samples tested, positivity rates and viral findings by gender, season and age group

| Infections | Gender group (%) a | Age group (%) a | Seasonality (%) a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male [n = 417] | Female [n = 242] | 2 mo‐1 y [n = 240] | 1‐3 y [n = 160] | 3‐5 y [n = 145] | 5‐10 y [n = 70] | 10‐14 y [n = 44] | Spring [n = 203] | Summer [n = 157] | Autumn [n = 154] | winter [n = 145] | |

| Any viral etiology | 202 (48.4) | 124 (51.2) | 133 (55.4) | 87 (54.4) | 66 (45.5) | 27 (38.6) | 13 (29.5) | 111 (54.7) | 77 (49.0) | 67 (43.5) | 71 (49.0) |

| ADV | 33 (7.9) | 22 (9.1) | 13 (5.4) | 19 (11.9) | 16 (11.0) | 2 (2.9) | 5 (11.4) | 20 (9.9) | 13 (8.3) | 12 (7.8) | 10 (6.9) |

| HMPV | 7 (1.7) | 7 (2.9) | 6 (2.5) | 7 (4.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (5.9) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| IFV | 57 (13.7) | 37(15.3) | 22 (9.1) | 25 (15.6) | 26 (17.9) | 18 (25.7) | 3 (6.8) | 35 (17.2) | 14 (8.9) | 7 (4.5) | 38 (26.2) |

| RSV | 45 (10.8) | 30 (12.4) | 54 (22.5) | 17 (10.6) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.5) | 33 (16.3) | 16 (10.2) | 15 (9.7) | 11 (7.6) |

| HCoV | 11 (2.6) | 4 (1.7) | 7 (2.9) | 5 (3.1) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 5 (2.5) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.6) | 3 (2.1) |

| HRV | 41 (9.8) | 15 (6.2) | 30 (12.5) | 12 (7.5) | 8 (5.5) | 3 (4.3) | 3 (6.8) | 10 (4.9) | 16 (10.2) | 21 (13.6) | 9 (6.2) |

| PIV | 29 (7.0) | 18 (7.4) | 20 (8.3) | 10 (6.3) | 14 (9.7) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (2.3) | 8 (3.9) | 18 (11.5) | 15 (9.7) | 6 (4.1) |

| HBoV | 9 (2.2) | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.1) | 3 (1.9) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) | 6 (4.1) |

| Coinfections | 26 (6.2) | 10 (4.1) | 19 (7.9) | 11 (6.9) | 5 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 11 (5.4) | 9 (5.7) | 7 (4.5) | 9 (6.2) |

| Negative | 215 (51.6) | 118 (48.8) | 107 (44.6) | 73 (45.6) | 79 (54.5) | 43 (61.4) | 31 (70.5) | 92 (45.3) | 80 (51.0) | 87 (56.5) | 74 (51.0) |

Abbreviations: ADV, adenovirus; HBoV, human bocavirus; HCoV, human coronavirus; HMPV, human metapneumovirus; HRV, human rhinovirus; IFV, influenza virus; PIV, parainfluenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Data is presented as no. (%) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.4. Seasonality

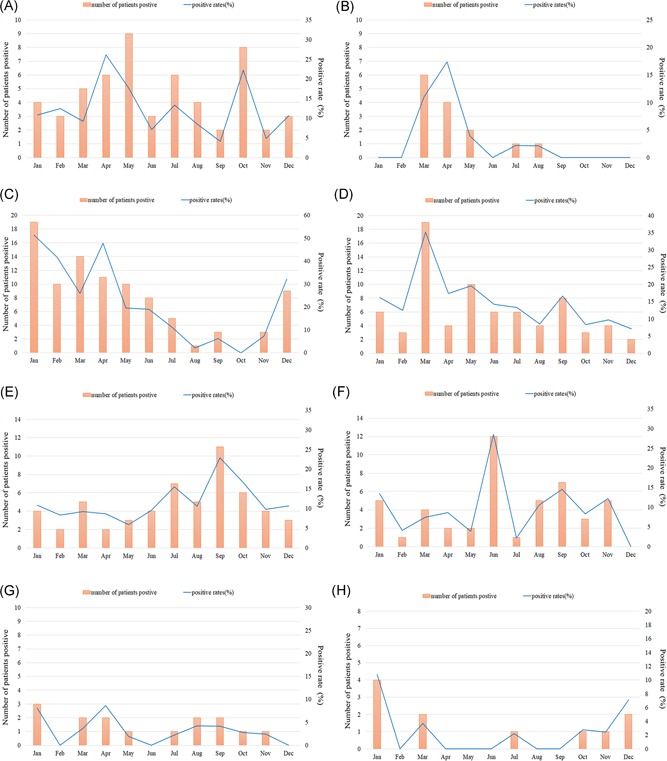

The patients were divided into four groups, in accordance with the seasons: (1) spring group (March, April, and May), 203 cases; (2) summer group (June, July, and August), 157 cases; (3) autumn group (September, October, and November), 154 cases; and (4) winter group (December, January, and February), 145 cases (Table 2). In general, the total frequency of positive tests for viruses was slightly higher in spring than in autumn (χ 2 = 4.373, P = 0.037), but no significant difference was observed between summer and winter (P > 0.05) (Table 3). However, different viruses varied significantly in terms of the monthly cumulative results. IFV exhibited remarkable seasonal distributions. Peaks in IFV detection lasted from winter to early spring, with a positive rate of 51.4% (19 of 37) in January and 47.8% (11 of 23) in April. RSV and HMPV were more frequently detected in spring, PIV in summer, and HRV in autumn. ADV was detected almost throughout the year, peaking in April and October (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Monthly cumulative distribution of eight categories respiratory viral targets from 659 children with severe acute lower respiratory tract infection in Guangzhou from May 2015 to April 2018. Virus‐positive patient number of monthly cumulative results and the monthly detection rate (% of monthly detected cases) were shown. A, adenovirus (ADV); B, human metapneumovirus (HMPV); C, influenza virus (IFV); D, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); E, human rhinovirus (HRV); F, parainfluenza virus (PIV); G, human coronavirus (HCoV); and H, human bocavirus (HBoV)

3.5. Clinical profiles associated with respiratory tract viral infection

The most common symptoms associated with viral SALRTI were cough (95.1%), fever (≥ 38.0º = °C) (92.9%), difficulty breathing (71.8%), and sputum production (67.5%). Compared with negative cases, more patients were observed to have a runny nose, sputum, tachypnea, difficulty breathing, and wheezing (all P < 0.05) (Table 2). The clinical characteristics of patients with the four main respiratory viral infections are summarized in Table 4. Among critically ill patients with IFV infection, fever (98.9%) was the most common symptom, but rales were not obvious compared with negative cases (55.3% vs 72.1%, P = 0.002). A significantly higher number of children had a runny nose (65.3%), difficulty breathing (66.7%), and increased rales (85.3%) in RSV infection than in IFV infection. More importantly, 25.3% of the children developed heart failure complications (all P < 0.05). Runny nose and sore throat were more prevalent among HRV‐infected patients (67.9% and 25.0%, respectively) than among virus‐negative patients (18.9% and 5.4%, respectively). There were statistically significant differences in the prevalence of sputum production, tachypnea, difficulty breathing, wheezing, pulmonary rales, and radiographic evidence of pneumonia according to whether a patient was infected by ADV or negative (all P < 0.05). Higher APACHE II scores were found in patients infected with RSV or ADV than in those infected with HRV, and more mechanical ventilation strategies were adopted in ADV‐infected cases (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the clinical characteristics between four major viral infections in SALRTI

| Characteristics | Negative (%) * | IFV (%) * | RSV (%) * | HRV (%) * | ADV (%) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [n = 333] | [N = 94] | [n = 75] | [n = 56] | [n = 55] | |

| Clinical history and physical examination | |||||

| T ≥ 38.0°C | 319 (95.8) | 93 (98.9) | 65 (86.7)a,b | 48 (85.7)a,b | 54 (98.2) |

| Cough | 320 (96.1) | 88 (93.6) | 72 (96.0) | 51 (91.1) | 54 (98.2) |

| Runny nose | 63 (18.9) | 12 (12.8) | 49 (65.3)a,b | 38 (67.9)a,b | 6 (10.9)c,d |

| Sore throat | 18 (5.4) | 11 (11.7) | 3 (4.0) | 14 (25.0)a,c | 6 (10.9) |

| Sputum production | 184 (55.3) | 54 (57.4) | 41 (54.7) | 32 (57.1) | 40 (72.7) |

| Tachypnea | 104 (31.2) | 31 (33.0) | 31 (41.3) | 21 (37.5) | 36 (65.5) a,b,d |

| Difficulty breathing | 177 (53.2) | 41 (43.6) | 50 (66.7)b | 28 (50.0) | 42 (76.4) a,b,d |

| Wheezing | 59 (17.7) | 19 (20.2) | 58 (77.3)a,b | 27 (48.2)a,b,c | 31 (56.4)a,b |

| Radiographic evidence of pneumonia | 255 (76.6) | 74 (78.7) | 47 (62.7) | 36 (64.3) | 49 (89.1)c,d |

| Lung rale sounds on auscultation | 240 (72.1) | 52 (55.3)a | 64 (85.3)b | 38 (67.9) | 29 (52.7)a,c |

| Comorbid conditions | |||||

| Asthma | 9 (2.7) | 6 (6.4) | 8 (10.6)a | 6 (10.7)a | 4 (7.3) |

| Heart failure | 16 (4.8) | 5 (5.3) | 19 (25.3)a,b | 1 (1.8)c | 6 (10.9)c |

| Hematological disease | 31 (9.3) | 11 (11.7) | 8 (10.7) | 9 (16.1) | 3 (5.5) |

| Neuromuscular disease | 2 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Autoimmune disease | 19 (5.7) | 4 (4.3) | 6 (8.0) | 5 (8.9) | 3 (5.5) |

| Immunosuppression | 60 (18.0) | 16 (17.0) | 15 (20.0) | 19 (33.9) | 6 (10.9)d |

| APACHE II score mean (SD) | 13.9 (3.9) | 14.8 (4.1) | 15.2 (4.6)a | 13.3 (3.7)c | 15.3(5.0)a,d |

| Presenting clinical manifestations | |||||

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation | 78 (23.4) | 26 (27.7) | 32 (42.7)a | 8 (14.3)b,c | 15 (27.3) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 86 (25.8) | 37 (39.4) | 18 (24.0) | 13 (23.2) | 32 (58.2)a,c,d |

| Vasoactive drugs | 88 (26.4) | 29 (30.9) | 20 (26.7) | 4 (7.1) | 21 (38.2) |

| Continuous venovenous hemofiltration | 11 (3.3) | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.5) |

| Corticoids | 87 (26.1) | 29 (30.9) | 43 (57.3)a,b | 7 (12.5)c | 18 (32.7) |

Note: a: P < 0.05 compared with Negative group; b: P < 0.05 compared with IFV‐positive group; c: P < 0.05 compared with RSV‐positive group; d: P < 0.05 compared with HRV‐positive group.

Abbreviations: ADV, adenovirus; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; HRV, human rhinovirus; IFV, influenza virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SALRTI, severe acute lower respiratory tract infection; SD, standard deviation.

Data is presented as no. (%) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, a thorough investigation of respiratory viruses was conducted in children with SALRTI who were admitted to the PICU in Guangzhou, China. The prevalence of eight categories of respiratory viruses and the clinical profiles of the four most common viral types (IFV, RSV, HRV, and ADV) were analyzed. Among the 659 samples, 326 (49.5%) contained at least one type of virus; this value was also observed in other studies conducted in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) in other areas (24.6%‐54.6%).17, 18, 19 This suggests that the respiratory tract virus, a major cause of SALRTI resulting in global human morbidity and mortality, warrants national awareness for its detection and management.

Among the viruses detected in PICU patients with SALRTI, IFV was the most prevalent. Multiple reports have described the clinical features of IFV infection, and the spectrum of clinical presentation varies from self‐limiting respiratory tract illness to primary viral pneumonia that ultimately leads to respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress, multiorgan failure, and even death.17, 20 Interestingly, IFV viruses were found to exhibit remarkable seasonal distributions, with their peaks lasting from winter to early spring, which is similar to the findings in another report.19 Most of the critically ill children were school aged. Moreover, 39.4% of the total infected patients required mechanical ventilation. These findings justified the need to maximize measures for preventing the spread of infection during epidemic periods and to implement active screening of influenza cases among the susceptible population.

In addition, RSV was identified to be the second prevalent virus type in children with SALRTI, consistent with the finding in other reports from developed and developing countries.18, 21 When children are hospitalized for RSV infection, they require inpatient resources at a very high rate. An investigation undertaken by a UK group demonstrated that RSV accounted for 15.6% of all admissions to intensive therapy units due to respiratory disease.22 The findings of this study showed that RSV was the leading viral pathogen identified in infants less than 1 year of age who are admitted in the PICU for SALRTI with a higher APACHE II score than that of virus‐negative cases, suggesting that RSV could be associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. This study also demonstrated that RSV infection occurred throughout the year, exhibiting a clear seasonal trend. RSV infection peaked in March, later than that in other published reports showing that RSV infection occurred most frequently in temperate regions during the winter months.23 This discrepancy may have resulted from the typical subtropical monsoon climate in Guangzhou, where March was considered an early beginning of spring.

In humans, HRV causes not only respiratory tract infection, including the most common cold but also severe respiratory illness such as pneumonia and bronchiolitis in children.24 HRV was the third most frequently detected respiratory virus type in the present study. HRV isolates were detected each month of the year, and the highest positive rates were in September. This result was consistent with that of a previous study in Suzhou,25 but different from that of a study in Changsha.26 The possible explanation for this difference was that the predominant species of HRV varies from location to location and year to year. A few distinct clinical characteristics were observed when different groups of patients were compared. HRV infection was more common than virus‐negative cases with a runny nose, throat sore, and wheezing and more prevalent in children with concurrent asthma and immunosuppression. Similar data were reported in other studies, highlighting that HRV frequently exacerbates pre‐existing airway diseases such as asthma.27 This may help inform clinicians of the strategies for the prevention and management of chronic diseases.

ADV was a significant cause of SALRTI, which continue to bring clinical challenges in terms of diagnostics and treatment.28 During the study period, 8.3% (55 of 659) of patients with ADV infection were detected, consistent with the findings of a previous study showing that ADV accounts for 5% to 10% of acute respiratory tract infection in children.29 It mostly affected children under the age of 5 (48 of 55), and the clinical features and disease progression in these cases are highly similar to those of acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by ADV in a previous report.30 Nearly all patients presented with fever (98.3%) and cough (98.3%). However, compared with virus‐negative cases, more children presented with sputum production, tachypnea, difficulty breathing, and wheezing. A previous study showed that the respiratory rate was an independent risk marker for in‐hospital mortality in community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) caused by ADV infection.31 The APACHE II score, one of the most commonly used severity assessment tools for critically ill patients, also provides important prognostic information for ADV in SALRTI. The clinical course of admitted patients in this study showed a substantial proportion of severe illness with higher APACHE II scores in patients, requiring a greater number of therapeutic interventions such as mechanical ventilation (58.2%) during their ICU stay. Radiography could be helpful in the early diagnosis of ADV pneumonia even when lung rales were not evident on auscultation. Severe ADV pneumonia has been frequently described in immunocompromised patients.28 Respiratory infection caused by ADV in immunocompetent patients was usually thought to be mild and self‐limited.32 However, 89.1% (49 of 55) of ADV infection cases in this study were immunocompetent. With advancements in modern molecular techniques, ADV has been increasingly found to be involved in sporadic cases and outbreaks of severe CAP in healthy individuals,33, 34 thus warranting attention from clinicians.

Several limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the study results. First, this study was conducted at a single center, which might lead to the underestimation of the overall detection rate for the selected viruses. Second, despite testing for a large panel of respiratory viruses, bacterial infection was not evaluated due to the difficulty in obtaining adequate samples for culture. Nevertheless, the role of bacterial pathogens in the development of SALRTI symptoms was taken into consideration.35 Further studies will thus be required to clarify their roles in SALRTI. Third, it should be considered that some respiratory viruses can be shed for long periods of time after infection or detection in asymptomatic children.36 Hence, the investigation of respiratory specimens from asymptomatic children would make the role of these viruses in SALRTI clearer.

In summary, despite the aforementioned limitations, this 3‐year surveillance provides a basic profile of the spectrum, seasonality, age, and sex distribution as well as the clinical association of viral respiratory infections in the PICU at the medical center where the study was conducted. This profile would be useful in the examination of viruses as well as the development of novel strategies in managing viral infections in SALRTI.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate Professor Bo Peng for proofing our manuscript. We are most grateful to the clinicians and nurses for their assistance in sample collection. This study was supported by the National Mega Project on Major Infectious Disease Prevention (grant number 2017ZX10103011), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81470219), Science and Technology Projects Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant number 2014A020212120) and the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat‐Sen University, Clinical Research Program (grant number QHJH201803).

Li Y‐T, Liang Y, Ling Y‐S, Duan M‐Q, Pan L, Chen Z‐G. The spectrum of viral pathogens in children with severe acute lower respiratory tract infection: A 3‐year prospective study in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Med Virol. 2019;91:1633‐1642. 10.1002/jmv.25502

References

REFERENCES

- 1. Kassebaum N, Kyu HH, Zoeckler L, et al. Child and adolescent health from 1990 to 2015: findings from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors 2015 Study. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017;171(6):573‐592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Disease GBD, Injury I. Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990‐2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211‐1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McAllister DA, Liu L, Shi T, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of pneumonia morbidity and mortality in children younger than 5 years between 2000 and 2015: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2019;7(1):e47‐e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nair H, Simoes EA, Rudan I, et al. Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1380‐1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095‐2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Global, regional, and national age‐sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980‐2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 . Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151‐1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rudan I, O'Brien KL, Nair H, et al. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia in 2010: estimates of incidence, severe morbidity, mortality, underlying risk factors and causative pathogens for 192 countries. J Glob Health. 2013;3(1):010401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tregoning JS, Schwarze J. Respiratory viral infections in infants: causes, clinical symptoms, virology, and immunology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):74‐98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gootz TD. The global problem of antibiotic resistance. Crit Rev Immunol. 2010;30(1):79‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization WHO Recommended Surveillance Standards , 2nd ed. WHO; 1999. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/surveillance/WHO_CDS_CSR_ISR_99_2_EN/en. Accessed April 12, 2014.

- 11. World Health Organization Handbook: IMCI Integrated Management of Childhood Illness . WHO; 2005. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241546441.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2014.

- 12. Zhang SF, Tuo JL, Huang XB, et al. Epidemiology characteristics of human coronaviruses in patients with respiratory infection symptoms and phylogenetic analysis of HCoV‐OC43 during 2010‐2015 in Guangzhou. PLOS One. 2018;13(1):e0191789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yu J, Jing H, Lai S, et al. Etiology of diarrhea among children under the age five in China: results from a five‐year surveillance. J Infect. 2015;71(1):19‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang D, He Z, Xu L, et al. Epidemiology characteristics of respiratory viruses found in children and adults with respiratory tract infections in southern China. Jiangsu Med J. 2014;25:159‐164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wen Kuan L, Qian L, De Hui C, et al. Epidemiology of acute respiratory infections in children in Guangzhou: a three‐year study. PLOS One. 2014;9(5):e96674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lin X, Xia H, Ding‐Mei Z, et al. Surveillance and genome analysis of human bocavirus in patients with respiratory infection in Guangzhou, China. PLOS One. 2012;7(9):e44876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piralla A, Mariani B, Rovida F, Baldanti F. Frequency of respiratory viruses among patients admitted to 26 Intensive Care Units in seven consecutive winter‐spring seasons (2009‐2016) in Northern Italy. J Clin Virol. 2017;92:48‐51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Visseaux B, Burdet C, Voiriot G, et al. Prevalence of respiratory viruses among adults, by season, age, respiratory tract region and type of medical unit in Paris, France, from 2011 to 2016. PLOS One. 2017;12(7):e0180888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu W, Guo L, Dong X, et al. Detection of viruses and mycoplasma pneumoniae in hospitalized patients with severe acute respiratory infection in Northern China, 2015‐2016. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2018;71:134‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alvarez‐Lerma F, Marin‐Corral J, Vila C, et al. Characteristics of patients with hospital‐acquired influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus admitted to the intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2017;95(2):200‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guerrier G, Goyet S, Chheng ET, et al. Acute viral lower respiratory tract infections in Cambodian children: clinical and epidemiologic characteristics. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(1):e8‐e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gaunt ER, Harvala H, Mcintyre C, Templeton KE, Simmonds P. Disease burden of the most commonly detected respiratory viruses in hospitalized patients calculated using the disability adjusted life year (DALY) model. J Clin Virol. 2011;52(3):215‐221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feng L, Li Z, Zhao S, et al. Viral etiologies of hospitalized acute lower respiratory infection patients in China, 2009‐2013. PLOS One. 2014;9(6):e99419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Greenberg SB. Update on human rhinovirus and coronavirus infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;37(4):555‐571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yan Y, Huang L, Wang M, et al. Clinical and epidemiological profiles including meteorological factors of low respiratory tract infection due to human rhinovirus in hospitalized children. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zeng SZ, Xiao NG, Xie ZP, et al. Prevalence of human rhinovirus in children admitted to hospital with acute lower respiratory tract infections in Changsha, China. J Med Virol. 2014;86(11):1983‐1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. SK L, CC Y, HW T, et al. Clinical features and complete genome characterization of a distinct human rhinovirus (HRV) genetic cluster, probably representing a previously undetected HRV species, HRV‐C, associated with acute respiratory illness in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(11):3655‐3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lion T. Adenovirus infections in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(3):441‐462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bezerra PG, Britto MC, Correia JB, et al. Viral and atypical bacterial detection in acute respiratory infection in children under five years. PLOS One. 2011;6(4):e18928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang SY, Luo YP, Huang DD, et al. Fatal pneumonia cases caused by human adenovirus 55 in immunocompetent adults. Infect Diseases. 2016;48(1):40‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Strauß R, Ewig S, Richter K, König T, Heller G, Bauer TT. The prognostic significance of respiratory rate in patients with pneumonia: a retrospective analysis of data from 705,928 hospitalized patients in Germany from 2010‐2012. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(29‐30):503‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tan D, Zhu H, Fu Y, et al. Severe community‐acquired pneumonia caused by human adenovirus in immunocompetent adults: a multicenter case series. PLOS One. 2016;11(3):e0151199‐e0151199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun B, He H, Wang Z, et al. Emergent severe acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by adenovirus type 55 in immunocompetent adults in 2013: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cassir N, Hraiech S, Nougairede A, Zandotti C, Fournier PE, Papazian L. Outbreak of adenovirus type 1 severe pneumonia in a French intensive care unit, September‐October 2012. Euro Surveillance. 2014;19(39):20914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Qu JX, Gu L, Pu ZH, et al. Viral etiology of community‐acquired pneumonia among adolescents and adults with mild or moderate severity and its relation to age and severity. BMC Infect Diseases. 2015;15(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Feikin DR, M Kariuki N, Godfrey B, et al. Viral and bacterial causes of severe acute respiratory illness among children aged less than 5 years in a high malaria prevalence area of western Kenya, 2007‐2010. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(1):14‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]