Abstract

Background

Out-of-hours (OOH) health care services are often divided into emergency medical services (EMS) and OOH primary care (OOH-PC). EMS and many OOH-PC use telephone triage, yet the patient still makes the initial choice of contacting a service and which service. Sociodemographic characteristics are associated with help-seeking. Yet, differences in characteristics for EMS and OOH-PC patients have not been investigated in any large-scale cohort studies. Such knowledge may contribute to organizing OOH services to match patient needs. Thus, in this study we aimed to explore which sociodemographic patient characteristics were associated with utilizing OOH health care and to explore which sociodemographic characteristics were associated with EMS or OOH-PC contact.

Methods

A population-based observational cohort study of inhabitants in two regions (North Denmark Region and Capital Region of Copenhagen) with or without contact to OOH services during 2016 was conducted. Associations between sociodemographic characteristics and OOH contacts (and EMS versus OOH-PC contact) were evaluated by regression analyses.

Results

We identified 619,857 patients with OOH contact. Female sex (IRR=1.16 (95% CI: 1.16–1.17)), non-western ethnicity (IRR=1.02 (95% CI: 1.01–1.02)), living alone (IRR=1.08 (95% CI: 1.08–1.09)), age groups ≥81 years (IRR=2.00 (95% CI: 1.98–2.02)) and 0–18 years (IRR=1.66 (95% CI: 1.66–1.67)) and low income (IRR=1.41 (95% CI: 1.40–1.42)) were more likely to contact OOH health care compared to males, Danish ethnicity, citizens cohabitating, age 31–65 years and high income. Disability pensioners more often contacted OOH care (IRR=1.79 (95% CI: 1.77–1.81) compared to employees. Old age (≥81 years) (OR=3.21 (95% CI: 3.13–3.30)), receiving cash benefits (OR=2.45 (95% CI: 2.36–2.54)), low income (OR=1.76 (95% CI: 1.72–1.81)) and living alone (OR=1.40 (95% CI: 1.37–1.42)) were all associated with EMS contacts rather than OOH-PC contacts.

Conclusion

Several sociodemographic factors were associated with contacting a health care service outside office hours and with contacting EMS rather than OOH-PC. Old age, low income, low education and low socioeconomic status were of greatest importance.

Keywords: out-of-hours health care, delivery of health care, Denmark, telephone hotline, telephone triage

Background

In several countries, patients in need of acute health care outside office hours can contact two types of services; emergency medical services (EMS) in life- or limb-threatening situations or out-of-hours primary care (OOH-PC) for less urgent injuries or diseases. Even though the EMS and many OOH-PC services use telephone triage to assess the most adequate response to the patient’s condition, the patient or bystander makes the initial choice of contacting a service and which service to contact.1–3 So far, studies on patient characteristics associated with contacting an acute health care setting have either included patients contacting EMS or OOH-PC and mostly focus has been on inappropriate or recurrent use.4–8 However, possible overlaps in the EMS and OOH-PC patient populations have been observed; some patients in need of acute care contact OOH-PC and some patients with non-specific complaints perhaps more suitable for OOH-PC contact EMS.9–12 Besides the patient’s self-perceived urgency and severity of the acute health problem, other factors play a role in the choice of entrance to out-of-hours (OOH) care. A number of studies have found that sociodemographic characteristics such as low education, ethnicity and older age and factors regarding the health-care system itself (organization of access to primary care) were associated with help-seeking, but no large-scale cohort studies have investigated differences in these characteristics for patients contacting EMS and OOH-PC.13–15

Concurrently, all OOH services are experiencing an increasing demand and workload, emphasizing the importance of understanding patient help-seeking behavior and the development in contact patterns with these services.16,17 More insight into sociodemographic characteristics associated with seeking OOH health care and choosing one service over the other could contribute to the understanding of patient utilization of OOH health care service. Ultimately, this may contribute to organizing the out-of-hours services to match patient needs.

Thus, in this study we aimed to explore which sociodemographic patient characteristics were associated with utilizing OOH health care and secondly, to explore which sociodemographic characteristics were associated with EMS or OOH-PC contact.

Methods

Design and Study Population

A population-based observational cohort study of inhabitants in two Danish regions (ie North Denmark Region and Capital Region of Copenhagen) with or without contact to OOH services (EMS and OOH-PC) during 2016 was conducted. The two regions were chosen to include all types of services existing in Denmark, varying in size, population density, sociodemographic profile and available health care services.18 We only included citizens with a valid personal identification number (PIN) and residence in the same region as the OOH service investigated.19 We followed the STROBE guidelines when reporting our results.20

Setting

The North Denmark Region is a rural-urban region with 586,000 inhabitants, with the EMS and the general practitioner cooperatives (GPC) as OOH services.21 GPs operate the GPC and through telephone triage, they assess what the patient is in need of; telephone advice, consultation, home visit, or a direct referral to the hospital.22 The Capital Region of Copenhagen is primarily urban and home to 1,789,000 inhabitants, with the Medical Helpline 1813 (MH-1813) available alongside EMS as OOH services.21 Nurses handle the majority of calls at the MH-1813, together with physicians of different medical specialties. They perform triage by systematically using a computerized decision support tool to decide whether the patient is in need of telephone advice, a clinic consultation, a home visit, or a direct referral to the hospital. MH-1813 carry out home visits, whereas the clinic consultations take place in hospital emergency departments.23 As well as answering direct calls, the physicians also act as consultants for the nurses. Both GPC and MH-1813 were considered OOH-PC services in this study. EMS is organized in a similar fashion in the two regions (as in all five Danish regions). Each region has an Emergency Medical Coordination Centre (EMCC), which is part of the EMS. Calls to the national emergency number 1-1-2 concerning acute health problems are redirected to EMCC, where the nurses/paramedics use a criteria-based dispatch protocol to assess the level of urgency and the most adequate response.1,2 We considered OOH as 4 P.M to 8 A.M on workdays and all hours on weekends and public holidays (GPC hours). Danish health care is tax-financed and free of charge, including the EMS and OOH-PC services.

Variables and Data Sources

Exposure

We defined each sociodemographic characteristic as the exposure in the present study (eg belonging to a specific age or socioeconomic classification group). The included sociodemographic variables were chosen based on existing literature reporting the importance of age, sex, ethnicity, family type, education level, income and socioeconomic classification (labor market affiliation) in relation to health care utilization.5,13,15,24–27 We used each citizen’s unique PIN for linkage to numerous registries and databases. Age (divided into five groups), sex, residence, family type (collapsed into cohabiting or living alone) and ethnicity (Danish, Western, non-western) were gathered from the Civil Registration System.19 Education level was based on Danish education registers covering compulsory schooling to university-level education and training.28 We used the highest completed education and collapsed the data into three categories based on education length. Income quartiles were computed based on each citizen’s available income obtained through registers on personal income.29 Socioeconomic classification is based on Danish registers on labor market affiliation and contains data on type of employment, unemployment, benefits, pension, etc.30

Outcome Measures

We defined our primary outcomes as 1) ratio of OOH contacts given a sociodemographic variable compared to a reference and 2) likelihood of contacting EMS or OOH-PC for each sociodemographic variable. EMS and OOH-PC service contacts were identified in the prehospital databases (containing data on time of contact and information from the prehospital medical records) and in the National Health Service Registry.31

Statistical Analysis

Data were anonymized prior to analysis. Descriptive statistics were used for reporting the prevalence of sociodemographic characteristics by region and by contact type. As a citizen may have had contact to more than one OOH service, we identified the OOH service first contacted during the study period and assigned this citizen to this service when describing and comparing the groups.

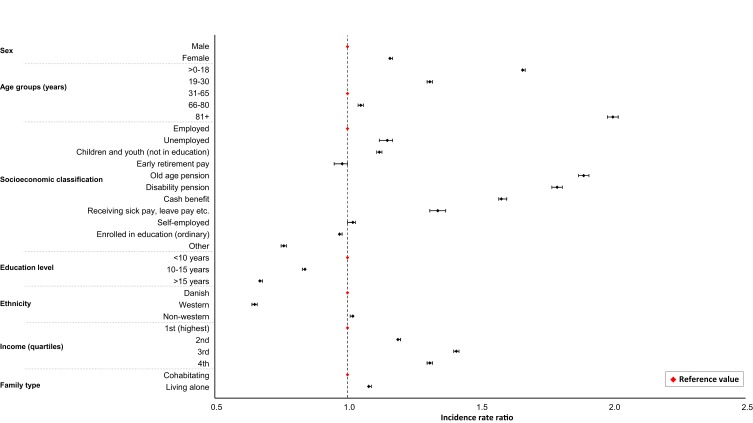

To explore which sociodemographic characteristics were associated with utilizing OOH health care as rates, we performed negative binomial regression analysis (with the Huber-White sandwich estimator to achieve robust estimates) between each sociodemographic characteristic and contact rate, yielding incidence rate ratios (IRR) (eg the ratio of contacts for females with males as the reference).32 All IRRs were shown combined in a forest plot.

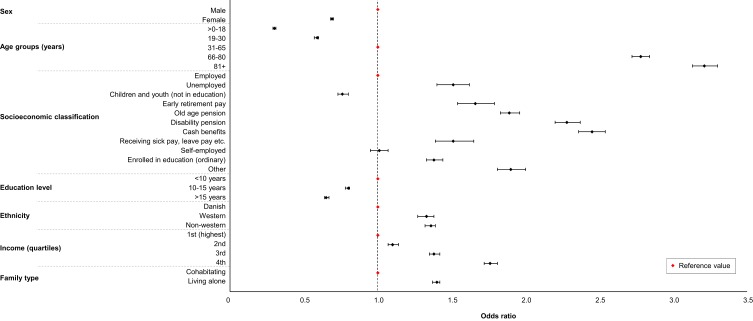

To explore which sociodemographic characteristics were associated with contact to EMS or OOH-PC, we performed logistic regression analyses yielding odds ratios (OR) estimates for EMS or OOH-PC contact as outcome, also shown in a forest plot. For this analysis, we also used the OOH service first contacted for assigning citizens to either EMS or OOH-PC. Additionally, we performed a sensitivity analysis including citizens by the OOH service most frequently contacted (Table S1).

All regression analyses were adjusted for age (continuous) and sex, when possible. Results presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI) or standard deviations (SD), when relevant. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata V.15.0/MP (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (North Denmark Region record number 2008-58-0028 and project identification number 2017–171) and use of information from the prehospital medical records was approved by the Danish Patient Safety Authority (record number 3-3013-2315/1).

Results

We identified 619,857 (26.1%) patients with at least one OOH service contact, while 1,754,816 (73.9%) citizens had no contacts during 2016 (Table 1). The majority (89.3%) of contacts were to OOH-PC. The characteristics of all included citizens are shown separated by contact type in Table 1 and by region in Table S2.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics Separated by Contact Type, N= 2,374,673

| Type of Contact | No Contact | EMS | OOH-PC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (per 1000 inhabitants) | 1,754,816 (739) | 66,508 (28) | 553,349 (223) | 2,374,673 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 888,444 (374) | 34,531 (15) | 250,348 (105) | 1,173,323 |

| Female | 866,372 (365) | 31,977 (13) | 303,001 (128) | 1,201,350 |

| Age Groups (years) | ||||

| 0–18 | 327,000 (138) | 6,470 (3) | 168,774 (71) | 502,244 |

| 19–30 | 295,558 (124) | 7,808 (3) | 108,057 (46) | 411,423 |

| 31–65 | 842,621 (355) | 24,874 (10) | 200,051 (84) | 1,067,546 |

| 66–80 | 240,167 (101) | 17,387 (7) | 50,419 (21) | 307,973 |

| 81+ | 49,470 (21) | 9,969 (4) | 26,048 (11) | 85,487 |

| Socioeconomic Classification | ||||

| Unemployed | 21,695 (9) | 798 (0) | 6,330 (3) | 28,823 |

| Children and youth (not in education) | 252,397 (106) | 4,112 (2) | 140,343 (59) | 396,852 |

| Early retirement pay | 24,461 (10) | 879 (0) | 3,878 (2) | 29,218 |

| Old-age pension | 270,180 (114) | 26,663 (11) | 73,349 (31) | 370,192 |

| Disability pension | 47,411 (20) | 4,762 (2) | 19,378 (8) | 71,551 |

| Cash benefits | 47,667 (20) | 4,145 (2) | 20,824 (9) | 72,636 |

| Employed | 757,909 (319) | 16,435 (7) | 189,495 (80) | 963,839 |

| Receiving sick pay, leave pay, etc. | 13,722 (8) | 627 (0) | 5,602 (2) | 19,951 |

| Self-employed | 55,150 (23) | 1,340 (1) | 12,441 (5) | 68,931 |

| Enrolled in education (ordinary) | 191,016 (80) | 4,833 (2) | 67,163 (28) | 263,012 |

| Other | 73,066 (31) | 1,911 (1) | 14,523 (6) | 89,500 |

| Missing | 142 (0) | 3 (0) | 23 (0) | 168 |

| Income (Quartiles) | ||||

| First (highest) | 469,112 (192) | 10,579 (4) | 113,977 (48) | 593,668 |

| Second | 442,189 (186) | 12,763 (5) | 138,716 (58) | 593,668 |

| Third | 419,515 (177) | 21,597 (9) | 152,555 (64) | 593,667 |

| Fourth (lowest) | 424,000 (179) | 21,569 (9) | 148,101 (62) | 593,670 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Danish | 1,472,096 (620) | 56,591 (24) | 472,779 (199) | 2,001,466 |

| Western countries | 107,587 (45) | 2,963 (1) | 19,657 (8) | 130,207 |

| Non-Western countries | 175,133 (74) | 6,954 (3) | 60,913 (26) | 243,000 |

| Family Type | ||||

| Living alone | 626,019 (264) | 33,646 (14) | 199,012 (84) | 858,677 |

| Cohabitating | 1,128,797 (475) | 32,862 (14) | 354,337 (149) | 1,515,996 |

| Education Level (Years) | ||||

| <10 | 396,202 (167) | 23,732 (10) | 138,762 (58) | 558,696 |

| 10–15 | 557,970 (235) | 22,917 (10) | 155,982 (66) | 736,869 |

| >15 | 509,329 (212) | 13,189 (6) | 114,113 (48) | 636,631 |

| Missing | 291,315 (123) | 6,670 (3) | 144,492 (61) | 442,477 |

Characteristics Associated with Contacting Any OOH Service

Age, Sex and Ethnicity

The oldest age group (81+ years) had the highest likelihood of contacting OOH care of all age groups (IRR=2.00 (95% CI: 1.98–2.02)), followed by children (0–18 years) and young adults (19–30 years) compared to the age group 31–65 years (Figure 1, Table S3). Females were more likely to have a contact to OOH care than males (IRR=1.16 (95% CI: 1.16–1.17)). With Danish origin as the reference, citizens from other Western countries were less likely to contact OOH care (IRR=0.65 (95% CI: 0.64–0.66)), while non-westerners had more contacts (IRR=1.02 (95% CI: 1.01–1.02)).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of the ratio of contact rates for each sociodemographic variable, adjusted IRR 95% CI, N=2,374,673.

Notes: Missing values in variables education level (151,162) and socioeconomic classification (168); thus analyses only included 1,932,196 and 2,374,505 individuals for the two variables.

Education, Income and Family Type

A clear tendency was observed for education; with higher education level, contacts to OOH care were fewer, eg education level >15 years (IRR=0.67 (95% CI: 0.67–0.68)) compared to an education level of <10 years (Figure 1, Table S3). Income level displayed an almost similar tendency; with the first (highest) income quartile as reference, all lower quartiles were more likely to have contacts to OOH care. Patients living alone more often had contacts than those cohabiting (IRR=1.08 (95% CI: 1.08–1.09)).

Socioeconomic Classification

When having an employment was defined as the reference for socioeconomic classification, old age pensioners had the highest likelihood of contacting OOH care (IRR=1.89 (95% CI: 1.87–1.91)), followed by disability pensioners, patients on cash benefits and on sick pay, leave pay, etc. (Figure 1, Table S3).

Characteristics Associated with Contacting EMS and OOH-PC

Age, Sex and Ethnicity

Compared to 31–65 years as reference, the odds for an EMS contact were higher in the older age groups 66–80 years (OR=2.78 (95% CI: 2.72–2.84)) and 81+ years (OR=3.21 (95% CI: 3.13–3.30)). The remaining age groups (0–18, 19–30 years) were more likely to contact OOH-PC (Figure 2, Table S4). With men as the reference, women (OR=0.69 (95% CI: 0.68–0.70)) were less likely to have an EMS contact. Both patients of Western and non-western origin had higher odds for EMS contact than those of Danish origin (OR=1.33 (95% CI: 1.27–1.38)) and 1.36 (1.32–1.39).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the association between sociodemographic variables and adjusted odds ratios for EMS vs OOH-PC, OR 95% CI, N=619,857.

Notes: Missing values in variables education level (151,162) and socioeconomic classification (26); thus analyses only included 468,695 and 619,831 individuals for the two variables.

Education, Income and Family Type

Citizens with an education level of 10–15 and >15 years were less likely to have an EMS contact (OR=0.80 (95% CI: 0.78–0.81) and 0.65 (0.64–0.67)), when comparing to an education level of <10 years (Figure 2, Table S4). With the highest income level as the reference, odds for EMS contact increased with decreasing income level; hence, fourth income quartile (lowest) had the highest odds (OR=1.76 (95% CI: 1.72–1.81)). Patients living alone were also more likely to contact EMS than those cohabiting (OR=1.40 (95% CI: 1.37–1.42)).

Socioeconomic Classification

Patients in the socioeconomic classification groups; cash benefits, disability pension, other, old age pension, early retirement pay, receiving sick pay, etc., unemployed and enrolled in education (ordinary) all had higher likelihood of EMS contact (in that descending order) with odds ranging from OR=2.45 (95% CI: 2.36–2.54) to 1.38 (1.33–1.44) when compared to those in employment (Figure 2, Table S4). The socioeconomic group of children and youth (not in education) was less likely to contact EMS (OR=0.76 (95% CI: 0.73–0.80)) than those in employment.

Discussion

Main Findings

In this large cohort study, we found that citizens with the characteristics female sex, non-western ethnicity and living alone were significantly more likely to contact OOH health care compared to males, Danish ethnicity and citizens cohabitating. Furthermore, the oldest and youngest age groups more frequently had OOH contacts. With lower education and lower income, the likelihood of any OOH contact increased. Additionally, receiving disability pension, old age pension and cash benefits were highly associated with any form of OOH health care contact. Old age, receiving cash benefits or disability pension, lower income and living alone were all associated with having a contact to EMS rather than OOH-PC as well.

Strengths and Limitations

A notable study strength was the population-based study design, including all contacts to OOH health care, as Danish health care (and OOH services) is freely accessible for all, thus minimizing selection bias and resulting in a very large cohort. Each citizen’s unique PIN allowed us to identify most of the citizens who had OOH health care contacts and to link the contact to important sociodemographic variables. Additionally, by including these particular two Danish regions, the study included all types of OOH health care services available in Denmark.

Assigning patients to groups using the first contact during the study period may have introduced a bias in our estimates, since the same patients could have a different type of OOH service later on. However, our sensitivity analysis with citizens assigned to the OOH service they contacted most frequently during the study period only minimally changed our results, but not our message (Table S1) as the distribution of contacts to EMS and OOH-PC was similar despite changing the inclusion method. The large difference in size of the EMS and OOH-PC group (10% versus 90% of included contacts) could have skewed the results towards variables associated with OOH-PC contact, when exploring variables associated with any OOH contact. For the exposure variable education level, there was a large number of missing values (18.6%, predominately children without any completed education yet), not equally distributed between having an OOH contact or not nor between the OOH-PC and EMS groups. Thus, in the groups with fewest missing values (no OOH contact and EMS contact), the association between education level and contacts may have been overestimated and correspondingly underestimated in the groups with most missing values. Lastly, missing PINs is a known issue in EMS contacts, especially those of low urgency. A previous Danish study has reported that around 18% of EMS contacts have missing PINs.10 If contacts without registered PINs comprise a patient group with certain sociodemographic characteristics, this may affect our estimates.

Comparison with Literature

Most studies investigating the association between sociodemographic characteristics and contacts to OOH health care have investigated either EMS or OOH-PC, rarely both services at once. A survey study on OOH help-seeking used hypothetical case scenarios and investigated the intended behavior (not contacting OOH care vs contacting OOH care (=EMS, OOH-PC or emergency department)) of each case scenario. Although using a different methodology, they found older age, female sex, ethnicity, low education and low income to be associated with OOH care contact, which is supported by our study.13 Another larger survey study including data from 34 countries investigated the propensity to seek health care (GP during daytime) and found that older age, female sex, ethnicity (first-generation migrants) were predisposing factors for seeking health care.14 Although the study investigated GP contact during daytime, their findings are in good agreement with our findings for OOH care. We found only one cohort study comparing factors associated with contacting EMS versus OOH-PC. Moll van Charante et al investigated differences in patient characteristics for contacts to the GPC and EMS outside office hours and found male sex and higher age to be more frequent among EMS users, also in accordance with our results.33 Other studies have predominately focused on factors related to EMS use solely, where especially factors such as male gender, older age, low income and low socioeconomic status are emphasized.25,27 We found similar factors to be associated with EMS use compared to OOH-PC.

Recommendations and Future Research

Low income, low education level and low socioeconomic status were associated with OOH care and EMS contacts in this study. It is not unlikely that these characteristics may also be associated with comorbidity/chronic disease. Other studies have shown that sociodemographic characteristics such as low education level is associated with higher all-cause mortality and low socioeconomic status with a higher degree of multi-morbidity.34,35 Such characteristics are then likely surrogate measures for underlying health issues. However, not only health issues affect the choice of contacting an OOH service and the level of health literacy in our population may be an important factor to investigate. To explore if there is potential for preventive interventions, it could be beneficial to investigate to what extent both comorbidity and health literacy are associated with contacts to OOH care in our population. Moreover, availability or accessibility to primary care (ie GPs) may influence the use of OOH care, and in future studies, it should be considered.36,37

Conclusion

In this large cohort study, we have identified sociodemographic characteristics associated with contacting a health care service outside office hours and with contacting EMS rather than OOH-PC. Old age, low income, low education and low socioeconomic status were of greatest importance.

Abbreviations

EMS, emergency medical services; OOH-PC, out-of-hours primary care; OOH, out-of-hours; PIN, personal identification number; STROBE, STrengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology; GPC, general practitioner cooperative; GP, general practitioner; MH-1813; Medical Helpline 1813; EMCC, emergency medical coordination centre; IRR, incidence rate ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals; SD, standard deviation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank data managers Kaare Rud Flarup, Flemming Bøgh Jensen, Martin Vang Rasmussen and Mikkel Dahlstrøm Jørgensen for their help with obtaining data for the study and statisticians Niels Henrik Bruun and Torben Anders Kløjgaard as well as PhD Fellow Tim Alex Lindskou for their advice regarding the study.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the North Denmark Region and the Capital Region of Copenhagen, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license from the Danish Patient Safety Authority for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Author Contributions

MBS, EFC, MBC, LH, HCC and BHB co-conceived the research. MBS performed the analysis. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

EFC holds a professorship supported by a grant given by the philanthropic foundation TrygFonden to Aalborg University. MBS received a grant from the philanthropic foundation Helsefonden. MBC and LH received a grant given by the philanthropic foundation TrygFonden. The grants do not restrict any scientific research and the funding body had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing of the manuscript. The authors report no other competing interests.

References

- 1.Lindskou TA, Mikkelsen S, Christensen EF, et al. The Danish prehospital emergency healthcare system and research possibilities. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019;27(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s13049-019-0676-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen MS, Johnsen SP, Sørensen JN, Jepsen SB, Hansen JB, Christensen EF. Implementing a nationwide criteria-based emergency medical dispatch system: a register-based follow-up study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21(1):53. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-21-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huibers L, Giesen P, Wensing M, Grol R. Out-of-hours care in western countries: assessment of different organizational models. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):105. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Søvsø MB, Kløjgaard TA, Hansen PA, Christensen EF. Repeated ambulance use is associated with chronic diseases - a population-based historic cohort study of patients’ symptoms and diagnoses. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019;27(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s13049-019-0624-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carret MLV, Fassa ACG, Domingues MR. Inappropriate use of emergency services: a systematic review of prevalence and associated factors. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25(1):7–28. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2009000100002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caplan SE, Straus JH. Strategies for reducing inappropriate after-hours telephone calls. Clinical Pediatr. 1988;27(5):236–239. doi: 10.1177/000992288802700504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nørøxe KB, Huibers L, Moth G, Vedsted P. Medical appropriateness of adult calls to Danish out-of-hours primary care: a questionnaire-based survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0617-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott J, Strickland AP, Warner K, Dawson P. Frequent callers to and users of emergency medical systems: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(8):684–691. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booker MJ, Simmonds RL, Purdy S. Patients who call emergency ambulances for primary care problems: a qualitative study of the decision-making process. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(6):448–452. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-202124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen EF, Larsen TM, Jensen FB, et al. Diagnosis and mortality in prehospital emergency patients transported to hospital: a population-based and registry-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011558. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehm KK, Andersen MS, Riddervold IS. Non-urgent emergency callers: characteristics and prognosis. Prehospital Emerg Care. 2017;21(2):166–173. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2016.1218981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Søvsø MB, Christensen MB, Bech BH, Christensen HC, Christensen EF, Huibers L. Contacting out-of-hours primary care or emergency medical services for time-critical conditions - impact on patient outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):813. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4674-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keizer E, Christensen MB, Carlsen AH, et al. Factors related to out-of-hours help-seeking for acute health problems: a survey study using case scenarios. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6332-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Loenen T, van den Berg MJ, Faber MJ, Westert GP. Propensity to seek healthcare in different healthcare systems: analysis of patient data in 34 countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):465. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1119-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huibers L, Keizer E, Carlsen AH, et al. Help-seeking behaviour outside office hours in Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland: a questionnaire study exploring responses to hypothetical cases. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e019295. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowthian JA, Cameron PA, Stoelwinder JU, et al. Increasing utilisation of emergency ambulances. Aust Heal Rev. 2011;35(1):63. doi: 10.1071/AH09866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huibers LA, Moth G, Bondevik GT, et al. Diagnostic scope in out-of-hours primary care services in eight European countries: an observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henriksen DP, Rasmussen L, Hansen MR, Hallas J, Pottegård A. Comparison of the five Danish regions regarding demographic characteristics, healthcare utilization, and medication use—a descriptive cross-sectional study. Dalal Ked. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):22–25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statistics Denmark. Danmarks Statistik [Statistics Denmark]. Available from: http://www.statistikbanken.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1440. Accessed January 14, 2020.

- 22.Olesen F, Jolleys JV. Out of hours service: the Danish solution examined. BMJ. 1994;309(6969):1624–1626. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6969.1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebert JF, Huibers L, Christensen B, Lippert FK, Christensen MB. Giving callers the option to bypass the telephone waiting line in out-of-hours services: a comparative intervention study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(1):120–127. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2019.1569427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philips H, Remmen R, De Paepe P, Buylaert W, Van Royen P. Out of hours care: a profile analysis of patients attending the emergency department and the general practitioner on call. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11(1):88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawakami C, Ohshige K, Kubota K, Tochikubo O. Influence of socioeconomic factors on medically unnecessary ambulance calls. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):120. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen R, Newman JF, Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Heal Soc. 1973;51(1):95–124. doi: 10.2307/3349613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rucker DW, Edwards RA, Burstin HR, O’Neil AC, Brennan TA. Patient-specific predictors of ambulance use. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29(4):484–491. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70221-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):91–94. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):103–105. doi: 10.1177/1403494811405098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, Thygesen LC. Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):95–98. doi: 10.1177/1403494811408483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahl Andersen J, De Fine Olivarius N, Krasnik A. The Danish National Health Service Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):34–37. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moll van Charante EP, van Steenwijk-opdam PC, Bindels PJE. Out-of-hours demand for GP care and emergency services: patients‘ choices and referrals by general practitioners and ambulance services. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ullits LR, Ejlskov L, Mortensen RN, et al. Socioeconomic inequality and mortality - a regional Danish cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):490. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1813-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLean G, Gunn J, Wyke S, et al. The influence of socioeconomic deprivation on multimorbidity at different ages: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(624):e440–e447. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X680545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cecil E, Bottle A, Cowling TE, Majeed A, Wolfe I, Saxena S. Primary care access, emergency department visits, and unplanned short hospitalizations in the UK. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20151492–e20151492. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin A, Martin C, Martin PB, Martin PA, Green G, Eldridge S. ’Inappropriate’ attendance at an accident and emergency department by adults registered in local general practices: how is it related to their use of primary care? J Heal Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(3):160–165. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Statistics Denmark. Danmarks Statistik [Statistics Denmark]. Available from: http://www.statistikbanken.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1440. Accessed January 14, 2020.