Animals harbor bacterial symbionts with specific traits that promote host fitness. Mechanisms that facilitate intercellular interactions among bacterial symbionts impact which bacterial lineages ultimately establish symbiosis with the host. How these mechanisms are regulated is poorly characterized in nonhuman bacterial symbionts. This study establishes a model for the transcriptional regulation of a contact-dependent killing machine, thereby increasing understanding of mechanisms by which different strains compete while establishing symbiosis.

KEYWORDS: Vibrio fischeri, cell-cell interaction, invertebrate-microbe interactions, secretion systems, sigma factors, symbiosis, transcriptional regulation

ABSTRACT

Vibrio fischeri is a bacterial symbiont that colonizes the light organ of the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes. Certain strains of V. fischeri express a type VI secretion system (T6SS), which delivers effectors into neighboring cells that result in their death. Strains that are susceptible to the T6SS fail to establish symbiosis with a T6SS-positive strain within the same location of the squid light organ, which is a phenomenon termed strain incompatibility. This study investigates the regulation of the T6SS in V. fischeri strain FQ-A001. Here, we report that the expression of Hcp, a necessary structural component of the T6SS, depends on the alternative sigma factor σ54 and the bacterial enhancer binding protein VasH. VasH is necessary for FQ-A001 to kill other strains, suggesting that VasH-dependent regulation is essential for the T6SS of V. fischeri to affect intercellular interactions. In addition, this study demonstrates VasH-dependent transcription of hcp within host-associated populations of FQ-A001, suggesting that the T6SS is expressed within the host environment. Together, these findings establish a model for transcriptional control of hcp in V. fischeri within the squid light organ, thereby increasing understanding of how the T6SS is regulated during symbiosis.

IMPORTANCE Animals harbor bacterial symbionts with specific traits that promote host fitness. Mechanisms that facilitate intercellular interactions among bacterial symbionts impact which bacterial lineages ultimately establish symbiosis with the host. How these mechanisms are regulated is poorly characterized in nonhuman bacterial symbionts. This study establishes a model for the transcriptional regulation of a contact-dependent killing machine, thereby increasing understanding of mechanisms by which different strains compete while establishing symbiosis.

INTRODUCTION

Most animals form symbioses with specific bacteria that exhibit traits that promote normal host physiology and behavior (1–4). Many of these bacterial symbionts are acquired from the environment, which can result in multiple cells colonizing the same host tissue. Certain bacteria have evolved to express molecular mechanisms that antagonize other cells, which is significant because these mechanisms can alter which bacteria ultimately establish symbiosis (5–7). One such mechanism is the type VI secretion system (T6SS), which is a contact-dependent, toxin delivery system (8). While the T6SS was initially described as a virulence factor in pathogenic bacteria (9, 10), subsequent studies have established that T6SSs also mediate antagonistic microbe-microbe interactions (6–8). T6SS-dependent killing occurs between different bacterial species (7) and between different bacterial strains (11, 12). Consequently, T6SSs are a major factor in determining the composition of bacterial symbionts within host microbiomes (13).

The T6SS is comprised of 13 core components that resemble a phage tail (10). The structural core components assemble as a transmembrane complex, which includes a baseplate that anchors the apparatus to the cell (14) and a tail complex that forms a syringe-like structure (15). The inner tube portion of the tail complex is comprised of haemolysin coregulated protein (Hcp), which assembles as a stack of hexameric rings (8, 10). Hcp was one of the first core components identified, and it is vital for structural integrity of the complex (10), is secreted into the surrounding milieu (10, 16), and associates with toxic effectors (17). Because of the multiple roles Hcp has in T6SSs, understanding the mechanisms regulating expression of this component provides insight into how T6SS is expressed.

This study investigates a T6SS in the context of the symbiosis between the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, and bioluminescent Vibrio fischeri bacteria (18). Adult squid use the bioluminescence of V. fischeri to camouflage themselves at night (19). The symbiosis is initially established in juvenile squid, with V. fischeri colonizing a specialized organ within the host called the light organ (18). The nascent light organ contains six epithelium-lined crypt spaces that serve as the colonization sites for V. fischeri (18). V. fischeri is the only species of bacteria that can colonize the crypt spaces of the light organ (20), and during initial colonization, a physical bottleneck permits entry into each crypt by only 1 or 2 cells (21). Proliferation of these founder cells results in light-emitting populations that fill each crypt space. Previous work found that squid that are exposed to the T6SS-positive strain FQ-A001 and the type strain ES114 do not exhibit crypt spaces with both strain types (21). This phenomenon, which we defined as strain incompatibility (14, 21), is due to the activity of a T6SS encoded by two gene clusters in FQ-A001 (14). Hcp proteins with 100% identity are encoded by two hcp genes, hcp and hcp1, which are located in the large T6SS gene cluster and the auxiliary T6SS gene cluster, respectively (14). Additionally, ectopic expression of either gene is sufficient to restore T6SS function in a Δhcp Δhcp1 mutant of V. fischeri (14), suggesting that transcriptional control of hcp genes is a potential mechanism for the bacteria to modulate T6SS expression.

Here, we report that the alternative sigma factor σ54 and the bacterial enhancer binding protein VasH activate the transcription of each hcp gene, thereby promoting the expression of the T6SS in FQ-A001. Both factors are necessary for T6SS-dependent effects, including killing ES114 on solid medium and FQ-A001/ES114 strain incompatibility in vivo. In addition, we show that VasH-dependent transcription of hcp occurs within the squid light organ, providing evidence that the crypt spaces are environments conducive for T6SS-dependent activities.

RESULTS

T6SS-dependent effects depend on σ54.

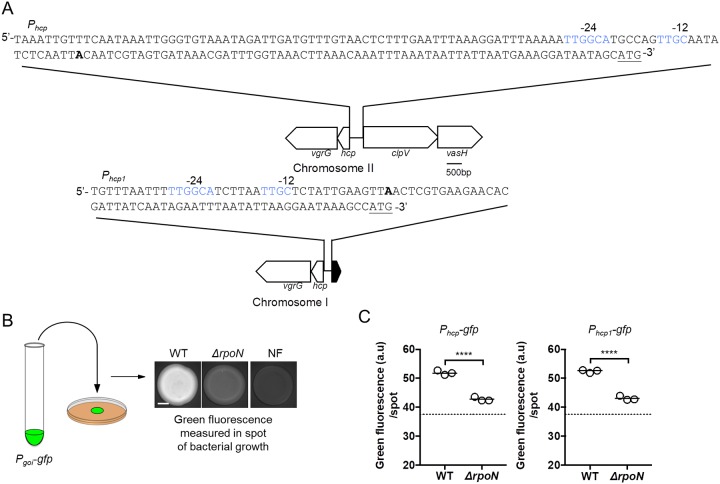

In V. fischeri, type VI secretion system (T6SS)-mediated effects depend on Hcp, which is encoded by either of the hcp genes in the T6SS-positive strain FQ-A001 (14). In V. cholerae, transcription of hcp genes depends on the alternative sigma factor σ54 (15, 22). In general, σ54-dependent promoters contain two motifs distal to the +1 transcriptional start site that are necessary for σ54-promoter interactions: TGC centered at bp −12 (−12 site) and TGGCA centered at bp −24 (−24 site) (23, 24). The promoter regions of hcp and hcp1 of FQ-A001 each exhibit canonical −12 and −24 sites (Fig. 1A), suggesting that the transcriptional expression of each hcp gene depends on σ54.

FIG 1.

Impact of σ54 on hcp and hcp1 expression. (A) Nucleic acid sequences for the hcp (top) and hcp1 (bottom) promoters. The bold “A” indicates the predicted transcriptional start site. Nucleic acids in blue indicate putative σ54 binding sequences (YTGGCACGrNNNTTGCW). Underlined nucleic acids indicate the start codon for Hcp. Schematic illustrates the genetic arrangement of hcp and hcp1 along with the intergenic regions upstream of each gene. The sequence for this intergenic region is shown above each gene cluster schematic. (B) Schematic of fluorescence-based reporter assay to evaluate gene expression. A culture of V. fischeri harboring a GFP reporter construct was used to generate a 2-μl cell suspension that was inoculated as a spot onto solid medium. After 24 h, the fluorescence of the resulting growth spot was imaged by microscopy. An isogenic, nonfluorescent (NF) control is used to determine background fluorescence. The scale bar indicates 1 mm. (C) Green fluorescence per spot of growth for indicated strains. The dashed line represents the autofluorescence of a nonfluorescent sample. Strains used in this experiment are FQ-A001 (WT) and KRG007 (ΔrpoN). The promoter tested in each experiment is indicated above the graph. pKRG001 (Phcp-gfp) and pNPW15 (Phcp1-gfp) were the reporter plasmids used in this experiment. Differences between groups were determined using a t test: ****, P < 0.0001. Results shown are from a representative trial of an experiment that was performed three times.

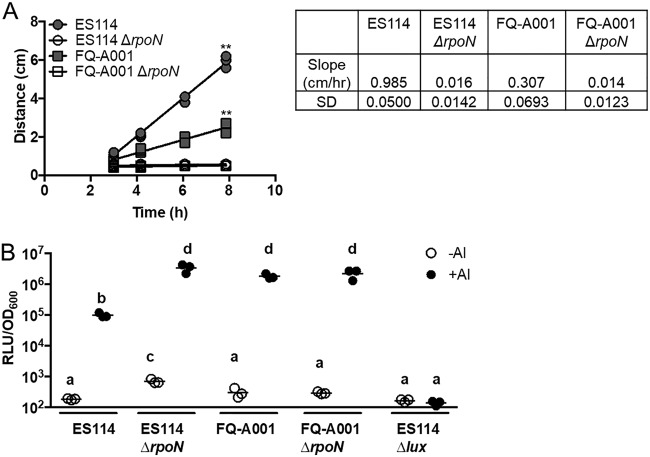

To test this hypothesis, we first generated a mutant of FQ-A001 by deleting the rpoN gene, which encodes σ54. Previous work with the classical strain ES114, which does not encode the T6SS of FQ-A001 (14), demonstrated that σ54 promotes motility and inhibits bioluminescence (25). To determine whether σ54 also impacts these traits in FQ-A001, the resulting mutant, ΔrpoN, was examined for motility and bioluminescence. The ΔrpoN mutant was nonmotile in soft agar (Fig. 2A), suggesting that, like in strain ES114 (22), σ54-dependent transcription is essential for motility in FQ-A001. However, the ΔrpoN mutant exhibited bioluminescence levels that did not differ from wild type (Fig. 2B), suggesting that σ54 does not impact bioluminescence in FQ-A001. Therefore, it appears that the gene-regulatory network that controls bioluminescence in FQ-A001 differs from that of ES114.

FIG 2.

Impact of σ54 on bacterial traits that promote symbiosis. (A) Measurements of bacterial motility ring diameter over time. Strains used in this experiment were FQ-A001, ES114, KRG003 (ES114 ΔrpoN), and KRG007 (FQ-A001 ΔrpoN). Linear regression was performed for each sample, and slopes determined to deviate from 0 are marked ** (P < 0.01). Motility rates are reported to the right of the plot along with their standard deviations (SD). (B) Bioluminescence levels of cells grown in the presence and absence of an autoinducer (AI). Strains used in this experiment were FQ-A001, ES114, KRG003 (ES114 ΔrpoN), KRG007 (FQ-A001 ΔrpoN), and EVS102 (ES114 Δlux). Differences between log-transformed groups were determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. Comparisons between groups with different letters have significantly different means (P < 0.05), while comparisons between groups with the same letter do not have significantly different means (P > 0.05). Results shown are from a representative trial of an experiment performed twice.

To quantify transcriptional expression of hcp, we cloned 474 bp of the hcp promoter upstream of gfp, resulting in a GFP-based reporter (Phcp-gfp). Because the exact location of the transcriptional start site has yet to be determined, the entire intergenic region upstream of hcp was included in the Phcp-gfp reporter (Fig. 1A). Expression of hcp was determined by quantifying the green fluorescence of bacteria that had grown on solid medium (Fig. 1B), which is an experimental condition that permits the contact-dependent interactions necessary for T6SS-dependent effects (14). Relative to wild type (WT), the ΔrpoN mutant containing the Phcp-gfp reporter exhibited lower levels of green fluorescence (Fig. 1C), suggesting that σ54 promotes expression of the hcp gene. A similar effect was observed with a GFP-based reporter containing 288 bp of the hcp1 promoter (Phcp1-gfp) (Fig. 1C), suggesting that σ54 activates expression of the hcp1 gene as well. Together, these data suggest that Hcp expression depends on σ54 in V. fischeri.

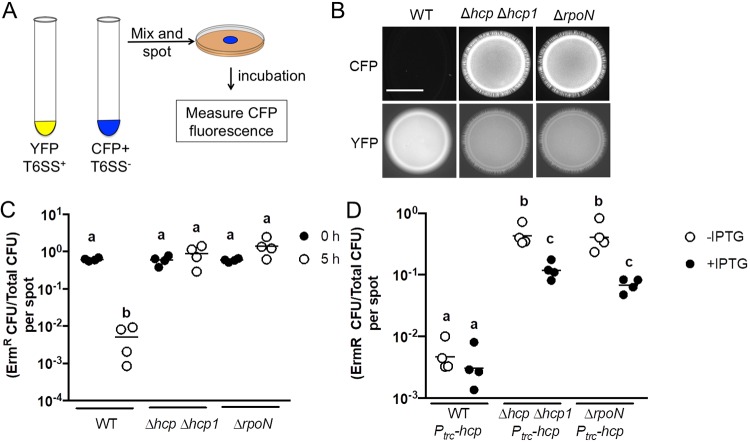

To determine whether σ54 impacts T6SS-dependent functions in V. fischeri, the ΔrpoN mutant was assessed for its ability to inhibit the growth of a different V. fischeri strain on solid medium. To distinguish between different strains in the assay, FQ-A001-derived strains were labeled with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), and ES114, which was the competitor strain for these assays, was labeled with cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) (Fig. 3A). Spots initiated with FQ-A001 and ES114 showed little CFP fluorescence after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 3B), suggesting that growth of ES114 was inhibited. In contrast, ES114 did grow within spots initiated with a Δhcp Δhcp1 mutant of FQ-A001 (Hcp−), suggesting that the growth inhibition of ES114 by FQ-A001 depends on T6SS, as reported previously (14). The spots of growth initiated with ΔrpoN also contained higher CFP levels relative to the WT control (Fig. 3B), suggesting that σ54-dependent transcription promotes the ability of FQ-A001 to inhibit ES114 growth. Additionally, the CFP fluorescence of spots with the ΔrpoN mutant was comparable to that of spots containing the Hcp− strain (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the effect of T6SS on growth inhibition depends strongly on σ54 in FQ-A001.

FIG 3.

Impact of σ54 on T6SS-dependent activities. (A) Schematic of coincubation assay for evaluating T6SS-dependent growth inhibition. (B) Images of blue fluorescence (top) and yellow fluorescence (bottom) from spots of bacterial growth resulting from mixtures of ES114 cells expressing CFP and the indicated FQ-A001-derived strain expressing YFP, incubated for 24 h. The scale bar indicates 5 mm. (C) Relative abundance of ES114 CFU and total CFU within mixtures at 0 h and 5 h postincubation. The y axis shows the ratio of erythromycin-resistant (Ermr) CFU to total CFU per mixture (spot). A two-way ANOVA revealed significant differences between log-transformed groups as a function of time. Sidak’s post hoc test was performed to statistically compare the means, with P values adjusted for multiple comparisons. Comparisons between groups with different letters have significantly different means (P < 0.0001), while comparisons between groups with the same letter do not have significantly different means (P > 0.05). (D) Ratio of Ermr CFU/total CFU resulting from a 5-h coincubation of an Ermr ES114 labeled Camr by the plasmid pYS112 mixed with the indicated FQ-A001-derived strains harboring a vector with hcp under the Ptrc promoter (Ptrc-hcp). Each point represents the ratio associated with an individual spot incubated in the absence of IPTG or in the presence of 1 mM IPTG, and each bar represents the geometric mean (n = 4). Two-way ANOVA revealed significant differences among the means of log-transformed ratios. Tukey’s post hoc test was performed to statistically compare the means, with P values adjusted for multiple comparisons. Comparisons between groups with different letters have significantly different means (P < 0.01), while comparisons between groups with the same letter do not have significantly different means (P > 0.05). Results shown are from a representative trial of an experiment that was performed twice.

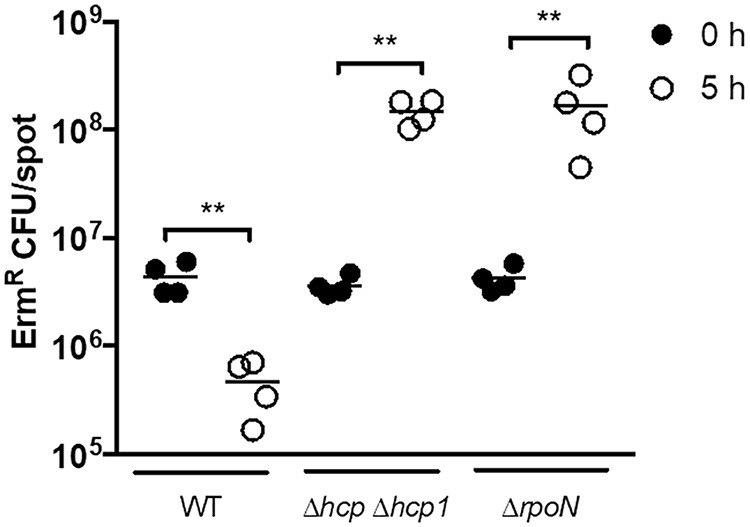

The inhibition of ES114 growth by FQ-A001 is attributed to the killing activity of the T6SS, which can be detected within the first 5 h of coincubation (11, 14). To determine whether σ54 impacts T6SS-dependent killing, the ΔrpoN mutant was assessed for its ability to kill ES114 using a modified version of the growth inhibition assay shown in Fig. 3A. FQ-A001-derived strains were combined with erythromycin-resistant (Ermr) ES114 and spotted onto solid medium. Spots containing mixtures of ES114 and FQ-A001 cells were evaluated for CFU at both the initial time point and after 5 h of coincubation. Results showed that after a 5-h incubation with WT FQ-A001, the relative abundance of Ermr cells within the spot had decreased (Fig. 3C), consistent with FQ-A001 killing ES114. In contrast, Ermr cells increased in relative abundance over time when incubated with the ΔrpoN mutant (Fig. 4), suggesting that σ54-dependent transcription promotes T6SS-dependent killing. To determine whether the effect of ΔrpoN on T6SS expression is due to lowered Hcp expression, we coincubated ES114 with a ΔrpoN mutant containing hcp under the control of the IPTG-inducible trc promoter (Ptrc-hcp). Relative to the vector control, induction of hcp in the ΔrpoN mutant resulted in decreased survival of ES114 (Fig. 3D), suggesting that σ54-dependent transcription of hcp promotes T6SS-dependent growth inhibition of ES114. Taken together, these results suggest that σ54-dependent transcription promotes T6SS-dependent activities in FQ-A001.

FIG 4.

Ermr ES114 CFU at 0 h and 5 h after coincubation with the indicated FQ-A001-derived strains. Strains used in this experiment were FQ-A001 (WT), KRG005 (Δhcp Δhcp1), and KRG007 (ΔrpoN). Each circle represents an individual biological sample. Comparisons of log-transformed ratios over time were evaluated using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison test; **, P < 0.01. Results shown are from a representative trial of an experiment performed twice.

σ54 is necessary for FQ-A001 to colonize E. scolopes.

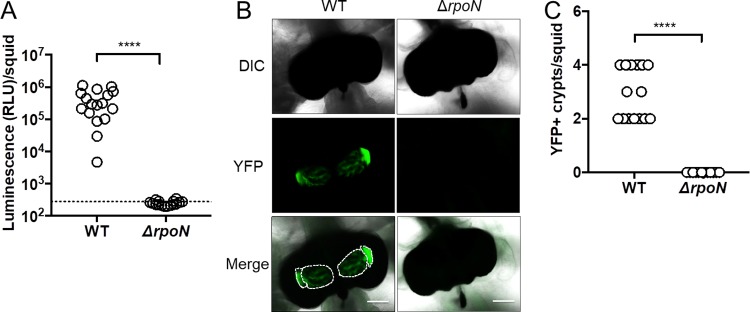

During initial colonization of the juvenile light organ in squid, more than one cell can enter each epithelium-lined crypt space within the host, which accounts for host-associated populations comprised of multiple strain types (26). However, FQ-A001 and ES114 are unable to occupy the same crypt space within established symbioses (21), and this strain incompatibility depends on Hcp expression by FQ-A001 (14). Based on the results with σ54 described above, we hypothesized that strain incompatibility also depends on σ54. However, animals exposed to a YFP-labeled ΔrpoN mutant remained dark (Fig. 5A), and their light organs did not harbor YFP fluorescence (Fig. 5B and C), suggesting that σ54 is necessary for FQ-A001 to colonize the juvenile light organ, which is analogous to the role played by σ54 in ES114 during symbiosis establishment (22).

FIG 5.

Impact of σ54 on symbiosis establishment by FQ-A001. (A) Luminescence per squid 48 h postinoculation with either FQ-A001 (WT) or KRG007 (ΔrpoN) harboring the YFP+ plasmid pSCV38. The dotted line indicates the 95% tail of luminescence associated with animals within an aposymbiotic group, above which animals are scored as luminescent. Differences between groups were determined using a Mann-Whitney test; ****, P < 0.0001. (B) Representative images of light organs from squid described for panel A. Colonized crypt spaces are outlined by a dotted line. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (C) Number of crypts spaces per squid in panel A that are positive for YFP fluorescence (YFP+). There were at least 15 animals in each group. Differences were determined by a Mann-Whitney test using the median YFP+ crypts per squid for animals within each group; ****, P < 0.0001. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. Results shown are from a representative trial of an experiment performed twice.

σ54-dependent expression of Hcp depends on VasH.

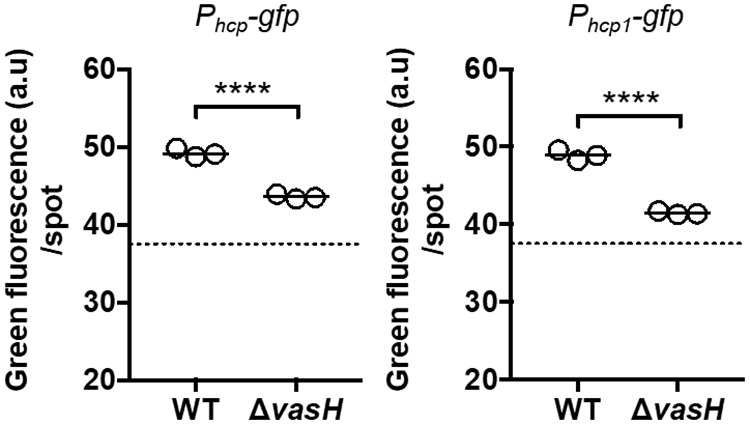

Because σ54 is necessary for FQ-A001 to colonize the squid (Fig. 5), the impact of σ54 on strain incompatibility in vivo could not be assessed using the ΔrpoN mutant. Transcription of a σ54-dependent promoter absolutely depends on a bacterial enhancer binding protein (bEBP), which recognizes specific sites upstream of the promoter and catalyzes open complex formation through ATP hydrolysis (24). In V. cholerae, σ54-dependent transcription of hcp genes is controlled by a bEBP called VasH that is encoded within the large T6SS gene cluster (15). The large T6SS gene cluster of FQ-A001 contains VFFQA001_15615 (28), which is predicted to encode a protein comprised of 534 amino acids that is 95% identical to VasH of V. cholerae (VCA0117) (15, 27). This homolog of VasH is one of 12 predicted bEBPs in FQ-A001 (28) and is not a member of the 10 predicted bEBPs encoded within the genome of ES114 (29), which is a T6SS-negative strain. Like VasH, VFFQA001_15615 is predicted to contain a GAF domain (residues 25 to 173), an AAA+ domain (residues 231 to 378), and an HTH domain (residues 380 to 533), which are associated with group III bEBPs (15). Therefore, we hypothesized that VFFQA001_15615 encodes the bEBP that promotes σ54-dependent expression of hcp and hcp1 in FQ-A001. To test this hypothesis, a 1.6-kb in-frame deletion of VFFQA001_15615 was introduced into FQ-A001 to generate a ΔvasH mutant, and the corresponding levels of hcp and hcp1 expression were measured using the spotting assay described above (Fig. 1B). For each promoter, GFP fluorescence was lower in the ΔvasH mutant relative to WT (Fig. 6), suggesting that VasH promotes transcription of the hcp genes. Together, these results suggest that Hcp expression depends on the bEBP VasH in FQ-A001.

FIG 6.

Impact of VasH on hcp and hcp1 expression. Green fluorescence per spot of growth was measured for the indicated strains. Strains used in this experiment were FQ-A001 (WT) and KRG005 (ΔvasH) harboring either the pKRG001 (Phcp-gfp) or the pNPW15 (Phcp1-gfp) reporter plasmid. The dotted line represents the autofluorescence of a nonfluorescent sample. The promoter being tested in each experiment is indicated above the graph. Statistical differences between groups were determined using a t test; ****, P < 0.0001. Results shown are representative of two independent experiments. Results shown are from a representative trial of an experiment that was performed three times.

T6SS-dependent effects depend on VasH.

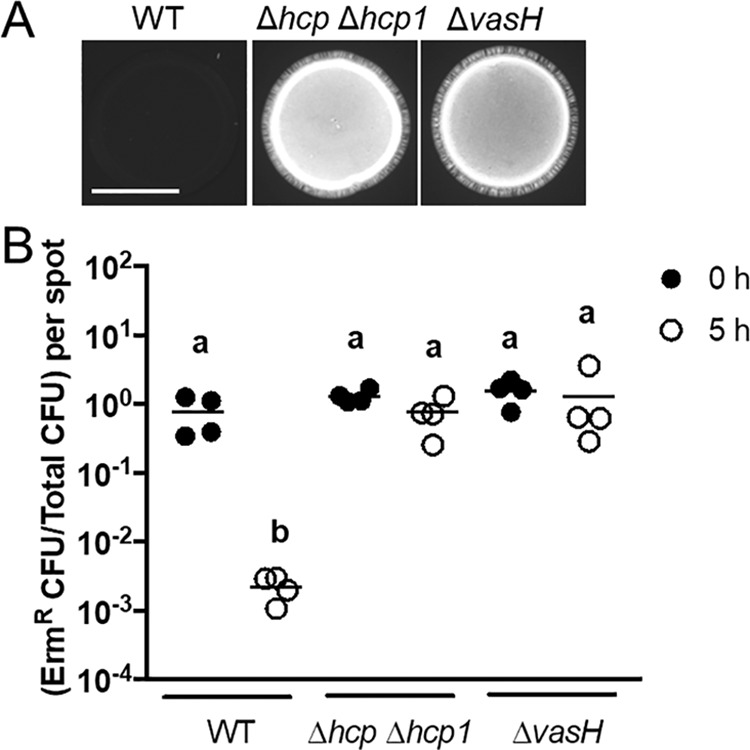

To determine whether VasH impacts T6SS-dependent activities in FQ-A001, the ΔvasH mutant was evaluated for its ability to inhibit the growth of ES114. Coincubation of ES114 with the ΔvasH mutant resulted in higher levels of CFP fluorescence relative to spots initiated with WT (Fig. 7A), which suggests that VasH promotes the ability of FQ-A001 to inhibit ES114 growth. In addition, the relative abundance of ES114 after 5 h of coincubation with the ΔvasH mutant was higher than the WT control (Fig. 7B), suggesting that VasH promotes T6SS-dependent killing by FQ-A001. Furthermore, the relative abundance of ES114 following coincubation with the ΔvasH mutant was comparable to the Hcp− control (Fig. 7B), suggesting a strong dependence of T6SS-dependent killing on VasH in FQ-A001. Finally, coincubation of ES114 and the ΔvasH mutant harboring a Ptrc-vasH in the presence of IPTG resulted in low CFP fluorescence (Fig. 8A), demonstrating genetic complementation with vasH expressed in trans. Together, these results suggest that T6SS-mediated effects depend greatly on VasH in V. fischeri.

FIG 7.

Impact of VasH on T6SS-mediated activities. (A) Images of blue fluorescence from spots of bacterial growth resulting from mixtures of ES114 cells expressing CFP and the indicated FQ-A001-derived strain. Strains used in this experiment were FQ-A001 (WT), NPW58 (Δhcp Δhcp1), and KRG005 (ΔvasH). The scale bar indicates 5 mm. (B) Cellular abundance of ES114 and FQ-A001 mixtures at 0 h and 5 h postincubation. The y axis shows the ratio of erythromycin-resistant (Ermr) CFU to total CFU per mixture (spot). A two-way ANOVA revealed significant differences between log-transformed group means as a function of time. Sidak’s post hoc test was performed to statistically compare the means, with P values adjusted for multiple comparisons. Comparisons between groups with different letters have significantly different medians (P < 0.0001), while comparisons between groups with the same letter do not have significantly different medians (P > 0.05). Results shown are from a representative trial of an experiment performed twice.

FIG 8.

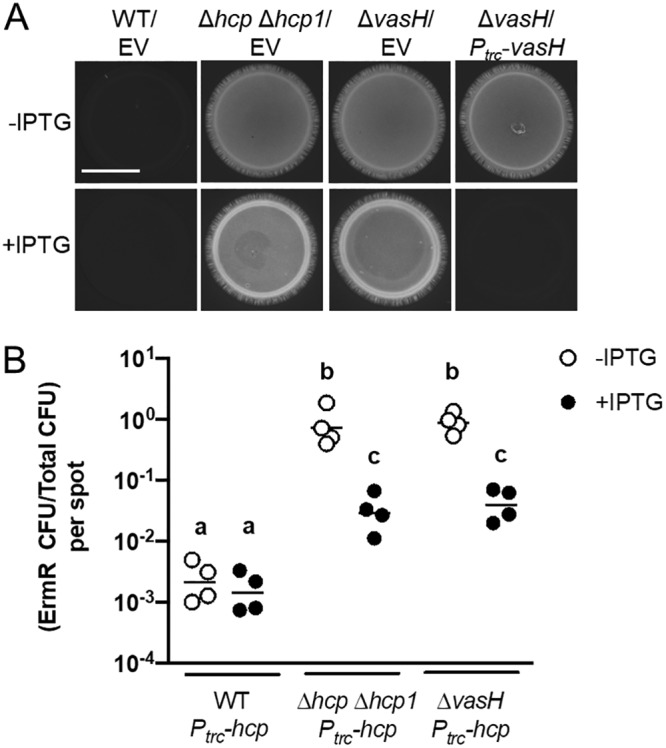

Impact of ΔvasH mutant complementation on T6SS-mediated activities. (A) Images of cyan fluorescence from mixtures of ES114 cells expressing CFP and FQ-A001-derived cells harboring either empty vector (EV) or pKRG028 (Ptrc-vasH). Strains used in this experiment were FQ-A001 (WT), NPW58 (Δhcp Δhcp1), and KRG005 (ΔvasH). The scale bar indicates 5 mm. (B) Ratio of Ermr CFU/Camr CFU resulting from 5-h coincubation of the Ermr ES114-derived strain TIM313 labeled Camr by the plasmid pYS112 with the indicated FQ-A001-derived strains. Each point represents the ratio associated with an individual spot at 5 h without IPTG or with 1 mM IPTG, and each bar represents the geometric mean (n = 4). Differences between log-transformed groups were determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. Comparisons between groups with different letters have significantly different medians (P < 0.0001), while comparisons between groups with the same letter do not have significantly different medians (P > 0.05). Results shown are from a representative trial of an experiment performed twice.

To determine whether the impact of VasH on T6SS-dependent effects depends on Hcp expression alone, we assessed how overexpression of Hcp in the ΔvasH mutant affects the growth of ES114. The ΔvasH mutant harboring the Ptrc-hcp construct was coincubated with ES114 in the presence and absence of 1 mM IPTG. After 5 h, the abundance of ES114 was slightly lower in the presence of IPTG (Fig. 8B), suggesting that the defect in growth inhibition by the ΔvasH mutant is due to lowered Hcp expression. This effect is similar to what was observed with the ΔrpoN mutant (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the transcriptional activation of hcp genes by VasH is necessary and sufficient for σ54-dependent inhibition of ES114 growth.

VasH-dependent transcription of hcp promotes strain incompatibility in the light organ.

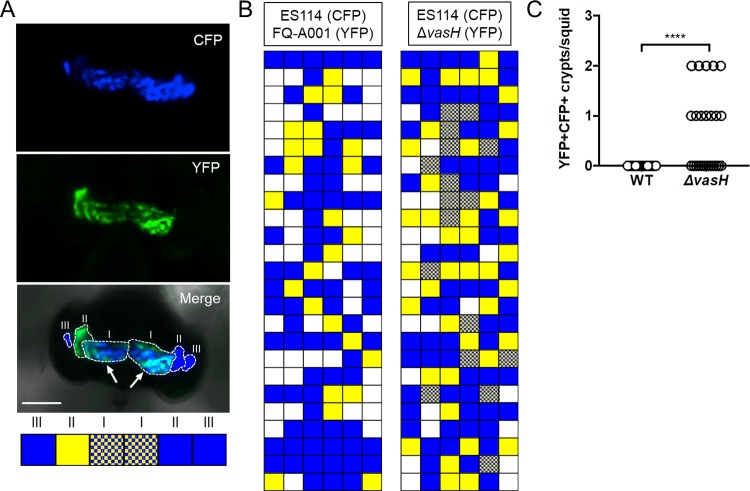

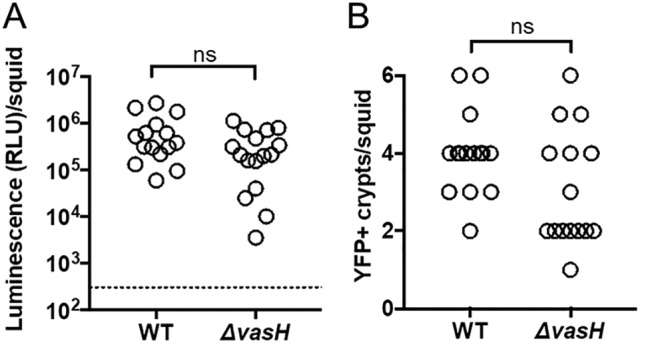

Squid exposed to the ΔvasH mutant exhibited normal luminescence and contained colonized crypts at frequencies comparable to the animals in the WT control group (Fig. 9), suggesting that symbiosis establishment by FQ-A001 is independent of VasH. To determine whether VasH impacts FQ-A001/ES114 strain incompatibility during symbiosis, juvenile squid were exposed to an inoculum mixed evenly with CFP-labeled ES114 and the YFP-labeled ΔvasH for 3.5 h. At 48 h postinoculation, their light organs were examined by fluorescence microscopy and each crypt space scored for YFP or CFP fluorescence (Fig. 10A). Consistent with previous reports (11, 14, 21), squid exposed to an inoculum containing differentially labeled ES114 and FQ-A001 failed to yield any cocolonized crypts (Fig. 10B and C), suggesting strain incompatibility between ES114 and FQ-A001. In contrast, the ES114/ΔvasH group had 12/25 animals (48%) exhibiting at least one crypt space containing both YFP and CFP fluorescence signals (Fig. 10B and C), suggesting that the ΔvasH mutant and ES114 could occupy the same crypt space. This result indicates that VasH promotes the T6SS-dependent strain incompatibility observed between ES114 and FQ-A001 during symbiosis.

FIG 9.

Impact of VasH and σ54 on symbiosis establishment. (A) Luminescence per squid 48 h postinoculation with either FQ-A001 (WT) or KRG005 (ΔvasH) expressing YFP. There are at least 15 animals per condition. Differences between groups were determined using a Mann-Whitney test; ns, P > 0.05. The dotted line indicates the threshold for luminescent animals, determined by a t test on luminescence values associated with aposymbiotic animals, above which animals are scored as luminescent. (B) Number of colonized crypts per squid. There are at least 16 animals in each group. Differences between groups were determined using a Mann-Whitney test; ns, P > 0.05. Results are from a representative trial from an experiment performed twice.

FIG 10.

Impact of VasH on strain incompatibility in vivo. (A) Representative image of a squid light organ showing colonized crypts outlined with a dashed line. Crypts were scored as being positive for YFP, CFP, or both YFP and CFP, as shown in boxes below the micrograph. Crypts are labeled I, II, or III on each side of the light organ. A cocolonized crypt (CFP+ YFP+) is highlighted by arrows. Strains used in this experiment were ES114, FQ-A001, and KRG005 (FQ-A001 ΔvasH). (B) Colonization states of colonized crypts for all animals exposed to the inoculum mixed with the indicated strains. White boxes indicate putative crypts that were not colonized. Each row represents an animal, and each box represents a potential crypt within that animal’s light organ. (C) Number of crypts exhibiting both YFP and CFP signal (YFP+ CFP+) per squid shown in panel B. Each symbol represents one animal within the indicated group. Differences between groups were determined by Mann-Whitney statistical analysis; ****, P < 0.0001. Results are from a representative trial of an experiment performed twice.

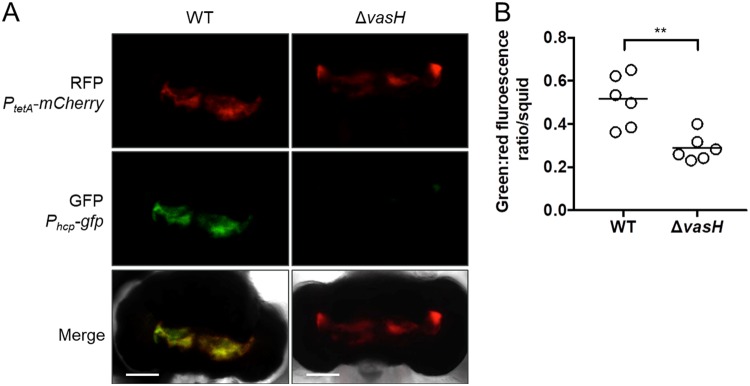

To determine whether VasH-dependent expression of hcp occurs in vivo, hcp promoter activity was measured in the animal using cells harboring the Phcp-gfp promoter reporter. In addition to the Phcp-gfp promoter fusion, the pKRG001 promoter reporter also contains a PtetA-mCherry promoter fusion. The tetA promoter is active in V. fischeri cells (30), providing mCherry as a marker for bacterial populations inside the light organ. Animals (n = 6 per group) were exposed to either WT FQ-A001 or the ΔvasH mutant harboring the Phcp-gfp plasmid. At 48 h postinoculation, animals were anesthetized and prepared for imaging of their light organs by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 11A). The corresponding GFP and mCherry fluorescence levels were quantified, and for each mCherry-positive pixel, the ratio of GFP/mCherry fluorescence was calculated and averaged across the light organ as a measure of hcp expression within host-associated bacteria. The average GFP/mCherry ratio per animal was lower in the ΔvasH mutant relative to WT populations (Fig. 11B), suggesting that within the host, FQ-A001 transcriptionally expresses hcp in a VasH-dependent manner. In addition, this result suggests that VasH is expressed and functions during symbiosis. Together, these findings suggest that VasH promotes T6SS-dependent strain incompatibility within the host.

FIG 11.

Impact of VasH on hcp expression in vivo. (A) Representative images of light organs colonized by either WT or ΔvasH, where the top shows red fluorescence, the middle shows green fluorescence, and the bottom shows the merged and DIC image. (B) Animals were exposed to inoculum containing either FQ-A001 (WT) or KRG005 (ΔvasH) harboring the reporter plasmid pKRG001, which contains both Phcp-gfp and PtetA-mCherry. After 48 h, fluorescence microscopy was used to record the levels of red and green fluorescence in each light organ. Red fluorescence signal was used as a marker for populations of bacteria within the light organ image. The y axis represents the average ratio between the green and red fluorescence signals at each pixel that was positive for red fluorescence. Each dot represents a different animal in the group and the line represents the median of each group. Differences between groups were determined by Mann-Whitney statistical analysis; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

To establish symbiosis with E. scolopes, V. fischeri must first associate with the light organ and then colonize a crypt space. At each colonized site, direct contact between cells occurs, and certain strains of V. fischeri express a T6SS that affects the outcomes of those direct interactions. Identifying the mechanisms by which the structural components of T6SS are transcriptionally regulated is critical to understanding how T6SS-positive strains of V. fischeri express this weapon during the initial establishment of the light organ symbiosis. In this study, we found that the alternative sigma factor σ54 and the bacterial enhancer binding protein (bEBP) VasH promote transcriptional expression of Hcp, which is a structural component that is necessary for T6SS function (8). Both σ54 and VasH positively regulate transcription of hcp and hcp1 (Fig. 2 and 4), which result in interstrain killing in vitro (Fig. 2 and 5). We also showed that VasH is necessary for the strain incompatibility observed between ES114 and FQ-A001 (Fig. 8). Finally, we found that VasH promotes transcription of hcp within the light organ (Fig. 11).

Taken together, these results suggest a model for Hcp expression, in which σ54 interacts with RNA polymerase at the promoter regions of both hcp and hcp1. As a bEBP, VasH is proposed to bind as a hexamer to a site located upstream of each promoter. The AAA+ domain of VasH catalyzes open complex formation at each promoter, thereby facilitating transcription of hcp and hcp1. The resulting expression of Hcp consequently promotes T6SS assembly and activity. Thus, within the squid host, if a T6SS-positive cell accesses the same crypt space as a T6SS-susceptible cell, injection of effectors by the T6SS will lead to the elimination of the population of T6SS-susceptible cells. This outcome results in the crypt space containing only the T6SS-positive strain, thereby restricting the extent of symbiont diversity an individual squid can harbor.

In FQ-A001, σ54 is necessary for symbiosis establishment (Fig. 6), which is consistent with the previous reports focused on σ54 in ES114 (25). Because σ54 regulates numerous cellular traits that are important for the symbiosis, this alternative sigma factor represents a major regulatory component for V. fischeri to establish symbiosis. There are multiple bEBPs that promote σ54-dependent transcription for various loci in V. fischeri. For instance, SypG specifically activates a cluster of genes involved in oligosaccharide synthesis. This cluster of symbiotic polysaccharide (syp) genes is expressed soon after V. fischeri cells have been recruited from the seawater environment, promoting initial associations with the host (22, 31). LuxO is another bEBP that promotes the expression of a quorum-sensing regulated small RNA, Qrr1, which controls bioluminescence production (32). Finally, FlrA is the bEBP that initiates the regulatory cascade that results in the assembly of the flagellum (25, 33), which enables V. fischeri to swim from the exterior of the light organ into ducts that ultimately lead to interior crypt spaces (18). Here, we show, that the FQ-A001 ΔrpoN mutant, as well as the ES114 ΔrpoN, mutant is nonmotile (Fig. 2), providing empirical evidence that the flagellum-mediated motility necessary for light organ colonization is compromised in these strains. Furthermore, this observation strengthens the case that σ54 has a major role in regulating genes during symbiosis establishment, and may permit easy assimilation of the T6SS genes from horizontal gene transfer into the genes normally expressed during symbiosis. The observation that VasH does not impact the ability for V. fischeri to establish symbiosis may suggest that VasH plays a more specific role in the regulation of microbe-microbe interactions as opposed to host-microbe interactions. Future work will delineate the regulon of VasH and the impact that these gene targets have on interstrain interactions.

It is now thought that T6SS genes are generally regulated by multiple transcription factors, which are often part of diverse signaling pathways that promote secretion in different environments, where contact-dependent killing is advantageous to the bacterial cell (34). In some cases, T6SS is regulated by transcription factors in response to specific stimuli, such as iron starvation via the transcriptional regulator Fur (35). In other cases, global regulators, such as the histone-like nucleoid structuring protein H-NS, have been shown to impact regulation of T6SS core components (36). Quorum sensing is another significant regulatory mechanism for the T6SS (37). For example, the transcription factor HapR induces expression of T6SS genes under conditions of high autoinducer concentrations (38). Other transcription factors that induce T6SS gene expression include the MarR-like transcription factor RovA in Yersinia pestis (39) and the AraC-like transcription factor AggR in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (40). T6SS structural components are often encoded within gene clusters, leading to coregulation among the components that are transcribed as polycistronic messages (37). Previously, induction of hcp expression in an Hcp− strain displayed 48% of WT killing activity (14); however, induction of vasH in the ΔvasH mutant was sufficient to achieve WT killing activity (Fig. 8). This suggests that induction was unable to promote Hcp expression to WT levels. It is also possible that VasH is able to promote the expression of other components besides Hcp that are vital to T6SS function. For example, the hcp1 gene is predicted to be cotranscribed with vgrG (37), which encodes the necessary structural protein that makes up the spiked tip of the T6SS apparatus (8). This suggests that VasH-dependent expression of hcp may also promote expression of other necessary components.

The putative GAF domain of VasH defines this σ54-dependent transcription factor as a group III bEBP (41). In other group III bEBPs, the GAF domain typically binds a small molecule to alleviate steric inhibition of the AAA+ domain. However, in V. cholerae, the GAF domain of the VasH homolog has been shown to be unnecessary for Hcp expression and does not demonstrate any inhibitory function (15). Consistent with this model, induction of vasH expression in the ΔvasH mutant of FQ-A001 complements T6SS-dependent phenotypes (Fig. 8). If the GAF domain in V. fischeri does not play a major role in VasH activity, transcriptional regulation of vasH would provide the opportunity for cells to tightly regulate VasH-dependent targets, such as Hcp. Because our results presented here suggest VasH-dependent regulation of Hcp presents a mechanism to control T6SS within the host, future studies will investigate the mechanisms regulating VasH expression in V. fischeri.

Using genetic approaches to interrogate regulation of the T6SS in V. fischeri, we have found that the T6SS is positively regulated by σ54 and the bEBP VasH during symbiosis. The role and prevalence of the T6SS in beneficial bacteria is an emerging field of study that is revealing the impact of the T6SS weapon on microbiota composition and assembly (12, 42, 43). A current obstacle to understanding how the T6SS affects the assembly of symbiont populations within a host ecosystem has been the inability to study the factors that regulate these nanomachines during symbiosis establishment. These findings provide the foundation for future investigation into the mechanisms used by symbionts to regulate T6SS expression over the course of symbiosis establishment, from initial colonization of the host to prolonged association and expression of symbiotic traits within the host ecosystem.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and growth conditions.

V. fischeri strains were grown aerobically in LBS medium (1% [wt/vol] tryptone, 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 2% [wt/vol] NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]) (44). When appropriate, LBS was supplemented with chloramphenicol at a final concentration of 2.5 μg ml−1 and/or erythromycin (Erm) at a final concentration of 5 μg ml−1.

Strains and plasmids.

The V. fischeri strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| ES114 | Wild-type V. fischeri | 47 |

| FQ-A001 | T6SS+ wild-type V. fischeri | 21 |

| KRG005 | FQ-A001 ΔvasH | This study |

| KRG007 | FQ-A001 ΔrpoN | This study |

| NPW58 | FQ-A001 Δhcp Δhcp1 | 14 |

| TIM313 | ES114 Tn7::erm | 46 |

| KRG003 | ES114 ΔrpoN | This study |

| EVS102 | ES114 ΔluxCDABEG | 48 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSCV38 | pVSV105 PtetA-yfp PtetA-mCherry | 49 |

| pYS112 | pVSV105 PtetA-cfp PtetA-mCherry | 21 |

| pKRG001 | Phcp-gfp | This study |

| pKRG024 | Ptrc-vasH | This study |

| pNPW015 | Phcp1-gfp | This study |

| pVSV105 | R6Kori ori(pES213) RP4 oriT cat | 50 |

| pKV494 | ErmR flanked by FRT sites | 45 |

| pKV496 | FLPase | 45 |

| pTM214 | pVSV105 Ptrc-mCherry | 51 |

| pTM267 | pVSV105 PtetA-mCherry kan::gfp | 46 |

Construction of deletion alleles. The deletion alleles for ΔrpoN and ΔvasH were generated using a recombineering technique as described in reference 45. WT FQ-A001 cells were naturally transformed with linear DNA containing an Ermr cassette flanked by 500 bp upstream and downstream of the gene of interest. Loss of the gene of interest was determined by selection on solid medium containing Erm and confirmed using colony PCR. The Ermr cassette was then removed using a plasmid containing FLP recombinase (pKV496) (45) and recognition of FLPase recognition target sites upstream and downstream of the Ermr cassette. Loss of the gene of interest was confirmed by Sanger sequencing of the region targeted for mutagenesis. Primers for generating deletions are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers

| Primer name | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| FQ_rpoN Del Up F | CCTCAAGAAGCTTCTATTTTTAGA |

| FQ_rpoN Del Up R | TAGGCGGCCGCACTAAGTATGGTATTTAGCGATACCTTTTGTACAT |

| FQ_rpoN Del Down F | GGATAGGCCTAGAAGGCCATGGTTAATTAAAAGGAAGTGTTATGCA |

| FQ_rpoN Del Down R | GATAGCTATCCCATTACCTATACC |

| FQ rpoN check ext F | CGCTCAAAAATGGGGATAGGCTATC |

| FQ rpoN check int F | CAATTTAAGTTGTAATGTACAAAAG |

| FQ rpoN check ext R | GCTTACATTGTTCATCAGGAACGAG |

| FQ_vasH Check int u2 | ATTTCTTAATAAAAAACCGCCTTCG |

| FQ_vasH Check int l2 | TACTCAAATCGTGATTTCAATTGATG |

| FQ_vasH Check ext l2 | GGATGAAGTTGAAAAAGCAGATCCA |

| EYFP SalI u1 | CGCGAGCTCATGCCAACTCCAGCATATATGTCAA |

| EYFP XmnI l1 | ATGGTACCTTATGCTTCGCGTGGTGTACGCCAGTC |

| cL1 | CCATACTTAGTGCGGCCGCCTA |

| cL2 | CCATGGCCTTCTAGGCCTATCC |

| FQ_vasH Del Up F | GTATTCGATAAAGGCACATTAAATG |

| FQ_vasH Del Up R | TAGGCGGCCGCACTAAGTATGGTTAGCTAAAGACATAACCTAGTGT |

| FQ_vasH Del Down F | GGATAGGCCTAGAAGGCCATGGATGAAACCATACTTACTATTATTAC |

| FQ_vasH Del Down R | ATAGAAAAAGAGTGAATTACATGAA |

| FQAvasH_iptg-SacI-u1 | ATTGAGCTCTTAAAGTATCTGTTCAGATGAAATATTATG |

| FQAvasH_iptg-KpnI-l1 | GTGGTACCCTCAAATCGTGATTTCAATTGATGA |

| FQ_Phcp1-gfp–u1 | ATTCCCGGGCTTGGAGCCTTATAATTTTAGAACA |

| FQ_Phcp1-gfp–l1 | CGTCTAGAGGCTTTATTCCTTAATATTAAATTCTATTG |

| FQ_Phcp-gfp_XmaI-u1 | ATTCCCGGGATTTATCATAGTTAGTTTCAATCA |

| FQ_Phcp-gfp_XbaI-l1 | CGTCTAGAGCTATTATCCTTTCATTAATAATTATT |

| ES_rpoN Del Up F | CCTCAAGAAGCTTCTATTTTTAGAA |

| ES_rpoN Del Up R | TAGGCGGCCGCACTAAGTATGGTATTTAGCGATACCTTTTGTACATT |

| ES_rpoN Del Down F | GGATAGGCCTAGAAGGCCATGGTTAATGAAAAGGAAGTGTTATGCAA |

| ES_rpoN Del Down R | GATAGCTATCCCATTACCTATACCA |

| ES_rpoN_Check inner F | GTTGTAATGTACAAAAGGTATCGCT |

| ES_rpoN_Check inner R | TTGCATAACACTTCCTTTTCATTAA |

| ES_rpoN_Check outer F | TTCGATTACTATTGATGGTGTCGAC |

| ES_rpoN_Check outer R | GGACGATTATCAATAGCATCAAATT |

Construction of plasmids. Promoter reporter plasmids were constructed by amplifying promoter regions from FQ-A001 genomic DNA by PCR. The resulting amplicons were introduced to the pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen) and verified by Sanger sequencing. These promoter regions were then excised from pCR-Blunt by restriction digest using XbaI and XmaI restriction enzymes (New England BioLabs) and subcloned into the pTM267 vector (46). The inducible vasH expression vector was constructed via PCR amplification of vasH from FQ-A001 genomic DNA using the primers listed in Table 1. The vasH amplicon was then cloned into pTM214, downstream of the Ptrc promoter using restriction enzymes KpnI and SacI (New England BioLabs).

Squid colonization assays.

LBS cultures grown overnight at 28°C with shaking were first normalized to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0 and then diluted 1:100 into LBS medium. For strains harboring plasmids for labeling with fluorescence, the medium contained 2.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol. At OD600 = 1.0, cultures were diluted into filter-sterilized seawater (FSSW) and combined as indicated to generate each inoculum. Freshly hatched juvenile squid were exposed to the inoculum for 3.5 h, after which animals were washed of the inoculum by being transferred to 100 ml fresh FSSW twice. At 24 postinoculation (p.i.), animals were transferred to fresh FSSW. At 48 h p.i., animals were cooled on ice and then fixed and imaged by fluorescence microscopy as previously described (11). Animal luminescence was measured using a GloMax 20/20 luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI).

For in vivo gene expression assays, fluorescence from bacterial populations within the juvenile squid light organ was quantified by imaging using microscopy as previously described (44). Populations were identified by detecting the presence of an mCherry signal. The background mCherry and GFP signals associated with host tissue were background subtracted using custom Matlab scripts (44). Then, the background-subtracted GFP/mCherry ratios were calculated for each pixel within the defined bacterial population. Ultimately, the average ratio for the entire animal was reported.

Pennsylvania State University does not require Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approval to conduct the studies reported here with the invertebrate animal E. scolopes.

Coincubation assays.

LBS cultures grown overnight at 28°C with shaking were first normalized in LBS to an OD600 of 1.0. The assay was initiated using by combining 50-μl cell suspensions of each strain into a microcentrifuge tube, and then a 10-μl volume was spotted onto the surface of LBS medium containing 1.5% agar, which was incubated at 24°C. The spots were either harvested for CFU counts or visualized by fluorescence microscopy (11).

To determine cellular abundance within a spot, flame-sterilized forceps were used to extract the spot and corresponding agar fragment. Cells were released from the agar into 1 ml LBS by vortexing for 10 s, after which serial dilutions were performed and plated onto LBS agar with or without antibiotic for CFU counts (14).

For fluorescence measurements, spots were incubated for 24 h and then examined at ×2.5 magnification using an SZX16 dissecting microscope (Olympus, Waltham, MA) equipped with an SDF PLFL 0.3× objective and filter sets for CFP and YFP fluorescence. Images of blue (CFP) and yellow (YFP) fluorescence signals of each spot were obtained using an EOS Rebel T5 camera (Canon, Melville, NY) attached to the camera port of the microscope and set for RAW image format. Images were converted to RGB TIFF format using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and the look-up table (LUT) of the images was scaled uniformly across samples as previously described (14).

Motility assays.

LBS cultures grown overnight at 28°C with shaking were used to inoculate soft-agar plates containing 0.25% tryptone, 0.15% yeast extract, 70% Instant Ocean seawater (synthetic salt mix in deionized [DI] water diluted to 35 ppt), and 0.125% agar. A 5-μl volume of the overnight culture was injected into the center of the soft-agar plate and motility at 28°C was tracked by measuring the diameter of the motility ring every 2 h. Motility rates for each bacterial strain were determined by performing a linear regression analysis on the measurements over time.

Bioluminescence assays.

LBS cultures grown overnight at 28°C with shaking were normalized to an OD600 of 1 and diluted 1:100 into fresh LBS medium. After 2 h, the culture was again diluted 1:10 into LBS media in the presence or absence of 120 nM N-3-oxohexanoyl-l-homoserine lactone and subsequently incubated aerobically at 28°C until the culture reached an OD600 of ∼1.0. Bioluminescence was measured using a GloMax 20/20 luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01-GM129133 (to T.M.).

The funders had no role in study, design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dimijian GG. 2000. Evolving together: the biology of symbiosis, part 1. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 13:217–226. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2000.11927677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouchon D, Zimmer M, Dittmer J. 2016. The terrestrial isopod microbiome: an all-in-one toolbox for animal-microbe interactions of ecological relevance. Front Microbiol 7:1472. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florez LV, Biedermann PH, Engl T, Kaltenpoth M. 2015. Defensive symbioses of animals with prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms. Nat Prod Rep 32:904–936. doi: 10.1039/c5np00010f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swain Ewald HA, Ewald PW. 2018. Natural selection, the microbiome, and public health. Yale J Biol Med 91:445–455. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh P-F, Lu Y-R, Lin T-L, Lai L-Y, Wang J-T. 2019. Klebsiella pneumoniae type VI secretion system contributes to bacterial competition, cell invasion, type-1 fimbriae expression, and in vivo colonization. Infec Dis 219:637–647. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sana TG, Flaugnatti N, Lugo KA, Lam LH, Jacobson A, Baylot V, Durand E, Journet L, Cascales E, Monack DM. 2016. Salmonella Typhimurium utilizes a T6SS-mediated antibacterial weapon to establish in the host gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E5044–E5051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608858113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshi A, Kostiuk B, Rogers A, Teschler J, Pukatzki S, Yildiz FH. 2017. Rules of engagement: the type VI secretion system in Vibrio cholerae. Trends Microbiol 25:267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho BT, Dong TG, Mekalanos JJ. 2014. A view to a kill: the bacterial type VI secretion system. Cell Host Microbe 15:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Revel AT, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ. 2007. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:15508–15513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706532104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Sturtevant D, Krastins B, Sarracino D, Nelson WC, Heidelberg JF, Mekalanos JJ. 2006. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speare L, Cecere AG, Guckes KR, Smith S, Wollenberg MS, Mandel MJ, Miyashiro T, Septer AN. 2018. Bacterial symbionts use a type VI secretion system to eliminate competitors in their natural host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E8528–E8537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1808302115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verster AJ, Ross BD, Radey MC, Bao Y, Goodman AL, Mougous JD, Borenstein E. 2017. The landscape of type VI secretion across human gut microbiomes reveals its role in community composition. Cell Host Microbe 22:411–419.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coyne MJ, Comstock LE. 2019. Type VI Secretion Systems and the Gut Microbiota. Microbiol Spectr 7. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.PSIB-0009-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guckes KR, Cecere AG, Wasilko NP, Williams AL, Bultman KM, Mandel MJ, Miyashiro T. 2019. Incompatibility of Vibrio fischeri strains during symbiosis establishment depends on two functionally redundant hcp genes. J Bacteriol 201:e00221-19. doi: 10.1128/JB.00221-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitaoka M, Miyata ST, Brooks TM, Unterweger D, Pukatzki S. 2011. VasH is a transcriptional regulator of the type VI secretion system functional in endemic and pandemic Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 193:6471–6482. doi: 10.1128/JB.05414-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mougous JD, Cuff ME, Raunser S, Shen A, Zhou M, Gifford CA, Goodman AL, Joachimiak G, Ordonez CL, Lory S, Walz T, Joachimiak A, Mekalanos JJ. 2006. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science 312:1526–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.1128393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lien YW, Lai EM. 2017. Type VI secretion effectors: methodologies and biology. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:254. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFall-Ngai M. 2014. Divining the essence of symbiosis: insights from the squid-vibrio model. PLoS Biol 12:e1001783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones BW, Nishiguchi MK. 2004. Counterillumination in the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes Berry (Mollusca: Cephalopoda). Marine Biology 144:1151–1155. doi: 10.1007/s00227-003-1285-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFall-Ngai MJ, Ruby EG. 1991. Symbiont recognition and subsequent morphogenesis as early events in an animal-bacterial mutualism. Science 254:1491–1494. doi: 10.1126/science.1962208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Y, LaSota ED, Cecere AG, LaPenna KB, Larios-Valencia J, Wollenberg MS, Miyashiro T. 2016. Intraspecific competition impacts Vibrio fischeri strain diversity during initial colonization of the squid light organ. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:3082–3091. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04143-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yip ES, Grublesky BT, Hussa EA, Visick KL. 2005. A novel, conserved cluster of genes promotes symbiotic colonization and sigma-dependent biofilm formation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 57:1485–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morett E, Buck M. 1989. In vivo studies on the interaction of RNA polymerase-sigma 54 with the Klebsiella pneumoniae and Rhizobium meliloti nifH promoters. The role of NifA in the formation of an open promoter complex. J Mol Biol 210:65–77. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danson AE, Jovanovic M, Buck M, Zhang X. 2019. Mechanisms of sigma(54)-dependent transcription initiation and regulation. J Mol Biol 431:3960–3974. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfe AJ, Millikan DS, Campbell JM, Visick KL. 2004. Vibrio fischeri σ54 controls motility, biofilm formation, luminescence, and colonization. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:2520–2524. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2520-2524.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wollenberg MS, Ruby EG. 2009. Population structure of Vibrio fischeri within the light organs of Euprymna scolopes squid from two Oahu (Hawaii) populations. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:193–202. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01792-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Letunic I, Bork P. 2018. 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res 46:D493–D496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bultman KM, Cecere AG, Miyashiro T, Septer AN, Mandel MJ. 2019. Draft genome sequences of type VI secretion system-encoding Vibrio fischeri strains FQ-A001 and ES401. Microbiol Resour Announc 8:e00385-19. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00385-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruby EG, Urbanowski M, Campbell J, Dunn A, Faini M, Gunsalus R, Lostroh P, Lupp C, McCann J, Millikan D, Schaefer A, Stabb E, Stevens A, Visick K, Whistler C, Greenberg EP. 2005. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:3004–3009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409900102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y, Verma SC, Bogale H, Miyashiro T. 2015. NagC represses N-acetyl-glucosamine utilization genes in Vibrio fischeri within the light organ of Euprymna scolopes. Front Microbiol 6:741. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray VA, Eddy JL, Hussa EA, Misale M, Visick KL. 2013. The syp enhancer sequence plays a key role in transcriptional activation by the sigma54-dependent response regulator SypG and in biofilm formation and host colonization by Vibrio fischeri. J Bacteriol 195:5402–5412. doi: 10.1128/JB.00689-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lupp C, Urbanowski M, Greenberg EP, Ruby EG. 2003. The Vibrio fischeri quorum-sensing systems ain and lux sequentially induce luminescence gene expression and are important for persistence in the squid host. Mol Microbiol 50:319–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.t01-1-03585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Syed KA, Beyhan S, Correa N, Queen J, Liu J, Peng F, Satchell KJF, Yildiz F, Klose KE. 2009. The Vibrio cholerae flagellar regulatory hierarchy controls expression of virulence factors. J Bacteriology 191:6555–6570. doi: 10.1128/JB.00949-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverman JM, Brunet YR, Cascales E, Mougous JD. 2012. Structure and regulation of the type VI secretion system. Annu Rev Microbiol 66:453–472. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-121809-151619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Wang Q, Xiao J, Liu Q, Wu H, Xu L, Zhang Y. 2009. Edwardsiella tarda T6SS component evpP is regulated by esrB and iron, and plays essential roles in the invasion of fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol 27:469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang FC, Rimsky S. 2008. New insights into transcriptional regulation by H-NS. Curr Opin Microbiol 11:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernard CS, Brunet YR, Gueguen E, Cascales E. 2010. Nooks and crannies in type VI secretion regulation. J Bacteriol 192:3850–3860. doi: 10.1128/JB.00370-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishikawa T, Rompikuntal PK, Lindmark B, Milton DL, Wai SN. 2009. Quorum sensing regulation of the two hcp alleles in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains. PLoS One 4:e6734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cathelyn JS, Crosby SD, Lathem WW, Goldman WE, Miller VL. 2006. RovA, a global regulator of Yersinia pestis, specifically required for bubonic plague. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:13514–13519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603456103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dudley EG, Thomson NR, Parkhill J, Morin NP, Nataro JP. 2006. Proteomic and microarray characterization of the AggR regulon identifies a pheU pathogenicity island in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 61:1267–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bush M, Dixon R. 2012. The role of bacterial enhancer binding proteins as specialized activators of sigma54-dependent transcription. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:497–529. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00006-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Logan SL, Thomas J, Yan J, Baker RP, Shields DS, Xavier JB, Hammer BK, Parthasarathy R. 2018. The Vibrio cholerae type VI secretion system can modulate host intestinal mechanics to displace gut bacterial symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:e3779–e3787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720133115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen C, Yang X, Shen X. 2019. Confirmed and potential roles of bacterial T6SSs in the intestinal ecosystem. Front Microbiol 10:1484. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wasilko NP, Larios-Valencia J, Steingard CH, Nunez BM, Verma SC, Miyashiro T. 2019. Sulfur availability for Vibrio fischeri growth during symbiosis establishment depends on biogeography within the squid light organ. Mol Microbiol 111:621–636. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Visick KL, Hodge-Hanson KM, Tischler AH, Bennett AK, Mastrodomenico V. 2018. Tools for rapid genetic engineering of Vibrio fischeri. Appl Environ Microbiol 84: e00850-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00850-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyashiro T, Wollenberg MS, Cao X, Oehlert D, Ruby EG. 2010. A single qrr gene is necessary and sufficient for LuxO-mediated regulation in Vibrio fischeri. Mol Microbiol 77:1556–1567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boettcher KJ, Ruby EG. 1990. Depressed light emission by symbiotic Vibrio fischeri of the sepiolid squid Euprymna scolopes. J Bacteriol 172:3701–3706. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3701-3706.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bose JL, Rosenberg CS, Stabb EV. 2008. Effects of luxCDABEG induction in Vibrio fischeri: enhancement of symbiotic colonization and conditional attenuation of growth in culture. Arch Microbiol 190:169–183. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0387-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verma SC, Miyashiro T. 2016. Niche-specific impact of a symbiotic function on the persistence of microbial symbionts within a natural host. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:5990–5996. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01770-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dunne C, Dolan B, Clyne M. 2014. Factors that mediate colonization of the human stomach by Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol 20:5610–5624. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyashiro T, Klein W, Oehlert D, Cao X, Schwartzman J, Ruby EG. 2011. The N-acetyl-D-glucosamine repressor NagC of Vibrio fischeri facilitates colonization of Euprymna scolopes. Mol Microbiol 82:894–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]