Dear Sir,

We read the Editorial “CORONA-steps for tracheotomy in COVID-19 patients: A staff-safe method for airway management”, by Pichi et al. [1].

We congratulate the authors on their work, however, basing on our experience in COVID-19 pneumonia patients in one of Italy’s national “hot spots” (“San Salvatore” Civil Hospital of Pesaro, Marche Region), we believe some more tips to minimize the risk of health care workers’ (HCWs) infection may be reported.

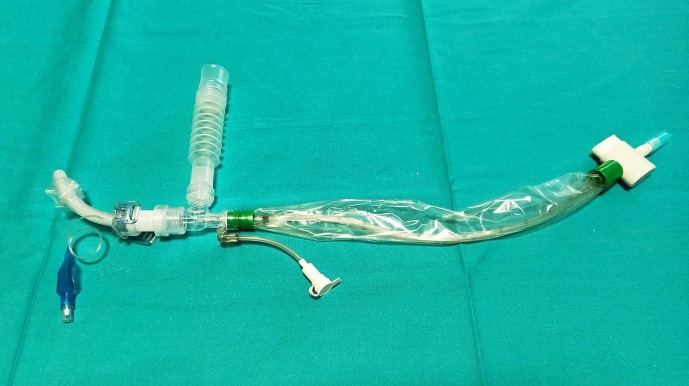

We agree with the authors on the importance of personal protective equipment (PPE) and operating room (OR) setting. As to “open the trachea” item, basing on our experience on 22 Caucasian patients (19M, 3F), mean age 67 years (age range: 47–74), submitted to surgical tracheostomy between February 3rd and March 14th 2020, after a long (mean: 21.54 ± 2.11 days) orotracheal intubation for sever acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pneumonia, we suggest the following tips: (1) Pichi et al. “push the tube as caudally as possible” before opening the trachea (intraoperatively) [1]. Such manoeuvrer requires a cuff deflation-reinflation step, during which patient’s bronchi/lungs are not totally “excluded” from his/her upper airways, with a consequent potential intraoperative risk for infected expired air/aerosol drops to infect HCWs (intensive care specialist and anaesthetist assistant nurse in particular). We prefer to push the endotracheal tube forward along the tracheal lumen until its cuff is placed just above the carina before surgery to erase this contamination risk. (2) The authors reduce “the oxygeneation-percentage of the inflated air to 21%” before trachea opening and “entirely stop ventilation” on endotracheal tube removal [1]. On the contrary, once the anterior tracheal wall is exposed, we carry out an adequate preoxygenation (100% oxygen for 3 min) and then stop mechanical ventilation 30 s before the tracheal anterior wall is opened (pre-tracheotomy apnoea). This procedure, as already described by Wei et al. [2], prevents the expired infected air to come out under pressure (“champagne effect”) from the patient’s lower airways through the tracheostomy site after deflation of the endotracheal tube cuff with a consequent reduction of HCWs’ risk of contamination. (3) In order to minimize HCWs’ intraoperative time exposure to patients’ aerosolized secretions, we connect the tracheostomy cannula with a Halyard closed suction system® (which is attached to the ventilator at the end of the procedure) before trachea opening and cannula insertion into the trachea (Fig. 1 ). The time interval between deflation of the endotracheal tube cuff and connection of the cuffed tracheostomy cannula-Halyard closed suction system® to the ventilator (“air exposure time”, AET) is one of the most risky phases [2] for HCWs’ contamination since the patient’s lower airways are not totally “excluded” (not connected to the ventilator system) from the external environment. We quantified this contamination risk by measuring AET during our procedures: AET for surgical tracheostomy was 5.5 ± 1.4 s (range: 4–9 s), significantly (p < 0.001) inferior to AET for percutaneous tracheotomy (21.8 ± 5.7 s). This seems to confirm the superior risk of HCWs’ contamination during percutaneous tracheotomy with respect to surgical procedure [3], [4], [5]. Furthermore, the use of Halyard system®, connected to the cannula before tracheal opening, not only minimizes AET, but allows immediate aspiration of tracheal/bronchial infected secretions after endotracheal tube removal through a “closed circuit”. Since “open air” tracheal suctioning by a common aspiration system is considered one of the most dangerous steps for HCWs’ contamination because of aerosol generation [2], Halyard closed system® contributes to minimize the risk of HCWs’ infection. As a confirmation, in our case series, no HCW infection has been recorded so far.

Fig. 1.

Halyard closed suction system® (Registered Trademark or Trademark of Halyard Health, Inc. or its affiliates. Copyright 2016 HYH) connected with the tracheostomy cannula.

In conclusion, we would like to thank Pichi et al. for standardizing the “CORONA-steps for tracheotomy in COVID-19 patients”. We believe combining their steps with the tips we have developed thanks to our COVID-19 experience may be useful for the readers and physicians for a better surgical planning and prevention of HCWs’ infection when performing surgical tracheostomy in patients affected by COVID-19 pneumonia.

Financial support

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors do not have any actual or potential conflict of interest

References

- 1.Pichi B., Mazzola F., Bonsembiante A. CORONA-steps for tracheotomy in COVID-19 patients: A staff-safe method for airway management. Oral Oncol. 2020;105 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei W.I., Tuen H.H., Ng R.W., Lam L.K. Safe tracheostomy for patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(10):1777–1779. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200310000-00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd J.K., Ranasinghe V.J., Day K.E., Wolf B.J., Lentsch E.J. Predictors of clinical outcome after tracheotomy in critically ill obese patients. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(5):1118–1122. doi: 10.1002/lary.24347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Divisi D., Stati G., De Vico A., Crisci R. Is percutaneous tracheostomy the best method in the management of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation? Respir Med Case Rep. 2015;1(16):69–70. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison L, Winter S. Guidance for surgical tracheostomy and tracheostomy tube change during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available: http://www.entuk.org/tracheostomy-guidance-during-covid-19-pandemic.