Abstract

Purpose

Dexmedetomidine is an α2-adrenoceptor agonist used for perioperative and intensive care sedation. This study develops mechanism-based population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic models for the cardiovascular and central nervous system (CNS) effects of intravenously (IV) and intranasally (IN) administered dexmedetomidine in healthy subjects.

Method

Single doses of 84 μg of dexmedetomidine were given once IV and once IN to six healthy men. Plasma dexmedetomidine concentrations were measured for 10 h along with plasma concentrations of norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (E). Blood pressure, heart rate, and CNS drug effects (three visual analog scales and bispectral index) were monitored to assess the pharmacological effects of dexmedetomidine. PK-PD modeling was performed for recently published data (Eur J Clin Pharmacol 67: 825, 2011).

Results

Pharmacokinetic profiles for both IV and IN doses of dexmedetomidine were well fitted using a two-compartment PK model. Intranasal bioavailability was 82 %. Dexmedetomidine inhibited the release of NE and E to induce their decline in blood. This decrease in NE was captured with an indirect response model. The concentrations of the mediator NE served via a biophase/transduction step and nonlinear pharmacologic functions to produce reductions in blood pressure and heart rate, while a direct effect model was used for the CNS effects.

Conclusion

The comprehensive panel of two biomarkers and seven response measures were well captured by the population PK/PD models. The subjects were more sensitive to the CNS (lower EC50 values) than cardiovascular effects of dexmedetomidine.

Keywords: Dexmedetomidine, Mechanism-based modeling, Population pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, α2-adrenoceptor agonist, Norepinephrine

Introduction

Dexmedetomidine, an imidazole compound, is the pharmacologically active D-enantiomer of medetomidine. It is a highly selective and potent α2-adrenoceptor agonist used for perioperative and intensive care sedation with associated reductions in analgesic and anesthetic requirements [1].

The adrenoceptors are a class of G protein-coupled receptors that are targets of the catecholamines norepinephrine (noradrenaline, NE) and epinephrine (adrenaline, E). Adrenoceptors can be subdivided into three groups which comprise α1-receptors (α1A, α1B, α1D), α2-receptors (α2A, α2B, α2C), and β-receptors (β1, β2, β3). The α2-adrenoceptor subtypes are coupled to several signaling pathways which include inhibition of adenylate cyclase and voltage-gated Ca2+ currents and activation of receptor-operated K+ currents [2]. In vivo, α2A- and α2C-receptors control the release of NE from sympathetic nerves and E from the adrenal gland. Activation of α2-adrenoceptor subtypes results in diverse pharmacological and physiological effects, including hypotension, sedation, and analgesia mediated by α2A-adrenoceptors and hypertension mediated by α2B-adrenoceptors [3].

The pharmacological actions of dexmedetomidine in the central nervous system (CNS) results in sedative, hypnotic/anxiolytic, anesthetic, and analgesic effects, with no or minimal respiratory depression [4, 5]. Dexmedetomidine is assumed to exert its sedative and anxiolytic effects mainly through activation of α2A-adrenoceptors in the locus coeruleus [6]. The α2A-subtype is found presynaptically on NE cells and terminals. Activation of presynaptic α2-receptors reduces NE release. Although NE and E produce similar fight-or-flight responses in the body, the psychoactive effects are due to NE release in the CNS while peripheral NE and E do not cross the BBB in sufficient amounts to produce detectable effects. In addition, dexmedetomidine alters blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) due to its sympatholytic properties. A biphasic cardiovascular effect has been reported for dexmedetomidine in healthy subjects [7, 8]. After intravenous (IV) administration, at high plasma concentrations, dexmedetomidine induces a transient increase of BP and a reflex decrease in HR as a result of the activation of peripheral α2-adrenoceptors in vascular smooth muscle, followed by a decrease of BP below baseline due to the central sympathetic inhibition.

Dexmedetomidine is extensively metabolized through glucuronidation and cytochrome P450 metabolism in the liver [9]. The volume of distribution at a steady state of dexmedetomidine is approximately 118 L, and mean elimination half-life is 1.5 to 3 h following IV and intramuscular administration [10]. The average plasma protein binding is 94 % to albumin and α1-glycoprotein [11]. The population PK of dexmedetomidine was evaluated with regard to covariate effects in infants [12] and in intensive care unit patients [13]. The relationship between dexmedetomidine concentrations and the mean arterial BP in children [14] was assessed. The cardiovascular, EEG, hypnotic, and ventilatory effects of dexmedetomidine were examined in rats [15], as well as dexmedetomidine concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid and hemodynamic effects in sheep [16]. While many studies have characterized the PK/PD for some responses of dexmedetomidine, none offered mechanistic approaches to account for the actions of dexmedetomidine as an α2-adrenoceptor agonist with its alteration of catecholamines, key modulators of many hemodynamic and CNS actions.

We executed population PK analysis using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling (NONMEM) to simultaneously fit plasma data following separate IV and intranasal (IN) doses of dexmedetomidine in healthy subjects. The PD effects associated with α2-adrenoceptor agonism including plasma NE and E, BP, HR, subjective effects, and bispectral index were examined to develop mechanism-based PK/PD models to quantitatively describe clinically measurable effects of dexmedetomidine in healthy subjects.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

This study re-analyzed recently published data [17]. The experimental conditions have been described in detail [17]. In brief, 6 healthy Caucasian male volunteers participated. Their ages ranged from 18.5 to 24.8 years (median, 21.5 years), while weights ranged from 60 to 86 kg (83 kg), and body mass index (BMI) ranged from 19.6 to 25.9 kg/m2 (25.3 kg/m2). After receiving approval from the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland and the Finnish Medicines Agency, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. This study (EudraCT 2008-008324-33, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00837187) was conducted according to the revised Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and Good Clinical Practice (ICH GCP) guidelines.

On the study days, the participants fasted from mid-night until 4 h after drug administration. During this period, only water intake was allowed. A venous catheter was inserted into a large forearm vein for administration of dexmedetomidine. An arterial catheter was inserted into the radial artery for blood sampling and BP monitoring. The ECG, BP, and peripheral arteriolar oxygen saturation were monitored continuously. The participants were served standard meals at 4 and 8 h after dexmedetomidine dosing.

Study design

The study was conducted in a two-period, single-dose, randomized, and cross-over design. The dose of 84 μg of dexmedetomidine (0.84 mL of dexmedetomidine hydrochloride 118 μg/mL, corresponding to 100 μg/mL base, Precedex®, Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA) was given IV over 10 min at a constant rate using an infusion pump. Another dose of 84 μg of a more concentrated veterinary formulation (0.2 mL of dexmedetomidine hydrochloride 500 μg/mL, corresponding to 420 μg/mL base, Dexdomitor®, Orion Oyj, Espoo, Finland) was administered intranasally using a nasal spray application system (Spray Pump VP7/100S, 0.1 mL/dose, Valois Pharma, Le Vaudreuil, France). Intranasal dexmedetomidine was dosed in a sitting position, as the nasal spray pump had to be kept in an upright position. The washout period between the two doses was at least 7 days. Arterial blood samples were collected immediately prior to dosing (baseline) and thereafter at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 45 min and 1, 1.5, 2, and 3 h to determine dexmedetomidine, NE, and E in plasma with EDTA as anticoagulant. Additional blood samples were collected at 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10 h to measure dexmedetomidine. The subjects were not allowed to sit or stand up during the first 3 h after dexmedetomidine dosing. After 3 h, the subjects were allowed to sit in their beds. However, during sampling, they were in supine or semi-recumbent positions.

Dexmedetomidine and catecholamine analysis

Concentrations of dexmedetomidine in plasma were measured using a validated HPLC-MS/MS method as previously described [17]. The lower limit of quantitation (LOQ) was 0.02 ng/mL. Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation for all plasma assays were less than 8 %. One BLOQ sample was not included in the fitting. Concentrations of NE and E in plasma were measured using HPLC and coulometric electrochemical detection [18].

Pharmacodynamic measurements

Systolic arterial pressure (SAP) and diastolic arterial pressure (DAP) and HR were measured to assess the sympatholytic effects of dexmedetomidine. The bispectral index was used to monitor the level of sedation [19]. Subjective effects were recorded with 100-mm horizontal visual analog scales (VAS) with opposite qualities at each end (no effects/very strong effects of the drug, excellent/poor performance, alert/drowsy) [20].

Structural models

Pharmacokinetics

The plasma dexmedetomidine concentration versus time data after the single IV and IN doses of dexmedetomidine was modeled simultaneously. One-, two-, and three-compartment disposition models were tested. The drug input was modeled with zero-order input for IV and first-order absorption (ka) with a lag time for IN doses. Linear kinetics was assumed.

The equations and initial conditions (IC) for the two-compartment model are

where A and C are the amount and concentration of dexmedetomidine, CL is elimination clearance, CLD is inter-compartmental clearance, V1 and V2 are volumes of the central and peripheral compartments, and ka and F are the absorption rate constant and the bioavailability of dexmedetomidine after IN administration.

Pharmacodynamics

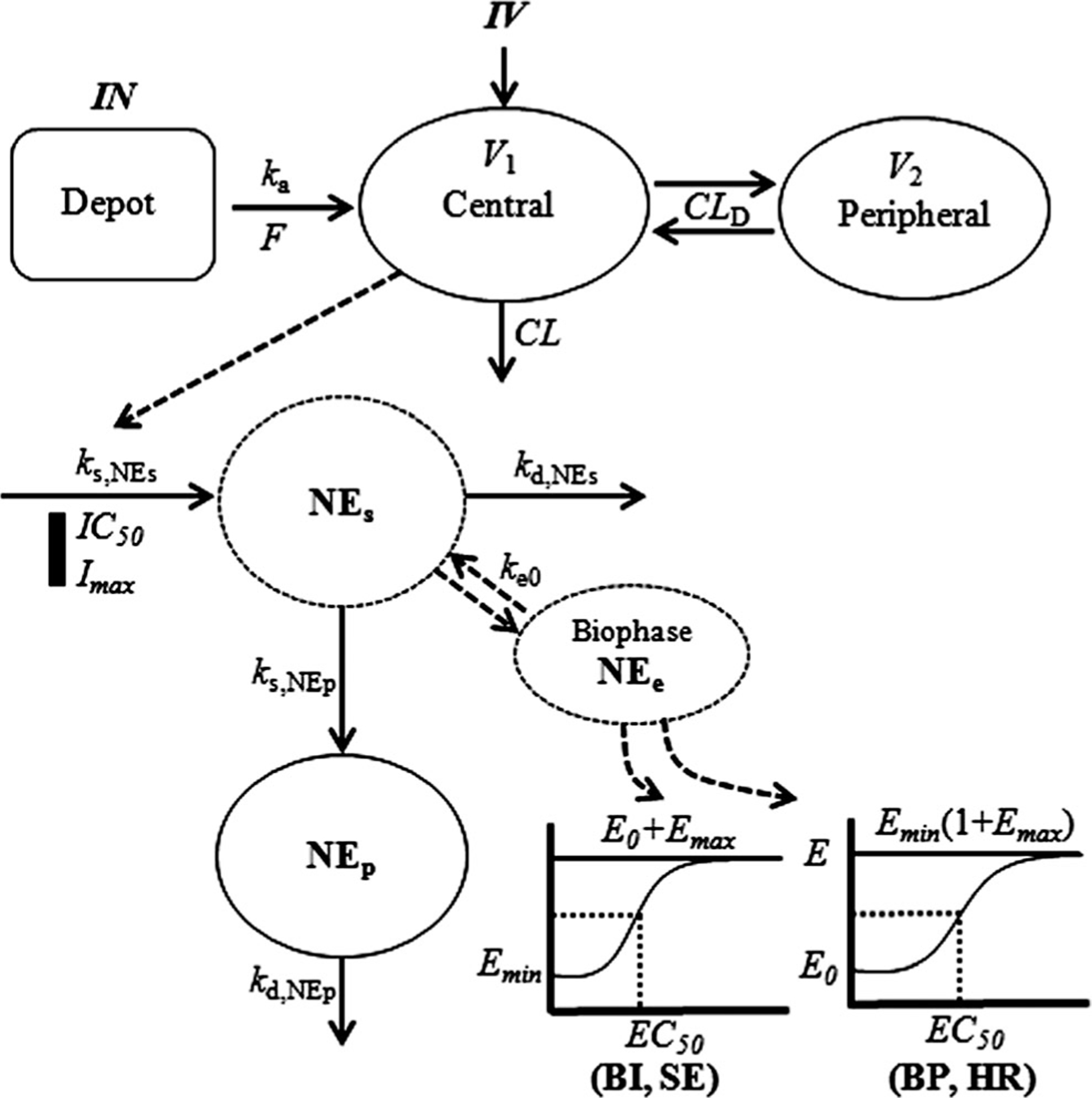

The primary PD model employed is shown in Fig. 1. The decrease in plasma NE (NEp) after dexmedetomidine administration was captured with an indirect response model linked with a biophase to represent the inhibition of NE (NEs) release from sympathetic nerves. The equations and IC are

Fig. 1.

PK/PD model diagram for the effects of dexmedetomidine on inhibition of norepinephrine (NE) release, and biophase model for NE control of blood pressure (SAP and DAP) and heart rate, subjective effects, and bispectral index

The decrease in plasma E after dexmedetomidine administration was also captured with an indirect response model. The equations and IC are

where ks is the production rate constant, kd is the disposition rate constant, Fm is the spillover fraction of NE from sympathetic nerves fixed as 0.15 as previously reported [21, 22], and IC50 is the concentration of dexmedetomidine at which the appearance rate into plasma of NEs and Ep is reduced to 50 % of its baseline.

For the effects of NE on BP (SAP and DAP), biophase/transduction and joint effect models were tested. The equations and IC for the model linked via an effect site and a sigmoidal Emax function are

where NEe is the NE in the biophase, ke0 is the rate constant for the effect compartment, , is the NEe at 50 % of the maximal BP, γ is the Hill coefficient, and is the minimum effect of NEe on BP. According to Wohlfart et al. [23], maximal SAP (SAPmax) can be described by a linear function based on age: SAPmax = 0.505 × age + 192 (for men). We assumed DAPmax as 140 mmHg [24]. Therefore, was set using maximal SAP (or DAP) as .

The effect of NE on HR was assessed using biophase and joint effect models. The model with the biophase and sigmoidal Emax function controlled by the parameters and is:

where was set as . There are several reports regarding maximum possible HR in humans [25–28]. We assumed HRmax as 203.7/(1+exp(0.033 [age–104.3])) [23]. Fitted parameters thus were Emin, EC50, γ, and ke0 for both BP and HR. Emax is a secondary parameter.

For the effects of NE on subjective effects and bispectral index, direct effect and biophase linked with joint effect models were tested. The NEs was assumed to directly alter subjective effects and bispectral index in the direct effect model. Subjective effects were inversely proportional to NE as they increased as plasma concentrations of NE decreased. Thus, the effect of NE on drug effect, performance, and drowsiness was modeled with a sigmoidal Emax function that includes a baseline effect , controlled by the parameters and as:

The effect of NEe on bispectral index was modeled as sigmoidal Emax model that includes a baseline effect , controlled by the parameters and as:

where is the baseline of bispectral index produced by NEe. Fitted parameters were EC50, γ, and sometimes either E0 or Emax.

Data analysis

A sequential population model was developed using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling as implemented in NONMEM (version 7.3.0; ICON Development Solutions, Hanover, MD) to estimate the population mean parameters, inter-individual (η), and residual (ε) random effects [29]. The basic population model was implemented in the PREDPP library subroutine ADVAN6 and TOL=3 in NONMEM and estimated using the first-order conditional estimation (FOCE) method with η–ε interaction. The inter-individual variability of each of the structural parameters of the basic model was modeled using an exponential error model:

where Pi is the value of the parameter in an ith individual6, ηi is a random variable and the difference between Pi and PTV which is the value of the parameter in a typical individual. It is assumed that the values of ηi are normally distributed with a mean of zero and a variance of ω2. The residual variability was evaluated (i.e., additive error, proportional error, and combined additive and proportional error model) to describe the intra-subject variability. The combined additive and proportional error model described the residual variability based on:

where Cij is the jth observed value in the ith subject, Cpred,ij is the jth predicted value in the ith subject, and the proportional (εpro,ij) and additive (εadd,ij) error are the residual intra-subject variability with means of zero and variances of σpro2 and σadd2. Each parameter was sequentially tested to determine if it should remain in the basic model. In addition, the influence of subject covariates on the PK parameters was analyzed. The covariates included in this analysis were limited to age, weight, height, and BMI since all subjects were healthy male volunteers.

The most appropriate pharmacostatistical model was selected on the basis of goodness-of-fit plots, precision of estimates and the likelihood ratio test within NONMEM. In the case of non-nested models, the value of the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) was used. The significance level was P<0.05 during forward inclusion and P<0.01 during backward deletion. The goodness-of-fit plots included plots of the observed and predicted individual profiles, and the population predicted estimates, and conditional weighted residuals [30] which were obtained using Xpose software. The precision of the population estimates was evaluated on the basis of relative standard errors (RSE%). The inter-individual variability was estimated in terms of the coefficient of variance (CV%).

The accuracy and robustness of the final population model were evaluated using visual predictive checks (VPC) implemented in Xpose with the PsN. The predicted estimates-time profiles for 1000 datasets at each time point were generated from the parameters and variances of the selected final model. The 90 % prediction intervals (5th to 95th percentile) of simulated dexmedetomidine concentrations and all PD measures at times corresponding to the observed values were calculated and plotted for comparison with observed values.

Results

Pharmacokinetics

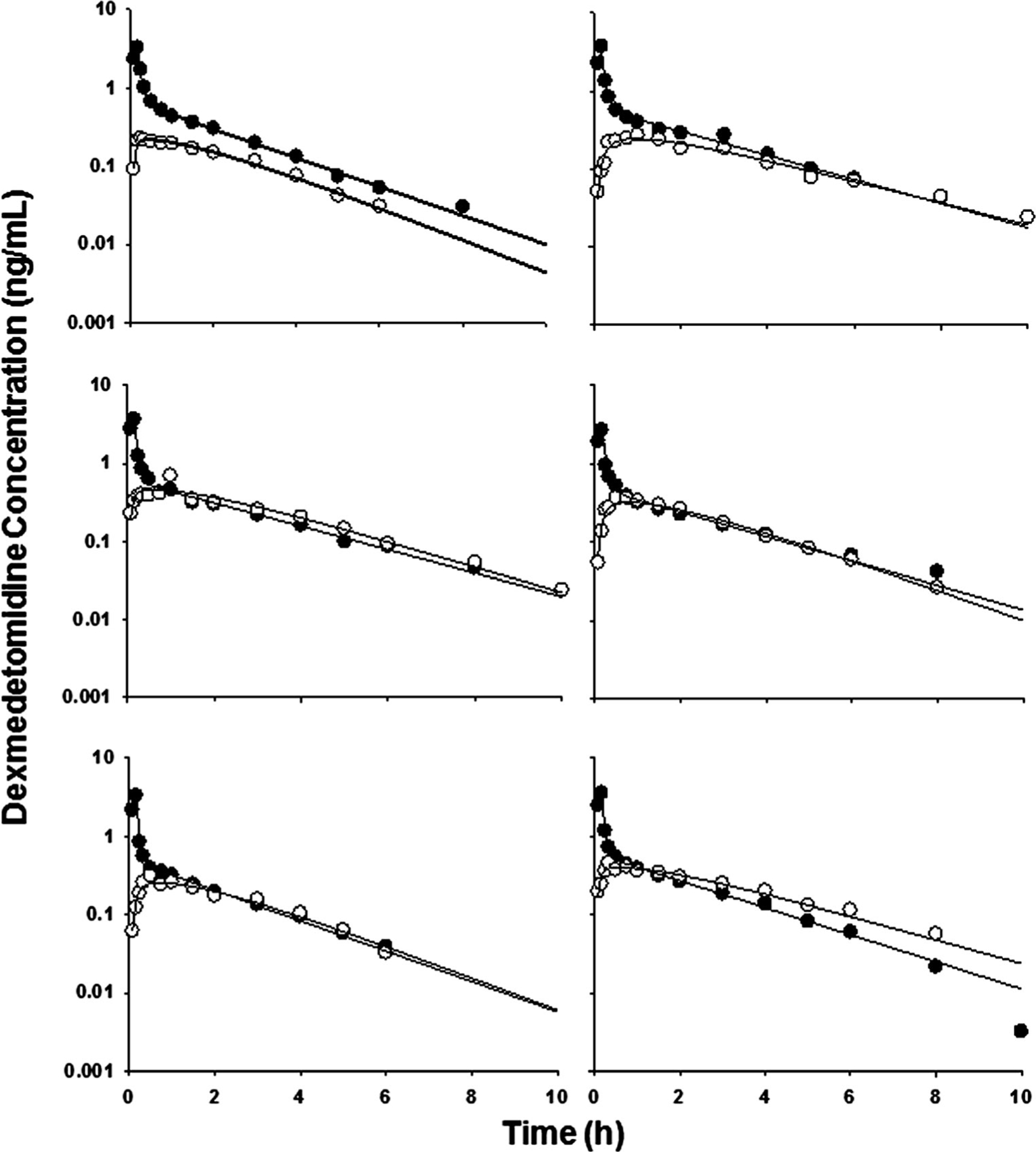

The observed plasma concentration versus time profiles after IV and IN doses is shown in Fig. 2 along with the fitted curves for all subjects. The IV curves were bi-exponential with a terminal half-life of 1.9 h. The IN dose exhibited an absorption phase with a mean Cmax of 0.314 ng/mL at a Tmax of 0.5 h.

Fig. 2.

Dexmedetomidine concentrations in plasma after IV (closed circles) and IN (open circles) administration to six healthy male volunteers. Solid lines represent individual predictions

The plasma concentration profiles were well described by a two-compartment linear model with zero-order input for IV and first-order absorption for IN with a lag time. The clearance was 44 L/h, and the IN absorption rate constant was 0.94 h−1. The fitted parameters indicate that 82 % (F value) of the drug in the nasal site can be absorbed after a slight lag time (about 2.6 min).

The AIC significantly decreased for the two-compartment model when compared with the one- and three-compartment models. Simultaneous fitting of IV and IN data of dexmedetomidine allowed resolution of all kinetic parameters with reasonable precision (Table 1). The OFV decreased further in response to the inclusion of a random effect on V1, CL, and V2 (P<0.001). However, including a random effect on ka and CLD was not significant. Inclusion of a lag time in the model led to a significant decrease in OFV (P<0.001). The best residual error model for dexmedetomidine was a proportional error.

Table 1.

Population pharmacokinetic parameters for dexmedetomidine

| Parameter (unit) | Definition | Estimate | Inter-individual variability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 (L) | Central volume | 14.3 | (20.5) | 0.33 (38.6) [2] |

| CL (L/h) | Systemic clearance | 44.0 | (7.0) | 0.058(41.3) [4] |

| V2 (L) | Peripheral volume | 75.0 | (6.1) | 0.021 (49.5) [8] |

| CLD (L/h) | Inter-compartmental clearance | 103 | (5.1) | - |

| ka (h−1) | Absorption rate constant | 0.94 | (9.6) | - |

| F | Bioavailability | 0.82 | (5.4) | - |

| ALAG (h) | Lag time | 0.0428 | (17.1) | - |

| Residual variability | ||||

| Proportional error | 0.112 | (6.3) | ||

(%) RSE, [%] shrinkage

Pharmacodynamics

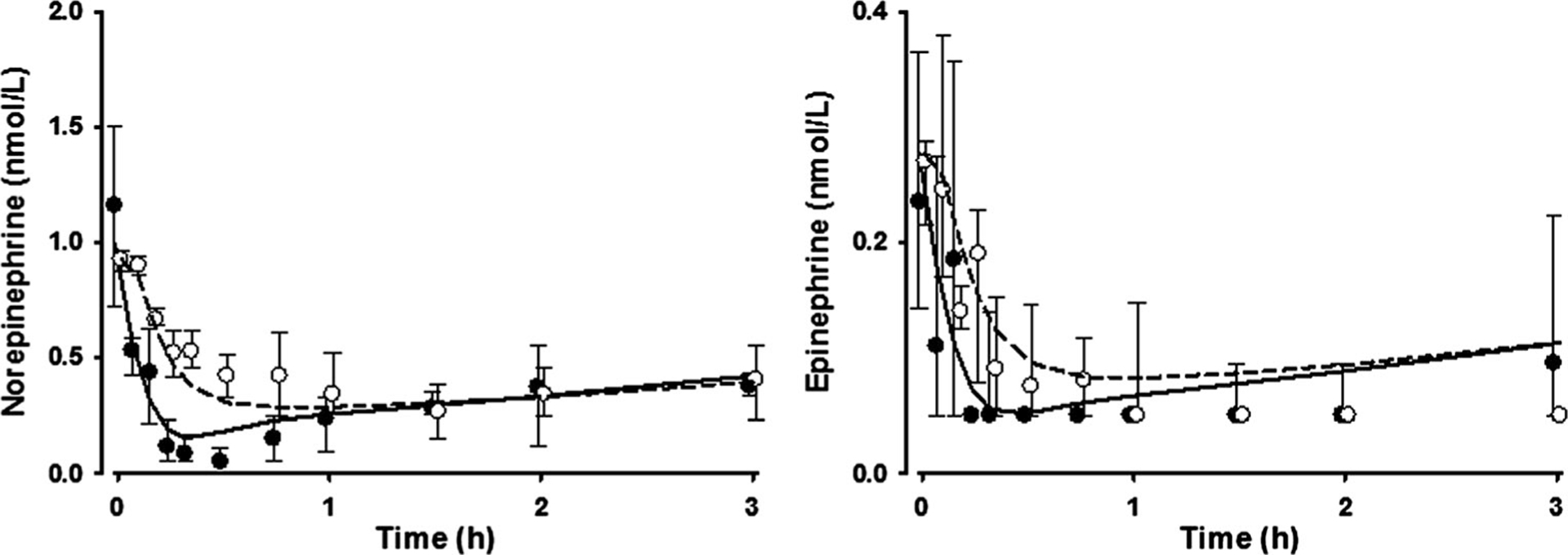

As shown in Fig. 3, both NE and E in plasma significantly decreased after both IV and IN dexmedetomidine administration. The parameters describing decrease of NE and E concentrations after dexmedetomidine are listed in Table 2. Dexmedetomidine as an α2-adrenoceptor agonist inhibits NE release. The IC50 of dexmedetomidine was 0.153 ng/mL for NEe and 0.166 ng/mL for Ep.

Fig. 3.

Norepinephrine and epinephrine concentrations in plasma after IV and IN administration of dexmedetomidine. The circles and whiskers represent the median values and interquartile ranges (closed for IV and open for IN). The lines represent population predictions (solid for IV and dashed for IN)

Table 2.

Pharmacodynamic parameters for dexmedetomidine effects on norepinephrine and epinephrine

| Parameter (unit) | Definition | Estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Norepinephrine | Epinephrine | ||

| R0 (nmol/L) | Baseline | 9.48 (43.5)a | 0.22 (14.4) |

| kd,s (h−1)a | Disposition rate constant | 10.2 (44.4)a | - |

| IC50 (ng/mL) | Drug concentration at one-half maximal inhibition of response | 0.153 (38.2) | 0.166 (11.9) |

| kd,p (h−1) | Disposition rate constant | 19.1 (82.2) | 3.67 (20.8) |

| Inter-individual variability | |||

| R0 (nmol/L) | - | 0.34 (37.6) [2] | |

| IC50 | 0.3 (88.0) [7] | - | |

| Residual variability | |||

| Additive error (nmol/L) | 0.072 (39.8) | - | |

| Proportional error | 0.356 (19.8) | 0.56 (11.5) | |

(%) RSE, [%] shrinkage

In noradrenergic nerve

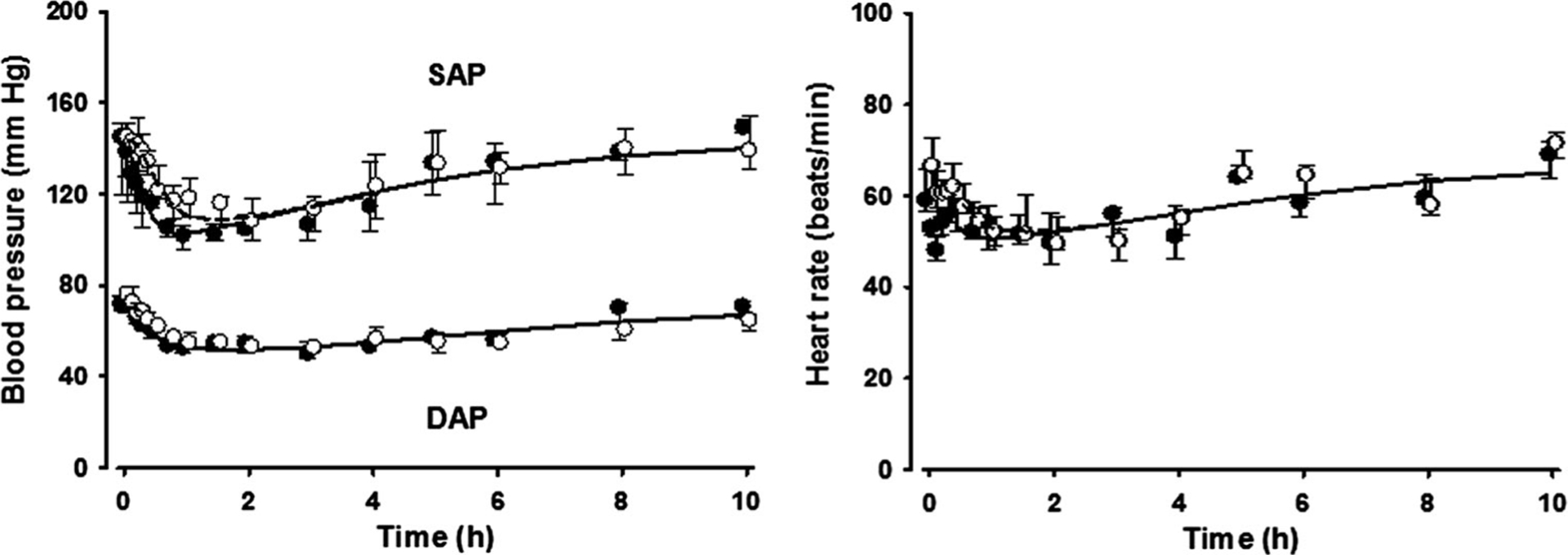

The BP declined to 76.6 mmHg for SAP and 47.3 mmHg for DAP with the decrease of NE concentrations followed by a partial recovery phase after about 2 h for both IV and IN doses. The observed BP (SAP and DAP) and HR were well described with the sigmoidal Emax model based on biophase concentrations of NE (Fig. 4). The PD parameter estimates for the effect of NE on BP (SAP and DAP) and HR are presented in Table 3. The EC50 was 8.24 nmol/L for SAP, 16.8 nmol/L for DAP, and 30.6 nmol/L for HR.

Fig. 4.

Blood pressure and heart rate measurements versus time. Symbols and lines are as defined in Fig. 3

Table 3.

Pharmacodynamic parameters for blood pressure and heart rate

| Parameter (unit) | Definition | Estimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic arterial pressure | Diastolic arterial pressure | Heart rate | ||

| Emax (mmHg or beats/min) | Maximum response | 203 | 140 | 191 |

| Emin (mmHg or beats/min) | Minimum response | 76.6 (40.9) | 47.3 (7.7) | 50.5 (7.5) |

| EC50 (nmol/L) | NEe at 50 % of Emax | 8.2 (42.6) | 16.8 (15.1) | 30.6 (44.1) |

| γ | Hill coefficient | 1.2 (36.9) | 1.9 (24.8) | 1.7 (49.2) |

| ke0 (h−1) | Biophase rate constant | 3.08 (10.5) | 1.39 (11.2) | 4.6 (74.8) |

| Inter-individual variability | ||||

| EC50 | 0.085 (84.3) [1] | 0.027 (64.0) [4] | 0.047 (64.8) [24] | |

| Residual variability | ||||

| Proportional error | 0.083 (4.2) | 0.090 (2.9) | 0.102 (12.9) | |

(%) RSE, [%] shrinkage

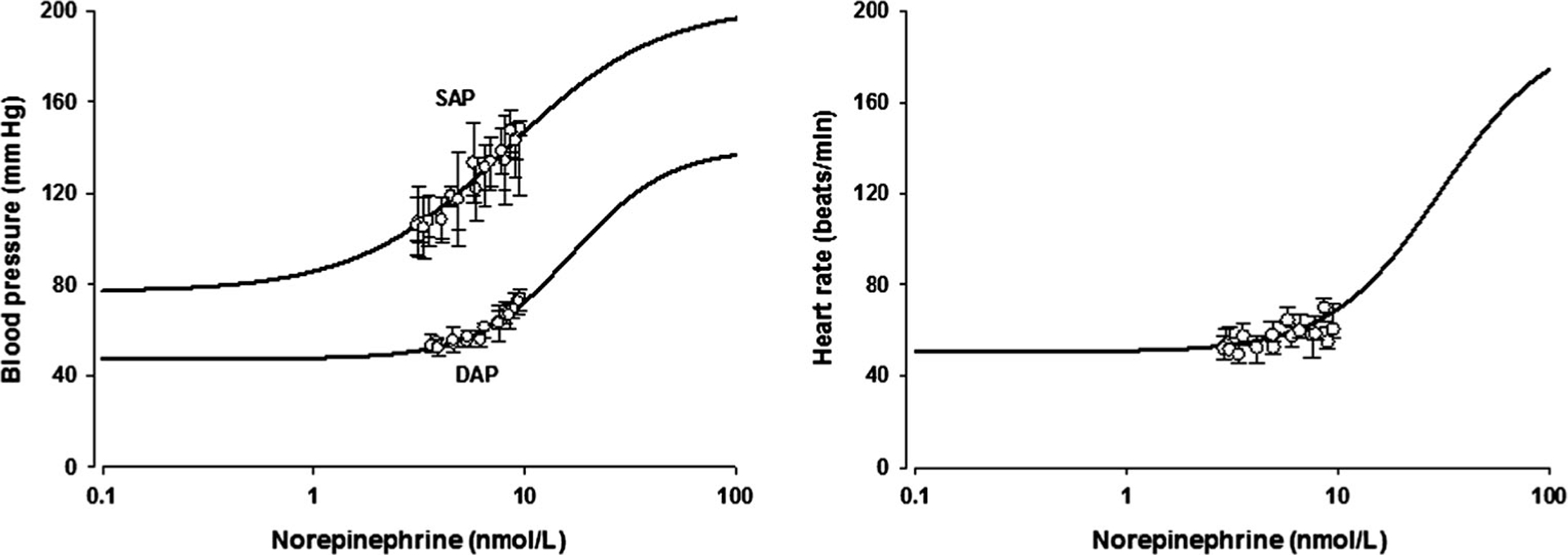

The pharmacological functions used to relate NE concentrations in the biophase to the BP and HR values are depicted graphically in Fig. 5. The fitted curve well captures both the known physiologic extremes as well as the present data with the parameters listed in Table 3.

Fig. 5.

Simulated profiles of blood pressure and heart rate vs. norepinephrine concentrations in the effect compartment using the fitted model and parameter estimates. The circles represent the median values and vertical lines are the interquartile ranges of the observed data in this study

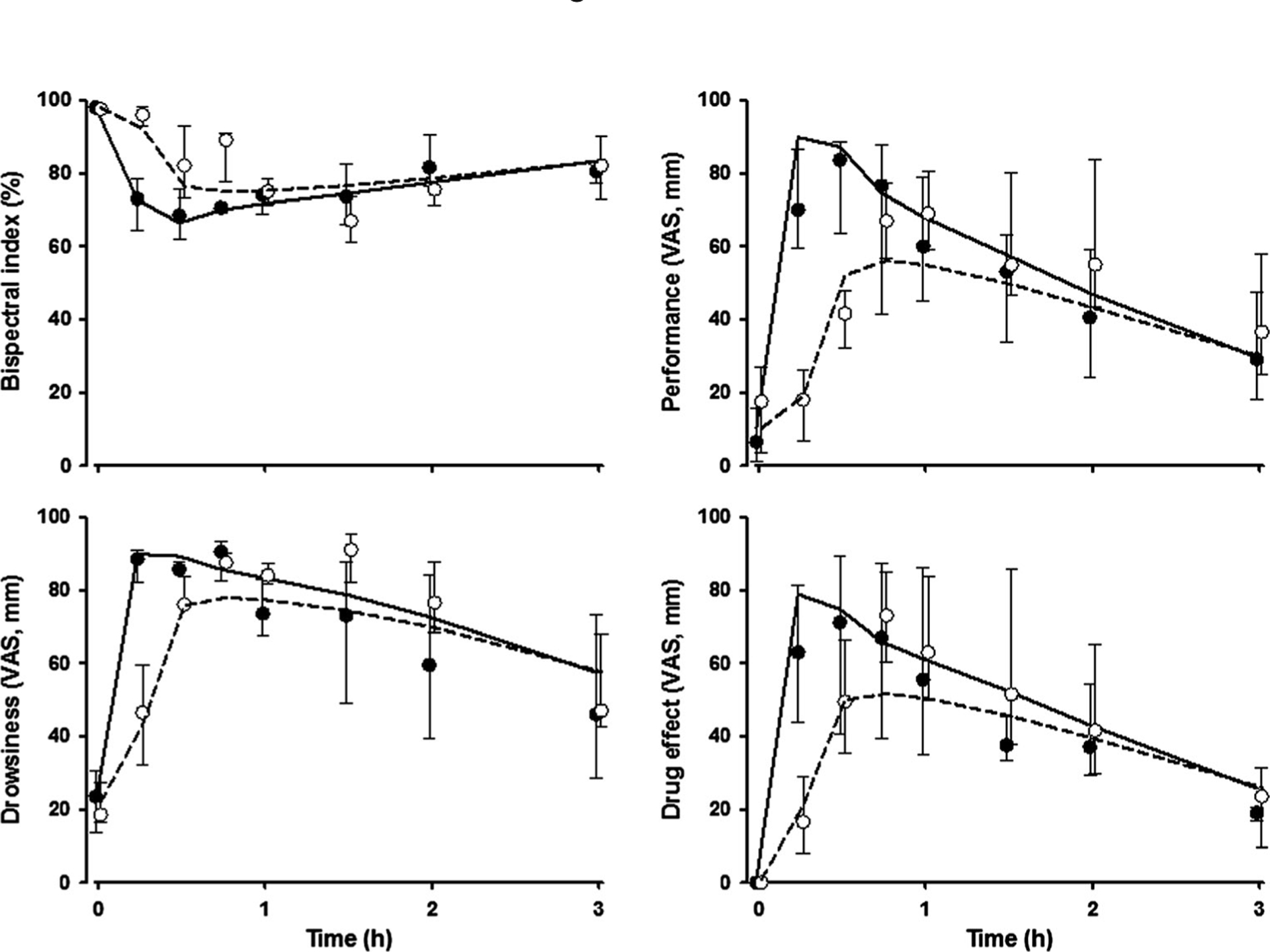

The time courses of observed and fitted subjective effects and bispectral index in healthy volunteers are shown in Fig. 6. These data showed large variability at each time point. The observed subjective effects and bispectral index were well captured with a sigmoidal Emax model controlled by NEe in an effect compartment. The PD parameter estimates are presented in Table 4. The subjective effects had relatively high shape factors (γ=3.1–4.2) that reflect acute changes in these responses as concentrations of NE decline. The bispectral index had responses of about 64.2 % at low concentrations of NE. The EC50 for subjective effects were similar (about 3.7 nmol/L), and also similar for the bispectral index (3.9 nmol/L).

Fig. 6.

Bispectral index and subjective effects versus time. Symbols and lines are as defined in Fig. 3

Table 4.

Pharmacodynamic parameters for bispectral index and subjective effects

| Parameter (unit) | Definition | Estimate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bispectral index | Subjective effects | ||||

| Performance | Drowsiness | Drug effect | |||

| E0 (%) | Baseline response | 64.2 (14.0) | 7.1 (14.0) | 9.5 (24.6) | 20.7 (67.6) |

| Emax (mm or %) | Maximum response | 33.7 (62.9) | 86.8 (7.3) | 71.3 (11.4) | 78.5 (19.4) |

| EC50 (nmol/L) | NEs at 50 % of Emax | 3.9 (26.9) | 3.3 (21.1) | 4.4 (18.5) | 3.5 (15.6) |

| γ | Shape factor | 3.1 (87.0) | 4.0 (80.6) | 4.2 (57.0) | 4.1 (22.7) |

| ke0 (h−1) | Biophase rate constant | 15.6 (31.1) | 18.2 (77.5) | 18.3 (61.2) | 36.5 (46.6) |

| Inter-individual variability | |||||

| EC50 | 0.038 (51.2) [20] | 0.119 (41.0) [0.4] | 0.074 (51.9) [6] | 0.051 (81.3) [5] | |

| Residual variability | |||||

| Additive error (mm or %) | 7.99 (11.1) | 6.05 (45.1) | 11.70 (13.4) | 1.66 (13.6) | |

| Proportional error | - | 0.18 (36.7) | - | 0.38 (9.9) | |

(%) RSE, [%] shrinkage

Discussion

The population PK of dexmedetomidine is well described by a two-compartment model with zero-order input for IV and with first-order absorption and lag time for IN administration. A two-compartment PK model was used to assess dexmedetomidine disposition in most previous studies [10, 31, 32]. The IN absorption of dexmedetomidine was slightly delayed and had about 90 % lower Cmax than IV administration. The volume of distribution at a steady state was estimated as 89.3 L. This is smaller compared to a previous report [10]. However, the clearance (44 L/h) estimated is within the range (31–57 L/h) found earlier [8, 13]. The bioavailability of IN dexmedetomidine was estimated as 82 %. This is similar to a previous report for buccal administration [10].

Dexmedetomidine has diverse effects according to the expression of α2-adrenoceptor subtypes in target cells [3]. Dexmedetomidine binds to α2-adrenoceptors on target cells with high selectivity resulting in inhibition of catecholamine release in the brain and in the peripheral sympathetic nerves. The process involves activating G proteins leading to inhibition of adenylate cyclase and voltage-gated Ca2+ currents [9, 33, 34]. Plasma concentrations of NE and E declined markedly after dexmedetomidine [7, 35]. This suggests that dexmedetomidine, an α2-adrenoceptor agonist, can inhibit catecholamine release almost completely. We assumed that the NE release is identical in the brain and in the peripheral sympathetic nerves, and release of NE and E from nerves is constant. The inhibition of release was captured well with an indirect response model [36]. Dexmedetomidine, the pharmacologically active enantiomer of medetomidine, exhibited IC50 values of 0.153 ng/mL or 0.77 nM. With 6 % unbound drug in plasma, the free IC50 is about 12.8 nM, similar to the in vitro Ki values reported earlier [37]. Previous studies giving IV 3H-NE in healthy volunteers revealed bi-exponential disposition kinetics with a distribution half-life of 2 min and later half-life of 33 min [38]. Our kd value of 19.1 h−1 yields a half-life of about 2.2 min. A two-compartment model for NE was not attempted, but would be a reasonable next step.

The observed BP (SAP and DAP) and HR were linked via a sigmoidal Emax function using the concentrations of NE in a biophase or transduction compartment. The EC50 value of HR was higher than those for BP. The PD modeling of BP and HR required use of maximum BP and HR values obtained from the literature. The normal range of HR at rest is 60~80 beats/min in adults. The minimum HR was about 50 beats/min in this study. Plasma concentrations of NE significantly increase with severe exercise. The maximum HR in healthy young men is over 200 beats/min [39]. Thus, the normal range of HR at rest is not the median (about 120) of HRmin and HRmax, nor is it a typical baseline value as commonly employed in PD modeling. The relationships for BP and HR versus NE in the effect compartment were simulated using the fitted model and parameter estimates as shown in Fig. 5. Our model, which considered the possible maximum HR, is a rational and unique relationship in assessing PD. It allows for NE to increase BP and HR with higher concentrations and to decrease BP and HR with drugs such as dexmedetomidine.

The IV bolus dosing of α2-adrenoceptor agonists usually causes a biphasic cardiovascular response depending on the concentration. After transient hypertension, arterial pressure falls below the baseline; the hypertensive phase can be avoided by a slow infusion [8, 37]. The IN administration may avoid these acute hemodynamic changes in patients requiring light sedation similar to IM doses of dexmedetomidine [8]. Indeed, the IN application of dexmedetomidine has been used successfully as premedication in children [40].

The bispectral index and subjective effects was modeled with sigmoidal Emax function that includes a baseline value using the concentrations of NE in a biophase or transduction compartment. The bispectral index decreased to 33.7 % from baseline response along with the decrease of NE. Initial responses of subjective effects and bispectral index were significantly different between IV and IN dosing. Drug effects occur sooner for IV compared with IN doses. Having both IV and IN doses with differing PK profiles augmented our ability to resolve model parameters as did the utilization of upper and lower bounds for all of the effects measured. Interestingly, the range of NE EC50 values showed highest sensitivity of the subjects for all of the CNS effects (about 3.7 nmol/L, Table 4), while the range of NE EC50 values showed lesser sensitivity for the cardiovascular effects (8.2–16.8 nmol/L for BP, 30.6 nmol/L for HR, Table 3). The onset of the latter is slowed by the time required for reduction in NE concentrations as well as the biophase distribution.

The CNS effects of dexmedetomidine were better captured after IV than after IN dosing (Fig. 6). The original purpose of this study was to compare the PK and efficacy of IN dexmedetomidine and, indeed, demonstrated good IN bioavailability (F = 82 %). Most of the CNS effects of dexmedetomidine after IN dosing were greater than the model predictions after 0.75 h. It has been proposed that IN dosing can result in enhanced brain delivery, which might account for our findings [41]. On the other hand, studies with IN midazolam [42] involved PK/PD modeling where IV and IN doses could be fitted jointly.

Covariates such as age, weight, height, and BMI did not have any obvious effects on the PK/PD parameters of dexmedetomidine, probably because the study was conducted in a relatively homogeneous population of healthy young male volunteers. The inter-individual variability of parameters have relatively high RSE values, this may be due to the small number of subjects. Although circadian rhythms may affect BP and HR, our studies include relatively short time data insufficient to reflect such rhythms. However, BP and HR in the initial phase show abrupt decreases after dexmedetomidine administration. Studies from a more diverse population with control groups may allow more meaningful and accurate PK/PD modeling of dexmedetomidine. Also, we assumed that there is no between occasion variability in the parameters.

In conclusion, PK profiles for both IV and IN doses of dexmedetomidine were well fitted using a two-compartment PK model. The mechanism-based PK/PD model of dexmedetomidine had several unique features. An indirect response model for inhibition of NE allowed utilization of endogenous mediators which controlled the diverse effects of the drug. A biophase or transduction step was needed for NE affecting BP (SAP and DAP) and HR presumably either reflecting their access to the heart and blood vessels or receptor binding and signaling. The pharmacologic function allowed for a wide range of physiologic values of BP and HR even though the data reflected moderate reductions. Also, the alteration of subjective effects and bispectral index by NE in biophase sufficed. The population-based models allowed some quantitative understanding of inter- and intra-individual variability of dexmedetomidine PK and PD. These mechanism-based population PK/PD models of dexmedetomidine provide comprehensive quantitation of multiple actions of an important α2-adrenoceptor agonist drug used for perioperative and intensive care sedation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH Grants 57980 and 24211.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00228-015-1913-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chrysoslomou C, Schmitt GG (2008) Dexmedetomidine: sedation, analgesia and beyond. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 4:619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Limbird LE (1988) Receptors linked to inhibition of adenylate cyclase: additional signaling mechanisms. FASEB J 2:2686–2695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brede M, Philipp M, Knaus A, Muthig V, Hein L (2004) Alpha2-adrenergic receptor subtypes - novel functions uncovered in gene-targeted mouse models. Biol Cell 96:343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belleville JP, Ward DS, Bloor BC, Maze M (1992) Effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine in humans. I. Sedation, ventilation, and metabolic rate. Anesthesiology 77:1125–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu YW, Cortinez LI, Robertson KM, Keifer JC, Sum-Ping ST, Moretti EW, Young CC, Wright DR, Macleod DB, Somma J (2004) Dexmedetomidine pharmacodynamics: part I: crossover comparison of the respiratory effects of dexmedetomidine and remifentanil in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology 101:1066–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekker A, Sturaitis MK (2005) Dexmedetomidine for neurological surgery. Neurosurgery 57(1 Suppl):1–10, discussion 11–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloor BC, Ward DS, Belleville JP, Maze M (1992) Effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine in humans. II. Hemodynamic changes. Anesthesiology 77:1134–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyck JB, Maze M, Haack C, Vuorilehto L, Shafer SL (1993) The pharmacokinetics and hemodynamic effects of intravenous and intramuscular dexmedetomidine hydrochloride in adult human volunteers. Anesthesiology 78:813–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gertler R, Brown HC, Mitchell DH, Silvius EN (2001) Dexmedetomidine: a novel sedative-analgesic agent. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 14:13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anttila M, Penttila J, Helminen A, Vuorilehto L, Scheinin H (2003) Bioavailability of dexmedetomidine after extravascular doses in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 56:691–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhana N, Goa KL, McClellan KJ (2000) Dexmedetomidine. Drugs 59:263–268, discussion 269–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su F, Nicolson SC, Gastonguay MR, Barrett JS, Adamson PC, Kang DS, Godinez RI, Zuppa AF (2010) Population pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine in infants after open heart surgery. Anesth Analg 110:1383–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iirola T, Ihmsen H, Laitio R, Kentala E, Aantaa R, Kurvinen JP, Scheinin M, Schwilden H, Schüttler J, Olkkola KT (2012) Population pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine during long-term sedation in intensive care patients. Br J Anaesth 108:460–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potts AL, Anderson BJ, Holford NH, Vu TC, Warman GR (2010) Dexmedetomidine hemodynamics in children after cardiac surgery. Paediatr Anaesth 20:425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bol C, Danhof M, Stanski DR, Mandema JW (1997) Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic characterization of the cardiovascular, hypnotic, EEG and ventilatory responses to dexmedetomidine in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 283:1051–1058 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenach JC, Shafer SL, Bucklin BA, Jackson C, Kallio A (1994) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intraspinal dexmedetomidine in sheep. Anesthesiology 80:1349–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iirola T, Vilo S, Manner T, Aantaa R, Lahtinen M, Scheinin M, Olkkola KT (2011) Bioavailability of dexmedetomidine after intranasal administration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 67:825–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheinin M, Karhuvaara S, Ojala-Karlsson P, Kallio A, Koulu M (1991) Plasma 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG) and 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) are insensitive indicators of alpha 2-adrenoceptor mediated regulation of norepinephrine release in healthy human volunteers. Life Sci 49:75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigl JC, Chamoun NG (1994) An introduction to bispectral analysis for the electroencephalogram. J Clin Monit 10:392–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bond AJ, Lader MH (1974) The use of analogue scales in rating subjective feelings. Br J Med Psychol 47:211–218 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linares OA, Jacquez JA, Zech LA, Smith MJ, Sanfield JA, Morrow LA, Rosen SG, Halter JB (1987) Norepinephrine metabolism in humans. Kinetic analysis and model. J Clin Invest 80:1332–1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilsted J, Christensen NJ, Madsbad S (1983) Whole body clearance of norepinephrine. The significance of arterial sampling and of surgical stress. J Clin Invest 71:500–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wohlfart B, Farazdaghi GR (2003) Reference values for the physical work capacity on a bicycle ergometer for men – a comparison with a previous study on women. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 23: 166–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Heart Association (2012) Understanding Blood Pressure Readings.: American Heart Association; Accessed 4 April [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox SM 3rd, Naughton JP, Haskell WL (1971) Physical activity and the prevention of coronary heart disease. Ann Clin Res 3:404–432 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller WC, Wallace JP, Eggert KE (1993) Predicting max HR and the HR-VO2 relationship for exercise prescription in obesity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 25:1077–1081 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka H, Fukumoto S, Osaka Y, Ogawa S, Yamaguchi H, Miyamoto H (1991) Distinctive effects of three different modes of exercise on oxygen uptake, heart rate and blood lactate and pyruvate. Int J Sports Med 12:433–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robergs RA, Landwehr R (2002) The surprising history of the “HRmax=220 - age” equation. J Exerc Physiol (Online) 5:1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beal SL, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann AJ, and Bauer RJ (eds) NONMEM 7.3.0 Users Guides. (1989–2013). ICON Development Solutions, Hanover, MD [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hooker AC, Staatz CE, Karlsson MO (2007) Conditional weighted residuals (CWRES): a model diagnostic for the FOCE method. Pharm Res 24:2187–2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Wolf AM, Fragen RJ, Avram MJ, Fitzgerald PC, Rahimi-Danesh F (2001) The pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine in volunteers with severe renal impairment. Anesth Analg 93:1205–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dutta S, Lal R, Karol MD, Cohen T, Ebert T (2000) Influence of cardiac output on dexmedetomidine pharmacokinetics. J Pharm Sci 89:519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langer SZ (1976) The role of alpha- and beta-presynaptic receptors in the regulation of noradrenaline release elicited by nerve stimulation. Clin Sci Mol Med Suppl 3:423s–426s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cotecchia S, Kobilka BK, Daniel KW, Nolan RD, Lapetina EY, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Regan JW (1990) Multiple second messenger pathways of alpha-adrenergic receptor subtypes expressed in eukaryotic cells. J Biol Chem 265:63–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kallio A, Scheinin M, Koulu M, Ponkilainen R, Ruskoaho H, Viinamäki O, Scheinin H (1989) Effects of dexmedetomidine, a selective alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist, on hemodynamic control mechanisms. Clin Pharmacol Ther 46:33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dayneka N, Garg V, Jusko WJ (1993) Comparison of four basic models of indirect pharmacodynamic responses. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 21:457–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Zwieten PA, Chalmers JP (1994) Different types of centrally acting antihypertensives and their targets in the central nervous system. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 8:787–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esler M, Jackman G, Bobik A, Leonard P, Kelleher D, Skews H, Jennings G, Korner P (1981) Norepinephrine kinetics in essential hypertension. Defective neuronal uptake of norepinephrine in some patients. Hypertension 3:149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowell LB, Brengelmann GL, Freund PR (1987) Unaltered norepinephrine-heart rate relationship in exercise with exogenous heat. J Appl Physiol 62:646–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuen VM, Hui TW, Irwin MG, Yao TJ, Wong GL, Yuen MK (2010) Optimal timing for the administration of intranasal dexmedetomidine for premedication in children. Anaesthesia 65: 922–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jogani V, Jinturkar K, Vyas T, Misra A (2008) Recent patents review on intranasal administration for CNS drug delivery. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul 2:25–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wermeling DP, Record KA, Kelly TH, Archer SM, Clinch T, Rudy AC (2006) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a new intranasal midazolam formulation in healthy volunteers. Anesth Analg 103:344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.