Abstract

Background: Prurigo nodularis (PN) is an intensely pruritic skin condition of considerable morbidity. However, the pathogenesis of PN and its association with underlying neuropathy is unclear. Objective: We sought to investigate the association between PN and etiologies of peripheral neuropathy. Methods: A cross-sectional analysis of adult patients (≥18-year-old) with PN, AD, and Psoriasis at the Johns Hopkins Health System over a six-year period (January 2013–January 2019) was performed. The strength of association with etiologies of peripheral neuropathy were compared to a control cohort of individuals without PN, as well as those with AD or psoriasis. Results: A total of 1122 patients with PN were compared to 10,390 AD patients, 15,056 patients with psoriasis, and a control cohort of 4,949,017 individuals without PN, with respect to 25 comorbidities associated with peripheral neuropathies. Limitations: Comparisons between peripheral neuropathies and PN represent associations but are not causal relationships. Conclusion: Prurigo nodularis is strongly associated with peripheral neuropathies, suggesting a role for neural dysregulation in pathogenesis.

Keywords: prurigo nodularis, nodular prurigo, pruritus, itch, neuropathy

1. Introduction

Prurigo nodularis (PN) is a chronic skin condition characterized by intensely pruritic nodules and hyperkeratotic lesions. Lesions are distributed symmetrically with involvement of extensor surfaces of the extremities. The intractable pruritus of PN is a significant contributor of morbidity for patients and commonly presents in the context of known pruritic conditions [1]. It is associated with other dermatologic conditions, such as atopic dermatitis and other systemic diseases [2]. Examples of systemic diseases associated with PN include liver or kidney dysfunction, hyperthyroidism, metabolic dysfunction, inflammatory processes, psychological factors, and malignancy [3,4,5]. The underlying mechanism of how these conditions contribute to the pathogenesis of PN remains unclear; however, neural dysregulation is thought to play a central role.

Recent studies have studied intraepidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD) as an important contributor to chronic pruritus and in small fiber neuropathies [6,7]. Patients with PN are observed to have decreased IENFD as compared to healthy individuals [7]. Furthermore, there is a significant reduction in IENFD in lesional PN skin, which may be due to prolonged scratching, but also in non-lesional PN [5]. Indeed, the resolution of pruritus is associated with the recovery of dermal nerve fiber density [6]. Cellular changes observed in patients with PN include increased concentrations of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in the nerve fibers of PN patients [8]. Whether these neurophysiological changes are markers of an underlying neuropathies or are a result of the intractable pruritus remains controversial [9]. However, treatments commonly used to treat neuropathic pain have been shown to benefit PN. Agents such as gabapentin and pregabalin have been successfully used to treat patients with PN [10,11,12]. Thalidomide has also been successfully used to treat refractory cases of prurigo nodularis [13,14].

With the evidence surrounding a neural origin of PN unclear, we sought to understand the association between PN and peripheral neuropathies. Furthermore, we conducted a cross-sectional investigation in our health system, comparing patients with PN to individuals with psoriasis, and those with atopic dermatitis.

2. Materials and Methods

An association between PN and peripheral neuropathies was investigated by using the Johns Hopkins Health System (JHHS) electronic medical record system, EPIC. The JHHS is a representative collection of approximately 25–30 million individuals located in a 200-mile area within Maryland and its neighboring states and is inclusive of individuals traveling from other countries to the JHHS. Institutional review board approval was not required, as only anonymous, aggregate-level data were used.

A cross-sectional study was performed of patients aged 18 years and older seen at JHHS between 1 January 2013 and 1 January 2019 (n = 4,950,139). EPIC Slicer Dicer was used to collect anonymized aggregate-level data; consequently, IRB approval was waived. SNOMED CT search terms were applied to separately identify patients with PN, atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, or patients without PN. Disease-specific search terms were then applied to identify the prevalence of patients within each group diagnosed with each selected peripheral-neuropathy-related condition. Odds ratios were calculated by comparing the prevalence of patients with PN and each comorbidity to the prevalence of patients in each group with the same comorbidity. Then, p-values were calculated, using chi-squared tests with one degree of freedom. To account for multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni-corrected p-value was applied. Associations were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

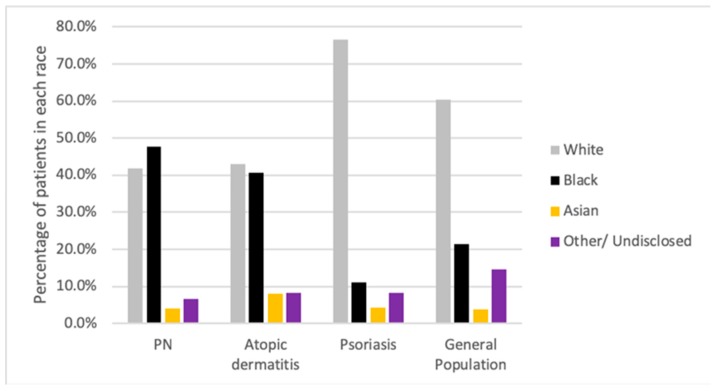

A total of 1122 adult patients with PN, 10,390 AD patients, and 15,056 patients with psoriasis were identified over the six-year period (Figure 1). A control cohort consisting of 4,949,017 individuals without PN was used. In the general population, there was a predominance of Caucasians (61.3%), with African American individuals only representing 21.3% of the patients within the JHHS. Similarly, Caucasians represented over 76.6% of the psoriasis group. In comparison, PN and AD cohorts had differing representative populations. The PN cohort was composed of 41.9% Caucasian and 47.6% African American individuals. Similarly, the AD cohort had 43% and 40.5% of Caucasian and African American patients, respectively.

Figure 1.

Racial backgrounds of all patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of prurigo nodularis (PN), atopic dermatitis (AD), or psoriasis, and within the general population who presented to the Johns Hopkins Hospital System between 1 January 2013 and 1 January 2019.

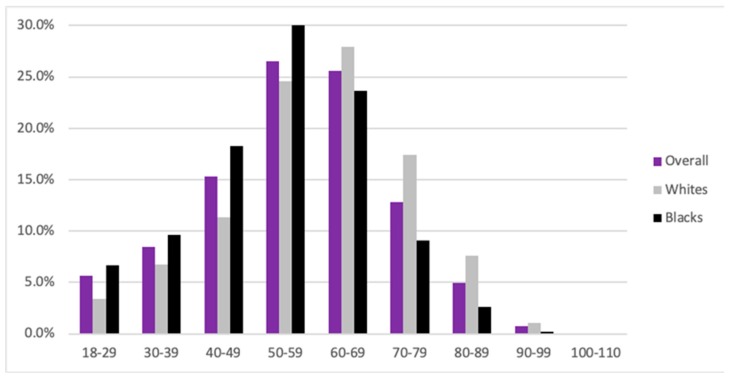

Within the PN study cohort, the proportion of males and females was similar as compared to the general population, with 52% females and 48% males within the PN cohort, and 54.2% females and 45.5% males within the general population. The mean age of PN patients was 56, similar to the general population (56) and the psoriasis cohort (55) (Figure 2). Individuals with atopic dermatitis were comparatively younger, with a mean age of 45. The prevalence of PN increased with age, with the peak prevalence seen between 50 and 59 years of age and composing 26.5% of our cohort. A total of 67.4% of all patients with PN were between 40 and 69 years of age, with individuals between the years of 50 and 59 composing 26.5% of the cohort.

Figure 2.

Age distribution of patients with prurigo nodularis (PN) overall, in black and in white patients.

3.2. Association of Prurigo Nodularis with Conditions Known to Feature Peripheral Neuropathies

Individuals with PN were more likely to have comorbidities associated with peripheral neuropathies as compared to the general population (Table 1). The most common comorbidities seen in patients with PN were statin use (37.34%), diabetes mellitus (26.38%), chronic kidney disease (16.04%), human influenza virus (HIV, 13.37%), metronidazole use (12.39%), and hypothyroidism (11.05%). All the comorbidities analyzed were significantly more common in the PN group, with the exception of small-cell carcinoma (p = 0.09). Of the significant comorbidities, borreliosis (Lyme disease) was weakly associated with PN (OR: 3.6, IQR 1.5–8.6, p < 0.00001). In contrast, patients with PN were 58 times more likely to have HIV as compared to the general population (OR: 58, IQR 48.8–68.9, p < 0.00001). External agents associated with comorbidities of peripheral neuropathies include the use of dapsone, alcohol use, statins, and metronidazole (p < 0.00001). Both cobalamin deficiency and folic acid deficiency were associated with peripheral neuropathies in patients with PN. Lastly, inflammatory processes, chronic kidney disease, and neoplasms were associated strongly with PN, including vasculitis (p < 0.000001), chronic kidney disease (OR 16.3; 95% CI 13.9–19.2; p < 0.00001), and primary malignant neoplasms (p < 0.00001). Other conditions, including diabetes mellitus, hyperpituitarism, hypothyroidism, and the presence of myxedema, carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar nerve entrapment, amyloidosis, vasculitis, and phlebitis, were associated with PN.

Table 1.

Absolute number, percentage, odds ratios, and p-values of all patients 18 years and older with PN and various comorbid conditions, as compared with those of patients 18 and older with AD, with psoriasis, or within the general population (without PN) who were seen at the JHHS between 1 January 2013 and 1 January 2019.

| Comorbidity | PN, n (%) | AD, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Psoriasis, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Gen Pop, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral neuropathies | 308(27.45) | 1673(16.1) | 1.97(1.71–2.27) | <0.002 | 2759(18.32) | 1.69(1.47–1.94) | <0.002 | 150,325(3.04) | 12.08(10.59–13.77) | <0.002 |

| Focal–multifocal neuropathies | ||||||||||

| Amyloidosis | 12(1.07) | 31(0.3) | 3.61(1.85–7.05) | <0.002 | 32(0.21) | 5.08(2.61–9.88) | <0.002 | 2234(0.05) | 23.94(13.53–42.35) | <0.002 |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | 54(4.81) | 397(3.82) | 1.27(0.95–1.7) | 0.10377 | 522(3.47) | 1.41(1.06–1.88) | 0.01893 | 22,079(0.45) | 11.28(8.58–14.83) | <0.002 |

| DM | 296(26.38) | 1167(11.23) | 2.83(2.45–3.28) | <0.002 | 2648(17.59) | 1.68(1.46–1.93) | <0.002 | 177,323(3.58) | 9.64(8.44–11.01) | <0.002 |

| Hyperpituitarism | 6(0.53) | 37(0.36) | 1.5(0.63–3.57) | 0.35138 | 38(0.25) | 2.12(0.9–5.04) | 0.07978 | 3268(0.07) | 8.14(3.64–18.16) | <0.002 |

| Myxedema | 5(0.45) | 15(0.14) | 3.1(1.12–8.53) | 0.02133 | 27(0.18) | 2.49(0.96–6.48) | 0.05277 | 1169(0.02) | 18.95(7.86–45.69) | <0.002 |

| Phlebitis | 26(2.32) | 122(1.17) | 2(1.3–3.06) | <0.002 | 168(1.12) | 2.1(1.38–3.19) | <0.002 | 7395(0.15) | 15.85(10.74–23.4) | <0.002 |

| Ulnar nerve entrapment | 17(1.52) | 74(0.71) | 2.14(1.26–3.65) | 0.00391 | 76(0.5) | 3.03(1.79–5.15) | <0.002 | 3546(0.07) | 21.46(13.27–34.68) | <0.002 |

| Vasculitis | 38(3.39) | 208(2) | 1.72(1.21–2.44) | 0.00231 | 302(2.01) | 1.71(1.22–2.41) | <0.002 | 13,241(0.27) | 13.07(9.45–18.07) | <0.002 |

| Chronic axonal neuropathies | ||||||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 69(6.15) | 202(1.94) | 3.3(2.5–4.38) | <0.002 | 462(3.07) | 2.07(1.6–2.69) | <0.002 | 33,073(0.67) | 9.74(7.63–12.43) | <0.002 |

| Borreliosis | 5(0.45) | 63(0.61) | 0.73(0.29–1.83) | 0.50450 | 141(0.94) | 0.47(0.19–1.16) | 0.09351 | 62,20(0.13) | 3.56(1.48–8.57) | 0.00250 |

| CKD | 180(16.04) | 446(4.29) | 4.26(3.54–5.13) | <0.002 | 950(6.31) | 2.84(2.39–3.37) | <0.002 | 57,268(1.16) | 16.32(13.91–19.15) | <0.002 |

| Cobalamin deficiency | 31(2.76) | 204(1.96) | 1.42(0.97–2.08) | 0.07200 | 383(2.54) | 1.09(0.75–1.58) | 0.65366 | 13,782(0.28) | 10.17(7.12–14.55) | <0.002 |

| Dapsone | 48(4.28) | 132(1.27) | 3.47(2.48–4.86) | <0.002 | 96(0.64) | 6.97(4.9–9.9) | <0.002 | 5420(0.11) | 40.76(30.49–54.5) | <0.002 |

| Folic acid deficiency | 5(0.45) | 14(0.13) | 3.32(1.19–9.23) | 0.01480 | 30(0.2) | 2.24(0.87–5.79) | 0.08659 | 930(0.02) | 23.82(9.87–57.47) | <0.002 |

| HIV infection | 150(13.37) | 185(1.78) | 8.51(6.8–10.66) | <0.002 | 144(0.96) | 15.98(12.6–20.27) | <0.002 | 13,137(0.27) | 57.98(48.78–68.92) | <0.002 |

| Hypothyroidism | 124(11.05) | 844(8.12) | 1.41(1.15–1.72) | <0.002 | 2066(13.72) | 0.78(0.64–0.95) | 0.01169 | 113,182(2.29) | 5.31(4.4–6.4) | <0.002 |

| Metronidazole | 139(12.39) | 1216(11.7) | 1.07(0.88–1.29) | 0.49875 | 1098(7.29) | 1.8(1.49–2.17) | <0.002 | 69,631(1.41) | 9.91(8.3–11.84) | <0.002 |

| NSCLC | 3(0.27) | 9(0.09) | 3.09(0.84–11.44) | 0.07466 | 33(0.22) | 1.22(0.37–3.99) | 0.74091 | 2234(0.05) | 5.94(1.91–18.45) | <0.002 |

| Phenytoin | 2(0.18) | 1(0.01) | 18.55(1.68–204.76) | <0.002 | 2(0.01) | 13.44(1.89–95.52) | <0.002 | 1039(0.02) | 8.5(2.12–34.09) | <0.002 |

| PMN | 94(8.38) | 432(4.16) | 2.11(1.67–2.66) | <0.002 | 894(5.94) | 1.45(1.16–1.81) | <0.002 | 73,237(1.48) | 6.09(4.93–7.52) | <0.002 |

| PMN of Lung | 6(0.53) | 30(0.29) | 1.86(0.77–4.47) | 0.16086 | 83(0.55) | 0.97(0.42–2.23) | 0.94261 | 7227(0.15) | 3.68(1.65–8.2) | <0.002 |

| PMN of Ovary | 2(0.18) | 4(0.04) | 4.64(0.85–25.34) | 0.05135 | 4(0.03) | 6.72(1.23–36.73) | 0.01090 | 481(0.01) | 18.37(4.58–73.76) | <0.002 |

| Small-cell carcinoma | 1(0.09) | 4(0.04) | 2.32(0.26–20.74) | 0.43939 | 14(0.09) | 0.96(0.13–7.3) | 0.96736 | 948(0.02) | 4.66(0.65–33.12) | 0.09051 |

| Statins | 419(37.34) | 1999(19.24) | 2.5(2.2–2.85) | <0.002 | 4748(31.54) | 1.29(1.14–1.47) | <0.002 | 361,855(7.31) | 7.56(6.69–8.53) | <0.002 |

| Waldenstrom’s disease | 1(0.09) | 3(0.03) | 3.09(0.32–29.72) | 0.30358 | 5(0.03) | 2.69(0.31–23.01) | 0.34799 | 293(0.01) | 15.07(2.11–107.42) | <0.002 |

Data are for all patients aged 18 years or older, including 1122 patients with prurigo nodularis (PN), 10,390 patients with AD, 15,056 patients with psoriasis, and 4,949,017 patients in the general population (excluding those with PN). PMN; primary malignant neoplasm; JHHS, Johns Hopkins Health System; CKD, chronic kidney disease; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; n/a, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

We next examined whether significant differences existed between patients with PN, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis (Table 1). Among the many differences, patients with PN were more likely to have chronic kidney disease and HIV as compared to both comparator groups (p < 000001). However, there were no differences with malignant processes and metabolic conditions, including hyperpituitarism and primary malignant neoplasms, such as small-cell carcinoma and non-small-cell carcinoma. In comparison to atopic dermatitis, no significant differences were observed between carpal tunnel syndrome, use of metronidazole, folic acid deficiency, or hypothyroidism. When comparing the PN cohort to the psoriasis cohort, patients with PN were more likely to have comorbidities associated with peripheral neuropathies, with the exception of myxedema, borreliosis, PMN, folic acid deficiency, and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia.

4. Discussion

The etiology of PN is complex, with both local and systemic disease contributing to the intense pruritus characteristic of the disease [15]. While underlying dermatological conditions, systemic disease, and mood disturbances have been previously associated with PN [16], a limited number of studies have been conducted investigating a neuropathic etiology of PN. Herein, we observed a significant association between PN and comorbidities of peripheral neuropathies. Many of the comorbidities examined, including chronic kidney disease, type-2 diabetes mellitus, and HIV infections, likely contribute both through their association with pruritus and the development of peripheral neuropathies [17]. Furthermore, patients with PN were more likely to have HIV as compared to patients with AD or psoriasis and may be accounted for by the role of HIV as a contributor to severe systemic pruritus [15,18].

Notably, exogenous agents and the association of drug therapies and peripheral neuropathies were observed within our cohort. The use of statins and metronidazole were both more likely to be seen in patients with PN. Evidence suggests that pruritus has been reported in up to 16% of cases associated with statins [19]. Furthermore, both statins and dapsone have been reported in the literature, for their association with peripheral neuropathies [20,21]. Metronidazole is uncommonly associated with pruritus, though it has been associated with the development of peripheral neuropathies in patients exposed to extended high-dose treatment courses [22]. The use of low-dose metronidazole has been reported in several case reports for the management of PN [23]. Lastly, there is an association between patients with PN and depression, anxiety, and greater anxiolytic use [16]. Recent evidence comparing patients with psoriasis and PN found no differences in the psychological profile with respect to the prevalence of anxiety, depression, or somatoform disorders [24]. These findings may account for the increased likelihood of alcohol abuse seen within our PN cohort and its known association with peripheral neuropathies. More importantly, our findings further emphasize the need for increased awareness and consideration of early referral for psychodynamic intervention on behalf of these patients.

Differences existing between PN, AD, and psoriasis were observed within our study. Interestingly, these differences, although in part likely due to different pathophysiology of these conditions, may also be explained by the difference in burden caused by the pruritus. A recent study examining the burden of pruritus amongst inflammatory dermatoses found that patients with PN were significantly more bothered by evening and nighttime pruritus and reported more significant impairment in quality of life as compared to patients with psoriasis and AD, despite the association of AD and PN [25,26].

We also found that PN was significantly associated with carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar nerve entrapment, myxedema, hyperpituitarism, amyloidosis, vasculitis, and phlebitis, all of which are novel, to the best of our knowledge, with the exception of amyloidosis [27]. Malignancy was significantly associated with the PN as compared to the general population, likely due to its contributions to pruritus. Recent studies have identified that patients with PN are more likely to have been diagnosed with a malignancy as compared to the general population [28]. However, given the limited number of patients with small-cell carcinoma, it is possible that its lack of association with PN may have represented a statistical anomaly due to limited sample size.

As a cross-sectional analysis, our comparisons are limited to establishing correlations and not causative relationships between PN and peripheral neuropathies. In addition, the temporality between peripheral neuropathies and exposure to the underlying etiology is not captured by our analysis. It is likely that the pathogenesis of PN and peripheral neuropathies is multifactorial and includes variables not accounted for in our analysis. Lastly, the data are representative of a single center and are, therefore, limited in their generalizability.

5. Conclusions

Overall, this study represents a large cross-sectional analysis of PN patients’ to-date, in which an association with peripheral neuropathies is observed. This association with peripheral neuropathies may suggest the importance of neuropathic changes in the pathogenesis of PN. In addition, PN demonstrates distinct differences in comparison to AD and psoriasis, despite their roles as chronic inflammatory pruritic conditions. Clinically, our study underscores an important link between PN and peripheral neuropathies. This may highlight an increased propensity for neural dysregulation in patients with PN. As such, consideration and evaluation of peripheral neuropathies should be considered in patients with PN.

Author Contributions

The authors of this manuscript contributed in the following manner: J.-D.M.H., methodology, data curation, formal analysis, original draft preparation, writing, review, editing, and funding acquisition. T.E.W., original draft preparation and editing. M.B., data curation and visualization. R.K., visualization. K.A.W., Project administration. S.H., original draft preparation. M.M.K., editing and review. S.G.K., conceptualization, editing, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canadian Dermatology Foundation through the Frederick Kalz Bursary.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kwon C.D., Khanna R., Williams K.A., Kwatra M.M., Kwatra S.G. Diagnostic Workup and Evaluation of Patients with Prurigo Nodularis. Medicines. 2019;6:97. doi: 10.3390/medicines6040097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang A.H., Canner J.K., Khanna R., Kang S., Kwatra S.G. Real-world prevalence of prurigo nodularis and burden of associated diseases. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.07.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Székely H., Pónyai G., Temesvári E., Berczi L., Hársing J., Kárpáti S., Herszényi L., Tulassay Z., Juhasz M. Association of collagenous colitis with prurigo nodularis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009;21:946–951. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328321b0e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Payne R., Wilkinson J.D., Mckee P.H., Jurecka W., Black M.M. Nodular prurigo—A clinicopathological study of 46 patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 1985;113:431–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dazzi C., Erma D., Piccinno R., Veraldi S., Caccialanza M. Psychological factors involved in prurigo nodularis: A pilot study. J. Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:211–214. doi: 10.3109/09546631003674321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bobko S., Zeidler C., Osada N., Riepe C., Pfleiderer B., Pogatzki-Zahn E., Lvov A., Ständer S. Intraepidermal Nerve Fibre Density is Decreased in Lesional and Inter-lesional Prurigo Nodularis and Reconstitutes on Healing of Lesions. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2016;96:404–406. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuhknecht B., Marziniak M., Wissel A., Phan N., Pappai D., Dangelmaier J., Metze D., Ständer S. Reduced intraepidermal nerve fibre density in lesional and nonlesional prurigo nodularis skin as a potential sign of subclinical cutaneous neuropathy. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011;165:85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaalasti A., Suomalainen H., Rechardt L. Calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactivity in prurigo nodularis: A comparative study with neurodermatitis circumscripta. Br. J. Dermatol. 1989;120:619–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira M.P., Pogatzki-Zahn E., Snels C., Vu T.H., Üçeyler N., Loser K., Sommer C., Evers A.W.M., Van Laarhoven A.I.M., Agelopoulos K., et al. There is no functional small-fibre neuropathy in prurigo nodularis despite neuroanatomical alterations. Exp. Dermatol. 2017;26:969–971. doi: 10.1111/exd.13343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bharati A., Wilson N.J.E. Peripheral neuropathy associated with nodular prurigo. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2017;26:969–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazza M., Guerriero G., Marano G., Janiri L., Bria P., Mazza S. Treatment of prurigo nodularis with pregabalin. J. Clin. Pharm Ther. 2013;38:16–18. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang A.H., Canner J.K., Kang S., Kwatra S.G. Analysis of real-world treatment patterns in patients with prurigo nodularis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019;82:34–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aguh C., Kwatra S.G., He A., Okoye G.A. Thalidomide for the Treatment of Chronic Refractory Prurigo Nodularis. Dermatol. Online J. 2018;24:1–6. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800214-8.00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma D., Kwatra S.G. Thalidomide for the treatment of chronic refractory pruritus. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016;74:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarikci N., Kocatürk E., Güngör Ş., Topal I.O., Can P.Ü., Singer R. Pruritus in Systemic Diseases: A Review of Etiological Factors and New Treatment Modalities. Sci. World J. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/803752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jørgensen K.M., Egeberg A., Gislason G.H., Skov L., Thyssen J.P. Anxiety, depression and suicide in patients with prurigo nodularis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017;31:e106–e107. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boozalis E., Tang O., Patel S., Semenov Y.R., Pereira M.P., Stander S., Kang S., Kwatra S.G. Ethnic differences and comorbidities of 909 prurigo nodularis patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018;79:714–719.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews S.N., Cockerell C.J. Prurigo nodularis in, H.I.V-infected individuals. Int J. Dermatol. 1998;37:401–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reich A., Ständer S., Szepietowski J.C. Drug-induced pruritus: A review. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2009;89:236–244. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tierney E.F., Thurman D.J., Beckles G.L., Cadwell B.L. Association of statin use with peripheral neuropathy in the, U.S. population 40 years of age or older. J. Diabetes. 2012;5:207–215. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldinger T.P., Siegle R.J., Weber W., Voorhees J.J. Dapsone-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Arch. Dermatol. 1984;120:356–359. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1984.01650390078016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goolsby T.A., Jakeman B., Gaynes R.P. Clinical relevance of metronidazole and peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review of the literature. Int J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2018;51:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spring P., Gschwind I., Gilliet M. Prurigo nodularis: Retrospective study of 13 cases managed with methotrexate. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2014;39:468–473. doi: 10.1111/ced.12365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider G., Hockmann J., Ständer S., Luger T.A., Heuft G. Psychological factors in prurigo nodularis in comparison with psoriasis vulgaris: Results of a case-control study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006;154:61–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinke S., Zeidler C., Riepe C., Bruland P., Soto-Rey I., Storck M., Augustin M., Bobko S., Garcovich S., Legat F.J., et al. Humanistic burden of chronic pruritus in patients with inflammatory dermatoses: Results of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Network on Assessment of Severity and Burden of Pruritus (PruNet) cross-sectional trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018;79:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iking A., Grundmann S., Chatzigeorgakidis E., Phan N.Q., Klein D., Ständer S. Prurigo as a symptom of atopic and non-atopic diseases: Aetiological survey in a consecutive cohort of 108 patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2013;27:550–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baykal C., Ozkaya-Bayazit E., Gökdemir G., Diz Küçükkaya R. The combined occurrence of macular amyloidosis and prurigo nodularis. [(accessed on 22 October 2018)];Eur. J. Dermatol. 2000 10:297–299. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10846258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larson V.A., Tang O., Stander S., Miller L.S., Kang S., Kwatra S.G. Association between prurigo nodularis and malignancy in middle-aged adults. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019;81:1198–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]