Abstract

Of the eight clinically defined neuropathies associated with HIV infection, there is compelling evidence that acute and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (IDPN) have an autoimmune pathogenesis. Many non‐HIV infected individuals who suffer from sensorymotor nerve dysfunction have autoimmune indicators. The immunopathogenesis of demyelination must involve neuritogenic components in myelin. The various antigens suspected to play a role in HIV‐seronegative IDPN include (i) P2 protein; (ii) sulfatide (GalS); (iii) various gangliosides (especially GM1); (iv) galactocerebroside (GalC); and (v) glycoproteins or glycolipids with the carbohydrate epitope glucuronyl‐3‐sulfate. These glycoproteins or glycolipids may be individually targeted, or an immune attack may be raised against a combination of any of these epitopes. The glycolipids, however, especially GalS, have recently evoked much interest as mediators of immune events underlying both non‐HIV and HIV‐associated demyelinating neuropathies. The present review outlines the recent research findings of antiglycolipid antibodies present in HIV‐infected patients with and without peripheral nerve dysfunction, in an attempt to arrive at some consensus as to whether these antibodies may play a role in the immunopathogenesis of HIV‐associated inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.

Keywords: antibodies, galactocerebroside, gangliosides, human immunodeficiency virus, inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, sulfatide

INTRODUCTION

During the course of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection at least 20% of infected individuals develop overt peripheral nerve disorders. 1 , 2 , 3 A further 13–35% have been suggested to have an underlying subclinical neuropathy detectable only by nerve conduction studies. 4 , 5 This review details investigations aimed at determining the antigenicity of peripheral myelin lipids in inflammatory demyelinating disorders associated with HIV infection.

Eight different forms of HIV‐associated neuropathy have been described: 6 (i) distal predominantly sensory neuropathy (DPSN); (ii) vasculitic neuropathy; (iii) lymphomatous neuropathy; (iv) cytomegalovirus (CMV); lumbosacral polyradiculopathy; (v) Varicella zoster virus (VZV) polyradiculopathy; (vi) acute and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (IDPN); (vii) autonomic neuropathy; and (viii) neuropathy induced by di‐deoxy‐inosine (ddI) and di‐deoxy‐cytidine (ddC) therapy. Other minor forms of neuropathy associated with HIV infection have been documented. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11

DPSN is the commonest neuropathy and it occurs in up to 35% of individuals with advanced HIV infection. 3 , 6 Although the pathology of DPSN has been determined as retrograde distal axonal degeneration (‘dying back’ axonopathy) and drop out of dorsal root ganglion neurons, 12 , 13 little is known of its pathogenesis. In contrast, two other types of HIV‐associated neuropathies, inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (IDPN) (in both acute (AIDPN) and chronic (CIDPN) forms), and vasculitic neuropathy have clinical and pathological features that suggest an autoimmune pathogenesis. Both occur during phases of HIV infection in which T lymphocytes are not significantly depleted so that sensitization of T cells to peripheral nerve antigens can occur. Circulating antibodies of IgG and IgM isotypes against myelin have been found in the serum of HIV‐seropositive individuals with IDPN and vasculitic neuropathy, and symptomatic improvement after plasmapheresis has been recorded in both groups. 14 To date only a small number of individuals with HIV infection and symptoms of neuropathy has been studied. There are no data regarding the prevalence of antibodies against peripheral myelin and axonal epitopes in HIV‐infected individuals without overt neuropathic symptoms. Antiprotein and antiglycolipid reactivity, however, has been demonstrated in various neuropathic syndromes (especially Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS)) in individuals without HIV infection. Such data may assist in reaching a consensus on the significance of antimyelin antibodies in the pathogenesis of HIV‐associated neuropathy.

HIV‐ASSOCIATED INFLAMMATORY DEMYELINATING POLYNEUROPATHY

HIV‐infected patients with AIDPN develop clinical symptoms which are similar to HIV‐seronegative GBS. 15 , 16 In addition to the presence of antibodies against HIV, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleiocytosis is the most clearly distinguishing feature of HIV‐associated AIDPN. 15 This, however, is not specific for AIDPN because HIV‐infected patients (with or without AIDPN) have up to 50 mononuclear leukocytes per mm 3 in the CSF, whereas GBS patients rarely have more then 10 mononuclear leukocytes per mm 3 . 17 The fact that CIDPN exhibits some clinical similarities with AIDPN and that they both respond favorably to plasmapheresis therapy is an indication that there is a common etiology. 15

The predominant feature of HIV‐associated AIDPN is primary demyelination. A small proportion of patients has axonal degeneration which is sometimes the predominant feature. 15 , 18 Microscopic examination of nerve biopsies reveals moderate subperineurial edema reflecting breakdown of the blood–nerve barrier (BNB), small numbers of lymphocytes near endoneurial vessels and within the endoneurial space, and demyelinated and remyelinating fibers. There is usually prominent infiltration by macrophages containing myelin. More severely involved nerves display frequent fibers undergoing demyelination, often with macrophage‐mediated myelin stripping. Extensive endoneurial mononuclear cell infiltrates and perivascular cuffs of inflammatory cells in the epineurium can also be seen. 15 , 19 The CD4:CD8 ratio in the nerve has also been shown to reflect that of the peripheral blood, suggesting that many cells may enter the peripheral nerve lesions non‐specifically secondary to a breakdown of the BNB. 15 , 20 , 21

Because this disorder generally occurs in HIV‐infected individuals with a CD4 count > 500/μL or at the stage of seroconversion, and there is an underlying pathology of primary demyelination with active infiltration of immunocompetent leukocytes similar to its non‐HIV counterpart, this disorder has been suggested to be immune mediated. 15 Further evidence comes from data showing high titers of circulating antiperipheral nerve myelin antibodies elevated acutely and decreased during convalescence, 22 , 23 and perineurial IgM deposits in HIV‐infected patients with neuropathy. 14 The strongest argument for this hypothesis is favorable patient responses to plasmapheresis, corticosteroid and intravenous immunoglobulin treatment. 24 , 25

ANTIBODIES AGAINST MYELIN CONSTITUENTS

Antibodies that react with myelin constituents have been frequently demonstrated in the circulation of patients with a variety of demyelinating neuropathies and other neurological conditions, in particular AIDPN, CIDPN and polyneuropathy associated with monoclonal IgM paraproteinemia. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 Clinical improvement in some AIDPN patients, and declining serum titers of antimyelin antibodies after plasmapheresis, suggest that the pathogenesis, at least in part, is likely to involve disordered humoral immunity. 15 , 37 , 38 , 39

Many investigators have reported immunoreactivity against various glycolipids of peripheral nervous system myelin in patients with IDPN. 34 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 This immunoreactivity has implicated these glycolipids in the pathogenesis of immune demyelinating polyneuropathies and some motor neuropathies, in particular multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN). 42 , 43 , 44

Complex carbohydrates which are constituents of peripheral nerve myelin contain repetitive hexose units. These can directly activate B cells by cross‐linking surface immunoglobulin receptors in an antigen‐specific manner. This may augment a non‐specific T‐cell response. 45 These complex carbohydrates are also capable of eliciting a polyclonal B‐cell response with the generation of specific IgM antibodies.

For an IgG response to occur, the antigen must be processed by an antigen‐presenting cell and presented to T cells via the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II. 46 , 47 Glycolipid molecules such as gangliosides cannot be processed intracellularly and presented to the immune system in this manner. 48 For these glycolipids to be neuritogenic they need either to be closely associated with a protein or contain an epitope that cross‐reacts with a glycoprotein, unless they are T‐cell‐independent antigens. 45 , 49 CD5‐expressing B cells react with carbohydrates and may be able to process and present a peptide fragment thereby eliciting T‐cell help. 50 , 51 , 52 This process could then lead to the generation of IgG antibodies against glycolipid carbohydrate moieties.

There exists, however, a subpopulation of T cells bearing the αβ T‐cell receptor (TCR) that recognizes non‐peptidic components of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. 53 These T cells are specific for lipids and glycolipids from the mycobacterium cell wall, recognizing the carbohydrate moiety of the glycolipid. More importantly, these T cells recognize glycolipids by a non‐MHC‐type mechanism, involving the CD1b molecule which can present glycolipid to the T‐cell receptor. 54 Of major significance were the recent findings of Khalili‐Shirazi et al., who demonstrated strong labeling of CD1b on endoneurial macrophages and on myelinated nerve fibers in AIDPN biopsied nerves but could not see such patterns in other diseased (various peripheral neuropathies) and normal nerves, suggesting a strong association between the upregulation of CD1 and inflammatory neuropathy. 55 Further evidence for this association were the recent results presented by Shamshiev et al. who showed that circulating T cells isolated from multiple sclerosis (MS) patients with either active or stable demyelinating lesions were reactive against various glycolipids with different clones showing intense reactivity with gangliosides, GalC and GalS. 56 Importantly, one specific CD1b‐restricted T‐cell clone, reacting against the monosialoganglioside GM1, was shown to be specifically recognized by the TCR and is able to discriminate between small variations in the carbohydrate moieties. These investigators went further to show that the glycolipid reactive T cells more often show a T helper (Th)1‐like functional phenotype because they release the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α and interferon (IFN)‐γ. These findings would suggest that in MS there is an expansion of glycolipid‐reactive T cells and that these may be reponsible for the onset and progression of inflammatory demyelinating lesions seen in this disease. It is possible that B cells generating specific antiglycolipid antibodies may be activated by these CD1b‐positive, glycolipid‐reactive T cells.

IgM paraproteinemic neuropathy was one of the first disorders to implicate antiglycolipid antibodies in the pathogenesis of a peripheral demyelinating disorder. 57 , 58 It was found that the myelin‐associated glycoprotein (MAG) carbohydrate moiety of peripheral myelin is also present on the acidic peripheral myelin glycolipid sulfoglucoronyl paragloboside (SGPG). 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 Antibodies to SGPG have since been shown to cause demyelination and other pathological changes such as widening of myelin lamellae in rats, when injected intraneurally 63 , 64 or by systemic passive transfer of immune serum into chickens. 65 The sulfoglucoronyl moiety or a similar carbohydrate residue has been shown to be essential for antibody binding. This carbohydrate moiety is shared by several other nervous system glycoconjugates besides MAG and P0, including the adhesion molecules J1 and neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and several 20–26‐kDa peripheral nervous system (PNS) glycoproteins. 42 It is possible that the pathological findings seen in patients with these circulating autoantibodies might arise from interference with the structural integrity of PNS myelin. Also, these antibodies may disrupt critically important interactions between the PNS neurons and the accompanying Schwann cells by binding to cell adhesion molecules. 42 These antibodies have never been demonstrated in HIV‐infected patients with neuropathy.

ANTI‐GALS ANTIBODIES

Anti‐sulfated carbohydrate antibodies have been detected frequently in patients with distal sensory polyneuropathies without HIV infection. These antibodies are present to a lesser degree in proximal polyneuropathies and very little reactivity is seen in patients with sensory ganglionopathy. 66 Patients with anti‐GalS reactivity exhibit predominantly sensory neuropathic symptoms. There has been much speculation surrounding the involvement of anti‐GalS antibodies in sensory neuropathies. Quattrini et al. screened 200 plasma samples from patients with various peripheral neuropathies and other neurological and immunological diseases. 67 Five of these samples contained a high anti‐GalS antibody titer. All five samples were from patients with sensory impairment, one patient also suffering from MS. Pre‐absorption with GalS and not GalC eliminated the tissue‐binding activity of these antibodies. The specificity of the anti‐GalS antibodies is largely directed at the sulfate (SO3) and hydroxy (OH) groups of the sugar residue. 68 Antibodies against GalS were also found to bind only to fixed sections of peripheral and central myelin. 67 This tends to suggest that the GalS epitope is shielded normally but may be exposed in some types of nerve injury and during tissue fixation.

Anti‐GalS IgM antibodies are restricted to the lambda (λ) subclass; this restriction may result from preferential utilization of particular immunoglobulin variable‐region genes by these antibodies 67 similar to that reported for antibodies with anti‐DNA, rheumatoid factor, cold agglutinin or anti‐MAG reactivity. 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 It has been suggested that low levels of anti‐GalS antibodies may be common constituents of the normal human immune repertoire and may be secreted by the CD5‐positive subset of B cells, similar to other naturally occurring anticarbohydrate IgM antibodies. 73 These B cells might be activated by GalS incorporated into the envelope of a budding virus, 74 by cross‐reactive foreign antigens or antigen complexes, and may be excessively produced by expanded B cell clones in monoclonal gammopathies.

Further evidence that these antibodies cause sensory symptoms comes from studies of the relative permeability of the BNB in dorsal root ganglia (DRG). 75 This exposes DRG neurons as potential targets of anti‐GalS antibodies. Anti‐GalS antibodies have been shown to bind to the surface of unfixed rat DRG neurons. 67 The high content of GalS 67 and the BNB permeability in DRG support the theory that these antibodies may contribute to sensory syndromes. It is possible that the antibodies could also disrupt the interaction of GalS with extracellular adhesion molecules. This would, in turn, cause disruption of the close contact between axons and Schwann cells that is necessary to maintain the integrity of myelinated axons. 76 Anti‐GalS antibodies could also interfere with the function of associated β‐endorphin receptors, 77 or damage cells through complement fixation.

Anti‐GalS antibodies are frequently found in patients with IDPN. 41 , 42 As has been already described, GalS appears to be concentrated on the external surface of the myelin sheath. 78 This would suggest that anti‐GalS autoantibodies could play a role in the pathogenesis of motor neuropathies such as GBS. Anti‐GalS antibodies have been detected in 65% of patients with GBS and also in 87% of patients with CIDPN; but these antibodies are found in only 15% of control sera. 41

Another study has shown a direct relationship between anti‐GalS antibodies and the process of immune demyelination in the PNS. 79 Passive transfer of purified monoclonal anti‐GalS IgM antibodies from a patient with benign IgM‐λ paraproteinemic demyelinating polyneuropathy to newborn rabbits produced demyelinating nerve lesions similar to those seen in the donor. The experimental lesions showed direct binding of anti‐GalS antibodies to Schmidt–Lanterman incisures and nodes of Ranvier. These antibodies were also shown to bind to satellite cells in DRG, suggesting a possible pathogenetic role of anti‐GalS antibodies in sensorimotor syndromes.

Anti‐GalS antibodies have been demonstrated in the serum and CSF of HIV‐infected patients with neurological involvement, particularly those patients with peripheral nerve dysfunction. 80 These investigators found that six of the seven CSF samples obtained from HIV‐associated peripheral neuropathy patients contained IgG anti‐GalS antibodies. They concluded that anti‐GalS antibodies present within the CSF of these patients could be synthesized intrathecally by infiltrating peripheral blood plasma cells. These could also enter peripheral nerves through an altered BNB. Alternatively, these antibodies may bind to DRG tissue components after passing through the permeable DRG‐BNB.

Recently Gisslen et al. described anti‐GalS IgG antibodies present in HIV‐infected individuals both with and without neurological involvement. 81 These investigators studied 25 patients who were HIV seropositive, of which nine had documented neuropsychiatric symptoms (three with AIDS dementia complex; two with cerebral toxoplasmosis; two with progressive multifocal leuko‐encephalopathy; one with vacuolar myelopathy; one with new‐onset psychosis). Twenty‐four of the 25 HIV‐infected patients had GalS antibody titers ranging from 1 : 3200 to 1 : 25 600. No antibodies were found in the CSF but the majority of patients had signs of intrathecal immunoglobulin production, with 12/25 showing an increased IgG index and 22/25 showing two or more oligoclonal bands enriched in CSF. Gisslen et al. concluded that anti‐GalS antibodies did not seem to be involved in the pathogenesis of central nervous system (CNS) myelin damage in HIV‐1 infection. 81 But they did discuss the possibility that these antibodies may induce immune demyelination preferentially in the PNS if there exists a difference in the struc‐tural location of GalS in central and peripheral myelin membranes.

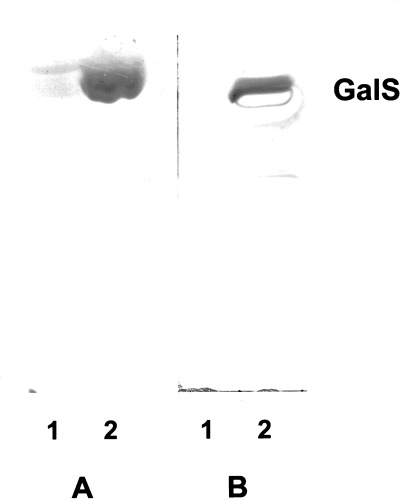

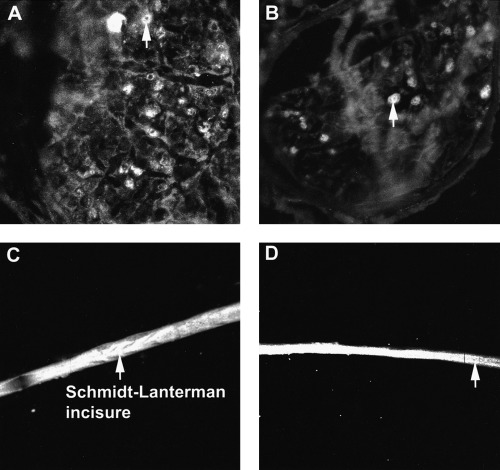

We have previously shown peripheral nerve immunoreactivity by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in a cohort of HIV‐positive plasma samples. 82 Eighteen of the 35 plasma samples screened contained antiperipheral nerve myelin (PNM) IgM antibodies and 11 had IgG anti‐PNM antibodies. Thin layer chromatography (TLC)‐immunostaining and western immunoblotting determined reactivity to be purely against glycolipid components of PNM. The majority of IgM and IgG antibody reactivity was found to be directed against GalS (Fig. 1). Of the 35 HIV‐positive samples screened by ELISA, five were considered to have raised anti‐GalS IgM antibody titers (i.e. > 1000 arbitrary units (AU)/L) and six samples had raised anti‐GalS IgG antibody titers (> 1000 AU/L; 1, 2). 83 The reactivity of these antibodies, which was directed specifically against GalS, was localized by indirect immunofluorescence to myelin (Fig. 2a,b). In teased nerve fiber preparations it was clear that although staining of myelin was diffuse, staining at the paranodal regions and Schmidt–Lanterman incisures was more intense (Fig. 2c,d). 84

Figure 1.

Thin layer chromatography immunostaining procedure detecting both IgM and IgG anti‐GalS antibody reactivity in plasma from HIV‐infected individuals. Each lane was loaded with 5 μg of either neutral (lane 1) or acidic (lane 2) glycolipids extracted from human sciatic nerve myelin. IgG anti‐GalS reactivity (a) and IgM anti‐GalS reactivity (b) both from different HIV‐infected individuals.

Table 1.

Correlation of IgM anti‐GalS titer in HIV patient plasma with CD4 lymphocyte count

| Titer (AU/L) | Total no. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 count | 200 | 500 | 1000 | 2000 | reacting |

| > 500 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| 200–500 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| < 200 | – | 1 | 1 | – | 2 |

| Total | 6 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 19 |

AU, arbitrary units.

Table 2.

Correlation of IgG anti‐GalS titer in HIV patient plasma with CD4 lymphocyte count

| Titer (AU/L) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 count (/μL of peripheral blood) | 200 | 500 | 2000 | 5000 | 10 000 | Total no. reacting |

| > 500 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 200–500 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| < 200 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Total | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

AU, arbitrary units.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence of unfixed human sciatic nerve sections and fixed teased nerve fibers. IgM anti‐GalS antibody reactivity from plasma obtained from an HIV‐infected individual (a); IgG anti‐GalS antibody reactivity from plasma obtained from a different HIV‐infected individual (b). IgM anti‐GalS antibody reactivity from plasma obtained from an HIV‐infected individual (c); IgG anti‐GalS antibody reactivity from plasma obtained from a different HIV‐ infected individual (d). Arrows show myelin staining.

These anti‐GalS antibodies were present in HIV‐infected individuals with and without immunosuppression. 82 This suggests that in immunosuppressed HIV‐positive individuals (CD4 lymphocyte counts < 200/μL of peripheral blood), CD5‐positive B cells may be responsible for producing autoantibodies against the carbohydrate moieties of peripheral myelin glycolipids because high‐titer antibodies were present in these patients. Alternatively, these antibodies may be generated during hypergam‐maglobulinemia 85 because polyclonal generation of immunoglobulins is common in HIV infection even when immunosuppression is severe. 85 , 86 A significant association between the presence of autoantibodies in HIV‐infected patients and the depletion of CD4 lymphocyte counts has been documented. 87 Massabki et al., however, found that patients with low‐titer autoantibodies do not develop autoimmune disease. 87 In contrast, our findings indicate that certain antiglycolipid antibodies (specifically IgG anti‐GalS) can be present in very high titers.

In the present study, titers of IgG anti‐GalS antibodies in HIV‐infected patients were as high as 10 000 AU/L compared with IgM anti‐GalS antibody titers of up to 2000 AU/L. The higher IgG titers may reflect recurrent episodes of subclinical damage to myelin. A similar profile was found in two HIV‐negative patients with demyelinating neuropathy associated with IgM paraproteinemia. In these, the anti‐GalS IgM antibody titers detected were 10 000 and 1 000 000 AU/L, respectively. 35 But antibody titers in plasma samples from HIV‐infected patients with neuropathy were moderate and could not be regarded as raised. The highest anti‐GalS IgG and IgM antibody titers in these patients were 1000 and 500 AU/L, respectively. 83

Experimental polyneuropathy has been produced by Qin and Guan in guinea‐pigs using GalS as the neuritogen. 88 These investigators correlated IgG antibody titer levels with the pathological findings in nerves of 13 animals injected with bovine brain GalS. All but two animals were symptomatic. These two had only moderately raised titers (1 : 800, 1 : 1600). The 11 symptomatic animals showed typical GBS and the intensity of their motor deficits correlated significantly with their serum antibody titers. Demyelination (especially in nerve rootlets) was the major pathology observed. Deposits of IgG were found at nodes of Ranvier and in myelin sheaths. The Neuropathology Research Laboratory at Royal Melbourne Hospital has been able to show that HIV‐positive plasma samples with raised IgM or IgG anti‐GalS antibody titers showed strong binding to myelin but no binding to the axonal membrane. 84 It is possible that raised anti‐GalS antibodies may predict a higher likelihood of neuropathic disease in HIV‐infected patients.

ANTIGANGLIOSIDE ANTIBODIES

Antibodies against gangliosides have been found in a variety of human neurological disorders of both immune and non‐immune pathogenesis, 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 but their contribution to inflammatory demyelination is questioned. 93 Despite inconsistent data linking various antiganglioside antibodies to certain neuropathies and neurodegenerative conditions, two neuropathies stand out with regard to their association with specific antiganglioside autoantibodies.

Patients with multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN) commonly have anti‐GM1 antibodies present in high titers. 44 , 94 One study reported anti‐GM1 IgG and IgM antibodies in 90% of patients with MMN. 94 Among these, 60% of patients had high titers. Another study reported an ability to stimulate the production of anti‐GM1 antibodies from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNC) isolated from MMN patients. 95 Because GM1 is concentrated at the nodes of Ranvier, 44 it remains plausible that these antibodies may cause both electrophysiological abnormalities such as conduction block and pathological abnormalities, in particular paranodal demyelination. Injection of serum containing high titers of anti‐GM1 antibodies from a MMN patient into rat sciatic nerve resulted in conduction block with temporal dispersion, demyelination in 6.5% of the fibers and immunoglobulin deposition at the nodes of Ranvier. 44

The other disorder showing antiganglioside reactivity is the Miller–Fisher syndrome. This syndrome is strongly associated with anti‐GQ1b IgG antibodies. 96 , 97 , 98 GQ1b ganglioside is largely concentrated in the oculomotor, trochlear and abducens nerves in paranodal regions. 96 , 97 , 98 Most patients have a favorable response to plasma exchange.

Apart from these two disorders, there has been conflicting evidence regarding the role of gangliosides as possible antigens in GBS. In a study by Ilyas et al. five of 26 patients with GBS had high titers of antibodies to gangliosides. 99 One of these patients had strong IgG reactivity against the most predominant ganglioside of PNS myelin, LM1. No antiganglioside antibodies were found in sera of healthy controls. Alternatively, Svennerholm and Fredman found antiganglioside reactivity in 39 of 50 patients with GBS, but also in 47 of 197 normal control individuals. 100

Significant levels of antibodies against asialo‐GM1 neutral ganglioside have been reported in 36% of 31 homosexual men with AIDS. 101 Whether these antibodies participate in the pathogenesis of any of the various peripheral neuropathies seen in patients infected with HIV remains to be determined. Sorice et al. detected both IgG and IgM antiganglioside antibodies in the CSF in three AIDS patients with progressive encephalopathy and signs of hypomyelination. 102 Two of the samples were shown to react specifically with GM3, GM1, and GD1a, and one with GD1a alone. None of the sera from HIV‐positive patients without encephalopathy contained antiganglioside reactivity, nor did any of the HIV‐seronegative control samples with and without CNS disease. Whether these patients had concomitant peripheral nerve demyelination is not known, but these data demonstrate that antiganglioside antibodies can be present in patients with advanced HIV infection.

We have shown that antiganglioside antibody titers in HIV‐positive plasma samples do not appear to have any clinical significance. Only one sample contained a relatively raised titer of 2000 AU/L and only seven of the 35 HIV‐positive plasma samples showed some reactivity against the various gangliosides, and so it is reasonable to conclude that these glycolipids are not candidate autoantigens in HIV‐infected individuals (Table 3; Petratos et al. unpubl. data, 1998). Data linking antiganglioside antibodies to peripheral neuropathy have demonstrated these antibodies only in patients with motor deficits. The most predominant neuropathy in HIV infection, however, is DPSN, a sensory disorder. 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 This may explain the absence of antiganglioside antibodies in the HIV‐positive plasma samples tested in the present study.

Table 3.

Correlation of IgG anti‐ganglioside titer in HIV patient plasma with CD4 lymphocyte count

| Titer (AU/L) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 count | 100 | 200 | 500 | 2000 | Total no. reacting |

| > 500 | – | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| 200–500 | – | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| < 200 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Total | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

AU, arbitrary units.

ANTI‐GALC ANTIBODIES

There have been few data published regarding a possible role for GalC and other minor glycolipids in the pathogenesis of immune demyelinating neuropathies. Furthermore, no such data have been published for HIV‐infected individuals with and without peripheral neuropathy. There has been wide documentation of anti‐GalC antibody‐induced experimental allergic neuritis (EAN), which closely depicts the pathology of IDPN. The only difference from IDPN is that this type of EAN does not show T lymphocyte infiltration of affected nerves. 107 Considering that GalC is the most predominant glycolipid in PNS myelin, 108 , 109 , 110 it is possible that the presence of anti‐GalC antibodies may be an early indication of a propensity for demyelination. Investigators have searched for anti‐GalC antibodies in plasma samples from GBS patients but have not been able to detect elevated antibody levels relative to healthy donor samples. 42 The only group that found some antibody activity was able to detect IgM reactivity against GalC in only two samples obtained from 52 acute GBS sera. 8 These data would suggest that anti‐GalC anti‐bodies are not elevated in human immune demyelinating neuropathies. 111 , 112

We have shown only three of 35 HIV‐positive plasma samples screened by ELISA to have relatively raised antibody titers of 2000 AU/L (Table 4; Petratos et al. unpubl. data, 1998). Of interest, these were from patients with CD4 lymphocyte counts < 200/μL and the antibody class was IgG. This pattern was similar to that seen with the anti‐GalS IgG titers described earlier. A similar pathway augmenting anti‐GalC IgG antibodies could have been operating in these three HIV‐infected individuals.

Table 4.

Correlation of IgG anti‐GalC titer in HIV patient plasma with CD4 lymphocyte count

| Titer (AU/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 count | 500 | 2000 | Total no. reacting |

| > 500 | – | – | 0 |

| 200–500 | 1 | 1 | |

| < 200 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Total | 3 | 3 | 6 |

AU, arbitrary units.

Other neutral glycolipids have been proposed as neuritogens involved in immune demyelinating disorders. Koski et al. reported the presence of antineutral glycolipid antibodies in all of the 10 GBS patients studied whereas none of the control group contained these antibodies. 113 Five GBS sera showed reactivity against a minor neutral lipid migrating between paragloboside and neolactohexaosesyl ceramide. Ilyas et al. demonstrated intense reactivity in a proportion of sera obtained from GBS patients against purified Forssman glycolipid and a number of glycolipids in higher neutral glycolipid‐enriched fractions of human cauda equina and dog sciatic nerve. 42 But similar results were found in the control group. These results contrast with the findings of Koski et al., who demonstrated high IgM antibody titers against Forssman neutral glycolipid in GBS sera but could not find the same reactivity in their control group. 28

The majority of these glycolipids are not exclusively found in the PNS. Glycolipids such as the gangliosides, GalC and GalS are major components of central myelin. 114 Hence, the question arises as to why IDPN is localized to the PNS without concomitant CNS dysfunction. Studies have shown, however, that some patients with CNS demyelination may have concomitant PNS demyelination. 115 , 116 Kinoshita et al. showed at autopsy that a patient who had died from acute disseminated encephalomyelitis also had inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculitis. 116 This raises the question of a shared immunological epitope between the CNS and the PNS. There have been other reports of this type of finding in CNS disorders. 115 , 117 , 118 Adding to the body of evidence supporting this shared epitope hypothesis is the finding of active peripheral demyelinating lesions in MS patients. 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 In HIV infection both CNS and PNS compartments may be infected, leading to concomitant lesions. 124

THE AUTOIMMUNE HYPOTHESIS

In the early stages of HIV infection, autoimmune diseases such as immune thrombocytopenia and vasculitis can complicate the disease. 125 These autoantibodies are usually produced as part of the immune dysregulation induced by HIV infection. 85 , 86 Neurological disorders such as those seen for T cell depletion during HIV infection 126 may be in part due to neuroimmunological responses to HIV infection. 127 Dysregulation of the immune system may play a role in HIV‐associated neuropathies. Immunological phenomena such as antilymphocyte antibodies, circulating immune complexes, cross‐reacting antigens to myelin, and abnormally expressed human leukocyte antigens (HLA) may play significant roles in determining neurological outcomes in HIV‐infected patients. 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 Also, during immunosuppression in HIV‐infected individuals, depletion of Th cells may impair the generation of suppressor cells, allowing a cell‐mediated autoimmune response similar to that seen in the P2‐specific EAN model. 131 HIV‐associated IDPN has the same clinical and pathological features as in non‐HIV‐associated GBS and the experimental animal model, EAN. 15 The inflammatory lesions are frequently associated with foci of demyelination or tissue necrosis, similar to those seen in sheep infected with another of the lentiviruses, visna. 132 It is also possible that mononeuropathy multiplex may be of autoimmune pathogenesis because similar lesions may occur in immune complex‐mediated vasculitis involving peripheral nerves. 133

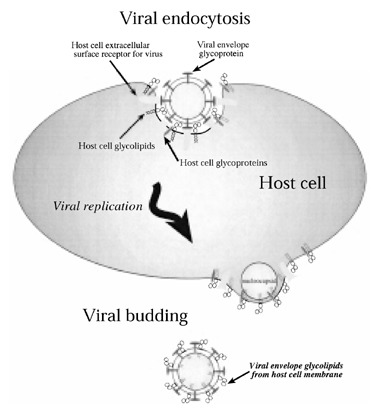

Alternatively, antibodies reacting against peripheral nerve constituents could possibly be generated from the productive infection of cells outside the peripheral nerve compartment. Direct HIV infection of cells containing epitopes (such as glycolipids) similar to those expressed in the PNS may provoke an autoimmune response: (i) by altering the structural integrity of cell membrane components; or (ii) by the incorporation of host cell glycolipid into the viral coat (viral budding), allowing them to become antigenic. 134 Enveloped budding viruses (such as HIV) take host cell glycolipid into their coat (Fig. 3). Glycolipid presented in the virus coat to the immune system may be much more antigenic than glycolipid alone. HIV has been reported to infect cells containing cell membrane glycolipids, similar to those found in Schwann cells, myelin, 135 peripheral T cells, 136 in vitro differentiated monocyte‐derived macrophages 137 and epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal system. 138 , 139 It is therefore plausible to suggest that these glycolipids, incorporated into the membrane of budding virus and presented to the immune system, can provoke both cell‐mediated and humoral antibody attacks against glycolipid present on PNS cells, Schwann cells and myelin.

Figure 3.

Proposed incorporation of host cell glycolipid into budding viral particles. As the HIV replicates and subsequently buds off from a host cell membrane enriched in glycolipid, it incorporates these glycolipids into its glycoprotein coat. Upon presentation to the host immune system the glycolipid carbohydrate epitopes are recognized as ‘foreign’ and a primary immune response is elicited.

Evidence for this pathogenic mechanism has been clearly demonstrated for other viruses. Almeida and Waterson have shown that only the viral protein spikes of corona virus derived from chicken fibroblasts can be labeled by immune serum. 140 But when the coronavirus derived from chickens is used to make immune serum in rabbits, both the viral protein spikes and the intermediate membrane envelope of the virus are labeled, indicating that the chicken‐derived virus is able to produce considerable antichicken host‐membrane antibody in the rabbit. An example more pertinent to HIV is that of Friend leukemia virus (a retrovirus). This virus buds from the erythrocyte membrane, taking antigen into its coat, 141 and can evoke an immune reaction that causes hemolysis of normal, uninfected erythrocytes. 142

Of interest is the finding that mice inoculated with the neurotropic strain of vaccinia virus produce antibodies that bind to normal, uninfected myelin and oligodendrocytes, indicating that the virus presents antigenic myelin and oligodendrocyte membrane components to the immune system. 143 This does not, however, occur when the dermatotropic strain of virus is used. A possible cellular immune destruction of neural tissue was demonstrated by Rook and Webb, who showed that cytotoxic T cells sensitized to tick‐borne encephalitis (TBE) virus killed not only TBE‐infected glial cells but also a significant percentage of normal, uninfected glial cells. 144

Experiments have shown that the lipid composition of the envelope of paramyxovirus SV5, cultured in four different host cells with different lipid compositions, very closely resembles the membrane of the host cell in which it was cultured. 145 The lipid composition of the viral envelope has been shown to resemble closely those of the host cells from which they are derived in mumps, 146 influenza, 147 , 148 Sinbis, 149 , 150 Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis, 151 and Semliki Forest viruses (SFV). 152 , 153 , 154 The SFV (avirulent A7 (74) strain) has been used as a model for virus‐induced demyelination in mice. 155 These mice develop pronounced antiglycolipid reactivity. 156 , 157

Monoclonal antibody (MAb) (373) raised against brain‐derived ‘inactivated’ SFV has been shown to cross‐react with GalS and GalC. 158 This was subsequently shown to neutralize SFV significantly. 158 This antibody also labels SFV, influenza, and measles virus, which replicate in the same brain cell cultures from which the SFV is derived. 74 This indicates that budding viruses take similar glycolipid into their coat if the original host cell of replication is the same.

Prospective studies are essential to link antiglycolipid antibodies with peripheral nerve dysfunction in HIV infection. Data published by De Gasperi et al. have demonstrated such a link with serum and CSF antibodies. 80 But they believe that the anti‐GalS antibodies present in serum are non‐specific, noting that anti‐GalS anti‐bodies are present in the serum of patients without HIV infection and other neurological and immunological disorders, 41 , 42 , 66 , 67 , 159 , 160 , 161 , 162 , 163 , 164 and that their serum sample group did not show any correlation between IgG anti‐GalS levels and CD4 lymphocyte count. As already explained, however, IgG levels do not necessarily decline with declining CD4 lymphocyte count, because the epitope it recognizes is a glycoconjugate (in this case a glycolipid). The CD5‐positive B cells are most likely responsible for the production of antiglycolipid antibodies in HIV‐positive individuals. 38 , 165 Activation of these cells may be due to the glycolipid (most likely GalS) being presented to the immune system in an altered fashion. GalS may become incorporated into viral envelope protein during the course of productive infection (i.e. cells containing GalS within their membrane) and the viral budding process. 74 The integration of GalS into the viral membrane may be the trigger for the immune system to begin synthesizing autoantibodies against the carbohydrate moiety of the molecule.

Recently, evidence has shown that budding HIV‐1 particles produced by infected T cell lines occurs selectively from glycolipid enriched membrane regions (‘lipid rafts’) which include GM1. 166 These investigators demonstrated by confocal microscopy that lipid raft‐associated molecules, including the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)‐anchored proteins Thy‐1 and CD59 and GM1, colocalize with HIV‐1 proteins. Through virus phenotyping using monoclonal antibodies these investigators were also able to indicate that these molecules were incorporated into HIV‐1 particles. Their data suggest that budding of HIV virions through these membrane lipid rafts provides for the incorporation of host cell glycolipids into the viral envelope. This now provides direct evidence that glycolipids (which are possible peripheral nerve myelin neuritogens) are incorporated in budding HIV. Whether this presentation to the peripheral immune cells can elicit an antiglycolipid autoantibody response is yet to be determined.

Experiments in laboratory animals are now required to determine if these antiglycolipid antibodies are capable of directly damaging myelin and whether other factors such as complement, oxygen reactive species and cytokines are also involved in the pathology of inflammatory demyelination in HIV infection. Future work could test the hypothesis that antibodies against peripheral myelin glycolipids in HIV‐infected people induce inflammatory demyelination. Specifically, this research would involve the induction of EAN in Lewis rats by injection of purified antiglycolipid antibodies from HIV‐infected individuals with and without neuropathy. Further experiments would correlate the electrophysiological and morphological data indicating myelin damage.

If these antiglycolipid antibodies are capable of inducing immune demyelination then direct immunofluorescence would show antibodies bound to myelin, and morphological assessment would show intramyelinic swelling and vacuolation. This would most likely be initiated at paranodal areas and Schmidt–Lanterman incisures for anti‐GalS antibodies. 79 These antibodies have also been shown to cause concomitant widening of the outer and inner myelin lamellae of Schwann cell cytoplasm. 79 Electrophysiological abnormalities would include absent F‐waves with preserved distal compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes (≥75% lower limit of normal) as evidence of proximal conduction block, 167 conduction latency, as a sign of axonal degeneration, recorded distally, 168 or similar conduction slowing in both distal and proximal nerve segments for demyelinating neuropathies. 169

CONCLUSION

If antiglycolipid antibodies cause immune demyelination in HIV‐infected patients, a screening ELISA could be used to predict the likelihood of individuals developing peripheral neuropathy. It may also assist in the diagnosis of HIV‐infected patients with underlying subclinical neuropathy. Such patients may benefit by the early institution of treatment such as plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin. A serological screening test may also be of benefit in monitoring disease progress by measuring antiglycolipid antibody titers. It may also be possible to differentiate the neuropathic syndrome according to the specific glycolipid against which antibodies are directed. An example of this is sensorimotor dysfunction with raised anti‐GalS antibody titers.

Of further benefit to the patient would be the identification of the specific CD5+ B cell generating antiglycolipid antibodies. If future research is able to specifically identify these cells it may be also possible to cyto‐apherese patients (specifically for this cell type) with raised titers of antiglycolipid antibodies.

Despite the data presented throughout this report, two main issues still remain to be resolved in identifying the pathogenesis of HIV‐associated inflammatory demyelination: (i) whether the disease is autoimmune; and (ii) whether antiglycolipid autoantibodies are pathogenetic. There exist a set of working criteria which have been derived from a variety of diseases that are generally believed to have antibody‐mediated autoimmune mechanisms. 170 These include: (i) antibody is present in patients with the disease; (ii) antibody interacts with the target antigen; (iii) passive transfer of the antibody produces the disease; (iv) immunization of animals with the antigen produces disease; and (v) reduction of the antibody ameliorates the disease. All of the aforementioned criteria have been described in assessing the role of anti‐GalS antibodies in peripheral neuropathy. Only criteria 1 and 2 were described by De Gasperi et al., 80 Petratos et al. 82 , 83 , 84 and Gisslen et al. 81 in HIV‐infected patients. Passive transfer of these antibodies in HIV‐infected patients into animals would address criterion 3 and has been described in HIV‐negative patients with immune demyelination. 79 Criterion 4 has already been clearly defined in animals 88 and criterion 5 could be trialed in HIV‐infected patients once a clear pathogenetic link of these autoantibodies has been established. For the time being, further research is essential to develop a direct immunopathogenic link for these antiglycolipid antibodies in HIV‐associated peripheral neuropathy. Only then will these diagnostic and therapeutic regimens be implemented within the neurological clinic.

REFERENCES

- 1. Snider WD, Simpson DM, Nielson S, Gold JWM, Metroka CE & Posner JB. Neurological complications of acquired immune deficiency syndrome, analysis of 50 patients. Ann Neurol 1983; 14: 403–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levy RM, Bredesen DE & Rosenblum ML. Neurological manifestations of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), experience at UCSF and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 1985; 62: 475–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. So YT, Holtzman DM, Abrams DI & Olney RK. Peripheral neuropathy associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Neurol 1988; 45: 945–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chavanet P, Solary E & Giroud M et al. Infraclinical neuropathies related to immunodeficiency virus infection associated with higher T‐helper cell count. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1989; 2: 564–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McArthur JC, Sipos E & Cornblath DR et al. Identification of mononuclear cells in CSF of patients with HIV infection. Neurology 1989; 39: 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simpson DM & Wolfe DE. Neuromuscular complications of HIV infection and its treatment. AIDS 1991; 5: 917–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoffman PM, Festoff BW, Giron Lt Jr, Hollenbeck LC, Garruto RM & Ruscetti FW. Isolation of LAV/ HTLV‐III from a patient with amyotropic lateral sclerosis (Letter). N Engl J Med 1985; 313: 324–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Griffin GE, Miller A & Batman P et al. Damage to jejunal intrinsic autonomic nerves in HIV infection. AIDS 1988; 2: 379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bélec L, Gerardi R & Georges AJ et al. Peripheral facial paralysis and HIV infection: Report of four African cases and review of the literature. J Neurol 1989; 236: 411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sillevis Smitt PA & Portegies P. Fisher's syndrome associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1990; 92: 353–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Igloffstein J & Vogel P. Subacute AIDS‐related lumbosacral radiculopathy: A bacterial infection? J Neurol 1991; 238: 239–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mah V, Vartavarian LM, Akers M‐A & Vinters HV. Abnormalities of peripheral nerve in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Ann Neurol 1988; 24: 713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scaravilli F, Sinclair E, Arango J‐C, Manji H, Lucas S & Harrison JG. The pathology of the posterior root ganglia in AIDS and its relationship to the pallor of the gracile tract. Acta Neuropathol 1992; 84: 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kiprov D, Pfaeffl W, Parry G, Lippert R, Lang W & Miller R. Antibody‐mediated peripheral neuropathies associated with ARC and AIDS. Successful treatment with plasmapheresis. J Clin Apheresis 1988; 4: 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cornblath DR, McArthur JC, Kennedy PGE, Witte AS & Griffin JW. Inflammatory demyelinating peripheral neuropathies associated with human T‐cell lymphotrophic virus type III infection. Ann Neurol 1987; 21: 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dalakas MC & Pezeshkpour GH. Neuromuscular diseases associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Ann Neurol 1988; 23 (Suppl.): S38–S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Asbury AK & Cornblath DR. Assessment of current diagnostic criteria for Guillain–Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol 1990; 27 (Suppl.): S21–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parry GJ. Peripheral neuropathies associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Ann Neurol 1988; 23 (Suppl.): S49–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gibbels E & Diederich N. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐related chronic relapsing inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy with multifocal unusual onion bulbs in sural nerve biopsy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1988; 75: 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harvey GK, Gold R, Hartung H‐P & Toyka KV. Non‐neural‐specific T lymphocytes can orchestrate inflammatory peripheral neuropathy. Brain 1995; 118: 1263–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pollard JD, Westland KW & Harvey GK et al. Activated T cells of nonneuronal specificity open the blood– nerve barrier to circulating antibody. Ann Neurol 1995; 37: 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mishra BB, Sommers W, Koski CL & Greenstein JI. Polyneuropathy in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol 1985; 18: 131–132. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kiprov DD, Lippert R & Miller RG et al. The use of plasmapheresis, lymphocytapheresis, and staph protein‐A immunoadsorption as an immunomodulatory therapy in patients with AIDS and AIDS‐related conditions. J Clin Apheresis 1986; 3: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cornblath DR, Griffin DE, Welch D, Griffin JW & McArthur JC. Quantitative analysis of endoneurial T‐cells in human sural nerve biopsies. J Neuroimmunol 1990; 26: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cruz Martinez A, Rabano J, Villoslada C & Cabello A. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy as first manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1990; 30: 379–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koski CL, Franko MC, Hudson CS & Shin ML. Incorporation of P0 protein into liposomes: Demonstration of a two‐domain structure by immunochemical and PAGE analysis. J Neurochem 1984; 42: 856–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cruz M, Ernerudh J, Olsson T, Hojeberg B & Link H. Occurrence and isotype of antibodies against peripheral nerve myelin in serum from patients with peripheral neuropathy and healthy controls. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988; 51: 820–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koski CL, Chou DK & Jungalwala FB. Anti‐peripheral myelin antibodies in Guillain–Barré syndrome bind a neutral glycolipid of peripheral myelin and cross‐react with Forssman antigen. J Clin Invest 1989; 84: 280–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vrethem M, Lindvall B, Holmgren H, Henriksson KG, Lindstrom F & Ernerudh J. Neuropathy and myopathy in primary Sjogren's syndrome: Neurophysiological, immunological and muscle biopsy results. Acta Neurol Scand 1990; 82: 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Duarte F, Binet S, Lacomblez L, Bouche P, Preud'homme JL & Meininger V. Quantitative analysis of monoclonal immunoglobulins in serum of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 1991; 104: 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wirguin I, Brennar T, Steinitz M & Abramsky O. In vitro synthesis of antibodies to myelin antigens by Epstein– Barr virus‐transformed B lymphocytes from patients with neurologic disorders. J Neurol Sci 1991; 104: 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lach B, Rippstein P, Atack D, Afar DE & Gregor A. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of monoclonal IgM antibodies in gammopathy associated with peripheral demyelinating neuropathy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1993; 85: 298–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mithen FA, Ilyas AA, Birchem R & Cook SD. Effects of Guillain–Barré sera containing antibodies against glycolipids in cultures of rat Schwann cells and sensory neurons. J Neurol Sci 1992; 112: 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suarez GA & Kelly Jj Jr. Polyneuropathy associated with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: Further evidence that IgM‐MGUS neuropathies are different than IgG‐MGUS. Neurology 1993; 43: 1304–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Willison HJ, Paterson G, Kennedy PGE & Veitch J. Cloning of human anti‐GM1 antibodies from motor neuropathy patients. Ann Neurol 1994; 35: 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Petratos S, Turnbull VJ, Papadopoulos R, Ayers M & Gonzales MF. High titre IgM anti‐sulphatide anti‐bodies in patients with IgM paraproteinaemia and inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Immunol Cell Biol 2000; 78: 124–132.DOI: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dyck PJ, O'brien PC & Oviatt KF et al. Prednisone improves chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculneuropathy. Ann Neurol 1982; 11: 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dyck PJ, Daube J & O'brien P et al. Plasma exchange in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy. N Engl J Med 1986; 314: 461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vedeler CA & Nyland H. Plasma exchange in Guillain–Barré syndrome: Effect on anti‐peripheral nerve myelin antibodies. Acta Neurol Scand 1990; 82: 147–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hauttecoeur B, Schmitt C, Dubois C, Danon F & Brouet JC. Reactivity of human monoclonal IgM with nerve glycosphingolipids. Clin Exp Immunol 1990; 80: 181–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fredman P, Vedeler CA, Nyland H, Aarli JA & Svennerholm L. Antibodies in sera from patients with inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy react with ganglioside LM1 and sulphatide of peripheral nerve myelin. J Neurol 1991; 238: 75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ilyas AA, Mithen FA, Chen Z‐W & Cook SD. Search for antibodies to neutral glycolipids in sera of patients with Guillain–Barré syndrome. J Neurol Sci 1991; 102: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Van Den Berg LH, Lankcamp CLAM & De Jager AE et al. Anti‐sulphatide antibodies in peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1993; 56: 1164–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Santoro M, Uncini A & Corbo M et al. Experimental conduction block induced by serum from a patient with anti‐GM1 antibodies. Ann Neurol 1992; 31: 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rijkers GT & Zegers BJM. Immunoregulation in man. Neth J Med 1991; 39: 222–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Banchereau J & Rousset F. Human B lymphocytes: Phenotype, proliferation, and differentiation. Adv Immunol 1992; 52: 125–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Khalili‐Shirazi A, Hughes RAC, Brostoff SW, Linington C & Gregson N. T cell responses to myelin proteins in Guillain–Barré syndrome. J Neurol Sci 1992; 111: 200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ishioka GY, Lamont AG & Thomson D et al. MHC interaction and T cell recognition of carbohydrates and glycopeptides. J Immunol 1992; 148: 2446–2451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Snapper CM, McIntyre TM & Mandler R et al. Induction of IgG3 secretion by interferon γ: A model for T cell‐independent class switching in response to T cell‐independent type 2 antigens. J Exp Med 1992; 175: 1367–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Latov N. Neuropathy and anti‐GM1 antibodies. Ann Neurol 1990; 27 (Suppl.): S41–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hayakawa K, Carmack CE, Shinton SA & Hardy RR. Selection of autoantibody specificities in the Lyl‐1 B subset. Ann NY Acad Sci 1992; 651: 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hardy RR & Hayakawa K. CD5 B cells, a fetal B cell lineage. Adv Immunol 1994; 55: 297–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Porcelli S, Morita CT & Brenner MB. CD1b restricts the response of human CD4–8– T lymphocytes to a microbial antigen. Nature 1992; 360: 593–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Porcelli SA & Modlin RL. THE CD1 SYSTEM: Antigen‐presenting molecules for T cell recognition of lipids and glycolipids. Annu Rev Immunol 1999; 17: 297–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Khalili‐Shirazi A, Gregson NA, Londei M, Summers L & Hughes RA. The distribution of CD1 molecules in inflammatory neuropathy. J Neurol Sci 1998; 158: 154–163.DOI: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00121-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shamshiev A, Donda A, Carena I, Mori L, De Kappos L & Libero G. Self glycolipids as T‐cell antigens. Eur J Immunol 1999; 29: 1667–1675.DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Braun PE, Frail DE & Latov N. Myelin‐associated glycoprotein is the antigen for a monoclonal IgM in polyneuropathy. J Neurochem 1982; 39: 1261– 1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Steck AJ, Murray N, Meier C, Page N & Peruisseau G. Demyelinating neuropathy and monoclonal IgM antibody to myelin‐associated glycoprotein. Neurology 1983; 33: 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ilyas AA & Davison AN. Cellular hypersensitivity to gangliosides and myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 1983; 59: 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ilyas AA, Quarles RH & MacIntosh TD et al. IgM in human neuropathy related to paraproteinemia binds to a carbohydrate determinant in the myelin‐associated glycoprotein and to a ganglioside. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1984; 81: 1225–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chou DKH, Ilyas AA, Evans JE, Costello C, Quarles RH & Jungalwala FB. Structure of sulfated glucuronyl glycolipids in the nervous system reacting with HNK‐1 antibody and some IgM paraproteins in neuropathy. J Biol Chem 1986; 261: 11 717–11 725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ariga T, Kohriyama T & Freddo L et al. Characterization of sulfated glucuronic acid containing glycolipids reacting with IgM M‐proteins in patients with neuropathy. J Biol Chem 1987; 262: 848–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hays A, Latov N, Takatsu M & Sherman WH. Experimental demyelination of nerve induced by serum of patients with neuropathy and an anti‐MAG IgM M‐protein. Neurology 1987; 37: 242–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Willison HJ, Trapp BD, Bacher JD, Dalakas M, Griffin JW & Quarles RH. Demyelination induced by intraneural injection of human anti‐myelin‐asociated glycoprotein antibodies. Muscle Nerve 1988; 11: 1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tatum AH. Experimental paraprotein neuropathy, demyelination by passive transfer of human IgM anti‐myelin‐associated glycoprotein. Ann Neurol 1993; 33: 502–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pestronk A, Li F & Griffin J et al. Polyneuropathy syndromes associated with serum antibodies to sulfatide and myelin‐associated glycoprotein. Neurology 1991; 41: 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Quattrini A, Carbo M & Dhaliwal SK et al. Anti‐sulfatide antibodies in neurological disease, binding to rat dorsal root ganglia neurons. J Neurol Sci 1992; 112: 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Uemura K, Yuzawa‐Watanabe M, Kitazawa N & Taketomi T. Immunochemical studies of lipids: Reactions of anti‐sulfatide antibodies with sulfatide in liposomal and myelin membranes. J Biochem 1979; 87: 1221–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Newkirk MM, Mageed RA, Jefferis R, Chen PP & Capra JD. Complete amino acid sequences of variable regions of two human IgM rheumatoid factors, BOR and KAS of the Wa idiotypic family, reveal restricted use of heavy and light chain variable and joining region gene segments. J Exp Med 1987; 166: 550–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Silverman GJ & Carson DA. Structural characterization of human monoclonal cold agglutinins: Evidence for a distinct primary sequence‐defined Vh4 idiotype. Eur J Immunol 1990; 20: 351–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Radic MZ, Mascelli MA, Erickson J, Shan H & Weigert M. Ig H and L chain contribution to autoimmune specificities. J Immunol 1991; 146: 176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Spatz LA, Williams M, Brender B, Desai R & Latov N. DNA sequence analysis and comparison of the variable heavy and light chain regions of two IgM monoclonal anti‐MAG antibodies. J Neuroimmunol 1992; 36: 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lee K‐W, Inghrami G, Spatz LA, Knowles DM & Latov N. The B‐cells that express anti‐MAG antibodies in neuropathy and non‐malignant monoclonal gammopathy belong to the CD5 subpopulation. J Neuroimmunol 1991; 31: 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pathak S, Illavia SJ & Khalili‐Shirazi A. Immunoelectron microscopical labelling of a glycolipid in the envelopes of brain cell derived budding viruses, Semliki Forest, influenza and measles, using a monoclonal antibody directed chiefly against galactocerebroside made by SFV immunization. J Neurol Sci 1990; 96: 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Olsson Y. Microenvironment of the peripheral nervous system under normal and pathological conditions. Crit Rev Neurobiol 1990; 5: 265–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Holt GD, Pangburn MK & Ginsburg V. Properdin binds to sulfatide (Gal (3‐SO4) β1–1Cer) and has a sequence homology with other proteins that bind sulfated glycoconjugates. J Biol Chem 1990; 265: 2852–2855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wu CSC, Lee NM, Loth HH & Yang JT. Competitive binding of dynorphin‐(1–13) and β‐endorphin to cerebroside sulfate in solution. J Biol Chem 1986; 261: 3687–3691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dupouey P, Zalc B, Lefroit‐Joly M & Gomes D. Localization of galactosylceramide and sulfatide at the surface of the myelin sheath: An immunofluorescence study in liquid medium. Cell Mol Biol 1979; 25: 269–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Nardelli E, Bassi A, Mazzi G, Anzini P & Rizzuto N. Systemic passive transfer studies using IgM monoclonal antibodies to sulfatide. J Neuroimmunol 1995; 63: 29–37.DOI: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00125-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. De Gasperi R, Gama Sosa A & Patarca R et al. Intrathecal synthesis of anti‐sulfatide IgG is associated with peripheral nerve disease in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1996; 12: 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gisslen M, Lekman A & Fredman P. High levels in serum, but no signs of intrathecal synthesis of anti‐sulfatide antibodies in HIV‐1 infected individuals with or without central nervous system complications. J Neuroimmunol 1999; 94: 153–156.DOI: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00244-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Petratos S, Turnbull VJ, Papadopoulos R, Ayers M & Gonzales MF. Antibodies against peripheral myelin glycolipids in people with HIV infection. Immunol Cell Biol 1998; 76: 535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Petratos S, Turnbull VJ, Papadopoulos R, Ayers M & Gonzales MF. High titre anti‐sulphatide antibodies in HIV infected individuals. Neuroreport 1999; 10: 2557–2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Petratos S, Turnbull VJ, Papadopoulos R, Ayers M & Gonzales MF. Peripheral nerve binding patterns of high titre anti‐sulphatide antibodies present in plasma samples from HIV‐infected individuals. Neuroreport 1999; 10: 1659–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Katz IR, Krown SE, Safai B, Oettgen HF & Hoffmann MK. Antigen‐specific and polyclonal B‐cell responses in patients with AIDS. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1986; 39: 359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lane HC, Masur H, Edgar LC, Whalen G, Rook AH & Fauci AS. Abnormalities of B‐cell activation and immunoregulation in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 1983; 309: 453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Massabki PS, Accetturi C, Nishie IA, Da Silva NP, Sato EI & Andrade LEC. Clinical implications of autoantibodies in HIV infection. AIDS 1997; 11: 1845–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Qin Z & Guan Y. Experimental polyneuropathy produced in guinea‐pigs immunized against sulfatide. Neuroreport 1997; 8: 2867–2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Pestronk A, Cornblath DR & Ilyas AA et al. A treatable multifocal motor neuropathy with antibodies to GM1 ganglioside. Ann Neurol 1988a; 24: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Pestronk A, Adams RN & Clawson L et al. Serum antibodies to GM1 ganglioside in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 1988; 38: 1457–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Shy ME, Evans VA & Lublin FD et al. Antibodies to GM1 and GD1b in patients with motor neuron disease without plasma cell dyscrasia. Ann Neurol 1989; 25: 511–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Quarles RH, Ilyas AA & Willison HJ. Antibodies to gangliosides and myelin proteins in Guillain– Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol 1990; 27 (Suppl.): S48–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ponzin D, Menegus AM, Kirschner G, Nunzi G, Fiori MG & Raine CS. Effects of gangliosides on the expression of autoimmune demyelination in the peripheral nervous system. Ann Neurol 1991; 30: 678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Adams D, Kuntzer T & Burger D et al. Prediction value of anti‐GM1 ganglioside antibodies in neuromuscular diseases, a study of 180 sera. J Neuroimmunol 1991; 32: 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Heidenreich F, Leifeld L & Jovin T. T cell‐dependent activity of ganglioside GM1‐specific B cells in Guillain–Barré syndrome and multifocal motor neuropathy in vitro. J Neuroimmunol 1994; 49: 97– 108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, Machinami R & Kanazawa I. Serum anti‐GQ1b IgG antibody is associated with ophthalmoplegia in Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain–Barré syndrome, clinical and immunohistochemical studies. Neurology 1993; 43: 1911–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Willison HJ, Veitch J, Paterson G & Kennedy PGE. Miller Fisher syndrome is associated with serum antibodies to GQ1b ganglioside. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1993; 56: 204–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Yuki N, Sato S, Tsuji S, Ohsawa T & Miyatake T. Frequent presence of anti‐GQ1b antibody in Fisher's syndrome. Neurology 1993; 43: 414–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ilyas AA, Willison HJ & Quarles RH et al. Serum antibodies to gangliosides in Guillain–Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol 1988; 23: 440–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Svennerholm L & Fredman P. Antibody detection in Guillain–Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol 1990; 27 (Suppl.): S36–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Witkin SS, Sonnabend J, Richards JM & Purtilo DT. Induction of antibody to asialo‐GM1 by spermatozoa and its occurrence in the sera of homosexual men with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 1983; 54: 346–350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Sorice M, Griggi T & Circella A et al. Cerebrospinal fluid antiganglioside antibodies in patients with AIDS. Infection 1995; 23: 288–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Vishnubhakat SM & Beresford HR. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in HIV disease: Prospective study of 40 patients. Neurology 19088; 38 (Suppl. 1): 350. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Janssen RS, Saykin AJ & Kaplan JE et al. Neurological complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection in patients with lymphadenopathy syndrome. Ann Neurol 1988; 23: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hall CD, Snyder CR, Messenheimer JA & Wilkins JW et al. Peripheral neuropathy in a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus‐infected patients. Incidence and relationship to other nervous system dysfunction. Arch Neurol 1991; 48: 1273– 1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Winer JB, Bang B & Clarke JR et al. A study of neuropathy in HIV infection. Q J Med 1992; 83: 473–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Saida K, Saida T, Brown MJ & Silberberg DH. In vivo demyelination induced by intraneural injection of anti‐galactocerebroside serum, a morphological study. Am J Pathol 1979; 95: 99–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Morell P & Radin NS. Synthesis of cerebroside by brain from uridine diphosphate galactose and ceramide containing hydroxy fatty acid. Biochemistry 1969; 8: 506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Morell P, Constantino‐Ceccarini E & Radin NS. The biosynthesis by brain microsomes of cerebrosides containing nonhydroxy fatty acids. Arch Biochem Biophys 1970; 141: 738–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Basu S, Schultz AM, Basu M & Roseman S. Enzymatic synthesis of galactocerebroside by a galactosyl‐transferase from embryonic chick brain. J Biol Chem 1971; 246: 4272–4279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Hughes RAC, Gray IA & Gregson NA et al. Immune responses to myelin antigens in Guillain–Barré syndrome. J Neuroimmunol 1984; 6: 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Rostami AM, Burns JB, Eccleston PA, Manning MC, Lisak RP & Silberberg DH. Search for antibodies to galactocerebroside in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid in human demyelinating disorders. Ann Neurol 1987; 22: 381–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Koski CL, Gratz E, Sutherland J & Mayer RF. Clinical correlation with anti‐peripheral‐nerve myelin antibodies in Guillain–Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol 1986; 19: 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Norton WT & Poduslo SE. Myelination in rat brain. Method of myelin isolation. J Neurochem 1973; 21: 749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Nadkarni N & Lisak RP. Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) with bilateral optic neuritis and central white matter disease. Neurology 1993; 43: 842–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Kinoshita A, Hayashi M, Miyamoto K, Oda M & Tanabe H. Inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculitis in a patient with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 60: 87–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Amit R, Shapira Y, Blank A & Aker M. Acute, severe, central and peripheral nervous system combined demyelination. Pediatr Neurol 1986; 2: 47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Amit R, Glick B, Itzchak Y, Dgani Y & Meyeir S. Acute severe combined demyelination. Childs Nerv Syst 1992; 8: 354–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Schoene WC, Carpenter S, Behan PO & Geschwind N. ‘Onion bulb’ formations in the central and peripheral nervous system in association with multiple sclerosis and hypertrophic polyneuropathy. Brain 1977; 100: 755–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ro YI, Alexander CB & Oh SJ. Multiple sclerosis and hypertrophic demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 1983; 6: 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Rosenberg NL & Bourdette D. Hypertrophic neuropathy and multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1983; 33: 1361–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Rubin M, Karpati G & Carpenter S. Combined central and peripheral myelinopathy. Neurology 1987; 37: 1287–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Zee PC, Cohen BA, Walczak T & Jubelt B. Peripheral nervous system involvement in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1991; 41: 457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Hagberg L, Malmvall B‐E, Svennerholm L, Alestig K & Norkrans G. Guillain–Barré syndrome as an early manifestation of HIV central nervous system infection. Scand J Infect Dis 1986; 18: 591–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Van Der Lelie L, Lange IM & Vos II. Autoimmunity against blood cells in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Haematol 1987; 67: 109–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Fauci AS. The human immunodeficiency virus infectivity and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science 1988; 239: 617–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Houf SA. Neuroimmunology of human immunodeficiency virus infection In: Rosenblum ML, Levy RM, Bredesen DE (eds) AIDS and the Nervous System. New York: Raven Press, 1988; 347–357. [Google Scholar]

- 128. Lipkin WI, Parry G, Kiprov D & Abrams D. Inflammatory neuropathy in homosexual men with lymphadenopathy. Neurology 1985; 35: 1479–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Gonzales‐Scarano F & Tyler KL. Molecular pathogenesis of neurotropic viral infections. Ann Neurol 1987; 22: 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. De La Monte SM, Gabuzda DH & Ho DD et al. Peripheral neuropathy in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol 1988; 23: 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Argall KG, Armati PJ, Pollard JD, Watson E & Bonner J. Interactions between CD4+ T‐cells and rat Schwann cells in vitro. 1. Antigen presentation by Lewis rat Schwann cells to P2‐specific CD4+ T‐cell lines. J Neuroimmunol 1992; 40: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Stowring L, Haase AT & Petursson G et al. Detection of visna virus antigens and RNA in glial cells in foci of demyelination. Virology 1985; 141: 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Porter DD, Larsen AE & Porter HG. The pathogenesis of Aleutian disease of mink. 3. Immune complex arteritis. Am J Pathol 1973; 71: 331–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Webb HE & Fazakerley JK. Can viral envelope glycolipids produce autoimmunity, with reference to the CNS and multiple sclerosis? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 1984; 10: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Harouse JM, Bhat S & Spitalnik SL et al. Inhibition of entry of HIV‐1 in neural cell lines by antibodies against galactosyl ceramide. Science 1991; 253: 320–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Ebel F, Schmitt E, Peter Katalinic J, Kniep B & Muhlradt PF. Gangliosides: Differentiation markers for murine T helper lymphocyte subpopulations TH1 and TH2. Biochemistry 1992; 31: 12 190–12 197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Seddiki N, Ben Younes‐Chennoufi A & Benjouad A et al. Membrane glycolipids and human immunodeficiency virus infection of primary macrophages. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1996; 12: 695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Yahi N, Baghdiguian S, Moreau M & Fantini J. Galactosyl ceramide (or a closely related molecule) is the receptor for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on human colon epithelial HT29 cells. J Virol 1992; 66: 4848–4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Fantini J, Cook DG, Nathanson N, Spitalnik SL & Gonzales‐Scarano F. Infection of colonic epithelial cell lines by type 1 human immunodeficiency virus is associated with cell surface expression of galactosylceramide, a potential alternative gp120 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90: 2700–2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Almeida JD & Waterson AP. Virological aspects of neurological disease. Postgrad Med J 1969; 45: 351–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Reilly Ca Jr & Schloss GT. The erythrocyte as virus carrier in Friend and Rauscher virus leukemias. Cancer Res 1971; 31: 841–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Cox KO & Keast D. ‘Forbidden clones’ and autoimmunity. Lancet 1973; 1: 1123–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Steck AJ, Tschannen R & Schaefer R. Induction of antimyelin and antioligodendrocyte antibodies by vaccinia virus. An experimental study in the mouse. J Neuroimmunol 1981; 1: 117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Rook GA & Webb HE. Antilymphocyte serum and tissue culture used to investigate role of cell‐mediated response in viral encephalitis in mice. BMJ 1970; 4: 210–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Klenk HD & Choppin PW. Glycosphyngolipids of plasma membrane of cultured cells and an enveloped virus (SV5) grown in these cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1970; 66: 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Soule DW, Marinetti GV & Morgan HR. Studies of the hemolysis of red blood cells by mumps virus. IV. Quantitative study of changes in red blood lipids and of virus lipids. J Exp Med 1959; 110: 93– 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Kates M, Allison AC, Tyrrell DAJ & James AT. Lipids of influenza virus and their relation to those of the host cell. Biochim Biophys Acta 1961; 52: 455–466. [Google Scholar]

- 148. Blough HA & Merlie JP. The lipids of incomplete influenza virus. Virology 1970; 40: 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Quigley JP, Rifkin DB & Reich E. Phospholipid composition of Rous sarcoma virus, host cell membranes and other enveloped RNA viruses. Virology 1971; 46: 106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Hirschberg CB & Robbins PW. The glycolipids and phospholipids of Sindbis virus and their relation to the lipids of the host cell plasma membrane. Virology 1974; 61: 602–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Heydrick FP, Comer JF & Wachter RF. Phospholipid composition of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. J Virol 1971; 7: 642–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Renkonen O, Kaarainen L, Simons K & Gahmberg CG. The lipid class composition of Semliki Forest virus and of plasma membranes of the host cells. Virology 1971; 46: 318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Laine R, Kettunen ML, Gahmberg CG, Kääriäinen L & Renkonon O. Fatty chains of different lipid classes of Semliki Forest virus and host cell membranes. J Virol 1972; 10: 433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Luukkonen A, Kääriäinen L & Renkonon O. Phospholipids of Semliki Forest virus grown in cultured mosquito cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1976; 450: 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Webb HE, Chew L & Jagelman S et al. Semliki Forest virus infections in mice as a model for studying acute and chronic central nervous system virus infections in mice In: Rose F (ed.) Clinical Neuroimmunology. London: Blackwell Science, 1979; 369–390. [Google Scholar]

- 156. Khalili‐Shirazi A, Gregson N & Webb HE. Immunological relationship between a demyelinating RNA enveloped budding virus (Semliki Forest) and brain glycolipids. J Neurol Sci 1986; 76: 91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Amor S & Webb HE. CNS pathogenesis following a dual virus infection with Semliki Forest (Alphavirus) and Langat (Flavivirus). Br J Exp Pathol 1988; 69: 197–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]