ABSTRACT

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a re‐emerging mosquito‐borne alphavirus that recently caused large epidemics in islands in, and countries around, the Indian Ocean. There is currently no specific drug for therapeutic treatment or for use as a prophylactic agent against infection and no commercially available vaccine. Prohibitin has been identified as a receptor protein used by chikungunya virus to enter mammalian cells. Recently, synthetic sulfonyl amidines and flavaglines (FLs), a class of naturally occurring plant compounds with potent anti‐cancer and cytoprotective and neuroprotective activities, have been shown to interact directly with prohibitin. This study therefore sought to determine whether three prohibitin ligands (sulfonyl amidine 1 m and the flavaglines FL3 and FL23) were able to inhibit CHIKV infection of mammalian Hek293T/17 cells. All three compounds inhibited infection and reduced virus production when cells were treated before infection but not when added after infection. Pretreatment of cells for only 15 minutes prior to infection followed by washing out of the compound resulted in significant inhibition of entry and virus production. These results suggest that further investigation of prohibitin ligands as potential Chikungunya virus entry inhibitors is warranted.

Keywords: Chikungunya virus, entry inhibitor, flavaglines, sulfonyl amidines

Abbreviations

- Ae.

Aedes

- CC50

50% cytotoxicity concentration

- CHIKF

Chikungunya fever

- CHIKV

Chikungunya virus

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- E

envelope

- ECSA

East Central and South Africa

- FL

flavagline

- IC50

50% inhibitory concentration

- MTT

3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- nsP

nonstructural protein(s)

- pfu

plaque forming unit

- PHB

prohibitin

Chikungunya virus, the cause of CHIKF, is transmitted to humans by the bites of infected Ae mosquitos, most commonly Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus; CHIKV‐infected patients develop symptoms some 2–4 days (range 1 to 12 days) days after being bitten 1. Clinically, the disease is similar to dengue fever, patients present with a sudden febrile illness with rash, headache, edema of the extremities, gastrointestinal complaints, myalgia, and polyarthralgia (a hallmark of CHIKV infection) that frequently persists for two or more months 1.

Chikungunya virus belongs to the Alphavirus genus, family Togaviridae. The genome is an 11.8 kb positive sense single stranded RNA with a 5′‐methylguanylate cap and a 3′‐poly A tail 2. The genome possesses two open reading frames, which encode for four nsPs (nsP1–nsP4), three structural proteins (capsid, E1 and E2) and two proteins of ill‐defined function (E3 and 6 K). The CHIKV virion is approximately 70 nm in diameter and contains a nucleocapsid surrounded by a lipid bilayer envelope in which are embedded 80 trimeric spikes composed of 240 heterodimers of the E1 and E2 glycoproteins 3. The 52 kDa E1 glycoprotein mediates fusion of virus with host cell membrane, whereas the 50 kDa E2 glycoprotein is responsible for receptor binding 2.

Chikungunya fever was first formally described after an outbreak in Tanzania in 1952 4. The virus was first isolated from the same outbreak 5 and was subsequently shown to be present in several parts of Africa and South and Southeast Asia 6. An outbreak of CHIKF in Kenya in 2004 7 spread to the Indian Ocean islands of Comoros and Seychelles in 2005 8 and then to Mauritius and La Reunion 9. Some 266,000 cases of CHIKF were believed to have occurred in La Reunion 10, 11 and outbreaks were subsequently reported in India starting from 2005, and later in Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand and other parts of Southeast Asia 12, 13, 14. CHIKV has now been reported in many countries, and has caused particular concern through cases of autochthonous transmission in European countries 15.

A number of cell types, including epithelial, endothelial, fibroblast and monocyte‐derived macrophage, are susceptible to CHIKV infection, whereas monocytes, lymphocytes, NK cells and monocyte‐derived dendritic cells are reportedly not susceptible to CHIKV infection 16, 17. However, one study has shown CHIKV infection and replication in monocytes 18. The mechanism of entry of the virus remains somewhat unclear. Sourisseau and colleagues proposed that CHIKV entry (into Hela cells) was via a clathrin‐dependent pathway16; however, Bernard and colleagues proposed that entry was via a clathrin‐independent, Eps‐15‐dependent endocytic pathway 19. Both studies proposed that a cholesterol and pH dependent step is required for infection 16, 19.

In a recent study, PHB1 was identified as a receptor protein for CHIKV entry into mammalian cells 20. PHB1 and its homologue PHB2 are pleiotropic scaffold proteins that act as signaling hubs 21. Multiple heterodimers of PHB1 and PHB2 organize into large, ring‐like structures with diameters of 20–25 nm in the mitochondria 22, 23, 24, whereas in the cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus and plasma membrane PHB forms heterodimers with signaling proteins to regulate many aspect of cell physiology, including mitochondrial biogenesis, survival, metabolism and cell division 25.

Cell surface‐expressed PHB has been shown to act as an interacting molecule for the Vi polysaccharide of Salmonella typhi 26, wherease PHB expressed on the surfaces of insect cells has been shown to be a receptor for dengue virus 27 and an interacting protein for Cry4B, one of the major insecticidal toxins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis 28.

There is currently no specific antiviral treatment or commercially available vaccine to either protect against or treat CHIKV infections, although there are a number of vaccine development programs 29, 30, 31, 32. Flavaglines are a family of plant natural products that have potent anticancer and neuro‐ and cardio‐protective properties 33, 34, 35; studies have shown that prohibitins are directly interacting targets of this class of molecules 36. The synthetic sulfonyl amidine 1 m, which inhibits bone remodeling, also reportedly binds PHB1 37. This study therefore sought to determine whether the synthetic flavaglines FL3 and FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m are able to interfere with the CHIKV–prohibitin interaction that occurs at the receptor binding stage of CHIKV infection of mammalian cells.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

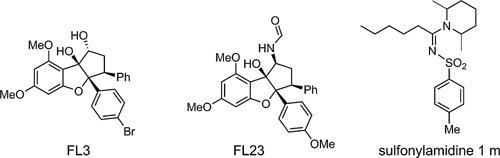

Compounds

The structures of flavaglines FL3 (C25H23BrO5; MW: 483.36), FL23 (C26H24BrNO5; MW 510.38) and sulfonyl amidine 1 m (C20H32N2O2S; MW 364.55) are shown in Figure 1. FL3 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m were synthesized according to described procedures 21, 38. The purity of these compounds was over 95% based on reversed‐phase HPLC analyses (Hypersil Gold column 30 1 mm, C18, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) under the following conditions: flow rate, 0.3 mL/min; buffer A, CH3CN, buffer B, 0.01% aqueous trifluoroethanoic acid; gradient, 98–10% buffer B over 8 min (detection, λ = 220/254 nm). The compounds were initially dissolved in DMSO as stock and serially diluted in DMEM for working solutions with a final DMSO concentration of less than 0.1%. Vehicle/DMEM used as a control consisted of DMSO diluted to 0.1% in DMEM.

Figure 1.

Structures of flavagline FL3, FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m.

Cell culture and virus propagation

The human embryonic kidney cell line Hek293T/17 (ATCC Cat No. CRL‐11268) was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated FBS and 100 units/mL of penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C with 5%CO2, whereas Vero (ATCC Cat No. CCL‐81) was cultured with 5% FBS and 100 units/mL of penicillin/streptomycin.

The CHIKV used in this study was a Thai isolate of an ECSA strain with genotype E1:226V ECSA; it was propagated and stock virus produced as described previously 17. Stock titers were determined by standard plaque assays, undertaken essentially as described elsewhere 17, 20.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed essentially as described previously 39 by incubating Hek293T/17 cells with 20 pfu/cell CHIKV for 1 hr at 4 °C in the presence or absence of various compounds at 100 nM. The cells were subsequently fixed by treatment with pre‐cooled 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min and then incubated with a 1:100 dilution of a mouse monoclonal anti‐alphavirus (3581) antibody (STSC‐58088, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and a 1:200 dilution of a goat polyclonal anti‐ PHB‐1 antibody (SC‐18196, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by incubation with a 1:150 dilution of an Alexa Fluor 488 labeled donkey anti‐mouse IgG antibody (A11029, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and a 1:150 dilution of an Alexa Fluor 568 labeled donkey anti‐goat IgG antibody (A11057, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were visualized under an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Shinjuku‐ku, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with Olympus FluoView Software v. 1.6. Image analysis and calculation of Pearson correlation coefficients and CIs were carried out as described previously 40.

Cell viability analysis

Cell viability was determined using a Vybrant MTT Cell proliferation assay kit (V13154, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The percentage cell viability was calculated from the average of eight sample measurements compared with negative control (vehicle/DMEM).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry to determine cellular infection with CHIKV was undertaken exactly as described elsewhere 17. The cells were analyzed on a BD FACalibur cytometer (Becton Dickinson, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and data analyzed using CELLQuestTM software.

Analysis of apoptosis

Analysis of induction of apoptosis in response to CHIKV infection was performed exactly as described elsewhere 17. As a positive control, Hek293T/17 cells were treated with 5% DMSO diluted in complete DMEM for 24 hrs. All experiments were undertaken independently in triplicate.

Assay of effect of compounds on CHIKV infection

Hek293T/17 cells were seeded in six well culture plates and grown under standard conditions until the cells reached approximately 90% confluence. The cells were then pre incubated with different concentrations of FL3, FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m finally diluted in DMEM for the times stated, or incubated with the equivalent volume of vehicle/DMEM, after which they were washed and incubated with 10 pfu/cell of CHIKV ECSA genotype (E1:226V) in the absence of the drug. Following infection, cells were washed three times with DMEM, after which they were re‐incubated in complete medium containing the compound or the equivalent of vehicle/DMEM. At 20 hrs the cell pellets were analyzed by flow cytometry and the supernatant by standard plaque assay to determine CHIKV titers. In some experiments, compounds were added at designated times after the virus infection step. All experiments were undertaken independently in triplicate, with duplicate plaque assays.

Assay of effect of pulse addition of compounds on CHIKV infection

Hek293T/17 cells were seeded in six wells culture plates and grown under standard conditions until the cells reached approximately 90% confluence. Cells were then pre incubated with different concentrations of FL3, FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m finally diluted in DMEM or incubated with the equivalent volume of vehicle/DMEM for 15 minutes, after which they were washed twice with DMEM and subsequently incubated with 10 pfu/cell of CHIKV ECSA genotype (E1:226V) in the absence of the drug. Following infection cells were washed three times with DMEM, after which they were re‐incubated in complete medium. At 20 hrs the cell pellets were analyzed by flow cytometry and the supernatant analyzed by standard plaque assay to determine CHIKV titers. All experiments were performed independently in triplicate, with duplicate plaque assays.

Assay for virucidal activity

Stock CHIKV ECSA genotype (E1:226V) was incubated directly with different concentrations of FL3, FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m as indicated for 1 hr. The titers of the virus were then directly determined by standard plaque assay. These preparations were also used to infect Hek293T/17 cells that had been cultured in six well plates until they had reached approximately 90% confluence.

Statistical analysis

Viral infection and viral production data were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism program (GrapPad Software). Statistical analysis of significance was undertaken by a paired sample t‐tests using SPSS (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA); P < 0.05 was considered significant. CC50 and IC50 values were calculated using freeware ED50plus (v1.0) software (http://sciencegateway.org/protocols/cellbio/drug/data/ed50v10.xls).

RESULTS

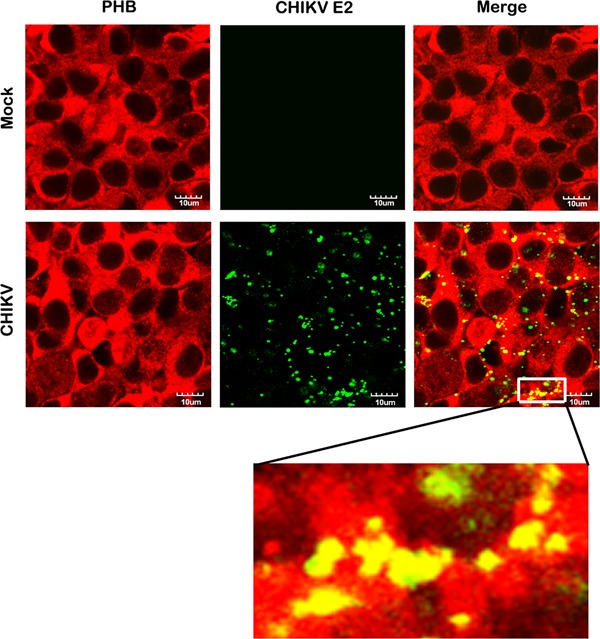

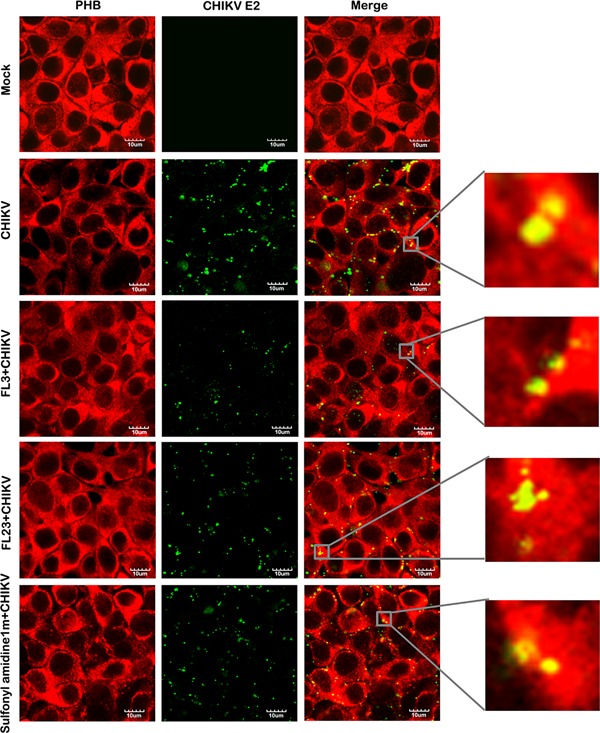

Colocalization between prohibitin and CHIKV E2 protein

In our previous study identifying PHB as a CHIKV receptor protein, the majority of the analysis was undertaken in CHME‐5 (human microglial) cells 20. To investigate the effect of flavaglines on CHIKV entry in this study, we decided to use Hek293T/17 cells because these cells are more suitable for flow cytometry analysis. Our previous study showed that Hek293T/17 cells expressed PHB, which was capable of binding CHIKV 20. We therefore initially confirmed that CHIKV colocalized with PHB on the surfaces of Hek293T/17 cells, as previously shown for CHME‐5 cells 20. As shown in Figure 2, we found cell surface expression of PHB and distinct colocalization between PHB and CHIKV.

Figure 2.

Colocalization of CHIKV E2 protein with PHB. (a) Hek293T/17 cells were grown on glass slides and incubated with CHIKV or mock incubated and examined for the cell surface colocalization of PHB (red) and CHIKV E2 protein (green). Fluorescent signals were observed using an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal microscope. Scale bar for magnification is shown. Representative, non‐contrast adjusted, unmerged and merged images are shown.

Evaluation of cytotoxicity, cell death and virucidal activity

We incubated Hek293T/T17 cells individually with various concentrations of each compound under investigation for 24 hrs, after which we assessed cell viability using an MTT assay. We calculated the percentage cell viability from the average of eight replicates and compared it with negative (vehicle/DMEM) and positive (5% DMSO) controls. We found that after 24 hrs incubation, cell viability for FL3, FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m at concentrations of 20 nM or less (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 5, 10 and 20 nM) was comparable to that of the negative control; however, we saw significant cytotoxicity at values above 20 nM (Supplementary Fig. S1). The compounds showed approximately equal CC50 values of 118.77 nM (FL3), 92.18 nM (FL23) and 138.53 nM (sulfonyl amidine 1 m) as calculated from dose response curves (see Supplementary Fig. S2).

To confirm the results of the MTT assay, we cultured Hek293T/17 cells and incubated them with various concentrations of FL3, FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m at 37 °C or mock incubated them with vehicle/DMEM for 1 hr, after which we washed the cells and re‐incubated them with the same concentration of drug for a further 24 hrs. We employed this two‐step incubation to more closely mimic infection protocols as undertaken at later stages. We found approximately 80% apoptosis induction in cells treated with 5% DMSO as a positive control; however, amounts of apoptosis in cells treated with different concentrations (1, 5, 10 and 20 nM) of the compounds under investigation were comparable to that in negative control (mock) cells treated with vehicle/DMEM (Supplementary Fig. S3).

To evaluate potential virucidal activity, we incubated stock CHIKV directly with each compound separately at different concentrations for 1 hr or with vehicle/DMEM, after which we determined virus titers by standard plaque assays on Vero cells. We observed no direct effect of the compounds on the virus (Supplementary Fig. S4). We repeated the experiment using virus/compound mixtures to infect Hek293T/17 cells and found no significant effect on the ability of the virus to infect into Hek293T/17 cells. Moreover, plaque assay analysis of the highest concentration treatments showed no significant effect on virus production (Supplementary Fig. S4). Combined, these results show that the three compounds tested do not possess anti‐CHIKV virucidal activity.

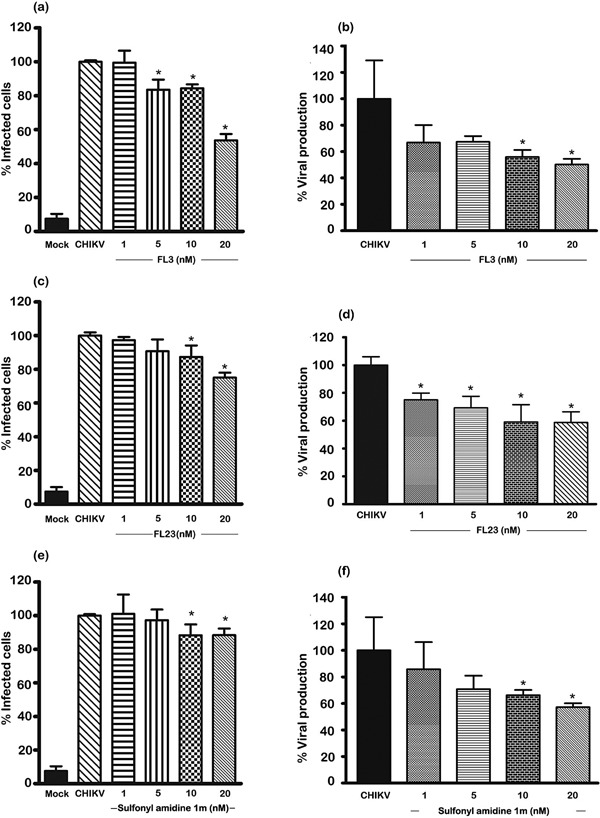

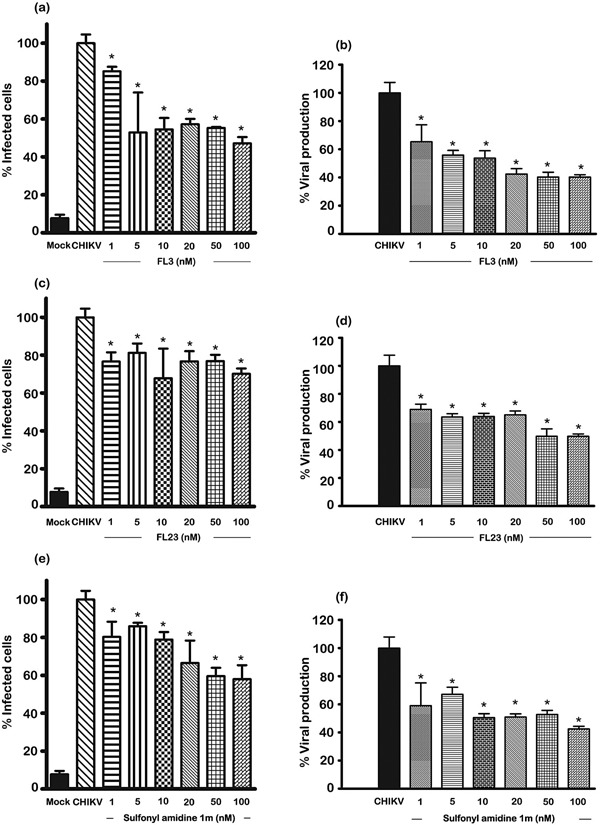

Effect of compounds on CHIKV infection

To determine the effects of the compounds on CHIKV infection, we cultured Hek293T/17 cells and then pre‐incubated them with and without FL3, FL23 or sulfonyl amidine 1 m at various concentrations for 1 hr followed by infection with 10 pfu/cells of CHIKV or mock infected in serum‐free medium without the compounds under investigation. After 2 hr, we removed extracellular virus by washing three times and subsequently incubated the cells in complete medium under standard conditions in the presence of the compounds for 20 hrs, after which we harvested the cells for flow cytometry and collected the supernatant for standard plaque assay. We found a reduction in the percentage of infected cells for all three compounds at concentrations of 10 and 20 nM (Fig. 3a,c,e), whereas FL3 additionally showed a significant reduction in the percentage of cells infected with CHIKV at 5 nM (Fig. 3a). Similarly, we observed a significant reduction in viral production in cells incubated with 10 and 20 nM of the three compounds (Fig. 3b,d,f and Supplementary Fig. S5), whereas FL23 additionally showed a significant effect on virus production at 1 and 5 nM (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. S5). The maximum effect observed was with 20 nM FL3, which reduced both infection and virus production by nearly 50%, the IC50 for this compound was 22.4 nM.

Figure 3.

Effects of various compounds on CHIKV infection of Hek293T/17 cells. Hek293T/17 cells were pre‐incubated with vehicle/DMEM (mock and CHIKV) or pre‐incubated with (a, b) FL3, (c,d) FL23 or (e,f) sulfonyl amidine 1 m for 1 hr before being infected with 10 pfu/cell of CHIKV or being mock infected (Mock). After infection, cells were incubated under standard conditions in the presence or absence of the appropriate drug for 20 hrs before (a, c, e) determination of degree of infection of cells by flow cytometry or (b, d, f) assay of the supernatant for virus titer by standard plaque assay. All experiments were undertaken independently in triplicate with duplicate plaque assays; error bars show SD. *, P < 0.05. Mock, pre‐incubation with vehicle/DMEM and mock (CHIKV) infection; CHIKV (incubation with vehicle/DMEM and standard infection).

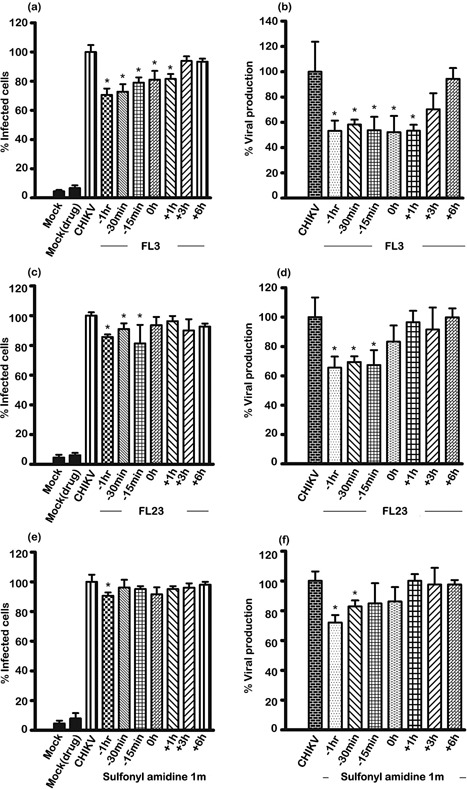

Time course analysis of the effect of compounds on CHIKV infection

To determine whether the compounds were having an effect at the entry step of CHIKV infection, we incubated cells with the highest non‐cytotoxic concentrations of the compounds (20 nM) for increasingly shorter times pre‐infection, or added them only after infection. We analyzed cells and supernatant at 20 hrs post‐infection as in previous experiments.

We found that FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m only had effects on the number of infected cells and the amount of virus production when the cells were pre‐incubated with the compounds (Fig. 4). We saw no effect when we added these two compounds post‐infection (Fig. 4c–f and Supplemental Fig. S6). FL23 showed some effect when the pre‐incubation was as short as 15 minutes pre‐infection, whereas sulfonyl amidine 1 m showed an effect on number of cells infected only with pre‐incubation for 1 hr pre‐infection.

Figure 4.

Time course of effect of flavaglines on CHIKV infection of Hek293T/17 cells. Hek293T/17 cells were mock pre‐incubated with vehicle/DMEM or pre‐incubated with (a, b) FL3, (c,d) FL23 or (e,f) sulfonyl amidine 1 m for the indicated times before being infected with 10 pfu/cell of CHIKV or being mock (Mock) infected, or the compounds were added at the indicated times post‐infection. After infection, cells were incubated under standard conditions in the presence or absence of the drug as appropriate for 20 hrs before (a, c, e) determination of degree of infection of cells by flow cytometry or (b, d, f) the supernatant assayed for virus titer by standard plaque assay. Mock, incubation with vehicle/DMEM and mock infection; Mock (drug), incubation with compound and mock infection; CHIKV, incubation with vehicle/DMEM and standard CHIKV infection. All experiments were undertaken independently in triplicate with duplicate plaque assays; error bars show SD. *, P < 0.05.

FL3 showed both the largest effect and the greatest range of time points that had an effect. Even incubation with FL3 at 1 hr post‐infection had a significant effect on both number of cells infected and amount of virus produced. This may mean that continued inhibition of virus entry was not completely prevented by the washing step and suggests that FL3 may remain associated with PHB for a longer time than either FL23 or sulfonyl amidine 1 m. However, addition of FL3 at 3 hrs post‐infection showed no significant effect.

Effect of pulse treatment of compounds on CHIKV infection

The results of the time course experiment are consistent with the action of the compounds occurring at the attachment/entry step of CHIKV infection. To further verify this, we undertook experiments with a short (15 minutes) pulse pre‐treatment with wash out of the compound before infection. Because the cell treatment was for a short period, it was possible that we could use higher concentrations of the compounds. To verify this, we treated cells for 15 minutes with different concentrations of the compounds (up to 100 nM), after which we washed the cells twice with DMEM before incubating them under standard conditions for 24 hrs and assessing cell viability as undertaken previously. We found no evident loss of cell viability, even at the highest concentration used (100 nM; Supplementary Fig. 7). We therefore repeated the experiment and infected the cells after washing with CHIKV and assayed for degree of infection and virus production at 20 hrs post‐infection as before. We found a significant reduction in both infection and virus production under all conditions tested (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S8). Virus output for both FL3 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m was reduced by nearly 60% by pulse treatment at 100 nM as compared with untreated cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of pulse pre‐treatment of compounds on CHIKV infection of Hek293T/17 cells. Hek293T/17 cells were mock pre‐incubated with vehicle/DMEM or pre‐incubated with (a, b) FL3, (c,d) FL23 or (e,f) sulfonyl amidine 1 m for 15 minutes after which cells were washed twice before being infected with 10 pfu/cell of CHIKV or being mock infected. After infection, cells were incubated under standard conditions for 20 hrs before (a, c, e) determination of degree of infection of cells by flow cytometry or (b, d, f) assay of the supernatant for virus titer by standard plaque assay. All experiments were undertaken independently in triplicate with duplicate plaque assays; error bars show SD. *, P < 0.05. Mock, pre‐incubation with vehicle/DMEM and mock (CHIKV) infection; CHIKV, (incubation with vehicle/DMEM and standard infection).

Effect of compounds on CHIKV receptor binding

Finally, to confirm that the compounds acted by interfering with receptor binding, we repeated the initial colocalization experiment between PHB and CHIKV, this time in the presence or absence of each of the compounds. We found a marked reduction in colocalization between CHIKV and PHB when we incubated the virus with cells in the presence of the compounds at 100 nM, as compared to incubation with no compound (Fig. 6). The high degree of colocalization between CHIKV and PHB (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.85, 95% CI 0.82–0.88) was reduced to a statistically significantly degree in the presence of FL3 (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.22; 95% CI 0.09–0.34; P<0.05) and FL23 (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.63; 95% CI 0.53–0.73; P<0.05) and reduced, although not significantly, in the presence of sulfonyl amidine 1 m (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.72; 95% CI 0.34–1.09) These results confirm that the ligands interfere with the receptor binding of CHIKV.

Figure 6.

Colocalization of CHIKV E2 protein with PHB in the presence and absence of test compounds. Hek293T/17 cells were grown on glass slides and incubated with CHIKV or mock incubated in the presence and absence of test compounds at 100 nM and examined for cell surface colocalization of PHB (red) and CHIKV E2 protein (green). Fluorescent signals were observed using an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal microscope. Scale bar for magnification is shown. Representative, non‐contrast adjusted, unmerged and merged images are shown.

DISCUSSION

Prohibitin is located in a number of cell compartments, primarily the mitochondria; cell surface expression has also been demonstrated in a number of studies 20, 26, 41, 42, 43, 44. PHB has been shown to interact with a number of different pathogens or pathogen proteins including CHIKV 20, dengue 27, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 45, HIV 46 and foot‐and‐mouth disease virus 47.

Prohibitins have been shown to be specific targets for flavaglines 36. Flavaglines are a family of natural products found in plants of the genus Aglaia, family Meliaceae (mahogany), of which the first identified molecule was rocaglamide 48. Rocaglamide was first identified based on its potent anti‐leukemic activity; since then both natural and synthetic flavaglines have been shown to have potent anti‐cancer properties, often in the low nanomolar range 34, 35. Recent studies have suggested that flavaglines, including rocaglamide and silvestrol, are promising candidates for the treatment of leukemia 49. Studies have shown that the anti‐cancer action of flavaglines derives, at least in part, from a specific interaction between PHB and flavaglines 36. This study was undertaken to determine whether the interaction between flavaglines and PHB was sufficient to disrupt the interaction between PHB and CHIKV. All of our results are consistent with the compounds acting at the entry stage, possibly by physically interfering with the binding of CHIKV to the PHB receptor. The maximum inhibition observed was approximately 50% of viral entry (seen with pulse treatment of cells with FL3), a degree of inhibition consistent with that seen in previous antibody inhibition experiments 20. The compounds tested showed little effect when added post‐entry; while this may suggest that flavaglines have only limited potential utility as prophylactic agents, because natural infections are not synchronous, administration during the course of the disease could have therapeutic effects by preventing new cells from becoming infected. The fact that both antibody inhibition experiments 20 and the compounds tested here showed a maximum effect on entry of about 50% may indicate that CHIKV uses multiple receptor protein to enter susceptible cells.

The compounds tested showed significant cytotoxicity to Hek293T/17 cells under conditions of continuous culture, consistent with the compounds known anti‐cancer activities 34, 35. However, no cytotoxicity was observed after exposure to dramatically higher doses when the compounds were administered as short (15 minute) pulses. Importantly, these compounds show no toxicity to normal cells and do not display any evidence of toxicity in vivo 33, suggesting that these compounds, or indeed other ligands of PHB, could form the basis of a prophylactic or therapeutic regime in CHIKV outbreaks.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site.

Figure S1: Determination of cell viability. Hek293T/17 cells were incubated with different concentrations of (a) DMSO, (b) FL3, (c) FL23 or (d) sulfonyl amidine 1 m for 24 hours before determination of cell viability using the MTT assay. Data is derived from eight replicates; error bars show SD. *, P < 0.05; negative, vehicle/DMEM, positive, 5% DMSO.

Figure S2: Dose response curves generated by the ED50plus (v1.0) software used for CC50 calculations.

Figure S3: Analysis of apoptosis in response to treatment with flavaglines. Hek293T/17 cells were incubated with different concentrations of (a) FL3, (b) FL23 or (c) sulfonyl amidine 1 m for 24 hours before determination of the amount of apoptosis by annexin V/propidium iodide staining and analysis by flow cytometry. Experiments were undertaken independently in triplicate; error bars show SD. Mock, vehicle/DMEM.

Figure S4: Analysis of virucidal activity of flavaglines. Stock CHIKV was incubated for 1 hr in the presence or absence of various concentrations of FL3, FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m after which the virus was either (a) directly assayed by standard plaque assay or (b) used to infect Hek293T/17, with the percentage infection being determined at 20 hours by flow cytometry. (c) Virus titers in the supernatants from 20 nM treatments in (b) were assayed by standard plaque assay. Experiments were undertaken independently in triplicate with duplicate plaque assays; error bars show SD. Mock, mock virus incubated with vehicle/DMEM; CHIKV, CHIKV incubated with vehicle/DMEM.

Figure S5: Virus production data from Figure 3 plotted as pfu/mL.

Figure S6: Virus production data from Figure 4 plotted as pfu/mL.

Figure S7: Determination of cell viability after pulse treatment. Hek293T/17 cells were incubated with different concentrations of (a) FL3, (b) FL23 or (c) sulfonyl amidine 1 m for 15 minutes, after which cells were washed and incubated under standard conditions for a further 24 hrs before determination of cell viability using the MTT assay. Data is derived from eight replicates. Negative (vehicle/DMEM) and positive (5% DMSO) controls were run in parallel. Error bar show SD. *, P < 0.05.

Figure S8: Virus production data from Figure 5 plotted as pfu/mL.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from Mahidol University and the Office of the Higher Education Commission under the National Research Universities Initiative, The Thailand Research Fund (IRG5780009) and Mahidol University. P.W. was supported by a Thailand Graduate Institute of Science and Technology (TGIST) PhD scholarship. We also thank AAREC Filia Research (C.B.) and MNESR (F.T.) for fellowships.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Burt F.J., Rolph M.S., Rulli N.E., Mahalingam S., Heise M.T. ( 2012) Chikungunya: a re‐emerging virus. Lancet 379: 662–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwartz O., Albert M.L. ( 2010) Biology and pathogenesis of chikungunya virus. Nat Rev Microbiol 8: 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Voss J.E., Vaney M.C., Duquerroy S., Vonrhein C., Girard‐Blanc C., Crublet E., Thompson A., Bricogne G., Rey F.A. ( 2010) Glycoprotein organization of Chikungunya virus particles revealed by X‐ray crystallography. Nature 468: 709–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Robinson M.C. ( 1955) An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province. Tanganyika Territory, in1952–53 I Clinical features Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 49: 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ross R.W. ( 1956) The Newala epidemic. III. The virus: isolation, pathogenic properties and relationship to the epidemic. J Hyg (Lond) 54: 177–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Halstead S.B. ( 1966) Mosquito‐borne haemorrhagic fevers of South and South‐East Asia. Bull World Health Organ 35: 3–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sergon K., Njuguna C., Kalani R., Ofula V., Onyango C., Konongoi L.S., Bedno S., Burke H., Dumilla A.M., Konde J., Njenga M.K., Sang R., Breiman R.F. ( 2008) Seroprevalence of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection on Lamu Island, Kenya, October 2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg 78: 333–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sergon K., Yahaya A.A., Brown J., Bedja S.A., Mlindasse M., Agata N., Allaranger Y., Ball M.D., Powers A.M., Ofula V., Onyango C., Konongoi L.S., Sang R., Njenga M.K., Breiman R.F. ( 2007) Seroprevalence of Chikungunya virus infection on Grande Comore Island, union of the Comoros, 2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg 76: 1189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Josseran L., Paquet C., Zehgnoun A., Caillere N., Le Tertre A., Solet J.L., Ledrans M. ( 2006) Chikungunya disease outbreak, Reunion Island. Emerg Infect Dis 12: 1994–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gerardin P., Guernier V., Perrau J., Fianu A., Le Roux K., Grivard P., Michault A., De Lamballerie X., Flahault A., Favier F. ( 2008) Estimating Chikungunya prevalence in La Reunion Island outbreak by serosurveys: two methods for two critical times of the epidemic. BMC Infect Dis 8: 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Renault P., Solet J.L., Sissoko D., Balleydier E., Larrieu S., Filleul L., Lassalle C., Thiria J., Rachou E., De Valk H., Ilef D., Ledrans M., Quatresous I., Quenel P., Pierre V. ( 2007) A major epidemic of chikungunya virus infection on Reunion Island, France, 2005– 2006. Am J Trop Med Hyg 77: 727–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ng L.C., Hapuarachchi H.C. ( 2010) Tracing the path of Chikungunya virus—evolution and adaptation. Infect Genet Evol 10: 876–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Powers A.M. ( 2010) Chikungunya. Clin Lab Med 30: 209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pulmanausahakul R., Roytrakul S., Auewarakul P., Smith D.R. ( 2011) Chikungunya in Southeast Asia: understanding the emergence and finding solutions. Int J Infect Dis 15: 671–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tomasello D., Schlagenhauf P. ( 2013) Chikungunya and dengue autochthonous cases in Europe 2007–2012. Travel Med Infect Dis 5: 274–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sourisseau M., Schilte C., Casartelli N., Trouillet C., Guivel‐Benhassine F., Rudnicka D., Sol‐Foulon N., Le Roux K., Prevost M.C., Fsihi H., Frenkiel M.P., Blanchet F., Afonso P.V., Ceccaldi P.E., Ozden S., Gessain A., Schuffenecker I., Verhasselt B., Zamborlini A., Saib A., Rey F.A., Arenzana‐Seisdedos F., Despres P., Michault A., Albert M.L., Schwartz O. ( 2007) Characterization of reemerging chikungunya virus. PLoS Pathog 3: e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wikan N., Sakoonwatanyoo P., Ubol S., Yoksan S., Smith D.R. ( 2012) Chikungunya virus infection of cell lines: analysis of the East, Central and South African lineage. PLoS ONE 7: e31102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Her Z., Malleret B., Chan M., Ong E.K., Wong S.C., Kwek D.J., Tolou H., Lin R.T., Tambyah P.A., Renia L., Ng L.F. ( 2010) Active infection of human blood monocytes by Chikungunya virus triggers an innate immune response. J Immunol 184: 5903–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bernard E., Solignat M., Gay B., Chazal N., Higgs S., Devaux C., Briant L. ( 2010) Endocytosis of chikungunya virus into mammalian cells: role of clathrin and early endosomal compartments. PLoS ONE 5: e11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wintachai P., Wikan N., Kuadkitkan A., Jaimipuk T., Ubol S., Pulmanausahakul R., Auewarakul P., Kasinrerk W., Weng W.Y., Panyasrivanit M., Paemanee A., Kittisenachai S., Roytrakul S., Smith D.R. ( 2012) Identification of prohibitin as a Chikungunya virus receptor protein. J Med Virol 84: 1757–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thuaud F., Bernard Y., Turkeri G., Dirr R., Aubert G., Cresteil T., Baguet A., Tomasetto C., Svitkin Y., Sonenberg N., Nebigil C.G., Desaubry L. ( 2009) Synthetic analogue of rocaglaol displays a potent and selective cytotoxicity in cancer cells: involvement of apoptosis inducing factor and caspase‐12. J Med Chem 52: 5176–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ikonen E., Fiedler K., Parton R.G., Simons K. ( 1995) Prohibitin, an antiproliferative protein, is localized to mitochondria. FEBS Lett 358: 273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Merkwirth C., Langer T. ( 2009) Prohibitin function within mitochondria: essential roles for cell proliferation and cristae morphogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793: 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nijtmans L.G., De Jong L., Artal Sanz, Coates M., Berden P.J., Back J.A., Muijsers J.W., Van Der Spek A.O., Grivell H. ( 2000) Prohibitins act as a membrane‐bound chaperone for the stabilization of mitochondrial proteins. Embo J 19: 2444–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thuaud F., Ribeiro N., Nebigil C.G., Desaubry L. ( 2013) Prohibitin ligands in cell death and survival: mode of action and therapeutic potential. Chem Biol 20: 316–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharma A., Qadri A. ( 2004) Vi polysaccharide of Salmonella typhi targets the prohibitin family of molecules in intestinal epithelial cells and suppresses early inflammatory responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 17492–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuadkitkan A., Wikan N., Fongsaran C., Smith D.R. ( 2010) Identification and characterization of prohibitin as a receptor protein mediating DENV‐2 entry into insect cells. Virology 406: 149–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuadkitkan A., Smith D.R., Berry C. ( 2012) Investigation of the Cry4B‐prohibitin interaction in Aedes aegypti cells. Curr Microbiol 65: 446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akahata W., Yang Z.Y., Andersen H., Sun S., Holdaway H.A., Kong W.P., Lewis M.G., Higgs S., Rossmann M.G., Rao S., Nabel G.J. ( 2010) A virus‐like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat Med 16: 334–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Edelman R., Tacket C.O., Wasserman S.S., Bodison S.A., Perry J.G., Mangiafico J.A. ( 2000) Phase II safety and immunogenicity study of live chikungunya virus vaccine TSI‐GSD‐218. Am J Trop Med Hyg 62: 681–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang E., Volkova E., Adams A.P., Forrester N., Xiao S.Y., Frolov I., Weaver S.C. ( 2008) Chimeric alphavirus vaccine candidates for chikungunya. Vaccine 26: 5030–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weaver S.C., Osorio J.E., Livengood J.A., Chen R., Stinchcomb D.T. ( 2012) Chikungunya virus and prospects for a vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines 11: 1087–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bernard Y., Ribeiro N., Thuaud F., Turkeri G., Dirr R., Boulberdaa M., Nebigil C.G., Desaubry L. ( 2011) Flavaglines alleviate doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: implication of Hsp27. PLoS ONE 6: e25302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ribeiro N., Thuaud F., Bernard Y., Gaiddon C., Cresteil T., Hild A., Hirsch E.C., Michel P.P., Nebigil C.G., Desaubry L. ( 2012) Flavaglines as potent anticancer and cytoprotective agents. J Med Chem 55: 10064–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ribeiro N., Thuaud F., Nebigil C., Desaubry L. ( 2012) Recent advances in the biology and chemistry of the flavaglines. Bioorg Med Chem 20: 1857–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Polier G., Neumann J., Thuaud F., Ribeiro N., Gelhaus C., Schmidt H., Giaisi M., Kohler R., Muller W.W., Proksch P., Leippe M., Janssen O., Desaubry L., Krammer P.H., Li‐Weber M. ( 2012) The natural anticancer compounds rocaglamides inhibit the Raf‐MEK‐ERK pathway by targeting prohibitin 1 and 2. Chem Biol 19: 1093–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang S.Y., Bae S.J., Lee M.Y., Baek S.H., Chang S., Kim S.H. ( 2011) Chemical affinity matrix‐based identification of prohibitin as a binding protein to anti‐resorptive sulfonyl amidine compounds. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 21: 727–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee M.Y., Kim M.H., Kim J., Kim S.H., Kim B.T., Jeong I.H., Chang S., Kim S.H., Chang S.Y. ( 2010) Synthesis and SAR of sulfonyl‐ and phosphoryl amidine compounds as anti‐resorptive agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 20: 541–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fongsaran C., Jirakanwisal K., Kuadkitkan A., Wikan N., Wintachai P., Thepparit C., Ubol S., Phaonakrop N., Roytrakul S., Smith D.R. ( 2014) Involvement of ATP synthase beta subunit in chikungunya virus entry into insect cells. Arch Virol 159: 3353–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Panyasrivanit M., Khakpoor A., Wikan N., Smith D.R. ( 2009) Co‐localization of constituents of the dengue virus translation and replication machinery with amphisomes. J Gen Virol 90: 448–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kolonin M.G., Saha P.K., Chan L., Pasqualini R., Arap W. ( 2004) Reversal of obesity by targeted ablation of adipose tissue. Nat Med 10: 625–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patel N., Chatterjee S.K., Vrbanac V., Chung I., Mu C.J., Olsen R.R., Waghorne C., Zetter B.R. ( 2010) Rescue of paclitaxel sensitivity by repression of Prohibitin1 in drug‐resistant cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 2503–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yurugi H., Tanida S., Ishida A., Akita K., Toda M., Inoue M., Nakada H. ( 2012) Expression of prohibitins on the surface of activated T cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 420: 275–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang Y., Wang Y., Xiang Y., Lee W., Zhang Y. ( 2012) Prohibitins are involved in protease‐activated receptor 1‐mediated platelet aggregation. J Thromb Haemost 10: 411–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cornillez‐Ty C.T., Liao L., Yates J.R., 3rd , Kuhn P., Buchmeier M.J. ( 2009) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein 2 interacts with a host protein complex involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and intracellular signaling. J Virol 83: 10314–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Emerson V., Holtkotte D., Pfeiffer T., Wang I.H., Schnolzer M., Kempf T., Bosch V. ( 2010) Identification of the cellular prohibitin 1/prohibitin 2 heterodimer as an interaction partner of the C‐terminal cytoplasmic domain of the HIV‐1 glycoprotein. J Virol 84: 1355–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chiu C.F., Peng J.M., Hung S.W., Liang C.M., Liang S.M. ( 2012) Recombinant viral capsid protein VP1 suppresses migration and invasion of human cervical cancer by modulating phosphorylated prohibitin in lipid rafts. Cancer Lett 320: 205–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lu King, Chiang M., Ling C‐C., Fujita H‐C., Ochiai E., Mcphail M. ( 1982) X‐ray crystal structure of rocaglamide, a novel antileulemic 1H‐cyclopenta[b]benzofuran from Aglaia elliptifolia . J Chem Soc Chem Commun 20: 1150–1. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Callahan K.P., Minhajuddin M., Corbett C., Lagadinou E.D., Rossi R.M., Grose V., Balys M.M., Pan L., Jacob S., Frontier A., Grever M.R., Lucas D.M., Kinghorn A.D., Liesveld J.L., Becker M.W., Jordan C.T. ( 2014) Flavaglines target primitive leukemia cells and enhance anti‐leukemia drug activity. Leukemia 28: 1960–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site.

Figure S1: Determination of cell viability. Hek293T/17 cells were incubated with different concentrations of (a) DMSO, (b) FL3, (c) FL23 or (d) sulfonyl amidine 1 m for 24 hours before determination of cell viability using the MTT assay. Data is derived from eight replicates; error bars show SD. *, P < 0.05; negative, vehicle/DMEM, positive, 5% DMSO.

Figure S2: Dose response curves generated by the ED50plus (v1.0) software used for CC50 calculations.

Figure S3: Analysis of apoptosis in response to treatment with flavaglines. Hek293T/17 cells were incubated with different concentrations of (a) FL3, (b) FL23 or (c) sulfonyl amidine 1 m for 24 hours before determination of the amount of apoptosis by annexin V/propidium iodide staining and analysis by flow cytometry. Experiments were undertaken independently in triplicate; error bars show SD. Mock, vehicle/DMEM.

Figure S4: Analysis of virucidal activity of flavaglines. Stock CHIKV was incubated for 1 hr in the presence or absence of various concentrations of FL3, FL23 and sulfonyl amidine 1 m after which the virus was either (a) directly assayed by standard plaque assay or (b) used to infect Hek293T/17, with the percentage infection being determined at 20 hours by flow cytometry. (c) Virus titers in the supernatants from 20 nM treatments in (b) were assayed by standard plaque assay. Experiments were undertaken independently in triplicate with duplicate plaque assays; error bars show SD. Mock, mock virus incubated with vehicle/DMEM; CHIKV, CHIKV incubated with vehicle/DMEM.

Figure S5: Virus production data from Figure 3 plotted as pfu/mL.

Figure S6: Virus production data from Figure 4 plotted as pfu/mL.

Figure S7: Determination of cell viability after pulse treatment. Hek293T/17 cells were incubated with different concentrations of (a) FL3, (b) FL23 or (c) sulfonyl amidine 1 m for 15 minutes, after which cells were washed and incubated under standard conditions for a further 24 hrs before determination of cell viability using the MTT assay. Data is derived from eight replicates. Negative (vehicle/DMEM) and positive (5% DMSO) controls were run in parallel. Error bar show SD. *, P < 0.05.

Figure S8: Virus production data from Figure 5 plotted as pfu/mL.