Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects over 15% of the adults in the United States. Pregnant women with CKD present an additional challenge in that they are at increased risk for adverse events such as preterm birth. Exposure to environmental toxicants, such as methylmercury, may exacerbate maternal disease and increase the risk of adverse fetal outcomes. We hypothesized that fetuses of mothers with CKD are more susceptible to accumulation of methylmercury than fetuses of healthy mothers. The current data show that when mothers are in a state of renal insufficiency, uptake of mercury in fetal kidneys is enhanced significantly. Accumulation of Hg in fetal kidneys may be related to the flow of amniotic fluid, maternal handling of Hg, and/or underdeveloped mechanisms for cellular export and urinary excretion. The results of this study indicate that renal insufficiency in mothers leads to significant alterations in the way toxicants such as mercury are handled by maternal and fetal organs.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, mercury, heavy metals, kidney

Introduction

According to the CDC, more than 15% of American adults, totaling more than 37 million people, are affected by chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1]. This disease, which is most often caused by diabetes and hypertension, is characterized by a progressive and permanent loss of functioning nephrons. Importantly, only 50% of individuals with significantly reduced renal function are aware of their disease [1]. Undiagnosed individuals may continue to engage in activities or be exposed to chemicals/toxicants that may enhance the progression of the disease.

Pregnancy is often not recommended for patients with CKD since women with CKD are less able to make the renal adaptations necessary to sustain a healthy pregnancy [2]. However, it is not uncommon that women with CKD become pregnant, particularly if they are unaware of their disease. In some cases, pregnancy may lead to the discovery of a CKD diagnosis. Pregnancy in CKD patients can create additional challenges for both the mother and fetus, regardless of the stage of CKD. CKD patients who become pregnant are at higher risk for preeclampsia, preterm delivery, perinatal death, incidence of Caesarean sections, and enhanced progression of their own disease [2–4].

Exposure to environmental toxicants presents another challenge to pregnant women, particularly those with CKD. Exposure of CKD patients to environmental and/or occupational toxicants appears to enhance the progression of the disease [5]. Patients who are pregnant may be particularly susceptible to the effects of environmental toxicants in that exposure to these toxicants could worsen outcomes for both mothers and infants. Even exposure to environmental toxicants prior to CKD or pregnancy may contribute to adverse outcomes in patients [6, 7].

An environmental toxicant of particular concern is mercury. Humans are exposed to various forms of mercury primarily through occupational and/or dietary routes. Interestingly, recent studies have found detectable levels of mercury in thousands of children and adults in the United States, indicating that mercury exposure and possible intoxication remains a significant health concern [8–10]. Exposure to various forms of mercury through dietary sources, dental amalgams, and medicinal therapies has been shown to have significant toxicological ramifications, including injury to the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, neurological, hepatobiliary, and renal systems [11]. In addition, exposure to organic forms of mercury (e.g., methylmercury) may not only impair reproductive function, but it also may lead to detrimental consequences in the exposed fetus [12]. Interestingly, the concentration of methylmercury has been found to be twofold greater in cord blood than in maternal blood [13, 14], suggesting that fetal exposure to mercury may be greater than maternal exposure.

Exposure of humans to mercury has been shown to reduce glomerular filtration rate and enhance the progression of disease in CKD patients [5, 15, 16]. In addition, it is well-established that mercury is capable of crossing the placenta and accumulating in fetal organs and tissues [17–19]. Given that CKD reduces filtration and excretion of drugs and xenobiotics [20], one would expect that mercury excretion would be decreased in CKD patients, which would lead consequently to retention of mercury and increase the risk of mercury-induced injury. Therefore, the current study was designed to test the hypothesis that fetuses of mothers with CKD would be more susceptible to accumulation of mercury than fetuses of healthy mothers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Manufacture of radioactive methylmercury (CH3[203Hg+])

The manufacture of radioactive mercury ([203Hg2+]) has been described previously. Briefly, three milligrams of enriched mercuric oxide (202Hg) were sealed in quartz tubing and irradiated by neutron activation for four weeks at the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR). After irradiation was complete, the mercuric oxide was dissolved in 1 N HCl. The radioactivity of the solution was determined using an ion chamber. The specific activity of [203Hg2+] was approximately 8 mCi/mg.

A previously published protocol [21], which was adapted from Rouleau and Block [22], was used to generate CH3[203Hg+]. Briefly, 2 mCi of [203Hg2+] (1.25 μmol) were added to 2 mL of 1.55 mM methylcobalamin (3.1 mm), which served as the donor of methyl groups, and sodium acetate (2 M in acetic acid). Potassium chloride (30% in 4% hydrochloric acid) was added to the solution following a 24-h incubation. Five washes of dichloromethane (DCM) were performed to extract CH3[203Hg+]. Nitrogen gas was bubbled into the solution to evaporate the DCM and remaining CH3[203Hg+] was collected. Calculations were performed to determine the specific activity which was approximately 5 mCi/mg. Thin layer chromatography has previously confirmed the purity of the extracted CH3[203Hg+] [22].

Radioactive methylmercury (CH3[203Hg+]) was used in the current study as a reliable tracer for assessing in vivo disposition and accumulation of mercuric ions in organs. Since it emits gamma radiation, the amount of CH3[203Hg+] in organs and tissues can be determined by counting the entire, intact organ whereas use of other radioisotopes could require additional processing and solubilization of samples. The amount of radioactivity that each animal receives is minimal and has not been shown to induce organ or cell injury.

2.2. Animals

Male and female Wistar rats were obtained from our on-site breeding colony. Animals were provided water ad libitum and a commercial laboratory diet (Tekland 6% rat diet, Envigo) throughout all aspects of experimentation. The Mercer University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) reviewed and approved the animal protocol for the current study. Animals were handled in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted by the National Institutes of Health.

2.3. 75% Nephrectomy

Seventy-five % nephrectomy is a reliable model of late-stage renal disease wherein alterations in solute and fluid homeostasis are observed. Female Wistar rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 70 mg/kg ketamine and 6 mg/kg xylazine. A midline incision was made through the skin and musculature of the abdomen and the right and left kidneys of each animal were isolated from the perinephric fascia and fat. For the groups that underwent 75% nephrectomy, the right renal artery and vein and right ureter were ligated with a single sterile 1–0 silk suture. The right kidney was excised distal to the ligature. Subsequently, the left kidney was exteriorized from the body through the mid-line incision and placed in a Lucite cup to expose the posterior surface. Using a dissecting microscope, a sterile 4–0 silk suture was threaded between the renal vein and the posterior branch of renal artery and tied tightly. Successful ligation was confirmed by renal fibrosis and scaring, which were visible at the time of euthanasia. The muscles were approximated using 4–0 silk suture and the skin was closed using 9-mm wound clips. Sham rats were treated similarly, except that their right kidney was not excised and the left renal artery was not ligated.

2.4. Mating of animals and determination of pregnancy

Nephrectomized (NPX) and Sham female rats, weighing 275–300 g, were mated with normal male Wistar rats. Rats were mated approximately 4 weeks after surgery. After mating, vaginal mucus was examined for sperm every 24 hours. Briefly, vaginal mucus was obtained using a cotton-tipped applicator and smeared onto a glass slide. A drop of nuclear fast red stain was added and the slide was cover-slipped and examined under a microscope. The presence of sperm was considered to be confirmatory for pregnancy. The day sperm was detected was considered to be gestational day (GD) 1.

2.5. Exposure of animals to methylmercury

Pregnant NPX and Sham rats were exposed orally to methylmercury on GD 7, GD 13, and GD19. Rats were exposed on GD 7 to facilitate delivery of mercuric ions to the brain at the beginning of neurogenesis. Rats were exposed on GD 19 to allow for a 24-hour period prior to euthanasia on GD 20. GD 13 was chosen as a halfway point between the first and last exposures. At the time of gavage, each animal was anesthetized with 2–5% isoflurane and an 18-gauge gavage needle was used to deliver 2.0 mg • kg−1 • 5 mL−1 methylmercury chloride (1.593 μmol • mL−1) containing 1 μCi CH3[203Hg+]. This dose has been used in previously published studies and is considered to be non-nephrotoxic in adult animals [23]. Subsequently, all animals were placed in individual plastic metabolic cages. Rats were euthanized on GD 20.

2.6. Collection of amniotic fluid, placentas, and fetuses

At the time of euthanasia, rats were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with ketamine (70 mg/kg) and xylazine (30 mg/kg). Each fetus, placenta, and the associated amniotic fluid were extracted individually. Each placenta was weighed and then placed in a polystyrene tube for estimation of mercury (Hg) content. A piece of Whatman paper was used to collected amniotic fluid and was placed in a polystyrene tube for estimation of Hg content. Each fetus was weighed, decapitated, and then placed in 5 mL of 80% ethanol (w/v) in a glass scintillation vial for determination of total Hg content. After counting the entire fetus, the brain, kidneys, and liver of each fetus were removed, weighed, and placed in individual polystyrene tubes for estimation of Hg content. The mean body and organ weights are listed in Table 1. A Wallac Wizard 3 automatic gamma counter was used to determine the content of Hg in each sample. Standard computational methods were used to estimate the amount of Hg in each sample.

Table 1.

Body and organ weights for fetuses and dams.

| Fetal body and organ weights | |||||||

| Body weight | Fetal Total Renal Mass | Fetal Liver | Fetal Brain | ||||

| Sham | 2.22 ± 0.15 | 0.012 ± 0.0007 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | |||

| NPX | 1.87 ± 0.11* | 0.010 ± 0.0006* | 0.14 ± 0.02* | 0.14 ± 0.001* | |||

| Dam body and organ weights | |||||||

| Body weight | Total Renal Mass | Left Kidney | Liver | Brain | Placenta | Uterus | |

| Sham | 486.49 ± 26.12 | 2.18 ± 0.14 | 1.28 ± 0.09 | 14.79 ± 0.84 | 1.80 ± 0.06 | 0.78 ± 0.02 | 6.47 ± 0.39 |

| NPX | 331.73 ± 24.74* | 1.67 ± 0.07* | 0.69 ± 0.04* | 15.38 ± 0.84 | 1.78 ± 0.14 | 0.76 ± 0.01 | 5.55 ± 0.83 |

statistically different (p < 0.05) from corresponding value for Sham rats.

2.7. Collection of tissues and organs

Once the uterus, placentas, and fetuses were removed, a 3-mL sample of blood was obtained from the inferior vena cava. A 1-mL sample was transferred to a polystyrene tube for estimation of Hg content. In order to separate plasma from the cellular contents of blood, 0.5 mL of blood was placed in a blood separation tube and centrifuged for at 21,000 g for 90 sec. Total blood volume was approximated to be 6% of body weight [24]. Serum creatinine was assessed using the QuantiChrome creatinine assay (BioAssay).

From NPX rats, the remnant kidney was removed, weighed, and cut in half along the mid-transverse plane. A thin transverse section was placed in fixative (40% formaldehyde, 50% glutaraldehyde in 96.7 mM NaH2PO4 and 67.5 mM NaOH) for histological analyses. A second transverse section was used to obtain samples of cortex, outer stripe of outer medulla (OSOM), inner stripe of outer medulla (ISOM), and inner medulla. The remaining renal tissue was weighed and placed in a separate polystyrene tube for estimation of Hg content. In Sham rats, the right kidney was removed, weighed, cut in half, and was placed in fixative for future histological analyses. The left kidney was also weighed and cut in half. A thin transverse section was used to obtain samples of the cortex, OSOM, ISOM, and inner medulla. The remaining renal tissue was weighed and each half was placed in a polystyrene tube for estimation of Hg content. The liver was excised, weighed, and a 1-g section was placed in a polystyrene tube for determination of Hg content. The mean body and organ weights are listed in Table 1.

Urine and feces were collected on GD8, GD14, and GD20. A 1-mL sample of urine was weighed and placed in a polystyrene tube for estimation of Hg content. The total amount of feces excreted by each animal was counted to determine the total fecal content of Hg. A Wallac Wizard 3 automatic gamma counter (PerkinElmer) was used to determine the content of Hg in each sample.

2.8. Histological analyses of fetal kidneys

After fixation, maternal and fetal kidneys were washed twice with normal saline and then placed in 70% ethanol. A Tissue-Tek VIP processor was used to process tissues using the following sequence: 95% ethanol for 30 minutes (twice); 100% ethanol for 30 minutes (twice); 100% xylene (twice). Subsequently, tissue was embedded in POLY/Fin paraffin (ThermoFisher). A Leitz 1512 microtome was used to cut 5-μm sections, which were then mounted on glass slides. Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) were used to stain each section and were then viewed using an Olympus IX70 microscope. A Jenoptix Progress C12 digital camera was used to capture images. Glomerular and tubular diameters were measured using a calibrated measurement tool in the Jenoptix Capture software. The following scale was used to quantify the presence of inflammatory cells in glomeruli of fetal kidneys: 1 – no obvious lymphocytes; 2 – 1 lymphocyte per glomerulus in field; 3 – 2 lymphocytes per glomerulus in field; 4 – 3 lymphocytes per glomerulus in field.

2.9. Data calculation and statistical analyses

The amount of Hg in each sample was calculated using standard computational methods. Six “standards” containing 0.1 mL each of the gavage solution (159.3 nmol/0.1 mL methylmercury) were counted in the gamma counter to obtain counts per minute (cpm). A mean was calculated and using the known concentration of the standard, cpm/nmol was calculated according to the following formula: standard cpm in 0.01 mL ÷ nmol in 0.1 mL. The following formula was used to calculate nmol in each tissue sample: sample cpm ÷ cpm/nmol. The % of administered methylmercury in each sample was calculated as nmol ÷ injected nmol x 100. The % administered dose/g was calculated as % administered dose ÷ tissue weight (g).

Data represent mean ± standard error. For data from dams, Sham n = 8 and NPX n = 5. For data from fetuses, placentas, and amniotic fluid, Sham n = 125 and NPX n = 61. The average number of fetuses from Sham dams was 15.75 while the average number of fetuses from NPX dams was 12.6. This difference was statistically significant. The % administered dose of Hg was calculated for organs in each dam. Subsequently, a mean of means was calculated to include all fetuses, placentas, samples of amniotic fluid from each dam within each group. For histopathological scores in fetal kidneys, 10 glomeruli (n = 10) were scored from randomly selected fetal kidneys from each dam. A mean score was obtained for each dam and then a mean of means was obtained for each group (Sham vs. NPX). For measurement of glomerular areas, 15 randomly selected glomeruli (n = 15) centered in the plane of section were measured from each maternal kidney. A mean glomerular area was obtained for each dam and then a mean of means was obtained for each group (Sham vs NPX). Proximal tubular diameter was measured in a similar way (n = 15). Means were compared using a t-test. Statistical significance was represented by a p-value of <0.05, which was chosen a priori.

3. Results

3.1. Fetal burden of Hg

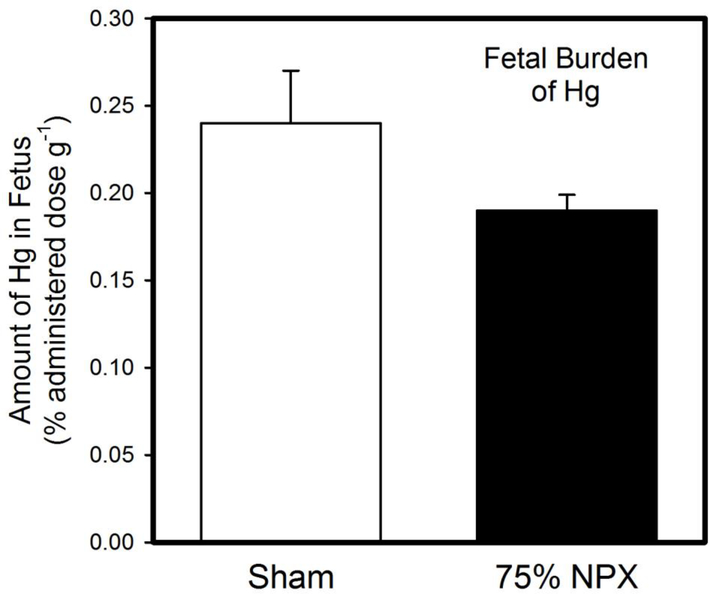

The amount of Hg (% administered dose g−1) in each fetus is shown in Figure 1. There was no significant difference in Hg content between fetuses of Sham rats and those of NPX rats.

Figure 1. Fetal Burden of Hg.

When pregnant Sham or 75% nephrectomized (NPX) rats were exposed to three doses of 2.0 mg/kg methylmercury, the burden of Hg in fetuses from Sham dams was not significantly different from that in fetuses from corresponding NPX dams. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Sham: n = 8 dams; 125 fetuses. NPX: n = 5 dams; 61 fetuses.

The amount of Hg (% administered dose g−1) in the total renal mass of each fetus is shown in Figure 2A. The amount of Hg in the total renal mass of fetuses from NPX dams was significantly greater than that of fetuses from Sham dams. In contrast, the amount of Hg in livers (Figure 2B) and brains (Figure 2C) of fetuses from Sham dams was not significantly different from that in livers and brains, respectively, of fetuses from NPX dams (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Burden of Hg in Fetal Organs.

When pregnant Sham or 75% nephrectomized (NPX) rats were exposed to three doses of 2.0 mg/kg methylmercury, the amount of Hg in the total renal mass (A) of fetuses from NPX dams was significantly greater than that of fetuses from Sham dams. In contrast, the burden of Hg in liver (B) and brain (C) of fetuses from Sham dams was not significantly different from that of fetuses from NPX dams. *, significantly different (p < 0.05) from the mean of the corresponding group of Sham rats. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Sham: n = 8 dams; 125 fetuses. NPX: n = 5 dams; 61 fetuses.

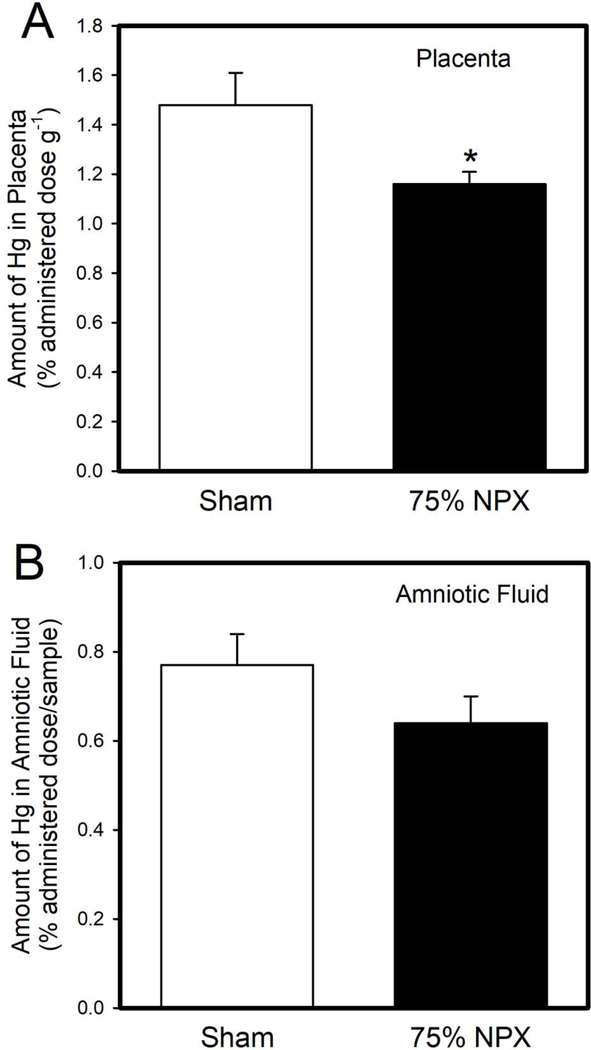

3.2. Amount of Hg in Placenta and Amniotic Fluid

The amount of Hg (% administered dose g−1) in placentas of NPX dams was significantly lower than that in placentas of Sham dams (Figure 3A). In contrast, the amount of Hg in amniotic fluid (% administered dose/sample) from NPX dams was not significantly different than that in amniotic fluid from Sham dams (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Burden of Hg in Placenta and Amniotic Fluid.

The amount of Hg in placentas (A) of NPX dams exposed to 2.0 mg/kg methylmercury was significantly lower than that in placentas of corresponding Sham dams. In contrast, the amount of Hg in amniotic fluid (B) from Sham dams was not significantly different from that in amniotic fluid in NPX dams. *, significantly different (p < 0.05) from the mean of the corresponding group of Sham rats. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Sham: n = 8 dams; 125 fetuses. NPX: n = 5 dams; 61 fetuses.

3.3. Histological Analyses of Fetal and Maternal Kidneys

Sections of fetal kidney from Sham and NPX dams are shown in Figures 4A and 4B, respectively. The glomeruli of fetal kidneys from NPX dams were found to contain cells with condensed nuclei (arrows) while the number of these cells in glomeruli of fetal kidneys from Sham dams was minimal. Sections of fetal kidney from Sham and NPX dams were scored based on the number of cells with condensed nuclei present in a single glomerulus. The histopathology score for fetal kidneys from Sham rats (1.6 ± 0.16) was significantly lower than the score for fetal kidneys from NPX rats (3.1 ± 0.28).

Figure 4. Histological Analyses of Fetal and Maternal Kidneys.

Fetal and maternal kidneys were analyzed for histological changes following exposure to 2.0 mg/kg methylmercury via oral gavage. Inflammatory cells (arrows) were observed more frequently in glomeruli of fetal kidneys from NPX dams (B) than in those of fetal kidneys from Sham dams (A). Proximal (*) and distal (arrowheads) tubules in the cortex (C) and outer stripe of the outer medulla (OSOM) (E) of Sham dams appeared normal. In contrast, tubules in the cortex (D) and OSOM (F) of NPX dams were approximately 50% larger in diameter than corresponding tubules from Sham dams. Bar = 50 μm.

The normal renal cortex and OSOM from Sham dams are shown in Figures 4C and 4E, respectively. Glomeruli, proximal tubules and distal tubules are all of normal size with no pathological change. In contrast, Figures 4D and 4F show renal cortex and OSOM, respectively, from NPX dams. Glomeruli (G), proximal tubules (*), and distal tubules (arrowheads) are hypertrophied significantly in sections from NPX dams. The mean diameter of glomeruli of NPX dams was 119.12 ± 2.56 μm, which was approximately 23% larger, and significantly different, than those of Sham dams (96.71 ± 2.79). The glomerular diameter of Sham rats was similar to that reported in published studies. [25] Glomerular volume was calculated based on the measurements of diameter. The mean volume of glomeruli from NPX dams was 0.91 ± 0.06 × 106 μm3, which was significantly different than the mean glomerular volume in Sham dams (0.49 ± 0.05 × 106 μm3). Similarly, proximal tubules of NPX dams were 40% larger in diameter, and significantly different, than those of Sham dams (NPX diameter: 58.95 ± 1.37 μm; Sham diameter: 42.01 ± 1.77 μm).

3.4. Serum Creatinine

Serum creatinine levels from Sham and NPX dams were found to be 0.3219 ± 0.1872 mg/dL and 0.8118 ± 0.1697 mg/dL, respectively. Serum creatinine levels measured in Sham dams were similar to published normal values [26–28]. In contrast, serum creatinine levels in NPX dams were significantly greater than those of Sham dams.

3.5. Amount of Hg in Maternal Organs

The amount of Hg in the total renal mass of NPX dams was significantly less than that of Sham dams (Figure 5A). Similarly, the amount of Hg in the renal cortex was significantly lower in NPX dams than that in Sham dams (Figure 5B). In addition, the amount of Hg in the OSOM was significantly lower in NPX dams than that in Sham dams (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Amount of Hg in Kidneys of Dams.

Following exposure of pregnant Sham or 75% nephrectomized (NPX) rats to 2.0 mg/kg methylmercury, the amount of Hg in the total renal mass (A), cortex (B), and outer stripe of the outer medulla (OSOM) (C) was significantly lower in Sham dams than in NPX dams. *, significantly different (p < 0.05) from the mean of the corresponding group of Sham rats. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Sham: n = 8 dams. NPX: n = 5 dams.

The amount of Hg in blood (Figure 6A) and liver (Figure 6B) of NPX dams was significantly greater than that in blood and liver, respectively, of Sham dams. In contrast, the amount of Hg in brain (Figure 7A) and uterus (Figure 7B) of NPX dams was not significantly different than that in brain and uterus, respectively, of Sham dams.

Figure 6. Burden of Hg in Blood and Liver of Dams.

When pregnant Sham or 75% nephrectomized (NPX) rats were exposed to 2.0 mg/kg methylmercury, the amount of Hg in blood (A) and liver (B) of NPX dams was significantly greater than that in corresponding organs of Sham dams. *, significantly different (p < 0.05) from the mean of the corresponding group of Sham rats. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Sham: n = 8 dams. NPX: n = 5 dams.

Figure 7. Amount of Hg in Brain and Uterus of Dams.

In pregnant Sham or 75% nephrectomized (NPX) rats exposed to 2.0 mg/kg methylmercury, the amount of Hg in brain (A) and uterus (B) of NPX dams was not significantly greater than that in corresponding organs of Sham dams. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Sham: n = 8 dams. NPX: n = 5 dams.

The urinary (Figure 8A) and fecal (Figure 8B) excretion of Hg was significantly lower in NPX dams than in Sham dams.

Figure 8. Amount of Hg Excreted in Urine and Feces of Dams.

The amount of Hg in urine (A) and feces (B) of NPX dams exposed to 2.0 mg/kg methylmercury was significantly lower than that in urine and feces, respectively, of corresponding Sham dams. *, significantly different (p < 0.05) from the mean of the corresponding group of Sham rats. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Sham: n = 8 dams. NPX: n = 5 dams.

4. Discussion

There are a number of studies showing that CKD in pregnant women may lead to significant adverse outcomes in fetuses [29, 30]. Surprisingly, there are no published data on the handling of toxicants by pregnant women with CKD. Although exposure to environmental toxicants has decreased in the last decade, pregnant women continue to be exposed to heavy metals such as cadmium, arsenic, lead, and mercury [31]. It is well-established that exposure to mercury (Hg) and other heavy metals may enhance the progression of CKD [16, 23]. It has also been shown that exposure of pregnant women to various forms of Hg can lead to more frequent adverse outcomes such as pre-eclampsia and low birth weight infants [32]. When CKD, pregnancy, and exposure to environmental toxicants are combined, pregnant women and fetuses are at risk of more severe and/or more frequent adverse outcomes. Therefore, the current study was designed to determine if fetuses of pregnant mothers with renal disease are more susceptible to accumulation and retention of Hg. The current data demonstrate that renal insufficiency in mothers alters Hg accumulation in fetal kidneys following maternal exposure to methylmercury, which may make fetuses more susceptible to the toxic effects of Hg.

The current data provide valuable insight into the fetal handling of Hg. Although there was no significant difference in the total fetal burden of Hg between NPX and Sham dams, the fetal kidneys of NPX dams accumulated more Hg than fetal kidneys of Sham dams. Interestingly, histological analyses of fetal kidneys show an increased presence of cells with condensed nuclei in the developing glomeruli of fetal kidneys from NPX dams. The identity and significance of these cells is unknown at present. This finding correlates with the finding that more Hg accumulated in the kidneys of fetuses from NPX dams than in kidneys of fetuses from Sham dams. Therefore, the nuclear condensation may be a sign of apoptosis. Accumulation of Hg in fetal kidneys may be related to the flow of amniotic fluid, maternal handling of Hg, and/or underdeveloped mechanisms for cellular export and urinary excretion. Amniotic fluid is produced initially by dialysis of maternal and fetal blood through the placenta, meaning that Hg in maternal blood may become a component of amniotic fluid in this way. During gestation, amniotic fluid is recirculated through the fetal kidneys by repeated swallowing and urination. This repeated circulation extends the time to which kidneys are exposed to Hg and thus increases the risk of Hg absorption by the cells within the developing kidney. Underdeveloped mechanisms for cellular export of Hg may lead to retention of Hg within renal cells and contribute to renal accumulation. Future analyses of the expression of transporters involved in the uptake and export of Hg are necessary to characterize further this process. Interestingly, in the current study, the amount of Hg in the amniotic fluid collected from NPX dams was not significantly different than that collected from Sham dams. We propose that the hematologic delivery of Hg to the placenta and amniotic fluid of NPX dams is greater than that of Sham dams, which would result in a temporary increase in the Hg concentration of amniotic fluid. This increase would lead to enhanced accumulation of Hg in fetal kidneys of NPX dams. Indeed, the amount of mercury in blood of NPX dams was significantly greater than that of Sham dams. Measurements of plasma creatinine suggested that glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was reduced significantly in NPX dams, which would lead to reduced maternal clearance of Hg and consequent retention in blood. Taken together, these findings suggest that in mothers with renal insufficiency, fetal kidneys may be particularly susceptible to injury from toxicants, xenobiotics, or other drugs to which the mother may be exposed.

Interestingly, there was no difference in the placental content of mercury between NPX and Sham dams. This finding suggests that the concentration of mercury in the amniotic fluid, rather than that in the placenta, is an important factor in fetal accumulation of mercury. The lack of difference in placental accumulation between NPX and Sham dams may relate to the way methylmercury is transported across the placenta. Methylmercury appears to be transported across the placenta via neutral amino acid transporters such as Lat1 and Lat2 [33–36]. Given the abundance of amino acid transporters in the apical and basolateral membranes of placental syncytiotrophoblasts, it is reasonable to suggest that methylmercury is transported easily across the placenta and thus, accumulation of mercury within the placenta itself is likely minimal. Therefore, one would expect that the amount of methylmercury transported across the placenta to the fetal circulation is directly proportional to the amount of methylmercury present in maternal blood presented to the placenta.

It is interesting that the amount of mercury that accumulated in the fetal liver was similar between Sham and NPX dams. This lack of difference is likely related to fetal blood supply in that the blood supply to the fetal liver is relatively low and thus, delivery of Hg to the liver is likely minimal. However, it is important to point out that prenatal exposure to methylmercury has been shown to cause ultrastructural changes in the fetal liver [37]. These changes, along with potential renal injury, could negatively affect overall fetal health.

As mentioned above, the amount of Hg in blood of NPX dams was greater than that of Sham dams. This finding is most likely related to reduced renal plasma flow, reduced GFR, and consequent decreased renal clearance of Hg in NPX dams. Although glomerular and tubular hypertrophy occurred in NPX dams as normal compensatory mechanisms for the loss of renal mass, the reduction in renal plasma flow and GFR led to an overall reduction in the filtration of Hg. Consequently, the renal accumulation of Hg in the NPX rats was significantly lower than that in Sham rats. One could consider renal insufficiency to be somewhat protective against renal accumulation of nephrotoxicants, particularly since the histological analyses did not show evidence of pathological change in the remnant renal mass. It should be considered that circulating biomarkers for renal injury could reveal cellular injury that is not visible microscopically, yet these were not measured in the current study as they could also be attributed to the surgical procedure. As noted earlier, the inability to filter and excrete nephrotoxicants leads to enhanced accumulation in the blood, which leads to enhanced delivery to other blood-rich organs such as the liver. Fecal elimination of mercury was minimal throughout the exposure period; therefore, it is possible that prolonged exposure to methylmercury could lead to hepatic injury [38].

The amount of Hg detected in the brain was similar between NPX and Sham dams. This lack of difference is likely because the selectivity of the blood brain barrier prevents a large fraction of Hg from gaining access to the brain. Similarly, there was no significant difference in uterine content of Hg between Sham and NPX dams. This finding was surprising in that one would expect the uterine content of Hg to reflect that of the hematologic content. The cause of this discrepancy remains unclear at present.

Not only do the current data provide important insight into the handling of Hg in fetuses from mothers with renal insufficiency, but they also reinforce previous studies showing that renal disease may lead to poor fetal outcomes. Body and organ weights for fetuses from NPX dams were significantly lower than those from Sham dams. A number of studies have found that small for gestational age (SGA) babies is a frequent outcome in mothers with renal disease [2–4].

In summary, the current data are the first to show that renal insufficiency in mothers leads to significant alterations in the accumulation of mercury in fetal organs. Enhanced accumulation of mercury by fetal kidneys may lead to renal injury and/or insufficiency in the prenatal and perinatal stages of life. Pregnant women in high-risk populations should be provided adequate education regarding their renal function and exposure to toxicants such as mercury. Epidemiological studies show that Asian-Americans and Hispanics have a greater risk of CKD than their Caucasian counterparts, mainly because of a greater incidence of risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) and lack of adequate health care and education [39–41]. Furthermore, their diets tend to be high in fish, which puts them at greater risk for exposure to methylmercury [42, 43]. Continued exposure of pregnant women in these populations to methylmercury when they are in a state of renal insufficiency could put the health of their fetus in jeopardy.

Highlights.

Sham and nephrectomized (NPX) pregnant rats were exposed orally to methylmercury

Fetal kidneys from NPX dams accumulated more mercury than those from Sham dams

Mercury in blood was greater in NPX dams which enhanced delivery to fetuses

Renal insufficiency in mothers may enhance fetal accumulation of toxicants

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (ES019991) and Navicent Health Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC, National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet: General Information and National Estimates on Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, in: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; (Ed.) Atlanta, GA, (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hladunewich MA, Chronic Kidney Disease and Pregnancy, Sem Nephrol 37(4) (2017) 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Piccoli GB, Fassio F, Attini R, Parisi S, Biolcati M, Ferraresi M, Pagano A, Daidola G, Deagostini MC, Gaglioti P, Todros T, Pregnancy in CKD: whom should we follow and why?, Nephrol Dial Transplant 27 Suppl 3 (2012) iii111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhang JJ, Ma XX, Hao L, Liu LJ, Lv JC, Zhang H, A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Outcomes of Pregnancy in CKD and CKD Outcomes in Pregnancy, Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10(11) (2015) 1964–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sommar JN, Svensson MK, Bjor BM, Elmstahl SI, Hallmans G, Lundh T, Schon SM, Skerfving S, Bergdahl IA, End-stage renal disease and low level exposure to lead, cadmium and mercury; a population-based, prospective nested case-referent study in Sweden, Environ Health: a global access science source 12 (2013) 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Farzan SF, Howe CG, Chen Y, Gilbert-Diamond D, Cottingham KL, Jackson BP, Weinstein AR, Karagas MR, Prenatal lead exposure and elevated blood pressure in children, Environ Int 121(Pt 2) (2018) 1289–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].De Long NE, Holloway AC, Early-life chemical exposures and risk of metabolic syndrome, Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity : Targets and Therapy 10 (2017) 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Akerstrom M, Barregard L, Lundh T, Sallsten G, Relationship between mercury in kidney, blood, and urine in environmentally exposed individuals, and implications for biomonitoring, Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 320 (2017) 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mortensen ME, Caudill SP, Caldwell KL, Ward CD, Jones RL, Total and methyl mercury in whole blood measured for the first time in the U.S. population: NHANES 2011–2012, Environ Res 134 (2014) 257–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shim YK, Lewin MD, Ruiz P, Eichner JE, Mumtaz MM, Prevalence and associated demographic characteristics of exposure to multiple metals and their species in human populations: The United States NHANES, 2007–2012, J Toxicol Environ Health A 80(9) (2017) 502–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bridges CC, Zalups RK, Mechanisms involved in the transport of mercuric ions in target tissues, Arch Toxicol 91(1) (2016) 63–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Haseler E, Melhem N, Sinha MD, Renal disease in pregnancy: Fetal, neonatal and long-term outcomes, Best practice & research. Clin Obst Gyn 57 (2019) 60–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Iwai-Shimada M, Kameo S, Nakai K, Yaginuma-Sakurai K, Tatsuta N, Kurokawa N, Nakayama SF, Satoh H, Exposure profile of mercury, lead, cadmium, arsenic, antimony, copper, selenium and zinc in maternal blood, cord blood and placenta: the Tohoku Study of Child Development in Japan, Environ Health Prev Med 24(1) (2019) 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ong CN, Chia SE, Foo SC, Ong HY, Tsakok M, Liouw P, Concentrations of heavy metals in maternal and umbilical cord blood, Biometals 6(1) (1993) 61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tchounwou PB, Ayensu WK, Ninashvili N, Sutton D, Environmental exposure to mercury and its toxicopathologic implications for public health, Environ Toxicol 18(3) (2003) 149–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tsai CC, Wu CL, Kor CT, Lian IB, Chang CH, Chang TH, Chang CC, Chiu PF, Prospective associations between environmental heavy metal exposure and renal outcomes in adults with chronic kidney disease, Nephrology (Carlton) 23(9) (2018) 830–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Oliveira CS, Joshee L, Zalups RK, Pereira ME, Bridges CC, Disposition of inorganic mercury in pregnant rats and their offspring, Toxicology 335 (2015) 62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sakamoto M, Yasutake A, Domingo JL, Chan HM, Kubota M, Murata K, Relationships between trace element concentrations in chorionic tissue of placenta and umbilical cord tissue: potential use as indicators for prenatal exposure, Environ Int 60 (2013) 106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yorifuji T, Tsuda T, Takao S, Suzuki E, Harada M, Total mercury content in hair and neurologic signs: historic data from Minamata, Epidemiology 20(2) (2009) 188–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P, Chronic Kidney Disease, Lancet 389(10075) (2017) 1238–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bridges CC, Joshee L, Zalups RK, Effect of DMPS and DMSA on the Placental and Fetal Disposition of Methylmercury, Placenta 30(9) (2009) 800–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rouleau C, Block M, Fast and high yield synthesisi of radioactive CH3203Hg(II)., Appl. Organomet. Chem 11(9) (1997) 751–753. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Urano T, Imura N, Naganuma A, Inhibitory effect of selenium on biliary secretion of methyl mercury in rats, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 239(3) (1997) 862–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lee HB, Blaufox MD, Blood volume in the rat, J Nucl Med 26(1) (1985) 72–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kotyk T, Dey N, Ashour AS, Balas-Timar D, Chakraborty S, Tavares JM, Measurement of glomerulus diameter and Bowman’s space width of renal albino rats, Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 126 (2016) 143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Amini FG, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Nematbakhsh M, Baradaran A, Nasri H, Ameliorative effects of metformin on renal histologic and biochemical alterations of gentamicin-induced renal toxicity in Wistar rats, Journal of research in medical sciences : the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences 17(7) (2012) 621–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bridges CC, Joshee L, Zalups RK, Aging and the disposition and toxicity of mercury in rats, Experimental gerontology 53 (2014) 31–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Moeini M, Nematbakhsh M, Fazilati M, Talebi A, Pilehvarian AA, Azarkish F, Eshraghi-Jazi F, Pezeshki Z, Protective role of recombinant human erythropoietin in kidney and lung injury following renal bilateral ischemia-reperfusion in rat model, Inter J Prev Med 4(6) (2013) 648–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Li Y, Wang W, Wang Y, Chen Q, Fetal Risks and Maternal Renal Complications in Pregnancy with Preexisting Chronic Glomerulonephritis, Med Sci Monitor 24 (2018) 1008–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bharti J, Vatsa R, Singhal S, Roy KK, Kumar S, Perumal V, Meena J, Pregnancy with chronic kidney disease: maternal and fetal outcome, European J Obst Gyn Repro Bio 204 (2016) 83–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bulka CM, Bommarito PA, Fry RC, Predictors of toxic metal exposures among US women of reproductive age, J Exposure Sci Environ Epidemiol (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].El-Badry A, Rezk M, El-Sayed H, Mercury-induced Oxidative Stress May Adversely Affect Pregnancy Outcome among Dental Staff: A Cohort Study, Int J Occupat Environ Med 9(3) (2018) 113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Aschner M, Clarkson TW, Distribution of mercury 203 in pregnant rats and their fetuses following systemic infusions with thiol-containing amino acids and glutathione during late gestation, Teratology 38(2) (1988) 145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Straka E, Ellinger I, Balthasar C, Scheinast M, Schatz J, Szattler T, Bleichert S, Saleh L, Knofler M, Zeisler H, Hengstschlager M, Rosner M, Salzer H, Gundacker C, Mercury toxicokinetics of the healthy human term placenta involve amino acid transporters and ABC transporters, Toxicology 340 (2016) 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kajiwara Y, Yasutake A, Adachi T, Hirayama K, Methylmercury transport across the placenta via neutral amino acid carrier, Arch Toxicol 70(5) (1996) 310–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Balthasar C, Stangl H, Widhalm R, Granitzer S, Hengstschlager M, Gundacker C, Methylmercury Uptake into BeWo Cells Depends on LAT2–4F2hc, a System L Amino Acid Transporter, Int J Mol Sci 18(8) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ware RA, Chang LW, Burkholder PM, Ultrastructural evidence for foetal liver injury induced by in utero exposure to small doses of methylmercury, Nature 251(5472) (1974) 236–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Desnoyers PA, Chang LW, Ultrastructural changes in rat hepatocytes following acute methyl mercury intoxication, Environ Res 9(3) (1975) 224–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].NKF NKF, Asian Americans and Kidney Disease, 2015. https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/AsianAmericans-KD. (Accessed 08–12-2019.

- [40].Sabanayagam C, Lim SC, Wong TY, Lee J, Shankar A, Tai ES, Ethnic disparities in prevalence and impact of risk factors of chronic kidney disease, Nephrol Dial Transplant 25(8) (2010) 2564–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lora CM, Daviglus ML, Kusek JW, Porter A, Ricardo AC, Go AS, Lash JP, Chronic kidney disease in United States Hispanics: a growing public health problem, Ethn Dis 19(4) (2009) 466–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Liu Y, Buchanan S, Anderson HA, Xiao Z, Persky V, Turyk ME, Association of methylmercury intake from seafood consumption and blood mercury level among the Asian and Non-Asian populations in the United States, Environ Res 160 (2018) 212–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Carter-Pokras O, Zambrana RE, Poppell CF, Logie LA, Guerrero-Preston R, The environmental health of Latino children, Journal of pediatric health care, J Pediatr Health Care 21(5) (2007) 307–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]