Abstract

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a fatal infectious disease of wild and domestic cats, and the occurrence of FIP is frequently reported in China. To trace the evolution of type I and II feline coronavirus in China, 115 samples of ascetic fluid from FIP‐suspected cats and 54 fecal samples from clinically healthy cats were collected from veterinary hospitals in China. The presence of FCoV in the samples was detected by RT‐PCR targeting the 6b gene. The results revealed that a total of 126 (74.6%, 126/169) samples were positive for FCoV: 75.7% (87/115) of the FIP‐suspected samples were positive for FCoV, and 72.2% (39/54) of the clinically healthy samples were positive for FCoV. Of the 126 FCoV‐positive samples, 95 partial S genes were successfully sequenced. The partial S gene‐based genotyping indicated that type I FCoV and type II FCoV accounted for 95.8% (91/95) and 4.2% (4/95), respectively. The partial S gene‐based phylogenetic analyses showed that the 91 type I FCoV strains exhibited genetic diversity; the four type II FCoV strains exhibited a close relationship with type II FCoV strains from Taiwan. Three type I FCoV strains, HLJ/HRB/2016/10, HLJ/HRB/2016/11 and HLJ/HRB/2016/13, formed one potential new clade in the nearly complete genome‐based phylogenetic trees. Further analysis revealed that FCoV infection appeared to be significantly correlated with a multi‐cat environment (p < 0.01) and with age (p < 0.01). The S gene of the three type I FCoV strains identified in China, BJ/2017/27, BJ/2018/22 and XM/2018/04, exhibited a six nucleotide deletion (C4035 AGCTC 4040). Our data provide evidence that type I and type II FCoV strains co‐circulate in the FIP‐affected cats in China. Type I FCoV strains exhibited high prevalence and genetic diversity in both FIP‐affected cats and clinically healthy cats, and a multi‐cat environment and age (<6 months) were significantly associated with FCoV infection.

Keywords: feline coronavirus, feline infectious peritonitis, genetic diversity, phylogenetic analysis, S gene

1. INTRODUCTION

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a fatal infectious disease in wild and domestic cats, characterized by fibrinous and granulomatous serositis, protein‐rich serous effusion in body cavities, and/or granulomatous inflammatory lesions (Wolfe & Griesemer, 1966). The causative agent of FIP has been revealed to be feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) which arises from feline enteric coronavirus (FECV). Feline coronavirus (FCoV), together with canine coronavirus (CCoV) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus of pigs, belongs to the species Alphacoronavirus 1, the genus Alphacoronavirus, the subfamily Coronavirinae, the family Coronaviridae, and the order Nidovirales. FCoVs are single‐stranded positive sense RNA viruses with an approximately 29 kb nonsegmented genome, which consisting of 11 open reading frames (ORFs) (Myrrha et al., 2011). FCoVs are classified into two serotypes, type I and type II FCoVs, according to their serological properties; they are also separated into two biotypes, FECV and FIPV, based on pathogenicity. These two biotypes, FECV and FIPV, exist in both serotypes I and II (Tekes & Thiel, 2016). Both type I and type II FCoVs can cause FIP. FIP remains one of the most frequently fatal infectious feline diseases for which there are no effective therapies.

Type I FCoV infection exhibits a high prevalence in Europe and America, reaching 80%–95%, while type II FCoVs are reportedly less common in the field (Benetka et al., 2004; Kummrow et al., 2005). However, type II FCoV infection has predominantly been observed in various Asian countries, reaching 25% (Amer et al., 2012; An et al., 2011; Sharif et al., 2010). Double homologous recombination between type I FCoV and CCoV leads to the emergence of type II FCoV (Decaro & Buonavoglia, 2008; Haijema, Rottier, & de Groot, 2007; Herrewegh, Smeenk, Horzinek, Rottier, & de Groot, 1998; Lin, Chang, Su, & Chueh, 2013; Lorusso et al., 2008; Terada et al., 2014). These data indicate that the causative agent of FIP exhibits immense complexity in different countries and areas. The occurrence of FCoV is frequently reported in China and attracts extensive concern due to its high mortality rate. At present, little information is available on the molecular epidemiology of FCoV in China. In this study, molecular epidemiological investigation of FCoV was carried out in China from November 2015 to January 2018. Partial S genes and nearly complete genomes were used to analyze the genetic evolution of the FCoV strains identified. The aim of the study was to provide insights into the epidemiology and genetic diversity of the FCoV strains circulating in China. The resulting data will provide valuable information for prevention and control of FCoV infections.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Ethics statements

The current study was approved by the Animal Experiments Committee of the Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University (registration protocol 01/2015). The field study did not involve endangered or protected species. No specific permissions were required for location of samples because the samples were collected from public areas or non‐protected areas. The sampling and data publication were approved by the cats’ owners.

2.2. Sample collection

In total, 169 samples were collected from veterinary hospitals in China from November 2015 to January 2018 using commercial virus sampling tubes (YOCON Biological Technology Co. Ltd. Beijing, China) with a volume of 3.5 ml. The 169 samples were sourced from Beijing (n = 83), Harbin of Heilongjiang province (n = 17), Daqing of Heilongjiang province (n = 28), Qiqihar of Heilongjiang province (n = 2), Dalian of Liaoning province (n = 4), Chengdu of Sichuan province (n = 14), Huzhou of Zhejiang province (n = 3), Haining of Zhejiang province (n = 4), Xining of Qinghai province (n = 6), and Xiamen of Fujian province (n = 8). For all samples, the cat's age, breed, gender, and collection date were recorded. Of the 169 samples, 54 fecal samples were obtained from clinically healthy cats and 115 samples of ascetic fluid were obtained from FIP‐suspected cats. Clinical diagnosis was made for the diseased cats mainly as described by Addie et al. (2009). The FIP‐suspected cats were detected using routine blood parameters, blood biochemical parameters, ultrasonography, and the Rivalta test. The clinical signs shown by the FIP‐suspected cats were thoracic effusion, inappetence, anorexia, weight loss, lethargy, icterus, fever, diarrhea, leukocytosis, decrease in lymphocytes, an albumin: globulin ratio <0.8, and ascitic fluid were positive on the Rivalta test. All samples were stored at −80°C.

2.3. Detection of Feline coronavirus

Feline coronavirus infection was detected by RT‐PCR targeting the 6b gene. For amplification of the 6b gene of FCoV, RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were carried out according to the protocol described by Wang et al. (2016). Random primers (six nucleotides) were used for synthesis of the first‐strand cDNA. The PCR amplification of the 6b gene was carried out according to the protocol described by Herrewegh et al. (1995).

2.4. Genotyping of the FCoV strains identified

In order to differentiate the type I and type II FCoV strains identified in our study, the partial S gene was amplified by RT‐PCR using the primers described by Lin et al. (2009). The purified PCR products of the partial S genes were directly subjected to Sanger sequencing. All nucleotide sequences generated in our study were submitted to GenBank. Sequence analysis was performed using the EditSeq tool in Lasergene DNASTAR™ 5.06 software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI). Multiple sequence alignments were performed using the Multiple Sequence Alignment tool of DNAMAN 6.0 software (Lynnon BioSoft, Point‐Claire, Quebec, Canada).

2.5. Illumina next‐generation sequencing of 50 selected samples

In order to obtain the entire genome of the identified FCoV strains, the cDNAs of 50 selected samples were sequenced by Illumina next‐generation sequencing (Shanghai Biozeron Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Briefly, RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis for the 50 samples were carried out according to the protocol described by Wang et al. (2016) using random primers (six nucleotides) and an oligo dT18 primer. The double‐stranded DNA was synthesized by second strand cDNA synthesis kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, 150 ng of cDNA was used to construct a library according to the manufacturer's instructions (TruSeq Nano DNA HT Library Prep Kit), and loaded on to a HiSeq × ten for sequencing. Raw sequence reads were trimmed to remove the reads of the adaptor, duplicate reads and host genomic sequences. The trimmed reads were assembled using SOAPdenovo v2.04 (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/), and the assembled genomes were corrected using GapCloser v1.12 software. Viral genes were predicted using the software GeneMarkS (http://topaz.gatech.edu/GeneMark/genemarks.cgi), and annotation of the predicted viruses was carried out through the nonredundant protein database (NR) using BLASTp. In this study, the nearly complete genomes of four FCoV strains were obtained, according to the porcine coronavirus PEDV described by Marthaler et al. (2013). After genome assembly, the single genomic gap of the four FCoV strains was closed using standard Sanger sequencing technology. A similarity plots analysis of the genomes of the FCoV strains identified in our study was performed by the sliding window method as implemented in the SimPlot, v.3.5.1 package (Lole et al., 1999).

2.6. Phylogenetic analysis

For the phylogenetic analysis, the partial S genes and nearly complete genome sequences of the FCoV strains were retrieved from GenBank. To construct phylogenetic trees, multiple alignments of all target sequences were carried out using the Clustal X program version 1.83 (Thompson, Gibson, Plewniak, Jeanmougin, & Higgins, 1997). Furthermore, the phylogenetic trees of all target sequences were generated from the Clustal X‐generated alignments by MEGA 6.06 software using the neighbor‐joining method (Tamura, Stecher, Peterson, Filipski, & Kumar, 2013). Neighbor‐joining phylogenetic trees were built with the p‐distance model, 1,000 bootstrap replicates, and otherwise default parameters in MEGA 6.06 software. Phylogenetic trees were pruned and re‐rooted by using the Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) software version 4.2.3 (https://itol.embl.de/) which is an online tool for displaying the circular tree and annotation (Letunic & Bork, 2007).

2.7. Statistical analysis

The correlation of FCoV infection with clinical signs, geographical location (South China or north China), living environment, gender, breed, and age, was carried out in 2 × 2 contingency tables using the chi‐square test with Fisher's exact test in IBM SPSS Statistics, version 19.0. A multi‐cat environment was defined when the number of cats was ≥3. The difference in values was considered statistically significant or highly significant if the associated p value was <0.05 or <0.01, respectively.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Detection and analysis of FCoV

From November 2015 to January 2018, a total of 115 FIP‐suspected samples of ascetic fluid and 54 fecal samples from veterinary hospitals in China were tested via PCR amplification of the 6b gene of FCoV. Of the 169 samples, 126 (74.6%, 126/169) were positive for FCoV; the detailed information on the FCoV‐positive samples is shown in Supporting Information (Table S1). The positive rates of FCoV in FIP‐suspected and healthy cats were 75.7% (87/115) and 72.2% (39/54), respectively (Table 1). The positive rates of FCoV from South China and North China were 80.0% (28/35) and 73.1% (98/134), respectively (Table 1). The positive rates of FCoV in a multi‐cat environment and in single cat households were 93.8% (30/32) and 70.1% (96/137), respectively (Table 1). The prevalence of FCoV was significantly correlated with living environment (p = 0.006) and age (p = 0.008), while FCoV infection was not significantly associated with clinical signs (p = 0.633), geographical location (p = 0.406), sex (p = 0.792) or breed (p = 0.994) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlation of the FCoV prevalence with clinical symptoms, geographical location, living environments, gender, breed and age

| Variables | Number of samples (n = 169) | Number of FCoV‐positive samples | Number of FCoV‐negative samples | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical status | ||||||

| FIP‐suspected cats | 115 | 87 | 28 | 1.060 | 0.827–1.359 | 0.633 |

| Healthy cats | 54 | 39 | 15 | 0.887 | 0.547–1.440 | |

| Geographical location | ||||||

| South China | 35 | 28 | 7 | 1.365 | 0.643–2.897 | 0.406 |

| North China | 134 | 98 | 36 | 0.929 | 0.790–1.092 | |

| Living environment | ||||||

| Single cat household | 137 | 96 | 41 | 0.799 | 0.710–0.899 | 0.006 |

| Multi‐cat environment | 32 | 30 | 2 | 5.119 | 1.276–20.529 | |

| Gender | n = 121 | |||||

| Female | 50 | 37 | 13 | 1.067 | 0.654–1.741 | 0.792 |

| Male | 71 | 51 | 20 | 0.956 | 0.689–1.327 | |

| Breed | n = 86 | |||||

| Pure breed | 66 | 55 | 11 | 1.056 | 0.759–1.469 | 0.994 |

| Cross breed | 20 | 16 | 4 | 0.845 | 0.329–2.171 | |

| Age | n = 137 | |||||

| <6 months | 45 | 39 | 6 | 2.495 | 1.151–5.409 | 0.008 |

| ≥6 months | 92 | 60 | 32 | 0.720 | 0.583–0.888 | |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

3.2. Genotyping and sequence analysis of the FCoV strains

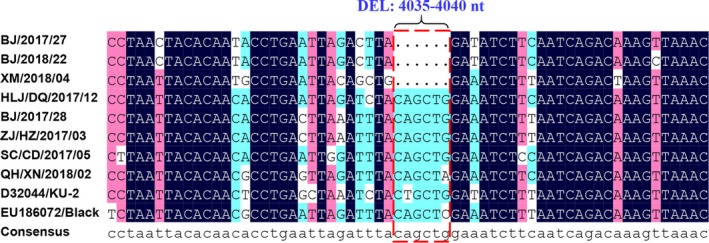

For genotyping of the FCoV strains identified in our study, the partial S gene was amplified by RT‐PCR. Of the 126 FCoV positive samples, a total of 95 partial S genes were successfully sequenced. Detailed information on the 95 FCoV‐positive samples is shown in Table 2. The partial S gene‐based genotyping indicated that, of the 95 FCoV samples, 91 samples (95.8%) were positive for type I FCoV, and four samples (4.2%) were positive for type II FCoV (Table 3). The sequence analysis of the partial S gene revealed nucleotide homology of 56.2%–100.0% and amino acid homology of 46.3%–100.0%, respectively, among the 95 FCoV strains. The 91 type I FCoV strains identified had nucleotide homology of 80.4%–100.0% and amino acid homology of 78.6%–100.0%, while nucleotide and amino acid homologies of 97.6%–99.4% and 96.4%–100.0% were observed among the four type II FCoV strains, respectively. The 91 type I FCoV strains exhibited 80.4%–100.0% nucleotide sequence homology and 78.6%–100.0% amino acid sequence homology with the type I FCoV reference strain KU‐2 (GenBank accession no. D32044). Nucleotide and amino acid homologies of 94.0%–99.4% and 96.4%–100.0%, respectively, were observed between the four identified type II FCoV strains and the type II FCoV reference strain 79–1146 (GenBank accession no. DQ010921). The three type I FCoV strains (BJ/2017/27, BJ/2018/22, and XM/2018/04) exhibited a six‐nucleotide deletion (C4035AGCTC4040) encoding two amino acids (Gln1345Leu1346) of S protein when compared with all identified type I FCoV strains and type I FCoV reference strains (KU‐2 strain and Black strain) (Figure 1). Of the three strains, BJ/2017/27 and BJ/2018/22 strains were identified in the FIP‐suspected cats, and the XM/2018/04 strain was identified in the clinically healthy cat.

Table 2.

The detailed information of the 95 FCoV‐positive samples (partial S genes) in this study

| No. | Strain name | Collection date | Living environment | Geographical location | Breed | Gender | Age | Sample source | Detection of FCoV based on 6b gene | Genotyping of FCoVs based on partial S gene | Genbank accession No. of partial S genes of FCoVs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I of FCoV | Type II of FCoV | |||||||||||

| 1 | BJ/2015/02 | Nov‐2015 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | ‐ | + | MG016684 |

| 2 | BJ/2015/03 | Dec‐2015 | Single cat household | Beijing city | DSH | F | 36M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016685 |

| 3 | BJ/2015/04 | Dec‐2015 | Single cat household | Beijing city | DSH | F | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016686 |

| 4 | HLJ/HRB/2016/01 | Mar‐2016 | Single cat household | Harbin city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016698 |

| 5 | HLJ/HRB/2016/03 | Mar‐2016 | Single cat household | Harbin city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016707 |

| 6 | HLJ/HRB/2016/04 | Mar‐2016 | Single cat household | Harbin city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016699 |

| 7 | HLJ/HRB/2016/05 | Mar‐2016 | Single cat household | Harbin city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016700 |

| 8 | HLJ/QQHR/2016/01 | Mar‐2016 | Single cat household | Qiqihar city, Heilongjiang | DSH | M | 2M | FSC | + | ‐ | + | MG016705 |

| 9 | BJ/2016/01 | Sep‐2016 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016690 |

| 10 | BJ/2016/02 | Sep‐2016 | Single cat household | Beijing city | ASH | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016691 |

| 11 | BJ/2016/03 | Sep‐2016 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016692 |

| 12 | BJ/2016/06 | Sep‐2016 | Single cat household | Beijing city | ASH | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016706 |

| 13 | HLJ/DQ/2016/01 | Oct‐2016 | Multi‐cat environment | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | Ragdoll | M | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016687 |

| 14 | HLJ/DQ/2016/02 | Oct‐2016 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016688 |

| 15 | HLJ/DQ/2016/03 | Oct‐2016 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | Ragdoll | NA | 6M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016689 |

| 16 | HLJ/HRB/2016/10 | Nov‐2016 | Multi‐cat environment | Harbin city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016701 |

| 17 | HLJ/HRB/2016/11 | Nov‐2016 | Multi‐cat environment | Harbin city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016702 |

| 18 | HLJ/HRB/2016/13 | Nov‐2016 | Single cat household | Harbin city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | 3M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016703 |

| 19 | HLJ/HRB/2016/17 | Nov‐2016 | Single cat household | Harbin city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | 4M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016704 |

| 20 | BJ/2016/09 | Nov‐2016 | Single cat household | Beijing city | BSH | NA | 3M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016693 |

| 21 | BJ/2016/14 | Dec‐2016 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | NA | F | 5M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016708 |

| 22 | BJ/2016/15 | Dec‐2016 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | NA | 7M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016694 |

| 23 | BJ/2016/16 | Dec‐2016 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | F | 4M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016695 |

| 24 | BJ/2016/17 | Dec‐2016 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | M | 6M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016696 |

| 25 | BJ/2016/19 | Dec‐2016 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | M | 12M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG016697 |

| 26 | SC/CD/2017/01 | Feb‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | NA | 3M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892395 |

| 27 | SC/CD/2017/02 | Feb‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | F | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892396 |

| 28 | SC/CD/2017/03 | Feb‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | F | 12M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892397 |

| 29 | HLJ/DQ/2017/03 | Mar‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | NA | F | 4M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892398 |

| 30 | BJ/2017/01 | Mar‐2017 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | M | 6M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892399 |

| 31 | BJ/2017/07 | Mar‐2017 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | M | 5M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892400 |

| 32 | BJ/2017/08 | Mar‐2017 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | F | 9M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892401 |

| 33 | BJ/2017/15 | Mar‐2017 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | F | 7M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892402 |

| 34 | BJ/2017/21 | Mar‐2017 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | NA | 36M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892403 |

| 35 | BJ/2017/23 | Apr‐2017 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | F | 5M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892404 |

| 36 | HLJ/DQ/2017/05 | Apr‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | ASH | F | 4M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892405 |

| 37 | HLJ/DQ/2017/06 | May‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | DSH | NA | NA | FSC | + | ‐ | + | MG892406 |

| 38 | HLJ/DQ/2017/07 | Jun‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892407 |

| 39 | HLJ/DQ/2017/08 | Jul‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892408 |

| 40 | HLJ/DQ/2017/09 | Aug‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | ASH | F | 4M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892409 |

| 41 | HLJ/DQ/2017/12 | Nov‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | DSH | F | 4M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892410 |

| 42 | SC/CD/2017/05 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | F | 4M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892421 |

| 43 | SC/CD/2017/06 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | M | 5M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892413 |

| 44 | SC/CD/2017/07 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | M | 7M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892422 |

| 45 | SC/CD/2017/09 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | M | 5M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892423 |

| 46 | SC/CD/2017/10 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | NA | 6M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892414 |

| 47 | SC/CD/2017/11 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | DSH | NA | 18M | FSC | + | ‐ | + | MG892415 |

| 48 | SC/CD/2017/12 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | DSH | M | 6M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892424 |

| 49 | SC/CD/2017/13 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | M | 5M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892425 |

| 50 | SC/CD/2017/14 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Chengdu city, Sichuan | NA | NA | 4M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892426 |

| 51 | BJ/2017/27 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Beijing city | ESH | M | 8M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892420 |

| 52 | LN/DL/2017/01 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Dalian city, Liaoning | BSH | M | 42M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892417 |

| 53 | LN/DL/2017/02 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Dalian city, Liaoning | Sphynx | M | 48M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892431 |

| 54 | XM/2017/01 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Xiamen city, Fujian | BSH | M | 4M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892418 |

| 55 | HLJ/DQ/2017/13 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | BSH | M | 5M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892416 |

| 56 | HLJ/DQ/2017/14 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | ESH | F | 8M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892427 |

| 57 | HLJ/DQ/2017/15 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | DSH | NA | 24M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892428 |

| 58 | HLJ/DQ/2017/17 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | DSH | F | 36M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892429 |

| 59 | HLJ/DQ/2017/20 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Daqing city, Heilongjiang | Chinchilla | M | 36M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892430 |

| 60 | ZJ/HZ/2017/01 | Dec‐2017 | Multi‐cat environment | Huzhou city, Zhejiang | BSH | F | 12M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892433 |

| 61 | ZJ/HZ/2017/02 | Dec‐2017 | Multi‐cat environment | Huzhou city, Zhejiang | BSH | M | 36M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892434 |

| 62 | ZJ/HZ/2017/03 | Dec‐2017 | Multi‐cat environment | Huzhou city, Zhejiang | BSH | F | 24M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892419 |

| 63 | BJ/2017/28 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Beijing city | ASH | M | 8M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892411 |

| 64 | BJ/2017/30 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Beijing city | DSH | F | 8M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892412 |

| 65 | LN/DL/2017/04 | Dec‐2017 | Single cat household | Dalian city, Liaoning | NA | M | 5M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892432 |

| 66 | XM/2018/01 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Xiamen city, Fujian | NA | M | 5M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892445 |

| 67 | XM/2018/04 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Xiamen city, Fujian | BSH | F | 5M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892446 |

| 68 | BJ/2018/01 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | Ragdoll | M | 6M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892435 |

| 69 | BJ/2018/02 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | Ragdoll | M | 11M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892436 |

| 70 | BJ/2018/03 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | BSH | M | 60M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892437 |

| 71 | BJ/2018/04 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | BSH | M | 36M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892438 |

| 72 | BJ/2018/05 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | BSH | M | NA | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892439 |

| 73 | BJ/2018/06 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | Ragdoll | F | 6M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892440 |

| 74 | BJ/2018/07 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | ESH | F | 60M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892441 |

| 75 | BJ/2018/08 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | ESH | F | 3M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892442 |

| 76 | BJ/2018/09 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | BSH | M | 3M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892443 |

| 77 | BJ/2018/11 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Beijing city | BSH | M | 6M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892444 |

| 78 | BJ/2018/13 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | DSH | M | 60M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892447 |

| 79 | BJ/2018/15 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | ESH | M | 66M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892448 |

| 80 | BJ/2018/16 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | BSH | M | 6M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892449 |

| 81 | BJ/2018/18 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | ASH | M | 6M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892450 |

| 82 | BJ/2018/22 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | ESH | M | 8M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892451 |

| 83 | ZJ/HN/2018/01 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Haining city, Zhejiang | DSH | M | 12M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892457 |

| 84 | ZJ/HN/2018/03 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Haining city, Zhejiang | BSH | M | 9M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892458 |

| 85 | ZJ/HN/2018/04 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Haining city, Zhejiang | BSH | F | 8M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892459 |

| 86 | QH/XN/2018/01 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Xining city, Qinghai | BSH | M | 5M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892452 |

| 87 | QH/XN/2018/02 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Xining city, Qinghai | Ragdoll | M | 25M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892453 |

| 88 | QH/XN/2018/03 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Xining city, Qinghai | BSH | M | 4M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892454 |

| 89 | QH/XN/2018/05 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Xining city, Qinghai | ASH | F | 5.5M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892455 |

| 90 | QH/XN/2018/06 | Jan‐2018 | Multi‐cat environment | Xining city, Qinghai | ASH | M | 6M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892456 |

| 91 | BJ/2018/25 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892460 |

| 92 | BJ/2018/26 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | NA | NA | NA | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892461 |

| 93 | BJ/2018/27 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | Ragdoll | F | 17M | FSC | + | + | ‐ | MG892462 |

| 94 | BJ/2018/28 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | ASH | M | 24M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892463 |

| 95 | BJ/2018/29 | Jan‐2018 | Single cat household | Beijing city | BSH | F | 4M | CHC | + | + | ‐ | MG892464 |

For breed, ASH:American Shorthair; BSH: British Shorthair; DSH: Domestic Shorthair; ESH: Exotic Shorthair.

For gender, F: female, and M: male.

For age, M: month. NA: not available.

For sample source, CHC: clinically healthy cat; FSC: FIP‐suspected cat.

“+” represents positive results of viral detection; “–”represents negative results of viral detection.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Table 3.

Genotyping of FCoV strains identified in this study

| Clinical status | Number of samples | Number of FCoV‐positive samples based on the 6b gene | Genotyping of FCoV based on the partial S gene | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I FCoV | Type II FCoV | Untypable FCoV | |||

| FIP‐suspected cats | 115 | 87/115 (75.7%) | 56/60 (93.3%) | 4/60 (6.7%) | 27 |

| 95% CI (0.678–0.835) | 95% CI (0.870‐0.996) | 95% CI (0.035–0.130) | |||

| Healthy cats | 54 | 39/54 (72.2%) | 35/35 (100%) | 0/35 (0%) | 4 |

| 95% CI (0.603–0.842) | 95% CI (1.000‐1.000) | 95% CI (‐) | |||

| Total | 169 | 126 | 91 | 4 | 31 |

CI: confidence interval.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Figure 1.

Alignment analyses of the nucleotide sequences of partial S genes between the identified type I FCoV strains and reference strains. Note. The selected type I FCoV strains identified in our study were shown in the Figure 1. Nucleotide location was determined according to the S gene of FCoV Black strain (GenBank accession no. EU186072) [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3. Phylogenetic analysis

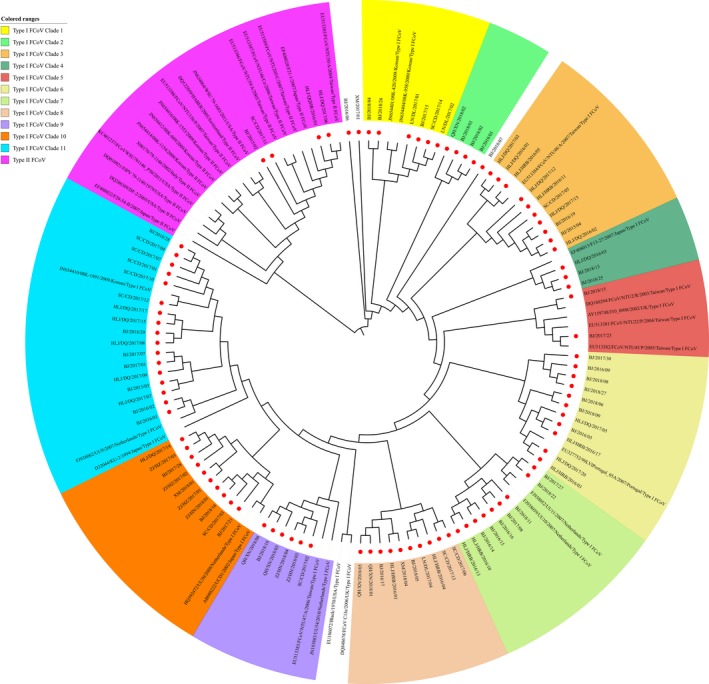

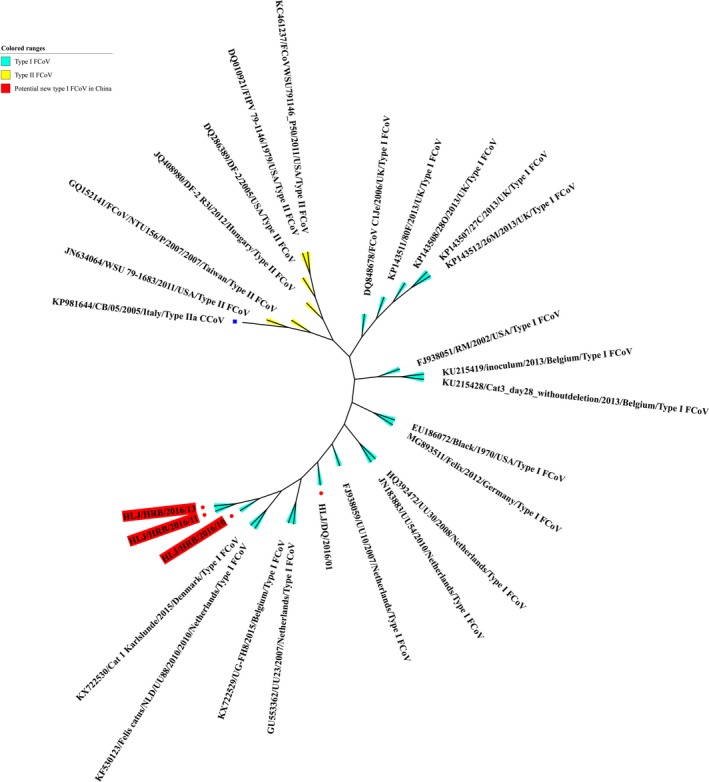

To trace the evolution of the type I and type II FCoV strains identified in China, the partial S genes of the FCoV strains from different geographical locations in China and the rest of the world were used to construct a phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic tree generated was composed of two groups: type I FCoVs and type II FCoVs. Of the 95 FCoV strains identified in China, 91 strains fell into the type I FCoV group, forming 11 clusters in the partial S gene‐based phylogenetic tree; four strains belonged to the type II FCoV group, exhibiting close relationships with the type II FCoV reference strains from Asian countries (Figure 2). In our study, the nearly complete genomes of four type I FCoV strains, HLJ/DQ/2016/01 (GenBank accession no. KY292377, 29,303 bp), HLJ/HRB/2016/10 (GenBank accession no. KY566209, 29,440 bp), HLJ/HRB/2016/11 (GenBank accession no. KY566210, 29,297 bp), and HLJ/HRB/2016/13 (GenBank accession no. KY566211, 29,337 bp), were obtained. The genome sequences of the four strains included all ORFs of FCoV. The four strains were identified in the FIP‐suspected cats. The phylogenetic analysis indicated that the HLJ/HRB/2016/10, HLJ/HRB/2016/11, and HLJ/HRB/2016/13 strains formed one cluster of a potentially new type I FCoV when compared with the type I and type II FCoV reference strains, and the strain HLJ/DQ/2016/01 formed another clade; the three strains HLJ/HRB/2016/10, HLJ/HRB/2016/11, and HLJ/HRB/2016/13 showed the highest phylogenetic relationship with the Cat 1 Karlslunde reference strain from Denmark (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analyses of FCoV strains on the basis of the partial S gene (168 bp). Red spot diagram represents the 95 FCoV strains identified in our study [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analyses of four FCoV strains identified in our study according to their nearly complete genome sequences. Red spot diagram represents the 4 FCoV strains identified in our study. The type IIa CCoV strain CB/05 (GenBank accession no. KP981644) was used as an outgroup (Blue square diagram) [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

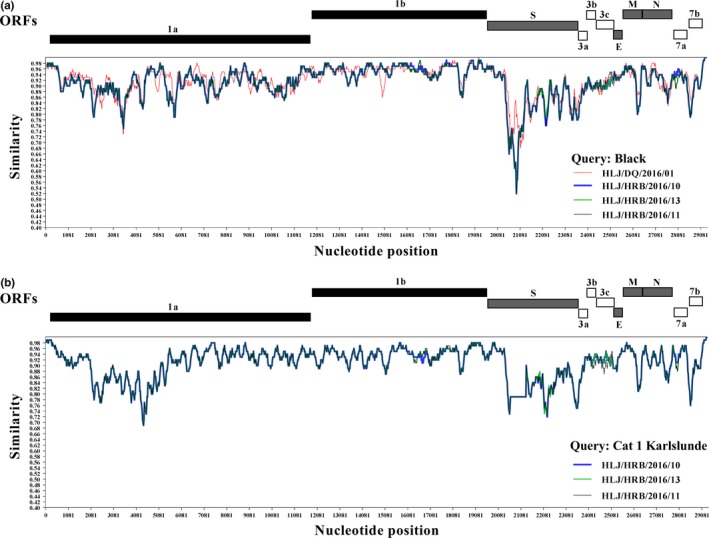

The genomic similarity analysis revealed that the four type I FCoV strains with the nearly complete genomes identified in our study were clearly distinct from the classical Black strain of the type I FCoV from USA at the part of the S gene (Figure 4a). Of the four identified type I FCoV strains, the genome of the HLJ/DQ/2016/01 strain exhibited the divergence when compared with the HLJ/HRB/2016/10, HLJ/HRB/2016/11, and HLJ/HRB/2016/13 strains. This result was in line with the nearly complete genomes‐based phylogenetic tree (Figure 3). The HLJ/HRB/2016/10, HLJ/HRB/2016/11 and HLJ/HRB/2016/13 strains exhibited the obvious difference at the part of the S gene, 3′ end of the ORF1a gene, M gene, and ORF7b gene when compared with the Cat 1 Karlslunde strain of the type I FCoV from Denmark (Figure 4b). Moreover, analysis of the genomic comparison revealed that the three strains HLJ/HRB/2016/10, HLJ/HRB/2016/11, and HLJ/HRB/2016/13 showed amino acids similarity of 94.7% (percentage of divergence: 5.3%) when compared with the classical Black strain of the type I FCoV; the amino acids similarity of 95.1% (percentage of divergence: 4.9%) were observed between the three strains and the Cat 1 Karlslunde reference strain of the type I FCoV.

Figure 4.

Genomic similarity analysis of the type I FCoV strains identified in our study. (a) Genomic similarity plot of the four type I FCoV strains HLJ/HRB/2016/10, HLJ/HRB/2016/11, HLJ/HRB/2016/13, HLJ/DQ/2016/01, and the classic Black strain. In Figure 4a, the Black strain was designated as query strain (value=1). (b) Genomic similarity plot of the three type I FCoV strains HLJ/HRB/2016/10, HLJ/HRB/2016/11, HLJ/HRB/2016/13 and Cat 1 Karlslunde type I FCoV strain. In Figure 4b, the Cat 1 Karlslunde strain was designated as query strain (value = 1). The similarity plot was constructed using the two‐parameter (Kimura) distance model with a sliding window of 200 bp and step size of 20 bp. A similarity of 1.0 indicates regions that share 100% nucleotide identity. The vertical and horizontal axes indicated the nucleotide similarity percent and nucleotide position (bp) in the graph, respectively [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

In China, FIP is a serious and emerging problem in domestic cats. Little information regarding the epidemiology of FCoV is available in China. In our study, 115 samples of ascitic fluid from FIP‐suspected diseased cats and 54 fecal samples from clinically healthy cats were subjected to detection and phylogenetic analysis of FCoV. A total of 126 (74.6%, 126/169) samples were positive for FCoV. Of the 126 FCoV positive samples, the positive rate of FCoV in the FIP‐suspected cats was 75.7% (87/115), which was higher than in Korea (19.3%) and Turkey (37.3%) (An et al., 2011; Tekelioglu et al., 2015). The FCoV positive rate of cats from south China (80.0%) was higher than that of north China (73.1%). Several studies have reported that age, breed, sex, and a multi‐cat environment are associated with FCoV infection and development of FIP (Addie et al., 2009; Bell, Malik, & Norris, 2006; Sharif et al., 2009; Worthing et al., 2012). In the present study, FCoV infection was significantly associated with living environment and age, which is in line with previous studies (Addie et al., 2009; Drechsler, Alcaraz, Bossong, Collisson, & Diniz, 2011; Tekelioglu et al., 2015); the positive rate of FCoV in a multi‐cat environment was higher than that in single cat households. These data suggest that a multi‐cat environment confers a high risk for FCoV infection and development of FIP in China.

In our study, the prevalence of FCoV was not significantly associated with sex, which is in agreement with several studies (Bell et al., 2006; Sharif et al., 2009; Taharaguchi, Soma, & Hara, 2012). On the contrary, several studies have shown that FCoV infection appeared to be significantly correlated with the male sex (Pesteanu‐Somogyi, Radzai, & Pressler, 2006; Worthing et al., 2012). However, Tekelioglu et al. (2015) reported that the seroprevalence of FCoV was not associated with sex. In the current study, FCoV infection was also not associated with the breed of cat, which is in line with a study in Turkey (Tekelioglu et al., 2015). In contrast, several studies have reported that FCoV infection exhibited a significant association with breed: purebred cats appear to be more susceptible to FCoV infection (Foley & Pedersen, 1996; Kiss, Kecskeméti, Tanyi, Klingeborn, & Belák, 2000). In Australia, FCoV infection occurred at a significantly higher prevalence in British Shorthairs, Cornish Rex and Burmese cats than in Siamese, Persian, Domestic Shorthairs, and Bengal cats (Bell et al., 2006). In Malaysia, the FCoV infection rate in Persian purebred cats (96.0%) was higher than that in the mixed‐breed cats (70.0%) (Sharif et al., 2009). In Japan, the prevalence of antibodies against FCoV in purebred cats (66.7%) was higher than that in random breeds (31.2%) (Taharaguchi et al., 2012). In our study, FCoV infection was significantly associated with young cats (aged <6 months). Other studies have reported that cats of ages ranging from 3 to 11 months exhibit a higher FCoV prevalence than those of other ages (Bell et al., 2006; Pedersen, 2009; Taharaguchi et al., 2012). However, FCoV infection in Australia and Malaysia was reported not to be associated with age (Bell et al., 2006; Sharif et al., 2009). These data suggest that the biological reason underlying the age/sex/breed‐associated susceptibility and resistance to FCoV remains unknown and is associated with different lifestyles and FCoV exposure in different studies.

The FCoVs are classified into two distinct serotypes, type I FCoV and type II FCoV, according to their serological properties. In our study, the partial S genes of 95 samples were successfully sequenced, out of the 126 FCoV positive samples. Of the 126 FCoV positive samples, the partial S genes of 31 samples were not obtained due to the low viral load in samples or the potential mismatching between primers and templates. Most of the FCoV strains identified in our study belonged to type I FCoV (95.8%, 91/95) according to the phylogenetic analysis of the partial S gene; only four FCoV strains (4.2%, 4/95) were allocated to type II FCoV. In our study, the prevalence of type I FCoV in the FIP‐suspected cats was higher than that of type I FCoV in Taiwan (89.0%, p > 0.05) and Korea (54.5%, p < 0.01) (An et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2009). These data suggested that type I FCoV was more prevalent in cats in China. Further studies should be conducted to understand the effect of the high prevalence of type I FCoV strains on the development of FIP in China. Co‐infection with type I and II FCoVs has been reported in cats in many countries (Benetka et al., 2004; Hohdatsu, Okada, Ishizuka, Yamada, & Koyama, 1992; Kummrow et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2009). Double homologous recombination between type I FCoV and CCoV leads to the emergence of type II FCoV (An et al., 2011; Decaro & Buonavoglia, 2008; Haijema et al., 2007; Herrewegh et al., 1998; Lin et al., 2013; Lorusso et al., 2008; Terada et al., 2014). In our study, co‐infection of the type I and II FCoVs was not observed in FIP‐suspected or healthy cats. Meanwhile, the type II FCoV strains were only identified in FIP‐suspected samples, not in healthy cats. These data demonstrated that FCoV exhibited mainly a single serotype infection in cats in China, which may be attributed to a lack of vaccine immunization against FCoV or co‐breeding of dogs and cats in China.

In our study, sequence analysis of the partial S gene indicated that the three type I FCoV strains, BJ/2017/27 from FIP‐suspected cat, BJ/2018/22 from FIP‐suspected cat, and XM/2018/04 from clinically healthy cat, exhibited a six‐nucleotide deletion (C4035AGCTC4040) when compared with other type I FCoV strains identified in our study and type I FCoV reference strains. Further analysis indicated that the six‐nucleotide deletion (C4035AGCTC4040) in the three type I FCoV strains was not reported in the current GenBank database, according to the nucleotide BLAST search tool. The information from the limited samples suggested that the three FCoV strains with the six unique nucleotide deletions may be one of the characteristics of Chinese regional type I FCoV strains. The partial S gene‐based phylogenetic tree revealed the genetic diversity of the type I FCoV strains identified: the type I FCoV strains collected from the same region of China showed genetic diversity from each other. In contrast, the type II FCoV strains identified in our study formed one clade in the partial S gene‐based phylogenetic tree, exhibiting a close relationship with type II FCoV strains from Taiwan and Japan. In our study, analysis of the phylogenetic tree and genome similarity indicated that the three FCoV strains with the nearly complete genome (HLJ/HRB/2016/10, HLJ/HRB/2016/11, and HLJ/HRB/2016/13) formed a potentially new type I FCoV cluster, and differed genetically from the classical Black strain of the type I FCoV from USA and the Cat 1 Karlslunde strain of the type I FCoV from Denmark. These data suggested that the high infection rates of the type I FCoV has led to the high seroprevalence of type I FCoV in the cat population in China. The high variability of the type I FCoV strains in our study may be attributed to long‐term interactions between the type I FCoV strains and their hosts. Those strains in the potential new type I FCoV cluster and those with the six unique nucleotide deletions (C4035AGCTC4040) also support the above speculation.

The current study is the first to reveal the circulation and genetic diversity of type I and II FCoVs from clinically healthy and FIP‐suspected cats in China. The type I and type II FCoV strains co‐circulate in the FIP‐affected cats in China. Type I FCoV strains exhibited high prevalence and genetic diversity in both FIP‐affected and clinically healthy cats. A multi‐cat environment and cats younger than 6 months were associated with a significantly higher FIP occurrence. The resulting data increased our understanding of the genetic evolution of FCoV strains in China, and provide valuable information for further studies of FCoV.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for statistical analysis provided by Dr. Ming Fang (College of Life Science and Technology, Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University). This work is supported by the Outstanding Youth Science Foundation of Heilongjiang province in China (grant no. JC2017007), the Heilongjiang Province Postdoctoral Science Foundation in China (LBH‐Q16188), Innovation Team Foundation of Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University (TDJH201804).

Li C, Liu Q, Kong F, et al. Circulation and genetic diversity of Feline coronavirus type I and II from clinically healthy and FIP‐suspected cats in China. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2019;66:763–775. 10.1111/tbed.13081

REFERENCES

- Addie, D. , Belák, S. , Boucraut‐Baralon, C. , Egberink, H. , Frymus, T. , Gruffydd‐Jones, T. , … Horzinek, M. C. (2009). Feline infectious peritonitis. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 11(7), 3594–3604. 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer, A. , Siti‐Suri, A. , Abdul‐Rahman, O. , Mohd, H. B. , Faruku, B. , Saeed, S. , & Tengku Azmi, T. I. (2012). Isolation and molecular characterization of type I and type II feline coronavirus in Malaysia. Virology Journal, 9, 278 10.1186/1743-422X-9-278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An, D. J. , Jeoung, H. Y. , Jeong, W. , Park, J. Y. , Lee, M. H. , & Park, B. K. (2011). Prevalence of Korean cats with natural feline coronavirus infections. Virology Journal, 8, 455 10.1186/1743-422X-8-455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E. T. , Malik, R. , & Norris, J. M. (2006). The relationship between the feline coronavirus antibody titre and the age, breed, gender and health status of Australian cats. Australian Veterinary Journal, 84(1–2), 2–7. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2006.tb13114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benetka, V. , Kübber‐Heiss, A. , Kolodziejek, J. , Nowotny, N. , Hofmann‐Parisot, M. , & Möstl, K. (2004). Prevalence of feline coronavirus types I and II in cats with histopathologically verified feline infectious peritonitis. Veterinary Microbiology, 99(1), 31–42. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaro, N. , & Buonavoglia, C. (2008). An update on canine coronaviruses: Viral evolution and pathobiology. Veterinary Microbiology, 132(3–4), 221–234. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsler, Y. , Alcaraz, A. , Bossong, F. J. , Collisson, E. W. , & Diniz, P. P. (2011). Feline coronavirus in multicat environments. The Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice, 41(6), 1133–1169. 10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J. E. , & Pedersen, N. C. (1996). The inheritance of susceptibility to feline infectious peritonitis virus in purebred catteries. Feline Practice, 24(1), 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Haijema, B. J. , Rottier, P. J. , & de Groot, R. J. (2007). Feline coronaviruses: A tale of two‐faced types In Academic C. (Ed.), Coronaviruses Molecular and Cellular Biology, Thiel V (pp. 183–204). Norfolk, UK: Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herrewegh, A. A. , de Groot, R. J. , Cepica, A. , Egberink, H. F. , Horzinek, M. C. , & Rottier, P. J. (1995). Detection of feline coronavirus RNA in feces, tissues, and body fluids of naturally infected cats by reverse transcriptase PCR. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 33(3), 684–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrewegh, A. A. , Smeenk, I. , Horzinek, M. C. , Rottier, P. J. , & de Groot, R. J. (1998). Feline coronavirus type II strains 79‐1683 and 79‐1146 originate from a double recombination between feline coronavirus type I and canine coronavirus. Journal of Virology, 72(5), 4508–4514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohdatsu, T. , Okada, S. , Ishizuka, Y. , Yamada, H. , & Koyama, H. (1992). The prevalence of types I and II feline coronavirus infections in cats. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 54(3), 557–562. 10.1292/jvms.54.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, I. , Kecskeméti, S. , Tanyi, J. , Klingeborn, B. , & Belák, S. (2000). Preliminary studies on feline coronavirus distribution in naturally and experimentally infected cats. Research in Veterinary Science, 68(3), 237–242. 10.1053/rvsc.1999.0368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummrow, M. , Meli, M. L. , Haessig, M. , Goenczi, E. , Poland, A. , Pedersen, N. C. , … Lutz, H. (2005). Feline coronavirus serotypes 1 and 2: Seroprevalence and association with disease in Switzerland. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology, 12(10), 1209–1215. 10.1128/CDLI.12.10.1209-1215.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic, I. , & Bork, P. (2007). Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics, 23(1), 127–128. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. N. , Chang, R. Y. , Su, B. L. , & Chueh, L. L. (2013). Full genome analysis of a novel type II feline coronavirus NTU156. Virus Genes, 46(2), 316–322. 10.1007/s11262-012-0864-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. N. , Su, B. L. , Wang, C. H. , Hsieh, M. W. , Chueh, T. J. , & Chueh, L. L. (2009). Genetic diversity and correlation with feline infectious peritonitis of feline coronavirus type I and II: A 5‐year study in Taiwan. Veterinary Microbiology, 136(3–4), 233–239. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lole, K. S. , Bollinger, R. C. , Paranjape, R. S. , Gadkari, D. , Kulkarni, S. S. , Novak, N. G. , … Ray, S. C. (1999). Full‐length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C‐infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. Journal of Virology, 73(1), 152–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso, A. , Decaro, N. , Schellen, P. , Rottier, P. J. , Buonavoglia, C. , Haijema, B. J. , & de Groot, R. J. (2008). Gain, preservation, and loss of a group 1a coronavirus accessory glycoprotein. Journal of Virology, 82(20), 10312–10317. 10.1128/JVI.01031-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marthaler, D. , Jiang, Y. , Otterson, T. , Goyal, S. , Rossow, K. , & Collins, J. (2013). Complete genome sequence of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain USA/Colorado/2013 from the United States. Genome Announcements, 1(4), pii, e00555–13. 10.1128/genomeA.00555-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrrha, L. W. , Silva, F. M. , Peternelli, E. F. , Junior, A. S. , Resende, M. , & de Almeida, M. R. (2011). The paradox of feline coronavirus pathogenesis: A review. Advances in Virology, 2011, 109849 10.1155/2011/109849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, N. C. (2009). A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection: 1963‐2008. Journal of Feline Medicine Surgery, 11(4), 225–258. 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesteanu‐Somogyi, L. D. , Radzai, C. , & Pressler, B. M. (2006). Prevalence of feline infectious peritonitis in specific cat breeds. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 8(1), 1–5. 10.1016/j.jfms.2005.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, S. , Arshad, S. S. , Hair‐Bejo, M. , Omar, A. R. , Zeenathul, N. A. , Fong, L. S. , … Isa, M. K. (2010). Descriptive distribution and phylogenetic analysis of feline infectious peritonitis virus isolates of Malaysia. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 52, 1 10.1186/1751-0147-52-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, S. , Arshad, S. S. , Hair‐Bejo, M. , Omar, A. R. , Zeenathul, N. A. , & Hafidz, M. A. (2009). Prevalence of feline coronavirus in two cat populations in Malaysia. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 11(12), 1031–1034. 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taharaguchi, S. , Soma, T. , & Hara, M. (2012). Prevalence of feline coronavirus antibodies in Japanese domestic cats during the past decade. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 74(10), 1355–1358. 10.1292/jvms.11-0577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K. , Stecher, G. , Peterson, D. , Filipski, A. , & Kumar, S. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular Bioloty and . Evolution, 30(12), 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekelioglu, B. K. , Berriatua, E. , Turan, N. , Helps, C. R. , Kocak, M. , & Yilmaz, H. (2015). A retrospective clinical and epidemiological study on feline coronavirus (FCoV) in cats in Istanbul, Turkey. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 119(1–2), 41–47. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekes, G. , & Thiel, H. J. (2016). Feline Coronaviruses: Pathogenesis of feline infectious peritonitis. Advances in Virus Research, 96, 193–218. 10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada, Y. , Matsui, N. , Noguchi, K. , Kuwata, R. , Shimoda, H. , Soma, T. , … Maeda, K. (2014). Emergence of pathogenic coronaviruses in cats by homologous recombination between feline and canine coronaviruses. PLoS One, 9(9), e106534 10.1371/journal.pone.0106534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. D. , Gibson, T. J. , Plewniak, F. , Jeanmougin, F. , & Higgins, D. G. (1997). The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research, 25(24), 4876–4882. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E. , Guo, D. , Li, C. , Wei, S. , Wang, Z. , Liu, Q. , … Sun, D. (2016). Molecular characterization of the ORF3 and S1 genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus non S‐indel strains in seven regions of China, 2015. PLoS One, 11(8), e0160561 10.1371/journal.pone.0160561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, L. G. , & Griesemer, R. A. (1966). Feline infectious peritonitis. Pathologia Veterinaria, 3(3), 255–270. 10.1177/030098586600300309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthing, K. A. , Wigney, D. I. , Dhand, N. K. , Fawcett, A. , McDonagh, P. , Malik, R. , & Norris, J. M. (2012). Risk factors for feline infectious peritonitis in Australian cats. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 14(6), 405–412. 10.1177/1098612X12441875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials