Abstract

Background

Mindfulness-based interventions, Tai Chi/Qigong, and Yoga (defined here as meditative cancer interventions [MCIs]) have demonstrated small to medium effects on psychosocial outcomes in female breast cancer patients. However, no summary exists of how effective these interventions are for men with cancer.

Purpose

A meta-analysis was performed to determine the effectiveness of MCIs on psychosocial outcomes (e.g., quality of life, depression, and posttraumatic growth) for men with cancer.

Methods

A literature search yielded 17 randomized controlled trials (N = 666) meeting study inclusion criteria. The authors were contacted to request data for male participants in the study when not reported.

Results

With the removal of one outlier, there was a small effect found in favor of MCIs across all psychosocial outcomes immediately postintervention (g = .23, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.02 to 0.44). Studies using a usual care control arm demonstrated a small effect in favor of MCIs (g = .26, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.42). However, there was insufficient evidence of a superior effect for MCIs when compared to an active control group, including attention control. Few studies examined both short-term and long-term outcomes.

Conclusions

There is evidence for MCIs improving psychosocial outcomes in male cancer survivors. However, this effect is not demonstrated when limited to studies that used active controls. The effect size found in this meta-analysis is smaller than those reported in MCI studies of mixed gender and female cancer patient populations. More rigorously designed randomized trials are needed that include active control groups, which control for attention, and long-term follow-up. There may be unique challenges for addressing the psychosocial needs of male cancer patients that future interventions should consider.

Keywords: Men, Cancer, Mindfulness-based interventions, Survivorship

Compared to those on a wait-list, men living with cancer show modest improvement in psychological and social well-being after participating in randomized trials of mindfulness, tai chi, or yoga interventions.

Introduction

Cancer, the second leading cause of death in the USA, is a significant and extensive public health problem [1, 2]. The probability of a lifetime diagnosis of cancer is close to 40% for those living in the USA [2]. There are approximately 1.6 million new cancer cases and nearly 600,000 cancer-related deaths annually in the USA alone [2]. Despite relatively high global and U.S. cancer mortality rates, and the persistence of racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening and treatment outcomes, people are living longer than ever before with cancer [3]. Given that the risk of receiving a cancer diagnosis increases with age, survivorship is often marked by the challenges of managing the late and long-term effects of treatment along with age-related morbidities. It is estimated that there are currently 9 million survivors over the age of 65 in the USA [4], a number that is projected to increase to more than 19 million by the year 2040 [5, 6].

Cancer survivorship, especially for an aging population, entails unique psychosocial stressors [6, 7]. Even treatment completion does not mark the end of the cancer experience as there are often unaddressed psychosocial stressors that persist, including shame and social isolation [8, 9]. These stressors negatively impact well-being through an increased occurrence of psychological conditions, most notably higher rates of depression and anxiety [10, 11], adjustment difficulties [12], fear of recurrence [13], and relationship challenges [6].

Over the past few decades, there has been increasing interest in mindfulness training to aid individuals with cancer-related psychosocial difficulties [14–16]. There are two broad categories that these mindfulness interventions fall into. The first, mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) [17] include group-based formal training in mindfulness, especially mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). These MBIs are the most common to cancer care populations and have a common origin with Kabat-Zinn’s [18] protocol developed originally for hospital patients with complex physical and psychological needs [19]. The second fall into the “meditative movement” category and include Yoga and Tai Chi/Qigong, both ancient practices [20]. While there is heterogeneity in MBI and meditative movement treatment protocols [21], they share a focus on breathing, promotion of a cleared or calm state of mind, facilitation of present-focused awareness [17, 22], and a goal of deep states of relaxation [20].

In cancer care, both MBIs and meditative movement interventions have been increasingly used as adjunctive treatments [14–16, 23]. Recent reviews of MBSR interventions found medium effect sizes for anxiety symptoms and small effects for depressive symptoms in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for women with breast cancer [24]. Similarly, research on both Tai Chi/Qigong and Yoga, predominantly in breast cancer survivors, demonstrate improved psychosocial outcomes for depression, anxiety, and distress [25–27]. Given similar proposed mechanisms of action in those with cancer, both MBIs and meditative movement interventions can be considered part of a larger category, which we will refer to as meditative cancer interventions (MCI).

One significant shortcoming of the MCI literature in cancer survivors is that evidence regarding efficacy in men is largely absent. For example, despite cancer mortality being higher among men than women, most of the MCI clinical trials are comprised primarily or exclusively of female populations, especially among those with breast cancer [24, 28]. For those trials with a variety of cancer types, men typically comprise less than a quarter of the participants [26]. There have been several sex-specific MCI randomized trials with prostate cancer populations, although these have only been conducted in the past few years and little summary data exists of their outcomes.

That men are underrepresented in MCI trials is not surprising. For one, men are less likely than women to engage in mindfulness practices overall in the USA [29]. Given that men, along with racial and ethnic minorities, are less likely to engage in these practices, they are considered to be underserved, vulnerable, and “priority populations” for future study of such interventions [30]. Similarly, men are less likely than women to access supportive cancer care in general [31] and may also be underreporting the emotional distress associated with the physical side effects of cancer treatments [9, 32]. Thus, there is a need to understand more about the evidence base for MCIs for men with cancer [33] in order to successfully adapt these treatments to the rapidly growing population of male cancer populations [34]. Therefore, the goal of the present meta-analysis was to quantitatively review and summarize the evidence for male cancer patient psychosocial outcomes at short or longer-term follow-up in MCIs.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Studies that matched the following eligibility criteria were included: (a) published in the English language, (b) cancer population (any stage, including pretreatment, current treatment, and posttreatment), (c) RCT, (d) at least 10% of the study population was male, (e) published in a peer-reviewed journal as of December 2017, (f) study included an intervention that fits the definition of MCI (e.g., MBSR, MBCT, Tai Chi/Qigong, and Yoga), and (g) psychosocial outcomes, defined in this study as patient-reported outcomes that capture domains related to psychological and social functioning (e.g., anxiety, depression, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and posttraumatic growth). Studies that only had patient-reported outcomes related to physical health (e.g., fatigue, pain, and sleep) were excluded. The search was restricted to RCTs in order to include only the highest-quality evidence for quantifying the effect of MCIs.

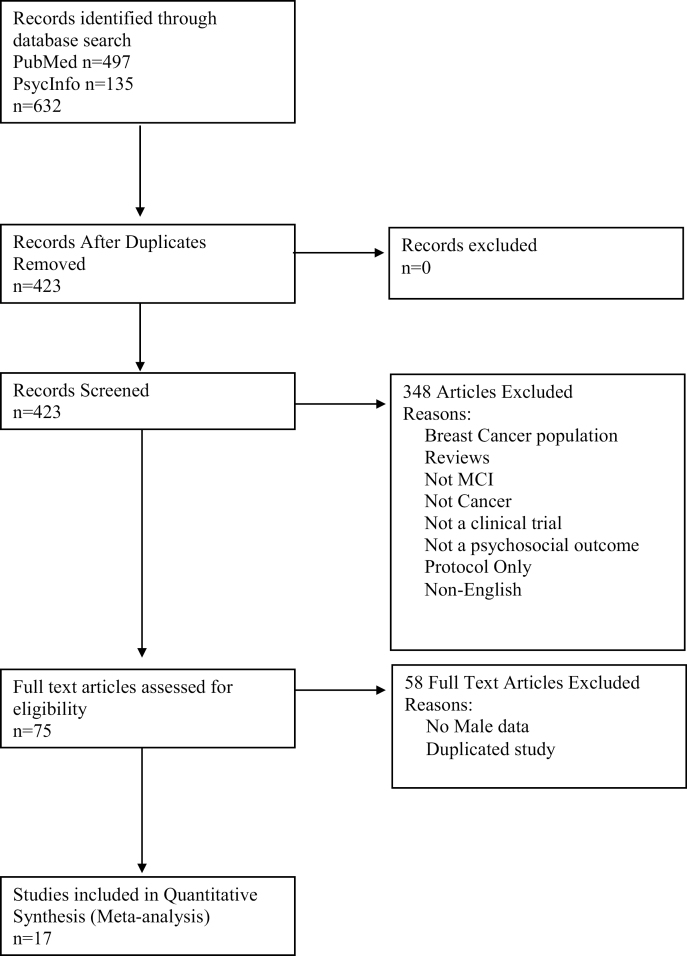

The literature search was completed in December 2017 and included psychological (PsychINFO) and medical (MEDLINE) databases using the terms (Qigong OR Qi Gong OR Tai Chi OR TCC OR MQG) AND (Cancer) AND (RCT or Randomized or Randomised) (MBSR OR MBCT OR Mindfulness OR Meditation) AND (Cancer) AND (RCT or Randomized or Randomised) AND (Yoga) AND (Cancer) AND (RCT or Randomized or Randomised). If primary articles did not report outcomes separately for male participants, corresponding authors were contacted to request these data. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines were used for reporting for study inclusion [35].

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by three coders (C.G.F. and two students trained in psychology research methods and experienced with coding) independently using a data extraction sheet (Supplementary Appendix 1). The extracted data included bibliographic information, study information, participant demographics at baseline, details on treatment and control groups, psychological outcome measures, and quality assessment coding using a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Assessment tool customized for the studies included in the current meta-analysis [36]. The risk of bias was assessed as low, unclear, or high across 12 domains. Studies that were at high or unclear risk in at least half of these domains were considered to be at a “high-risk of bias.” An interrater reliability analysis using Cohen’s Kappa statistic was performed to determine consistency among raters. Conflicts were discussed among the three raters to achieve consensus.

Statistical Methods

A meta-analysis of eligible studies was performed to summarize the outcomes of interest for intervention groups compared to controls. Effect sizes were calculated using Hedges’ standardized mean difference (Hedges’ g). Hedges’ g was chosen as the effect size calculation instead of Cohen’s d as it is a more conservative estimate of effect, especially with smaller samples [37].

The formula for the effect size was conducted using the mean and standard deviation from the posttreatment data only. The Cochrane Handbook, a standard for best practices in the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, advises against the use of meta-analysis of change scores in the absence of using a meta-regression approach [38]. Given that only randomized studies were used in the analysis, there were only minimal baseline differences between the intervention and control groups.

Given the heterogeneity of study type, a random-effects model, rather than a fixed-effects model, was used for the meta-analysis on the assumption that effects would differ among studies [38]. Most studies included multiple psychosocial measures from the same study, raising the issue of dependence arising from the use of multiple outcomes [39]. Studies that included multiple measures of a domain, depending on the outcomes, may be inappropriately underweighted or overweighted as multiple outcomes are not independent information. Borenstein’s conservative approach was used to calculate a synthetic summary variable which assumes a .5 correlation between the outcome variables and corrects for the number of outcomes from each study [37]. The overall psychosocial summary variable created for multiple outcomes in a study included studies that used multiple psychosocial domains (e.g., HRQOL, negative mental health [NMH], and positive mental health [PMH]). Although these domains are related, they are conceptually distinct. PMH and NMH are sufficiently distinct to be routinely considered as independent unipolar dimensions in much of the literature [40]. While measures of mental health (both positive and negative) constitute a portion of HRQOL, itself a multidimensional construct, they are sufficiently distinct to be understood as separate domains [41]. Although these three domains are necessarily correlated, given their conceptual and statistical independence, we believed it was possible to summarize an overall effect for these outcomes.

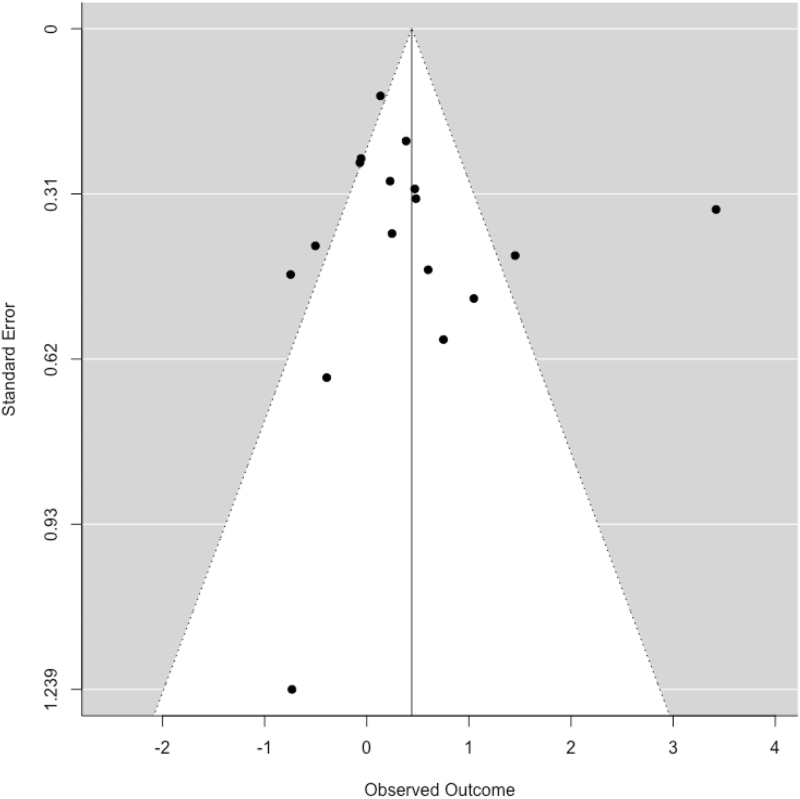

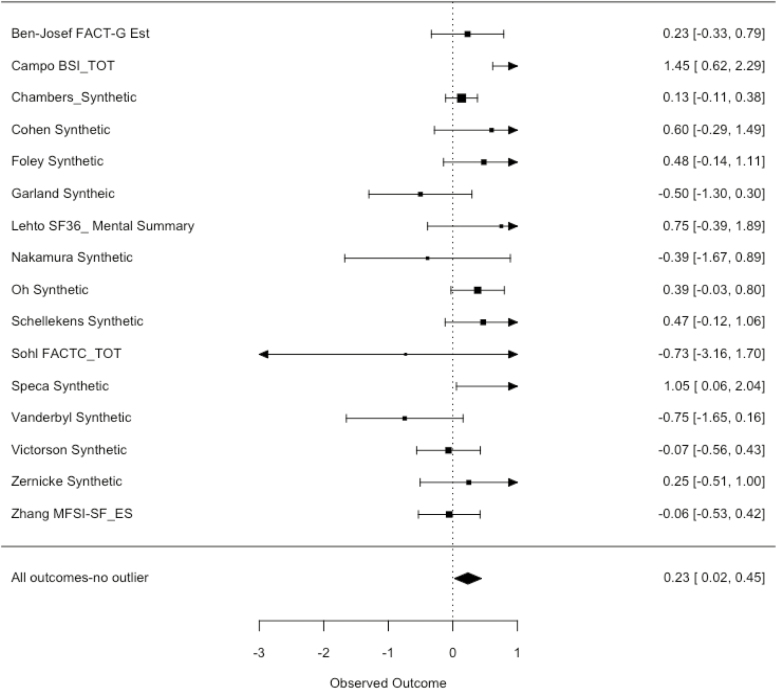

Statistical heterogeneity, an indication of inconsistent results across studies, was assessed using two related statistics, Q and I^2. Studies were characterized as possibly having heterogeneity using the interpretation guide provided in the Cochrane Handbook for I^2, which is expressed in percentages: 0%–30% might not be important heterogeneity, 30%–50% is considered to be moderate heterogeneity, and 50% and above as substantial heterogeneity. To assess for outliers within the meta-analysis, visual inspection of the forest plots, as well as a formal statistical test identified by Viechtbauer for use with meta-analyses (DFBETAs), was used (Figs. 1 and 2) [42]. All study analyses were run in the Metafor package for R statistical software [43].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA search flowchart.

Fig. 2.

Funnel plot for visual inspection of publication bias (n = 17).

Results

Literature Search

Figure 1 summarizes the flow of the search process corresponding to PRISMA guidelines for meta-analytic searches. A total of 17 studies were included in the final quantitative meta-analysis [44–60]. Complete psychosocial data for the male participants was available in the published articles or obtained from study authors for 13 of the 17 articles included in the present analysis. Four authors (Foley, Oh, Lehto, and Zhang) did not respond to requests for data on male participants [49, 51, 53, 60]. For these studies, male data were assumed to reflect the published findings for both men and women. This assumption was made after obtaining a “male data only” ratio, which compared the cumulative effect sizes found for studies that provided data on men alone in the study and compared these effect sizes to the effect found by the same studies, including the full sample of both men and women. We found that there was no appreciable difference between these two calculations (g = .58, 95% CI −0.34 to 1.5, p = .2 for the published data that pooled men and women together, and g = .61, 95% CI −0.32 to 1.5, p = .2 for the author-supplied data of male-only data from the same studies) suggesting that the assumption to include these four studies’ published data in the final analysis is reasonable for the purposes of the present analysis. Sensitivity analyses were conducted without including these four studies, which did not significantly change the reported results.

Participant Characteristics

A total of 666 male cancer patients from 17 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Demographic information collected included age, race, marital status, employment, education level, cancer stage, and cancer type. Results are described in Table 1. The average age of participants was 61.9 years (standard deviation 11.1). Of those (n = 12 studies) reporting race/ethnicity, 73% of the sample was non-Hispanic white. For studies outside of China and Taiwan (n = 10), 87% of the participants were non-Hispanic white. Overall, 80.5% of the men were married and 45% were employed. Of those reporting education level (n = 9 studies), the majority of the sample was college educated (62%). There was a variety of cancer types represented, with more than three cancer types represented in five studies, followed by exclusively prostate and lung cancer populations in four studies.

Table 1.

Demographic information: limited to information supplied by study authors on demographics of male participants

| Category | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (standard deviation) | 61.19 (11.14) | |

| Total | 666 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | White | 433 | 72 |

| Non-White | 168 | 28 | |

| Total | 601 | ||

| Relationship status | Married | 481 | 80 |

| Nonmarried | 120 | 20 | |

| Total | 601 | ||

| Employment | Employed | 196 | 46 |

| Retired or not working | 231 | 54 | |

| Total | 427 | ||

| Education | HS or less | 164 | 38 |

| College of more | 268 | 62 | |

| Total | 432 | ||

| Cancer stage | 1 or 2 | 68 | 38 |

| 3 or 4 | 111 | 59 | |

| Total | 179 |

HS high school.

Study Designs

Supplementary Table 1 displays the relevant characteristics of the selected studies. Descriptively, the MCIs varied widely both within and between the three major intervention categories (mindfulness based [MB], Tai Chi/Qigong (TCQ), and Yoga). Most interventions were held in-person and in a group-based setting (n = 11), although a few took place at patient’s home (n = 2) by phone or online (n = 2) or in a hospital setting (n = 1). Intervention length ranged from as few as three sessions to as many as two sessions per week for 12 weeks, with session length ranging from 20 to 150 min. Control groups were categorized as either usual care (which included waiting lists) or active controls (e.g., exercise, education groups, and attention controls). Inclusion criteria varied widely with most studies having minimal criteria beyond a cancer diagnosis.

Risk of Bias

Studies were assessed for their risk of bias using the NIH Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies (Supplementary Appendix 1). The interrater reliability for the raters was found to have substantial agreement with Kappa = 0.84 (p < .001), 95% CI (0.72, 0.94), for the full set of quality coding. All disagreements were resolved via meetings of the three coders to achieve consensus. Only one study, Ben-Josef, was flagged as having 50% of the bias categories as high or unclear (Table 2). The most common category that flagged for a high risk of bias was high attrition, defined as greater than 20% of the intervention or control group. The majority of the studies (12 of 17) demonstrated this risk. The other categories in which more than half of the studies demonstrated the potential for bias were in measuring high adherence to the intervention, having adequate power to detect a small effect, and conducting an intention-to-treat analysis to account for study dropouts.

Table 2.

Risk of study bias

| Random | Tx allocation | Blind assessor | Baseline similar | Low dropout | Diff. dropout | High adherence | Background Tx | Valid measures | Power | Prespecified | ITT Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ben-Josef | Yes | Yes | CD | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Campo | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Chambers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chuang | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Cohen | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | No | NR | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Foley | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Garland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | CD | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Lehto | Yes | Yes | CD | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | CD | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Nakamura | Yes | Yes | NR | CD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes |

| Oh | Yes | Yes | CD | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Schellekens | Yes | Yes | CD | Yes | No | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Sohl | Yes | Yes | NR | CD | No | Yes | Yes | CD | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Speca | Yes | Yes | CD | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Vanderbyl | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NR |

| Victorson | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Zernicke | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zhang | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | CD | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

CD, unclear risk of study bias; ITT, Intention-to-treat; No, high risk of study bias; NR, Not reported; Tx, Treatment;Yes, low risk of study bias.

Publication bias was assessed via visual inspection of the funnel plot of the studies and carried out by an Eggers’ regression test of plot asymmetry (Fig. 2). Aside from one outlier, the funnel test appeared to be appropriately asymmetrical and the regression test had an insignificant p-value (p = .60) and, thus, no publication bias seemed to exist in the current sample [61].

Outcome Measures

The psychosocial outcomes measured covered a diverse range of psychological and social outcomes and, therefore, were broadly grouped into three categories: HRQoL, NMH, and PMH (c.f. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for a complete list and summary of included measures). Because of the lack of uniformity in outcome measurements, even within individual constructs, there was greater statistical power to detect differences between groups when these were pooled together rather than analyzed at the construct or individual measure level. The meta-analysis results below considered these three groups as moderators of the overall effects found.

Effect of MCIs on Combined Psychosocial Outcomes

Table 3 provides a statistical summary found across all outcomes as well as within subgroups. The 17 studies included 43 separate psychosocial outcomes measures at short- or longer-term follow-up. When multiple measures were used to assess one of the three outcome measure categories, a variable was created for average effect size using the weighted variance formula suggested by Borenstein et al. [37]. For the calculation of the overall effect, measures for which a lower score indicates better health (e.g., NMH measures) were multiplied by −1 to compare all outcomes in the same direction such that higher scores were indicative of greater symptom burden.

Table 3.

Summary of effect sizes

| Analysis | Hedges’ g | p | CI LL | CI UL | k | Q | Q p-value | I^2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All outcomes | ||||||||

| Post | .44 | .06 | −0.02 | 0.90 | 17 | 112.48 | .00 | 89 |

| Post (outlier) | .23 | .02 | 0.02 | 0.44 | 16 | 26.50 | .03 | 40 |

| Short-term follow-up | .09 | .35 | −0.10 | 0.29 | 5 | 7.07 | .13 | 0 |

| Long-term follow-up | .18 | .21 | −0.10 | 0.47 | 2 | 0.18 | .67 | 0 |

| Active control only | −.07 | .84 | −0.79 | 0.65 | 6 | 16.53 | .01 | 73 |

| Usual care only | .26 | .00 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 10 | 7.71 | .56 | 1 |

| MBI only | .17 | .05 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 9 | 10.41 | .23 | 0 |

| Med. movement only | .28 | .29 | −0.24 | 0.80 | 7 | 17.47 | .00 | 74 |

| Yoga only | .30 | .21 | −0.16 | 0.76 | 3 | 1.19 | .54 | 0 |

| TCQ only | .29 | .52 | −0.59 | 1.18 | 4 | 16.20 | .00 | 88 |

| HRQoL | ||||||||

| Post | .22 | .04 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 8 | 8.04 | .32 | 2 |

| Active control only | −.59 | .15 | −1.40 | 0.21 | 3 | 0.15 | .92 | 0 |

| Usual care only | .30 | .01 | 0.05 | 0.53 | 5 | 3.69 | .44 | 10 |

| MBI only | .23 | .17 | −0.10 | 0.56 | 4 | 3.37 | .34 | 14 |

| Med. movement only | .15 | .56 | −0.35 | 0.66 | 4 | 4.63 | .20 | 39 |

| NMH | ||||||||

| Post | .20 | .09 | −0.03 | 0.43 | 14 | 23.82 | .03 | 44 |

| Active control only | .02 | .96 | −0.72 | 0.76 | 5 | 15.67 | .00 | 77 |

| Usual care only | .20 | .02 | 0.02 | 0.38 | 9 | 7.18 | .51 | 0 |

| MBI only | .16 | .16 | −0.05 | 0.31 | 9 | 8.99 | .34 | 0 |

| Med. movement only | .30 | .37 | −0.35 | 0.95 | 5 | 14.45 | .00 | 78 |

| PMH | ||||||||

| Post | .21 | .33 | −0.22 | 0.65 | 5 | 8.94 | .06 | 51 |

| Usual care only | .29 | .01 | 0.05 | 0.53 | 4 | 3.70 | .44 | 10 |

| Short-term follow-up | .30 | .05 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 2 | 0.56 | .45 | 0 |

| Long-term follow-up | .18 | .21 | −0.10 | 0.47 | 2 | 0.18 | .67 | 0 |

Significant values in bold text. MBI and Med. Movement subgroups not reported for PMH outcomes as all five studies were MBI interventions. Active control only not reported as four of the five studies were usual care only.

HRQoL, health-related quality of life; LL, lower limit; MBI, mindfulness-based interventions; NMH, negative mental health; PMH, positive mental health; UL, upper limit.

For postintervention follow-up scores using the synthetic variables, the Q value (p < .0001) suggested substantial heterogeneity with I^2 of 89.98%. The overall effect size, based on a random-effects model, indicated a beneficial effect of MCIs on psychosocial outcomes in male cancer patients (Hedges’ g = .46, 95% CI: −0.03 to 0.95, p < .06). Follow-up analyses using both a visual inspection of the forest plot and statistical test for outliers indicated that one study (Chuang) had an outsized impact on the heterogeneity value and the overall effect size (Fig. 3) [47]. As studies with a DFBETA value greater than 1 are considered unusually influential (the value was 1.98 for the Chuang study), there was reasonable rationale for the removal of this study from the analysis. Removing this one study from the data set produced a modestly heterogeneous finding with a Q value of p = .03, with an I^2 of 40%. There was also a significant but more modest beneficial effect found for MCIs when excluding this one study (Hedges’ g = .23, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.44, p =.03). This study was removed from subsequent results in this results section

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of all outcomes with outlier removed (effect size above 0 favors intervention).

For short-term follow-up scores (e.g., those conducted within 3 months of intervention completion), 15 measures from five studies were available for analysis [46, 48, 50, 54, 60]. Heterogeneity was very low (p-value of Q = .25, I^2 of 0%) and the effect size was much m46ore modest, and nonsignificant than the postintervention effect found for all studies (Hedges’ g = .09, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.29, p = .35). For comparison, these same five studies, which measured a short-term follow-up, had similar postintervention results (Hedges’ g = .12, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.32). Only two of the 17 studies reported long-term follow-up scores (i.e., longer than 3 months postintervention) [46, 58]. For these two studies, the effect was nearly identical to the five studies evaluated for short-term follow-ups. There was low heterogeneity but a nonsignificant small effect size (Hedges’ g = .08, 95% CI −0.15 to 0.31, p = .50).

Active Versus Usual Care Control

An analysis of studies with usual care groups (n = 10) was nonsignificantly heterogeneous (Q = 7.7, p = .56, I^2 = 1%) and had strong evidence in favor of a small effect (Hedges’ g = .26, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.42, p = .001) [44, 46, 48, 49, 51, 53, 54, 56, 58, 59]. This was in stark contrast to an analysis of studies with active control groups (n = 6), which had substantial heterogeneity (Q = 18.3, p = .002, I2 = 76%) and did not have strong evidence for an effect in favor of the control group (Hedges’ g = −.07, 95% CI −0.79 to 0.64, p = .84) [45, 50, 52, 55, 57, 60]. Removing the one study that found an intervention effect, and which included significantly more intervention time and intensity (Campo), produced a highly nonheterogeneous result (Q = 2.32, p = .6, I^2 = 5%) of a null effect (Hedges’ g = −.31, 95% CI −0.68 to 0.07, p = .11).

Meditative Movement Versus MBIs

Another subgroup analysis that was carried out was based on whether the intervention was an MBI intervention (n = 9) or whether the study was a meditative movement intervention (n = 7; i.e., pooled studies of TCQ or Yoga). The MBIs were nonsignificant for heterogeneity of Q (p = .23 and I^2 of 0%) [46, 49–52, 54, 56, 58, 59]. The effect size, which was statistically significant, approached the threshold for a small effect (Hedges’ g = .17, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.35, p = .05). For the meditative movement interventions, there was a high degree of heterogeneity Q with p = .007 and I^2 of 74% [44, 45, 48, 53, 55, 57, 60]. The nonsignificant effect size was slightly larger for meditative movement than for the MBIs (Hedges’ g = .28, 95% CI −0.24 to 0.80, p = .29). The large heterogeneity for this pooled analysis prompted a follow-up analysis of the TCQ and Yoga separately. Neither category suggested strong evidence of an effect at the level of a summary psychosocial variable (Yoga was not heterogeneous, Q (p = .54) and I^2 of 0%, Hedges’ g = .29, 95% CI −0.17 to 0.76, p = .21, TCQ was highly heterogeneous, Q (p = .001) and I2 of 88%, Hedges’ g = .29, 95% CI −0.5 to 1.1, p = .5).

Negative Mental Health (e.g., Depression, Anxiety, and Distress)

Fourteen studies had at least one measure of NMH (e.g., depression, anxiety, psychological distress) [45, 46, 48–54, 56–60]. There was moderate heterogeneity across these measures (Q = 23.8, p = .03; I^2 = 44%) and nonsignificant trend toward a small beneficial effect on NMH among the MCIs (Hedges’ g = .20, 95% CI −0.03 to 0.43, p = .09). As with the results from considering all psychosocial measures together, when subanalyzed by control condition (n = 9), usual care again showed a small effect (Hedges’ g = .20, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.3, p = .02; Q = 7.17, p = .5; I^2 = 0%) [46, 48, 49, 51, 53, 54, 56, 58, 59]. The studies with active controls (n = 5) did not demonstrate strong evidence for any beneficial effect on NMH (Hedges’ g = .02, 95% CI −0.72 to 0.76, p = .02; Q = 15.6, p = .003; I^2 = 77%).

Health-Related Quality of Life

Eight studies measured HRQoL [44, 46, 49, 52–55, 57]. There was strong evidence for a small beneficial effect of MCIs on HRQoL at postintervention (Hedges’ g = .22, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.44, p = .04; Q = 8.1, p = .32; I^2 = 2%). A difference was found when comparing the studies utilizing active controls versus those with usual care. The usual care group had strong evidence for a small beneficial effect of MCIs on HRQOL immediately postintervention (Hedges’ g = .30, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.53, p = .01; Q = 3.6, p =. 44; I^2 = 10%). Meanwhile, the active control groups had a trend toward a medium negative effect on HRQOL for MCIs at postintervention (Hedges’ g = −.59, 95% CI −1.40 to 0.21, p = .15; Q = 3.6, p = .44; I^2 = 10%).

Positive Mental Health

Five studies measured PMH constructs (e.g., posttraumatic growth, self-compassion, and spirituality) at the postintervention time point [46, 52, 54, 58, 59]. An analysis of these five studies yielded a small beneficial effect in favor of MCIs, that was nonheterogeneous but not statistically significant (Hedges’ g = .21, 95% CI −0.22 to 0.65, p = .33; Q = 8.9, p = .06; I^2 = 51%). All of these studies were MBIs, so no comparison was possible with meditative movement interventions. Only one of the studies used an active control group (Nakamura), while four of the studies were usual care comparison groups. Analyzing the four studies that were usual care conditions together also demonstrated a small beneficial effect in favor of the MBIs that was nonheterogeneous (Hedges’ g = .29, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.53, p = .01; Q = 3.7, p = .44; I^2 = 10%). Two studies measured PMH at short-term and long-term follow-up. There was a statistically significant small beneficial effect at short-term follow-up (Hedges’ g = .30, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.60, p =.05; Q = .56, p = .45; I^2 = 0%) and a nonsignificant small effect at long-term follow-up (Hedges’ g = .18, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.47, p = .21; Q = .18, p = .67, I^2 = 0%).

Discussion

This meta-analysis is among the first to report on the effect of MBIs and meditative movement interventions in male cancer patients. Several analyses demonstrated evidence of an effect in favor of MCIs immediately postintervention on psychosocial outcomes for men with cancer. With the removal of one outlier from the 17 eligible studies for this meta-analysis, the overall impact of MCIs on male cancer psychosocial outcomes immediately postintervention was small (g = .23). Because of the modest heterogeneity considering the total sample, subgroups were analyzed to test for intervention effects. Whether studies had a usual care group versus an active control condition differed in psychosocial outcomes as studies that had a usual care control group demonstrated a small effect in favor of MCIs (g = .26), while studies with active control groups (except one study) failed to demonstrate a significant effect for or against the interventions. MBIs, as a category, demonstrated a small effect when considering all psychosocial outcomes together (g = .17). Considering outcomes by psychosocial domain yielded nearly identical effect sizes across each of the three categories with only HRQoL outcomes reaching significance (g = .22). At short-term follow-up assessments, there was a small effect on PMH outcomes (g = .30).

There are several important findings from this meta-analysis of male cancer patients who participated in MCI RCTs. Perhaps most notable are the small effect sizes found for psychosocial outcomes immediately postintervention. These effect sizes are appreciably more modest than the outcomes reported in much of the mindfulness-based and meditative movement literature for both the general population as well as the (predominantly female sex) cancer population [62]. Owing perhaps to the relatively modest statistical power with smaller subsamples of men in the present analysis, there were nonsignificant effects for a number of the major outcomes of interest. The effects found are quite close to those found in a recent meta-analysis of Tai Chi and Qigong for cancer-related symptoms that included a similar number of RCTs, although 75% of the study population was female and it had twice as many participants as the current meta-analysis [26].

Another important finding of the current study was the moderating effect of the type of control group used. Although usual care and wait-list conditions are more standard for establishing an effect of an intervention relative to no treatment, MBSR, Tai Chi/Qigong, and Yoga interventions are at the stage of needing to be tested against active controls in RCTs in cancer populations [63].

In addition to concerns about the quality of the control comparisons used, there was a lack of long-term, and even short-term, follow-up assessments beyond the immediate intervention period in otherwise very high-quality studies. One intriguing signal was the presence of a statistically significant small effect for PMH found at the short-term follow-up. Although there was limited power and results to demonstrate effects across other domains, this finding highlights the possibility that some effects may grow larger over time for certain interventions and, thus, immediate postintervention results may downplay their ultimate impact. For instance, breast cancer survivors randomized to an MBSR condition improved on posttraumatic growth scores slowly such that their long-term follow-up scores were greater than their postintervention results [64]. Long-term follow-up studies are also important for establishing to what degree the gains seen on psychosocial outcomes postintervention are durable, as well as what factors (e.g., continued home practice) might lead to longer lasting benefits.

There was a high degree of heterogeneity in the current sample as it included large definitive and longitudinal trials, as well as pilot studies. However, given the opportunity costs of administering high-quality clinical trials, there is a need to demonstrate durable effects for interventions. There is fairly robust evidence for MBI and meditative movement interventions to yield small-to-medium effect sizes on psychosocial outcomes at postintervention, but it is imperative that these gains be maintained over time to demonstrate the efficacy of effects. Given the time and cost of recruiting and running large-scale trials, longitudinal follow-ups (e.g., 3, 6, and/or 12 months) should be required for consideration of future trials in supportive oncology. In addition to measuring the long-term outcomes of participants in MCIs, studies should also take care to measure adherence, particularly postintervention. Optimizing dosage and design of interventions is necessary but not sufficient if adherence to continuing practice is necessary to maintain improvements to psychosocial health.

Contrary to expectations in the creation of the male data ratio, there was no significant effect size change between the data reported by authors for men and the data reported for all participants, men and women, in the published studies. While it is possible that men may do worse in the few studies that did not provide the data on male participants, it seems more likely that, on average, men experience small psychosocial gains following the completion of MCIs. However, there is not strong evidence for improvement on these outcomes when an active control group is used as the comparison. This finding differs from the published meta-analytic reviews for breast cancer. However, even the effect sizes found for MCIs in breast cancer survivors have become more modest over time, perhaps reflecting higher quality studies included in the analyses [24]. It could be that men, and studies that include a significant number of men, are different in important ways that impact study outcomes. These could be due to differences in expectancy effects. It could also be true as well that as higher-quality studies are conducted, the initial moderate-to-large effect sizes for psychosocial outcomes will become more modest across all kinds of MCIs.

Although there is unlikely sufficient power to detect a difference in this analysis between MBIs and meditative movement studies, there is a signal in the direction of men benefitting more on psychosocial outcomes from meditative movement interventions (e.g., Yoga and Tai Chi) as compared to interventions that do not include exercise (e.g., MBIs). Notably, the one study (Campo) that included an active control group, and still found a significant effect in favor of the MCI, had an intervention that included significantly higher exercise intensity and frequent classes (twice a week for 12 weeks) compared to other interventions tested. Whether meditative movement interventions have a superior effect for men with cancer is an empirical question that has yet to be demonstrated. However, meditative movement interventions may be viewed as more active and “athletic” compared to MBIs, which could increase the acceptability of these interventions among men. Although our meta-analysis has referred to biological sex as the description for men, the impact of gender expectations and roles is certainly an important factor to consider. There could be cohort effects as the male cancer survivors are, on the whole, over the age of 60. Although the present study suggests that men may still improve on these outcomes, perhaps less compared to studies of women, there is still a need to assess the impact of such interventions on racially and ethnically diverse populations and the mechanisms underlying intervention effects. There may well be additional challenges in recruiting such populations, and the interventions may have to be adapted to be culturally relevant.

There are also several important limitations to the current study. One limitation is the relatively high dropout rate in 12 of the 17 studies under consideration. Few studies used intent-to-treat analyses to account for study dropouts, and higher rates of dropout are a risk for survivor bias. Dropout, as well as lack of interest in study participation, is particularly problematic with male populations in health care settings in general as well as in mindfulness interventions. It may be that the men who could benefit the most are the least likely to enroll in such programs [9]. This is a particular concern with a male population that may be less likely to join mindfulness-based and meditative moment kinds of interventions [28]. Several studies included in the present analysis reported potential participant’s reasons for declining participation (Campo, Nakamura, Sohl, Victorson, and Zernike) with only one (Victorson) formally reporting on percent enrolled. Common reasons for study refusal of those reporting included lack of interest, study distance, and lack of time. As reporting of study uptake is usually limited to pilot and feasibility studies, this too should be considered a limitation for assessing potential study bias.

Another limitation is the use of a “male data only ratio” to assume the total sample findings applied to the men in the studies when gender-specific effects were not reported and could not be obtained from the authors. While we felt this approach was a reasonable one given the comparison to other studies reporting total sample and male sex information separately, this remains an assumption on our part. A related limitation is our use of a composite summary variable that summarized all psychosocial outcomes from a single study. Given the relative lack of studies focused on psychosocial outcomes for men in MCI interventions, we wanted to cast a wide net to summarize existing evidence. We used the I^2 test of heterogeneity as one test of the appropriateness of combining across three domains and found an acceptably low value (40%) for all psychosocial outcomes using a single value from each of the 16 included studies. In addition to reporting the combined psychosocial scores, we have also examined each psychosocial domain independently. However, this approach has not been widely used and should be considered as a limitation. As more high-quality RCTs using MCIs in diverse populations are conducted, it will be possible to summarize the efficacy of these interventions with greater precision with studies using the same outcomes within different psychosocial domains.

Another limitation is the significantly heterogeneous population of men included in terms of cancer type, stage, and treatment. Prostate cancer, which has high survival rates, is the most common type of cancer represented, although men with cancers that have poorer survival prognosis, including lung cancer, are also included. The lack of reported information on these cancer types limits the power to detect potential moderators to understand what works, when, and for whom along the cancer care continuum. It could be that there are particularly important times for certain men to join in MCIs. While the men included in the present analysis are quite diverse in terms of cancer treatment, they are overrepresented by college-educated, white non-Hispanic men. Given this lack of diverse representation, it may also be important to consider how to adapt existing MCIs, including increasing awareness of and access to these interventions, as well as to develop new interventions that better target the downstream effects of cancer in men. These interventions should be developed with particular attention to feasibility and acceptability with respect to enrolling and retaining men from diverse backgrounds.

Psychosocial outcomes were chosen as the outcomes of consideration for this study as they are the most commonly measured across the MCIs we studied. They are also plausibly the most sensitive to change based on the traditional “symptom” targets of MBIs (e.g., MBSR). More than half of the studies had psychosocial outcomes as their reported primary outcome. As noted above, even when they are the primary outcome of interest of the study, participants are not always recruited or stratified on symptom levels. This could be an example of range restriction and having little room for improvement on outcomes such as anxiety and depression if the majority of participants are neither anxious nor depressed at baseline. A related limitation is that few studies included measures of personality traits (e.g., openness to experience and conscientiousness), which contribute to enrollment bias and may have accounted for some of the benefits seen postintervention.

In sum, this meta-analysis suggests that men participating in MCIs appear to gain some benefit, albeit small, on psychosocial outcomes compared to control conditions. However, there is only limited evidence that these benefits are found when there is an active control group or that these psychosocial improvements are durable when assessed at future time points. Future research is needed to help confirm these findings and also to clarify the boundary conditions of these effects. Greater number of participants, and larger numbers of studies, will help to more precisely identify men who might benefit most from these treatments of interest. In addition to finding out what works, including mechanisms underlying intervention effects, there may be particularly sensitive times or interventions, which may not demonstrate a benefit for men. Continuing to summarize and expand this evidence base will help oncologists and health care providers make appropriate referrals for men diagnosed with cancer, undergoing cancer treatment, and those who have completed cancer treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research used the facilities or services of the University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center (UNMCCC) and the Behavioral Measurement and Population Sciences (BMPS) and Biostatistics Shared Resources.

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R01CA203930: PI: Kinney; “Biobehavioral Effects of Tai Chi Qigong for Prostate Cancer Survivors with Fatigue”); State of New Mexico; the University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30CA118100); and the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Center (UL1TR001449).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions C.G.F.: Led study design, collected and analyzed the data, and led manuscript development and writing; K.E.V.: Collaborated on study design, assisted with manuscript development and writing; B.W.S.: Assisted with manuscript development and editing; A.Y.K.: Collaborated on study design, manuscript development and writing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent For this type of study formal consent is not required.

References

*References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

- 1. Mukherjee S. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: Prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM. Cancer survivorship issues: Life after treatment and implications for an aging population. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2662–2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stanton AL. Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5132–5137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M. It’s not over when it’s over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors–a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40:163–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ettridge KA, Bowden JA, Chambers SK, et al. “Prostate cancer is far more hidden…”: Perceptions of stigma, social isolation and help-seeking among men with prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27:e12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oancea SC, Cheruvu VK. Psychological distress among adult cancer survivors: Importance of survivorship care plan. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:4523–4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao G, Okoro CA, Li J, White A, Dhingra S, Li C. Current depression among adult cancer survivors: Findings from the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38:757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burg MA, Adorno G, Lopez ED, et al. Current unmet needs of cancer survivors: Analysis of open-ended responses to the American Cancer Society Study of Cancer Survivors II. Cancer. 2015;121:623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥ 5 years) cancer survivors—A systematic review of quantitative studies. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl. Health Stat Report. 2015;79:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Creswell JD. Mindfulness interventions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2017;68:491–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ludwig DS, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA. 2008;300:1350–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiesa A, Malinowski P. Mindfulness-based approaches: Are they all the same? J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:404–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harrington A, Dunne JD. When mindfulness is therapy: Ethical qualms, historical perspectives. Am Psychol. 2015;70:621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larkey L, Jahnke R, Etnier J, Gonzalez J. Meditative movement as a category of exercise: Implications for research. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6:230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Payne P, Crane-Godreau MA. Meditative movement for depression and anxiety. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrison AM, Scott W, Johns LC, Morris EMJ, McCracken LM. Are we speaking the same language? Finding theoretical coherence and precision in “Mindfulness-Based Mechanisms” in chronic pain. Pain Med. 2017;18:2138–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carlson LE, Zelinski E, Toivonen K, et al. Mind-body therapies in cancer: What is the latest evidence? Curr Oncol Rep. 2017;19:67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haller H, Winkler MM, Klose P, Dobos G, Kümmel S, Cramer H. Mindfulness-based interventions for women with breast cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:1665–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Danhauer SC, Addington EL, Sohl SJ, Chaoul A, Cohen L. Review of yoga therapy during cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1357–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wayne PM, Lee MS, Novakowski J, et al. Tai Chi and Qigong for cancer-related symptoms and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12:256–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zeng Y, Luo T, Xie H, Huang M, Cheng AS. Health benefits of qigong or tai chi for cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zainal NZ, Booth S, Huppert FA. The efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction on mental health of breast cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1457–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Olano HA, Kachan D, Tannenbaum SL, Mehta A, Annane D, Lee DJ. Engagement in mindfulness practices by U.S. adults: Sociodemographic barriers. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21:100–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bodenlos JS, Strang K, Gray-Bauer R, Faherty A, Ashdown BK. Male representation in randomized clinical trials of mindfulness-based therapies. Mindfulness. 2017;8(2):259–265. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Forsythe LP, Kent EE, Weaver KE, et al. Receipt of psychosocial care among cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1961–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hyde MK, Newton RU, Galvao DA, et al. Men’s help-seeking in the first year after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2017;26(2):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chambers SK, Hyde MK, Oliffe JL, et al. Measuring masculinity in the context of chronic disease. Psychol Men Masc. 2016;17(3):228. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Carlson LE, Tamagawa R, Stephen J, et al. Tailoring mind-body therapies to individual needs: Patients’ program preference and psychological traits as moderators of the effects of mindfulness-based cancer recovery and supportive-expressive therapy in distressed breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. NHLBI/NIH. Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies 2018; Available at https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessibility verified July 1, 2018; 2018.

- 37. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR.. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Higgins JPT, Green S.. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1. 0. The Cochrane Collaboration; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011, pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Scammacca N, Roberts G, Stuebing KK. Meta-analysis with complex research designs: Dealing with dependence from multiple measures and multiple group comparisons. Rev Educ Res. 2014;84:328–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Keyes CL. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Revicki DA, Kleinman L, Cella D. A history of health-related quality of life outcomes in psychiatry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16:127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Viechtbauer W, Cheung MW. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1:112–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 44. *Ben-Josef AM, Chen J, Wileyto P, et al. Effect of Eischens yoga during radiation therapy on prostate cancer patient symptoms and quality of life: A randomized phase II trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;98:1036–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. *Campo RA, Agarwal N, LaStayo PC, et al. Levels of fatigue and distress in senior prostate cancer survivors enrolled in a 12-week randomized controlled trial of Qigong. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:60–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. *Chambers SK, Occhipinti S, Foley E, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in advanced prostate cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. *Chuang TY, Yeh ML, Chung YC. A nurse facilitated mind-body interactive exercise (Chan-Chuang qigong) improves the health status of non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients receiving chemotherapy: Randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;69:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. *Cohen L, Warneke C, Fouladi RT, Rodriguez MA, Chaoul-Reich A. Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in patients with lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100:2253–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. *Foley E, Baillie A, Huxter M, Price M, Sinclair E. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for individuals whose lives have been affected by cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. *Garland SN, Carlson LE, Stephens AJ, Antle MC, Samuels C, Campbell TS. Mindfulness-based stress reduction compared with cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia comorbid with cancer: A randomized, partially blinded, noninferiority trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. *Lehto RH, Wyatt G, Sikorskii A, Tesnjak I, Kaufman VH. Home-based mindfulness therapy for lung cancer symptom management: A randomized feasibility trial. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1208–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. *Nakamura Y, Lipschitz DL, Kuhn R, Kinney AY, Donaldson GW. Investigating efficacy of two brief mind-body intervention programs for managing sleep disturbance in cancer survivors: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:165–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. *Oh B, Butow P, Mullan B, et al. Impact of medical Qigong on quality of life, fatigue, mood and inflammation in cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:608–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. *Schellekens MPJ, van den Hurk DGM, Prins JB, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction added to care as usual for lung cancer patients and/or their partners: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2017;26:2118–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. *Sohl SJ, Danhauer SC, Birdee GS, et al. A brief yoga intervention implemented during chemotherapy: A randomized controlled pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2016;25:139–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. *Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. *Vanderbyl BL, Mayer MJ, Nash C, et al. A comparison of the effects of medical Qigong and standard exercise therapy on symptoms and quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1749–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. *Victorson D, Hankin V, Burns J, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary psychological benefits of mindfulness meditation training in a sample of men diagnosed with prostate cancer on active surveillance: Results from a randomized controlled pilot trial. Psychooncology. 2017;26:1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. *Zernicke KA, Campbell TS, Speca M, McCabe-Ruff K, Flowers S, Carlson LE. A randomized wait-list controlled trial of feasibility and efficacy of an online mindfulness-based cancer recovery program: The eTherapy for cancer applying mindfulness trial. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. *Zhang LL, Wang SZ, Chen HL, Yuan AZ. Tai Chi exercise for cancer-related fatigue in patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:504–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sedgwick P. Limits of agreement (Bland-Altman method). BMJ. 2013;346: f1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ledesma D, Kumano H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cancer: A meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2009;18:571–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dimidjian S, Segal ZV. Prospects for a clinical science of mindfulness-based intervention. Am Psychol. 2015;70:593–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Carlson LE, Tamagawa R, Stephen J, Drysdale E, Zhong L, Speca M. Randomized-controlled trial of mindfulness-based cancer recovery versus supportive expressive group therapy among distressed breast cancer survivors (MINDSET): long-term follow-up results. Psychooncology. 2016;25:750–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.