Abstract

Tick-borne pathogens (TBPs) are considered zoonotic re-emerging pathogens, with ticks playing important roles in their transmission and ecology. Previous studies in South Korea have examined TBPs residing in ticks; however, there is no phylogenetic information on TBPs in ticks parasitizing native Korean goat (NKG; Capra hircus coreanae). The present study assessed the prevalence, risk factors, and co-infectivity of TBPs in ticks parasitizing NKGs. In total, 107 hard ticks, including Haemaphysalis longicornis, Ixodes nipponensis, and Haemaphysalis flava, were obtained from NKGs in South Korea between 2016 and 2019. In 40 tested tick pools, genes for four TBPs, namely Coxiella-like endosymbiont (CLE, 5.0%), Candidatus Rickettsia longicornii (45.0%), Anaplasma bovis (2.5%), and Theileria luwenshuni (5.0%) were detected. Ehrlichia, Bartonella spp., and severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus were not detected. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report CLE and T. luwenshuni in H. flava ticks in South Korea. Considering the high prevalence of Candidatus R. longicornii in ticks parasitizing NKGs, there is a possibility of its transmission from ticks to animals and humans. NKG ticks might be maintenance hosts for TBPs, and we recommend evaluation of the potential public health threat posed by TBP-infected ticks.

Keywords: tick-borne pathogens, phylogeny, Rickettsia, Theileria, Anaplasma, Coxiella, tick

1. Introduction

Ticks are considered the main arthropod vectors for infectious disease agents, and they are related to important veterinary and medical health issues [1]. Numerous emergent tick-borne pathogens (TBPs) had been circulating in animals and ticks long before their detection as causes of clinical diseases [2]. Although TBPs are preserved in stable natural cycles that involve domestic and/or wild animals and ticks, humans might be considered accidental hosts [3].

The control of transmission of zoonotic pathogens with regard to vertebrate hosts and ticks, which are related in a continually changing environment, is usually difficult because of habitat distributions, zoonotic/domestic hosts, and transmission cycles in regions with coexistence of pastured domestic animals and wild animals [4]. The global hazard of TBPs is continuing to increase and is raising public health worries, with the constant identification of new pathogens over the past 20 years [5].

Understanding the ecology of local tick species and recognizing TBPs have high health significance. There is a rapidly increasing number of reservoir-adapted pathogens among various species of ticks, which are known or suspected vectors of zoonotic TBPs. Previous studies have investigated the presence of TBPs in South Korea by assessing ticks and cattle, using molecular methods [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The native Korean goat (NKG, Capra hircus coreanae) is an individual breed of goat primarily raised for natural health supplements and meat in South Korea, and it is known to be an essential natural reservoir host of several TBPs that influence human, wildlife, and domestic animal populations [14,15]. As NKGs are reared near domestic animals, they can transmit TBPs to these animals. However, the importance of TBPs in ticks from small ruminants, such as NKG, in South Korea is not yet known. Additionally, TBP infections in goats may be neglected because of their low economic position in the NKG production industry in South Korea. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to investigate TBPs in ticks from NKGs and assess the molecular characteristics of several TBPs.

In this study, TBP surveillance was conducted to detect tick species parasitizing goats, and to identify related tick-borne zoonotic pathogens possibly negatively influencing medical health and veterinary medicine in South Korea. The study assessed the prevalence, risk factors, and co-infectivity of TBPs, including rickettsiae (Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, and Rickettsia), Bartonella spp., Coxiella burnetii, piroplasms (Babesia and Theileria), and severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), among ticks from NKGs in South Korea.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of Ticks

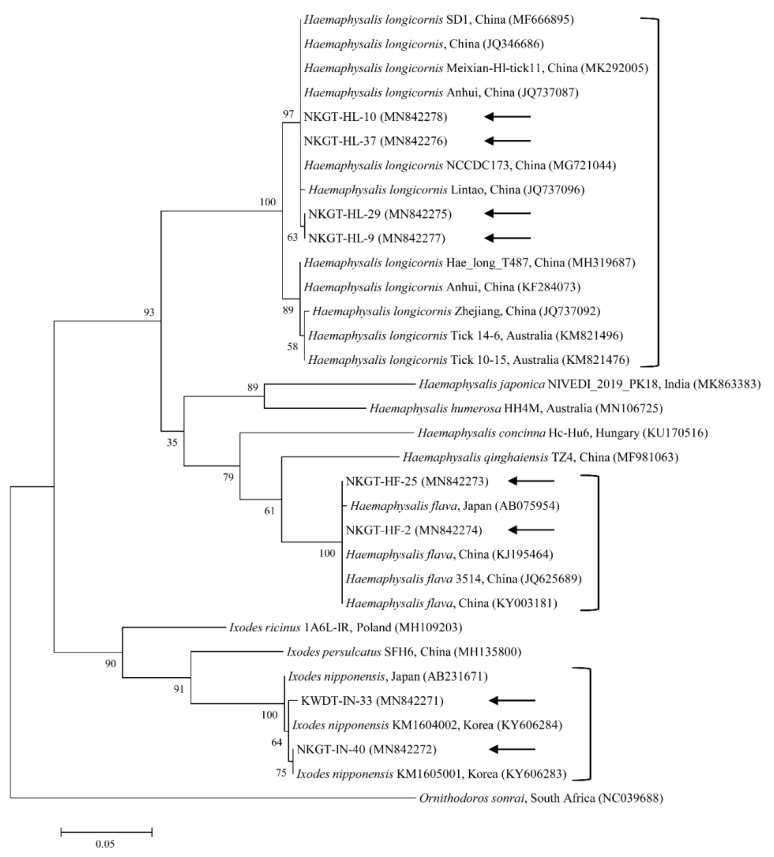

We obtained 107 ticks (40 tick pools) involving two genera and three species (Haemaphysalis longicornis, Ixodes nipponensis, and Haemaphysalis flava) from NKGs. In the tick samples, we used universal primers for the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (cox1) gene to amplify 710-bp fragments. The cox1 gene was obtained and sequenced from representative ticks to eliminate potential issues in identification, especially among nymphs and larvae. In this study, the cox1 gene sequences were divided into three groups according to nucleotide identity. The three groups shared close genetic relationships with H. longicornis (98.7–100% nucleotide identity), H. flava (98.8–100% nucleotide identity), and I. nipponensis (99.2–100% nucleotide identity). A phylogenetic tree was created according to the cox1 genes of several ticks deposited in GenBank, and the collected ticks were divided into three clades related to the following three species (Figure 1): H. longicornis (62.5%, 25/40 pools), H. flava (25.0%, 10/40 pools), and I. nipponensis (12.5%, 5/40 pools) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Molecular tick identification according to phylogenetic analysis using the maximum likelihood method with the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene. The analyzed sequences are indicated by arrows. The accession numbers for nucleotide sequences from GenBank are presented with species names and countries. The outgroup was Ornithodoros sonrai. The branch numbers mean bootstrap support (1000 replicates). The scale bar means phylogenetic distance.

Table 1.

Identified tick-borne pathogens in ticks from native Korean goats in South Korea, 2016–2019.

| Species | Stage | Tick Pool (n) |

A. bovis (16S) |

T. luwenshuni (18S) |

Coxiella-like Endosymbiont (16S) |

Candidatus R. Longicornii (16S) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (%) | 95% CI | Positive (%) | 95% CI | Positive (%) | 95% CI | Positive (%) | 95% CI | |||

| Haemaphysalis longicornis | Nymph | 15 | 1 (6.7) | 0–19.3 | 1 (6.7) | 0–19.3 | 1 (6.7) | 0–19.3 | 8 (53.3) | 28.1–78.6 |

| Adult | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (100) | 100 | |

| Haemaphysalis flava | Nymph | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adult | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0–67.4 | 1 (25.0) | 0–67.4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ixodes nipponensis | Nymph | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adult | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 40 | 1 (2.5) | 0–7.3 | 2 (5.0) | 0–11.8 | 2 (5.0) | 0–11.8 | 18 (45.0) | 29.6–60.4 | |

16S, 16S rRNA; 18S, 18S rRNA; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; A., Anaplasma; T., Theileria; R., Rickettsia.

2.2. Identification of TBPs

The 16S rRNA sequences of Anaplasma bovis (1/40 pools, 2.5%), Coxiella-like endosymbiont (CLE) (2/40 pools, 5.0%), and unidentified Rickettsia (18/40 pools, 45.0%) were detected in the ticks (Table 1). Additionally, the 18S rRNA sequence of Theileria luwenshuni (2/40 pools, 5.0%) was detected in the ticks (Table 1). Among the positive samples, additional genetic analysis revealed that the ticks were positive for unidentified Rickettsia citrate synthase (gltA) (18/40 pools, 45.0%).

With regard to infection, one (2.5%) tick was co-infected with T. luwenshuni, CLE, and unidentified Rickettsia, and one (2.5%) was co-infected with A. bovis and T. luwenshuni. Ehrlichia spp., Bartonella spp., and SFTSV were not detected in this study.

With regard to each pathogen, one (6.7%) H. longicornis nymph was positive for A. bovis; one (6.7%) H. longicornis nymph and one (25.0%) H. flava adult were positive for T. luwenshuni; one (6.7%) H. longicornis nymph and one (25.0%) H. flava adult were positive for CLE; and eight (53.3%) H. longicornis nymphs and 10 (100%) H. longicornis adults were positive for unidentified Rickettsia.

2.3. Molecular and Phylogenetic Analyses

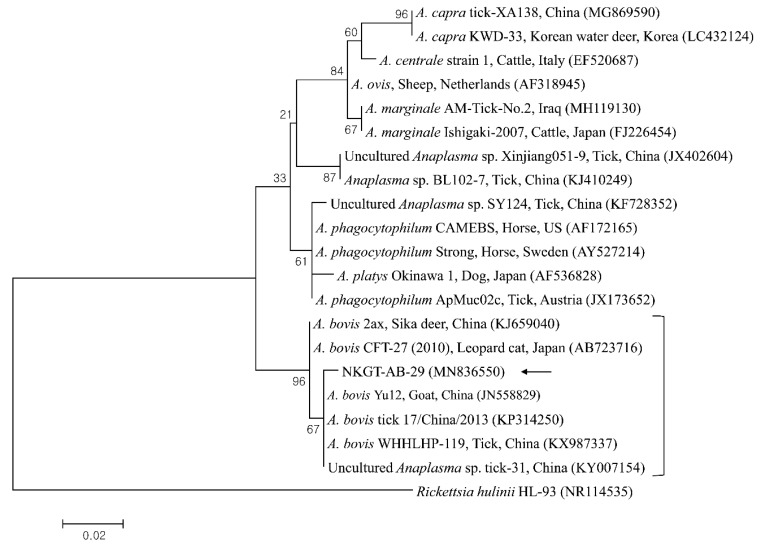

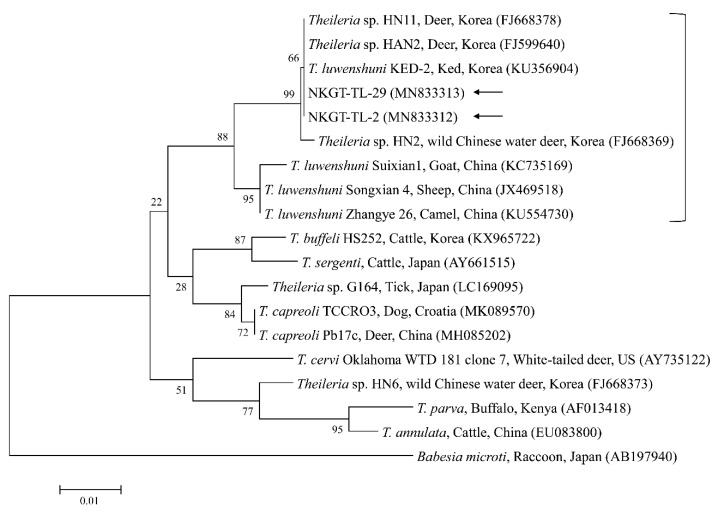

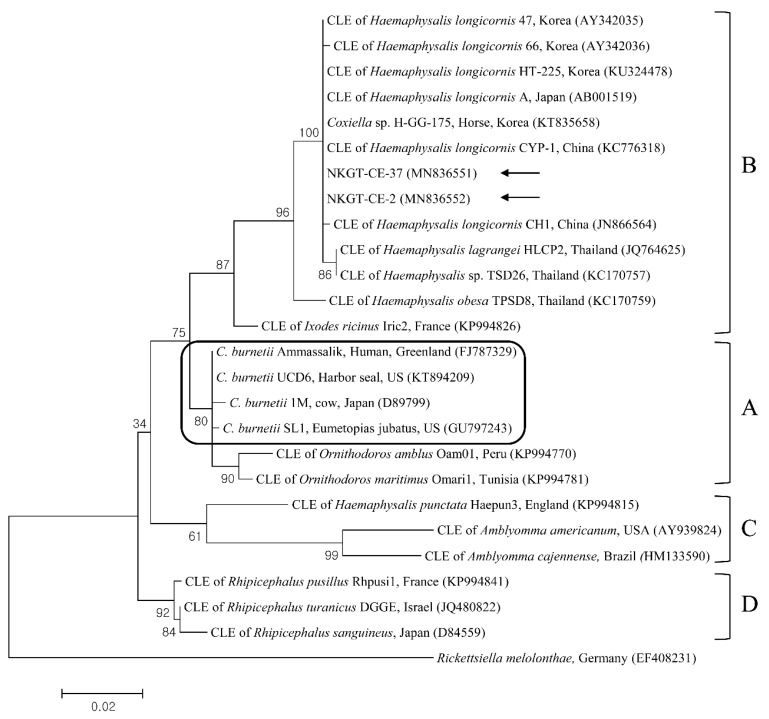

In phylogenetic analyses, the 16S rRNA sequences of A. bovis (Figure 2), 18S rRNA sequences of T. luwenshuni (Figure 3), 16S rRNA sequences of Coxiella (Figure 4), and 16S rRNA (Figure 5) and gltA (Figure 6) nucleotide sequences of Rickettsia were clustered with previously documented sequences.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree created with the maximum likelihood method and based on Anaplasma spp. 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences. The analyzed sequence is indicated by an arrow. The accession numbers for nucleotide sequences from GenBank are presented with species names and countries. The outgroup was Rickettsia hulinii. The branch numbers mean bootstrap support (1000 replicates). The scale bar means phylogenetic distance.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree created with the maximum likelihood method and based on Theileria spp. 18S rRNA nucleotide sequences. The analyzed sequences are indicated by arrows. The accession numbers for nucleotide sequences from GenBank are presented with species names and countries. The outgroup was Babesia microti. The branch numbers mean bootstrap support (1000 replicates). The scale bar means phylogenetic distance.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree created with the maximum likelihood method and based on Coxiella spp. 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences. The outgroup was Rickettsiella melolonthae. The analyzed sequences are indicated by arrows. Four clades of Coxiella are indicated as A to D. The Coxiella burnetii group is outlined within clade A. The accession numbers from GenBank for other sequences are presented with sequence names. The branch numbers mean bootstrap support (1000 replicates). The scale bar means phylogenetic distance. CLE = Coxiella-like endosymbionts.

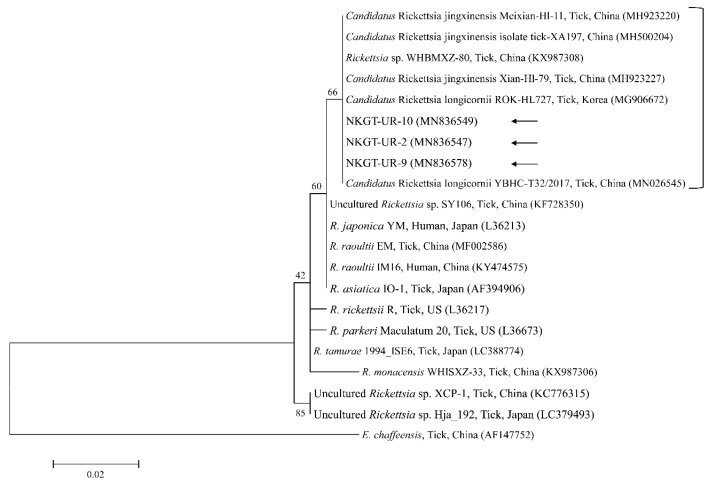

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree created with the maximum likelihood method and based on Rickettsia spp. 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences. The analyzed sequences are indicated by arrows. The accession numbers for nucleotide sequences from GenBank are presented with species names and countries. The outgroup was Ehrlichia chaffeensis. The branch numbers mean bootstrap support (1000 replicates). The scale bar means phylogenetic distance.

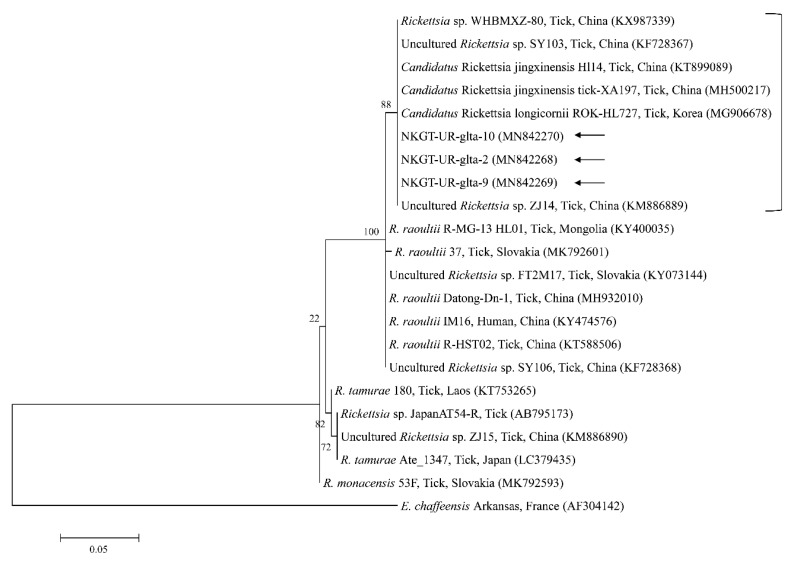

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree created with the maximum likelihood method and based on Rickettsia spp. gltA nucleotide sequences. The analyzed sequences are indicated by arrows. The accession numbers for nucleotide sequences from GenBank are presented with species names and countries. The outgroup was Ehrlichia chaffeensis. The branch numbers mean bootstrap support (1000 replicates). The scale bar means phylogenetic distance.

One sequence of A. bovis showed 98.8–99.5% identity with 16S rRNA sequences in previously reported A. bovis isolates. Two sequences of T. luwenshuni shared 100% identity with 18S rRNA sequences. They also shared 97–100% identity with 18S rRNA sequences in previously reported T. luwenshuni isolates. Two sequences of CLE shared 100% identity with 16S rRNA sequences. They also shared 98.4–100% identity with 16S rRNA sequences in previously reported CLE clade B isolates.

Three representative sequences of unidentified Rickettsia genes shared 100% identity with 16S rRNA and gltA sequences. They also shared 99.8–100% identity with 16S rRNA sequences and 97.6–99.2% identity with gltA sequences in previously reported unidentified Rickettsia isolates.

The identified representative sequences were submitted to GenBank. The accession numbers are as follows: MN842271–MN842272 (I. nipponensis), MN842273–MN842274 (H. flava), MN842275–MN842278 (H. longicornis), MN836550 (A. bovis), MN833312–MN833313 (T. luwenshuni), MN836551–MN836552 (CLE), MN836547–MN836549 (unidentified Rickettsia 16S rRNA), and MN842268–MN842270 (unidentified Rickettsia gltA).

3. Discussion

The present study found H. longicornis (62.5%), H. flava (25.0%), and I. nipponensis (12.5%) in NKGs, and the most common species was H. longicornis. These findings are similar to the results of a previous South Korean study, which found 569 H. longicornis organisms (38 nymphs, 369 male adults, and 162 female adults) from 27 goat farms [16].

The cox1 sequences from collected H. longicornis showed 97.1–99.6% nucleotide identity with known cox1 sequences of H. longicornis (Figure 1). The cox1 sequences from collected H. flava and I. nipponensis showed 98.3–98.7% and 98.2–99.8% nucleotide identity with known cox1 sequences, respectively (Figure 1). H. longicornis is mainly obtained from grasses and herbaceous vegetation, H. flava is frequently obtained from forests, and I. nipponensis is obtained from both habitats across South Korea [17]. All three ticks identified in this study are vectors and hosts for many TBPs and can transmit them to animals and humans in South Korea [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Several TBPs, including A. bovis, T. luwenshuni, CLE, and unidentified Rickettsia, were detected in NKG ticks via molecular analysis. The influences of diseases associated with Anaplasma regarding the health and productivity of animals have been known for over a century, and there is a major threat to industries related to livestock [18]. In nature, Anaplasma movement involves tick vectors, and there are many vertebrate hosts and infection sources for ticks, animals, and humans [18]. A. bovis, which is a monocytotropic species, has been identified among ruminants in numerous countries [19]. A. bovis is not considered a zoonotic pathogen, and it could be identified in cattle having subclinical signs, including lymphadenopathy, depression, fever, and abnormal conditions [20]. A. bovis was previously detected in South Korea in ticks (7.5%, 20/266 pools) from Korean water deer [7], in cattle (1.0%, 12/1219) [10], and in H. longicornis ticks (1.0%, 5/506 pools) [6]. Additionally, it has been detected in H. longicornis ticks (26.4%, 77/292) from goats in North Korea [8]. Moreover, Anaplasma spp. have been detected in NKGs (29.2%, 7/39) [15]. In the present study, one H. longicornis nymph from an NKG was positive for A. bovis.

Theileriosis, which is a tick-borne hemoprotozoan disease, can affect domestic animals, most frequently sheep and cattle in tropical and sub-tropical areas, and it causes high economic loss [21]. T. luwenshuni mainly infects small ruminants and is transmitted by H. longicornis [22]. In South Korea, T. luwenshuni has been previously identified in roe deer (100%, 23/23), and H. longicornis (34.8%, 8/23 pools) [11], and in deer keds from Korean water deer (75%, 6/8) [23]. In this study, two ticks (5.0%) from NKGs tested positive for T. luwenshuni (one H. longicornis nymph and one H. flava adult). To our knowledge, the present study is the first to report the presence of T. luwenshuni in H. flava ticks in Korea.

Q fever, which is caused by C. burnetii and is a zoonosis, has a global distribution, and it can result in a severe condition in animals and humans [24]. The biological features of CLE differ from those of C. burnetii, and some of the organisms might behave like symbionts that are engaged in complex interactions with ticks. It is considered that CLE are closely related to, but genetically distinct from, C. burnetii, suggesting extensive diversity within Coxiella. Through multilocus sequencing, Coxiella has been divided into at least four extremely divergent genetic clades (A to D), and C. burnetii has been categorized within clade A [25]. In South Korea, C. burnetii was previously identified in NKGs (9.5%, 57/597) [14], and CLE clade B was identified in H. longicornis ticks (52.4%, 121/213) from horses [9]. In this study, two ticks (5.0%) from NKGs tested positive for CLE clade B (one H. longicornis nymph and one H. flava adult). To our knowledge, the present study is the first to report the presence of CLE in H. flava ticks in Korea. However, in this study, C. burnetii was not detected. Additional investigations are needed to evaluate the prevalence of infection involving C. burnetii or CLE among ticks and NKGs.

Organisms from the genus Rickettsia have been divided into various groups, including the typhus group, spotted fever group (SFG), Rickettsia canadensis group, and Rickettsia bellii group [26]. Obligate intracellular bacteria belonging to the SFG cause tick-borne rickettsioses [27]. The significance and scope of recognized tick-borne rickettsial pathogens have greatly increased in the last 25 years, and thus, this disease complex is considered an ideal model for recognizing emerging and re-emerging infections [5]. In this study, one SFG rickettsia with Candidatus status was detected. A possibly novel SFG rickettsia classified into the putative new subgroup “Candidatus Rickettsia longicornii” was identified in the species H. longicornis (100%, 11/11 pools; 43.2%, 79/183) in South Korea [13]. These strains were clustered in a subcategory that represented a sister taxon separate from the known subcategories of SFG rickettsiae. Sequences of gene fragments in GenBank for rickettsial isolates obtained from H. longicornis in Japan, China, and South Korea have unknown pathogenicity and uncertain taxonomic statuses that are likely associated with Candidatus R. longicornii or a closely connected species [13]. The others were given provisory species names, including Candidatus Rickettsia jingxinensis from H. longicornis (1.0%, 2/204 pools) in China [28]. The two uncultured Rickettsia species were found to be the same species by phylogenetic analysis involving several genes [29]. In a previous study, unidentified new Rickettsia spp. in H. longicornis were Candidatus R. longicornii (16.7%, 52/311 pools) in South Korea [12] and Candidatus R. jingxinensis (32.0%, 303/947) in China [29]. Moreover, the XY118 (KU853023) isolate was obtained from a human, indicating its possible pathogenicity in humans. Additional studies are required to determine its pathogenicity. In the present study, unidentified Rickettsia spp. (45.0%) were detected in eight H. longicornis nymphs and 10 H. longicornis adults, and the pathogen was identified as Candidatus R. longicornii by phylogenetic analysis. Further surveys are needed to identify other novel Rickettsia spp. in ticks and their host animals.

The bootstrap support values need to be analyzed carefully. As a limitation in this study, some bootstrap values were low. This could be due to using small amplification fragments for phylogeny. Thus, an additional study is needed to analyze longer fragments of genes in phylogeny for better presentation of data.

In conclusion, four TBPs were identified in ticks obtained from NKGs in South Korea, including zoonotic pathogens of CLE and Candidatus R. longicornii. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of CLE and T. luwenshuni in H. flava ticks from South Korea. Additionally, there is a high prevalence of Candidatus R. longicornii in ticks parasitizing NKGs. Both local inhabitants of NKG farms and animals are at high risk of exposure to coxiellosis, anaplasmosis, theileriosis, and rickettsiosis. The present findings extend our knowledge of the distribution and probable vector spectrum of TBPs and suggest that ticks are a potential reservoir for TBP transmission to other animals and humans via bites. Investigation of the tick infestation risk is important, especially from the zoonotic and public health perspectives. These data associated with a high TBP prevalence in ticks indicate the requirement for further studies on the impacts of tick-borne diseases in animals and humans. Better understanding of local major tick species and thorough TBP characterization are essential to public health. Limited information is available about the TBPs of ticks from small ruminants, such as NKG, in South Korea. Although limited numbers of ticks were collected from goats in this study, tick abundance and distribution patterns were similar to those in previous studies [7,17], showing predominance of H. longicornis, followed by H. flava and I. nipponensis. Thus, we believe that the present findings extend our knowledge of the distribution and probable vector spectrum of TBPs.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Tick Collection and Species Identification

In 2018, the total number of NKGs reared in South Korea was reported to be 542,744 from 14,644 farms [30]. NKGs are mostly reared on small-scale farms and are allowed to graze freely in the pasture and mountain areas. These farms are in distant places. These factors were considered to hinder tick sampling. A total of 107 ticks were collected from NKGs in South Korea using a simple random sampling method by veterinarians at local veterinary institutions during treatment, surveillance, and monitoring or during regular check-up after receiving oral approval from NKG farm owners between 2016 and 2019. Two to ten ticks per NKG were collected from 19 NKGs, and they were preserved in 70% ethanol. The collected ticks were initially identified according to their morphological characteristics [31], with further classification according to the molecular methods described below. Subsequently, the ticks were pooled by species and developmental stage (nymph/adult) into 40 tick pools, with one to three ticks per pool.

4.2. Molecular Detection of Ticks and TBPs

A commercial DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Melbourne, Australia) was used according to the provided instructions for genomic DNA extraction from the ticks. The extracted DNA was kept at −20 °C. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was conducted using the AccuPower® ProFi Taq PCR Premix Kit (Bioneer, Daejeon, South Korea). Molecular identification of tick species was conducted by amplifying the sequence of the cox1 gene using specific primers [32].

The ticks were then screened for several TBPs with primers specific to each pathogen. The presence of rickettsiae was initially assessed by PCR with a commercial AccuPower® Rickettsiales 3-Plex PCR Kit (Bioneer) for the detection of rickettsiae 16S rRNA. For species identification, positive samples were then amplified further. For Rickettsia spp., positive samples were confirmed by PCR that targeted gltA [33]. Multiple primers were used to amplify the 16S rRNA fragment for the genus Coxiella (including C. burnetii and CLE) [9]. Additionally, nested PCR (nPCR) was used to amplify the internal transcribed spacer region sequence of Bartonella spp. [34]. The S segment of SFTSV was amplified by nPCR [35]. Piroplasm infection was initially screened using a commercial AccuPower® Babesia & Theileria PCR Kit (Bioneer) to detect piroplasm 18S rRNA. Positive samples were then re-amplified by PCR using primers designed from the common sequence of the 18S rRNA gene of some piroplasm species [36].

All primers and amplification conditions used for the detection of TBPs in ticks from NKGs in the present study are described in Supplementary Table S1.

4.3. DNA Cloning

Agarose gel extraction kits (Qiagen) were used to purify positive PCR products. The purified products were introduced into pGEM-T Easy vectors (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the provided instructions. The ligated products were then transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α-competent cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA), and the cells were incubated at 37 °C overnight. Plasmid DNA was extracted using the Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Qiagen), according to the provided instructions.

4.4. Nucleotide Sequencing and Phylogeny

Sequencing was performed using recombinant plasmid clones. The sequences were analyzed and aligned with the multiple sequence alignment CLUSTAL Omega (v. 1.2.2) program, and the alignments were corrected with BioEdit (v. 7.0.4). Phylogeny was assessed with the maximum likelihood method and the Kimura 2-parameter distance model in MEGA (v. 5.0). Sequence analysis involved a similarity matrix. For tree stability, bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates was performed.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of South Korea (NRF).

Supplementary Material

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Primers used for the detection of tick-borne pathogens in ticks from native Korean goats (Capra hircus coreanae) in the present study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-G.S. and D.K.; official analysis, O.-D.K. and D.K.; funding acquisition, D.K.; methodology, M.-G.S.; supervision, D.K.; validation, O.-D.K. and D.K.; writing—original draft, M.-G.S.; writing—editing and review, O.-D.K. and D.K. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education (Grant No. NRF-2016R1D1A1B02015366).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Colwell D.D., Dantas-Torres F., Otranto D. Vector-borne parasitic zoonoses: Emerging scenarios and new perspectives. Vet. Parasitol. 2011;182:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baneth G. Tick-borne infections of animals and humans: A common ground. Int. J. Parasitol. 2014;44:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De la Fuente J., Estrada-Pena A., Venzal J.M., Kocan K.M., Sonenshine D.E. Overview: Ticks as vectors of pathogens that cause disease in humans and animals. Front. Biosci. A J. Virtual Libr. 2008;13:6938–6946. doi: 10.2741/3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salkeld D.J., Lane R.S. Community ecology and disease risk: Lizards, squirrels, and the Lyme disease spirochete in California, USA. Ecology. 2010;91:293–298. doi: 10.1890/08-2106.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parola P., Paddock C.D., Socolovschi C., Labruna M.B., Mediannikov O., Kernif T., Abdad M.Y., Stenos J., Bitam I., Fournier P.E., et al. Update on tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: A geographic approach. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013;26:657–702. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00032-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh J.Y., Moon B.C., Bae B.K., Shin E.H., Ko Y.H., Kim Y.J., Park Y.H., Chae J.S. Genetic identification and phylogenetic analysis of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species in Haemaphysalis longicornis collected from Jeju island, Korea. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 2009;39:257–267. doi: 10.4167/jbv.2009.39.4.257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang J.G., Ko S., Kim H.C., Chong S.T., Klein T.A., Chae J.B., Jo Y.S., Choi K.S., Yu D.H., Park B.K., et al. Prevalence of Anaplasma and Bartonella spp. in ticks collected from Korean water deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus) Korean J. Parasitol. 2016;54:87–91. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2016.54.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang J.G., Ko S., Smith W.B., Kim H.C., Lee I.Y., Chae J.S. Prevalence of Anaplasma; Bartonella and Borrelia Species in Haemaphysalis longicornis collected from goats in North Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2016;17:207–216. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2016.17.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seo M.G., Lee S.H., VanBik D., Ouh I.O., Yun S.H., Choi E., Park Y.S., Lee S.E., Kim J.W., Cho G.J., et al. Detection and genotyping of Coxiella burnetii and Coxiella-like bacteria in horses in South Korea. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0156710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo M.G., Ouh I.O., Lee H., Geraldino P.J.L., Rhee M.H., Kwon O.D., Kwak D. Differential identification of Anaplasma in cattle and potential of cattle to serve as reservoirs of Anaplasma capra, an emerging tick-borne zoonotic pathogen. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;226:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moon K.H., Lee S., Choi C.Y., Kim S.Y., Kang C.W., Lee K.K., Yun Y.M. Investigation of Theileria sp. from ticks and roe deer (Capreolus pygargus) in jeju island. J. Vet. Clin. 2014;31:6–10. doi: 10.17555/ksvc.2014.02.31.1.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noh Y., Lee Y.S., Kim H.C., Chong S.T., Klein T.A., Jiang J., Richards A.L., Lee H.K., Kim S.Y. Molecular detection of Rickettsia species in ticks collected from the southwestern provinces of the Republic of Korea. Parasites Vectors. 2017;10:20. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1955-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang J., An H., Lee J.S., O’Guinn M.L., Kim H.C., Chong S.T., Zhang Y., Song D., Burrus R.G., Bao Y., et al. Molecular characterization of Haemaphysalis longicornis-borne rickettsiae, Republic of Korea and China. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9:1606–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung B.Y., Seo M.G., Lee S.H., Byun J.W., Oem J.K., Kwak D. Molecular and serologic detection of Coxiella burnetii in native Korean goats (Capra hircus coreanae) Vet. Microbiol. 2014;173:152–155. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seong G., Han Y.J., Chae J.B., Chae J.S., Yu D.H., Lee Y.S., Park J., Park B.K., Yoo J.G., Choi K.S. Detection of Anaplasma sp. in Korean native goats (Capra aegagrus hircus) on Jeju Island, Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2015;53:765–769. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2015.53.6.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chae J.B., Cho Y.S., Cho Y.K., Kang J.G., Shin N.S., Chae J.S. Epidemiological investigation of tick species from near domestic animal farms and cattle; goat; and wild boar in Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2019;57:319–324. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2019.57.3.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chong S.T., Kim H.C., Lee I.Y., Kollars T.M., Jr., Sancho A.R., Sames W.J., Chae J.S., Klein T.A. Seasonal distribution of ticks in four habitats near the demilitarized zone, Gyeonggi-do (Province), Republic of Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2013;51:319–325. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2013.51.3.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Battilani M., De Arcangeli S., Balboni A., Dondi F. Genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology of Anaplasma. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017;49:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z., Ma M., Wang Z., Wang J., Peng Y., Li Y., Guan G., Luo J., Yin H. Molecular survey and genetic identification of Anaplasma species in goats from central and southern China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:464–470. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06848-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ooshiro M., Zakimi S., Matsukawa Y., Katagiri Y., Inokuma H. Detection of Anaplasma bovis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum from cattle on Yonaguni Island, Okinawa, Japan. Vet. Parasitol. 2008;154:360–364. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uilenberg G. International collaborative research: Significance of tick-borne hemoparasitic diseases to world animal health. Vet. Parasitol. 1995;57:19–41. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)03107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y., Zhang X., Liu Z., Chen Z., Yang J., He H., Guan G., Liu A., Ren Q., Niu Q., et al. An epidemiological survey of Theileria infections in small ruminants in central China. Vet. Parasitol. 2014;200:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S.H., Kim K.T., Kwon O.D., Ock Y., Kim T., Choi D., Kwak D. Novel detection of Coxiella spp., Theileria luwenshuni, and T. ovis endosymbionts in deer keds (Lipoptena fortisetosa) PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0156727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madariaga M.G., Rezai K., Trenholme G.M., Weinstein R.A. Q fever: A biological weapon in your backyard. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003;3:709–721. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duron O., Noël V., McCoy K.D., Bonazzi M., Sidi-Boumedine K., Morel O., Vavre F., Zenner L., Jourdain E., Durand P., et al. The recent evolution of a maternally-inherited endosymbiont of ticks led to the emergence of the Q fever pathogen; Coxiella burnetii. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004892. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merhej V., Angelakis E., Socolovschi C., Raoult D. Genotyping, evolution and epidemiological findings of Rickettsia species. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;25:122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parola P., Paddock C.D., Raoult D. Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: Emerging diseases challenging old concepts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:719–756. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.719-756.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H., Li Q., Zhang X., Li Z., Wang Z., Song M., Wei F., Wang S., Liu Q. Characterization of rickettsiae in ticks in northeastern China. Parasites Vectors. 2016;9:498. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1764-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo W.P., Wang Y.H., Lu Q., Xu G., Luo Y., Ni X., Zhou E.M. Molecular detection of spotted fever group rickettsiae in hard ticks, northern China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019;66:1587–1596. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, South Korea (MAFRA) Major Statistics of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs during 2019. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs; Sejong, Korea: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barker S.C., Walker A.R. Ticks of Australia. The species that infest domestic animals and humans. Zootaxa. 2014;3816:1–144. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3816.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folmer O., Black M., Hoeh W., Lutz R., Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reis C., Cote M., Paul R.E., Bonnet S. Questing ticks in suburban forest are infected by at least six tick-borne pathogens. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:907–916. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko S., Kim S.J., Kang J.G., Won S., Lee H., Shin N.S., Choi K.S., Youn H.Y., Chae J.S. Molecular detection of Bartonella grahamii and B. schoenbuchensis-related species in Korean water deer (Hydropotes inermis argyropus) Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:415–418. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2012.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshikawa T., Fukushi S., Tani H., Fukuma A., Taniguchi S., Toda S., Shimazu Y., Yano K., Morimitsu T., Ando K., et al. Sensitive and specific PCR systems for detection of both Chinese and Japanese severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus strains and prediction of patient survival based on viral load. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:3325–3333. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00742-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casati S., Sager H., Gern L., Piffaretti J.C. Presence of potentially pathogenic Babesia sp. for human in Ixodes ricinus in Switzerland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2006;13:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.