Abstract

Acinetobacter junii is one of more than 50 different species belonging to the genus Acinetobacter. This bacterium is rarely reported to cause human infections. Here we described a rare case of Acinetobacter junii, which grew in urine culture approximately one month after the patient was discharged from the hospital with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection, which caused left obstructing renal calculi requiring nephrostomy tube placement.

Keywords: Urinary tract infection, Acinetobacter junii, VITEK

Highlights

-

•

Acinetobacter is often considered to be ubiquitous in nature.

-

•

Acinetobacter junii is rarely reported to cause human infections.

-

•

A rare case of Acinetobacter junii, which grew in urine culture, was described.

Introduction

Acinetobacter is a gram-negative coccobacillus, which naturally inhabits water and soil as well as pets, arthropods, and food animals.1 In humans, it can colonize skin, wounds, respiratory or gastrointestinal tracts as well as oral mucosa, predisposing to pneumonia in the event of aspiration into the lower respiratory tract.2 Certain Acinetobacter species account for some healthcare-associated infections such as ventilator associated pneumonia, central line-associated bloodstream infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, and surgical site infections.3,4 Acinetobacter junii is one species that is rarely reported to be a human infection. In this study, we presented a case of an isolated Acinetobacter junii in urine culture, which was identified in a patient who had a left nephrostomy tube placement with prior antibiotic use.

Case presentation

A 70-year-old female with a medical history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presented to the emergency room with abdominal pain, loss of appetite, fevers that reached as high as 103 °F as well as chills for one week. In the emergency room, the patient had moderate abdominal pain with flank pain. Her initial full blood count showed a white cell count of 36.4 × 109 cells/liter. Urinalysis showed more than 50 white blood cells per high-power field, positive leukocyte esterase, and negative nitrites. A computed tomography (CT) without contrast of the abdomen and pelvis revealed the left hydronephrosis with the presence of a 1 cm stone, likely causing obstruction as well as heterogeneity in the left upper pole parenchyma consistent with pyelonephritis. A urologist was consulted, who recommended a CT with contrast due to concerns for a possible renal abscess. The CT with contrast did not show any abscess, but demonstrated diffuse decreased enhancement, indicating stone obstruction. The left nephrostomy tube was placed. Microbiological studies revealed Candida glabrata in urine. The patient was started on voriconazole and zosyn. After two days, the patient's symptoms were resolved, and leukocytosis had down trended appropriately. The patient was discharged with the left nephrostomy tube in place along with ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for two weeks.

Two weeks after discharge, the patient was seen in the outpatient setting. She was planned to have a cystoscopy, left ureteroscopy, and laser lithotripsy for her left ureteral stone. She was also planned to place a stent at that time to remove her nephrostomy tube. She was instructed to repeat a urine culture approximately a week before the procedure. At that time, the patient had her urine culture done, which grew Acinetobacter junii (>100,000 colony-forming units of bacteria per milliliter of urine).

Discussion

A study was performed in Taiwan to identify isolates of Acinetobacter junii and to delineate the characteristics of this infection.5 Thirty-five infections with Acinetobacter junii were identified, and it mainly affected patients who had prior antimicrobial therapy, invasive procedures or malignancy.5 The similar situation was observed in this patient, who had nephrostomy tube inserted and prior exposure to antimicrobial agents. The placement of a left nephrostomy tube and the use of fluoroquinolones after the discharge are the risk factors for the growth of Acinetobacter junii at the outpatient setting.

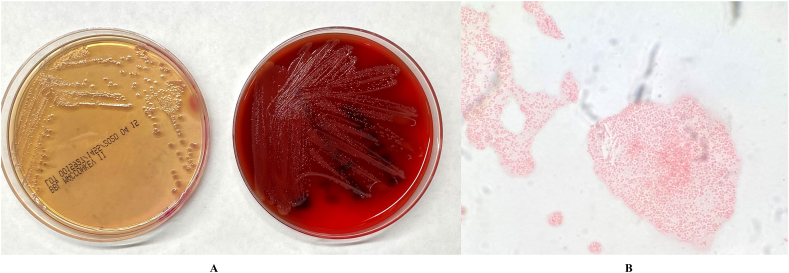

A urine specimen was submitted to the clinical microbiology laboratory for bacterial cultures. After 24 hours of incubation at 35 °C in 5% CO2, round-shaped and translucent colonies grew on sheep blood agar (tryptic soy agar containing 5% defibrinated sheep blood) and MacConkey agar plates (Fig. 1a). No growth was noted on Columbia CNA agar. Microscopic examination of a Gram-stained smear revealed small Gram-negative coccobacilli (Fig. 1b). The colonies on sheep blood agar are non-hemolytic. The isolate tested positive for catalase but tested negative for cytochrome oxidase and indole. Following primary isolation, the isolate was subjected to automated phenotyping using the VITEK 2 Gram-Negative Identification card (BioMérieux, Durham, NC, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions for use. Primary phenotypic testing identified the isolate as Acinetobacter junii.

Fig. 1.

A. Colonies of the isolate on sheep blood and MacConkey agars. Round-shaped and translucent colonies were observed. B. Microscopic examination of a Gram-stained smear revealed small Gram-negative coccobacilli.

Conclusion

In the study, we reported a clinical presentation in which the patient had required antibiotics and a procedure to be done for a urinary tract infection, and then the growth of Acinetobacter junii a few weeks after discharge. Although rare, our case study will help to further clarify the role of Acinetobacter junii as a human pathogen.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abdelrhman Abo-Zed: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft. Mohamed Yassin: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Resources, Writing - review & editing. Tung Phan: Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank the staff of the clinical microbiology laboratory at UPMC Mercy for help with initial isolation and characterization of the isolate.

References

- 1.Wong D., Nielsen T.B., Bonomo R., Pantapalangkoor P., Luna B., Spellberg B. Clinical and pathophysiological overview of acinetobacter infections: a century of challenges. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(1):409–447. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doughari H.J., Ndakidemi P.A., Human I.S., Benade S. The ecology, biology and pathogenesis of Acinetobacter spp.: an overview. Microb Environ. 2011;26(2):101–112. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.me10179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almasaud S.B. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology and resistance features. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2008;25(3):586–596. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohd Rani F., Rahman N.I., Ismail S. Acinetobacter spp. infections in Malaysia: a review of antimicrobial resistance trends, mechanisms and epidemiology. Front Microbiol. 2017;12(8):2479. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hung Y.T., Lee Y.T., Huang L.J. Clinical characteristics of patients with Acinetobacter junii infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2009;42(1):47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]