Abstract

Microsporum canis sensitive to itraconazole and terbinafine was isolated from two cats presented with generalized dermatophytosis and dermatophyte mycetoma. Itraconazole therapy was withdrawn through lack of efficacy in one cat (a Persian) and unacceptable adverse effects in the other (a Maine Coon). Both cats achieved clinical and mycological cure after 12–14 weeks therapy with 26–31 mg kg−1 terbinafine every 24 h per os (PO). Clinical signs in the Maine Coon resolved completely after 7 weeks treatment. Four weeks of therapy with additional weekly washes with a 2% chlorhexidine/2% miconazole shampoo following clipping produced a 98% reduction in the Persian cat's mycetoma, which was then surgically excised. Recurrent generalized dermatophytosis in the Persian cat has been managed with pulse therapy with 26 mg kg−1 terbinafine every 24 h PO for 1 week in every month. No underlying conditions predisposing to dermatophytosis were found in either cat despite extensive investigation. Terbinafine administration was associated with mild to moderate lethargy in the Persian cat, but no other adverse effects or changes in blood parameters were seen. To the best of the authors’ knowledge this is the first report of a dermatophyte mycetoma in a Maine Coon and of successful resolution of this condition in cats following terbinafine therapy.

Introduction

Dermatophytosis is an infection of skin, hair or nail with fungi of the genera Microsporum, Trichophyton and Epidermophyton. In cats, Microsporum canis usually causes a mild, self‐limiting infection and a low‐grade immune response, with multifocal alopecia and scaling, typically on the face, head and feet. 1 , 2 It is more common in Persian cats, possibly due to ineffective grooming of the long hair coat, the cutaneous microenvironment or immunological deficits. 1 , 2 Dermatophyte pseudomycetomas 1 and mycetomas 3 are subcutaneous dermatophyte infections with nodules, ulcers and draining sinus tracts, that are almost exclusively seen in Persian cats. 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 One case has been described in a domestic short hair (DSH), 8 and there are anecdotal reports in other DSH, British short hair and Burmese cats. Affected cats may exhibit no other clinical signs, focal to multifocal alopecia or generalized seborrheic dermatitis with moderate to severe scaling.

Dermatophyte pseudomycetomas are difficult to manage and the prognosis is poor. 2 The lesions often recur after surgical excision and there is little response to griseofulvin, ketoconazole or itraconazole. 7 One cat was cured after surgical excision followed by 10 mg kg−1 itraconazole every 24 h for 10 weeks 8 and three others after 8, 10 and 18 months therapy with 10–20 mg kg−1 itraconazole every 24 h alone. 4 , 5 , 6 One of the authors (NAM) has also seen a case resolve following surgical excision and 50 mg kg−1 griseofulvin every 24 h for 3 months. There is a single case report of a confirmed mycetoma in a Persian cat. 3 Itraconazole was ineffective (10–30 mg kg−1 every 24 h), but surgical resection was curative.

Terbinafine is an allylamine fungicidal agent that interferes with squalene epoxidase, disrupting ergosterol synthesis in the fungal cell wall leading to an accumulation of squalene. 9 , 10 It is highly lipophilic and keratinophilic, concentrating in body fat and keratinized tissues. Fungicidal concentrations can be detected in feline hair after 9 days treatment and detectable levels persist for at least 8 weeks following 14 days oral therapy (30–40 mg kg−1) every 24 h. 9 , 10 Terbinafine has a limited impact on mammalian cytochromes and there are few reported adverse effects or drug interactions. 9 , 10 The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against most dermatophytes, including M. canis, M. gypseum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes is low (MIC90 = 0.03 µg mL−1). 11 , 12 Several studies have reported efficacy in feline dermatophytosis at doses of 8.25–40 mg kg−1 for 14–120 days in naturally and experimentally affected cats, 10 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 although terbinafine is not licensed for animals. It is thought that lower doses are less effective and 30–40 mg kg−1 once daily is currently recommended. 9 , 13 , 17 There is only one report of the use of terbinafine to treat feline dermatophyte pseudomycetoma, in which a Persian cat failed to respond to 4 months of treatment at 14.5 mg kg−1 every 24 h followed by another 4 months at 30 mg kg−1 every 24 h. 7 The low cost, good safety profile and efficacy in other dermatophyte infections nevertheless make terbinafine a potentially useful treatment option worthy of further study. In contrast to the first case, this report describes successful management of dermatophyte mycetomas associated with terbinafine sensitive M. canis in two cats treated with 26–31 mg kg−1 terbinafine per os (PO) every 24 h.

Case reports

History

The first case was a 12‐year‐old, neutered male Persian cat with a 12‐month history of multifocal alopecia and scaling. Dermatophytosis was diagnosed by positive fungal growth and red colour change on dermatophyte test medium (Dermafyt™; Krusse UK Ltd, Leeds, UK) following inoculation with hair plucked from affected skin. There had been little response to multiple treatment cycles of 1–3 months duration with 5–10 mg kg−1 itraconazole (Sporanox®; Janssen‐Cilag, High Wycombe, UK) every 24 h PO in conjunction with topical 2% chlorhexidine/2% miconazole (Malaseb®; Dechra Veterinary Products, Shrewsbury, UK) two to three times weekly. The cat had not received systemic treatment for 3 weeks prior to referral but weekly topical therapy was ongoing. The second cat was a 12‐year‐old, neutered male Maine Coon originally referred for the investigation and management of obesity, but with a concurrent 1 month history of scaling and a single nodular mass. It had not received any topical or systemic antifungal therapy prior to presentation.

Clinical examination

On presentation both cats had generalized seborrhoea and scaling with 1–2 mm, greasy, non‐adherent scales, and multifocal partial alopecia with broken hairs, and single, soft, freely mobile and well‐circumscribed cutaneous nodules with draining sinus tracts and a haemorrhagic to purulent discharge. The Persian cat had a 2‐cm diameter mass in the dorsal midline just caudal to the thorax and the Maine Coon had a 3‐cm mass on the palmar aspect of the left mid‐antebrachium (Fig. 1). Both cats were depressed but clinical examination of the Persian cat was otherwise unremarkable. The Maine Coon had concurrent obesity (body weight 9.6 kg, body condition score 8/9), tachycardia (200 bpm) and bilateral elbow osteoarthritis.

Figure 1.

Dermatophyte mycetoma in a 12‐year‐old Maine Coon cat. The lesion is a 3‐cm in diameter, soft, freely mobile nodule on the palmar aspect of the left antebrachium.

Initial investigation

There was no fluorescence of the skin or hairs under Wood's lamp illumination in either cat. Cytology of the nodules (Rapi‐Diff II®; Bios Europe, Skelmersdale, UK) revealed numerous degenerate neutrophils, activated macrophages, multinucleate giant cells and fungal hyphae (Fig. 2). Examination of hair plucks revealed many broken hairs whose architecture was effaced by fungal hyphae and arthroconidia (Fig. 3). Inoculation of dermatophyte test medium (Dermafyt®) with toothbrush samples yielded positive fungal growth and a red colour change within 5 days at room temperature. Both isolates were later identified as M. canis following subculture onto Sabouraud's dextrose agar (Health Protection Agency Mycology Reference Laboratories, Bristol and Glasgow, UK). The isolates were found to be sensitive to itraconazole and terbinafine using in vitro broth dilution assays, 18 although MICs have not been reported by the laboratories.

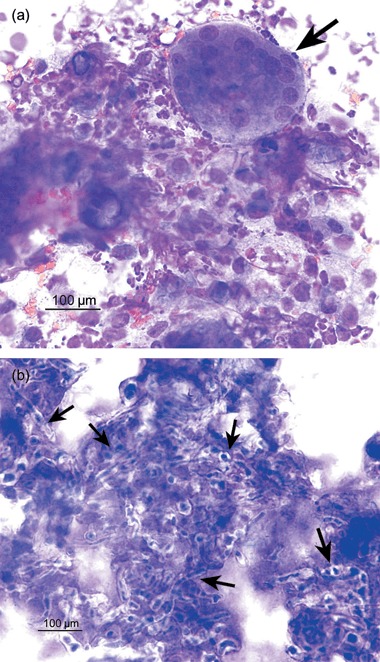

Figure 2.

Stained cytology (Rapi‐Diff II®) of a needle aspirate from the lesion in the Persian cat. Numerous degenerate neutrophils, activated macrophages, multinucleate giant cells (arrow 3a) and fungal hyphae (arrows 3b) are evident. Magnification ×400.

Figure 3.

Trichogram from the Maine Coon cat. The architecture of the affected hair has been effaced by fungal hyphae (open arrow) and arthroconidia (closed arrow). Magnification ×100.

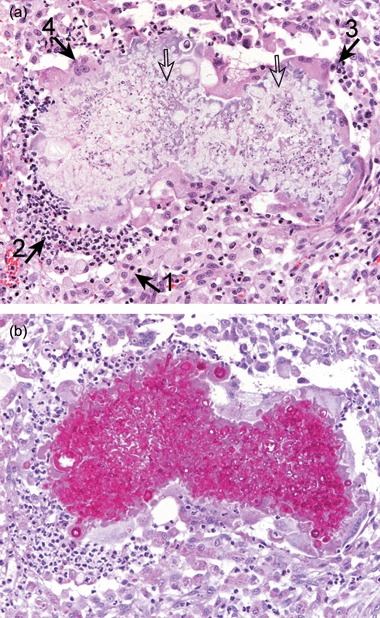

A skin sample was taken by biopsy with a 6‐mm punch from the Maine Coon's lesion under general anaesthesia. Histopathological examination (Fig. 4a) revealed that the normal cutaneous architecture was replaced by multilobular tissue with areas of gross necrosis, haemorrhage and ulceration. There was a multifocal, nodular dermatitis with numerous, large, coalescing foci of pyo‐granulomatous inflammation surrounding multiple, irregular, basophilic hyphae‐like elements in a sparse, granular, faintly eosinophilic matrix. These elements were strongly positive on periodic acid Schiff staining (Fig. 4b). Numerous activated macrophages, neutrophils, plasma cells and multinucleate giant cells were noted. There were severe infiltrates of activated macrophages and neutrophils underlying the ulcers. Microsporum canis with an identical sensitivity pattern to the isolates from hair plucks was cultured from fresh tissue taken at the time of biopsy. The owners of the Persian cat declined general anaesthesia and biopsy at this stage.

Figure 4.

Histopathology from the Maine Coon's lesion. There is a multifocal, nodular dermatitis with numerous, large, coalescing foci of pyo‐granulomatous inflammation surrounding multiple, irregular, faintly basophilic hyphae‐like elements (open arrows). The inflammatory infiltrate consists mainly of activated macrophages (closed arrow 1), with neutrophils (closed arrow 2), plasma cells (closed arrow 3) and multinucleate giant cells (closed arrow 4). A – haematoxylin and eosin (×200); B – periodic acid Schiff (×200).

There were no significant abnormalities on haematology and biochemistry, total T4, feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and feline coronavirus tests, radiography, ultrasonography, blood pressure, electrocardiography and echocardiography in either cat. Dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry found that body fat mass was 39.2% in the obese Maine Coon (reference range 15–25%). 19

A diagnosis of generalized dermatophytosis and dermatophyte mycetoma was made in each case on the basis of clinical signs, cytology, histopathology and fungal culture. No significant underlying conditions that could have predisposed to the fungal infections were evident.

Treatment

The cats were started on 26 mg kg−1 (Persian cat) and 27 mg kg−1 (Maine Coon; this later increased to 31 mg kg−1 as the cat lost weight) terbinafine (Lamisil®; Novartis AG) every 24 h PO with food. The Persian cat had already failed to respond to itraconazole, and the Maine Coon developed acute lethargy, vomiting and anorexia following a dose of 5 mg kg−1 every 24 h PO itraconazole for 3 days. The Persian cat was also clipped and treated with topical 2% chlorhexidine/2% miconazole once weekly at the owners request to reduce potential environmental contamination and risk to the other cat in the household. The owners of the Maine Coon chose not to perform topical therapy. This cat was treated concurrently with 0.05 mg kg−1 meloxicam (Metacam®; Boehringer Ingelheim, Bracknell, UK) every 48 h PO in food. The Persian cat was given its usual diet (Hills Feline Neutered Cat Mature fed ad libitum) and the Maine Coon was fed 70 g day−1 Royal Canin Obesity Management Diet.

Outcome and follow up

The Maine Coon's clinical signs resolved after 7 weeks of therapy, including resolution of the nodule. The Persian cat's coat was clinically normal after 4 weeks of therapy and the nodule had reduced in size to a 5‐mm diameter, firm, non‐ulcerated, freely mobile mass that was surgically removed with margins of 2 cm lateral and one facial plane deep to the nodule. Histopathological examination of the excised nodule revealed a multifocal, nodular dermatitis with coalescing foci of pyo‐granulomatous inflammation surrounding multiple, irregular, basophilic hyphae‐like elements. These elements were strongly positive on periodic acid Schiff staining. The inflammatory infiltrate consisted of activated macrophages, neutrophils, plasma cells and occasional multinucleate giant cells. The foci were surrounded by irregular fibrovascular tissues. The histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of dermatophyte mycetoma and suggested that the lesion had been completely removed with clear margins of healthy tissue. The location of the mycetoma in the Maine Coon made radical surgery initially impractical and by the time this was considered, the lesion had completely resolved.

Mycological cure (three consecutive negative toothbrush cultures on dermatophyte test medium at 7–14 day intervals) was achieved after 14 weeks in the Persian cat and 12 weeks in the Maine Coon. Clinical signs of generalized seborrhoea and scaling, however, recurred once systemic therapy with terbinafine stopped in the Persian cat. Further fungal culture revealed M. canis with the same antifungal sensitivity pattern as before. The condition has been controlled by pulse dosing with 26 mg kg−1 terbinafine once daily for 7 consecutive days every month to date (follow up = 36 months), following data indicating that therapeutic levels of terbinafine persist in the hair for several weeks following doses of 30–40 mg kg−1 PO. 9 , 10 The Maine Coon has had no recurrence of clinical signs (follow up = 25 months).

There were no significant haematological or biochemical abnormalities in either cat during therapy. The Persian cat has suffered mild to moderate lethargy during the 7 day dosing period of its pulse therapy cycle, but this has not been associated with other clinical findings or abnormalities on haematology and biochemistry. No other adverse effects were noted during therapy with terbinafine in either cat. Zoonotic dermatophytosis was not seen in the in‐contact humans in either case. Another Persian cat that shared the same household with the affected Persian cat has not developed any clinical signs or positive toothbrush cultures to date.

Discussion

This report describes two cases of dermatophyte mycetoma that responded to systemic treatment with 26–31 mg kg−1 terbinafine once daily for 12–14 weeks. Both lesions were differentiated from pseudomycetomas according to the criteria used to confirm the first published case of a feline dermatophyte mycetoma, 3 including the absence of strongly eosinophilic Hoeppli–Splendore material, numerous hyphal elements within the granules and cement‐like granule matrix.

The Maine Coon cat was cured after 7 weeks and the lesion in the Persian cat was reduced by approximately 98% over 4 weeks before surgical removal without recurrence. In both cases, as is widely reported, mycological cure took much longer to achieve. 2 , 17 The reason for the difference between these findings and the previous failure to achieve resolution in a cat with terbinafine 7 is unclear. Although MICs were not provided to the authors, the M. canis isolates in this study were reported to be sensitive to terbinafine in a standard broth dilution assay; 18 in vitro sensitivity of the M. canis in the earlier case study was not reported. However, a recent study found that in vitro MICs for terbinafine against naturally occurring M. canis isolates from infected cats were very variable, and while all treated cats were cured, those with more resistant isolates took longer to reach complete mycological cure. 16 Penetration of terbinafine into the mycetoma may, however, be more relevant to clinical outcome than in vitro sensitivity tests. In vitro antifungal sensitivity testing of dermatophyte isolates from animals, furthermore, is not a standardized procedure.

The very precise temporal association with treatment firmly implicates terbinafine as the cause of the lethargy during maintenance treatment in the Persian cat, although this was never severe enough to warrant withdrawal of therapy. Previously reported adverse effects of this drug include mild to moderate vomiting in 8–40% of treated cats 10 , 13 , 14 and erythema, pruritus and urticaria in two of 10 cats in one study. 9

To the authors’ knowledge this is the first reported example of a dermatophyte mycetoma in a Maine Coon and only the second case in a Persian cat. 3 Most previous cases have been pseudomycetomas in Persian cats. 1 , 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Persian cats and Maine Coons are both long‐haired breeds, although they are not thought to be closely related. It has been suggested, though not proven, that dermatophyte pseudomycetomas are associated with breed‐related immunodeficiency or an aberrant immune response to dermatophytes. 1 , 2

The reason for the failure to achieve permanent clinical and mycological cure in the Persian cat with systemic and topical therapy is still obscure. Eventual self‐cure of dermatophytosis (but not mycetoma or pseudomycetoma) associated with cell‐mediated immunity is considered normal in cats, 1 , 2 and there was no evidence of any underlying disease or immunosuppression in either cat and both have remained systemically healthy to date. Persian cats are predisposed to chronic and recurrent dermatophytosis, possibly due to ineffective grooming, the cutaneous microenvironment or immunological deficits 1 , 2 However, interestingly, another Persian cat in the same household had negative fungal cultures throughout the entire period suggesting that the affected cat had unique predisposing factors or there was undetected residual infection in the skin or hair following the initial course of treatment.

The outcome following itraconazole therapy with or without surgery has been inconsistent. 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 The M. canis isolates were reported to have in vitro sensitivity to itraconazole, which maintains therapeutic concentrations in the skin and hair for at least 2 weeks after the final dose. 20 It is unlikely, however, that residual itraconazole contributed to the clinical response in these cases: the Persian cat had not responded to 12 months of intermittent therapy and treatment ceased 3 weeks before presentation; and the Maine Coon only had 3 days treatment before adverse effects necessitated a change in therapy.

It is unlikely that clipping the coat and topical therapy influenced the response to treatment. The Persian cat had received intermittent topical therapy for 12 months before presentation without improvement, and the Maine Coon, which did not receive topical therapy, was slightly quicker to respond. Clipping is a controversial measure that can facilitate topical therapy and remove infected hairs, reducing the pathogenic load and environmental contamination, but it can also result in skin trauma and disseminated infection. 2 Topical therapy can reduce time to clinical and mycological cure, but is unlikely to effect a cure by itself. 2 , 21 , 22

These case reports are non‐controlled and non‐blinded, and could therefore suffer from selection, inclusion, performance and detection bias. These cases therefore only provide preliminary evidence for the efficacy of terbinafine in treating feline dermatophyte mycetoma and pseudomycetoma, and this should be tested with larger case cohorts.

Résumé Microsporum canis sensible à l’itraconazole et la terbinafine a été isolé de deux chats présentés pour dermaophytose généralisée et mycétome dermatophytique. L’itraconazole a été stoppé après manque d’efficacité dans un cas (un Persan) et pour effets secondaires inacceptables pour l’autre (un Maine Coon). Les deux chats ont été guéris cliniquement et mycologiquement après 12–14 semaines avec 26–31 mg/kg de terbinafine q24h per os (PO). Les signes cliniques chez le Maine Coon ont totalement disparu après sept semaines de traitement. Quatre semaines supplémentaires avec association de lotions hebdomadaires avec un shampooing de 2% chlorhexidine/2% miconazole après tonte a permis une diminution de 98% des lésions chez le Persan, suivi d’une exérèse chirurgicale. La dermatophytose généralisée du Persan a été traitée avec une thérapeutique pulsée de 26 mg/kg de terbinafine q24h PO une semaine par mois. aucune cause sous jacente n’a été trouvée pour les deux chats malgré une recherche extensive. L’administration de terbinafine a provoqué une léthargie modérée chez le Persan, mais aucun autre effet secondaire ou modification des paramètres sanguins n’a été observée. A la connaissance des auteurs, il s’agit de la première description de mycétome chez un Maine Coon et du rapport de l’efficacité de la terbinafine dans cette indication.

Resumen Se aislóMicrosporum canis sensible a itraconazol y terbinafina en dos gatos que se presentaron con dermatofitosis generalizada y micetoma dermatofítico. El tratamiento con itraconazol fue interrumpido debido a la falta de eficacia en un gato (un Persa) y efectos adversos inaceptables en el otro (un gato Maine Coon). Ambos gatos obtuvieron cura clínica y micológica tras 12–14 semanas de tratamiento con 26–31 mg/kg de terbinafina q24 por via oral (PO). Los signos clínicos en el gato Maine Coon resolvieron por completo tras siete semanas de tratamiento. Cuatro semanas de tratamiento adicional con lavados semanales con un champú con 2% de clorhexidina/2% miconazol tras rasurado produjo una reducción de un 98% en el micetoma del gato Persa que después se extirpó quirurgicamente. Dermatofitosis generalizada recurrente en el gato Persa habia sido controlada con terapia en pulso con 26 mg/kg de terbinafina q24 PO durante una semana de cada mes. No se descubrieron otras condiciones que pudieran haber predispuesto a la dermatofitosis en ninguno de los gatos. La administración de terbinafina se asoció con letargia leve a moderada en el gato Persa, pero no se observaron otros efectos adversos o cambios en los parámetros sanguineos. Según nuestro conocimiento este es el primer caso reportado de un micetoma dermatofítico en un gato Maine Coon y de la resolución con éxito de esta condición en gatos tras la administración de terbinafina.

Zusammenfassung Microsporum canis, welcher sensitiv auf Itraconazol und Terbinafin war, wurde von zwei Katzen isoliert, die mit einer generalisierten Dermatophytose und einem Dermatophyten Mycetom präsentiert wurden. Die Therapie mit Itraconazol wurde bei einer Katze (einer Perserkatze) abgesetzt, da sie unwirksam war und bei der anderen Katze (einer Maine Coon Katze) wegen inakzeptablen Nebenwirkungen. Bei beiden Katzen wurde nach 12–14 Wochen der Behandlung mit 26–31 mg/kg Terbinafin alle 24 Stunden per os (PO) eine klinische und mykologische Heilung erzielt. Die klinischen Symptome bei der Main Coon verschwanden nach einer Behandlungsdauer von sieben Wochen zur Gänze. Eine vier Wochen lange Therapie mit zusätzlichen wöchentlichen Bädern mit einem 2% Chlorhexidin/2% Mikonazol Shampoo nach der Schur bewirkte eine 98% ige Reduktion der Größe des Mycetoms bei der Perserkatze, welches danach chirurgisch entfernt wurde. Die wiederkehrende generalisierte Dermatophytose der Perserkatze wurde mittels Pulstherapie mit 26 mg/kg Terbinafin alle 24 Stunden PO für eine Woche eines jeden Monats kontrolliert. Es wurden trotz intensiver Untersuchungen bei keiner der Katzen zugrunde liegende Ursachen gefunden, die für eine Dermatophytose prädisponiert hätten. Die Verabreichung von Terbinfin bewirkte bei der Perserkatze eine leichte bis moderate Lethargie, aber es wurden keine weiteren Nebenwirkungen oder Veränderungen bei den Blutparametern gesehen. Nach bestem Wissen des Autors handelt es sich hierbei um den ersten Bericht eines Dermatophyten Mycetoms bei einer Maine Coon Katze sowie die erfolgreiche Behandlung dieses Zustandes bei Katzen mit Terbinafin Therapie.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of Abbey Veterinary Services, and the Bristol and Glasgow Health Protection Agency Mycology Reference Laboratories for performing the histopathology, fungal culture and sensitivity tests, respectively.

Sources of funding This study was self‐funded. TJ Nuttall has received lecture fees from Janssen Animal Health and Royal Canin, AJ German is in receipt of funding from Royal Canin, and TJ Nuttall and NA McEwan are in receipt of funding from VetXX Ltd (now Dechra Veterinary Products plc). Conflict of interest None of the authors has financial or other interests in any of the products mentioned in this report.

References

- 1. Sparkes AH, Gruffydd Jones TJ, Shaw SE, Wright AI, Stokes CR. Epidemiological and diagnostic features of canine and feline dermatophytosis in the United Kingdom from 1956 to 1991. Veterinary Record 1993; 133: 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moriello KA, DeBoer DJ. Feline dermatophytosis. Veterinary Clinics of North America – Small Animal Practice 1995; 25: 901–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kano R, Edamura K, Yumikura H et al Confirmed case of feline mycetoma due to Microsporum canis . Mycoses 2008; online early publication doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Medleau L, White Weithers NE. Treating and preventing the various forms of dermatophytosis. Veterinary Medicine 1992; 87: 1096–100. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Medleau L, Rakich PM. Microsporum canis pseudomycetomas in a cat. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 1994; 30: 573–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pin D, Carlotti DN. A case of dermatophytic mycetoma caused by Microsporum canis in a Persian cat. Pratique Médicale et Chirurgicale de L’animal de Compagnie 2000; 35: 105–12. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bond R, Pocknell AM, Toze CE. Pseudomycetoma caused by Microsporum canis in a Persian cat: lack of response to oral terbinafine. Journal of Small Animal Practice 2001; 42: 557–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guaguère E, Bourdoiseau G. Microsporum canis mycetoma and generalised dermatophytosis in a cat infected by the feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). Pratique Médicale et Chirurgicale de L’animal de Compagnie 2000; 35: 113–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Foust AL, Marsella R, Akucewich LH et al Evaluation of persistence of terbinafine in the hair of normal cats after 14 days of daily therapy. Veterinary Dermatology 2007; 18: 246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kotnik T, Erzen NK, Kuzner J, Drobnic‐kosorok M. Terbinafine hydrochloride treatment of Microsporum canis experimentally‐induced ringworm in cats. Veterinary Microbiology 2001; 83: 161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hofbauer B, Leitner I, Ryder NS. In vitro susceptibility of Microsporum canis and other dermatophyte isolates from veterinary infections during therapy with terbinafine or griseofulvin. Medical Mycology 2002; 40: 179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nardoni S, Millanta F, Mancianti E. In vitro sensitivity of two different inocula of Microsporum canis versus terbinafine. Journal de Mycologie Medicale 2000; 10: 148–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kotnik T. Drug efficacy of terbinafine hydrochloride (Lamisil®) during oral treatment of cats, experimentally infected with Microsporum canis . Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series B – Infectious Diseases and Veterinary Public Health 2002; 49: 120–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mancianti F, Pedonese F, Millanta F, Guarnieri L. Efficacy of oral terbinafine in feline dermatophytosis due to Microsporum canis . Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 1999; 1: 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kotnik T, Cerne M. Clinical and histopathological evaluation of terbinafine treatment in cats experimentally infected with Microsporum canis . Acta Veterinaria Brno, 2006; 75: 541–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Millanta F, Pedonese F, Mancianti F. Relationship between in vivo and in vitro activity of terbinafine against Microsporum canis infection in cats. Journal de Mycologie Médicale 2000; 10: 30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moriello KA. Treatment of dermatophytosis in dogs and cats: review of published studies. Veterinary Dermatology 2004; 15: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards . Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi; Approved Standard. NCCLS document M38‐A. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raffan E, Holden SL, Cullingham F, Hackett RM, Rawlings JM, German AJ. Standardized positioning is essential for precise determination of body composition using dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry in dogs. Journal of Nutrition 2006; 136: 1976S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vlaminck KMJA, Engelen MACM. Itraconazole: a treatment with pharmacokinetic foundations. Veterinary Dermatology 2004; 15: 8. [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeBoer DJ, Moriello KA. Inability of two topical treatments to influence the course of experimentally induced dermatophytosis in cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1995; 207: 52–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paterson S. Miconazole/chlorhexidine shampoo as an adjunct to systemic therapy in controlling dermatophytosis in cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice 1999; 40: 163–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]