Summary

Respiratory infections, especially those of the lower respiratory tract, remain a foremost cause of mortality and morbidity of children greater than 5 years in developing countries including Pakistan. Ignoring these acute‐level infections may lead to complications. Particularly in Pakistan, respiratory infections account for 20% to 30% of all deaths of children. Even though these infections are common, insufficiency of accessible data hinders development of a comprehensive summary of the problem. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence rate in various regions of Pakistan and also to recognize the existing viral strains responsible for viral respiratory infections through published data. Respiratory viruses are detected more frequently among rural dwellers in Pakistan. Lower tract infections are found to be more lethal. The associated pathogens comprise respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus (HMPV), coronavirus, enterovirus/rhinovirus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, and human bocavirus. RSV is more dominant and can be subtyped as RSV‐A and RSV‐B (BA‐9, BA‐10, and BA‐13). Influenza A (H1N1, H5N1, H3N2, and H1N1pdm09) and Influenza B are common among the Pakistani population. Generally, these strains are detected in a seasonal pattern with a high incidence during spring and winter time. The data presented include pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and influenza. This paper aims to emphasise the need for standard methods to record the incidence and etiology of associated pathogens in order to provide effective treatment against viral infections of the respiratory tract and to reduce death rates.

Keywords: Acute viral respiratory infections, Bronchiolitis, children, developing countries, enteroviruses, epidemiology, etiology, HMPV, incidence, Influenza, Pakistan, Pneumonia, rhinoviruses, RSV, Viral respiratory infections

Abbreviations

- ALRI

Acute lower respiratory tract infection

- ARI

Acute respiratory infections

- HMPV

Human metapneumovirus

- LRTI

Lower respiratory tract infection

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus

- RTI

Respiratory tract infection

- RT‐PCR

Real‐time polymerase chain reaction

- URTI

Upper respiratory tract infection

1. INTRODUCTION

Respiratory tract infections (RTI) can be defined as the infection in any part of the respiratory tract. RTIs can be further classified as upper tract respiratory infections (UTRI) and lower tract respiratory infections (LTRI). The infections of the upper tract are most common and include rhinitis, croup, sinusitis, pharyngitis, epiglottitis, and laryngitis. The infections of the lower tract are more fatal and include pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, and influenza.1 Acute respiratory infections (ARI) are tremendous cause of health problems and mortality in emerging countries.2 In South Asia, 48 of every 1000 children died before the age of five.3 Pakistan is currently ranked as the sixth most populous country with the population of 199 million.4 It is estimated that about 20% to 30% of all deaths of children under 5 years of age are because of respiratory infections in Pakistan.5 This paper comprises an introduction to viral respiratory infections, common genotypes of viruses associated with respiratory infections in different regions of Pakistan, and data from surveys led from 2007 onwards.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Literature search strategy

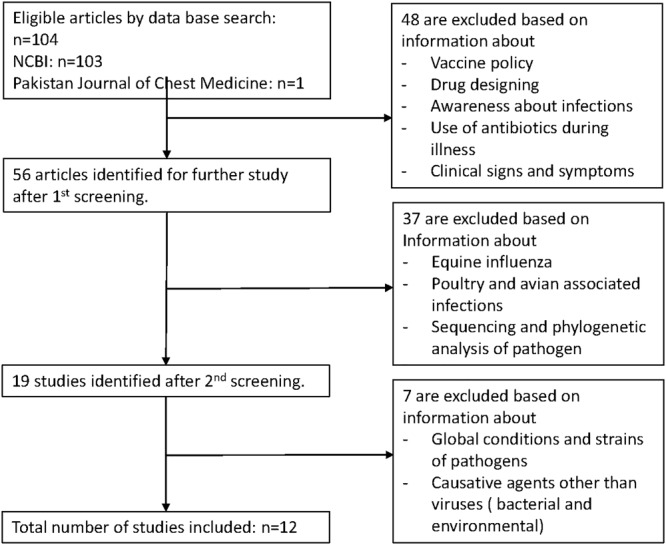

A literature review was conducted to identify the published studies having data of viral respiratory infections in Pakistan. To perform the literature review, we searched the PubMed database for articles published between 2000 and 2018, using the key terms “viral respiratory infections,” “influenza,” “pneumonia,” “bronchiolitis,” “common cold,” combined with the terms “morbidity,” “mortality,” “fatality,” “epidemiology,” “etiology,” “genotypes,” “developing countries,” “South Asia,” “Pakistan,” “prevalence,” “incidence” for articles published in English. Titles and abstracts of publications were reviewed, and articles containing data of viral respiratory infections from Pakistan were included. Studies were evaluated by all team members (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the process of literature selection for the review

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies were study of respiratory infections caused by viruses, data from Pakistan, publications from the year 2000 onwards in English language, and there was no restriction on subject age and gender (Figure 1). The exclusion criteria were bacterial infections, information about countries other than Pakistan, and infections of non‐human species.

3. RESULTS

We initially identified 104 electronic articles from NCBI and Pakistan Journal of Chest Medicine that met our original search strategy. Figure 1 identifies the strategy used to screen articles for this review. After obtaining and evaluating each article, 12 articles were incorporated, and 92 were excluded. Out of 12 included articles, seven (including four for bronchiolitis and one for influenza) were about viral strains which were responsible for causing pneumonia in children and in older adults, and five were about surveillance and epidemiology of viral strains that cause influenza (Table 1). The excluded articles were related to vaccine policies, drug designing for eradication purpose of infection, raising awareness, clinical symptoms of infections, infections caused by bacterial and environmental influences, and had information about the global status of infections.

Table 1.

Distribution of viral pathogens responsible for RTIs across Pakistan, studies from 2000 to 2018

| Reference | Year of Publication | Study Duration | Geographical Location | Infection Studied | Cases Studied | Age Group | Viral Genotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 2000 | November 1986‐March 1988 | Rawalpindi, Islamabad | ALRIs | 553 out of 1492 | >60 months | RSV, parainfluenza 3, influenza A&B, adenovirus |

| 17 | 2005 | October 1999‐April 2000 | Rawalpindi, Islamabad | Pneumonia, bronchiolitis | 80 infected out of 391 | 2 months‐3 years | RSV |

| 27 | 2008 | October‐December 2008 | Peshawar (KPK) | Influenza | 5 (4 confirmed, 1 asymptomatic) | 22‐33 years | Influenza A/H5N1 |

| 28 | 2011 | 2006‐07 | Northwest Frontier Province (KP) | Influenza | 20 (4 confirmed, 7 likely, 9 possible) | 25‐35 years | Influenza A/H5N1 |

| 29 | 2012 | 2009‐10 | Not specified | Influenza | 497 out of 1287 | Not specified | Influenza A/(H1N1)pdm09 (n = 262), B (n = 180), A(H3N2) (n = 6), non‐typed influenza A viruses (n = 49) |

| 19 | 2013 | 17 August 2009‐16 September 2011 | Karachi | Pneumonia (n = 13), bronchiolitis (n = 4), URTI (n = 3), Asthma (n = 2), other syndromes (n = 1) | 812 enrolled, 27 positive, 4 deaths | >5 year | Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 (n = 27) (H3 in 7 children) 1 untyped |

| 8 | 2013 | 2011‐2012 | Gilgit‐Baltistan | ARIs | 80 out of 105 | <2 years | RSVA genotype‐A1/GA2 (n = 71), RSVB genotype‐BA (n = 04), influenza A (n = 05), HMPV (n = 04) |

| 12 | 2013 | Jan 2008‐ Dec 2011 | Islamabad, KP, Punjab and Baluchistan | ILI, SARI | 1489 out of 6258 | ≥65 | Influenza A (n = 1066; A/H1N1 25, A/H3N2 169 A(H1N1)pdm09 872), influenza B (n = 423) |

| 18 | 2013 | Nov 2010‐Sep 2011 | Karachi | Pneumonia, influenza | 169 | 6 weeks‐ 2 years | HMPV (n = 24), influenza A/H1N1 (n = 08), non‐typed A (n = 01), RSV (n = 30) |

| 9 | 2017 | Mar 2011‐April 2012 | Islamabad | ALRI, Pneumonia, UTRI‐bronchiolitis | 117 out of 155 | 6 weeks‐2 years | RSVA (n = 69), RSVB (n = 35), influenza A (n = 38), influenza B (n = 11), HMPV (n = 08), adenovirus (n = 13) [single virus (n = 67), 2 pathogens (n = 45), up to 3 (n = 5) cases] |

| 6 | 2016 | Not specified | Rawalpindi | LTRI | 72 out of 150 | <10 years | Parainfluenza virus 3 (n = 27), RSV (n = 27), influenza A (n = 15), influenza B (n = 3) |

| 20 | 2016 | Oct 2015‐Feb 2016 | Peshawar | Pneumonia | 37 out of 145 | 4 < 20 years > 33 | Influenza A/H1N1 |

| 7 | 2016 | Oct 2011‐June 2014 | Matiari (Sindh) | Pneumonia | 204 out of 692 | ˂2 years | RSV (n = 13), influenza B (n = 04), HMPV (n = 05), enterovirus/rhinovirus (n = 119), human coronavirus (n = 21), parainfluenza virus (n = 33), adenovirus (n = 08), human Boca virus (n = 01) |

| 10 | 2017 | Aug 2009‐June 2012 | Karachi | ARI, Pneumonia (n = 87), bronchiolitis (n = 89), asthma (n = 31), URI (n = 20) | 227 out of 1150 | ˂5 years | RSV |

| 16 | 2017 | Oct 2010‐April 2013 | Not specified | ALRI; ILI (n = 295), SARI (n = 177) | 472 out of 1941 | <5 years | RSVA (n = 367), RSVB genotype‐BA (n = 105) |

| 30 | 2017 | Dec 2015‐Jan 2016 | North West Pakistan | Influenza | 11 out of 37 | 40.46 (±15.27) years | Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 |

| 11 | 2018 | Aug 2009‐June 2012 | Karachi | ARI Pneumonia (n = 29), bronchiolitis (n = 18), asthma (n = 19), URI (n = 10) | 84 out of 1150 | <5 years | HMPV |

3.1. Included studies

The characteristics of the articles included in this systematic review of the literature are shown in Table 1.

3.2. Etiology

Viral etiology of LTRIs includes respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and parainfluenza virus 3 among Pakistani population.6 According to a study, enterovirus/rhinovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, and human Bocavirus were also found to be associated with respiratory infections particularly with viral pneumonia.7 RSV was labeled as a dominant causative agent of lower RTI in a research conducted in a tertiary care healing center of Gilgit Baltistan where RSV genotypes were detected in 75 out of 105 children <2 years of age suffering from ARIs during the winter season from December 2011 to March 2012. The 75 identified strains were typed as 71 strains of RSV‐A and four strains of RSV‐B.8 Another study employed 1941 samples, analyzed by real time polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) for RSV infection. Twenty four percent of samples were positive, and out of these positive, 22% were subtyped RSV‐B. Three genotypes of RSV‐B—BA‐9, BA‐10, and BA‐13—were isolated.9 Throat swabs were tested by RT‐PCR. Nineteen percent of cases were identified as RSV associated infections. RSV appeared to be more incident from August to October and highest in September. Susceptibility increased in rainy seasons.10 HMPV was detected in 7% of the cases in the above scenario, most of which were children under 1 year of age.11

The results of a surveillance study conducted during January 2008 and December 2011 determined influenza A as a causative agent of infection in a great number of people. A total of 6258 samples were analyzed by RT‐PCR assay, out of which 1489 samples were positive for influenza virus. Seventy‐two percent of which were influenza A, and 28% were influenza B. Among influenza A, three strains were identified. These strains were A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and A/H1N1pdm09.12 The results of another hospital‐based study confirmed the viral association with ALRI. The study was conducted in two hospitals of twin cities of Pakistan from November 1986 to March 1988. A total of 1492 nasopharyngeal aspirates were analyzed. The patients enrolled were presented with wheezing, cough, high breathing rate, and chest retraction. Results indicated the viral etiology in 37% of the cases, of which 33% of the total (and 89% of cases with viral etiology) were resulted positive for RSV. Other pathogens identified were parainfluenza 3, influenza A&B, and adenovirus. RSV also showed peak activity in cold and showery weather from December to February.13

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an ARI of the lower tract particularly the lungs. It is a fatal disease and can be viral, bacterial, or fungal. Viral pneumonia is commonly caused by RSV. Children under 5 years of age are more susceptible for pneumonia which was responsible for killing 920 136 (16%) children worldwide in 2015.14 Every year, almost 200 million cases of viral pneumonia occur, which affects children and adults equally.15 Common symptoms include cough, high‐temperature fever, wheeze, runny nose, and nasal congestion.9, 16 In 2017, UNICEF assessed 64% of children under age 5 indicating the symptoms of pneumonia in Pakistan.3

A study employing 391 cases of pneumonia showed the dominant behavior of RSV. It was conducted in Armed Forces Institute of Pathology from October 1999 to April 2000. Nasopharyngeal aspirates were collected from different pediatric units of Rawalpindi and Islamabad for analysis purpose. Eighty samples showed positivity for RSV with a clear peak activity in winter season.17 Another study conducted in Karachi from August 2009 to September 2011 reported 13 out of the 27 cases diagnosed with pneumonia which were positive for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09.18 One more study was conducted during November 2010 and September 2011 in Karachi, Pakistan. All of the children were admitted because of severe pneumonia, out of which 18% were diagnosed with viral pneumonia. Throat swabs were analyzed using RT‐PCR. Out of 169 children, 24 were detected with human metapneumovirus (HMPV), 9 with influenza A and 30 with RSV. Nine out of 169 admitted patients (aged 6 weeks to 2 years) with pneumonia were diagnosed positive for influenza A virus, out of which eight tested positive for H1N1 strain.19 According to a descriptive study from Lady Reading Hospital Peshawar, conducted during October 2015 and February 2016, out of 145 suspected cases, 37 were selected on the basis of various factors including age, gender, residence, hypoxia, pregnancy status, symptoms, positivity to PCR, fatality, ventilation support, and radiological findings. All of the cases were tested positive for H1N1 strain of influenza A.20 In 2016, one more study was conducted in the rural district of Matiari in Sindh, Pakistan. Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from identified cases of pneumonia. The analysis was done by using multiplex RT‐PCR. A total of 817 newborns were enrolled and 49 enrolled for 2 years; 77.8% (179/230) were positive for any of the following: RSV, influenza virus, HMPV, enterovirus/rhinovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, and human Bocavirus. The incidence of 11.9 per 100 children was observed for laboratory‐confirmed viral pneumonia; 51.7% of patients were detected with Enterovirus/rhinovirus, 8.3% with parainfluenza virus type 3, and 5.7% with RSV.7 Bashir and colleagues conducted a detailed study during March 2011 to April 2012 in two hospitals of Islamabad, Pakistan; 75% of cases among children aged less than 2 years were viral. Samples were analyzed using RT‐PCR. Major pathogens included 44% RSV‐A, 23% RSV‐B, 24.5% influenza A, 7% influenza B, 8.4% adenovirus, and 5.2% HMPV. RSV‐A and RSV‐B association was detected more commonly during 2 to 6 months of age, while influenza A was estimated as more common in 2.1 to 6‐month age group.9 RSV association with kids between the ages of one and 5 years old suffering from pneumonia and asthma was the most widely recognized finding of a 3‐year study conducted in Karachi from August 2009 to June 2012. In older children between the ages of one and 5 years old, pneumonia and asthma were the most widely recognized findings.10 In another study conducted by the group, the cases were characterized by pneumonia followed by bronchiolitis.11

4.2. Bronchiolitis

Bronchiolitis is an acute viral infection, characterized by the inflammation of bronchioles. It is a contagious infection of the lower respiratory tract, and incidence is high during the winter season. It is more common in immuno‐compromised individuals.21 Key pathogens associated with the condition of bronchiolitis include influenza virus, RSV, coronavirus, adenovirus, and rhinovirus.22

A study conducted in Armed Forces Institute of Pathology from October 1999 to April 2000 estimated the association of RSV with bronchiolitis in 20% of the cases. A total of 391 nasopharyngeal aspirates from Rawalpindi and Islamabad were analyzed using direct immunofluorescence. Children aged between 2 months and 3 years were enrolled for study. Results pointed out the significant increase of about 50% in activity of RSV in winter.17 Another study conducted in Agha Khan University Hospital, Karachi identified 27 positive cases for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09. This study was conducted from August 2009 to September 2011. Total of 812 children were enrolled, out of which 3.3% resulted positive with viral etiology. Four of the admissions diagnosed were of bronchiolitis. The samples were tested using RT‐PCR. The results of this study estimated 15% fatality rate.18 Association of key viral pathogen RSV and influenza virus was identified in children under 2 years of age hospitalized with bronchiolitis during March 2011 and April 2012 in Islamabad, Pakistan. Major pathogens involved were RSV‐A, RSV‐B, influenza A, influenza B, adenovirus, and HMPV. Cases involving dual and even multiple pathogens were also identified.9 Children less than 5 years of age conceded with intense respiratory contaminations (ARI) were enlisted for another study conducted at Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi. This study spanned the duration of 3 years from August 2009 to June 2012. RT‐PCR was done for RSV testing by using throat swabs. Out of 1150 children selected, RSV was recognized among 223 (19%). The most noteworthy rate of RSV identification was in infants under 3 months of age (48/168, 29%), which represented 22% of all RSV distinguished. Most normal determination in RSV positive babies (<12 months of age) was bronchiolitis trailed by pneumonia whereas in other study, 7% (84 out of 1150) of the cases were identified with the presence of HMPV, 67% (56 out of 84) of which were children under 1 year of age, and these cases were characterized by bronchiolitis trailed by pneumonia.10, 11

4.3. Influenza

Influenza or flu is an acute and contagious viral infection of the respiratory tract.23 Influenza viruses are RNA viruses belonging to family orthomyxoviridae. Influenza A and influenza B are the two key viral strains blamable for inflicting infection, a transmissible respiratory illness in humans. Additionally, Zika virus infection also seems to be the reason behind the influenza‐like illness in certain cases.24 In 2009, the rapid worldwide spread of an emerging re‐assorted strain, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, was detected in the USA along with Mexico. This condition pushes WHO to raise the pandemic alert. This pandemic mainly affected 214 countries and killed 18 449 people.25 In 2008, about 28 000 to 111 500 deaths of children aged under 5 years due to influenza‐related infections were estimated around the globe. In developing countries, that ratio is around 99%.26

The first human case of influenza A/H5N1 virus infection from Pakistan was restricted to a cluster of four brothers. Evidence of these cases suggested the occurrence of the transmission chain. It began with a poultry culling operation that was carried out in late October 2007. It was performed in the response to a laboratory‐confirmed outbreak in a poultry breeding farm located near Abbottabad in the then North West Frontier Province (now KhyberPakhtun Khawa). Thirteen people performed in this operation. One of those was a 25‐year‐old Livestock Production officer, who became the index case. This was the initial transmission that was from poultry to human. This was followed by next three generations of human to human transmission because of long and intimate contact among brothers.27

In another evidence of human to human spread in KhyberPakhtun Khawa, 20 positive cases for A/H5N1 influenza were identified in October 2007. One subject had poultry infected H5N1 virus, other eight patients got an infection by human‐to‐human‐transmission. However, 12 patients did not show any epidemiological relation with group of other eight patients.28 In June 2009, the first case with A (H1N1)pdm09 influenza infection was documented. Between 27th April 2009 and 31st August 2010, 1287 suspected cases were analyzed by means of RT‐PCR. Influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 were detected in 262 samples from Pakistan. While others exhibited combinations of influenza A (unknown type), influenza B, and influenza A/H3N1.29 According to another study conducted in a tertiary care hospital throughout December 2015 until the end of January 2016, patients with cough, nasal congestion, wheezing, and chest pain were likely to develop complications of RTI and were suspected for influenza A/H1N1 and severe acute respiratory illness (SARI). Samples from 36 patients were obtained and analyzed by qPCR. Out of 11 patients, seven were confirmed with the presence of influenza A/H1N1pdm09 strain. Three patients died because of further respiratory complications.30

5. CONCLUSION

The results of literature review acknowledged numerous gaps in the availability of data. Reportedly, lower tract infections have high fatality rate. Particularly in the countryside communities of Pakistan, the occurrence of respiratory viruses is more periodic and common especially in children under 2 years of age. Evaluation of reported data has identified several pathogens involved in causing respiratory infections. Pathogens involved include RSV, HMPV, enterovirus/rhinovirus, coronavirus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, and human Bocavirus. Especially, RSV is a major respiratory pathogen as reported by cited articles with both RSV‐A and RSV‐B, circulating in Pakistan. It is responsible for causing the death of children and infants. Three genotypes of RSV‐B, BA‐9, BA‐10, and BA‐13, are observed. Influenza A (H1N1, H5N1, H3N2, and H1N1pdm09) and influenza B are common among Pakistani natives. Despite the fact that influenza strains keep circulating during the whole year but usually causes seasonal pandemics with high occurrence during winter and spring period. A number of diseases are associated with respiratory tract. However, available data include pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and influenza. Pneumonia is common among children whereas every year 2 to 3 episodes of influenza are commonly observed. Bronchiolitis is not common. On the other hand, such high mortality rate is also because of the inadequate awareness and lack of disease control strategies.

CONTRIBUTION

Z.F. conceived and designed the study. R.N., U.J., A.U., and S.A. collected the data and wrote the manuscript. Z.F. and A.G. finalized the draft and supervised the study. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

FUNDING

Higher Education Commission of Pakistan, Start‐Up Research Grant No. 1801.

Naz R, Gul A, Javed U, Urooj A, Amin S, Fatima Z. Etiology of acute viral respiratory infections common in Pakistan: A review. Rev Med Virol. 2019;29:e2024 10.1002/rmv.2024

REFERENCES

- 1. Simoes EAF, Cherian T, Chow J, Shahid‐Sallas SA, Ramanan L, John TJ. Acute respiratory infections in children In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al., eds. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. Chapter 25 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11786/. Co‐published by Oxford University Press, New York. 2nd ed. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2006. Accessed December 10, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zaidi AKM, Awasthi S, de Silva HJ. Burden of infectious diseases in South Asia. BMJ. 2004;328(7443):811‐815. 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. UNICEF . The state of the world's children 2017 statistical tables. https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/SOWC-2017-statistical-tables.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2017.

- 4. Population Reference Bureau . 2017. World Population Data Sheet. https://assets.prb.org/pdf17/2017_World_Population.pdf. Accessed December 8, 2017.

- 5. Khan TA, Madni SA, Zaidi AK. Acute respiratory infections in Pakistan: have we made any progress? J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14(7):440‐448. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15279753. Accessed December 10, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khalid S, Ghani E, Ayyub M. Study on etiology of viral lower respiratory tract infections in children under 10 years of age. J Virol Antivir Res. 2016;5(4). 10.4172/2324-8955.1000160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ali A, Akhund T, Warraich GJ, et al. Respiratory viruses associated with severe pneumonia in children under 2 years old in a rural community in Pakistan. J Med Virol. 2016;88(11):1882‐1890. 10.1002/jmv.24557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bashir U, Alam MM, Sadia H, Zaidi SSZ, Kazi BM. Molecular characterization of circulating respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) genotypes in Gilgit Baltistan Province of Pakistan during 2011‐2012 winter season. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74018 10.1371/journal.pone.0074018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bashir U, Nisar N, Arshad Y, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and influenza are the key viral pathogens in children <2 years hospitalized with bronchiolitis and pneumonia in Islamabad Pakistan. Arch Virol. 2017;162(3):763‐773. 10.1007/s00705-016-3146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ali A, Yousafzai MT, Waris R, et al. RSV associated hospitalizations in children in Karachi, Pakistan: implications for vaccine prevention strategies. J Med Virol. 2017;89(7):1151‐1157. 10.1002/jmv.24768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yousafzai MT, Ibrahim R, Thobani R, Aziz F, Ali A. Human metapneumovirus in hospitalized children less than five years of age in Pakistan. J Med Virol. 2018;90(6):1027‐1032. 10.1002/jmv.25044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Badar N, Aamir UB, Mehmood MR, et al. Influenza virus surveillance in Pakistan during 2008‐2011. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79959 10.1371/journal.pone.0079959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ghafoor A, Nomani NK, Ishaq Z, et al. Diagnoses of acute lower respiratory tract infections in children in Rawalpindi and Islamabad, Pakistan. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12(8):S907‐S914. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2270413. Accessed October 10, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization . Pneumonia. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs331/en/. Accessed December 8, 2017.

- 15. Ruuskanen O, Lahti E, Jennings LC, Murdoch DR. Viral pneumonia. Lancet. 2011;377(9773):1264‐1275. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bashir U, Nisar N, Mahmood N, Alam MM, Sadia H, Zaidi SS. Molecular detection and characterization of respiratory syncytial virus B genotypes circulating in Pakistani children. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;47:125‐131. 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tariq WU, Waqar T, Ali S, Ghani E. Winter peak of respiratory syncytial virus in Islamabad. Trop Doct. 2005;35(1):28‐29. 10.1258/0049475053001958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ali SA, Aziz F, Akhtar N, Qureshi S, Edwards K, Zaidi A. Pandemic influenza A(H1N1)pdm09: an unrecognized cause of mortality in children in Pakistan. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45(10):791‐795. 10.3109/00365548.2013.803292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ali A, Khowaja AR, Bashir MZ, Aziz F, Mustafa S, Zaidi A. Role of human Metapneumovirus, Influenza A virus and respiratory syncytial virus in causing WHO‐defined severe pneumonia in children in a developing country. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74756 10.1371/journal.pone.0074756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khan MY, Iqbal Z, Khan J, Amin M. Clinico‐radiological profile, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)‐ positivity and outcome ‐ analysis in hospitalized suspected H1N1 pneumonia; efficiency assessment of health care delivery system. A pilot study. Pakistan Journal of Chest Medicine. 2016;22(3):92‐101. http://pjcm.net/index.php/pjcm/article/viewFile/406/350. Accessed December 12, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bourke T, Shields M. Bronchiolitis. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011;2011:0308 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3275170/. Accessed December 12, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amber R, Adnan M, Tariq A, Mussarat S. A review on antiviral activity of the Himalayan medicinal plants traditionally used to treat bronchitis and related symptoms. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;69(2):109‐122. 10.1111/jphp.12669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization . Influenza (Seasonal). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/. Accessed December 10, 2017.

- 24. Javed F, Manzoor KN, Ali M, et al. Zika virus: what we need to know? J Basic Microbiol. 2018;58(1):3‐16. 10.1002/jobm.201700398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization . Human infection with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus: updated interim WHO guidance on global surveillance. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/guidance/surveillance/WHO_case_definition_swine_flu_2009_04_29.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 26. Nair H, Brooks WA, Katz M, et al. Global burden of respiratory infections due to seasonal influenza in young children: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9807):1917‐1930. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61051-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization . Weekly epidemiological record. 2008; 83(40): 356‐364. http://www.who.int/wer/2008/wer8340.pdf?ua=1. Accessed October 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zaman M, Ashraf S, Dreyer NA, Toovey S. Human infection with avian influenza virus, Pakistan, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis 2011. 2011, June;17(6):1056‐1059. 10.3201/eid1706.091652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aamir UB, Badar N, Mehmood MR, et al. Molecular epidemiology of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses from Pakistan in 2009–2010. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e41866 10.1371/journal.pone.0041866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ijaz M, Khan MJ, Khan J, Usama U. Association of clinical characteristics of patients presenting with influenza like illness or severe acute respiratory illness with development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2017;87(1):18‐21. 10.4081/monaldi.2017.765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]