Short abstract

Objectives

The study aim was to determine the effect of an occupational blood-borne pathogen exposure (OBE) management program based on the PRECEDE-PROCEED model on knowledge, attitude and behaviour regarding OBE prevention among operating room nurses.

Methods

This was a one-group pre-test post-test experimental study. The PRECEDE-PROCEED model was used to design and evaluate the effect of an OBE management program on 87 operating room nurses from February to July 2018. The study included pre-intervention assessment; risk factor analysis; interventions targeted to predisposing, reinforcing and enabling factors and focusing on areas of low scoring; and a post-intervention assessment. Attitudes, knowledge and behaviour compliance regarding OBE were measured before and after the 6-month program using a self-developed questionnaire. Descriptive epidemiological analysis and t-tests were used for data analysis.

Results

Low-scoring items for OBE knowledge, attitudes and behaviour were identified in the baseline assessment. Six months post-intervention, there were significant improvements in attitudes toward OBE prevention, in knowledge about OBE safety precautions and in behaviour compliance with standard precautions.

Conclusions

The findings indicate the effectiveness of an OBE management program based on the PRECEDE-PROCEED model for improving knowledge, attitudes and behaviour adherence to OBE prevention among operating room nurses.

Keywords: Operating room nurse, occupational exposure, PRECEDE-PROCEED model, blood-borne pathogen, China, descriptive epidemiological analysis

Introduction

Occupational blood-borne pathogen exposure (OBE) refers to injuries sustained by health care workers, who can be infected with blood-borne pathogens through blood and body fluid exposure (BBFE), needle-stick injuries or sharp instruments.1 Operating room nurses experience a substantial risk of OBE from BBFE, needle-stick injuries and sharp instruments owing to the nature of their work.2 Accidents may result from low levels of knowledge, lack of adherence to all precautions, and a lack of availability of equipment necessary to prevent OBE.3 Our previous survey in 2013 to 2015 showed that 80.80% of operating room nurses had OBE experiences within this period, and 54.30% were younger than 30 years old.4 Young nurses may be at high risk of OBE owing to lack of experience and practice of preventive measures. OBE experiences have physical and psychological effects on operating room nurses; one study showed that 57.00% of nurses believe that the risk of infection cannot be avoided in the operating room and only 32.70% of nurses reported to the hospital infection control department after an OBE accident.5 Therefore, effective training in post-exposure management should be provided to increase knowledge and concerns about OBE, change negative attitudes and improve poor preventive behaviour to reduce the consequences of OBE.

Project management is the application of knowledge, skills and tools to project activities to meet the needs and expectations of project stakeholders.6 Baoji Municipal Central Hospital has introduced project management theory into the practice of occupational health protection management of health care workers.7,8 Management programs may be useful in preventing the risk of OBE among operating room nurses. It is important to select a target and appropriate model that best suit the program before conducting any theory-based intervention plan.9 PRECEDE-PROCEED is a comprehensive model for planning, implementing and evaluating health promotion or disease prevention programs designed by American health educators Green and Kreuter.10 In the context of educational diagnosis and evaluation, PRECEDE stands for predisposing, reinforcing and enabling constructs; PROCEED stands for regulatory, policy and organizational constructs.11 The predisposing factors in the current study were knowledge, attitudes and self-preventive behaviour toward standard OBE precautions. Enabling factors were the available infrastructure, resources and skills. Reinforcing factors were the attitudes of individuals (hospital leader, head nurse, peers) who influence the adoption of safety actions.12

The PRECEDE-PROCEED model was used as a guide to plan and implement an OBE intervention program in the operating room of Baoji Municipal Central Hospital from February to July 2018. The study aims were to implement an OBE management program based on the PRECEDE-PROCEED model, and to investigate the following issues: 1) the levels of knowledge, attitudes and preventive behaviour before the intervention and after 6 months of the program intervention, 2) whether the OBE program increased safety knowledge, changed negative attitudes and enhanced behavioural adherence to standard prevention practice among participants.

Method

Design and participants

We designed the workflow of the OBE management program, and set up a leading program team comprising members of four hospital departments (the director and head nurse for the operating room, the director of the nursing department, the director of the infection control department and the director of the purchasing agency). The team groups assumed corresponding responsibilities and provided human and financial support.

This semi-experimental study was conducted in the operating room of a tertiary general hospital, Baoji Municipal Central Hospital, which has a capacity of 1600 beds. Eighty-seven operating room nurses were selected as participants using cluster sampling. The inclusion criteria were (1) registered nurses assisting in surgery; (2) at least 1 year of operating room work experience; (3) willingness to participate in the survey. The exclusion criteria were (1) intern nurses and trainee nurses; (2) operating room nurses who did not undertake work that involved OBE risk, such as head nurses; (3) no desire to participate. All participants were informed about the study purpose and protocol and provided their oral consent. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Baoji Municipal Central Hospital (IRB No. BZYL-2017-12-1).

The study used a pre-test post-test assessment of a program delivered from February to July 2018 based on the first seven phases of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model. Phases 1 to 5 were related to the PRECEDE stage and phases 6 to 7 related to the PROCEED stage. The final outcomes of the program (following phases 8 and 9) were not assessed in this study. The assessments were as follows:

Phase 1: This involved a social assessment of operating room nurses based on our previous 2013 to 2015 survey of OBE epidemiological characteristics.

Phase 2: Epidemiological assessment of OBE prevalence among operating room nurses was conducted. In addition, an environmental assessment was carried out of current available equipment for OBE prevention, workflow and work hours in the operating room. This assessment comprised a brainstorm by all the staff in the study group.

Phase 3: This phase assessed operating room nurses’ attitudes, knowledge and preventive behaviour regarding standard OBE precautions.

Phase 4: In this phase, the predisposing, enabling and reinforcing factors were identified and categorized and a plan for the educational intervention was developed.

Phase 5: The existing administrative OBE preventive policy, training mode and OBE reporting system were assessed.

Phase 6: An intervention plan was developed and intervention measures were implemented.

Phase 7: At the end of the 6-month program, the knowledge, attitudes and preventive behaviour adherence regarding OBE were evaluated.

Assessment measures

Three type of assessment were conducted. Sociodemographic factors were measured using a questionnaire that assessed OBE among operating room personnel. This questionnaire has previously shown good reliability and Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.810 and 0.732.4,5 This measure assesses demographic characteristics (including sex, age, education level, operating work experience, professional status, hepatitis B surface antibody status and amount of training for OBE prevention) and OBE history (time of exposure, number of occurrences, exposure level, site and source of exposure).

Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour regarding OBE prevention and protection were assessed using an anonymous questionnaire based on the ‘National Occupational Exposure to Blood-borne Pathogens Prevention guide’13 and the ‘National Occupational Exposure Protection to HIV guide’.14 The content validity index of this questionnaire is 0.890 and Cronbach’s alpha 0.726.15 A preliminary test was conducted before the formal investigation with 30 nurses working on the general surgery wards of the same hospital. The validity was tested by four experienced professors by assessing the questionnaire content, comprehensiveness and time taken to complete the measure. The questionnaire consisted of three parts that assessed attitudes, knowledge and preventive behaviour adherence regarding OBE. Nurses’ knowledge of OBE was assessed using 14 questions. A correct response was assigned 1 point and an incorrect response assigned 0 points; higher scores indicated better OBE knowledge. Attitudes toward OBE were assessed using 10 questions. Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale: completely disagree (1), disagree (2), not sure (3), agree (4) and completely agree (5). The total possible score was 50; higher scores indicated positive attitudes toward OBE prevention. Behaviour was assessed using 16 single-choice questions on a 4-point Likert scale: never (0), sometimes (1), often (2) and always (3). The total possible score was 0 to 48 points; higher scores indicated proper protective behaviour.

The operating room environment was assessed using a previously developed measure based on relevant literature. This involved a physical and physiological OBE prevention assessment of the operating room (Cronbach’s alpha for this measure is 0.91).16 Nine criteria were used to assess the operating room environment: fatigue from long working hours, inadequate number of nurses, noise in the workplace, inadequate workspace, protective equipment available, presence of regulations and policy regarding standard precautions, adequate hand-washing, good relationship between nurses and surgeon or nurses and nurses, and preventive and protective culture in the operating room.

Intervention methods

After the PRECEDE phases, the OBE prevention program was implemented using three interventions to address the following three factors: targeted OBE health education, improving the management policy and protective equipment to facilitate behaviour change, and standard precaution monitoring. The first intervention delivered health education targeted to the predisposing factors. Three sessions of health education teaching were conducted from Monday through Friday over 3 weeks. A total of 18 to 20 of the 87 participants attended the sessions and received training materials each day, according to their availability. The educational contents included specific topics identified in the PRECEDE phases (Table 1).

Table 1.

OBE management program intervention plan for predisposing factors among operating room nurses (mean scores).

| Session | Items | Intervention items | Resource | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st session | Knowledge | Definition and categories; knowledge of OBE prevention; policies, laws and regulations regarding OBE occupational prevention and control; risk factors, route and protective measures for OBE by sharp instrument injury and blood or body fluid splash; appropriate post-exposure practices and reporting system. Proper handling procedures for medical waste and use of sharps containers | Multimedia PowerPoint (PPT) teaching, video, booklets, motivational testing, case discussions, field operations | 3 hours |

| 2nd session | Attitudes | Danger of blood-borne infectious disease during work practice; perceived severity of disease; perceived behavioural problems; the need to improve self-efficacy | Multimedia PPT teaching, video | 2 hours |

| 3rd session | Behaviour | Standard precautions including seven-step hand-washing skills; proper wearing and taking off of non-sterile gloves, masks, goggles and protective suit. Emergency procedure in the event of OBE and procedure for completing the report form. Appropriate procedure for handling used sharp instruments and injection equipment disposal | Multimedia PPT teaching, video and case discussions, field practice | 3 hours |

OBE: occupational blood-borne pathogen exposure.

The second intervention focused on improving the management policy and protective equipment to facilitate behaviour change targeted to the enabling factors. This component was implemented for 2 months. The contents of the intervention were designed to improve the management system and occupational operation procedure, change unsafe operation policies and purchase necessary protective equipment. The intervention focused on the following strategies: 1) The establishment of a neutral instrument zone. This involved identifying a fixed zone on the instrument tray for sharp instruments (surgical scalpel, needle and local anaesthetic injection needle) to enable a hands-free technique. This helps to reduce the rate of sharp device injuries by preventing two surgical team members touching the same sharp item simultaneously or passing and receiving surgical instruments.17 2) Strict implementation of the following regulations: classify and safely discard all devices during the operation procedure and after surgery; the box for discarding sharps should not exceed two-thirds of the whole container; surgical blades should be gripped using forceps or a needle holder to avoid accidental injury; an injection needle with safety protection should be used during local anaesthesia practice, and two-hand recapping is prohibited. 3) Improvement of self-protective equipment, such as wearing double-use gloves and a one-piece mask with eye protection or face shield, the reduction of the use of sharp instruments or needles, and supporting the use of sharps with safety protection devices.

The third intervention was a standard precaution monitoring targeted to the reinforcing factors. This component was similar to that of the first intervention and involved setting up a supervision system and information platform, a WeChat group and a QQ group, (WeChat and QQ are chat apps) with a key focus on developing standard compliance precautions. Reminder text messages about risk factors were sent to the information platform to further strengthen knowledge related to the importance of protective measures and adherence to standard prevention measures, the impact of exposure, post-exposure practice and reporting procedures. Videos were sent to the platform about how to correctly wear and take off gloves and goggles, apply standard hand-washing skills, and correct handling of an OBE (i.e. rinse well with water and apply antiseptic). The head nurse of the program provided continuous supervision, organized a free hepatitis B vaccination, and established a blood-based occupational exposure monitoring report system sheet and health record for nurses in the operating room. Feedback and supervision inspection were conducted every month to remind participants of the program.

Data collection procedure

Each investigator provided a standard explanation of the purpose and significance of the survey to participants. The questionnaire was administered on site by trained investigators of the study group and questionnaires were completed anonymously. (1) Baseline survey: After obtaining consent from participants, questionnaire data on demographics and baseline information about attitudes, knowledge and behaviour regarding OBE were obtained. Eighty-seven distributed questionnaires were collected before the intervention (February 2018), a response rate of 100% (87/87). (2) Survey of intervention effect at the end of 6 months: 87 questionnaires were distributed after the intervention (October 2018); the response rate was 98.85% (86/87).

Data analysis

Data from eligible pre-intervention and post-intervention questionnaires were entered into EpiData 3.0 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark). Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 22.0 (Chinese Version) (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA). Data for OBE knowledge, attitudes and preventive behaviour were presented using means and standard deviations (). The difference in pre-intervention and post-intervention scores was examined using t-tests. Frequency data were presented using frequencies or ratios (%) and analysed descriptively. Probability values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 94.26% of participants were female and the mean age was 32.32 ± 5.58 years. The mean years of experience as an operating room nurse was 11.97 ± 1.99 years; 74.71% (68/87) of participants had experienced an OBE accident in the last year. Of these, 23.53% (16/68) had had two OBE accidents and 7.35% (5/68) had had three OBE accidents. The OBE exposure rate after 1 to 5 years, 6 to 10 years, 11 to 15 years and ≥16 years of operating room work experience was 36.76%, 26.47%, 13.24% and 20.59%, respectively. The most common injury sites were the front of the hand (33.88%) and the back of the hand (26.83%). Percutaneous exposure was the most common accident (64.50%), followed by skin exposure (intact skin 13.75%, non-intact skin 7.05%). A total of 51.77% of nurses reported to the OBE management unit after exposure. Of participants, 91.95% worked continuously for 6 to 10 hours during a shift. A total of 78.17% were not sure about their present hepatitis B status and 80.46% could not remember when they had last had a hepatitis B vaccination.

Baseline evaluation

The total possible OBE knowledge score was 9 points; the mean baseline score was 4.76 ± 1.37. Table 2 shows the three items with the highest number of correct responses and the three items with the lowest number of correct responses. The total possible OBE attitude score was 50 points; the baseline score was 28.20 ± 4.53. Table 3 shows the three items with the highest number of positive scores and those with the lowest number of positive scores. The total possible OBE preventive behaviour score was 48 points; the baseline score was 30.59 ± 1.23. The baseline results showed that 43.68% of nurses thought that only the blood and body fluids of patients with infections constituted an infection risk, 63.22% of nurses believed that wearing a protective suit, goggles and double-use gloves was inconvenient and 64.37% thought that sharp instrument injury and blood or body fluid spattering were not preventable in routine work practice. Table 4 shows the three items with the highest number of correct responses and those with the lowest number of correct responses.

Table 2.

OBE prevention knowledge among operating nurses in baseline survey: items with the most correct and incorrect responses (n = 87).

| Items | Correct responses(n) | Rate of correct responses (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Three items with the highest correct response rate | ||

| All used needles should be discarded into a safe container after separation with a syringe | 85 | 97.70 |

| Standard precautions for using disposable gloves during routine patient treatment | 82 | 94.25 |

| The handling procedure for waste produced by patients with confirmed or suspected blood-borne infections is the same as that of patients with non-infectious pathogens | 81 | 93.10 |

| Three items with the lowest correct response rate | ||

| Reporting requirements and procedures after exposure | 53 | 60.92 |

| Serologic testing and emergency practice after sharps injury | 35 | 40.23 |

| Knowledge about treatment in the event of exposure to HIV, hepatitis B or AIDS pathogens | 33 | 37.93 |

OBE: occupational blood-borne pathogen exposure.

Table 3.

Attitudes toward OBE prevention among operating nurses in baseline survey: items with the highest and lowest positive scores (n = 87).

| Items | No. of positive responses (n) | Rate of positive responses (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Three items with the highest positive score | ||

| A good medical environment (protective equipment, convenient sharps container) is effective in reducing the occurrence of OBE | 81 | 93.10 |

| It is necessary to establish a sound occupational exposure system for nurses | 80 | 91.95 |

| It is essential to follow standard treatment for wounds after exposure | 78 | 89.65 |

| Three items with the lowest positive score | ||

| Blood and body fluids are infectious regardless of the patient’s infection status | 49 | 56.32 |

| Wearing a protective suit, goggles and double-use gloves is inconvenient | 32 | 36.78 |

| Sharp instrument injuries and blood or body fluid spattering are preventable in routine work practice | 31 | 35.63 |

OBE: occupational blood-borne pathogen exposure.

Table 4.

Preventive behaviour among operating room nurses: items with the highest and lowest number of correct responses (n = 87).

| Items | No. of correct responses (n) | Rate of correct responses (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Three items with the highest correct score | ||

| Place scarp and suture needles into the sharps container after use | 87 | 100 |

| Classify management of medical waste and domestic waste | 85 | 97.70 |

| Wear gloves and mask when contacting patients with confirmed infectious disease | 80 | 91.95 |

| Three items with the lowest correct score | ||

| Squeeze and clean the area followed by hand disinfection with hydroalcoholic solution; fill in the report form after any OBE occurrence | 37 | 42.53 |

| Check whether used gloves are intact after treating patients | 24 | 27.59 |

| Wear gloves when giving intravenous or subcutaneous injections | 19 | 21.84 |

OBE: occupational blood-borne pathogen exposure.

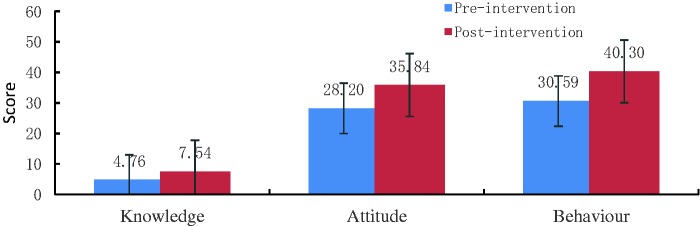

Post-intervention knowledge, attitudes and behaviour scores

The average scores for knowledge, attitudes and behaviour after the intervention were higher than those before the intervention, and these differences were significant (t = 15.44, 12.95 and 53.94, respectively; P < 0.05). (Table 5) (Figure 1).

Table 5.

Comparison of knowledge, attitudes and behaviour data pre- and post-intervention.

| Groups | Knowledge | Attitudes | Behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention (n = 87) | 4.76 ± 1.37 | 28.20 ± 4.53 | 30.59 ± 1.23 |

| Post-intervention (n = 86) | 7.54 ± 0.97 | 35.84 ± 3.10 | 40.30 ± 1.15 |

| t | 15.44 | 12.95 | 53.94 |

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Figure 1.

Comparison of OBE knowledge, attitudes and behaviour scores among operating room nurses. Bars indicate the mean scores.

Discussion

The study aim was to conduct an OBE management program based on the PRECEDE-PROCEED model. The results showed that this 6-month program significantly improved OBE knowledge, attitudes and behaviour adherence of operating room nurses.

Program management could encourage health care workers to undertake training and help to improve their knowledge.18 The PRECEDE phases of the program indicated that operating room nurses did not have sufficient knowledge about serologic testing and emergency procedures after sharps injury, reporting requirements and post-exposure procedure, and particularly lacked knowledge of treatment in the event of exposure to HIV, hepatitis B and AIDS pathogens. These findings are consistent with those of a study by Butsashvili et al.,19 which showed that operating room nurses did not have a high level of knowledge about OBE. El Beltagy et al.20 have suggested that education has a positive impact on behaviour by resolving misunderstandings and filling knowledge gaps. In this study, we clarified existing misconceptions about blood-borne pathogens and post-exposure treatment regimens, and increased knowledge about OBE using lectures, motivational case discussions, booklets and reminder text messages. After the 6-month OBE management program, mean knowledge scores significantly increased from baseline scores. A similar pattern was found in a study by Li et al.,21 in which medical staff who received a tailor-made education course showed the highest improvement in OBE knowledge.

Our baseline results for OBE prevention attitudes showed that 43.68% of nurses thought that only the blood and body fluids of patients with infections constituted an infection risk. Almost two-thirds of nurses thought that wearing a protective suit, goggles and double-use gloves was inconvenient and that sharp instrument injury and blood or body fluid spattering were not preventable in routine work practice. After the invention, attitudes toward OBE protection significantly improved (the mean score increased from 28.20 ±4.53 to 35.84 ± 3.10). This improvement may be attributable to continuous and dynamic tailor-made supervision, regular health check-ups, free hepatitis B vaccination, and the post-exposure follow-up and monitoring system. These measures helped nurses to understand that OBE is preventable and controllable.22 Nurses could proactively attend the educational training, which helped them to understand the importance of standard precautions, and encouraged them to take safety precautions regardless of the suspected or confirmed infection status of patients.

Compliance with standard precautions is a core issue in OBE management.23 Individual factors, organizational climate and environmental constraints play a major role in behavioural intentions regarding hygiene precautions.3 Our baseline results showed that the lowest preventive behaviour scores were for wearing gloves while giving intravenous or subcutaneous injections. This may be because the use of gloves when giving injections is not recommended in the textbook ‘Basic Nursing’ used by nurses in China. Almost three-quarters of nurses did not tend to check whether used gloves were intact. The present study translated knowledge about these issues into preventive behaviour using motivational training and interactive practice. Such interventions may help health care workers pay more attention to post-exposure practice and prophylaxis, biomedical waste management procedures and skills related to the wearing and taking off of protective clothing. A study by Sezgin and Esin showed that a medical staff management program using a model-based approach improved occupational health protection.24 The 6-month program in the present study significantly improved preventive behaviour scores, consistent with Green’s health education intervention model.24

One strength of this study is that this is the first study to use the PRECEDE-PROCEED model as a framework to improve OBE knowledge, attitudes and preventive behaviour in operating room nurses. This integrated and individualized program clarified nurses’ understanding and corrected their misunderstandings about OBE, translating information into preventive behaviour in routine practice. However, there were some study limitations. First, only the first seven phases of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model were followed; the sustainability of the changes and the final outcome following phases 8 and 9 were not evaluated to determine whether OBE accidents reduced as a result of improvements in attitudes, knowledge and behaviour. Second, the study was conducted in only one hospital, so the findings may not be completely representative of operating room nurses in other hospitals. In addition, this was a pre-test post-test study rather than a controlled experimental study, so the findings may have overestimated or underestimated the changes.

Conclusions

This study used the PRECEDE-PROCEED model to develop a tailor-made OBE management program to assess several interlinked factors that may affect knowledge, attitudes and preventive behaviour. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use such a program to address the needs of operating room nurses regarding OBE. It was found that the 6-month program significantly improved OBE knowledge, attitudes and preventive behaviour. This program may be an effective approach to improving knowledge, attitudes and adherence in other clinical settings.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to all the nurses who participated in the training and investigation. We thank Xiaoyan Wang, Xiaohui Luo and Zhen Qin for their contributions to the training and study design.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD

References

- 1.Mannocci A, De Carli G, Di Bari V, et al. How much do needlestick injuries cost? A systematic review of the economic evaluations of needlestick and sharps injuries among healthcare personnel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016; 37: 635–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasatpibal N, Whitney JD, Katechanok S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of needlestick injuries, sharps injuries, and blood and body fluid exposures among operating room nurses in Thailand. Am J Infect Control 2016; 44: 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fathi Y, Barati M, Zandiyeh M, et al. Prediction of preventive behaviors of the needlestick injuries during surgery among operating room personnel: application of the health belief model. Int J Occup Environ Med 2017; 8: 232–240. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2017.1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin H, Yu L, Wang X. . The study on risk factors and preventive measures of sharp injury in operating room. China Comprehensive Clinical 2015; 12: 4016–4019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin H, Yu L, Wang X. . Correlation between blood borne occupational exposure and mental health of operating room nurses in three hospitals. Chinese Journal of Nursing Research 2014; 28: 4016–4019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan WR. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide). PA, USA: Project Management Institute, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hua L, Wang CJ. . Study of quality control circle in reducing preparation defect rate of endoscopic surgical instruments. Clinical Research and Practice 2017; 5: 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chacón Moscoso S, Sanduvete Chaves S, Portell Vidal M, et al. Reporting a program evaluation: Needs, program plan, intervention, and decisions. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 2013; 13: 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azar FE, Solhi M, Darabi F, et al. Effect of educational intervention based on PRECEDE-PROCEED model combined with self-management theory on self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2018; 12: 1075–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zoungrana J, Yaméogo TM, Kyelem CG, et al. Blood exposure accidents: knowledge, attitudes and practices of nursing and midwifery students at the Bobo-Dioulasso teaching hospital (Burkina Faso). Med Sante Trop 2014; 24: 258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green LW, Kruter MW, Deds SQ, et al. Health education planning: a diagnostic approach. Mountain View CA: Mayfield, 1980, pp.2–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green LW, Kruter MW. Health promotion planning: an educational and environmental approach. 2nd ed Mountain View CA: Mayfield, 1991. 10.1016/0738-3991(92)90152-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health. National occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens prevention guide (GBZ / T 213-2008). Beijing, China: Ministry of Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health. National occupational exposure protection to HIV guide. Beijing, China: Ministry of Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cutter J, Jordan S. . Inter-professional differences in compliance with standard precautions in operating theatres: a multi-site, mixed methods study. Int J Nurs Stud 2012; 49: 953–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan MF, Ho A, Day MC. Investigating the knowledge, attitudes and practice patterns of operating room staff towards standard and transmission-based precautions: results of a cluster analysis. J Clin Nurs 2008; 17: 1051–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong IS, Park S. Use of hands-free technique among operating room nurses in the Republic of Korea. Am J Infect Control 2009; 37: 131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giard M, Laprugne-Garcia E, Caillat-Vallet E, et al. Compliance with standard precautions: results of a French national audit. Am J Infect Control 2016; 44: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butsashvili M, Kamkamidze G, Kajaia M, et al. Occupational exposure to body fluids among health care workers in Georgia. Occup Med (Lond) 2012; 62: 620–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Beltagy K, El-Saed A, Sallah M, et al. Impact of infection control educational activities on rates and frequencies of percutaneous injuries (PIs) at a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health 2012; 5: 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, Zhang Q, Weng S, et al. Application of the new management mode “Knowledge, attitude, practice, quality control, revise” in the prevention of bloodborne occupational exposure of medical staff. Chinese Journal of Health Education 2019; 5: 474–476. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Y, Qi S, Guo L, et al . Application effects research on Precede-Proceed Health Education model in occupational protection intervention among undergraduate nursing students. Nurs Res 2017; 34: 4434–4437. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michinov E, Buffet-Bataillon S, Chudy C, et al . Sociocognitive determinants of self-reported compliance with standard precautions: development and preliminary testing of a questionnaire with French health care workers. Am J Infect Control 2016; 44: 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sezgin D, Esin MN. Effects of a PRECEDE-PROCEED model based ergonomic risk management programme to reduce musculoskeletal symptoms of ICU nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2018; 47: 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]