Abstract

Aims:

The complexity of Interstitial Cystitis/bladder Pain Syndrome (IC/BPS) has led to a great deal of uncertainty around the diagnosis and prevalence of the condition. Under the hypothesis that IC/BPS is frequently misdiagnosed, we sought to assess the accuracy of the ICD-9/ICD-10 code for IC/BPS using a national data set.

Methods:

Using the Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure, we identified a random sample of 100 patients with an ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnosis of IC/BPS (595.1/N30.10) by querying all living patients in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system. We purposely sampled men and women equally to better understand gender-specific practice patterns. Patients were considered a correct IC/BPS diagnosis if they had two visits complaining of bladder-centric pain in the absence of positive urine culture at least 6 weeks apart. Patients were considered not to have IC/BPS if they had a history of pelvic radiation, systemic chemotherapy, metastatic cancer, or bladder cancer.

Results:

Of the 100 patients, 48 were female and 52 were male. Five had prior radiation, one had active cancer, and 10 had bladder cancer (all male), and an additional fifteen had insufficient records. Of the remaining 69 patients, 43% did not have IC/BPS. Of these patients who did not have IC/BPS, 43% complained only of overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms, which was more common in women (63%) than men (21%), P = .003.

Conclusions:

In our small sample from a nationwide VA system, results indicate that IC/BPS has a high misdiagnosis rate. These findings shed light on the gender-specific diagnostic complexity of IC/BPS.

Keywords: claims data, diagnosis, epidemiology, painful bladder, Veterans Affairs

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Estimates of the prevalence of Interstitial Cystitis/bladder Pain Syndrome (IC/BPS) fluctuate widely. The prevalence of IC/BPS for women in the literature has ranged from as low as 0.045% in administrative claims data to 6.5% in a population-based telephone study.1,2 In men the prevalence is lower, from 0.008% in administrative claims analyses to4.2% in a population-based telephone study.3–7 Such a lack of accuracy in estimating the national prevalence is a major limitation to further research in the field. This uncertainty is due to several factors but the lack of a diagnostic standard for IC/BPS is by far one of the greatest.8

According to the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine, and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU), IC/BPS is defined as “an unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, and discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than 6 weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes.”9–12 While there are several diagnostic tests used for IC/BPS including urinalysis, urine culture, potassium sensitivity testing, cystoscopy, and biopsy of the bladder, none of these tests can definitively diagnose IC/BPS.3 Because there are no specific diagnostic criteria for IC/BPS, the diagnosis is most often made only after other conditions have been excluded.

The first diagnostic criteria for IC/BPS were published by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) in 1988 and were intended for use in research.13 These criteria included the presence of glomerulations or Hunner’s lesions in addition to bladder pain or urinary urgency. Patients were excluded from having IC if they had, among other factors, a normal capacity bladder, a lack of nocturia, or a response to anticholinergics. However, past research revealed that when the NIDDK criteria are applied, more than 60% of IC/BPS cases may be missed.14 There continues to be a great deal of uncertainty and inconsistency in the diagnosis of IC/BPS. While pain related to the bladder is the hallmark symptom of IC/BPS, there is no single definition of IC/BPS that can both identify all IC/BPS cases and distinguish these cases from similar conditions, such as overactive bladder (OAB), endometriosis, and vulvodynia.15

The purpose of this study was to assess the accuracy of the International Classification of Disease, both 9th and 10th Edition (ICD-9/ICD-10) diagnosis code for IC/BPS. We identified a sample of patients nationwide receiving care through the Veterans Health Administration with an ICD-9 and ICD-10 code for IC/BPS (595.1/N30.10). We conducted an extensive chart review on these patients to independently verify whether the patients met clinical criteria that confirmed the diagnosis of IC/BPS. We hypothesized that the accuracy of ICD codes for IC/BPS would vary between genders and that there would be a high frequency of misdiagnosis of IC/BPS.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining IRB approval (number: Pro00041326), the Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) was used to identify all patients suspected of having IC/BPS in the VA system between 1999 and 2016 by querying ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis of IC/BPS (595.1/N30.10). Of 164 845 patients suspected to have IC/BPS, we selected a sample of 1200 patients for a larger prevalence study. For this analysis, we selected the first 50 men and 50 women on which to perform a detailed chart review to assess the accuracy of the IC/BPS diagnosis. We purposely oversampled men to compare practice patterns between men and women with IC/BPS and later study risk factors. Chart review was performed by trained personnel. Clinical Research Associates (CRAs) performed detailed chart abstraction. CRAs were trained by a urologist and a supervisor responsible for coordinating the project. CRAs followed a detailed data abstraction standard operating procedure (SOP) that was developed by project leaders. When the diagnosis was in doubt, a final decision was made by a urologist who specializes in managing IC/BPS. When complicated cases arose that were not covered by the abstraction SOP, patients were reviewed by a urologist in biweekly review sessions with CRA’s and the data abstraction SOP was updated to ensure data was abstracted consistently moving forward.

Given the heterogeneous nature of IC/BPS we developed three criteria that would constitute a correct diagnosis of IC/BPS. Patients who were a correct IC/BPS diagnosis met at least one of the following criteria:

Two visits (in the VA system) complaining of unpleasant bladder centric sensation in the absence of positive urine culture at least 6 weeks apart

One visit complaining of bladder centric pain/unpleasant bladder centric sensation and a second visit complaining of “likely” IC/BPS-related pain in the absence of positive urine culture at least 6 weeks apart (both at the VA). We defined “likely” IC/BPS-related pain as pain that could be due to IC/BPS but without a specific complaint of bladder-centric pain or bladder tenderness on exam. Symptoms of “likely” IC/BPS include dysuria, pelvic pain, chronic lower abdominal pain, dyspareunia.

A history of bladder pain and/or a history of IC/BPS (in the VA or other system) with one additional visit complaining of bladder centric pain in the absence of a positive urine culture.

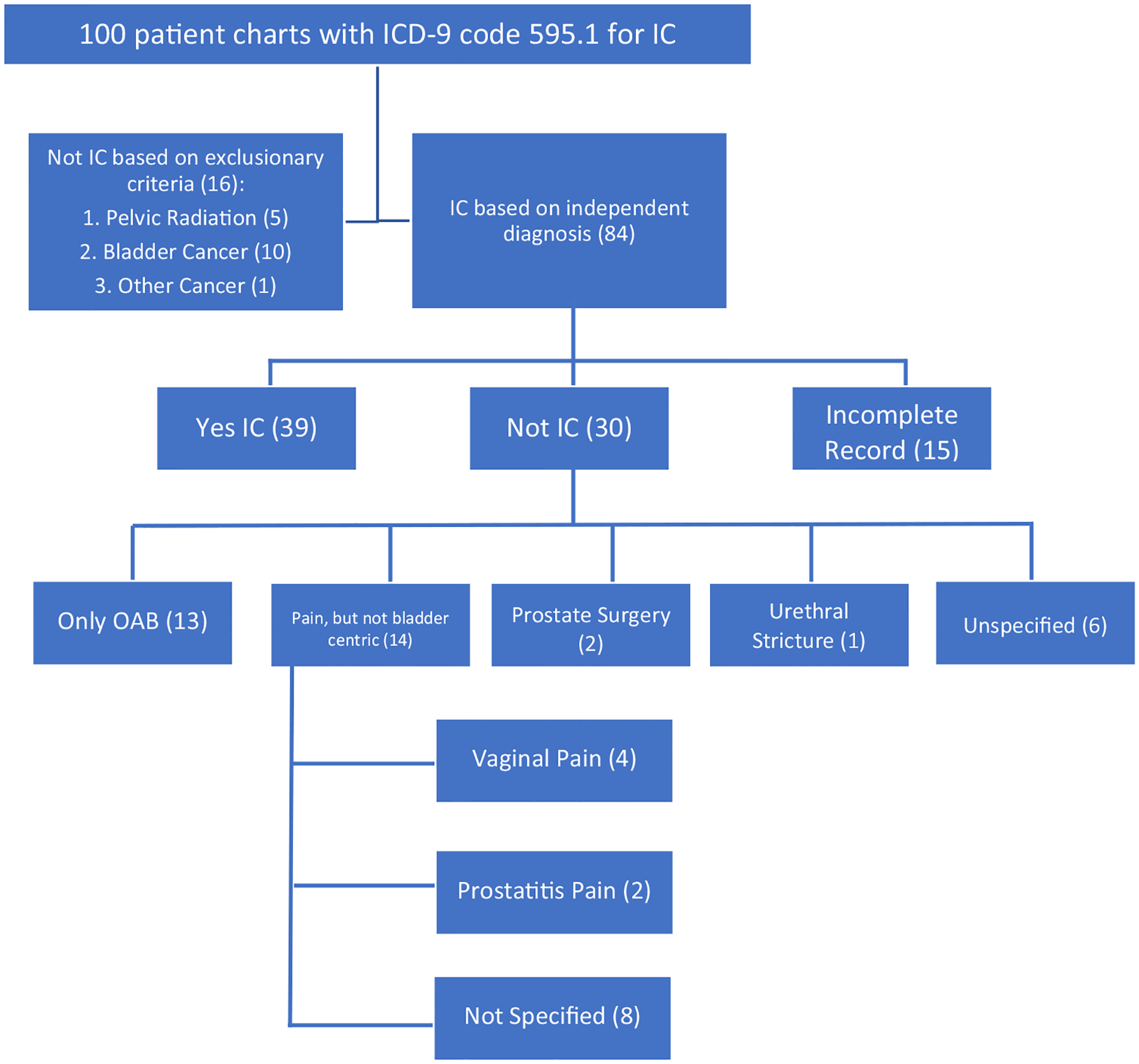

If the patient did not meet the above criteria for an IC/BPS diagnosis, we considered them a misdiagnosis of IC/BPS and the characteristics of these patients such as location of pain other than bladder were recorded. Patients were also considered a misdiagnosis of IC/BPS if they had a history of any of the following exclusionary criteria: pelvic radiation or systemic chemotherapy before IC/BPS diagnosis, bladder cancer at any time point, metastatic cancer before IC/BPS diagnosis, prior cystectomy, or if they were actively undergoing cancer treatment at the time of IC/BPS diagnosis. If there was insufficient information in a patient’s record to confirm IC/BPS diagnosis, they were classified as equivocal. The breakdown of patient groups is summarized in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Breakdown of Interstitial Cystitis/bladder Pain Syndrome patients reviewed

Demographic and disease characteristics were summarized using median (interquartile range) for continuous variables (because they followed nonnormal distributions) and count and percentage for categorical variables. Characteristics were summarized among all 100 patients. Differences in patient characteristics were tested using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Demographic characteristics included age, gender, race, and ethnicity. Disease characteristics included year of diagnosis, specific pain location, presence of active urethral stricture disease, and the presence of urinary frequency, urgency, and urge urinary incontinence (OAB symptoms). Symptoms among patients misdiagnosed with IC/BPS were compared between races using Fisher’s exact test.

3 |. RESULTS

Of the 100 patients reviewed, 48 were female and 52 were male (Table 1). Median (interquartile range) age at IC/BPS diagnosis by an ICD-9/ICD-10 code was 54 (range 39–68) and median (IQR) year of diagnosis code was 2010 (range 2005–2014). The racial distribution of patients was 20% black, 75% white, 2% Asian/Pacific Islander, 1% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 2% unknown. Overall, 6% of patients were of Hispanic ethnicity. Sixteen were considered a misdiagnosis due to exclusionary criteria, all of whom were male. Of these 16 patients, five received pelvic radiation, 10 had a history of bladder cancer, and one had active nonurologic cancer (Table 1). In addition, 15 patients were classified as equivocal by chart review as they did not have adequate data to confirm or refute a diagnosis of IC/BPS and therefore were excluded.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of all patients reviewed

| Total (N = 100) | |

|---|---|

| Age at VA IC diagnosis | |

| Median (IQR) | 54 (39, 69) |

| Year of VA IC diagnosis | |

| Median (IQR) | 2010 (2005, 2014) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 48 (48%) |

| Male | 52 (52%) |

| Race | |

| Black | 20 (20%) |

| White | 75 (75%) |

| Asian/Pac Islander | 2 (2%) |

| Am Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (1%) |

| Unknown | 2 (2%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 6 (6%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 85 (85%) |

| Unknown | 9 (9%) |

| Inclusion in cohort | |

| Include | 84 (84%) |

| Exclude | 16 (16%) |

| Reason for exclusion (n = 16) | |

| Pelvic radiation | 5 (31%) |

| Bladder cancer | 10 (63%) |

| Cancer | 1 (6%) |

| Independent IC diagnosis (n = 84) | |

| No | 30 (36%) |

| Yes, visit | 29 (35%) |

| Yes, historical | 10 (12%) |

| Equivocal, historical | 15 (18%) |

Note: Report generated on 21SEP2016.

Abbreviations: IC, interstitial cystitis; IQR, interquartile range, VA, Veterans Affairs.

Of the 69 patients for whom a chart review could independently determine whether they had IC/BPS, 39 (57%) truly had IC/BPS according to our diagnostic criteria, while 30 (43%) did not have IC/BPS. Patients correctly diagnosed with IC/BPS were younger than patients who were misdiagnosed (median age 42 vs 56, P = .027). Gender, race, ethnicity, and year of ICD diagnosis were not associated with misdiagnosis of IC/BPS (P ≥ .3) (Table 2). Of the 30 patients who did not have IC/BPS, 13 (43%) complained only of OAB symptoms without bladder pain (Table 3). In addition, 14 (47% of the 30 pts.) never complained of bladder centric pain but had complaints of vaginal pain (four patients), chronic prostatitis (two), or nonspecified pain (eight). There was no association between gender and pain that was not bladder centric (P = .47; Table 4). However, female patients who were misdiagnosed were more likely to have OAB symptoms than males who were misdiagnosed (63% vs 21%, P = .003; Table 4).

TABLE 2.

Included patient demographics

| Equivocal (N = 15) | Non-IC (N = 30) | IC (N = 39) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at VA IC diagnosis (IQR) | 50 (37, 67) | 56 (44, 68) | 42 (35, 54) | .027a |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 8 (53%) | 16 (53%) | 24 (62%) | .750b |

| Male | 7 (47%) | 14 (47%) | 15 (38%) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 10 (71%) | 20 (69%) | 32 (82%) | .607c |

| Black | 4 (29%) | 7 (24%) | 7 (18%) | |

| Asian/Pac Islander | - | 1 (3%) | - | |

| Am Indian/Alaska Native | - | 1 (3%) | - | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | - | 3 (11%) | 2 (5%) | .568c |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 13 (100%) | 24 (89%) | 36 (95%) | |

| Year of VA IC diagnosis (IQR) | 2013 | 2010 | 2009 | .305a |

| (2008, 2014) | (2003, 2014) | (2004, 2013) |

Note: Data presented as median (IQR), or count (percent).

Abbreviations: IC, interstitial cystitis; IQR, interquartile range, VA, Veterans Affairs.

Kruskal-Wallis.

χ2 test.

Fisher exact test.

TABLE 3.

Misdiagnosed IC patient symptoms

| Equivocal | Non-IC | IC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n Females | 8 | 16 | 24 | ||

| n Males | 7 | 14 | 15 | P value | |

| Menses pain without bladder pain (females) | |||||

| 1 (13%) | – | – | .130a | ||

| Vaginal pain without bladder pain (females) | |||||

| No | 5 (100%) | 12 (75%) | 24 (100%) | .023a | |

| – | 4 (25%) | – | |||

| Prostate surgery in past 24 wk (males) | |||||

| No | 6 (100%) | 11 (85%) | 15 (100%) | .305a | |

| – | 2 (14%) | – | |||

| Prostatitis without bladder pain (males) | |||||

| No | 5 (100%) | 9 (82%) | 14 (100%) | .276a | |

| – | 2 (14%) | – | |||

| Testes pain without bladder pain (males) | |||||

| No | 4 (80%) | 10 (83%) | 15 (100%) | .167a | |

| 1 (14%) | 2 (14%) | – | |||

| Urethral stricture present (males) | |||||

| – | 1 (7%) | – | .567a | ||

| Pain but not bladder-centric (all) | |||||

| No | 8 (80%) | 14 (50%) | 39 (100%) | <.001a | |

| 2 (13%) | 14 (47%) | – | |||

| Overactive bladder symptoms without pain (all) | |||||

| No | 7 (78%) | 14 (52%) | 39 (100%) | <.001a | |

| 2 (13%) | 13 (43%) | – |

Note: Data presented as median (IQR) or count (percent).

Abbreviations: IC, interstitial cystitis; IQR, interquartile range; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Fisher Exact.

TABLE 4.

Symptoms by gender in misdiagnosed interstitial cystitis patients

| Female (N = 16) | Male (N = 14) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain but not bladder-centric | .470a | ||

| No | 8 (50%) | 6 (43%) | |

| Yes | 8 (50%) | 6 (43%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 2 (14%) | |

| Overactive bladder symptoms without pain | .003a | ||

| No | 3 (19%) | 11 (79%) | |

| Yes | 10 (63%) | 3 (21%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (19%) | 0 (0%) |

Fisher exact.

4 |. DISCUSSION

Despite the great burden of IC/BPS on public health, the diagnosis of IC/BPS remains challenging and is often subjective in current clinical practice. Overall, we found that almost half of the patients in a national VA healthcare system cohort who carried an ICD diagnosis of IC/BPS did not meet our diagnostic criteria for IC/BPS. Of the 69 patients in whom a detailed chart review could independently assign a diagnosis, 30 (43%) did not have IC/BPS. Of these patients, 13 (43%) complained only of OAB symptoms and had no pain complaints. In addition, 14 (47% of the 30) complained of other types of pain, such as vaginal pain or prostatitis related pain, but never complained of pain related to the bladder. While the clinical picture for IC/BPS is variable, according to NIH guidelines the major distinguishing feature of IC/BPS is the presence or absence of pain and the location of the pain.3,16 One of the greatest challenges to diagnosing IC/BPS is the significant overlap in symptoms between IC/BPS and other conditions such as urinary tract infection, vulvodynia and endometriosis in women, and chronic prostatitis and chronic orchialgia in men.3,16 Vulvodynia pain is localized to the vulva, while dysmenorrhea distinguishes endometriosis from IC/BPS.17 In addition, chronic prostatitis is characterized by pain in the perineum, suprapubic region, testicles or tip of the penis and is often worsened by urination or ejaculation.3 While it is possible that a patient presents with more than one of these conditions, according to the SUFU definition, if the patient never complains of “an unpleasant sensation perceived to be related to the urinary bladder” this is unlikely to be IC/BPS.3 These results indicate that, while the SUFU definition emphasizes bladder centric pain as the hallmark of IC/BPS, many patients are diagnosed with IC/BPS without this complaint. Using survey instruments, such as the Genitourinary Pain Index (GUPI), may be useful in differentiating IC/BPS pain from other pain conditions. These results have important implications for both improving clinical practice patterns with IC/BPS and estimating more accurate prevalence and incidence of IC/BPS.

The results also showed that the reason for misdiagnosis varied by gender. In women, IC/BPS was more likely to be confused with OAB when compared with men (63% vs 21%). Our results indicate that IC/BPS was overdiagnosed in patients who never complained of pain related to the bladder and more commonly so in women. In fact, nocturia, frequency, and urgency are common symptoms for both OAB and IC/BPS.17,18 As reported in the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) study, there are only two specific symptoms that separate OAB from IC/BPS-urge urinary incontinence among OAB patients and bladder-centric pain among IC/BPS patients. Patients with pure OAB do not experience bladder pain symptoms and commonly describe a fear of leakage with urgency. IC/BPS patients, contrarily, most often report an urgent need to urinate to relieve pain (rather than fear of leakage).18 These results emphasize the difficulty in making the diagnosis of IC/BPS, as well as the need for continued focus on pain symptoms when making an IC/BPS diagnosis, especially in women.

Men also had a high rate of IC/BPS overdiagnosis, but for a different reason. All 16 of the patients from the initial cohort of 100 who were misdiagnosed due to exclusionary criteria were male. The most common reasons for exclusion were bladder cancer and pelvic radiation before diagnosis. While the symptoms of radiation cystitis mimic IC/BPS, a history of pelvic radiation by definition excludes the diagnosis of IC/BPS.19 Berry et al considered both bladder cancer and radiation treatment to the pelvic area as exclusion criteria when developing a case definition for IC/BPS using data from the RICE study.18,20 As for bladder cancer, it is possible that a patient’s IC/BPS symptoms presented before the bladder cancer diagnosis, but in these cases symptoms were not reviewed as there was no way to distinguish the true etiology of the symptoms. Our results, if confirmed in future studies, indicate that, in men, radiation cystitis is often mistaken for interstitial cystitis and greater efforts should be made to consider these exclusions before making the diagnosis of IC/BPS.

The present study is limited by the retrospective nature of the cohort. It is possible that, with additional information, a more accurate diagnosis could have been made. However, we did limit our analysis to patients with sufficient data to confirm a diagnosis and excluded patients seen only by a urologist outside the VA or with a historical diagnosis which we could not confirm in the chart. We are also limited by our definition of IC/BPS. We used the AUA and SUFU definition for IC, “an unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, and discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than 6 weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes”9,11,12,21–23 and created a system to allow for flexibility of diagnosis, but the heterogeneous and subjective nature of the condition remains a limiting factor. At last, it is uncertain whether these results can be generalized to the US population as veterans may have had different stressors and exposures that affect IR/BPS risk. Patterns of care may also vary by provider type in and out of the VA system. Future research is needed to validate our work in other clinical populations and to study variations in care by provider type (urologist, generalist, allied health professionals, etc).

5 |. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we found a high rate of misdiagnosis of IC/BPS. Patients complaining of OAB symptoms with the absence of pain and patients with pain localized to areas other than the bladder are at risk of being overdiagnosed with IC/BPS. We also found that women misdiagnosed with IC/BPS were more likely to have OAB than men, while men who were misdiagnosed were more likely to have bladder cancer or radiation therapy complicating the diagnosis. These data could be used to improve prevalence estimates of IC/BPS as well as diagnostic practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge support from Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention (1U01DP006079) (SJF, JTA, JK). We wish to dedicate this study to Dr. Timothy Cunningham, who was devoted to supporting this study. May he rest in peace.

Funding information

Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention, Grant/Award Number: 1U01DP006079

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Views and opinions of and endorsements by the author(s) do not reflect those of the US Army or the Department of Defense.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, Rosetti MCO, Gao SY, Calhoun EA. Prevalence and incidence of interstitial cystitis in a managed care population. The Journal of Urology. 2005;173(1):98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordling J, Anjum F, Bade J, et al. Primary evaluation of patients suspected of having interstitial cystitis (IC). European Urology. 2004;45(5):662–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, et al. AUA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. The Journal of Urology. 2011;185(6):2162–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon LJ, Landis JR, Erickson DR, Nyberg LM, Group IS. The Interstitial Cystitis Data Base Study: concepts and preliminary baseline descriptive statistics. Urology. 1997;49(5):64–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sant GR, Hanno PM. Interstitial cystitis: current issues and controversies in diagnosis. Urology. 2001;57(6):82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moutzouris D-A, Falagas ME. Interstitial cystitis: an unsolved enigma. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2009;4(11):1844–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, Rosetti MCOK, Brown SO, Gao SY, Calhoun EA. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms in a managed care population. The Journal of Urology. 2005;174(2): 576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsons JK, Kurth K, Sant GR. Epidemiologic issues in interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2007;69(4):S5–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanno P, Levin R, Monson F, et al. Diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. The Journal of Urology. 1990;143(2):278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanno P International consultation on IC–Rome, September 2004/Forging an international consensus: progress in painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis. International Urogynecology Journal. 2005;16(1):S2–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ness TJ, Powell-Boone T, Cannon R, Lloyd LK, Fillingim RB. Psychophysical evidence of hypersensitivity in subjects with interstitial cystitis. The Journal of Urology. 2005;173(6):1983–1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warren JW, Keay SK. Interstitial cystitis. Current Opinion in Urology. 2002;12(1):69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillenwater JY, Wein AJ. Summary of the National Institute of Arthritis, Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases Workshop on Interstitial Cystitis, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, August 28–29, 1987. The Journal of Urology. 1988;140(1):203–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanno PM, Landis JR, Matthews-Cook Y, Kusek J, Nyberg L Jr. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis revisited: lessons learned from the National Institutes of Health Interstitial Cystitis Database study. The Journal of Urology. 1999;161(2):553–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry SH, Stoto MA, Elliott M, et al. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome in the United States. The Journal of Urology. 2009;181(4):20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buffington CA. Re: Symptoms of interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome and similar diseases in women: a systematic review: L. M. Bogart, S. H. Berry and J. Q. Clemens. The Journal of Urology. 2007; 177: 450–456. The Journal of Urology. 2007;178(3 Pt 1):1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogart LM, Berry SH, Clemens JQ. Symptoms of interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome and similar diseases in women: a systematic review. The Journal of Urology. 2007;177(2):450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry SH, Bogart LM, Pham C, et al. Development, validation and testing of an epidemiological case definition of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. The Journal of Urology. 2010;183(5):1848–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curhan GC, Speizer FE, Hunter DJ, Curhan SG, Stampfer MJ. Epidemiology of interstitial cystitis: a population based study. The Journal of Urology. 1999;161(2):549–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanno PM, Erickson D, Moldwin R, Faraday MM. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: AUA guideline amendment. The Journal of Urology. 2015; 193(5):1545–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanno P, Keay S, Moldwin R, Van Ophoven A. International consultation on IC-Rome, September 2004/Forging an International Consensus: progress in painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Report and abstracts. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2005;16(Suppl 1):S2–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordling J, Anjum FH, Bade JJ, et al. Primary evaluation of patients suspected of having interstitial cystitis (IC). European Urology. 2004;45(5):662–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anger JT, Zabihi N, Clemens JQ, Payne CK, Saigal CS, Rodriguez LV. Treatment choice, duration, and cost in patients with interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome. International Urogynecology Journal. 2011;22(4):395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]