Abstract

Objectives:

Michigan expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) through a federal waiver that permitted state-mandated features, including an emphasis on primary care. We investigate factors associated with Michigan primary care providers’ (PCPs) decision to accept new Medicaid patients under Medicaid expansion.

Study Design:

Statewide survey of PCPs informed by semi-structured interviews.

Methods:

After Michigan expanded Medicaid on April 1, 2014, we surveyed 2104 PCPs (including physician and non-physician providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants) caring for 12 or more Medicaid expansion enrollees (response rate = 56%) and interviewed 19 PCPs caring for Medicaid expansion enrollees from diverse urban and rural regions. Survey questions assessed PCPs’ current acceptance of new Medicaid patients.

Results:

78% of PCPs reported they were currently accepting new Medicaid patients; 58% reported having at least some influence in the decision. Factors considered very/moderately important to the Medicaid acceptance decision included: capacity to accept any new patients (69%), availability of specialists for Medicaid patients (56%), reimbursement amount (56%), psychosocial needs of Medicaid patients (50%), and illness burden of Medicaid patients (46%). PCPs accepting new Medicaid patients tended to be female, minorities, non-physician providers, internal medicine specialty, paid by salary, or working in practices with Medicaid-predominant payer mixes.

Conclusions:

After Medicaid expansion, PCPs placed importance on practice capacity, specialist availability, and patients’ medical and psychosocial needs when deciding whether to accept new Medicaid patients. In addition to reimbursement policies, policymakers should consider such factors to ensure adequate PCP capacity in states with expanded Medicaid coverage.

Keywords: Medicaid expansion, Medicaid acceptance, primary care, Affordable Care Act (ACA)

Précis:

After Medicaid expansion, PCPs placed importance on practice capacity, specialist availability, and reimbursement when deciding whether to accept new Medicaid patients.

Introduction

Provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) including Medicaid expansion continue to undergo active debate and face potentially major changes. As the state and federal governments debate the future of the ACA, it is clear that some form of expanded Medicaid coverage will remain, but likely with more state flexibility in coverage and implementation.1, 2 States will, as always, face tradeoffs between competing ways to use limited resources.3

The impact of expanded Medicaid in any form depends on several factors, but importantly on the acceptance of Medicaid by health care providers and systems. Payment has long been emphasized as a driver of physician participation in Medicaid. Prior studies have found that reimbursement level is important to health care providers’ decisions to accept Medicaid,4–6 including in the era of the ACA Medicaid expansion.7 However, it is important to carefully consider both financial and non-financial factors that may influence providers’ participation in Medicaid and other programs.8 Research since the 1980’s examined several factors associated with physician Medicaid acceptance, including characteristics of “high-share” Medicaid providers such as younger age, female gender, and non-white race.4, 5, 9–12 However, few studies have comprehensively examined which provider characteristics and practice settings may be associated with provider willingness to accept new Medicaid patients, particularly in the context of Medicaid expansion.

Since primary care providers (PCPs) provide frontline access and care to patients, understanding factors associated with an adequate supply of PCPs who accept Medicaid patients is critically important. Moreover, for PCPs already caring for Medicaid populations, what factors incentivize them to continue to accept new Medicaid patients? Michigan’s “Healthy Michigan Plan” (HMP) expanded Medicaid under the ACA through a federal Section 1115 waiver that permitted state-mandated features, including an emphasis on primary care.13 Prior studies of HMP found increased access to primary care for Medicaid patients14, 15 despite rapid enrollment in the program,16 which was consistent with trends observed in 10 other states.17, 18 However, the factors underlying this increase in PCPs’ Medicaid acceptance were unknown. This study aimed to investigate factors associated with PCPs’ decision to accept new Medicaid patients in the context of ACA Medicaid expansion.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

As part of a formal evaluation under contract with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) and required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for the Section 1115 waiver, we conducted a statewide survey of PCPs regarding their experiences with HMP enrollees, new practice approaches and innovation adopted or planned in response to HMP, and future plans regarding acceptance and care of HMP patients. As an evaluation of a public program, the University of Michigan and MDHHS Institutional Review Boards deemed the study exempt.

SURVEY SAMPLING

We included PCPs who cared for at least 12 HMP patients in the sample (further details of sampling in Appendix A).

SURVEY DEVELOPMENT

The survey included standard measures of PCP demographic, professional and practice characteristics, as well as items from prior surveys on decision making related to Medicaid patients.11, 19 New items related to PCPs’ decisions to accept Medicaid patients in the context of the state Medicaid expansion were developed based on qualitative interviews. Items were subsequently cognitively pretested with two PCPs (1 physician from a safety net clinic and 1 PA from a private practice) to ensure understanding prior to survey administration. The final survey was also pretested with one PCP to ensure appropriate timing and flow.

Qualitative Interviews.

To guide survey development and interpretation, we conducted 19 semi-structured interviews with PCPs caring for Medicaid/HMP patients between December 2014 and April 2015. These interviews were conducted in five geographic regions across Michigan, purposefully selected to include racial/ethnic diversity and a mix of urban, suburban and rural communities: City of Detroit, Western Michigan, Central Lower Michigan, Northeastern Michigan, and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Interviewees included both physicians and non-physician providers (i.e., NPs/PAs) who worked at small private practices, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), free/low-cost clinics, hospital-based practices, or rural practices (Appendix Table 1).

Interview topics included: a) provider awareness of patients’ insurance and experiences caring for HMP patients; b) PCP involvement in decision-making about whether to accept Medicaid/HMP patients; and c) factors that may affect PCPs’ Medicaid acceptance decisions in the future, including knowledge of reimbursement changes such as the Medicaid primary care rate bump to Medicare rates in 2013-2014.

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each transcript was reviewed iteratively by at least two members of the research team, with in depth coding and thematic analysis20, 21 performed using Dedoose software (http://www.dedoose.com).

SURVEY ADMINISTRATION

The survey was initially mailed to the PCP sample (N=4,322) in June 2015 and included a personalized cover letter describing the project, a fact sheet about the Healthy Michigan Plan, a paper copy of the survey, a $20 bill, and a postage-paid return envelope. The cover letter also gave information on the option to complete the survey online. Two additional mailings were sent to nonrespondents in August and September 2015. Data from mailed and online surveys returned by November 1, 2015 were included in the analysis.

SURVEY OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

The dependent variable was PCPs’ current acceptance of new Medicaid or HMP patients (“Are you currently accepting new patients with … [Medicaid; Healthy Michigan Plan; Private insurance; Medicare; No insurance (i.e., self-pay)]?”). In addition to standard PCP and practice characteristics, survey items measured independent variables of PCP attitudes regarding the importance of various patient- and practice-level factors in their practice’s decision to accept new Medicaid/HMP patients (e.g., reimbursement amount, practice capacity to accept any new patients, specialist availability, and illness needs of Medicaid/HMP patients), and their experiences caring for and expressed commitment to caring for underserved populations.

SURVEY DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics were used to report PCP characteristics, current acceptance of new patients and responses to other individual survey items. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association of independent variables with the dependent variable of continued PCP acceptance of new Medicaid patients (Yes/No).

PCP personal, professional and practice characteristics with statistically significant associations at p<0.01 were included as covariates in multivariable analyses, except for cases with expected collinearity (e.g., non-physician provider variable included but not specialty; payer mix variable included but not payment arrangement). For inclusion of items assessing attitudes toward underserved patients in the regression analyses, we created an index across all underserved attitudes items and calculated a score based on agreement level to multiple items (score of 1 was assigned to a response of “strongly disagree”, 2 for “disagree”, 3 for “neither agree nor disagree”, 4 for “agree” and 5 for “strongly agree”). Scores for individual items were summed to produce a scaled score for which higher numbers represented stronger agreement with commitment to caring for the underserved. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA version 13 or 14.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

CHARACTERISTICS OF PCP SURVEY RESPONDENTS

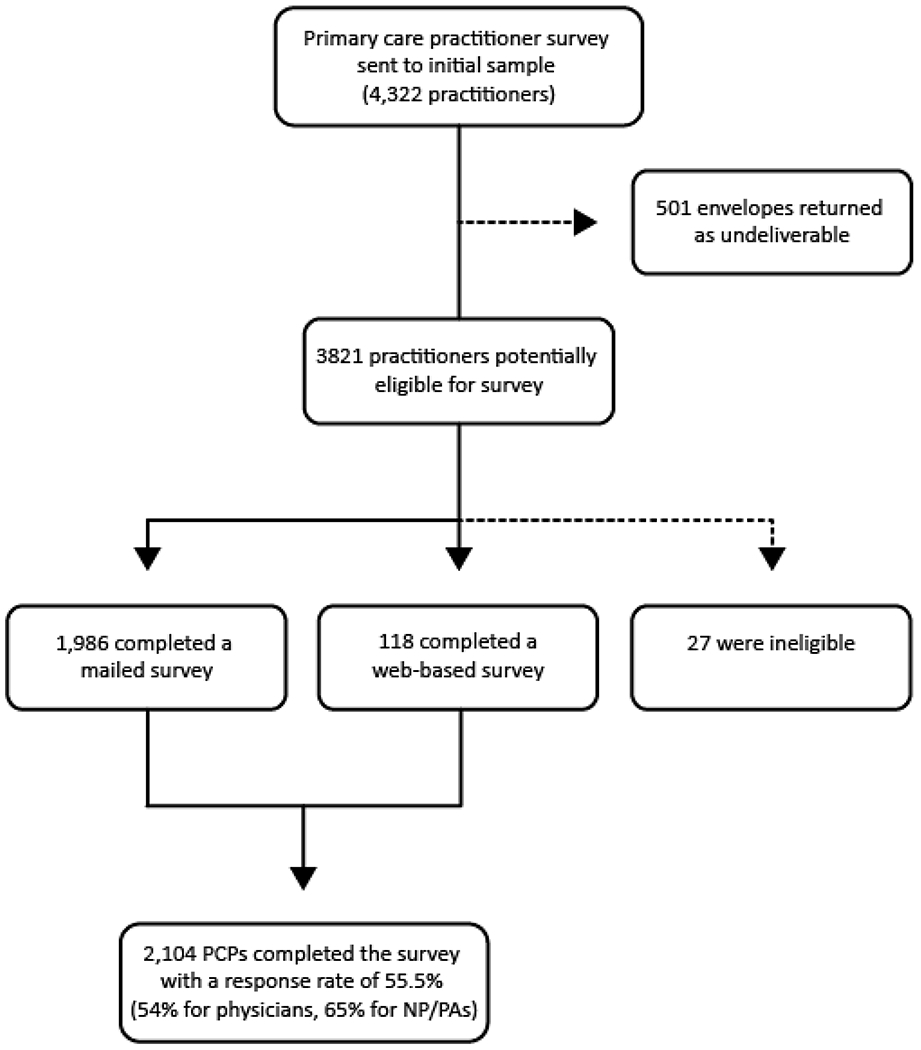

After excluding PCPs with undeliverable addresses (501) and who were ineligible (27, e.g., retired, moved out of state), the final response rate was 56% (54% for physicians, 65% for NPs/PAs; N=2,104). See Appendix Figure 1 for flowchart of survey response rates. There were no significant differences between respondents and nonrespondents with regard to gender, age, number of affiliated Medicaid managed care plans and practice setting in a FQHC; more PCPs with internal medicine specialty were nonrespondents (see Appendix Table 2 for comparison of PCP survey respondents and nonrespondents).

Approximately half (45%) of respondents were female and 79% were white (Table 1). Non-physician providers (NPs/PAs) represented 17% of respondents. Family medicine (53%) and internal medicine (27%) were the most common specialties, and 82% of respondents were board certified. Most (74%) had been in practice for at least 10 years. Fifteen percent practiced in an FQHC and 35% had a payer mix that was predominantly Medicaid.

Table 1.

Personal, Professional, and Practice Characteristics of PCP Survey Respondents

| n (N=2,104) |

% | |

|---|---|---|

|

Personal

characteristics | ||

| Gender, Female | 936 | 45 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1583 | 79 |

| Black/African American | 93 | 5 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 224 | 11 |

| Other | 86 | 4 |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 46 | 2 |

|

Professional

characteristics | ||

| Provider type, non-physician (NP/PA) | 357 | 17 |

| Specialty | ||

| Family medicine | 1123 | 53 |

| Internal medicine | 574 | 27 |

| Nurse practitioner | 192 | 9 |

| Physician assistant | 165 | 8 |

| Other | 50 | 2 |

| Board Certified | 1695 | 82 |

| Years in practice | ||

| <10 years | 520 | 26 |

| 10-20 years | 676 | 34 |

| >20 years | 810 | 40 |

|

Practice

characteristics | ||

| Small practice (≤ 5 providers)a | 1157 | 57.5 |

| Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) | 311 | 15 |

| Predominant payer mixb | ||

| Private | 661 | 35 |

| Medicaid/Healthy Michigan Plan | 677 | 35 |

| Medicare | 421 | 22 |

| Uninsured | 12 | 1 |

| Mixed | 141 | 7 |

| Payment arrangement | ||

| Fee-for-service | 784 | 38 |

| Salary | 946 | 45 |

| Capitation | 44 | 2 |

| Mixed | 275 | 13 |

| Other | 40 | 2 |

| Urbanicityc | ||

| Urban | 1584 | 75 |

| Suburban/Rural | 520 | 25 |

Dichotomized at sample median

Composite variable of all current payers: payer is considered predominant for the practice if >30% of physician’s patients have this payer type and <30% of patients have any other payer type. “Mixed” includes practices with more than one payer representing >30% of patients or practices with <30% of patients for each payer type.

Zip codes and county codes were linked to the US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service 2013 Urban Influence Codes to classify regions into urban (codes 1 and 2), suburban (codes 3-7), and rural (codes 8-12) designations.

PCPs’ ACCEPTANCE OF NEW PATIENTS

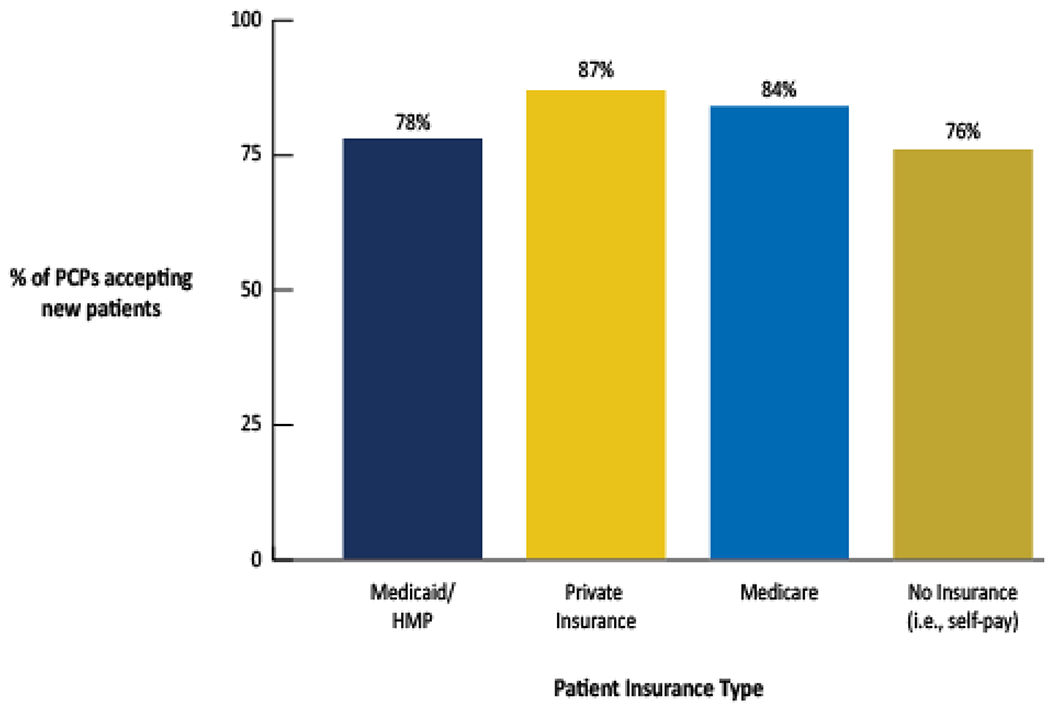

While all survey respondents had established patients with Medicaid/HMP coverage based on the survey sampling, 78% reported accepting new Medicaid or HMP patients compared with 87% accepting new patients with private insurance, 84% Medicare, and 76% no insurance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PCPs’ Acceptance of New Patients by Insurance Typea

a1575 (78%) of PCP respondents reported accepting new patients with either Healthy Michigan Plan (HMP) or Medicaid.

ATTITUDES INFLUENCING PCPs’ MEDICAID ACCEPTANCE DECISION

Most PCP survey respondents reported having at least some influence in the decision to accept or not accept Medicaid or HMP patients: 23% reported “The decision is entirely mine,” 14% reported “I have a lot of influence,” 21% reported “I have some influence,” and 43% reported “I have no influence”.

In interviews, PCPs described influences on the Medicaid acceptance decision at various levels (see themes in Table 2). At the provider level, the illness burden and psychosocial needs of prospective Medicaid patients influenced PCPs’ decision about whether to accept them, particularly for patients with complex chronic pain or mental health needs. At the practice level, the decision to accept new patients depended on the practice’s capacity to provide sufficient care to established patients, including timeliness of appointments and ability to provide high-quality care. At the health system level, PCPs’ decision-making depended on the resources and administrative structure of their health system, including whether specialists were available to see Medicaid patients. Lastly, with regard to the policy environment, while most PCPs thought reimbursement was important, many lacked knowledge of the 2013-2014 AC A primary care rate bump or other payment details yet continued to accept new Medicaid patients.

Table 2.

Interview Themes related to Factors Influencing PCPs’ Decision-Making on Acceptance of Medicaid Patients

| Influence Theme | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Provider level | |

| Illness burden and psychosocial needs of prospective Medicaid patients |

“There are days when

we’ll look at each other and it’s like, ‘I

think we’ve got enough people like that.’ It’s

like the person who takes the energy of dealing with six ordinary

people.” -PCP in rural health clinic |

| Practice level | |

| Practice capacity |

“It has to do with what our

capacity is. So looking at schedules, looking at next appointments,

are we able to adequately care for the patients that we ’re

currently responsible for?” -PCP in urban free/low-cost clinic |

| Health system level | |

| Resources and administrative structures, including specialist availability |

“While our ability to care for

[Medicaid patients] has dramatically expanded, our ability to tap

into our disjointed healthcare system in terms of specialty care

maybe hasn’t changed a whole lot … private specialists

don’t really care if they ’re uninsured or if they

have Healthy Michigan.” -PCP in urban federally qualified health center “I think the actual decision as to whether to accept Healthy Michigan patients … is made at the health system level … I wouldn’t really be involved in making that decision, nor would most of my clinic leadership.” -PCP in urban hospital-based practice |

| Policy environment | |

| Knowledge and attitudes toward reimbursement |

“For our clinic, [reimbursement

amount] plays no role in whether we accept more Medicaid patients

… we ’re gonna serve that population and take care of

them … We ’ll do whatever reasonably we can do to get

paid for that, but that doesn’t make or break the decision

…” -PCP in urban free/low-cost clinic “If they were to all of a sudden say, ‘Okay, we ’re only going to reimburse 40% or 50% of what we used to,’ that would be enough to put me out of business. So I would think twice about seeing those patients then, but as long as they continue the way they have been for the last six years that I’ve owned the clinic, I don’t see making any changes.” -PCP in rural health clinic |

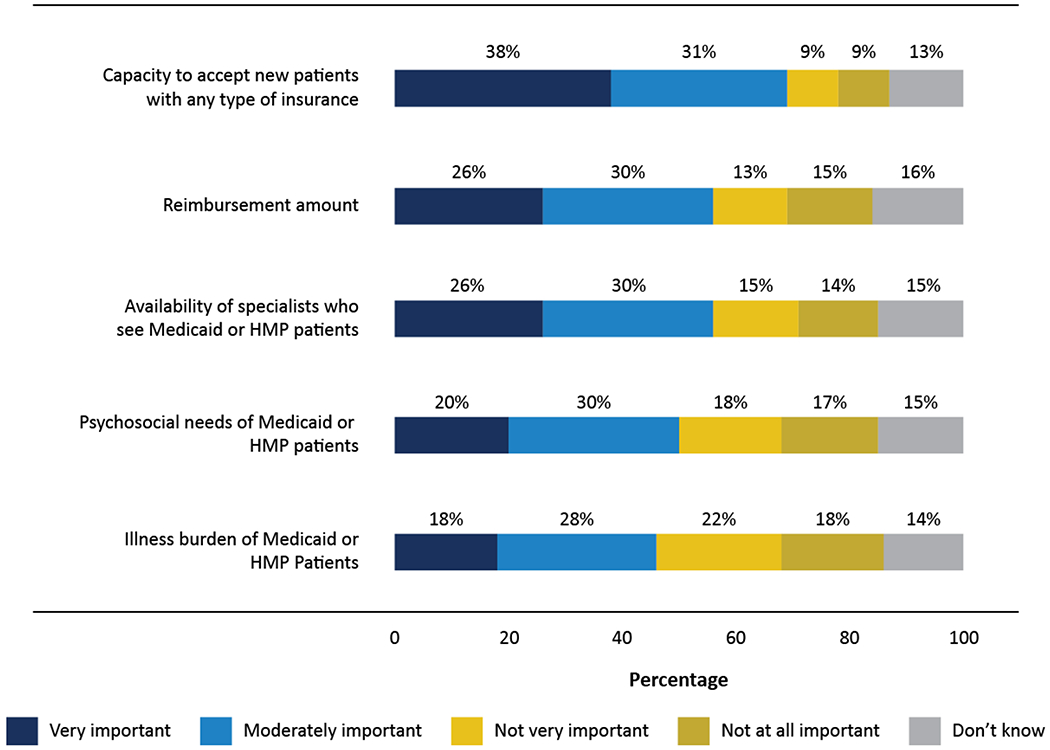

Based on these themes identified in the qualitative interviews, we asked PCP survey respondents to rate the importance of several patient- and practice-level factors to their practice’s decision to accept new Medicaid or HMP patients (“Please indicate the importance of each of the following for your practice’s decision to accept new Medicaid or Healthy Michigan Plan patients,” Figure 2). Factors considered very/moderately important to the Medicaid acceptance decision included: capacity to accept new patients with any type of insurance (69%), availability of specialists who see Medicaid patients (56%), reimbursement amount (56%), psychosocial needs of Medicaid patients (50%), and illness burden of Medicaid patients (46%).

Figure 2.

Importance of Various Factors to PCPs’ Decision to Accept New Medicaid Patientsa

aRespondents were asked to “Please indicate the importance of each of the following for your practice’s decision to accept new Medicaid or Healthy Michigan Plan patients”.

We also asked PCP survey respondents about their prior experience and attitudes toward caring for poor or underserved patients. More than half of (57%) respondents reported providing care in the past three years in a setting that serves poor and underserved patients with no anticipation of being paid. Nearly three-quarters (73%) felt a responsibility to care for patients regardless of their ability to pay, and nearly three-quarters (72%) agreed or strongly agreed that all practitioners should care for some Medicaid patients (see Appendix Table 3 for full descriptive statistics of PCP attitudes about caring for underserved patients).

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH PCPs’ MEDICAID ACCEPTANCE

In bivariate analyses, PCP survey respondents were more likely to accept new Medicaid patients were younger, female, racial minorities, internal medicine specialty, non-physician providers (NPs or PAs), paid by salary, or working in FQHCs, rural practices, or practices with integrated mental health care or Medicaid-predominant payer mixes (Table 3). Multivariable analyses largely confirmed bivariate analyses: PCP respondents who were female (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.32, 95% CI 1.01-1.72), racial minorities (aOR3.46 [95% CI 1.45-8.25] for black, aOR 1.84 [95% CI 1.21-2.80] for Asian), non-physician providers (aOR 2.21 compared with physicians, 95% CI 1.32-3.71), internal medicine specialty (aOR 1.47 compared with family medicine, 95% CI 1.09-1.97), paid by salary (aOR 2.09 compared with fee-for-service, 95% CI 1.58-2.77), or working in practices with Medicaid-predominant payer mixes (aOR 7.31 compared with private-predominant payer mix, 95% CI 5.05-10.57) or other non-private payer mixes were more likely to accept new Medicaid patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis of Association of PCP and Practice Characteristics with Medicaid Acceptancea

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio of Medicaid Acceptance (OR, 95% CI) | Adjustedb Odds Ratio of Medicaid Acceptance (aOR, 95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

|

Personal and

Professional characteristics | ||

| Female Gender | 1.59 (1.28-1.98)d | 1.32 (1.01-1.72)c |

| Race | ||

| White | [ref] | [ref] |

| Black/African American | 3.93 (1.80-8.57)c | 3.46 (1.45-8.25)c |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.76 (1.20-2.58)c | 1.84 (1.21-2.80)c |

| Other | 1.94 (1.04-3.62)c | 1.79 (0.84-3.80) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | 1.88 (0.79-4.48) | 1.54 (0.56-4.22) |

| Years in Practice | ||

| <10 years | [ref] | [ref] |

| 10-20 years | 0.69 (0.51-0.93)c | 0.87 (0.62-1.22) |

| >20 years | 0.51 (0.38-0.68)d | 0.82 (0.58-1.15) |

| Non-physician provider (vs. physician provider) | 4.78 (3.09-7.40)d | 2.21 (1.32-3.71)c |

| Specialty | ||

| Family medicine | [ref] | [ref] |

| Internal medicine | 1.43 (1.12-1.83)c | 1.47 (1.09-1.97)c |

| Nurse practitioner | 7.81 (3.95-15.45)d | 3.53 (1.64-7.61)c |

| Physician Assistant | 4.07 (2.32-7.16)d | 1.83 (0.94-3.56) |

| Other | 2.86 (1.21-6.79)c | 2.02 (0.75-5.45) |

| Board Certified | 0.57 (0.42-0.77)d | 0.92 (0.64-1.32) |

| Payment arrangement | ||

| Fee-for-service | [ref] | [ref] |

| Salary predominant | 3.02 (2.36-3.85)d | 2.09 (1.58-2.77)d |

| Mixed payment | 1.34 (0.98-1.84) | 1.43 (0.99-2.07) |

| Other payment arrangements | 2.44 (1.01-5.93)c | 1.33 (0.51-3.49) |

|

PCP

attitudes | ||

| Capacity very/moderately important | 0.53 (0.41-0.68)d | 0.59 (0.44-0.79)d |

| Reimbursement very/moderately important | 0.64 (0.51-0.79)d | 0.86 (0.67-1.10) |

| Specialist availability very/moderately important | 0.95 (0.76-1.17) | 1.11 (0.86-1.42) |

| Illness burden of patients very/moderately important | 1.02 (0.83-1.27) | 1.03 (0.81-1.32) |

| Psychosocial needs of patients very/moderately important | 1.10 (0.89-1.37) | 1.14 (0.89-1.45) |

| Provided care to the underserved in past 3 years | 1.64 (1.33-2.03)d | 1.35 (1.05-1.73)c |

| Expressed commitment to caring for underserved | 1.16 (1.13-1.19)d | 1.14 (1.11-1.18)d |

|

Practice

characteristics | ||

| Small practice with ≤5 providers (vs. large practice) | 1.18 (0.95-1.47) | 1.27 (0.99-1.63) |

| Urban (vs. rural/suburban) | 0.69 (0.53-0.89)c | 0.97 (0.72-1.31) |

| Federally qualified health center | 2.40 (1.66-3.47)d | 1.08 (0.70-1.65) |

| Mental health co-location | 1.99 (1.42-2.79)d | 1.16 (0.79-1.71) |

| Predominant payer mix | ||

| Private insurance | [ref] | [ref] |

| Medicaid/Healthy Michigan Plan | 8.64 (6.14-12.15)d | 7.31 (5.05-10.57)d |

| Medicare | 1.94 (1.47-2.55)d | 2.04 (1.52-2.73)d |

| Mixed | 3.32 (2.05-5.37)d | 3.76 (2.24-6.30)d |

Each cell represents a separate bivariate or multivariable logistic regression model.

Adjusted for covariates of gender, years in training, physician vs. non-physician provider, board certification, urbanicity, federally qualified health center status, predominant payer mix, except for when independent variable included in list.

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

Regarding PCP attitudes, in bivariate analyses, PCP survey respondents were less likely to accept new Medicaid patients if they deemed overall capacity to accept new patients was very/moderately important or reimbursement was very/moderately important. Not surprisingly, PCPs were also more likely to accept new Medicaid patients if they had provided prior care to the underserved or expressed a greater commitment to caring for the underserved. In multivariable analyses, we again found that PCPs who had previously provided care to underserved patients (aOR 1.35, 95% CI 1.05-1.73) or who expressed stronger commitment to caring for the underserved (OR 1.14 for each point in composite score, 95% CI 1.11-1.18) were more likely to accept new Medicaid patients. PCPs were less likely to accept new Medicaid patients if they deemed overall capacity to accept new patients very/moderately important (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.44-0.79).

We then repeated the bivariate and multivariable analyses for the sub-group of PCP survey respondents who indicated they had at least some influence in the decision to accept Medicaid patients. The findings were similar to analyses with the full sample (data not shown).

Discussion

The ACA’s Medicaid expansion has been associated with increased access to care nationally,7, 17, 18, 23–29 and increased Medicaid acceptance among PCPs in Michigan,14 even after expiration of the 2013-2014 primary care rate increase of Medicaid fees to Medicare levels.15 In our study, we found that PCP demographics, salary structure, history of caring for the underserved and perceived practice capacity were all associated with continued acceptance of new Medicaid patients.

Our findings on provider characteristics associated with increased likelihood of Medicaid acceptance were consistent with literature that pre-dated the ACA Medicaid expansion. Specifically, female gender, non-white race and non-physician professional training (nurse practitioner or physician assistant) have been associated with greater provider Medicaid acceptance in earlier periods.4, 5, 9, 12, 30, 31 These findings suggest that demographic characteristics of the primary care workforce can influence access for Medicaid patients, and that integrating non-physician providers in primary care practices may be beneficial to ensuring access for Medicaid patients. In fact, an earlier Michigan study found that an increase in Medicaid primary care appointment availability after HMP was associated with rising proportions of appointments offered with NPs or PAs, suggesting that non-physician providers contributed to improved access.15

We also found that PCPs in safety net settings and other practices with Medicaid-predominant payer mixes were more likely to continue accepting new Medicaid patients, confirming findings from prior studies.6, 10, 11, 32, 33 Unlike prior studies,6, 7 in our adjusted models, PCP attitudes toward reimbursement were not significantly associated with the likelihood of Medicaid acceptance. Whether this relates to PCPs’ lack of knowledge of reimbursement changes during the rate bump period, as found in our interviews, or other factors is uncertain. Combined with our findings that experience and commitment to caring for the underserved were associated with PCP acceptance of Medicaid, these results suggest that PCPs accepting Medicaid patients do so at least in part out of a sense of professional duty.34 To encourage greater provider acceptance of Medicaid, policymakers should consider promoting experiences caring for underserved populations during professional training to broaden the pipeline of future health care providers accepting Medicaid.35

Like other studies, we found that concerns about practice capacity were associated with lower odds of accepting new Medicaid patients.11 Our qualitative findings demonstrated that PCPs were concerned both about scheduling patients with themselves and with specialists who would accept Medicaid. To overcome PCPs’ reported worries about having sufficient time to see their Medicaid patients or having access to Medicaid-accepting specialists for these patients, practice-level innovations targeting appointment scheduling, team-based care, and integration of specialists such as mental health professionals may also facilitate PCPs’ continued acceptance of Medicaid patients.

This study has several potential limitations. First, measures are self-reported and prone to social desirability and other survey biases. Particularly regarding willingness of health care providers to accept new Medicaid patients, survey self-report may overestimate actual acceptance of new patients.36 Second, the sample included only PCPs who cared for at least 12 HMP enrollees. Decision making regarding acceptance of new patients may differ for PCPs with fewer or no Medicaid patients or for specialists. Third, we developed a new set of survey items not used in previous studies that assess PCP attitudes toward various factors related to their Medicaid acceptance decision. However, these items were developed based on prior literature and our qualitative interviews with PCPs caring for HMP patients, and were cognitively pretested with physician and non-physician PCPs serving HMP patients to ensure understanding and accuracy of responses. Fourth, this study was conducted within the context of one state’s Medicaid expansion. It is possible that other factors may be relevant to PCPs’ Medicaid acceptance decision in other states, such as Medicaid reimbursement rates.

With continued innovation in Medicaid policy at the state and federal level, identifying provider and practice factors that promote Medicaid acceptance among PCPs will be even more important. This study confirmed several of the same factors considered important to PCPs in prior studies – practice capacity, specialist availability, medical and psychosocial needs of Medicaid patients – but in the new context of Medicaid expansion. In addition, PCPs in this study placed less emphasis on reimbursement, perhaps because many served in salaried positions, or because they instead emphasized professional commitment to caring for the poor and underserved. To maintain primary care access for low-income patients with Medicaid, future efforts should focus on enhancing the diversity of the PCP workforce, encouraging health care professional training in underserved settings, and promoting practice-level innovations in scheduling and integration of specialist care.

Take-Away Points:

After Michigan expanded Medicaid, factors considered important to PCPs when deciding whether to accept new Medicaid patients included: capacity to accept any new patients (69%), availability of specialists for Medicaid patients (56%), reimbursement amount (56%), psychosocial needs of Medicaid patients (50%), and illness burden of Medicaid patients (46%).

PCPs accepting new Medicaid patients tended to be female, minorities, non-physician providers, internal medicine specialty, paid by salary, or working in practices with Medicaid-predominant payer mixes.

In addition to reimbursement policies, policymakers should consider such factors to ensure adequate PCP capacity in states with expanded Medicaid coverage.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: The study was funded by a contract from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) to the University of Michigan to conduct an evaluation of the Healthy Michigan Plan, as required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) through a Section 1115 Medicaid waiver.

APPENDIX

SURVEY SAMPLING

The PCP sample was drawn from the MDHHS Data Warehouse, which stores data generated from encounters on all Medicaid and HMP enrollees and their providers, including provider demographics, specialty, practice setting, and health plan participation. From the warehouse, 7,360 National Provider Identifier (NPI) numbers were identified as the assigned PCP for at least one HMP managed care enrollee in April 2015, one year after the HMP launch. We considered PCPs with at least 12 assigned members eligible for the survey based on a number of patients the study team determined was meaningful and at a threshold that was within our evaluation budget. This criterion allowed us to select for the full census of PCPs with adequate experience caring for HMP patients (an average of one HMP enrollee month). Thus, 2,813 PCPs with fewer than 12 assigned members were excluded. Of the remaining 4,547 PCPs, exclusions included: 25 with an NPI entity code that did not reflect an individual provider (20 organizational NPIs, 4 deactivated, and 1 invalid), 161 with only pediatric specialty, 4 University of Michigan physicians involved in the HMP evaluation, and 35 with out-of-state addresses greater than 30 miles from the Michigan border. After exclusions, 4,322 PCPs (3686 physicians and 636 nurse practitioners [NPs]/physician assistants [PAs]) remained in the survey sample.

Appendix Table 1.

Characteristics of PCP Interviewees (N=19)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 | 63 |

| Female | 7 | 37 |

| Professional Characteristics | ||

| Provider Type | ||

| Physician | 16 | 84 |

| Non-physician (NP/PA) | 3 | 16 |

| Specialty | ||

| Family Medicine | 14 | 74 |

| Internal Medicine | 2 | 11 |

| Nurse Practitioner (NP) | 1 | 5 |

| Physician Assistant (PA) | 2 | 11 |

| Years in Practice | ||

| <10 years | 5 | 26 |

| 10-20 years | 6 | 32 |

| >10 years | 8 | 42 |

| Practice Characteristics | ||

| Practice type | ||

| Federally qualified health center (FQHC) | 5 | 26 |

| Large/hospital-based practice | 3 | 16 |

| Free/low-cost clinic | 2 | 11 |

| Small, private practice | 7 | 37 |

| Rural health clinic | 2 | 11 |

| Urbanicity | ||

| Urban | 12 | 63 |

| Rural | 7 | 37 |

Appendix Figure 1.

Flowchart of PCP Survey Response Rates

Appendix Table 2.

Characteristics of PCP Survey Respondents and Nonrespondents

| Respondents N=2104 (%) |

Nonrespondents N=1690 (%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 45 | 44 | 0.55 |

| Male | 55 | 56 | |

| Age | |||

| Birth year 1970 or earlier | 71 | 70 | 0.32 |

| Birth year 1971 or later | 29 | 31 | |

| Number of Medicaid managed care plans | |||

| 1 plan | 21 | 20 | 0.48 |

| 2 plans | 27 | 26 | |

| 3 or more plans | 52 | 54 | |

| Practice setting | |||

| Federally qualified health center | 15 | 15 | 0.86 |

| Other setting | 85 | 85 | |

| Specialty | |||

| Family medicine/general practice | 55 | 51 | |

| Internal medicine | 27 | 36 | <0.001 |

| Nurse practitioner/physician assistant | 17 | 11 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 |

Appendix Table 3.

PCP Attitudes About for Underserved Patients

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neither | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All practitioners should care for some Medicaid/Healthy Michigan Plan patients | 941 (45%) | 555 (27%) | 346 (17%) | 150 (7%) | 81 (4%) |

| It is my responsibility to provide care for patients regardless of their ability to pay | 874 (42%) | 642 (31%) | 282 (14%) | 190 (9%) | 78 (4%) |

| Caring for Medicaid/Healthy Michigan Plan patients enriches my clinical practice | 418 (20%) | 590 (29%) | 746 (36%) | 246 (12%) | 67 (3%) |

| Caring for Medicaid/Healthy Michigan Plan patients increases my professional satisfaction | 379 (18%) | 543 (26%) | 794 (39%) | 260 (13%) | 88 (4%) |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is the pre-publication version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication in The American Journal of Managed Care (AJMC). This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The editors and publisher of AJMC are not responsible for the content or presentation of the prepublication version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to it (eg, correspondence, corrections, editorials, etc) should go to www.ajmc.com or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors were supported by a contract from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services to conduct an evaluation of the Healthy Michigan Plan, Michigan’s Medicaid expansion. There are no other relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Congressional Budget Office. Cost Estimate: H.R. 1628, American Health Care Act of 2017. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/hr1628aspassed.pdf Accessed May 24, 2017.

- 2.Congressional Budget Office. Cost Estimate: H.R. 1628, Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52849 Accessed June 26, 2017.

- 3.Rosenbaum S The American Health Care Act and Medicaid: changing a half-century federal-state partnership. Health Affairs Blog [Internet]. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/03/10/the-american-health-care-act-and-medicaid-changing-a-half-century-federal-state-partnership/ Accessed March 10, 2017.

- 4.Komaromy M, Lurie N, Bindman AB. California physicians’ willingness to care for the poor. Western J Med. 1995;162(2):127–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perloff JD, Kletke P, Fossett JW. Which physicians limit their Medicaid participation, and why. Health Serv Res. 1995;30(1):7–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff. 2012;31(8):1673–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polsky D, Richards M, Basseyn S, et al. Appointment availability after increases in Medicaid payments for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(6):537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phipps-Taylor M, Shortell SM. More than money: motivating physician behavior change in accountable care organizations. Milbank Q. 2016;94(4):832–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perloff JD, Kletke PR, Neckerman KM. Physicians’ decisions to limit Medicaid participation: determinants and policy implications. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1987;12(2):221–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham P, May J. Medicaid patients increasingly concentrated among physicians. Tracking report /Center for Studying Health System Change. 2006(16):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommers AS, Paradise J, Miller C. Physician willingness and resources to serve more medicaid patients: perspectives from primary care; physicians. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. Vol 12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geissler KH, Lubin B, Marzilli Ericson KM. Access is not enough: Characteristics of physicians who treat Medicaid patients. Med Care. 2016;54(4):350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayanian JZ. Michigan’s approach to Medicaid expansion and reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1773–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tipirneni R, Rhodes KV, Hayward RA, Lichtenstein RL, Reamer EN, Davis MM. Primary care appointment availability for new Medicaid patients increased after Medicaid expansion in Michigan. Health Aff. 2015;34(8):1399–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tipirneni R, Rhodes KV, Hayward R, et al. Primary care appointment availability, wait times, and the importance of non-physician providers during the first year of Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(6):427–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayanian JZ, Clark SJ, Tipirneni R. Launching the Healthy Michigan Plan - the first 100 days. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1573–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes KV, Basseyn S, Friedman AB, Kenney GM, Wissoker D, Polsky D. Access to primary care appointments following 2014 insurance expansions. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polsky D, Candon M, Saloner B, et al. Changes in primary care access between 2012 and 2016 for new patients with medicaid and private coverage. JAMA IM. 2017; 177(4):588–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niess M, et al. Colorado Medicaid specialist survey. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patton MQ. How to use qualitative methods in evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss A and Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques (3rd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage; (2008) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carman KG, Eibner C, Paddock SM. Trends in health insurance enrollment, 2013–15. Health Aff. 2015;34(6): 1044–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, Musco T. Changes in self-reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015;314(4):366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shartzer A, Long SK, Anderson N. Access To care and affordability have improved following Affordable Care Act implementation; Problems remain. Health Aff. 2016;35(1): 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ. Both the ‘private option’ and traditional Medicaid expansions improved access to care for low-income adults. Health Aff. 2016;35(1):96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benitez JA, Creel L, Jennings J. Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion showing early promise on coverage and access to care. Health Aff. 2016; 35(3): 528–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wherry LR, Miller S. Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions: A quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2016; 164(12):795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and access to care during the first 2 Years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buerhaus PI, DesRoches CM, Dittus R, Donelan K. Practice characteristics of primary care nurse practitioners and physicians. Nursing Outlook. 2015;63(2): 144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Everett CM, Thorpe CT, Palta M, Carayon P, Gilchrist VJ, Smith MA. Division of primary care services between physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners for older patients with diabetes. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(5):531–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams EK, Herring B. Medicaid HMO penetration and its mix: did increased penetration affect physician participation in urban markets? Health Serv Res. 2008;43(1 Pt 2):363–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richards MR, Saloner B, Kenney GM, Rhodes KV, Polsky D. Availability of new Medicaid patient appointments and the role of rural health clinics. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(2):570–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Medical Association. Code of medical ethics 11.1.4. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Connell TF, Ham SA, Hart TG, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. A National Longitudinal Survey of Medical Students’ Intentions to Practice Among the Underserved. Acad Med. 2018;93(l):90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coffman JM, Rhodes KV, Fix M, Bindman AB. Testing the validity of primary care physicians’ self-reported acceptance of new patients by insurance status. Health Serv Res. 2016; 51 (4): 1515–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]