Abstract

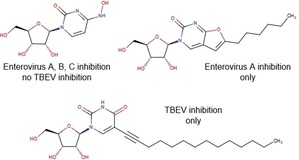

The rational design of broad‐spectrum antivirals requires data on antiviral activity of compounds against multiple viruses, which are often not available. We have developed a panel of (+)ssRNA viruses composed of Enterovirus and Flavivirus genera members allowing to study these activity spectra. Antiviral activity profiling of a set of nucleoside analogues revealed N 4‐hydroxycytidine as an efficient inhibitor of replication of coxsackieviruses and other enteroviruses, but ineffective against tick‐borne encephalitis virus. Furano[2, 3‐d]pyrimidine nucleosides with n‐pentyl or n‐hexyl tails showed selective inhibition of Enterovirus A representatives. 5‐(Tetradec‐1‐yn‐1‐yl)‐uridine showed selective inhibition of tick‐borne encephalitis virus at the micromolar level.

Keywords: antiviral agents, enterovirus, nucleoside analogues, structure-activity relationships, tick-borne encephalitis virus

Antiviral activity spectrum assessment showed that broad‐spectrum antiviral N4‐hydroxycytidine inhibits reproduction of enteroviruses, but not tick‐borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), a flavivirus. Furano[2, 3‐d]pyrimidine nucleosides suppressed only Enterovirus A species members, Enterovirus A71 and Coxsackievirus A16, but not other enteroviruses or TBEV. 5‐(Tetradec‐1‐yn‐1‐yl)‐uridine, on the other hand, inhibited TBEV only.

Introduction

Nucleoside analogues represent a broad class of small molecule compounds extensively studied as promising broad‐spectrum antivirals.1 Compounds with nucleoside scaffold are implied to interfere with nucleic acid processing machinery, suppressing viral replication. This strategy is used in the treatment of hepatitis B virus (HBV, DNA virus with reverse transcription, Hepadnaviridae family) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV, RNA virus with reverse transcription, Retroviridae family) infections.1 It seems especially attractive for viruses with RNA genomes, replicated by viral RNA‐dependent RNA polymerases. These enzymes are unique for viruses, thus a superior selectivity with less side effects is achievable for nucleoside‐based antivirals targeting these enzymes. On the other hand, viral RNA polymerases are rather similar to each other, and it is highly possible that the same compound may inhibit several of them. Despite numerous nucleoside analogues being available, spectrum of their antiviral activity remains poorly studied, with most compounds non‐systematically tested against one or two viruses.

Enteroviruses are small non‐enveloped RNA viruses widely circulating all over the world and causing diseases mostly in children. The need for small molecule drugs against enteroviruses is justified by diversity of these viruses and ability to cause outbreaks, the range of syndromes they cause and increasing number of neuroinfections with severe CNS damage, such as poliomyelitis, encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, and acute flaccid myelitis.2 High variability of enteroviral antigens prohibits development of a universal anti‐enteroviral vaccine, and more conserved replication machinery opens the possibility to create pan‐enteroviral drugs.2 Several dozens of enterovirus serotypes are grouped into the genus Enterovirus: species Enterovirus A to D and Rhinovirus A to C include human pathogens. According to our searches in ChEMBL database, containing annotated biological activity data for more than 1.3 million compounds,3 2406 different compounds were tested against at least one enterovirus, but only 32 of them were simultaneously assessed against Enterovirus A, Enterovirus B, and Enterovirus C species representatives. These 32 compounds interact with capsid proteins,4 host targets,5 or 3C protease6 and do not contain nucleoside‐like scaffolds. Although literature coverage by ChEMBL is not comprehensive, systematic studies of nucleoside antiviral activity against different enteroviruses are sporadic and do not show a consistent picture.

Nucleosides with hydrophobic substituents in nucleobase moiety were previously shown to be efficient inhibitors of enterovirus A71 (Enterovirus A) reproduction, but most of them did not inhibit reproduction of polioviruses (Enterovirus C) nor coxsackievirus B3 and echovirus 11 (Enterovirus B).7 We have also shown that some of these compounds may inhibit the reproduction of tick‐borne encephalitis virus (TBEV),8 which is an enveloped RNA arbovirus endemic for the Northern Eurasia. Transmitted by infected ticks, this virus may cause severe neurological symptoms in a form of encephalitis or meningoencephalitis, eventually leading to death or serious disabilities. Over ten thousand cases are registered annually despite the availability of vaccines, and small molecule compounds comprise a promising and highly expected treatment option.9

To extend our knowledge on the spectrum of antiviral activity of nucleoside analogues with hydrophobic substituents in the nucleobases, we performed profiling of antiviral activity of ten diverse nucleoside analogues and derivatives against TBEV strain Absettarov (genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae) and a panel of enterovirus isolates of 2012–2014, representing three major species of genus Enterovirus (family Picornaviridae, order Picornavirales): Enterovirus A (enterovirus A71, coxsackievirus A16), Enterovirus B (coxsackieviruses B1 and A9, echoviruses 6 and 30), Enterovirus C (strain Sabin 1 poliovirus type 1). We found that in most cases the antiviral activity appeared only against Enterovirus A species representatives.

Results and Discussion

We selected for our study ten nucleoside analogues with modifications in the nucleic base or sugar moiety presented in the Table 1. Compounds 1–3 are commonly known nucleoside analogs.10 Compounds 6–10 were described by us earlier,11 whereas 2‐thio‐5‐modified‐6‐azauridines 4 and 5 were synthesized for the first time.

Table 1.

Structures, toxicity, and antiviral activity of nucleoside analogues.

|

Structure |

PEK CC50 [μM][a] |

RD CC50 [μM][b] |

TBEV EC50 [μM] |

EV EC50 [μM][c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1‐(β‐d‐ribofuranosyl)isocarbostyryl (1) |

>50 (24 h); >50 (7 d) |

>125 (24 h); 73 (7 d) |

> 50 |

> 125 (EVA71, CVB1, PV1) |

|

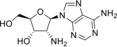

2’‐Amino‐2’‐deoxyadenosine (2) |

>50 (24 h); 26 (7 d) |

73 (24 h); 20 (7 d) |

> 50 |

> 125 (EVA71, CVB1, PV1) |

|

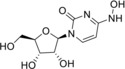

N 4‐Hydroxycytidine (3) |

>50 (24 h); >50 (7 d) |

73 (24 h); 73 (7 d) |

> 50 |

28±13 (EVA71); 5.41 (CVA16); 18.41 (CVA9); 7.74 (CVB1); 18.41 (ECHO30); 73.66 (ECHO6); 36.83 (PV1) |

|

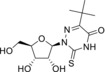

2‐Thio‐5‐(tert‐butyl)‐6‐azauridine (4) |

NDa |

104 (24 h); 104 (7 d) |

> 50 |

> 125 (EVA71, CVB1, PV1) |

|

2‐Thio‐5‐phenyl‐6‐azauridine (5) |

ND |

>125 (24 h); >125 (7 d) |

> 50 |

> 125 (EVA71, CVB1, PV1) |

|

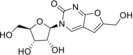

3‐(β‐d‐Ribofuranosyl)‐6‐hydroxymethyl‐2,3‐dihydrofurano[2, 3‐d]pyrimidin‐2‐one (6) |

ND |

>125 (24 h); >125 (7 d) |

> 50 |

> 125 (EVA71, CVB1, PV1) |

|

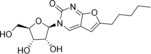

3‐(β‐d‐Ribofuranosyl)‐6‐pentyl‐2,3‐dihydrofurano[2, 3‐d]pyrimidin‐2‐one (7) |

ND |

73 (24 h); 73 (7 d) |

> 50 |

18±12 (EVA71); 4.6 (CVA16); > 125 (CVA9, CVB1, ECHO30, ECHO6, PV1) |

|

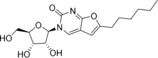

3‐(β‐d‐Ribofuranosyl)‐6‐hexyl‐2,3‐dihydrofurano[2, 3‐d]pyrimidin‐2‐one (8) |

ND |

73 (24 h); 36 (7 d) |

> 50 |

16±9 (EVA71); 3.26 (CVA16); > 125 (CVA9, CVB1, ECHO30, ECHO6, PV1) |

|

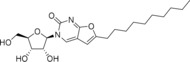

3‐(β‐d‐Ribofuranosyl)‐6‐decyl‐2,3‐dihydrofurano[2, 3‐d]pyrimidin‐2‐one (9) |

>50 (24 h); >50 (7 d) |

>125 (24 h); >125 (7 d) |

> 50 |

> 125 (EVA71, CVB1, PV1) |

|

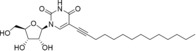

5‐(Tetradec‐1‐yn‐1‐yl)‐uridine (10) |

>50 (24 h); >50 (7 d) |

73 (24 h); 20 (7 d) |

9.4±0.4 |

> 73 (EVA71, CVB1, PV1) |

|

N 6‐Benzyladenosine (12 a) |

ND |

9.21 (24 h); 9.21 (7 d) |

> 50 |

2.5±0.2 (EVA71); 0.92±0.24 (CVA16); 7.75±3.15 (CVB1); 11.1±1.9 (ECHO30); 10.15±0.95 (PV1) |

|

dUY11 (11 a) |

>50 (24 h); >50 (7 d)[e] |

ND |

0.024±0.013[e] |

ND |

[a] PEK, porcine embryo kidney cells. [b] RD, rhabdomyosarcoma cells. [c] EV, enteroviruses. [d] ND, not determined. [e] Data from ref. 12.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Antiviral activity and cytotoxicity were determined using previously described methods for TBEV (plaque reduction test12) and enteroviruses (cytopathic effect inhibition test13). Enterovirus activity screening was performed against enterovirus A71 (EVA71), coxsackievirus B1 (CVB1), and poliovirus (PV1); active compounds were additionally assessed against the remaining viruses. All tested compounds showed acceptable levels of acute (24 h) and chronic (7 d) cytotoxicity (Table 1). Fifty % effective concentrations (EC50) of the compounds are given in Table 1. N 6‐Benzyladenosine was used as the positive control for anti‐enterovirus activity, and previously published data for dUY11, obtained according to the same protocol, served as TBEV inhibition positive control.12

Compounds 1, 2, 4, and 5 did not show any antiviral activity in the tests. For compound 2 (2′‐amino‐2′‐deoxyadenosine, 2‐AA) this observation is in line with the previous study,14 where replication inhibition was observed for measles virus, but not for echovirus 7, nor herpes simplex virus 2, vesicular stomatitis virus, and BK virus. Compound 3, N 4‐hydroxycytidine (NHC), on the contrary, revealed itself as a pan‐enterovirus reproduction inhibitor with a preference for coxsackieviruses independently of the enterovirus species assignment. Nevertheless, this compound did not inhibit TBEV reproduction at 50 μM concentration. In the previous studies NHC was shown to inhibit the replication of viruses with various genomes and replication cycles: (+)ssRNA genomic bovine viral diarrhea (BVDV) and hepatitis C (HCV) viruses, both belonging to Flaviviridae family,15 severe acute respiratory syndrome‐associated coronavirus,16 norovirus,17 chikungunya virus;18 (‐)ssRNA genomic Ebola virus,19 and DNA genomic vaccinia, monkeypox, and cowpox viruses (family Poxviridae).20 However, it is not active against HIV‐1, hepatitis B virus, and herpes simplex viruses.15 Such a profile of antiviral activity suggests that this compound may target host proteins, as well as viral ones. This compound is also a well‐known mutagen mimicking cytidine,10c and fast replicating viruses may be more susceptible to its incorporation into genome than cells.

Time‐of‐addition studies against EVA71 and PV1 were performed for NHC to further clarify its mechanism of action. Cells were incubated with NHC or DMSO for 1 h, then virus pre‐incubated with NHC or DMSO was added and left for 1 h for sorption and entry, and then cultural medium with NHC or DMSO was added. Virus was harvested after a single replication cycle and total virus yields were determined. The schemes of the experiment and results are given in Table 2. Significant reduction of virus yields in the schemes D, E, and F suggests that NHC targets the stages of reproduction that occur after entry, i. e., replication and/or virion assembly, and does not prevent viral entry. This target stage is expected for nucleoside analogues.

Table 2.

Time‐of‐addition assessment for NHC with enteroviruses.

|

Experiment Scheme |

Supposed Target |

Addition of components |

Virus Yield (logTCID50/mL) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

‐1 – 0 h |

0 – 1 h |

1 – 7 h |

EVA71 |

PV1 |

||

|

A |

Control |

DMSO |

DMSO + virus |

DMSO |

4.5±0.18 |

4.0±0.53 |

|

B |

Cell |

NHC |

DMSO + virus |

DMSO |

4.13±0.18 |

3.44±0.09 |

|

C |

Virion |

DMSO |

NHC + virus |

DMSO |

4.19±0.27 |

3.63±0.35 |

|

D |

After entry |

DMSO |

DMSO + virus |

NHC |

2.5±0.01 |

1.44±0.09 |

|

E |

Cell & after entry |

NHC |

DMSO + virus |

NHC |

2.5±0.01 |

1.13±0.53 |

|

F |

Virion & after entry |

DMSO |

NHC + virus |

NHC |

2.75±0.35 |

1.75±0.35 |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Furano[2, 3‐d]pyrimidine nucleosides 6‐9 and their synthetic precursor analogue 10 11 showed a specific pattern of antiviral activity. These compounds were previously assessed for inhibition of reproduction of HCV and BVDV (RNA viruses, Flaviviridae family).9 The only active compound in these assays was 9, with EC50 of 1.9 μM against BVDV and moderate HCV inhibition at 100 μM, without inhibition of RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase NS5B and RNA helicase NS3. Analogues with alkyn‐1‐yl tails were tested against varicella zoster virus and human cytomegalovirus (DNA viruses, Herpesvirales order), and the most potent ones had C10 and C12 tails.21 For non‐enveloped RNA genomic enteroviruses an optimal chain length for alkyl also exists: compounds 7 and 8 with C5 and C6 alkyls are the only active ones, and elongation (9) or removal (6) of the chain lead to inactivity. This pattern also suggests that activity is unlikely to be attributed to the detergent properties of the molecule, given that only viruses belonging to Enterovirus A species, EVA71 and CVA16, are susceptible to these compounds. Such species selectivity profile was also observed for other classes of hydrophobic nucleosides, e. g., N 6‐substituted adenosines [A. A. Orlov, V. E. Oslovsky, S. N. Mikhailov, L. I. Kozlovskaya, D. I. Osolodkin, manuscript in preparation]. This selectivity may be attributed to sequence differences of replication machinery proteins on the species level.22

Compared with N 6‐benzyladenosine, which had been earlier shown to efficiently inhibit reproduction of enteroviruses,7 compounds 3, 7, and 8 show a much more acceptable toxicity level. Whereas the CC50/EC50 ratio for N 6‐benzyladenosine in our hands is no larger than 10 (observed for CVA16), for the same virus this ratio is 16 for 7 and 22 for 8. It is worth noting that the toxicity level itself is much lower for furano[2, 3‐d]pyrimidine nucleosides than for N 6‐benzyladenosine, and it opens the way for the further design of more potent congeners keeping the same low toxicity.

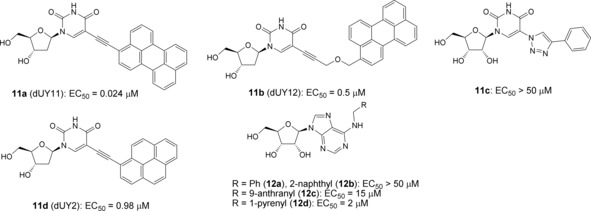

The only compound that suppressed reproduction of enveloped RNA genomic TBEV was 10. Structure of this compound falls into the same line with so‐called rigid amphipathic fusion inhibitors (RAFI, 11, Figure 1), typical representatives of which differ from 10 in hydrophobic moiety: instead of a long alkyl, an ethynyl connects a perylenyl moiety to uracil in RAFIs.12,23 RAFI mechanism of action is supposed to realize through the incorporation of the perylene moiety into the viral membrane leading to membrane fusion prevention due to the shape restrictions or singlet oxygen production.24 Incorporation of a flexible linker between perylene and nucleoside (11 b) instead of ethynyl (11 a) in our previous studies led to EC50 drop from two‐digit nanomolar values to micromolar ones.12 Change or even removal of nucleoside moiety does not impair activity of RAFIs, but substitution of perylene by phenyl (11 c) or 2‐pyrenyl (11 d) does.23 Compound 10 does not contain a perylene core, bearing a C12 n‐alkyl instead, and it shows slightly lower activity than RAFI with the flexible linker, justifying again the importance of perylene fragment. Activity profile of compounds 7–9 against TBEV, HCV, and BVDV (all Flaviviridae family), suggests that the ability of a compound to incorporate into the viral membrane does not guarantee antiviral activity of the compound, and the geometry of nucleoside head is important for alkylated nucleosides. Similar peculiarities were already observed for anti‐TBEV activity of N 6‐substituted adenosines with hydrophobic substituents,8 where introduction of alkyls did not lead to the inhibition of viral reproduction, whereas large aryls (12) positively affected the activity.

Figure 1.

Anti‐TBEV activity of nucleosides with hydrophobic substituents.8,12,23

Conclusions

Screening of antiviral activity of diverse nucleoside analogues revealed new data on activity of N 4‐hydroxycytidine, which showed pan‐enterovirus inhibition without effect on TBEV, and furano[2, 3‐d]pyrimidine nucleosides with long alkyl tails, selectively inhibiting replication of Enterovirus A species members. These data improved understanding of structure‐activity relationships of congeneric series, offering new opportunities in the design of broad‐spectrum antivirals.

Supporting Information Summary

Experimental Section is available as Supporting Information, containing details of compound preparation and biological experiments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Drs. O. E. Ivanova, T. P. Eremeeva, and G. G. Karganova for providing the viruses for this work; Y. Rogova, I. Antonova, O. Baykova, and V. Chernikov for technical support. N6‐Benzyladenosine sample was kindly provided by Dr. Sergey N. Mikhailov (Engelhargt Institute of Molecular Biology).

This study was supported by Russian Science Foundation (grant no. 16‐15‐10307 — antiviral activity determination and SAR analysis) and Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant no. 17‐04‐00536 — compound synthesis). BSL‐3 facilities, virus isolation and collection maintenance were supported by the state research funding for Chumakov FSC R&D IBP RAS.

L. I. Kozlovskaya, A. D. Golinets, A. A. Eletskaya, A. A. Orlov, V. A. Palyulin, S. N. Kochetkov, L. A. Alexandrova, D. I. Osolodkin, ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 2321.

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Academician Nikolay S. Zefirov (1935‐2017)

References

- 1.

- 1a. Jordheim L. P., Durantel D., Zoulim F., Dumontet C., Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 447–464; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Debing Y., Neyts J., Delang L., Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 28, 596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Linden L. Van der, Wolthers K. C., Kuppeveld F. J. M. van, Viruses 2015, 7, 4529–4562; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Bauer L., Lyoo H., Schaar H. M. van der, Strating J. R. P. M., Kuppeveld F. J. M. van, Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017, 24, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gaulton A., Bellis L. J., Bento A. P., Chambers J., Davies M., Hersey A., Light Y., McGlinchey S., Michalovich D., Al-Lazikani B., Overington J. P., Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1100–D1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Chang C.-S., Lin Y.-T., Shih S.-R., Lee C.-C., Lee Y.-C., Tai C.-L., Tseng S.-N., Chern J.-H., J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3522–3535; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Oberste M. S., Moore D., Anderson B., Pallansch M. A., Pevear D. C., Collett M. S., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 4501–4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. MacLeod A. M., Mitchell D. R., Palmer N. J., Poël H. V. de, Conrath K., Andrews M., Leyssen P., Neyts J., ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 585–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lacroix C., George S., Leyssen P., Hilgenfeld R., Neyts J., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5814–5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Arita M., Wakita T., Shimizu H., J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 2518–2530; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Tararov V. I., Tijsma A., Kolyachkina S. V., Oslovsky V. E., Neyts J., Drenichev M. S., Leyssen P., Mikhailov S. N., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 90, 406–413; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Drenichev M. S., Oslovsky V. E., Sun L., Tijsma A., Kurochkin N. N., Tararov V. I., Chizhov A. O., Neyts J., Pannecouque C., Leyssen P., Mikhailov S. N., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 111, 84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Orlov A. A., Drenichev M. S., Oslovsky V. E., Kurochkin N. N., Solyev P. N., Kozlovskaya L. I., Palyulin V. A., Karganova G. G., Mikhailov S. N., Osolodkin D. I., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1267–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taba P., Schmutzhard E., Forsberg P., Lutsar I., Ljøstad U., Mygland Å., Levchenko I., Strle F., Steiner I., Eur. J. Neurol. 2017, 24, 1214–e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Vorbrüggen H., Bennua B., Tetrahedron. Lett. 1978, 19, 1339–1342; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Imazawa M., Eckstein F., J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 2039–2041; [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Popowska E., Janion C., Nucleic Acids Res. 1975, 2, 1143–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ivanov M. A., Ivanov A. V., Krasnitskaya I. A., Smirnova O. A., Karpenko I. L., Belanov E. F., Prasolov V. S., Tunitskaya V. L., Aleksandrova L. A., Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2008, 34, 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Orlov A. A., Chistov A. A., Kozlovskaya L. I., Ustinov A. V., Korshun V. A., Karganova G. G., Osolodkin D. I., Med. Chem. Commun. 2016, 7, 495–499. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sedenkova K. N., Dueva E. V., Averina E. B., Grishin Y. K., Osolodkin D. I., Kozlovskaya L. I., Palyulin V. A., Savelyev E. N., Orlinson B. S., Novakov I. A., Butov G. M., Kuznetsova T. S., Karganova G. G., Zefirov N. S., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 3406–3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taguchi F., Imatani Y., Nagaki D., Nakagawa A., Omura S., J. Antibiot. 1981, 34, 313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stuyver L. J., Whitaker T., McBrayer T. R., Hernandez-Santiago B. I., Lostia S., Tharnish P. M., Ramesh M., Chu C. K., Jordan R., Shi J., Rachakonda S., Watanabe K. A., Otto M. J., Schinazi R. F., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 244–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barnard D. L., Hubbard V. D., Burton J., Smee D. F., Morrey J. D., Otto M. J., Sidwell R. W., Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2008, 15, 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Costantini V. P., Whitaker T., Barclay L., Lee D., McBrayer T. R., Schinazi R. F., Vinjé J., Antivir. Ther. 2012, 17, 981–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ehteshami M., Tao S., Zandi K., Hsiao H.-M., Jiang Y., Hammond E., Amblard F., Russell O. O., Merits A., Schinazi R. F., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02395-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reynard O., Nguyen X.-N., Alazard-Dany N., Barateau V., Cimarelli A., Volchkov V. E., Viruses 2015, 7, 6233–6240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ivanov M. A., Antonova E. V., Maksimov A. V., Pigusova L. K., Belanov E. F., Aleksandrova L. A., Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2006, 71, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Robins M. J., Miranda K., Rajwanshi V. K., Peterson M. A., Andrei G., Snoeck R., Clercq E. De, Balzarini J., J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. in M. S. Oberste Group B Coxsackieviruses (Eds. S. Tracy, M. S. Oberste, K. M. Drescher), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aralov A. V., Proskurin G. V., Orlov A. A., Kozlovskaya L. I., Chistov A. A., Kutyakov S. V., Karganova G. G., Palyulin V. A., Osolodkin D. I., Korshun V. A., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.

- 24a. Colpitts C. C., Ustinov A. V., Epand R. F., Epand R. M., Korshun V. A., Schang L. M., J. Virol. 2013, 87, 3640–3654; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24b. Vigant F., Hollmann A., Lee J., Santos N. C., Jung M. E., Lee B., J. Virol. 2014, 88, 1849–1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary