Abstract

BACKGROUND

Careful selection and testing of plasma reduces the risk of blood‐borne viruses in the starting material for plasma‐derived products. Furthermore, effective measures such as pasteurization at 60°C for 10 hours have been implemented in the manufacturing process of therapeutic plasma proteins such as human albumin, coagulation factors, immunoglobulins, and enzyme inhibitors to inactivate blood‐borne viruses of concern. A comprehensive compilation of the virus reduction capacity of pasteurization is presented including the effect of stabilizers used to protect the therapeutic protein from modifications during heat treatment.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

The virus inactivation kinetics of pasteurization for a broad range of viruses were evaluated in the relevant intermediates from more than 15 different plasma manufacturing processes. Studies were carried out under the routine manufacturing target variables, such as temperature and product‐specific stabilizer composition. Additional studies were also performed under robustness conditions, that is, outside production specifications.

RESULTS

The data demonstrate that pasteurization inactivates a wide range of enveloped and nonenveloped viruses of diverse physicochemical characteristics. After a maximum of 6 hours' incubation, no residual infectivity could be detected for the majority of enveloped viruses. Effective inactivation of a range of nonenveloped viruses, with the exception of nonhuman parvoviruses, was documented.

CONCLUSION

Pasteurization is a very robust and reliable virus inactivation method with a broad effectiveness against known blood‐borne pathogens and emerging or potentially emerging viruses. Pasteurization has proven itself to be a highly effective step, in combination with other complementary safety measures, toward assuring the virus safety of final product.

ABBREVIATIONS

- B19V

human parvovirus B19

- BoHV‐1

bovine herpesvirus 1

- BVDV

bovine viral diarrhea virus

- C1‐INH

C1 inhibitor concentrate

- CPV

canine parvovirus

- DHBV

duck hepatitis B virus

- EHV‐1

equine herpesvirus 1

- H1N1, H5N1

influenza virus A

- HHV‐5

human herpesvirus 5

- HSV

herpes simplex virus

- LACV

La Crosse virus

- LOD

detection limit

- MVM

minute virus of mice

- PRV

pseudorabies virus (strain Phylaxia/Bartha)

- RF(s)

reduction factor(s)

- SARS‐CoV

SARS coronavirus

- SFV

Semliki Forest virus

- SINV

Sindbis virus

- TBEV

tick‐borne encephalitis

- TGEV

transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus

- WNV

West Nile virus

- YFV

yellow fever virus

- ZIKV

Zika virus

Studies on inactivation of viruses in biologics were initially triggered after 23,000 cases of hepatitis were reported in US Armed Forces personnel in 1942 associated with the administration of certain lots of yellow fever vaccine, stabilized with non–heat‐treated human serum.1 Subsequently, the effectiveness of pasteurization as a virus inactivation technique was clinically demonstrated in human volunteers who received either a pasteurized or non–heat‐treated dose of human serum albumin (HSA) spiked with plasma containing infectious hepatitis B virus (HBV). Subjects who received the pasteurized HBV‐spiked HSA displayed no clinical signs of infection, as monitored by liver function assays, in contrast to the subjects who received the non–heat‐treated HBV‐spiked HSA.2 As plasma fractionation techniques improved, coagulation factors, immunoglobulins, and enzyme inhibitor concentrates were isolated at industrial scale from large volumes of pooled plasma. Although these therapeutic products provided life‐saving and life‐sustaining therapeutic options for patients, they also intermittently transmitted blood‐borne viruses,3, 4 especially HBV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Therefore, methods that had a high capacity to inactivate and/or remove viruses were integrated in the industrial manufacturing process of plasma‐derived products. The first reliable virus inactivation method, pasteurization (heat treatment in aqueous solution at 60°C for 10 hr), to effectively inactivate HBV and HCV (at that time called non‐A/non‐B hepatitis virus) in coagulation factor concentrates was studied and implemented at Behringwerke (a predecessor company of CSL Behring) in the late 1970s and early 1980s by employing suitable stabilizers and conditions to permit pasteurization without modifying the product, for example, formation of neoantigens or activated factors. As no cell culture assay system for HBV and non‐A/non‐B hepatitis virus was available, the capacity of the pasteurization step to inactivate these hepatitis viruses was assessed in chimpanzees5 or in ducklings.6 After HIV was known to be transmitted by blood transfusion and some plasma‐derived products, studies were performed using cell culture systems to document the heat sensitivity of HIV.7

Hemovigilance studies demonstrated the effectiveness of the pasteurization step introduced in the manufacturing process of a Factor (F)VIII/von Willebrand factor (FVIII/VWF) concentrate to prevent the transmission of HBV, HCV (non‐A/non‐B hepatitis virus),8 and HIV9 at the time when HCV was not a known characterized virus10 and when no donor screening assays were available for HIV.11, 12

Virus validation guidelines were ultimately developed and issued by the European authorities, requiring manufacturers to carry out studies to demonstrate the capacity, reliability, and effectiveness of the manufacturing processes to inactivate and/or remove viruses potentially present in the starting material (plasma pool for fractionation).13, 14, 15 These guidelines required a systematic evaluation of the virus reduction potential of manufacturing process steps in virus validation studies employing relevant and model viruses with a wide range of physicochemical properties.

Despite the common usage of pasteurization there is, to date, no comprehensive published overview on the effectiveness of pasteurization on the inactivation of a wide range of blood‐borne and model viruses in various plasma‐derived products in the presence of different stabilizer compositions available. This summary presents data of more than 25 years of virus validation studies including virus inactivation kinetics performed both at target and at the edge of, or outside, the manufacturing specifications to assess robustness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The efficacy of virus inactivation by pasteurization was investigated in virus validation studies performed according to the regulatory guidelines.14, 15 The stabilizer compositions for each product during pasteurization are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Stabilizer composition to protect desired therapeutic protein from modification during pasteurizationa

| Product intermediate | Sucrose† | Glycine† | Potassium acetate (g/L)† | Sorbitol (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| API | ++ | NA | S | NA |

| ATIII (Kybernin) | S | S | NA | NA |

| C1‐INH | S | S | NA | NA |

| Fibrinogen | S | – – | NA | NA |

| F IX/FX | + | – | NA | NA |

| FVIII (Beriate) | S | – | NA | NA |

| FVIII (Monoclate) | ++ | NA | S | NA |

| FXIII | S | S | NA | NA |

| IMIG (Beriglobin) | S | S | NA | NA |

| PCC | + | – | NA | NA |

| Thrombin | + | – | NA | NA |

| VWF/FVIII | S | S | NA | NA |

| ATIII (Thrombotrol)c | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| IVIG/IMIG (Intragam) | NA | NA | NA | 30 |

Further compounds like NaCl, CaCl2, EDTA, citrate, heparin, ATIII, ammonium sulfate, or ethanol may be included in low concentrations in the stabilized solution due to previous manufacturing steps or may be deliberately added to protect the desired plasma protein.

“Standard concentration” (S): approx. 500 g sucrose/kg solution, 2 mol glycine/L, or 6% potassium acetate/L; higher or lower amount stated as ++, +, –, – –, respectively.

Citrate as stabilizer.

NA = not applicable.

The following viruses and respective cell lines (Table S1, available as supporting information in the online version of this paper) were used in the pasteurization studies: human parvovirus B19 (B19V), UT7/epo‐S1; bovine herpesvirus 1 (BoHV‐1), FROv; bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), FROv/BT; canine parvovirus (CPV), CrFK/KL; duck HBV (DHBV), ducklings and in vitro; encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV), Vero; equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV‐1), Vero; herpes simplex virus (HSV‐1), PH‐2; pandemic swine influenza virus (H1N1); highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1), MDCK; hepatitis A virus (HAV), RhK/BSC‐1; human herpesvirus 5 (HHV‐5), MRC5; HIV, Jurkat/MT‐4/C8166; La Crosse virus (LACV), Vero 1008; minute virus of mice (MVM), A9; pseudorabies virus (PRV), PH‐2/Vero; SARS coronavirus (SARS‐CoV), Vero E6; Semliki Forest virus (SFV), PH‐2; Sindbis virus (SINV), PH‐2; tick‐borne encephalitis (TBEV), A549; transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV), FSHo; West Nile virus (WNV), PH‐2; Yellow Fever virus (YFV), PH‐2; and Zika virus (ZIKV), PH‐2.

Virus spiking stocks were derived from virus master and working banks. The cell culture supernatants containing the virus harvest (commonly cell culture medium without fetal bovine serum) were collected once a cytopathic effect had been detected. The virus stocks were clarified by low‐speed centrifugation to remove cell debris and aliquots were stored frozen at –70°C or below. Where higher‐titer virus stocks were required, further concentration methods such as gradient centrifugation were employed. An initial titer of 4.5 log or greater cell culture infectious dose 50% (CCID50)/mL for all viruses studied was attained after spiking product intermediates.

High‐titer virus stocks were spiked into aliquots of at least two different lots of production intermediates and the pasteurization step was performed according to manufacturing specifications in laboratories specially designed for handling viruses. To assess robustness in general, studies at or outside the manufacturing specifications were performed: 1) decreased temperature (58°C), 2) increased stabilizer concentration (up to 110% after spiking), 3) product intermediate without stabilizers, and/or 4) stabilizer excipient composition without plasma protein.

The laboratory scale of the pasteurization step was representative of the production scale for each specific product, as it met the respective process variables of the manufacturing scale, for example, temperature (60 ± 1°C), incubation time (10 [+1] hours), stabilizer composition (product specific composition of excipients), and concentration (commonly target of 100% of stabilizer used in the manufacturing process by adjusting the stabilizer concentrations taking into account the virus spike volumes). The virus reduction factors (RFs) demonstrated are, therefore, predictive for the manufacturing process scale.

Typically, process intermediates were obtained from the commercial manufacturing process, spiked with virus, mixed thoroughly, divided into tubes, and immersed in a water bath at 60°C ± 1°C. Commonly, stabilizers were added to the process intermediates, prior to virus spiking, such that after virus spiking (not exceeding 10% of the volume of the production intermediate) the stabilizer concentrations were at 99% to 100% of the manufacturing specifications. Samples were removed at various time points, titrated, and assayed using the appropriate virus/cell assay system (Table S1). DHBV, not a virus belonging to the standard panel of viruses, was studied in ducklings.6 Temperatures were monitored by calibrated thermocouples placed into control tubes containing similar volumes of pasteurization intermediate.

Virus titrations were performed immediately when the test samples were generated. The virus titration was performed in a standard microplate assay. The samples to be assayed and controls, for example, positive assay controls, were serially diluted in cell culture medium. The infectivity titer ± standard error of each sample was calculated according to the Spearman‐Kärber method. For lowering the detection limit (LOD), up to 10 mL of spiked and pasteurized, undiluted test sample was inoculated in cell culture flasks to test for infectious virus (large‐volume testing). The 95% confidence limits of a titration were within ±0.5 log. The virus RF was generally reported in one of two ways. Where no infectivity was detected in any of the replicate runs (infectivity level below the LOD as indicated by “≥”), the largest RF was selected as the demonstrated RF was limited only by the virus load in the spiked starting material and the LOD of the assay. Where at least one of the replicate runs resulted in residual infectivity, the mean of the RFs was calculated.

Cytotoxicity and interference of the product intermediate on the capacity of viruses to infect cells was evaluated and, where observed, mitigated by diluting samples. Noninoculated cells served as negative controls and spiked nonpasteurized intermediate served as positive controls.

RESULTS

All titers used for calculation of the virus RFs were obtained under conditions where no matrix interference (≤1.0 log) on assay performance or cytotoxicity of the product intermediate was observed.

Virus inactivation in HSA products

HSA is not stabilized by components affecting the inactivation kinetics of a range of viruses but only by caprylate and N‐acetyltryptophan. An effective (i.e., virus RFs in the order of 4 log or greater) virus reduction capacity could be demonstrated for the viruses studied covering a wide range of human pathogenic viruses or their specific model viruses; no residual infectivity was observed at the latest after 6 hours of pasteurization. The animal parvovirus, CPV, showed resistance to heat treatment, in contrast to the relevant human pathogenic virus B19V (Table 2).

Table 2.

Virus inactivation by pasteurization of HSA

| Albumin concentration | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4%/5% | 20% | 25% | |

| Virus | Virus RF (log)/time to no detectable infectivity (hr) | ||

| HIV | ≥6.4/2 | ≥6.7/1 | ≥6.6/0.5 |

| BVDVa | ≥9.0/6 | ≥9.1/4 | ≥8.2/2 |

| PRV | ≥7.6/0.5 | ≥7.5/1 | ≥7.2/0.5 |

| WNV | ND | ND | ≥8.6/0.5 |

| HAVb | ≥6.9/2 | ≥6.9/6 | ≥6.6/4 |

| CPVठ| 1.7/10 | 1.2/10 | 1.7/10 |

| DHBV | ≥6.6/2 | ≥2.8/1 | ND |

| B19V | ≥4.3/1 | ≥4.0/1 | ND |

SINV: inactivation in 4% albumin, at least 6.4 log/0.5 hr; in 20% albumin, at least 6.5 log/0.5 hr.

HAV substrain 18f: inactivation in 4% albumin, 4.4 log/10 hr.

CPV: inactivation in 4% albumin, 3.1 log within 10 hr.

CPV: residual infectivity detectable at 10 hr.

ND = not determined.

Virus inactivation in stabilized product intermediates

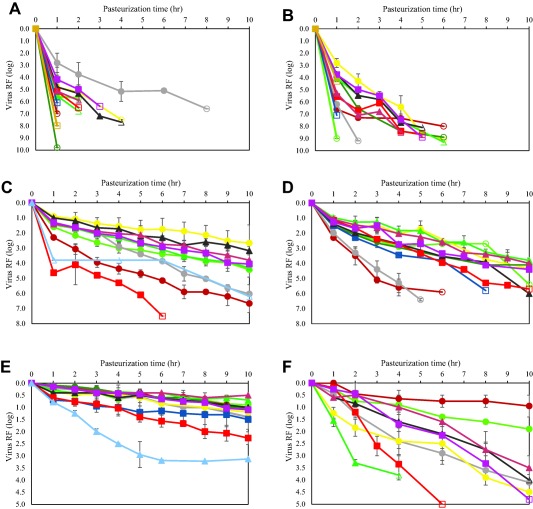

The virus reduction capacities of pasteurization in inactivating HIV, BVDV, PRV, HAV, CPV, and B19V in coagulation factor concentrates, inhibitors, and other proteins, performed according to standard manufacturing conditions, are shown in Table 3. The kinetics of the virus inactivation in the product intermediates is shown in Fig. 1. Overall, the kinetics were similar for each virus independent of the product intermediate studied.

Table 3.

Virus inactivation by pasteurization under standard conditions (60°C) in stabilized intermediates: (virus RF [log]/Pasteurization Time [hr] for virus infectivity to reach LOD or, in case of residual infectivity, RF after 10‐hour pasteurization time)a

| Virus | FVIIIa | FVIIIb | VWF/FVIII | FIb | F IX/FX | FXIII | PCC | IMIGc | IVIG/IMIGd | A1PI | ATIIIe | ATIIIf | C1‐INH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | ≥6.8/2 | ≥6.1/1 | ≥6.4/2 | ≥5.7/4 | ≥9.8/1 | ≥7.7/4 | ≥5.9/2 | ≥6.5/2 |

≥4.7/0.5 ≥5.5/10c |

≥6.8/2 | ≥7.0/2 | ≥5.0/0.5 | ≥6.6/8 |

| BVDV |

≥6.1/4 ≥9.3/8c |

≥7.1/1 |

≥6.7/4 ≥8.9/6c |

≥9.1/6 | ≥8.9/6 | ≥8.1/6 | ≥8.5/4 |

≥6.4/4 ≥8.7/6c |

≥4.9/1d | ≥5.2/1 |

≥6.6/1 ≥8.0/6c |

≥4.3/1 |

≥5.8/1 ≥9.2/4c |

| PRV | 4.3/10 | ND | 4.7/10 | 6.0/20 | ND | 3.8/10 | 3.8/10 | ≥7.9/6 |

≥3.8/0.5 ≥6.2/10 |

4.4/10 | 6.7/10 | ≥8.9/10e | 6.3/10 |

| HSV‐1 | ≥6.6/4 | ≥7.8/3 | ≥7.0/5 |

≥6.1/1 ≥8.1/4c |

≥6.9/2 | ≥7.6/3 | ≥7.0/4 | ≥6.8/2 | ND | ND | ≥8.1/4 | ND | ≥6.0/2 |

| WNV | ND | ≥7.0/1 | ≥7.8/2 | ≥8.3/4c | ND | ≥7.4/2 | ≥7.4/1 |

≥8.3/2 ≥9.3/6c |

ND | ≥8.3/4 | ≥8.6/0.5 | ND | ≥7.0/0.5 |

| HAV | 3.8/10 | ≥5.8/8c | 4.3/10 | 5.9/20 | 4.1/10 | 4.3/10 | 4.0/10 | ≥5.7/10f | ≥4.0/4g |

≥3.4/6 ≥5.4/10c |

≥5.9/5 | ≥4.6/6g | ≥6.4/5 |

| CPV | 0.7/10 | 1.5/10 | 1.1/10 | 1.4/20 | 1.1/10 | 1.0/10 | 0.5/10 | 2.2/10 | 3.1/10h | 0.9/10 | 1.1/10 | ND | 1.4/10 |

| B19V | ≥3.8/4 | ND | ≥3.9/10 | 4.5/10 | 1.0/10 | ≥4.0/10 | 3.5/10 | ≥5.0/10f | ND | 1.9/10 | 1.0/10 | ND | 3.9/10 |

Therapeutic product: aBeriate; bMonoclate; cBeriglobin; dIntragam; eKybernin; fThromobotrol.

Pasteurization time 20 hours.

Large‐volume testing.

SINV instead of BVDV.

DHBV instead of PRV.

In porcine IgG to avoid neutralization of human pathogenic virus by human IgG.

Encephalomyocarditis virus instead of HAV.

MVM instead of CPV.

A1PI = alpha‐1‐protease inhibitor concentrate; FI = fibrinogen concentrate; IMIG = intramuscular immunoglobulin concentrate; ND = not determined; PCC = prothrombin complex concentrate.

Figure 1.

Pasteurization inactivates a wide range of viruses. Inactivation kinetics of blood‐borne viruses and model viruses by pasteurization (60°C) in different stabilized product intermediates. (A) Inactivation of HIV; (B) inactivation of BVDV; (C) inactivation of PRV; (D) inactivation of HAV; (E) inactivation of CPV; (F) inactivation of B19V. Viruses were spiked in stabilized product intermediate and incubated for 10 hours at 60°C; samples were drawn at different time points to determine the titer of infectious virus. Open symbols indicate no infectivity (virus titer below the LOD of the cell culture infectivity assay). The site of manufacture is identified only in those cases when the same therapeutic protein is produced using different manufacturing processes. ( ) API; (

) API; ( ) ATIII (MBG*); (

) ATIII (MBG*); ( ) C1‐INH (

) C1‐INH ( ) Fibrinogen; (

) Fibrinogen; ( ) FIX / FX; (

) FIX / FX; ( ) FVIIIc (MBG*); (

) FVIIIc (MBG*); ( ) FVIIIc (KAN§); (

) FVIIIc (KAN§); ( ) FXIII; (

) FXIII; ( ) IMIG (MBG*); (

) IMIG (MBG*); ( ) PCC; (

) PCC; ( ) VWF/FVIII; (

) VWF/FVIII; ( ) ATIII (BMW#); (

) ATIII (BMW#); ( ) IVIG/IMIG (BMW#). *Manufacturing facility Marburg, Germany; §manufacturing facility Kankakee, Illinois; #manufacturing facility Broadmeadows, Australia.

) IVIG/IMIG (BMW#). *Manufacturing facility Marburg, Germany; §manufacturing facility Kankakee, Illinois; #manufacturing facility Broadmeadows, Australia.

HIV was inactivated to levels below LOD within 4 hours with RFs of at least 5 log. An exception is the C1 inhibitor concentrate (C1‐INH) intermediate with residual infectivity observed after 4 hours and a RF of at least 6.6 log after 8 hours; the fastest inactivation kinetic for HIV was observed for the product intermediate F IX/FX with RFs of at least 9.8 log within 1 hour. BVDV was inactivated to levels below LOD latest within 6 hours with RFs of at least 6 log. The inactivation kinetic is comparable for all product intermediates.

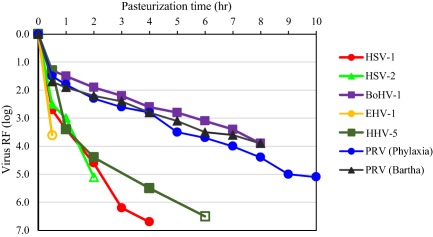

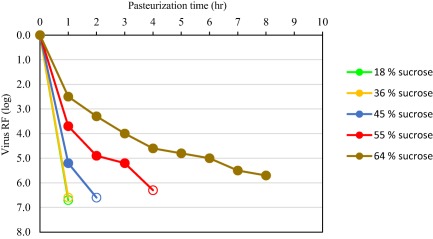

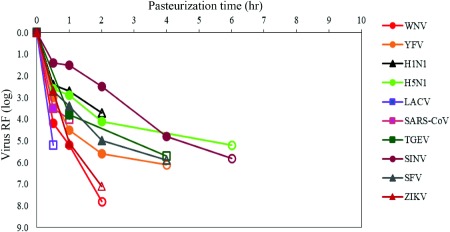

Herpesviruses, employed as nonspecific model viruses, were inactivated effectively by pasteurization. Different herpesviruses, belonging to different herpesvirus genera or species, showed varying inactivation kinetics by pasteurization. The human herpesvirus HSV was rapidly and completely inactivated with RFs of approximately 6 log or more, whereas the porcine herpesvirus PRV (genus Varicellovirus) generally showed partial heat resistance in process intermediates stabilized with sucrose, with virus RFs generally in the order of 4 log. Limited data sets are available for HHV‐5 (genus Cytomegalovirus), the BoHV‐1 (genus Varicellovirus), and EHV‐1 (genus Varicellovirus), pasteurized in a standard stabilizer (sucrose, glycine, and/or potassium acetate, Table 1). A rapid inactivation kinetic was demonstrated for HSV, HHV‐5, and EHV‐1 whereas PRV and BoHV‐1 (belonging to the same genus as PRV) were inactivated at a slower rate (Fig. 2). In contrast to other herpesviruses studied and to all other enveloped viruses studied, the inactivation kinetic of PRV was dependent on the sucrose concentration (Fig. 3). Interestingly, addition of PRV to the stabilized, nonheated product intermediates resulted in a rapid reduction of virus titer by approximately 1.5 log (data not shown). In an in vivo infectivity study using ducklings, DHBV was inactivated below LOD of the duck infectivity assay after 2 hours pasteurization resulting in a virus RF of at least 6.5 log.6 Emerging viruses or respective model viruses were studied in stabilized VWF/FVIII: the flaviviruses WNV, YFV, the influenza viruses H1N1 and H5N1, the bunyavirus LACV, and the coronaviruses SARS‐CoV and TGEV. Effective inactivation of these viruses was demonstrated with no residual infectivity detected by 6 hours (Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Inactivation of herpesviruses. Viruses were spiked in stabilizer solution and incubated for 10 hours at 60°C; samples were drawn at different time points to determine the titer of infectious virus. Open symbols indicate no infectivity (virus titer below the LOD of the cell culture infectivity assay).

Figure 3.

Impact of sucrose concentration on inactivation kinetics of PRV. PRV was spiked in stabilizer solution of increasing sucrose concentration and incubated for 8 hours at 60°C; samples were drawn at different time points to determine the titer of infectious virus. Open symbols indicate no infectivity (virus titer below the LOD of the cell culture infectivity assay).

Figure 4.

Inactivation of emerging viruses and other viruses of potential concern by pasteurization. Emerging viruses and other viruses of potential concern were spiked in stabilizer solution of VWF/FVIII intermediate (as example for stabilized product intermediate of plasma‐derived products) and incubated for 6 hours at 60°C; samples were drawn at different time points to determine the titer of infectious virus. Open symbols indicate no infectivity (virus titer below the LOD of the cell culture infectivity assay) ZIKV from Roth et al. 27

The nonenveloped virus HAV was inactivated by heat treatment reliably and effectively. In about half of all product intermediates evaluated, no residual infectivity was detected at the end of pasteurization with RFs of at least 5.4 log; RFs in other product intermediates ranged from 3.8 to 4.4 log with only low levels of residual infectivity remaining (Tables 3 and 4). The non‐enveloped virus CPV, a heat‐resistant animal parvovirus, was inactivated in the order of 1 log after 10 hours at 60°C whereas the human pathogenic parvovirus B19V was effectively inactivated (approx. 4 log) in product intermediates except antithrombin (ATIII) and API (Table 3).

Table 4.

Virus inactivation by pasteurization under robustness conditions in stabilized intermediates (standard panel of viruses according to CPMP/BWP/268/9514): (virus RF [log]/pasteurization Time [hr] for virus infectivity to reach LOD or, in case of residual infectivity, RF after 10‐hour pasteurization time)

| Producta | HIV | BVDV | PRV | HAV | CPV | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | IS | DT | PS | IS | DT | PS | IS | DT | PS | IS | DT | PS | IS | DT | |

| FVIIIa | ≥6.8/2 hr | ≥6.1/2 hr | ≥6.1/4 hr | ≥5.3/3 hr | ≥6.1/3 hr | 4.3/10 hr | 2.6/10 hr | 3.5/10 hr | 3.8/10 hr | ≥3.4/10 hr | 3.5/10 hr | 0.7/10 hr | ND | ND | |

| FVIIIb | ≥6.1/1 hr | ≥5.6/1 hr | ≥7.1/1 hr | ≥5.0/1 hr | ≥4.9/1 hr | ≥7.8/3 hrb | ND | ≥3.4/3 hrb | ≥5.8/ < 8 hr | ≥5.3/ < 8 hr | ≥5.7/ < 8 hr | 1.5/10 hr | 2.5/10 hr | 1.5/10 hr | |

| VWF/FVIII | ≥6.4/2 hr | ≥5.8/1 hr | ≥6.7/4 hr | ≥5.4/3 hr | ≥5.9/5 hr | 4.7/10 hr | 3.0/10 hr | 3.4/10 hr | 4.2/10 hr | ≥3.4/10 hr | 4.7/10 hr | 1.1/10 hr | 1.3/10 hr | 0.9/10 hr | |

| Fibrinogen | ≥7.5/4 hr | ≥5.8/2 hr | ≥9.1/6 hr | > 5.3/5 hr | > 6.4/5 hr | 4.3/10 hr | ≥3.1/10 hr | 2.4/10 hr | 4.3/10 hr | ≥3.4/10 hr | 2.4/10 hr | 1.2/10 hr | 1.1/10 hr | ND | |

| F IX/FX | ≥9.8/4 hr | ND | ND | ≥6.9/6 hr | ≥6.1/6 hr | ≥6.0/6 hr | ≥6.9/2 hrb | ND | ND | 4.1/10 hr | ≥2.9/10 hr | 3.7/10 hr | 1.1/10 hr | ND | 0.6/10 hr |

| FXIII | ≥7.7/4 hr | ≥4.9/2 hr | ≥6.1/4 hr | ≥6.6/4 hr | ≥5.9/5 hr | 3.8/10 hr | 2.2/10 hr | 2.2/10 hr | 4.3/10 hr | ≥3.4/10 hr | 3.9/10 hr | 1.0/10 hr | ND | ND | |

| PCC | ≥5.9/2 hr | ≥4.5/2 hr | ≥6.4/3 hr | ≥6.3/2 hr | ≥6.4/3 hr | 3.8/10 hr | 2.8/10 hr | 2.2/10 hr | 4.0/10 hr | 4.0/10 hr | 2.8/10 hr | 0.5/10 hr | ND | ND | |

| IMIGc | ≥6.5/2 hr | ≥6.3/2 hr | ≥5.9/2 hr | ≥6.4/4 hr | ≥6.4/4 hr | ≥6.4/4 hr | ≥7.9/2 hr | ≥6.6/2 hr | ≥6.6/4 hr | ND | ND | ND | 2.3/10 hr | 1.8/10 hr | 1.8/10 hr |

| API | ≥6.8/1 hr | ≥5.6/1 hr | ≥5.2/1 hr | ≥4.8/ < 2 hr | ≥5.7/ < 2 hr | 4.4/10 hr | 3.8/10 hr | 3.3/10 hr | ≥5.4/10 hr | ≥4.5/10 hr | ND | 0.9/10 hr | ND | 0.8/10 hr | |

| ATIII | ≥7.0/1 hr | ≥5.5/2 hr | ≥6.6/1 hr | ≥6.6/1 hr | ≥5.8/1 hr | 6.7/10 hr | 6.8/10 hr | 4.6/10 hr | ≥5.9/5 hr | ≥5.1/ < 8 hr | ≥6.8/ < 8 hr | 1.1/10 hr | ND | 0.6/10 hr | |

| C1‐INH | ≥6.6/6 hr | ≥5.1/8 hr | ≥5.8/ < 1 hr | ≥4.8/ < 2 hr | ≥5.7/ < 2 hr | 6.3/10 hr | 5.8/10 hr | 4.4/10 hr | ≥6.4/5 hr | ≥5.1/4 hr | ≥6.4/7 hr | 1.4/10 hr | 0.8/10 hr | 0.8/10 hr | |

Therapeutic product: aBeriate; bMonoclate; cBeriglobin.

HSV‐1 instead of PRV.

DT = decreased temperature (58°C); IS = increased stabilizer concentration (approx. 110%); ND = not determined; PS = production specification.

Reduction factors of robustness studies at increased stabilizer concentrations (105% to 110% after spiking) and at a temperature below production specifications are shown in Table 4. No obvious impacts on the inactivation kinetics or virus RFs were observed for HIV and BVDV. The mean difference in RFs at temperatures at or below product specification for all product intermediates studied was significant for PRV (1.3 log) but nonsignificantly lower for HAV (0.4 log) and CPV (0.3 log). Increased stabilizer concentrations resulted in a nonsignificantly mean lower virus RF for PRV (0.9 log) and HAV (0.6 log). Significance of differences in RFs was assessed in accordance with CPMP/BWP/268/95,14 stating that a RF of 1 log or less is not considered significant.

DISCUSSION

Pasteurization was initially established as an effective virus inactivation method in the production process of human albumin.2, 16 However, the utilization of pasteurization in the manufacturing processes of other therapeutic protein preparations (such as the heat‐sensitive coagulation factors, protease inhibitors, and immunoglobulins) required the addition and optimization of stabilizers to selectively protect the therapeutic protein without simultaneously protecting viruses. The most common stabilizer compositions used within the 14 manufacturing processes were sucrose, sucrose/glycine, or sucrose/potassium acetate combinations, although in some processes sorbitol and citrate were used to protect the therapeutic proteins (Table 1). Under these varying conditions, broad and effective virus inactivation was usually achieved (Table 2).

The critical manufacturing variables for the pasteurization step include temperature, time, and the composition of the product intermediate (including stabilizers and protein composition). These critical variables are tightly controlled, monitored, and verified by quality control practices during the full‐scale commercial manufacturing process and were also similarly controlled during the scale‐down virus validation studies. For each manufacturing process, the robustness of the pasteurization step for virus inactivation was evaluated in two ways: 1) by demonstrating the susceptibility of a diverse variety of enveloped and nonenveloped viruses to the heat treatment procedure and 2) by demonstration of virus reduction under conditions set at or outside the limits of the manufacturing process where virus inactivation kinetics and log reduction could theoretically be impeded (lower temperature and/or higher stabilizer concentration).

The overall results demonstrate that, under the specific conditions optimized for and implemented in each manufacturing process, pasteurization is a highly robust and broadly effective virus inactivation step. Heat inactivation methods such as pasteurization and dry heat treatment thermally destabilize the intermolecular interactions between virus capsid proteins (and/or the integrity of the virus envelope where relevant) thereby resulting in a loss of virion capsid structural integrity and virus infectivity.17 This contrasts to solvent/detergent or caprylate (octanoic acid) inactivation methods that destabilize or destroy the lipid envelope only, not the virus capsid, and are therefore effective for enveloped viruses only.15

Pasteurization effectively (>4 log) inactivated all family members of enveloped viruses studied, evaluated under both target and robustness conditions. All enveloped viruses, except PRV, were inactivated to below the LOD at time points before the 10‐hour production minimum, providing a margin of safety and indicating that the true virus inactivation capacity of the step was likely higher than represented by the log RFs that were demonstrated in the virus validation studies. PRV, a model for herpes viruses and other large DNA enveloped viruses, was also effectively inactivated by pasteurization but with slower inactivation kinetics and the presence of residual infectivity. The slower kinetic rates of PRV inactivation was directly related to sucrose concentration, which illustrates the balance between virus inactivation and protection of therapeutic protein activity; high sucrose concentrations were only employed in processes when required to preserve therapeutic protein functionality. Human herpes viruses studied were inactivated faster than PRV, verifying the use of PRV as a worse‐case model virus in virus validation studies. It should be noted that PRV and herpesviruses are large and, therefore, effectively removed by small‐ (15‐20 nm) and large‐pore (35‐75 nm) virus filtration, partitioned by fractionation steps, and are susceptible to other inactivation steps (e.g., Dichtelmüller et al.18, 19).

Nonenveloped viruses are susceptible to inactivation by pasteurization. HAV was reliably and effectively inactivated by heat treatment in albumin and in stabilized product intermediates, in line with published data.6, 16 However, the HAV strain HM 175, substrain 24a, is reported to have a higher heat sensitivity than other substrains, at least when pasteurized in albumin.20, 21 Studies using the more heat‐resistant HAV substrain 18f demonstrate no or little impact on inactivation kinetics for sucrose stabilized product intermediates (data not shown, manuscript in preparation). Only the nonenveloped animal parvoviruses, CPV and MVM, showed broad resistance to heat treatment (1‐1.5 log), whereas a slightly higher virus RF of up to 3 log was achieved in the presence of immunoglobulins. Interaction between immunoglobulins and the virus may result in destabilization of the virus capsid, similar to that which is described for heat treatment of human parvoviruses.22 In contrast, the human pathogenic parvovirus B19V is effectively inactivated in most product intermediates, consistent with previous data.17, 22 An exception is the ATIII intermediate where high sucrose and CaCl2 concentrations may be the factors that stabilize B19V; this is in line with Boschetti et al.23

Virus reduction steps within biologic manufacturing processes are an important part of the broad and complementary safety measures by serving as a proactive measure against emerging viruses not screened for and which may be asymptomatic in donors. The broad effectiveness of pasteurization against emerging viruses and other viruses of concern has been evaluated in a multitude of virus validation studies that confirm that pasteurized plasma‐derived products can be considered safe regarding these “emerging” viruses. Pasteurization is effective against the flaviviruses WNV and YFV,24 coronaviruses (SARS‐CoV, TGEV), influenzaviruses (H1N1, H5N1), a bunyavirus (LACV), and togaviruses (SINV, SFV) (Fig. 4), which is consistent with published data for TBEV,25 Chikungunya virus,26 and ZIKV.24, 27 Notably, BVDV used as a standard model virus for HCV in virus validation TBEV and YFV studies was demonstrated to be more heat stable than most of the emerging viruses (Fig. 4) and therefore confirms the use of BVDV as a worse‐case model virus for these arboviruses and provides confidence other arthropod‐borne viruses such as, for example, Dengue virus, would also be effectively inactivated.

Inactivation of HEV, a reemerging virus of concern, is currently under evaluation in a wide variety of stabilized product intermediates (to be published separately). Based on data presented or published,28, 29, 30 HEV appears to have similar inactivation kinetics to those of HAV. Pasteurization of HEV in stabilized VWF/FVIII intermediate using an in vivo assay (inoculation of piglets) demonstrated effective inactivation.31

Currently, many complementary safety measures are in place to prevent the transmission of blood‐borne viruses by the administration of commercial plasma‐derived products. These measures include licensed blood and plasma collection centers with appropriate epidemiology regarding HIV, HCV, and HBV in plasma donors,32 mandatory and voluntary testing of all donations for these viruses as well as for HAV and high titers of B19V,33 releasing plasma pools for fractionation for further manufacturing only when nonreactive for virus markers (and not exceeding 104 B19V DNA IU/mL), and the implementation of effective virus reduction steps in the manufacturing process of plasma‐derived products.15 Based on these measures the risk of transmitting blood‐borne viruses via the administration of plasma‐derived products is very remote. As demonstrated by the breadth of studies presented herein, pasteurization is a highly effective virus inactivation step that provides an effective and robust safety measure against both known and emerging enveloped and nonenveloped viruses.

In conclusion, pasteurization is a proven method in inactivating a wide range of enveloped and nonenveloped viruses of different physicochemical properties. Together with appropriate selection of donors, donations and plasma pools, and further manufacturing steps reducing viruses potentially present in the starting material, pasteurized plasma‐derived products have a high safety margin with respect to virus transmission as demonstrated by virus validation studies and confirmed by ongoing hemovigilance.34

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors are employees or former employees of CSL Behring. CSL Behring is a manufacturer of recombinant and plasma‐derived medicinal products.

Supporting information

Table S1. Viruses and cell lines used in pasteurisation studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors give special thanks to current and former laboratory staff within the CSL Behring Pathogen Safety Groups in Australia, Germany, and Switzerland for careful execution of experiments to generate the data described herein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sawyer WA, Meyer KF, Eaton MD, et al. Jaundice in army personnel in the western region of the United States and its relation to vaccination against yellow fever. Am J Hyg 1944;39:337. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gellis SS, Neefe JR, Strokes J, et al. Chemical, clinical, and immunological studies on the products of human plasma fractionation. XXXVI. Inactivation of the virus of homologous serum hepatitis in solutions of normal human serum albumin by means of heat. J Clin Invest 1948;27:239‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Levine PH, McVerry BA, Attock V, et al. Health of the intensively treated haemophiliac, with special reference to abnormal liver chemistries and Splenomegaly. Blood 1977;50:1‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Enck RE, Betts RF, Brown MR, et al. Viral serology (hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein‐Barr virus) and abnormal liver function tests in transfused patients with hereditary hemorrhagic diseases. Transfusion 1979;19:32‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mauler R, Merkle W, Hilfenhaus J. Inactivation of HTLV‐III/LAV, hepatitis B and non‐A/non‐B viruses by pasteurisation in human plasma protein preparations. Develop Biol Stand 1987;67:337‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adcock WL, MacGregor A, Davies JR, et al. Chromatographic removal and heat inactivation of hepatitis B virus during the manufacture of human albumin. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 1998;28:85‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hilfenhaus J, Mauler R, Friis R, et al. Safety of human blood products: inactivation of retroviruses by heat treatment at 60 degrees C. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1985;178:580‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schimpf K, Mannucci PM, Kreutz W, et al. Absence of hepatitis after treatment with pasteurized factor VIII concentrate in patients with hemophilia and no previous transfusions. N Engl J Med 1987;316:918‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schimpf K, Brackmann HH, Kreuz W, et al. Absence of anti‐human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 seroconversion after the treatment of hemophilia A or von Willebrand's disease with pasteurized factor VIII concentrate. N Engl J Med 1989;321:1148‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, et al. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood‐borne non‐A, non‐B viral hepatitis genome. Science 1989;244:359‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barré‐Sinoussi F, Chermann JC, Rey F, et al. Isolation of a T‐lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science 1983;220:868‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gallo RC, Salahuddin SZ, Popovic M, et al. Frequent detection and isolation of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV‐III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science 1984;224:500‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virus validation studies: the design, contribution and interpretation of studies validating the inactivation and removal of viruses. European Commission III/8115/89 . Brussels: European Commission; 1991. Feb.

- 14.Virus validation studies: the design, contribution and interpretation of studies validating the inactivation and removal of viruses. CPMP/BWP/268/95. London: The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, 1996. 14 Feb.

- 15.Guideline on plasma‐derived medicinal products. EMA/CHMP/BWP/706271/2010. London: European Medicines Agency; 2011. Jul 21.

- 16.Guideline on the warning on transmissible agents in summary of product characteristics (SmPCs) and package leaflets for plasma‐derived medicinal products. EMA/CHMP/BWP/360642/2010 rev. 1. London: European Medicines Agency; 2011 Dec 14

- 17. Boschetti N, Niederhauser I, Kempf C, et al. Different susceptibility of B19 virus and mice minute virus to low pH treatment. Transfusion 2004;44:1079‐86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dichtelmüller HO, Biesert L, Fabbrizzi F, et al. Robustness of solvent/detergent treatment of plasma derivatives: a data collection from Plasma Protein Therapeutic Association member companies. Transfusion 2009;49:1931‐43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dichtelmüller HO, Biesert L, Fabbrizzi F, et al. Contribution of safety of immunoglobulin and albumin from virus partitioning and inactivation by cold ethanol fractionation: a data collection from Plasma Protein Therapeutic Association member companies. Transfusion 2011;51:1412‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farcet MR, Kindermann J, Modrof J, et al. Inactivation of hepatitis A variants during heat treatment (pasteurization) of human serum albumin. Transfusion 2012;52:181‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yunoki M, Sakai K, Totsuka A, et al. Hepatitis A virus strain KRM238 resistant at heat inactivation. Transfusion 2013;53:2103‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blümel J, Schmidt I, Willkommen H, et al. Inactivation of parvovirus B19 during pasteurization of human serum albumin. Transfusion 2002;42:1011‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hattori S, Yunoki M, Tsujikawa M, et al. Variability of parvovirus B19 to inactivation by liquid heating in plasma products. Vox Sang 2007;92:121‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blümel J, Musso D, Teitz S, et al. Inactivation and removal of Zika virus during manufacture of plasma‐derived medicinal products. Transfusion 2017;57:790‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nowak T, Gregersen JP, Klockmann U, et al. Virus safety of human immunoglobulins: efficient inactivation of hepatitis C and other human pathogenic viruses by the manufacturing procedure. J Med Virol 1992;36:209‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leydold SM, Farcet MR, Kindermann J, et al. Chikungunya virus and the safety of plasma products. Transfusion 2012;52:2122‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roth NJ, Schäfer W, Popp B, et al. Verification of effective Zika virus reduction by production steps used in the manufacture of plasma‐derived medicinal products. Transfusion 2017;57:720‐1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reflection paper on viral safety of plasma‐derived medicinal products with respect to hepatitis E virus. EMA/CHMP/BWP/723009/2014. London: European Medicines Agency; 2015 Jun 25.

- 29. Yunoki M, Yamamoto S, Tanaka H, et al. Extent of hepatitis E virus elimination is affected by stabilizers present in plasma products and pore size of nanofilters. Vox Sang 2008;95:94‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Farcet MR, Lackner C, Antoine G, et al. Hepatitis E virus and the safety of plasma products: investigations into the reduction capacity of manufacturing processes. Transfusion 2016;56:383‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reflection paper on viral safety of plasma‐derived medicinal products with respect to hepatitis E virus–Appendix: summaries of individual presentations from the EMA Workshop on Viral safety of plasma‐derived medicinal products with respect to Hepatitis E virus, 28‐29 October 2014: HEV Reduction by Selected Manufacturing Steps of CSL Behring's Plasma‐derived Products (Albrecht Gröner, CSL Behring, Germany). EMA/CHMP/BWP/723009/2014. London: European Medicines Agency; 2015 Jun 25.

- 32.Guideline on epidemiological data on blood transmissible infections. EMA/CHMP/BWP/548524/2008. London: European Medicines Agency ; 2016. Feb 25.

- 33. Gröner A. Pathogen safety of Beriate®. Thromb Res 2014;134:S10‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Solomon C, Gröner A, Ye J, et al. Safety of fibrinogen concentrate: analysis of more than 27 years of pharmacovigilance data. Thromb Haemost 2015;113:759‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Viruses and cell lines used in pasteurisation studies.