Summary

Objective To quantify the transmissibility of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in hospitals in mainland China and to assess the effectiveness of control measures.

Methods We report key epidemiological details of three major hospital outbreaks of SARS in mainland China, and estimate the evolution of the effective reproduction number in each of the three hospitals during the course of the outbreaks.

Results The three successive hospital outbreaks infected 41, 99 and 91 people of whom 37%, 60% and 70% were hospital staff. These cases resulted in 33 deaths, five of which occurred in hospital staff. In a multivariate logistic regression, age and whether or not the case was a healthcare worker (HCW) were found to be significant predictors of mortality. The estimated effective reproduction numbers (95% CI) for the three epidemics peaked at 8 (5, 11), 9 (4, 14) and 12 (7, 17). In all three hospitals the epidemics were rapidly controlled, bringing the reproduction number below one within 25, 10 and 5 days respectively.

Conclusions This work shows that in three major hospital epidemics in Beijing and Tianjin substantially higher rates of transmission were initially observed than those seen in the community. In all three cases the hospital epidemics were rapidly brought under control, with the time to successful control becoming shorter in each successive outbreak.

Keywords: SARS, transmission, hospital, China

Introduction

During the 2003 epidemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐CoV) was a predominately hospital‐acquired pathogen in Canada, Singapore and Vietnam, where between 40% and 57% of cases occurred among healthcare workers (HCWs) (Booth et al. 2003; Ofner‐Agostini et al. 2006). In contrast, in mainland China most documented SARS transmission occurred in the community (Feng et al. 2009). Nonetheless, significant nosocomial transmission did occur, and healthcare workers (HCWs) were the largest single group of workers affected, accounting for 19.2% of all reported cases (Feng et al. 2009). While in some hospitals clinical features and therapeutic approaches have been documented (Wu et al. 2003; Zou et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2006), and previous modelling studies have estimated the importance of different transmission routes in hospital settings (Kwok et al. 2007), there have been no attempts to quantify the time‐evolution of SARS transmissibility in hospital settings in mainland China.

A key quantity in tracking the course of an epidemic is the effective or net reproduction number (R t), which measures the mean number of secondary cases caused by a typical infected case. This number will change during the course of an epidemic as a result of changing control measures and declining numbers of susceptibles (and perhaps also environmental factors). A necessary condition for a major epidemic to occur is that this number is initially greater than the threshold value of one, enabling a sustained chain of transmission to occur. A sufficient condition for successful control of an epidemic (indeed, a practical definition of control) is that this number is maintained below one. If this happens, though continued transmission may occur, it will be at a level too low to permit the self‐sustaining chain reaction that constitutes an epidemic, and eventual fade‐out is assured. By tracking the value of R t over time it is possible to quantify the degree of ongoing transmission and to see how far from successful control an epidemic is at a given time point (Wallinga & Teunis 2004).

The aims of this paper are to report three of the main clusters of nosocomial transmission of SARS in mainland China and the control measures taken, and to estimate the evolution of the effective reproduction number in each of the three hospitals during the course of these outbreaks. These estimates allow us to quantify the effort required to control the epidemics and help to determine to what extent different control measures, such as vaccination or isolation, will be effective at preventing or controlling future outbreaks.

Materials and methods

Settings

The three hospitals affected are referred to as hospital A, B and C throughout this paper. During the period of the SARS epidemic in 2003, hospital A, a general hospital in Beijing, had 1700 beds within a 14‐floor in‐patient building. It had approximately 3600 HCWs, 80 000 in‐patient visits and 2.5 million out‐patient visits per year. The main departments affected by SARS were the department of liver and gall surgery, and the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery.

Hospital B refers to a general hospital in Beijing, which at the time of the epidemic had 450 beds within a five‐floor in‐patient building. Departments principally affected by SARS were the respiration department on floor three, the Department of Digestive Diseases, the Department of Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Hospital C refers to a general hospital in Tianjin that had 400‐beds within a six‐floor in‐patient building and 669 HCWs (169 doctors, 230 nurses, 17 medical technicians, 23 apothecaries, 34 management staff, 142 logistic service staff and 54 house service staff). The main departments affected by SARS were the cardiovascular department on floor three (which includes a critical care unit and intervention therapy room), a second cardiovascular department, and the house service department.

Data collection

Data collected for probable SARS cases included name, gender, age, occupation, date of onset, place or department of onset, date of confirmation of the diagnosis, and date of death or recovery. Information about probable contact history was collected in a retrospective investigation that aimed to establish possible transmission chains. Probable SARS cases were defined according to the criteria of World Health Organization (2003) guidelines on case definitions. Only confirmed (probable) cases are reported in this paper. No details on the number of susceptible cases or uninfected staff or patients were available from any of the three hospitals.

Analysis

The evolution of the effective reproduction number during the epidemics in each of the three hospitals was estimated using the method described by Wallinga and Teunis (2004), using a generation interval given by a Weibull distribution with a shape parameter of 2.22 and scale parameter of 8.95, as estimated by Lipsitch et al. (2003). Transmission in the community resulting from cases with onset outside the hospital was not considered in the analysis. For the purpose of the analysis, for those with onset outside the hospital, the onset time was taken as the admission time. It was necessary to modify the method slightly for the analysis of hospital A data, where several cases believed to be infected by contact with patients in hospital A were visiting relatives in hospital and were admitted to another hospital on developing symptoms. In the analysis, these cases were assumed to have been infected by cases within hospital A, but not to pose any risk of transmission to other patients within hospital A. Mortality data were analysed using a logistic regression model.

Results

Description of the three hospital epidemics

The index case, a 27‐year‐old businesswoman, was admitted to the Department of Respiration on floor seven of hospital A on 3 March 2003. On the same day, doctors in the Department of Respiration suspected that she was suffering from SARS on the basis of her symptoms (which had started on 21st February) and her history of traveling. Isolation measures were put in place and health education and disinfection measures were taken. On 5th March she was transferred to an infectious disease hospital.

On the same day (5th March) the mother and father of the index case were admitted to the same infectious disease hospital, followed by a friend on 7th March, and then her husband, brother, two brothers‐in‐law, son, sister‐in‐law, and two friends on 8th March. All were confirmed as probable SARS cases, and all apart from the parents of the index case survived.

Subsequently, on 8th March, onset of SARS occurred in a 58‐year‐old man who had been admitted to the department of liver and gall surgery on floor eight on the same day as the index case. It was thought likely that this patient had become infected either through sharing an elevator with the index case or via a ventilation duct. A further in‐patient in the same ward and two nurses and two doctors who had taken care of this patient and a HCW in the same department who had indirect contact with the patient subsequently become infected. It was thought likely that the outbreak subsequently spread to floors 13 and 14 via the ventilation duct, which was shared with wards on floor eight.

A second chain of transmission in hospital A could be traced to another apparent index case: a 73‐year‐old retired man who developed symptoms on 1 March 2003 and was admitted on 4th March to the Department of Oral Cavity. One patient (on the same ward as this index case), his wife and his son, and one member of hospital staff (a driver working for the transportation service) who had had direct contact with this patient were subsequently confirmed as probable SARS cases.

On 16 March, the first fever clinic in Beijing was established for screening out‐patients with fever at hospital A. At the same time areas for quarantine and hospital isolation wards were set up in the hospital and other improved infection prevention measures for healthcare workers were instigated.

The epidemic in hospital B started with the introduction of two index cases. The first was a male 39‐year‐old taxi driver admitted to Department of Respiration on 25 March 2003 with fever (38.6 °C), cough, muscle pain and arthritis. When admitted he had already been ill for 6 days, and was diagnosed as a suspected SARS case and later confirmed as a probable case. The second index case was a 31‐year‐old female admitted to the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics on 26th March, after being transferred from another hospital. Both patients were subsequently transferred to other hospitals, the first leaving 2 days later on 27th March and the second leaving 8th April. In both cases, SARS was only confirmed on leaving hospital B.

The first secondary cases in hospital B occurred on 29th March when two nurses who had treated the first index case in the Department of Respiration developed symptoms. Five more HCWs and one patient who were documented as having had direct contact with the first index case went on to become confirmed SARS cases, and 17 HCWs and 17 patients who were documented as having had indirect contact subsequently became confirmed SARS cases. The six cases with onset of symptoms between 29th and 31st March (three nurses, two doctors and one in‐patient) prompted the hospital administration to immediately take the following measures on April 1st:

-

•

The hospital was closed to new patients and everyone in the hospital, including staff, was forbidden to leave.

-

•

Disposable monolayer masks were dispensed to all staff and patients.

-

•

All suspected SARS cases were cohorted in one area of the hospital (strict isolation measures, however, were not put in place at this point).

New SARS cases continued to appear following this intervention (Figure 1). A team of microbiologists and epidemiologists visited the hospital on 4th April, and advised on control measures and recommended transferring SARS patients to other sites. From this point onwards, isolation and disinfection measures were taken in the hospital wards, and on 5th April isolation facilities outside the hospital were prepared for patients with SARS. These facilities contained an isolation zone, a half‐contaminated area, and a clean area with a buffer zone between them. Sixteen‐layer masks (not N95 masks, as strict protection measures had not been introduced at that time) and strict disinfection measures were taken in these isolation facilities. The first group of SARS cases (composed mostly of infected senior staff) was moved to these isolation facilities on 8th April. On 10th April, the second group, composed mostly of junior staff suspected of having SARS, were moved to the isolation facilities. Uninfected staff were commanded to remain in the hospital for quarantine. On 12th April (the onset date of the last SARS patient in hospital B), the third group, composed mostly of in‐patients suspected of having SARS, was transferred to the isolation sites. Other uninfected staff remained in hospital B for quarantine. On 25th April, all measures were taken in accordance with the SARS prevention and control protocol issued by the Chinese ministry of health.

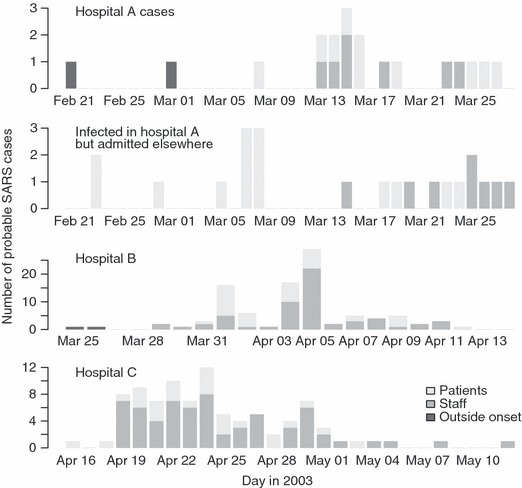

Figure 1.

Epidemic curves for hospitals A, B and C. The top panel shows cases who were admitted to hospital A. The first two of these were believed to have been index cases who were infected from sources outside hospital A. The panel below this shows cases believed to have been infected in hospital A, but who, on developing symptoms, were admitted to other hospitals. These people include both staff at hospital A (dark grey bars) and visitors to hospital A patients (light grey bars). Cases infected in hospitals B and C (bottom two panels), in contrast, were treated in the same hospital.

The epidemic in hospital C started on 15 April 2003, when the index patient, a 54‐year‐old male with coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure was transferred to the Cardiovascular Department Unit I (floor three in the in‐patient building) from a general hospital in Beijing. The next morning he was diagnosed as a suspected SARS patient and transferred to Tianjin lung hospital and subsequently Tianjin Lazaretto where the diagnosis of SARS was made. He died on 18 April 2003. During the therapy and transfer procedure in hospital C, no specific respiratory isolation precautions had been used and a major SARS outbreak resulted, with 91 probable and 20 suspected SARS cases. On 24th April hospital C was closed to admissions, no‐one was permitted to leave and a three‐level isolation strategy was implemented with staff and patients allocated to different areas according to their risk of having SARS (the high risk area being further subdivided according to whether cases were probable or suspected). Each area had specific rules for the use of personal protective equipment with the high risk area mandating use of gloves, masks, gowns and protective eyewear at all times. Further details of this epidemic and the control measures taken have been reported elsewhere (Wang et al. 2006; Wei et al. 2009).

Mortality

Mortality rates were similar across all three hospitals (Table 1), and univariate analysis of the mortality data showed that only age and whether or not a person was a healthcare worker were significantly associated with mortality (which was higher in the elderly, and lower in HCWs). After adjustment for all covariates both remained significant predictors of mortality (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the SARS epidemic in three Chinese hospitals

| Hospital A | Hospital B | Hospital C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date of onset of first case | 21/2/2003 | 25/3/2003 | 16/4/2003 |

| Date of onset of last case | 28/3/2003 | 12/4/2003 | 12/5/2003 |

| Total cases | 41 | 99 | 91 |

| Onset outside hospital (%) | 2 (5) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Mean age (SD) | 40.8 (19.4) | 33. 6 (14.8) | 39.0 (16.4) |

| Female (%) | 16 (39) | 57 (58) | 55 (60) |

| Mortality (%) | 8 (20) | 10 (10) | 15 (16) |

| Hospital staff cases (%) | 15 (37) | 59 (60) | 64 (70) |

| Mean age (SD) | 33.7 (15.9) | 30.3 (9.0) | 33.3 (12.1) |

| Female (% of staff cases) | 10 (67) | 45 (76) | 48 (86) |

| Mortality (% of staff cases) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 3 (5) |

| Patient cases (%) | 26 (63) | 40 (40) | 27 (30) |

| Mean age (SD) | 44.7 (20.4) | 38.2 (20.4) | 52.5 (17.5) |

| Female (% of patient cases) | 6 (23) | 12 (30) | 7 (26) |

| Mortality (% of patient cases) | 8 (31) | 8 (20) | 12 (44) |

Table 2.

Results of logistic regression analysis of SARS mortality data

| Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.12 (1.08, 1.16) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.06, 1.14) | <0.001 |

| Male | 3.18 (1.46, 6.94) | 0.004 | 1.57 (0.54, 4.56) | 0.41 |

| HCW | 0.09 (0.03, 0.23) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.08, 0.87) | 0.03 |

| Hospital A | 1.64 (0.68, 3.96) | 0.27 | 1 (baseline) | |

| Hospital B | 0.53 (0.24, 1.18) | 0.12 | 1.00 (0.24, 4.07) | 1.00 |

| Hospital C | 1.32 (0.63, 2.77) | 0.47 | 1.08 (0.29, 4.11) | 0.91 |

Rt estimation

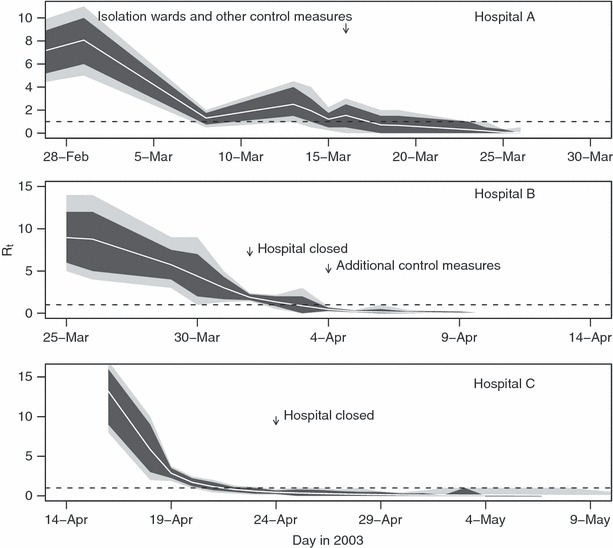

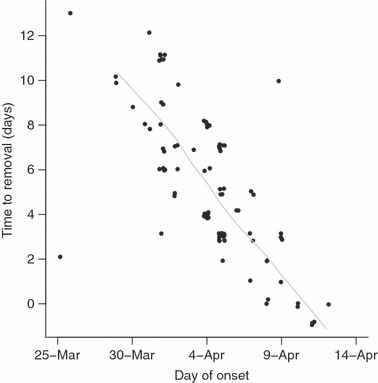

The estimated evolution of the net reproduction number (R t) in the three main clusters of transmission (Figure 2) showed substantial between‐hospital variation, though also some commonalities. In hospital A the estimated reproduction increased over the first few days of the epidemic, but values then rapidly declined and the epidemic was under control (R t < 1) within 25 days from the onset of the first case in hospital A. In contrast, initial rates of transmission were slightly higher in hospitals B and C, but then declined monotonically, leading to rapid control of the epidemics. This occurred within 10 days of the first case in hospital B, and within about 5 days in hospital C. In hospital B the time from onset to removal and isolation showed a sharp linear decline from 30th March (Figure 3) and this was associated with the decline in the R t values. Comparable data were not available from the other two hospitals.

Figure 2.

Estimated effective reproduction number (R t) during the transmission chain in the three hospitals (central white line) and associated 95% (grey) and 80% (black) confidence intervals. The critical value of one, below which sustained transmission is impossible, is marked with a broken horizontal line. Transmission in the community resulting from cases prior to hospitalization is not considered in these estimates.

Figure 3.

Delay from onset of symptoms to removal (discharge or transfer to isolation facility at another hospital) from hospital B. Times are recorded only to the nearest day, but a small amount of random noise (jitter) has been added to the points to enable visualization of overlapping data points. A lowess (locally weighted regression) smoothing line is also plotted.

Discussion

There was some evidence of differences in the epidemic characteristics between the three hospitals in this study: only 37% of the probable cases in hospital A were amongst HCWs, which was lower than corresponding figures for hospital B (60%) and hospital C (70%). Only these latter two hospital outbreaks therefore resembled the epidemic pattern seen in Singapore, Canada, and Vietnam, where 40–60% of cases occurred amongst healthcare workers (Booth et al. 2003; Dwosh et al. 2003; Varia et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2006; Ofner‐Agostini et al. 2006; Feng et al. 2009). However, there were only 41 cases in hospital A and differences in the proportion of HCWs affected are fully consistent with those expected due to chance effects alone.

One limitation of the approach used to estimate the time evolution of the reproduction number is that when case numbers are low, estimates may be dominated by rare ‘superspreading’ events. Such events have featured in SARS transmission in Singapore (Lipsitch et al. 2003), Hong Kong (Riley et al. 2003), Canada (Poutanen et al. 2003) and could potentially explain the initial unusually high reproduction number found in hospital C. The hypothesis of such a superspreading event is supported by the fact that 15 of the secondary cases in hospital C were HCWs who had previously treated the index patient, while five other cases were present on the same ward.

Analysis of the three hospital outbreaks has shown that epidemics were brought under control faster with each new epidemic, with the most rapid control in hospital C and the least rapid control in hospital A. However, the lack of information on the number of susceptibles makes assessing the importance of specific control measures for reducing transmission impossible: once the hospitals were closed to new admissions, a decline in the effective reproduction number would be expected as the supply of susceptibles diminishes during the course of the epidemic. Without knowledge of the number of susceptible staff and patients the relative importance of this mechanism compared to other control measures for the control of SARS transmission cannot be assessed.

Nonetheless, we can speculate on the importance of control measures. It seems plausible that the increasingly rapid isolation of cases was partly responsible for the sharp reduction in the effective reproduction number in hospitals B and C. Unfortunately with available data it is only possible to confirm this trend for increasingly rapid isolation in hospital B (Figure 3). While the change in R t in hospital C showed a similar pattern to that in hospital B, the initial value of R t was somewhat higher and the time to successful control was shorter. Possible reasons for the more rapid control in hospital C include the fact that the outbreak in hospital C occurred some days after the hospital B outbreak, and patients may therefore have been isolated faster or more effectively as a result of the experience gained from the earlier outbreak. However, lack of data from hospital C regarding isolation times makes this impossible to establish. In hospital A, the progressive reductions in the net reproduction number (R t) are most likely to have resulted from the early isolation measures, health education, disinfection measures and transfer of SARS patients to an infectious diseases hospital. However, high‐risk exposures caused by visitors to the hospital who were infected with SARS‐CoV could have caused the observed increase in the estimated reproduction number over the first few days of the epidemic.

The most striking finding was that estimated R t values early in the hospital epidemics were considerably higher than those seen in the community or population‐averaged values (Cowling et al. 2008). Maximal values were between 10 and 15 compared to maximum values for Beijing as a whole of only three or four. This provides confirmation of the view that hospitals have the potential to amplify transmission (Lloyd‐Smith et al. 2003). This probably reflects the high frequency of close contacts seen in hospital environments, and similar findings might be expected in other closed communities such as schools or military barracks. The results also suggest that the requirements for control would be considerably more stringent for a hospital population compared to the wider community. For example, a higher proportion of the population would need to be vaccinated to prevent an outbreak, or the effectiveness of isolation measures would need to be greater to guarantee control. Fortunately, the fact that all (or almost all) SARS transmission appears to be from symptomatic individuals means that even with reproduction numbers as high as those observed here isolation of cases is likely to be able to control outbreaks provided isolation measures are close to fully effective (Fraser et al. 2004). In contrast, the lower transmission potential in the community means that even isolation measures that only about 75% effective at preventing transmission would suffice to control an outbreak. Such imperfect isolation would not be able to control outbreaks for the highest reproduction numbers seen in these hospital settings.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Commission of the European Community under the Sixth Framework Program Specific Targeted Research Project, SARS Control “Effective and Acceptable Strategies for the Control of SARS and new emerging infections in China and Europe” (Contract No. SP22‐CT‐2004‐003824), and Grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China for Excellent Young Scientists (No. 30725032), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30590374).

References

- Booth CM, Matukas LM, Tomlinson GA et al. (2003) Clinical features and short‐term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. The Journal of the American Medical Association 289, 2801–2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MI, Leo YS, Ang BS, Heng BH & Choo P (2006) The outbreak of SARS at Tan Tock Seng Hospital–relating epidemiology to control. The Annals, Academy of Medicine, Singapore 35, 317–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling BJ, Ho LM & Leung GM (2008) Effectiveness of control measures during the SARS epidemic in Beijing: a comparison of the R t curve and the epidemic curve. Epidemiology & Infection 136, 562–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwosh HA, Hong HH, Austgarden D, Herman S & Schabas R (2003) Identification and containment of an outbreak of SARS in a community hospital. Canadian Medical Association Journal 168, 1415–1420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D, De Vlas SJ, Fang LQ et al. (2009) The SARS epidemic in mainland China: bringing together all epidemiological data. Tropical Medicine and International Health 14 (Suppl. 1), 4–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser C, Riley S, Anderson RM & Ferguson NM (2004) Factors that make an infectious disease outbreak controllable. Proceedings of the Natlional Academy of Sciences USA 101, 6146–6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok KO, Leung GM, Lam WY & Riley S (2007) Using models to identify routes of nosocomial infection: a large hospital outbreak of SARS in Hong Kong. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Series B 274, 611–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitch M, Cohen T, Cooper B et al. (2003) Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 300, 1966–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd‐Smith JO, Galvani AP & Getz WM (2003) Curtailing transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome within a community and its hospital. Proceedings Biological Sciences/The Royal Society 270, 1979–1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofner‐Agostini M, Gravel D, McDonald LC et al. (2006) Cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome among Toronto healthcare workers after implementation of infection control precautions: a case series. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 27, 473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutanen SM, Low DE, Henry B et al. (2003) Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. New England Journal of Medicine 348, 1995–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley S, Fraser C, Donnelly CA et al. (2003) Transmission dynamics of the etiological agent of SARS in Hong Kong: impact of public health interventions. Science 300, 1961–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varia M, Wilson S, Sarwal S et al. (2003) Investigation of a nosocomial outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Toronto, Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal 169, 285–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallinga J & Teunis P (2004) Different epidemic curves for severe acute respiratory syndrome reveal similar impacts of control measures. American Journal of Epidemiology 160, 509–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SX, Li YM, Sun BC et al. (2006) The SARS outbreak in a general hospital in Tianjin, China – the case of super‐spreader. Epidemiology and Infection 134, 786–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei MT, De Vlas SJ, Yang Z et al. (2009) The SARS outbreak in a general hospital in Tianjin, clinical aspects and risk factors for diseases outcome. Tropical Medicine and International Health 14 (Suppl. 1), 60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2003) Case Definitions for Surveillance of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Wang J, Liu P et al. (2003) A hospital outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Guangzhou, China. Chinese Medical Journal (Engl) 116, 811–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Q, Lin WS, Du L et al. (2004) An investigation on nosocomial infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome in health‐care workers at 13 key hospitals in Guangdong Province. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 38, 87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]