Plenary

Plenary Oral Abstract Session

P1‐MN1‐6

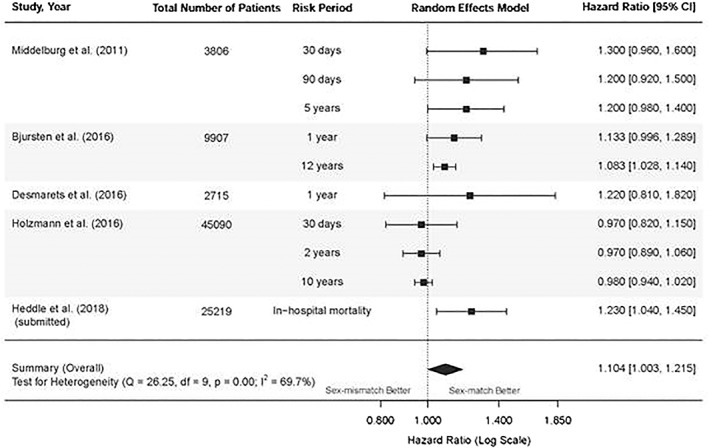

No Effect of Blood Donor Sex and Pregnancy History on the Survival of Transfused Patients: A Joint Analysis of Three Retrospective Cohorts

Gustaf Edgren1,2, Edward Murphy3,4, Donald Brambilla5, Henrik Ullum6, Catherine Lee7, Matt Westlake5, Steve Kleinman8, Darrell Triulzi9, Ritchard G. Cable10, Elizabeth St. Lezin4,11, Roberta Bruhn3, Henrik Hjalgrim6,12, Simone Glynn13 and Nareg Roubinian*3,4,7

1Karolinska Institutet, 2Södersjukhuset, 3Blood Systems Research Institute, 4University of California, 5RTI International, 6Rigshospitalet, 7Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, 8University of British Columbia, 9The Institute for Transfusion Medicine, 10American Red Cross, 11San Francisco Veterans Affairs HCS, 12Statens Serum Institut, 13National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute

Background/Case Studies: A recent publication reported that red cell transfusions from previously pregnant female donors markedly increased the mortality of transfused male patients. The findings would—if true—have far‐reaching clinical and administrative implications in the management of the blood supply. However, these results may have been influenced by biases introduced in the statistical analysis.

Study Design/Method: We separately analyzed data from three linked blood donor and recipient cohorts including data from the US and Scandinavia, over long time periods. Patients were followed from the time of first red cell transfusion for the occurrence of both in‐hospital and long‐term mortality. We used separate Cox regression models to estimate the associations between number of red cell transfusions from a female donor, a previously pregnant donor, and a donor sex‐discordant with the recipient—all treated as time‐dependent—and risk of death while controlling for total number of red cell transfusions received using a stratified Cox model. Analyses were performed for overall effect and stratified by recipient sex and age.

Results/Finding: We included a total of 53,890 patients (5,654 deaths), 93,724 patients (8,519 deaths) and 918,996 patients (198,537 deaths with longer follow up) in cohorts I, II and III, respectively. There was no association between any of the donor characteristics and in‐hospital mortality in any of the three cohorts (Table). Hazard ratios per transfused unit from a parous female donor were all non‐significant, ranging from 0.99 to 1.02. Results were similar for the effect of donor sex and sex‐discordance on in‐hospital mortality (Table), as well as with long‐term mortality in two of the cohorts (data not shown). Effect estimates did not differ with recipient sex, and/or age. Categorical analyses did not show negative effects in heavily exposed patients.

Conclusion: In this joint analysis of data from three large cohorts of transfused patients, we found no evidence of an association between donor sex, or parity and either in‐hospital or long‐term patient survival. These null findings using a similar statistical approach across more than a million patients from heterogeneous clinical settings in different countries indicate that prior findings seem unlikely to reflect true biological effects.

(P1‐MN1‐6) Risk of in‐hospital death, in relation to transfusion exposures, for the three cohorts.

| Hazard ratio per unit (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort I | Cohort II | Cohort III | |

| Number of transfusions from female donors | 0.99 (0.96‐1.03) | 1.00 (0.99‐1.01) | 1.00 (0.99‐1.00) |

| Number of transfusions from parous female donors | 1.00 (0.96‐1.05) | 1.01 (1.00‐1.02) | 1.00 (1.00‐1.01) |

| Number of sex‐discordant transfusions | 1.02 (0.99‐1.05) | 0.99 (0.98‐1.00) | 1.00 (1.00‐1.00) |

P2‐MN1‐6

Cryopreserved Platelets for Surgical Bleeding: Protocol for the CLIP‐II Trial Based on CLIP‐I Pilot Data

Michael Reade*1,2, Denese C. Marks3, Zoe K. McQuilten4, Lacey Johnson3 and Erica M. Wood4

1Joint Health Command, Australian Defence Force, 2Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, 3Research and Development, Australian Red Cross Blood Service, 4Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University

Background/Case Studies: Platelets are essential for optimal haemostasis and to preserve the endothelial glycocalyx in resuscitation from shock. However, the 5‐7 day shelf‐life of conventional room‐temperature stored platelets means they are usually not available outside large hospitals. Cryopreservation at ‐80C in dimethylsuphoxide extends shelf‐life to 2‐4 years, with reconstitution in plasma requiring minimal time, specialised equipment or training. However, despite encouraging preclinical and phase I data, only one phase II trial, in which only 24 patients received cryopreserved platelets, has been published. The CLIP trial program is seeking to provide sufficient phase III trial data for regulatory approval.

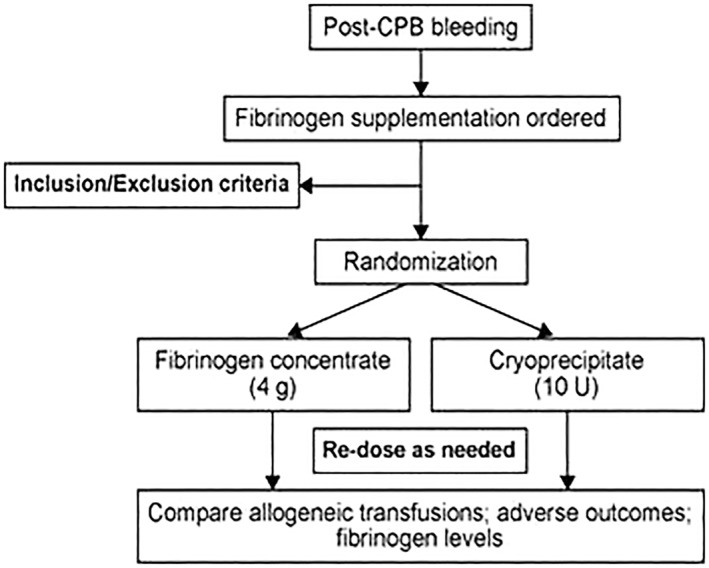

Study Design/Method: Between July 2015 and December 2017 in 4 hospitals, we enrolled cardiac surgical patients at particularly high risk of perioperative bleeding (identified using the TRUST criteria (Alghamdi et al., Transfusion, 2006)) in the CLIP‐I pilot trial (ACTRN12612001261808). Patients were randomised 1:1 to receive either cryopreserved or liquid‐stored platelets if their treating clinicians decided a platelet transfusion was indicated. Cryopreserved platelets were prepared by the Australian Red Cross Blood Service using a method based on that of the Netherlands Military Blood Bank, a modification of the original protocol described by the US Navy.

Results/Finding: In total, 121 patients were randomised, of whom 42 (35%) received a platelet transfusion. Study groups were well‐matched at baseline. There were no significant differences in any effectiveness outcome, but there was a trend for the cryopreserved group to require fewer red blood cell units transfused (median [IQR] 2.5 [1‐5] vs. 4 [3‐5] units, p=0.18). There was a trend towards the cryopreserved group having less blood in their chest drains at 24hr (median [IQR] 712 [540‐825] vs. 805 [591‐1080]ml, p=0.27). For the composite outcome defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC), there was a trend to superiority in the cryopreserved platelet group (27.3% vs. 55.6%, p=0.07). There were no clinically important differences in any measured adverse events.

Conclusion: In this pilot trial, cryopreserved platelets were associated with no evidence of harm and small non‐significant trends to reduced requirement for red cell transfusion and reduced postoperative blood loss. In the light of this data and the clear logistic advantages of cryopreservation, a definitive study with a non‐inferiority design testing volume of postoperative bleeding as the primary outcome is warranted. Improved identification of patients at high risk for a platelet transfusion using a platelet‐specific transfusion risk prediction score will increase the efficiency of the phase III trial.

P3‐MN1‐6

Infectious Disease (ID) Rates Among Donors Reinstated After Changes to the Men Who Have Sex with Other Men (MSM) Deferral Policy

Yvette M. Miller1, Kathleen M. Grima1, Artan Apostoli1, Julie Hall1, Ed P. Notari1, Roger Y. Dodd2 and Susan L. Stramer*1

1American Red Cross, 2American Red Cross Holland Laboratory

Background/Case Studies: Changes to the deferral policy for MSM were FDA approved in Dec 2015. These allowed previously deferred donors having reported MSM “ever” to donate if no activity was reported in the prior 12 months and all other eligibility criteria were met. New donor eligibility policies were implemented in phases by the American Red Cross beginning in Dec 2016. We reviewed the infectious disease (ID) history and number of donors with a prior MSM history who now qualified and donated; these were compared to the general donor population.

Study Design/Method: Queries were developed to identify indefinitely deferred MSM donors otherwise eligible for blood donation. Once identified as eligible, the computer‐generated MSM deferral was removed. The queries covered deferrals from Jan 2010‐Jan 2018; all reinstatements occurred from Dec 2016‐Jan 2018. An additional query was developed to track any subsequent donations/deferrals for any reinstated donor. Eligibility was communicated, assuming all criteria remained acceptable including absence of MSM in the prior year, following telephone calls to a toll‐free number; reinstated donors were also recruited for donation based on current eligibility. All reinstated donors were required to meet the same donor requirements as any other donor. Rates of ID markers in reinstated donors were compared by chi‐square testing to the general donor population, both donating during 2017.

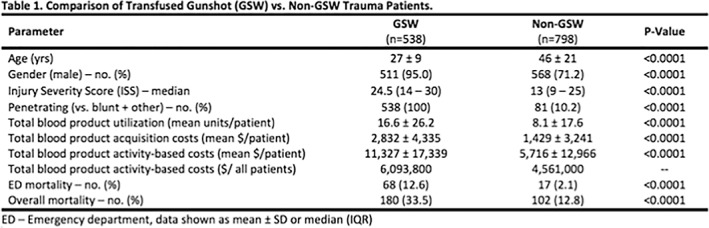

Results/Finding: 520/22,482 (2.3%) donors returned to donate after their indefinite MSM deferral was removed; 7 donors had ID deferrals following reinstatement (2 confirmed syphilis, 5 anti‐HBc‐reactive on 2 occasions of which 3 had a 1x history prior to reinstatement and 2 had both anti‐HBc reactives post reinstatement; of note, 1 anti‐HBc reactive donor was also an incident HIV NAT converter). An additional 72 donors returned to donate after a subsequent 12‐month MSM deferral of which 2/72 had ID deferrals following reinstatement; both had confirmed syphilis and one donor was also HIV (antibody+NAT) positive with acknowledged ongoing MSM. The overall rate for all ID markers for routine donors in 2017 was 0.4% (21,676/4,829,679) as compared to 1.3% (7/520) in reinstated indefinitely deferred MSM donors (p<0.01; Odds Ratio, OR 3.0; 95% Confidence Interval, CI 1.44‐6.38), or 2.8% (2/72) in reinstated 12‐mo deferred MSM donors (p<0.05; OR 6.3; 95% CI 1.55‐25.84).

Conclusion: Federally funded programs investigating variation in HBV, HCV and HIV prevalence and incidence have not yet detected significant changes, indicating comparable safety pre‐ and post‐MSM policy change. However, review of MSM reinstated donors for all ID‐markers versus general donors shows trends that require careful monitoring.

P4‐MN1‐6

Incidence of Red Blood Cell Alloimmunization and the Impact of Prophylactic Antigen Matching in Patients with Warm Autoantibodies

Meghan Delaney*1, Torunn Oveland Apelseth2, Carolina Bonet Bub3, Claudia S. Cohn4, Nancy M. Dunbar5, Jose M. Kutner6, Michael Murphy7, Kathleen Selleng8, Julie Staves9, Silvano Wendel10 and Alyssa Ziman11

1Children's National Health System, 2Department of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, 3Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, 4University of Minnesota, 5Dartmouth‐Hitchcock Medical Center, 6Einstein Medical Center, 7John Radcliffe Hospital, 8Institute for Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, University Medicine Greifswald, 9Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 10Hospital Sirio Libanes Blood Bank, 11Division of Transfusion Medicine, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

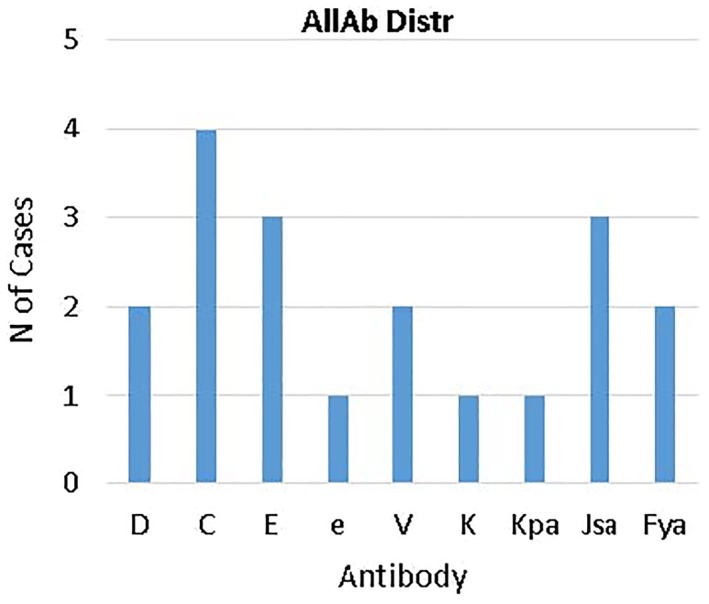

Background/Case Studies: Warm autoantibodies (WAA) are panreactive autoantibodies that complicate compatibility testing and can cause clinical hemolysis. The rate of patients with WAA developing red blood cell (RBC) alloimmunization is not well understood; single center studies cite rates of 8 – 39% of patients. Substantial laboratory resources are used for evaluation and RBC selection; however, there is no evidence‐based or uniform approach for these activities. The goal of this study is to understand the prevalence of WAA and risk of RBC alloimmunization in this population, and whether RBC selection practice had an impact on alloimmunization.

Study Design/Method: Records of patients (>1 year of age) with an antibody detection test (IAT) and evidence of WAA were included. To determine the incidence of RBC alloimmunization in patients with WAA, patients that received RBC transfusion and had an IAT ≥30 days later were reviewed. To determine the impact of RBC product selection approach, patients were subdivided into those that received prophylactically antigen matched (PAM) RBCs for transfusion and those that did not.

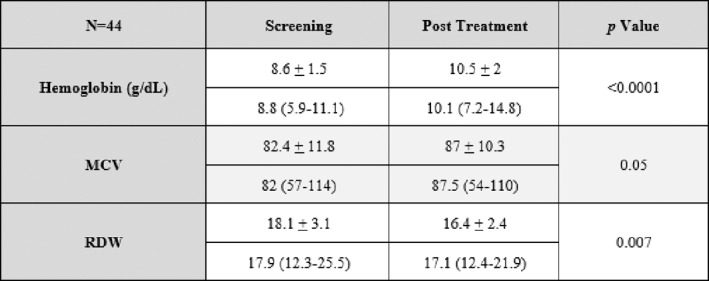

Results/Finding: Eight centers from 5 countries collectively reviewed 1,122,245 patients who had an IAT. In the patients tested at transfusion services laboratories (TSL), 1,218 had a WAA (0.17%, range 0.01‐0.36%). One center combined TSL and immunohematology reference laboratory (IRL) had 3990 patients with WAA (1.03%). The range of prevalence of WAA detection at TSL centers was 0.01 to 0.36%. Of TSL patients with WAA, 410 (33.7%) had evidence of RBC alloimmunization either prior to or at the time of WAA identification, while 808 patients (66.3%) had only WAA detected. 843 (69.2%) patients with WAA were transfused and 431 (35.4%) did not receive a RBC transfusion after detection of WAA. Of patients with WAA who were transfused, 539/843 (63.9%) patients received PAM RBCs (Rhesus, Kell antigens minimum; median 6 RBCs); 36.1% received no‐PAM RBC units (median 8 RBCs). Of patients that received PAM RBCs, 258 had a subsequent antibody detection test ≥30 days post transfusion and 179 of the no‐PAM patients. The number of patients that developed RBC alloantibodies was not different in the two groups; 31 (12.0%) in the PAM group and 25 (14.0%) patients in the no‐PAM group (p = 0.5631).

Conclusion: This is the largest known assimilation of laboratory results from patients with WAA. The overall prevalence of WAA is quite low, and slightly higher when enriched with IRL results. Our data provide evidence that approximately one third of patients with WAA have alloantibodies concomitantly, and nearly 70% of patients with WAA require RBC transfusion. When there is pre‐existing WAA, subsequent development of alloimmunization is 12.0 – 14.0%. The use of PAM does not appear to be protective for subsequent RBC alloimmunization; however we did not study the number and type of serological evaluations that may have been impacted by using the PAM approach.

P5‐MN1‐6

Perioperative Red Cell Transfusions Are Associated with Post‐ Operative Venous Thromboembolism in Children and Neonates: Evidence from a Large North American Multicenter Prospective Registry

Ruchika Goel*1, Aaron Tobian2, Ravi M. Patel3, Melissa M. Cushing4, Ljiljana V. Vasovic4, Steven M. Frank5, Marianne E. Nellis4, Oliver Karam6 and Cassandra D. Josephson3

1Department of Pediatrics, New York Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Cornell Medicine, 2Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 3Emory University School of Medicine, 4Weill Cornell Medicine, 5Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, 6University of Geneva Faculty of Medicine

Background/Case Studies: In hospitalized children, the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is reportedly rising. RBC transfusion is commonly performed in the peri‐operative period in children; however, the relationship with post‐operative thrombotic events remains unclear. We have recently proposed this relationship in adults (Goel, Tobian et al, JAMA surgery, in press). This study examined the relationship between perioperative RBC transfusions and post‐operative VTE within 30 days of a surgery in children (<18 years).

Study Design/Method: Using the pediatric database of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (PEDS ACS‐NSQIP) (2012‐2014), risk‐adjusted outcomes for VTE (deep venous thrombosis (DVT(/pulmonary embolism(PE)) of pediatric patients (<18 years) undergoing elective/urgent/emergent surgeries were compared. Univariate followed by multivariable logistic regression was performed.

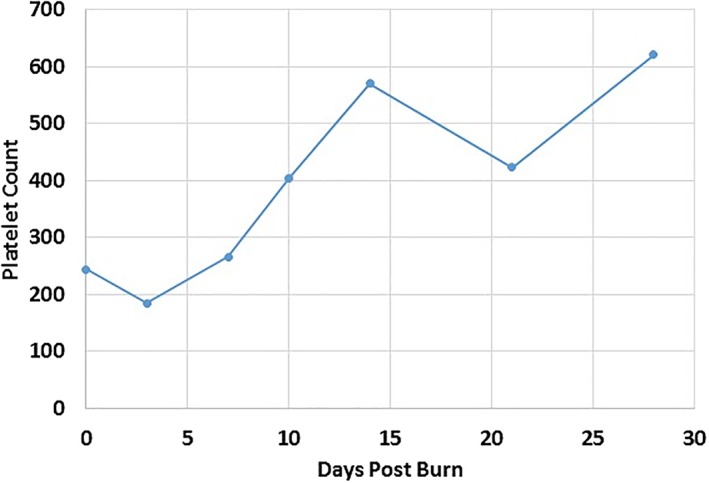

Results/Finding: N=183,233 children [39,211 infants (<1 year); 7,857 neonates (<28 days)] were evaluated. Of these 73.18% underwent elective, 10.03% urgent and 16.80% emergent procedures. Commonest surgery types were: general surgery 38.62%, orthopedic 19.68%, urologic 11.51%, otolaryngological 11.02% and neurosurgical 8.66%.

About 1.1% (n=1956) children [n=1129 (2.9%) infants; n=507 (6.45%) neonates] received pre‐operative transfusions (within 48 hours of surgery). Six percent (n=11,003) children [n=3,462 (8.83%) infants; n=1,101, (14.01%) neonates] received RBC transfusions intraoperatively (start of surgery until 72 hrs post‐op). Transfusions were in response to intra/post‐operative bleeding. 197 children (0.11%) [(n=74 (0.2%) infants; n=28 (0.36%) neonates)] had post‐operative VTE (including 10 (0.11%) cases of PE).

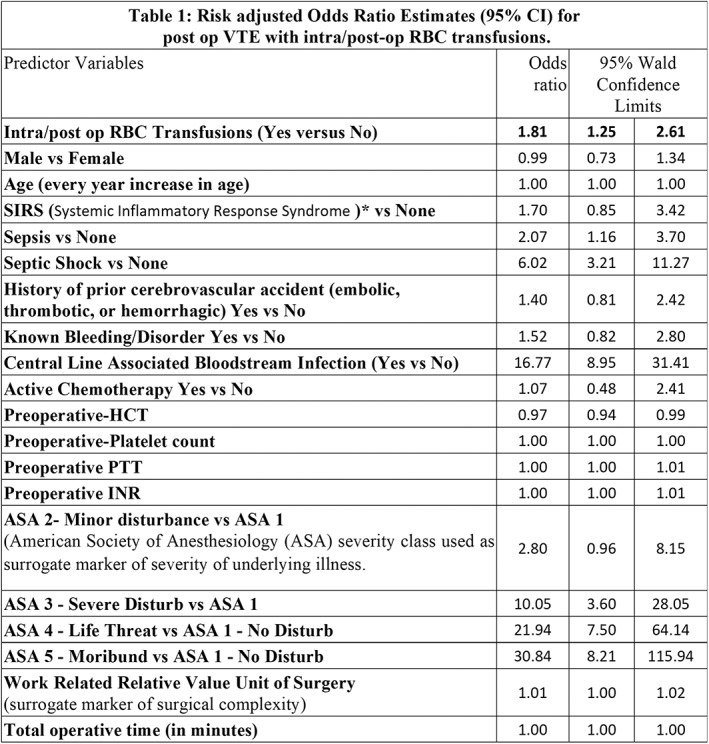

Intra/post‐operative RBC transfusions were associated with 1.8‐fold higher risk of VTE (adjusted odds ratio [adjOR]=1.81;95%CI=1.25‐2.61), p<0.001] after accounting for various putative risk factors (Table 1). The association was stronger in infants [adjOR = 3.2; 95%CI = (1.88‐5.43), p<0.001] and neonates [adjOR = 5.66; 95%CI = (2.30‐13.93), p<0.001].

(P5‐MN1‐6)

Pre‐operative RBC transfusions were independently associated with post‐operative VTE in all children [adjOR] = 2.30; 95%CI=1.43‐3.67), p<0.01], infants [adjOR = 2.55; 95%CI = (1.34‐5.43), p<0.01] and neonates [adjOR = 3.63; 95%CI = (1.36‐9.67), p<0.05].

Conclusion: In this prospective registry study of >180,000 children undergoing surgeries, peri‐operative RBC transfusions were associated with higher risk adjusted odds of post‐operative VTE. The relationship is also seen in subgroup analysis in infants and neonates.

Should these findings be validated in a prospective setting, peri‐operative pediatric patient blood management strategies need to be explored in these patients to optimize peri‐operative transfusions in children.

P6‐MN1‐6

Safety Analysis of a New Generation Freeze‐Dried Plasma Product: Report of a Dose‐Escalation, Phase 1 Clinical Trial

Jose Cancelas*1, Neeta Rugg1, Shawnagay Nestheide1, Melissa King2, Michele Snyder2, Joan C. Pehta3, Victor Macdonald4, Manoj Valiyaveettil4 and Andrew Atkinson4

1Hoxworth Blood Center, 2Westat Inc, 3Consultant to Vascular Solutions LLC, a subsidiary of Teleflex, Inc., 4USAMMDA

Background/Case Studies: Recent assessments of massive transfusion protocol outcomes have identified early transfusion of plasma results in improved hemostasis, shorter ventilator times and increased survival. Infusion using a ∼1:1 of plasma to red blood cells has also demonstrated a significant decrease in morbidity and mortality. Freeze‐dried plasma (FDP) products have been successfully used as an alternative to fresh‐frozen plasma (FFP), however, current FDP products prepared in glass bottles have limited widespread adoption of FDP in environments such as the battlefield. A new FDP product (RePlas®) that is contained and reconstituted in a plastic blood bag, using ∼ 250 mL USP sterile water for injection within less than two minutes, has been recently developed.

Study Design/Method: This was a prospective, paired, open label, single‐center, dose‐escalation phase 1 study to determine the safety of autologous infusions of whole blood (CPD) derived FDP or plasmapheresis (ACD) derived FDP into normal healthy subjects. Each FDP product was manufactured from a minimum volume of 270 mL of FFP. Three cohorts of 8 subjects per cohort were included (n=24), resulting in infusions of 270 mL (Cohort 1, n=4 for each CPD or n=4 for ACD FDP infusions), 540 mL (Cohort 2, n=4 for each CPD or n=4 for ACD FDP infusions) and 810 mL (Cohort 3, n=8 for ACD FDP and ACD FFP infusions). Cohort 3 was a randomized, double‐blind, crossover study that compared the clinical and laboratory levels of thrombogenesis biomarkers after FDP vs FFP infusions. Clinical and laboratory follow‐up was performed after 30 minutes, 4 hours, 24 hours, 7 and 28 days post‐infusion. in vitro biochemical and coagulation parameters including pH, osmolality, aPTT, NaPTT, INR, Factors V, VIII, VIIa, protein S, antithrombin III, and total protein levels were also analyzed. A data safety monitoring board reviewed the subjects’ data after the completion of infusions in each cohort.

Results/Finding: To date, a total of 41 subjects have been screened and 28 subjects have been enrolled and assigned to treatment. For cohorts 1 and 2, all 16 subjects have been infused with FDP products. All FDP units were reconstituted in less than two minutes. For all subjects, no serious adverse events (SAEs) related to product infusion and no occurrence of predetermined, treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) including thromboembolic events, infections, evidence of unusual bleeding/bruising or elevated D‐dimer levels have been observed. Physical examinations showed no significant changes in vital signs or Wells’ scores. Four AEs not related to the FDP product infusion were observed in cohort 1 (rhinitis, transient weakly positive DAT, hyperglycaemia and transient mild increase of liver transaminases). No AEs were identified in cohort 2. No signs of either local or systemic allergic reactions were observed after infusions. Cohort 3 infusions are ongoing and the results of this cohort will be presented.

Conclusion: Preliminary data suggest that RePlas® FDP is well tolerated in normal healthy volunteers with no SAEs or safety concerns.

Oral

Oral Abstract Session: Immune and Non‐Immune Factors Affecting Red Cell Survival

CBIB6‐MN3‐21

Peripheral Tolerance of Recent Thymic Emigrants Is Required to Prevent RBC‐Specific Autoimmunity

David R. Gruber, Amanda L. Richards, Andrea S.L. Wong, Heather L. Howie and Krystalyn E. Hudson*

BloodworksNW Research Institute

Background/Case Studies: Autoantibodies to RBCs may lead to autoimmune hemolytic anemia, a severe and sometimes fatal disease. While RBC‐specific B cells escape central tolerance and retain the ability to secrete autoantibodies, stringent T cell tolerance prevents autoimmunity; however, the tolerance mechanisms are unknown. Recent thymic emigrants (RTEs) are highly susceptible to tolerization. Herein, we tested the hypothesis that RTEs are involved in tolerance to RBC autoantigens.

Study Design/Method: HOD mice express an RBC‐specific transgene consisting of hen egg lysozyme, ovalbumin (OVA), and human Duffy. HOD mice were bred with OTII mice, whereby >90% of CD4 T cells are specific for OVA (within HOD). HODxOTII F1s were immunized with 100ug of OVA/CFA. Thymi from 8‐12 weeks (wks) old HODxOTII F1s were stained to identify OTIIs and regulatory T cells (Tregs). HOD mice were bred with OTII.Rag2p‐GFP (a.k.a. HODxRTE), where GFP is detectable in RTEs for 3 wks post thymic egress. GFP + OTII RTEs were evaluated for anergic surface markers, transcription factors, and kinases. To assess function, B6 mice received 3x105 sorted GFP + OTII RTEs from HODxRTE F1s followed by 100uL HOD RBCs. RTE proliferation was assessed at 3 days by Ki67 staining.

Results/Finding: OVA/CFA immunization failed to induce an immune response in HOD+OTII + mice (indicating robust tolerance); a strong antibody response was observed in HOD‐OTII + controls. In thymi, neither total CD4 OTII T cell number or frequency of FoxP3+CD25 + Tregs had a significant difference between HOD+OTII + and HOD‐OTII + controls, thereby indicating central tolerance mechanisms in not affecting RBC‐specific autoreactive T cells. RTEs from HODxRTE F1s were divided into GFPhi (<1 wks), GFPint (2‐3 wks), and GFPneg (mature) for analysis. GFPhi RTEs from HOD+RTE + mice had significantly higher expression of anergy‐associated transcription factors Egr2, NFAT2, and Helios and phosphorylation of mTOR and AKT, compared to HOD‐RTE + (p<0.05, 3/3 experiments). Anergic surface markers PD1, CD73, GITR, and FR4 increased expression as HOD+RTEs matured. RTEs from HOD‐RTE + mice displayed a naïve phenotype throughout maturation whereas autoreactive RTEs became CD44+CD62L‐ effector T cells. Following GFP + OTII adoptive transfer and HOD RBC transfusion, RTEs from HOD‐RTE + mice proliferated (>95% Ki67+) whereas decreased capacity to proliferate in maturing RTEs was observed in RTEs from HOD+RTE + mice (3/3 experiments, Ki67% RTEs: GFPhi 65, GFPint 35, GFPneg 15).

Conclusion: Data herein show that RBC‐specific autoreactive CD4 T cells are not subject to central tolerance mechanisms, which is a novel finding for an RBC autoantigen. Instead, an anergy program is initiated in RTEs during their maturation. These data provide key insights into RBC‐specific T cell tolerance mechanisms, identify a window of tolerization, and demonstrate that disruptions of RTE maturation and tolerance may lead to RBC autoimmunity.

CBIB5‐MN3‐21

Levels of STEAP3 Expression Are a Genetic Determinant of RBC Storage Quality in Mice

Heather L. Howie1, Ariel M. Hay1, Karen de Wolski2, Hayley Waterman1, Jenna Lebedev1, Xiaoyun Fu1, Yi Wang1, Angelo D'Alessandro3, Rachel Culp‐Hill4, Peter Thomson5, James D. Gorham6 and James C. Zimring*1

1BloodworksNW Research Institute, 2Bloodworks Northwest, 3University of Colorado Denver, 4University of Colorado, 5University of Sydney, 6University of Virginia School of Medicine

Background/Case Studies: There is substantial donor‐to‐donor variability in how well stored human RBCs circulate post‐transfusion. However, the basis of such variability is poorly understood. It has been reported, that like humans, RBCs from genetically distinct strains of mice store differently. The genetic element responsible for differences in storage between B6 mice (store well) and FVB mice (store poorly) was mapped.

Study Design/Method: 156 individual mice in the F2 generation of a B6 × FVB cross were analyzed with regards to: 1) 24‐hour post‐transfusion RBC recoveries (PTR), 2) high resolution metabolomics, and 3) SNP based genotyping. A phenotype driven backcross was also carried out; poorly storing progeny were crossed to B6 mice for 8 generations (B6.FVB congenic strain). New transgenic mice were engineered that overexpress Steap3 on their RBCs. Known human variants of human Steap3 were cloned and expressed in CHO cells and activity measured.

Results/Finding: Quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis of F2 mice identified a 149 Mb region on Chr 1 associated with PTR (p=2.09x10‐31). B6.FVB narrowed this to 2.8 Mb containing 20 coding genes. mRNA levels were quantified for all 20 genes by RT‐PCR in erythroid precursors. Only one gene, Steap3, showed significantly different expression in FVB and B6.FVB mice compared to B6 (p<.005 by 2‐way ANOVA, Bonferroni correction). Steap3 has two mRNA transcript variants in mice. Comparing FVB and B6.FVB mice to wild type B6, transcript var1 was 8‐10 fold higher while transcript var2 was 3 fold lower (p<.0001 and p<.05 respectively by 2‐way ANOVA, Bonferroni correction). RBCs from both FVB and B6.FVB mice had twice the Steap3 activity and 7 fold higher protein levels than B6 RBCs. Overexpressing Steap3 in B6 transgenic mice resulted in a significant decrease in PTR of stored RBCs compared to wild‐type B6 (p<0.001). Lipid oxidation correlated with poor PTR in the F2 cohort and refined clusters of oxylipins carried over into the B6.FVB strain and into Steap3 transgenic mice. Known natural variants of human Steap3 had a wide variety of activities.

Conclusion: Multiple lines of evidence using different approaches identified Steap3 as a genetic element regulating PTR. Steap3 is a ferrireductase converting Fe3 + to Fe2 + suggesting a mechanism of promoting a Fenton reaction with ensuing oxidation of lipids. Humans and mice share a Steap3 orthologue that is 84.97% identical at the amino acid level. Both null mice and deficient humans have a similar anemia. To our knowledge, this report is the first indication of a role of Steap3 in the biology of mature RBCs. Human Steap3 variants differ in activity but have not been tested for RBC storage. Testing this hypothesis in humans would require studies of PTR of RBCs from donors with genetic variation of Steap3, or other genes involved in Steap3 based pathways.

CBIB4‐MN3‐21

Red Blood Cell Alloimmunization Responses to Transfused Blood Do Not Require Splenic Marginal Zone Macrophages

Abhinav Arneja*1, Juan Salazar1, Manjula Santhanakrishnan2, Jeanne Hendrickson2 and Chance J. Luckey3

1University of Virginia, 2Yale University, 3University of Virginia Medical Center

Background/Case Studies: Alloimmunization to non‐ABO red blood cell (RBC) antigens remains a significant clinical problem in transfusion medicine. Presence of RBC alloantibodies can lead to delayed transfusion reactions resulting in significant morbidity and occasional mortality. Transfused RBCs represent a unique immune stimulus as they lack traditional pathogenic signals that stimulate innate immune responses. The molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in the stimulation of immune responses to transfused RBCs remain unclear. Recent work in mouse models has shown that storage of RBCs prior to transfusion leads to a significant enhancement of alloimmunization. Further studies have independently implicated macrophages and the spleen as being critical for immune response to stored RBCs. Splenic marginal zone macrophages (MZMs) have been reported to not only stimulate innate immunity but also to promote adaptive immune responses to certain blood‐borne pathogens. Additionally, Splenic MZMs specifically phagocytose intravenously injected apoptotic cells resulting in immune suppression towards apoptotic cell antigens. Uptake of apoptotic cells by MZMs critically depends on the exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) on their cell surface. Exposure of PS on the surface of RBCs increases with RBC age but is significantly enhanced by storage. We hypothesized that splenic MZMs phagocytose transfused stored RBCs and, unlike apoptotic cells, stimulate innate and adaptive immune responses to RBC antigens.

Study Design/Method: To investigate the role of MZMs in RBC alloantibody generation, we utilized the HOD mouse model to compare alloimmunization in Wild‐Type (WT) and Liver X Receptor α (LXRα) knock‐out (KO) mice. LXRα is a transcription factor essential for the generation of splenic MZMs. LXRα KO mice show a complete lack of splenic MZMs, and have abnormal responses to blood‐borne pathogens. WT and LXRα KO mice were transfused with fresh or stored HOD RBCs and resulting serum anti‐HOD IgG alloantibody titers were compared.

Results/Finding: Surprisingly, the lack of MZMs did not affect the generation of anti‐HOD IgG alloantibodies in response to either fresh or stored HOD RBCs. All WT and LXRα KO mice generated alloantibodies in response to transfused fresh or stored HOD RBCs (in 2/2 experiments with 5‐8 mice/group). Serum levels of anti‐HOD IgG titers were equivalent in WT and LXRα mice in response to transfusion with fresh (p = 0.18, 2/2 experiments with 5‐8 mice/group) or stored HOD RBCs (p = 0.51, 2/2 experiments with 5‐8 mice/group). Mann‐Whitney U test was used to calculate p‐values, and values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Conclusion: Splenic MZMs are not required for the primary alloantibody response to transfused fresh or stored HOD RBCs. Our results suggest that splenic immune responses to transfused RBCs utilize mechanisms that are distinct from those regulating immune responses to apoptotic cells and blood‐borne pathogens. This study further highlights the unique nature of RBCs as an immune stimulus, and stresses the need for continued investigation of molecular and cellular mechanisms regulating RBC alloimmunization.

CBIB3‐MN3‐21

IgG2c Alloantibodies Enhance RBC Alloimmunization by Modulating Antigen Presenting Cell Erythrophagocytosis

David R. Gruber, Kathryn Sheldon, Amanda L. Richards, Paurvi Shinde, Heather L. Howie, Jenna Lebedev, James C. Zimring and Krystalyn E. Hudson*

BloodworksNW Research Institute

Background/Case Studies: Prophylactic administration of polyclonal anti‐RhD in women prevents maternal alloimmunization. However, under certain conditions, some preparations of anti‐RhD have a paradoxical enhancement of alloimmunization. The underlying mechanisms behind modulation of humoral alloimmunization by anti‐RhD are unknown. However, recently it has become appreciated that different IgG subtypes of antibodies may differentially regulate alloimmunity. Herein, we take a reductionist approach and passively immunize mice with monoclonal alloantibodies, whereby the antibodies have the same specificity but are different IgG subtypes, to test how IgG subtype regulates RBC alloimmunization.

Study Design/Method: A new monoclonal anti‐Duffy was isolated, sequenced, and class‐switched into different mouse IgG subtypes (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG2c, IgG3). Individual subtypes were passively infused into C57BL/6 (B6) mice followed by a transfusion of 100uL of packed, leukoreduced RBCs consisting of 50uL HOD and 50uL B6, each labeled with lipophilic dyes to allow tracking. HOD RBCs express an RBC‐specific triple fusion protein consisting of hen egg lysozyme, ovalbumin (OVA), and human Duffy. Some recipients received an adoptive transfer of 105 OTII CD4 T cells, which recognize OVA contained within HOD, presented by recipient MHCII. Alloantibodies were assessed over 21 days and measured by flow crossmatch against HOD and control B6 RBC targets.

Results/Finding: Passive immunization with 1ug of IgG2a or IgG2c enhanced anti‐HOD alloantibody production (3/3 experiments, p<0.01), IgG2b led to a 3‐fold increase, but neither IgG1 nor IgG3 modulated alloimmunization, compared to controls. Additional mechanistic studies focused on IgG2c. Passive immunization with IgG2c accelerated HOD RBC clearance from circulation at every time point analyzed, compared to syngeneic B6 RBCs. Additionally, IgG2c treatment led to a significant increase of HOD RBC consumption (p<0.05, 3/3 experiments), with increases observed in CD8 + dendritic cells (DCs), CD8‐ DCs, red pulp macrophages, and to a lesser extent plasmacytoid DCs and neutrophils. The cumulative effect of altered RBC consumption patterns in IgG2c‐treated mice resulted in a significant increase in OTII proliferation (p<0.0001, 2/2 experiments).

Conclusion: The current findings indicate that pre‐existing anti‐RBC alloantibodies can modulate future RBC alloantibody production. In particular, IgG2c enhances alloantibody production through accelerated RBC clearance and shifting the pattern of consumption to individual immunostimulatory antigen presenting cell subsets. The cumulative effect of these changes is enhanced CD4 T cell activation and proliferation which leads to increased RBC alloantibodies. As polyclonal anti‐RhD contains multiple antibody subtypes at varying ratios, these finding may provide insight into why some preparations of RhD, under certain conditions, enhanced alloimmunization.

CBIB2‐MN3‐21

Enhancement of RBC Alloimmunization by IgG2a Requires Fcγri in a Murine Model

Paurvi Shinde1, Krystalyn E. Hudson1, Ariel M. Hay1, Jenna Lebedev1, Heather L. Howie1, Ellen Van Der Schoot2, Gestur Vidarsson3, Xiaohong Wang1 and James C. Zimring*1

1BloodworksNW Research Institute, 2Sanquin Blood Supply Research, 3Sanquin Research

Background/Case Studies: In addition to the better known effector function(s), antibodies are also known to regulate primary immune responses; e.g. administration of polyclonal anti‐RhD to prevent maternal alloimmunization. Attempts to generate monoclonal anti‐RhD have been complicated; ironically, some preparations enhanced rather than suppressed in human trials. Likewise, administration of plasma derived anti‐RhD has caused enhancement in some settings. The underlying factors and/or mechanisms that regulate enhancement or suppression are poorly understood. To investigate these processes, we used a tractable mouse model that expresses the K1 variant of Kell on RBCs, and allows transfusion of RBCs into antigen‐negative recipients as an allotransfusion.

Study Design/Method: A monoclonal anti‐K1 was isolated and sequenced. Recombinant DNA technology was used to express the same anti‐K1 variable domain as each of the different mouse IgG subtypes (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG2c, IgG3). Isolated subtypes were infused into C57BL/6 (B6) mice followed by transfusion of one unit of K1 RBCs (50 microliters). Alloimmunization was measured by testing serum for anti‐K1 IgM (at day 6) and IgG (at day 21) via flow crossmatch with K1 RBCs. Recipient mice included targeted deletions of the common gamma chain of FcgRs, FcgRI or FcgRIII. Both traditional and cellular surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assays were performed to assess affinity for IgG2a with the different FcgRs.

Results/Finding: IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG2c (but not IgG1 or IgG3) significantly enhanced alloimmunization. For example, in combined data from 3 experiments, IgG2a treated vs. control mice had IgM (1693 vs 357, p = 0.02) and IgG (5926 vs. 6.9, p = 0.002). No enhancement was observed using antibodies against a third‐party antigen. Likewise, no signal was detected in mice that received anti‐K1 antibody but no transfusion. Additional mechanistic studies focused on the IgG2a subtype. Enhancement by IgG2a was lost in mice with a deletion of the common Fc gamma chain (FcgR‐/‐), suggesting that FcgRI, FcgRIII or FcgRIV (or some combination) was required for enhancement. Enhancement by IgG2a was eliminated in FcgRI‐/‐ mice but was unaltered in FcgRIII‐/‐ mice. Additionally, SPR analysis revealed affinity of IgG2a was highest for FcgRI (1x9x10‐8). These findings demonstrate that FcgRI, but not FcgRIII is required for IgG2a mediated enhancement of alloantibody response to K1 RBCs.

Conclusion: The current findings indicate anti‐RBC antibodies can influence humoral alloimmunity and this process is dependent upon IgG subtype. IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG2c each enhanced alloimmunity. Mechanistically, IgG2a enhancement requires FcgRI. Because enhancement is lost in FcgRI null mice, then none of the other FcgRs is sufficient for enhancement; but we cannot rule out that they may be involved.

CBIB1‐MN3‐21

Mechanistic Analysis of Oxidant Stress Mediated Hemolysis in G6PD Deficient RBCs in a Novel Murine Model

Heather L. Howie1, Ariel M. Hay1, Jenna Lebedev1, Xiaoyun Fu1, Yi Wang1, Angelo D'Alessandro2, Mathew Wither3, Connie Zheng4, Matthew S. Karafin5, Steven L. Spitalnik6, Eldad A. Hod6, Richard O. Francis6, Tiffany A. Thomas6 and James C. Zimring*1,7

1BloodworksNW Research Institute, 2University of Colorado Denver, 3University of Washington, 4University of Colorado, 5BloodCenter of Wisconsin, 6Columbia University Medical Center, 7University of Washington School of Medicine

Background/Case Studies: Glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD‐def) is found in approximately 400 million humans, likely because it provides resistance to malaria. G6PD‐def is caused by missense mutation(s) that destabilize the enzyme, resulting in decreasing G6PD activity as RBCs age. Although typically healthy, G6PD‐def individuals can experience profound hemolysis upon exposure to oxidant stress through diet, drugs, or disease. However, many cellular and biological particulars of G6PD‐def remain poorly understood, partly due to the lack of an animal model with the same enzymatic instability seen in human G6PD‐def.

Study Design/Method: The coding region for a severe human G6PD‐def variant (Med‐) was knocked into the mouse G6PD locus on a C57BL/6 (B6) background. The G6PD‐def mouse RBCs were assessed for in vivo life span as well as for 24‐hour post‐transfusion recovery (PTR) after storage. Oxidant stress was induced in vivo with phenylhydrazine (PHZ); alternatively, RBCs were exposed to diamide in vitro. High resolution metabolomics analyses were performed on RBCs during challenge with PHZ or diamide, including in vitro incubation with stable isotopically labelled 13C1,2,3‐glucose to compare glycolysis vs. Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP).

Results/Finding: RBCs from G6PD‐def mice had 1.4% of wild‐type G6PD activity (p<0.0001) and metabolic 13C1,2,3‐glucose tracing confirmed decreased PPP flux, especially in diamide treated RBCs. At baseline, there was no observable difference in the in vivo RBC lifespan as compared to wild‐type mice. However, PHZ challenge caused marked hemoglobinuria and significantly increased RBC clearance in G6PD‐def compared to wild‐type mice over a 7‐day time course (p<0.01). G6PD‐def mice treated with PHZ had low steady state levels of 6‐phosphogluconate, sedoheptulose phosphate, and gluconolactone 6‐phosphate, in parallel with increased AMP/ATP ratios, decreased ATP, and increased polyamines, bilirubin, and nicotinamide. Recent human studies have shown a small but significant decrease in PTRs of stored RBCs from G6PD deficient donors compared to non‐deficient donors (81% + /‐ 7.2% vs. 86.8% + /‐ 2/8% ‐ p=0.001); no difference was observed in PTR of G6PD‐def vs. wild‐type mice.

Conclusion: Like many humans with G6PD‐def, these G6PD‐def mice are hematologically normal under healthy conditions and in the absence of oxidative stress. However, when exposed to environmental oxidative stress, RBCs undergo increased damage and rapid destruction. Metabolomics analysis provides unique insights into the insult that G6PD‐def RBCs suffer when exposed to oxidative stress. In addition to providing novel mechanistic insights into oxidative hemolysis of G6PD‐def RBCs, this model presents a new and tractable platform to investigate multiple hypotheses regarding oxidant stress in health and disease.

Oral Abstract Session: Transfusion Reactions/TACO and Septic Reactions

TS2‐MN3‐22

Transfusion Speed vs. Volume – Investigating Risk Factors of TACO

Robert Klanderman*1,2, Marije Wijnberge1,3, Joachim Bosboom3, Adrie Maas2, Margreeth Vroom1, Nicole Juffermans1,2, Markus Hollmann2,3, Bart Geerts3 and Alexander Vlaar1,2

1Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Academic Medical Center, 2Laboratory for Experimental Intensive Care and Anesthesiology, Academic Medical Center, 3Department of Anesthesiology, Academic Medical Center

Background/Case Studies: Transfusion‐associated circulatory overload (TACO) is one of the leading causes of transfusion‐related major morbidity and mortality. Hydrostatic pulmonary edema is key and major risk factors include speed and volume of transfusion. To date no preclinical studies have investigated infusion speed and volume on pulmonary capillary pressure. Our aim of this study was to develop a rat model for TACO and investigate the influence of these risk factors.

Study Design/Method: A ‘two‐hit’ rat model was developed using Lewis rats. Blood harvested from donor rats was used to make red blood cell units (RBC) following national blood banking practices. Under general anesthesia, a cardiac left‐ventricular pressure transducer was placed. Isovolemic anemia was induced by replacing 25% of circulating volume with colloid solution. A large myocardial infarction was induced through ligation of the left‐anterior descending coronary artery (first‐hit). Animals were randomized (n=3 per group) to receive 1, 2 or 4 units of RBCs in 30 or 60 minutes (second‐hit). Animals were followed‐up to 1‐hour post‐transfusion. Primary outcome was difference in left‐ventricular end‐diastolic pressure (dLVEDP) – gold standard for measuring increased pulmonary pressure (hallmark of TACO). Secondary outcomes include lung wet‐dry ratio (WDR) and hemodynamic parameters.

Results/Finding: Pre‐transfusion LVEDP was 9.64 mmHg (IQR: 8.1 – 11.1); following transfusion a significant increase in dLVEDP was seen between 1 vs. 2 and 1 vs. 4 units (resp.: p = 0.013, p = 0.013). While higher transfusion speeds trend towards higher pressures, this was not significantly different. Elevation of LVEDP above baseline persisted up to 1 hour after transfusion in the 2 and 4 unit group (ns.). WDR showed no differences between units or transfusion speed.

TABLE 1 (TS2‐MN3‐22) Difference in pulmonary capillary pressure – Speed vs. Volume

| Transfused: | dLVEDP:*(median) | Slow: (60 min) | Fast:* (30 min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Unit | −2.05 (−3.66 – −0.61)‡† | − 2.76 (−3.96 – −1.57) | −1.33 (−4.81 – −0.46)† |

| 2 Units | 0.50 (0.16 – 2.45) | 0.42 (−0.07 – 3.05) | 0.58 (−0.18 – 1.83) |

| 4 Units | 5.91 (4.13 – 6.37) | 5.80 (−1.29 – 6.15) | 6.02 (3.57 – 7.73) |

Data: median mmHg (IQR). *: dLVEDP significantly different within group. ‡dLVEDP significantly different compared to 2 units. †dLVEDP significantly different compared to 4 units.

Conclusion: This is the first animal transfusion model investigating the effect transfusion speed on pulmonary hydrostatic pressure, the key feature of TACO. A strong dose‐dependent effect of transfusion volume on pulmonary hydrostatic pressure was found. While higher transfusion speed showed a trend towards higher pressures, it was not significant in this model. Future experiments in this model will allow testing of interventions and therapeutic strategies to prevent TACO.

TS3‐MN3‐22

Improving the Sensitivity of Blood Product Culture to Detect Septic Transfusion Reactions in Adult Patients

Nancy M. Dunbar*1, Claudia S. Cohn2, Magali J. Fontaine3, Isabella Martin1, Andrew W.Y. Shih4, Meghan Delaney5 and Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) Collaborative1

1Dartmouth‐Hitchcock Medical Center, 2University of Minnesota, 3University of Maryland School of Medicine, 4University of British Columbia, 5Children's National Health System

Background/Case Studies: Culture of residual components can detect septic transfusion reactions (STR). According to AABB criteria, signs/symptoms suggestive of STR include 1) fever (>/=38C with a rise >/ = to 1C) PLUS any of the following: rigors, hypotension, shock, tachycardia, dyspnea and/or nausea/vomiting –OR‐ 2) isolated hypotension. Limitations of these criteria include that hypotension and tachycardia are undefined, fever may occur in the absence of other signs/symptoms, and fever may not occur in patients pre‐medicated with antipyretics. The goal of this project was to develop improved criteria for detection of STR by culture of residual product in adult patients.

Study Design/Method: We collected retrospective data for all transfusion reactions in adults ( > 15 years) that resulted in culture of the residual product during calendar year 2016. We also collected the same data for any reactions with positive residual product culture results from 2012‐2015, to enrich the dataset for positive results. We modified AABB criteria to define hypotension as systolic blood pressure </ = 90 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure </ = 60 mmHg –AND‐ decrease of 15% from baseline; and tachycardia as > / = 100bpm –AND‐ 15% increase from baseline. We also modified recommendations to culture when the fever was >/=39C in the absence of any other signs/symptoms or in the absence of fever when the patient was pre‐medicated with an anti‐pyretic and other signs/symptoms were present. We retrospectively determined the sensitivity and specificity of these modified criteria for the detection of positive cultures of residual components based on culture results.

Results/Finding: 22 institutions submitted complete reaction data for 807 cultured residual components, 64 of which had positive culture results. Six were considered definite STR (patient cultures grew the same organism); 58 were considered possible STR (patient culture was negative, discordant, or the patient was not cultured). Performance of modified criteria compared to AABB criteria is shown in the table. Modified criteria identified all definite STR, while AABB criteria would have missed one. More cultured reactions were consistent with the modified criteria than with the AABB criteria.

Conclusion: Modified criteria for culturing residual components for suspected STR in adult patients offer better sensitivity for detection of a positive culture result but are less specific.

(TS3‐MN3‐22)

| AABB | MODIFIED | |

|---|---|---|

| Meets Criteria for Culture | 296 (37% of reactions) | 413 (51% of reactions) |

| Positive Culture (N=64) | 27 (42% of positives) | 44 (69% of positives) |

| Definite STR (N=6) | 5 (83%) | 6 (100%) |

| Possible STR (N=58) | 22 (38%) | 38 (66%) |

| Sensitivity | 42% (95% CI: 30‐55%) | 69% (95% CI: 56‐79%) |

| Specificity | 64% (95% CI: 60‐67%) | 50% (95% CI: 47‐54%) |

TS19‐MN3‐22

Low Rate of Patient Culturing in Possible Septic Transfusion Reactions

Isabella Martin*1, Claudia S. Cohn2, Meghan Delaney3, Nancy M. Dunbar1, Magali J. Fontaine4, Andrew W.Y. Shih5,6 and Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) Collaborative1

1Dartmouth‐Hitchcock Medical Center, 2University of Minnesota, 3Children's National Health System, 4University of Maryland School of Medicine, 5Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, 6University of British Columbia

Background/Case Studies: When a septic transfusion reaction (STR) is suspected, AABB Bulletin 14‐04 recommends testing the returned product for bacterial contamination as well as drawing blood samples from the patient for culturing. Growing the same bacterial species from these two sources supports a diagnosis of STR. However, patient blood cultures can be negative in the setting of a true STR if the patient is on antibiotic therapy at the time of transfusion. This multicenter, retrospective, international study describes 1) the rate of patient culturing in the setting of product culturing and 2) organisms detected from these cultures.

Study Design/Method: We collected data for all transfusion reactions with residual product culture during the calendar year 2016, including recipient demographic data, type of product implicated, and patient and/or product culture results. The data set was additionally enriched with all cases from 2012‐2015 where product culture was positive. Imputability of the clinical significance of a positive product culture was defined as “definite STR” if the patient culture grew the same organism and “possible STR” if patient was not cultured or if the culture 1) was negative or 2) grew a different organism from the product.

Results/Finding: Out of 1,174 transfusion reactions with product culture at 22 institutions, only 449 (38%) patients were concurrently cultured. Eighty‐eight (7%) product cultures grew a bacterial organism. Of those positive product cultures, 13/88 (15%) had concordant patient cultures (“definite” imputability). The organisms implicated were either members of the skin microbiota (8/13) such as Staphylococcus spp. or of the gastrointestinal tract (5/13) such as Escherichia coli. In 6/88 (7%) cases, patient blood culture grew a non‐concordant organism (Table) and in 46/88 (52%) cases patient cultures were negative (“possible” imputability). In the remaining 23/88 (26%) cases, the patient was not cultured (unable to assess imputability).

Conclusion: A minority of patients had concurrent blood cultures obtained when a residual product was cultured during the workup for STR. Imputability therefore could not be assigned in 26% of positive product cultures. Isolation of the same bacterial species from the patient and the product allowed for assignment of “definite” imputability in 15% of cases with positive product culture. If transfusion reaction signs and symptoms warrant culture of the residual product, a patient blood culture should be collected concurrently to aid in interpreting product culture results.

(TS19‐MN3‐22)

| Product Culture | Patient Culture | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Proprionibacterium spp. | Group G Streptococcus |

| 2 | Coagulase‐negative Staphylococcus (CNS) | E. coli |

| 3 | CNS | Enterococcus faecalis |

| 4 | Corynebacterium spp. | CNS |

| 5 | CNS | E. coli |

| 6 | CNS | E. coli |

TS22‐MN3‐22

Marked Variation in Culturing for Septic Transfusion Reactions: Opportunity for Practice Standardization

Andrew W.Y. Shih*1,2, Meghan Delaney3, Nancy M. Dunbar4, Magali J. Fontaine5, Isabella Martin4 and Claudia S. Cohn6

1University of British Columbia, 2Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, 3Children's National Health System, 4Dartmouth‐Hitchcock Medical Center, 5University of Maryland School of Medicine, 6University of Minnesota

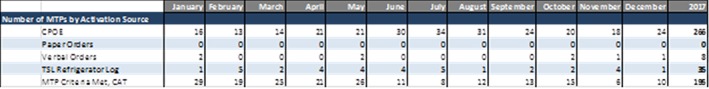

Background/Case Studies: Transfusion of blood components contaminated with bacteria may result in septic transfusion reactions (STRs), which can result in morbidity and/or mortality for the transfusion recipient. Culturing the residual component after a suspected STR is important as it may guide management of patients and co‐components. Although guidelines exist for when to culture residual component in setting of suspected STR, current practices are unknown. The aim of this project was to measure reaction reporting and residual component culturing rates and assess institutional policies for detection of STR by culture of residual components.

Study Design/Method: We retrospectively collected data for the total number of transfusions, transfusion reactions reported, and cultured residual components for all transfusion reactions in calendar year 2016; stratified by implicated component type: red blood cells (RBCs), plasma, and platelets (PLTs). To contextualize this data, a survey was distributed to all study participants to assess institutional policies for investigating STRs.

Results/Finding: Data and survey responses were received from 20 centers encompassing 730,006 transfusions, 3,151 reported reactions, and 1,005 cultured reactions. There was marked variation in reaction reporting (0.1‐1.3%) and culturing rates (0.0‐100.0%) across centers. Although reaction reporting rates were lower for plasma when compared to PLTs and RBCs (p<0.0001), no difference in reaction culture rates by component type were observed (Table).

Survey results demonstrated marked variation in institutional culturing policies. The majority (13/20; 65%) of centers do not use published criteria for culturing STRs. Some centers allow culturing of residual units without medical director approval (7/20; 35%) and have no formal review process to trigger STR investigation (5/20; 25%). Centers that reported a historically clinically relevant STR had overall higher reaction culture rates (55.1% vs 18.3%; p<0.0001), suggesting recall bias may be a driver for increased culturing.

Conclusion: There is marked variation in institutional practices surrounding culturing residual components to detect STRs. Historically reported clinically relevant STR appears to result in higher culture rates. There is opportunity for practice standardization.

(TS22‐MN3‐22)

| Transfusion Reaction Reporting Rate | Transfusion Reaction Culturing Rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implicated Product | % Mean (Range, SD) | p value (relative to PLTs) | % Mean (Range, SD) | p value (relative to PLTs) |

| RBCs | 0.5 (0.1‐1.5, 0.4) | 0.14 | 30.7 (0.0‐100.0, 31.7) | 0.83 |

| PLTs | 0.7% (0.1‐2.0, 0.5) | Reference | 32.8 (0.0‐100.0, 30.9) | Reference |

| Plasma | 0.2% (0.0‐0.5, 0.1) | < 0.0001 | 19.6 (0.0‐100.0, 27.3) | 0.15 |

TS23‐MN3‐22

Transfusion‐Associated Circulatory Overload – Understanding the Pathogenesis

Robert Klanderman*1,2, Joachim Bosboom3, Marije Wijnberge1,3, Adrie Maas2, Margreeth Vroom1, Nicole Juffermans1,2, Markus Hollmann2,3, Bart Geerts3 and Alexander Vlaar1,2

1Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Academic Medical Center, 2Laboratory for Experimental Intensive Care and Anesthesiology, Academic Medical Center, 3Department of Anesthesiology, Academic Medical Center

Background/Case Studies: Transfusion‐associated circulatory overload (TACO) is one of the leading causes of transfusion‐related morbidity and mortality. By definition, TACO is caused by hydrostatic pulmonary edema due to circulatory overload. The exact pathophysiology however is unclear, as up to 50% of cases occur after only 1 transfused unit. To date no animal models have been able to induce TACO, since healthy hearts are able to deal with large infused volumes. We hypothesized underlying volume incompliance, e.g. cardiac dysfunction, and subsequent transfusion causes TACO. Our aim was to induce TACO in an animal model and investigate the pathophysiology.

Study Design/Method: A ‘two‐hit’ TACO model was developed using Lewis rats. Under general anesthesia, the left‐ventricle was catheterized. Using colloids, 25% of circulating volume was replaced to induce isovolemic anemia. A large myocardial infarction was induced through ligation of the left‐anterior descending coronary artery (‘first‐hit’). Rats were randomized (n=3 per group) to receive 2 or 4 units of RBCs prepared from donor rats or similar volume of lactated ringers (LR) over 30 minutes (‘second‐hit’). Animals were followed for 1‐hour post‐transfusion. Primary outcome was left‐ventricular end‐diastolic pressure (LVEDP) – gold standard for measuring increased pulmonary capillary pressure (hallmark of TACO). Secondary outcome was lung water‐content.

Results/Finding: Baseline hemodynamics were similar between groups and LVEDP was 9.2 mmHg (IQR: 8.0 – 12.2). A large increase in LVEDP (Table 1.) was seen directly after infusion of 4 RBCs but not with LR (p<0.05). Post‐transfusion LVEDP dissipated more rapidly in the fluid infusion group at 30 and 60 minutes (p<0.05) but was not significant anymore after 1‐hour. Lung water‐content did not differ between groups.

TABLE 1 (TS23‐MN3‐22) Difference in LVEDP between RBCs and LR.

| Units (n=): | Change in LVEDP (mmHg): | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LR | RBC | ||

| Pre‐ vs. post‐trx | 2 | −0.73 (−2.63 – 1.64) | 0.58 (0.20 – 1.83) |

| 4 | 1.17 (0.00 – 1.41) | 6.02 (4.80 – 7.70)* | |

| Pre‐ trx vs. 30 min post−trx | 2 | −3.93 (−4.02 – −1.96) | −0.76 (−1.01 – −0.51) |

| 4 | −4.27 (−4.84 – −2.74) | 2.69 (1.85 – 3.35)* | |

| Pre−trx vs. 1−hour post−trx | 2 | −5.14 (−5.65 – −2.64) | −0.77 (−1.53 – −0.77) |

| 4 | −5.30 (−5.73 – −2.63) | 0.01 (−0.36 – 2.22) | |

Data: median (IQR). *: p<0.05 compared to LR group. trx: Transfusion

Conclusion: In this ‘two‐hit’ model of anemic rats with underlying cardiac dysfunction, blood but not fluid infusion increased pulmonary capillary pressure. This TACO model is the first to compare fluids to blood products and measure both direct pulmonary capillary pressure and pulmonary edema. Blood transfusion has a profoundly different effect on capillary pressure in the lungs, the study is currently underpowered to detect differences in pulmonary edema however inclusion is ongoing. This data suggests TACO pathophysiology is more than solely fluid overload.

TS24‐MN3‐22

Classification Tree Algorithms to Identify Patients at Risk for Transfusion‐Associated Circulatory Overload

Nareg Roubinian*1, Dhuly Chowdhury2, Darrell Triulzi3, Jeanne Hendrickson4, Jerome Gottschall5, Mars Stone1, Daryl J. Kor6, Mark R. Looney7, Michael Matthay8, Donald Brambilla2, Steve Kleinman9 and Edward Murphy10

1Blood Systems Research Institute, 2RTI International, 3The Institute for Transfusion Medicine, 4Yale University, 5BloodCenter of Wisconsin, 6Mayo Clinic, 7UCSF, 8University of California at San Francisco, 9AABB, 10Blood Centers of the Pacific‐Irwin Center

Background/Case Studies: Transfusion‐associated circulatory overload (TACO) is a common and often severe adverse reaction of blood transfusion associated with increased morbidity and mortality. We sought to develop a predictive algorithm which would use pre‐transfusion patient characteristics to identify patients at high risk for developing TACO before they are transfused.

Study Design/Method: A case control study at four academic hospitals utilized active surveillance to enroll cases of TACO as well as matched transfused controls without pulmonary edema. A measure of cardiac stress, N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP), was measured in cases of TACO and controls prior to and following transfusion. Case detection algorithms to identify patients at the highest risk of TACO were developed using classification and regression tree (CART) analyses. We evaluated approximately 50 pre‐transfusion risk factors and produced a ranking of 7 most important predictors in order of their relative importance for predicting TACO. Algorithm performance was evaluated using 10‐fold cross‐validation with misclassification error rates, average square error (ASE), sensitivity and specificity. Receiver operating characteristics curve analyses were used to determine the accuracy of pre‐transfusion clinical predictors in differentiating TACO from controls.

Results/Finding: The most informative determinants for cases of TACO (n=200) versus control status (n=405) were: pre‐transfusion SpO2/FiO2 (SF) ratio, NT‐proBNP level, hospital setting, history of hypertension, elevated systolic blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pre‐transfusion hemoglobin level > than 7 g/dL. Patients with pre‐transfusion SF ratios less than 450, NT‐proBNP levels greater than 1060, and OR/PACU, emergency department, or procedural suite settings had the highest probability of developing TACO (86%). Patients with pre‐transfusion SF ratio greater than 450 and respiratory rate less than 16 had the lowest probability of developing TACO (5%). Algorithm performance had excellent discrimination for TACO (n=200) vs. control (n=405) with the area under the curve = 0.83. CART analysis achieved a misclassification rate of 21%, an ASE of 15%, a sensitivity of 63%, and a specificity of 85%.

Conclusion: A CART‐based screening algorithm differentiated cases of TACO from transfused controls using only pre‐transfusion clinical data in a case‐control setting. Classification tree algorithms may improve identification of patients at risk for developing TACO. Prospective studies are needed to assess the utility of real‐time predictive algorithms plus clinical interventions in preventing TACO in a large‐scale hospitalized patient cohort.

Oral Abstract Session: Transfusion Testing & Hemovigilance

TS9‐MN3‐23

Acute Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions in Massachusetts, 2015‐2017

Melissa Cumming*1, Christina Brandeburg1, Alexandra DeJesus1, Michele Herman2, Lynne O'Hearn3, Lynne Uhl2, Chester Andrzejewski4 and Karen Quillen5

1Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 3Baystate Medical Center, 4Baystate Health / Baystate Medical Center, 5Boston Medical Center

Background/Case Studies: Mandatory reporting of adverse reactions and monthly transfusion activity to the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) has been in place in Massachusetts since June, 2014. Here we report incidence and mechanism of acute hemolytic transfusion reactions (AHTR) over a three‐year period.

Study Design/Method: AHTRs reported from 2015‐2017, that met NHSN case definition and imputability criteria of definite, possible, or probable were included from 70 facilities. We analyzed and categorized reaction mechanism, immune versus non‐immune, severity, implicated blood component, recipient characteristics, and transfused component ABO/Rh type using SAS 9.3. Rates were calculated per 10,000 units transfused.

Results/Finding: 35 AHTRs were reported with a mean of 11.7/year. The rate was 0.32 per 10,000 units transfused (all product types) or approximately 1 in 31,000. The majority of AHTRs, 91% (32/35) were reported by larger facilities ( ≥ 300 beds) where the rate was 0.40 per 10,000 units transfused compared to 0.10 per 10,000 units transfused for facilities with < 300 beds. Immune mechanisms accounted for 83% (29/35) of AHTRs. ABO antibodies were responsible for 41% (12/29) of immune AHTRs; 9 of which involved group O apheresis platelets (without platelet additive solution) transfused to group A (or AB) recipients. The incidence of AHTR in platelet transfusions was 0.63 per 10,000 platelet units or approximately 1 in 15,000. The other 3 ABO AHTR cases involved red blood cell (RBC) transfusions to an ABO‐incompatible stem cell transplant recipient, an A2 subgroup patient, and one case of erroneous ABO‐incompatible RBC unit (group AB) transfusion to a surgery patient (group A). Autoantibodies accounted for 28% (8/29) of immune AHTRs; 7/8 of these cases involved warm autoantibodies. Alloantibodies (2 cases each of anti‐C and anti‐Fy(a), 1 case each of anti‐Le(a), anti‐e, anti‐E, anti‐D, and anti‐K) accounted for the remainder of immune AHTRs. The incidence of AHTR in RBC transfusion was 0.35 per 10,000 RBCs or approximately 1 in 28,000. Although 26% (9/35) of reactions were categorized as severe, only one reaction was noted to have major long‐term sequelae. That case involved a patient who required massive transfusion with 6 pre‐existing alloantibodies (anti‐E, c, K, Fy3, s, and N).

Conclusion: Group O apheresis platelets transfused to group A (or AB) recipients represented the largest category of immune AHTRs over the three‐year period, followed by autoantibodies implicated in red blood cell transfusions. Hemovigilance reporting using NHSN allows for standardized, reaction‐specific analysis over time, and can identify opportunities for improvement. These findings are reassuring that AHTRs are rare in Massachusetts.

TS13‐MN3‐23

Transfusion‐Associated Circulatory Overload in Massachusetts, 2015‐2017

Melissa Cumming*1, Christina Brandeburg1, Alexandra DeJesus1, Michele Herman2, Lynne O'Hearn3, Lynne Uhl2, Karen Quillen4 and Chester Andrzejewski5

1Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 3Baystate Medical Center, 4Boston Medical Center, 5Baystate Health / Baystate Medical Center

Background/Case Studies: Massachusetts blood banks have been required by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) to submit monthly transfusion activity and adverse reaction data to the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Hemovigilance Module since June, 2014. Such standardized statewide data collection allows for more comprehensive analyses, including the potential to generate local benchmarks. Transfusion‐Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO) is currently of interest due to international discussions of proposed modifications to the current surveillance case definition. As a result of perceived local increase in TACO incidence, we examined data submitted involving TACO and report the findings here.

Study Design/Method: TACO reactions (2015‐2017) meeting the NHSN case definition and imputability criteria of possible, probable, or definite from 70 facilities, were included. We analyzed by age, gender, product received, transfusion indication, hospital bed size, and selected clinical criteria using SAS 9.3. Rates were calculated per 10,000 units transfused.

Results/Finding: 205 TACO reactions were reported with a mean of 68.3/year. Of these, 107(52%) were in females, 45(22%) were aged 50‐59, and 51(25%) were aged 70‐79 years. Notably, two were aged ≤ 18. Facilities with ≥ 300 beds reported 160(78%) TACO reactions, 23(11%) occurred in those with 100‐299 beds, and 22(11%) in those with < 100 beds. The rate of TACO per 10,000 units transfused was 5.14 in facilities with < 100 beds, 0.88 in those with 100‐299 beds and 2.01 in those with ≥ 300 beds. Indication for transfusion was documented for 124/205(60%), with “medical” 44% (n=54) being most frequent followed by malignancy 17% (n=21), internal bleeding 13% (n=16), hematologic disorder 10% (n=12), and surgery 8% (n=10). Seasonal variation was observed with the lowest incidence of TACO occurring in June and July. The rate of TACO increased from 1.64 to 2.08/10,000 units transfused over the study period. The three‐year TACO rates per 10,000 units transfused by product type were 1.09 for plasma, 1.54 for platelets and the highest was 2.00 for RBCs.

Conclusion: A modest increase in TACO was observed over the three‐year period, as well as a bi‐modal age distribution among cases. The seasonal variation and higher rate among smaller facilities provides guidance to target awareness and potential interventions. Limitations include a lack of external data validation and the possibility of inconsistent case definition interpretation and application. This study demonstrates the utility of NHSN for trend identification and selected reaction analysis and targeting of transfusion safety efforts.

TS15‐MN3‐23

Transfusion of Incorrect Blood Components (IBCT) Reported to the Norwegian Hemovigilance System

Aurora Espinosa*, Øystein Flesland and Christine Torsvik Steinsvåg

The Norwegian Directorate of Health

Background/Case Studies: The Norwegian hemovigilance system was implemented in 2004 as a voluntary reporting system, becoming mandatory for serious adverse events in 2007. In the Norwegian hemovigilance system, IBCT has been reported as a transfusion complication, even when the patient did not experience any symptoms.

Study Design/Method: IBCT is defined as the transfusion of a blood component intended for another patient or the transfusion of a blood component which does not comply with the specified requirements. Clinical reactions and severity, as well as the cause of the errors were registered, including errors in ordering of the blood component, selection and issuing, labeling, testing and bedside patient identification.

Results/Finding: In the period 2004–15 the Norwegian hemovigilance system received 240 cases of IBCT, including 104 cases of blood component transfused to the wrong patient and 132 cases of blood component not meeting the specified requirements. In four additional cases, the blood component both failed to meet the expected requirements and was transfused to the wrong patient. Examples of non‐conformities regarding lack of specified requirements of the blood component are lack of irradiation when required and transfusion of incompatible red cells in the presence of previously identified red cell antibodies. Thirty‐five of the reported IBCT occurred in patients under the age of twenty. In 28 of these cases the transfused blood component did not meet specified requirements. In more than 50 % of the total number of cases there were multiple errors. There were 26 reports on hemolytic transfusion reactions caused by IBCT, twenty of them ABO incompatibility cases and six cases caused by incompatibility in other blood group systems than ABO, even if the antibody was known prior to the transfusion. Nine of the ABO‐incompatible blood transfusions were less severe reactions, ten were serious or life‐threatening and three were fatal. Two patients with known anti‐IgA had an anaphylactic reaction after the transfusion of a red blood cell concentrate. Most of the patients receiving an incorrect blood component had no adverse reaction. Errors were most frequently related to ordering of blood components by the clinical departments, selection and issuing of blood components by the blood bank and to inadequate bedside patient identification prior to the transfusion. One can assume that in all cases where the patient received a blood component intended for another patient, the bedside patient identity control was not performed according to the local guidelines.

Conclusion: Errors occur in all areas of the transfusion chain and in a high number of cases multiple errors are made. Most cases of blood components transfused to the wrong patient could have been prevented if adequate bedside patient identification had been performed. The main cause leading to IBCT are errors regarding ordering of blood products and inadequate bedside patient identification. In patients under the age of twenty the main cause for IBCT is transfusion of a blood component not meeting the specified requirements especially irradiation. The Norwegian hemovigilance system has strongly recommended the use of electronic patient identification before transfusion to reduce the number of transfusions of a blood component intended for another patient, but only a few hospitals in Norway have implemented such a system.

TS20‐MN3‐23

Weak D Testing and Rh Immune Globulin Management in Mothers and Newborns: A Blinded Specimen‐Testing Survey of 81 Transfusion Services

Glenn Ramsey*1, Yara A. Park2, Meghan Delaney3,4, Lamont Thomas5, Rhona Souers5 and CAP Transfusion Medicine Resource Committee5

1Northwestern University, 2University of North Carolina, 3Children's National Health System, 4George Washington University, 5College of American Pathologists

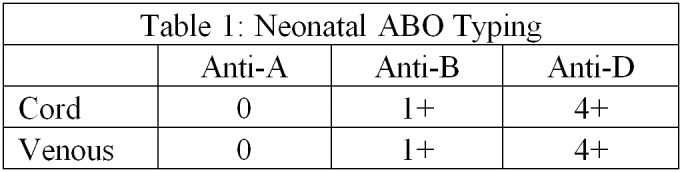

Background/Case Studies: An interdisciplinary task force recommended that obstetric (OB) patients with RhD agglutination results graded as ≤2 + should be managed as RhD‐negative (neg) unless weak D (WKD) genotyping confirms they are WKD type 1, 2 or 3 in which case they can be managed as RhD + (Transfusion 55:680, 2015). We devised an educational survey with WKD RBC samples to benchmark current practices for WKD testing and RhIG management.

Study Design/Method: Participating laboratories received two unknown (blinded) 5% RBC suspensions with two case histories: 1) a mother‐to‐be and then mother of an RhD + baby (“mother”); 2) a newborn baby from an RhD‐neg mother (“baby”). Both samples were created from the same WKD blood donor. Participating laboratories were instructed to use their routine RhD tube typing methods for both samples. Participants provided their serological reactions; RhD type interpretations; RhIG recommendations; fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH) screening methods; and facility RHD genotyping experience in WKD mothers. Comparisons between centers’ responses utilized Fisher's two‐tailed exact test

Results/Finding: Results from 81 mainly US labs with OB services were analyzed. For the “mother”: 1) 84% of labs would have given RhIG (Table); 2) labs with immediate‐spin‐positive (IS+) anti‐D reactivity were less likely to give RhIG than labs with negative IS (68% v 89%, p=0.04); and 3) labs which performed antiglobulin testing (AGT) after IS‐neg results were less likely to give RhIG (69% vs 98%, p<0.01). The 4 anti‐D reagents yielded different IS + rates (p=0.02). For the “baby” 34/74 labs (46%) would do fetal rosette testing (FRT) for excess FMH in their mothers, including 25/53 (47%) for babies typed as IS‐neg AGT+. Labs used diverse verbiage for Rh reports: D neg, WKD, RhD indeterminate, Du or D+. In 44/73 (60%) of responding labs, RHD genotyping was done in selected or all WKD + OB cases.

Conclusion: Participants obtained a broad range of RhD typing reactions for WKD RBCs, influenced by anti‐D reagents, which affected the use of RhIG. FRT can miss excess FMH from WKD babies, but 46% of labs would have used it. A confusing array of terminology was used for reporting WKD types.

(TS20‐MN3‐23)

| RhD Serology and RhIG Therapy (Rx) | Reagent Serology and RhIG | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | Mother RhIG Rx/all | Baby Mom RhIG Rx/all | Vendor | Mother IS pos/all | Mother RhIG Rx/all | ||||

| IS neg, no AGT | 40/41 | 98% | 3/3 | 100% | Alba | 2/6 | 33% | 3/6 | 50% |

| IS neg, AGT neg | 0 | 0/3 | 0% | Bio‐Rad | 5/16 | 31% | 16/16 | 100% | |

| IS neg, AGT+ | 11/16 | 69% | 53/54 | 98% | Immucor | 15/37 | 41% | 27/36 | 75% |

| All IS negative | 51/57 | 89% | 56/60 | 93% | Ortho | 1/21 | 5% | 19/20 | 95% |

| IS wk‐2+, AGT+ | 9/11 | 82% | 12/12 | 100% | Other | 0/1 | 0% | 1/1 | 100% |

| IS wk‐2+, no AGT | 6/9 | 67% | 6/7 | 86% | Total | 23/81 | 28% | 66/79 | 84% |

| IS ≥ 3+, no AGT | 0/2 | 0% | 0 | ||||||

| All IS positive | 15/22 | 68% | 18/19 | 95% | |||||

| Total | 66/79 | 84% | 74/79 | 94% | |||||

TS21‐MN3‐23

It's Complicated: Multiplicity and Uncertainty in Respiratory Transfusion Reaction Conclusions

Christine Cserti‐Gazdewich*1, Reda Siddiqui1, Alioska Escorcia1, Farzana Tasmin1, Lani Lieberman1, Jacob Pendergrast1, Yulia Lin2 and Jeannie Callum2

1University Health Network, 2Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

Background/Case Studies: Each transfusion entails the risk of an acute disturbance, be it febrile (F), allergic (A), and/or cardiorespiratory (C) at presentation. Although the overall odds of transfusion reactions (TR) are low and most are minor, respiratory transfusion reactions (RTRs) are likelier to be severe, and are the leading cause of transfusion‐related morbidity and mortality. RTRs may be cardiogenic (transfusion‐associated circulatory overload [TACO]) and/or non‐cardiogenic. The latter range from direct insults (transfusion‐related acute lung injury [TRALI], or allergic bronchopulmonary transfusion reaction [ABTR]), to indirect manifestations of other injuries (bacterial contamination, or acute hemolytic incompatibility). If criteria are not met for these harms, and underlying disease progression is not playing a role, then the diagnosis of exclusion is transfusion associated dyspnea (TAD). TRs, and RTRs in particular, can be challenging to investigate in patients with complex comorbidities, and in the working environment with its information gaps. The extent to which TR patients present with multiple disturbances, and the extent to which reviewers can reach conclusions more certain than merely “possible,” is of interest to measure in TR investigations, and especially in RTRs.

Study Design/Method: In the hemovigilance database of an academic adult healthcare institution (comprising 3 sites transfusing 55,000‐65,000 components/year), consecutive TR were retrospectively analyzed for mode of presentation (F/A/C), with multiple modes of presentation counted as a measure of complexity. Final conclusion(s) and respective conclusion‐specific certainty/imputability underwent review to gauge diagnostic confidence. RTRs were also analyzed for the number of conclusions reached per case, and for the frequency of TACO, TRALI, ABTR, and TAD as a conclusion (and their respective certainties).

Results/Finding: Over 5 years (01/01/2013 ‐ 31/12/2017), 1691 TR were investigated by the transfusion laboratory team. Fever occurred in 764 cases, while RTR was noted in 346 (20.5%). Referrals with more than one disturbance (eg. F+C) occurred in 265 cases (15.7% of referrals). The provisional diagnosis in the TR referrals was ultimately no more certain than “possible” in 188 cases (11.1%). In RTRs, there were 451 conclusions reached, a value 30% greater than the number of referrals. When conclusions were stratified between those of low confidence [possible/cannot rule out] versus high confidence [probable or definite], the weight was low confidence‐skewed in most RTR categories (95/80 in TACO, 24/0 in TRALI, and 113/22 in TAD, versus 52/65 in ABTR, respectively). Overall, the ratio of low confidence to high confidence RTR conclusions was 1.7:1. TAD was coded 135 times, and was the commonest conclusion after TACO.