Abstract

This study has two goals. The first is to explain the geo-environmental determinants of the accelerated diffusion of COVID-19 that is generating a high level of deaths. The second is to suggest a strategy to cope with future epidemic threats similar to COVID-19 having an accelerated viral infectivity in society. Using data on sample of N = 55 Italian province capitals, and data of infected individuals at as of April 7th, 2020, results reveal that the accelerate and vast diffusion of COVID-19 in North Italy has a high association with air pollution of cities measured with days exceeding the limits set for PM10 (particulate matter 10 μm or less in diameter) or ozone. In particular, hinterland cities with average high number of days exceeding the limits set for PM10 (and also having a low wind speed) have a very high number of infected people on 7th April 2020 (arithmetic mean is about 2200 infected individuals, with average polluted days greater than 80 days per year), whereas coastal cities also having days exceeding the limits set for PM10 or ozone but with high wind speed have about 944.70 average infected individuals, with about 60 average polluted days per year; moreover, cities having more than 100 days of air pollution (exceeding the limits set for PM10), they have a very high average number of infected people (about 3350 infected individuals, 7th April 2020), whereas cities having less than 100 days of air pollution per year, they have a lower average number of infected people (about 1014 individuals). The findings here also suggest that to minimize the impact of future epidemics similar to COVID-19, the max number of days per year that Italian provincial capitals or similar industrialized cities can exceed the limits set for PM10 or for ozone, considering their meteorological conditions, is about 48 days. Moreover, results here reveal that the explanatory variable of air pollution in cities seems to be a more important predictor in the initial phase of diffusion of viral infectivity (on 17th March 2020, b1 = 1.27, p < 0.001) than interpersonal contacts (b2 = 0.31, p < 0.05). In the second phase of maturity of the transmission dynamics of COVID-19, air pollution reduces intensity (on 7th April 2020 with b′1 = 0.81, p < 0.001) also because of the indirect effect of lockdown, whereas regression coefficient of transmission based on interpersonal contacts has a stable level (b′2 = 0.31, p < 0.01). This result reveals that accelerated transmission dynamics of COVID-19 is due to mainly to the mechanism of “air pollution-to-human transmission” (airborne viral infectivity) rather than “human-to-human transmission”. Overall, then, transmission dynamics of viral infectivity, such as COVID-19, is due to systemic causes: general factors that are the same for all regions (e.g., biological characteristics of virus, incubation period, etc.) and specific factors which are different for each region and/or city (e.g., complex interaction between air pollution, meteorological conditions and biological characteristics of viral infectivity) and health level of individuals (habits, immune system, age, sex, etc.). Lessons learned for COVID-19 in the case study here suggest that a proactive strategy to cope with future epidemics is also to apply especially an environmental and sustainable policy based on reduction of levels of air pollution mainly in hinterland and polluting cities- (having low wind speed, high percentage of moisture and number of fog days) -that seem to have an environment that foster a fast transmission dynamics of viral infectivity in society. Hence, in the presence of polluting industrialization in regions that can trigger the mechanism of air pollution-to-human transmission dynamics of viral infectivity, this study must conclude that a comprehensive strategy to prevent future epidemics similar to COVID-19 has to be also designed in environmental and socioeconomic terms, that is also based on sustainability science and environmental science, and not only in terms of biology, medicine, healthcare and health sector.

Keywords: Coronavirus Infection, COVID-19, Virus Pneumonia, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, SARS Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, Pandemic, Epidemic Outbreak, Transmission Dynamics, Disease Transmission, Air Pollution, Particulate Matter, Infection Prevention, Quarantine, Airborne disease, Airborne Transmission, Virus Transmission, Lung Disease, Opportunistic pathogen, Viral infectivity

Graphical abstract

This result reveals that transmission dynamics of COVID-19 is due to two mechanisms given by: human-to-human transmission (measured with density of population) and air pollution-to-human transmission (airborne viral infectivity); in polluting citieswith low wind speed, the accelerated diffusion of viral infectivity is also due to mechanism of air pollution-to-human transmission that may be stronger than human-to-human transmission.

Highlights

-

•

Transmission dynamics of COVID-19 is due to air pollution-to-human transmission rather than human-to-human transmission

-

•

Cities with more than 100 days of air pollution have a very high average number of infected individuals

-

•

Transmission dynamics of COVID-19 has a high association with air pollution of cities in the presence of low wind speed

-

•

Polluting cities in hinterland with low speed of wind have a high number of infected individuals than coastal cities

-

•

A strategy to prevent future epidemics has also to be based on sustainability science and environmental science

1. The problem and goals of this investigation

This study has two goals. The first is to explain the main factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 that is generating a high level of deaths worldwide. The second is to suggest a strategy to cope with future epidemic threats similar to COVID-19 having an accelerated viral infectivity in society.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a viral infection that generates a severe acute respiratory syndrome with serious clinical symptoms given by fever, dry cough, dyspnea, respiratory disorders and pneumonia and may result in progressive respiratory failure and death. Kucharski et al. (2020) argue that COVID-19 transmission declined in Wuhan (China) during late January 2020 (WHO, 2019, WHO, 2020, WHO, 2020a; nCoV-2019 Data Working Group, 2020). However, as more infected individuals arrived in international locations before control measures are applied, numerous epidemic chains have led to new outbreaks in different nations (Xu and Kraemer Moritz, 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). An outbreak of COVID-19 has led to more than 26,640 confirmed deaths in Italy and more than 206,560 deaths worldwide as of April 27, 2020 (Johns Hopkins Center for System Science and Engineering, 2020; cf., Dong et al., 2020). The prime factors of transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in Italy, having a very high number of deaths, are crucial elements for explaining possible relationships underlying the temporal and spatial aspects of the diffusion of this viral infectivity worldwide. Results here are basic to design a strategy to prevent future epidemics similar to COVID-19 that generates health and socioeconomic issues for nations and globally (EIU, 2020a).

Currently, as people with the COVID-19 infection can arrive in countries or regions with low ongoing transmission, efforts should be done to stop disease transmission, prevent potential outbreaks and to avoid second and other subsequent epidemic waves of COVID-19 (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2020; Quilty et al., 2020). Wells et al. (2020) argue that at the very early stage of the epidemic, reduction in the rate of exportation could delay the importation of cases into cities or nations unaffected or with low number of cases of COVID-19, to gain time to coordinate an appropriate public health response. After that, rapid contact tracing is basic within the epicenter and within and between importation cities to limit human-to-human transmission outside of outbreak cities or countries, also applying appropriate isolation of cases (Wells et al., 2020). For instance, the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in 2003 started in southern China was able to be controlled through tracing contacts of cases because the majority of transmission occurred after symptom onset (Glasser et al., 2011). These interventions also play a critical role in response to outbreaks where onset of symptoms and infectiousness are concurrent, such as Ebola virus disease (WHO, 2020b; Swanson et al., 2018), MERS (Public Health England, 2019; Kang et al., 2016) and other viral diseases (Hoang et al., 2019; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control., 2020a). Kucharski et al. (2020) claim that the isolation of cases and contact tracing can be less effective for COVID-19 because infectiousness starts before the onset of symptoms (cf., Fraser et al., 2004; Peak et al., 2017). Hellewell et al. (2020) show that effective contact tracing and case isolation are enough to control a new outbreak of COVID-19 within three months, but the probability of control decreases with long delays from symptom onset to isolation that increase transmission before symptoms. In the presence of COVID-19 outbreaks, it is crucial to explain the determinants of the transmission dynamics of this infectious disease for designing strategies to stop or reduce diffusion, empowering health policy with economic, social and environmental interventions. This study focuses on statistical analyses of association between infected people and environmental, demographic and geographical factors that can explain the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 over time, and provide insights to apply appropriate measures of infection control (cf., Camacho et al., 2015; Funk et al., 2017; Riley et al., 2003). In particular, this study here can explain, whenever possible, factors determining the accelerated viral infectivity in specific regions to guide policymakers to prevent future epidemics similar to COVID-19 (Cooper et al., 2006; Kucharski et al., 2015). However, there are several challenges to such study, particularly in real time. Sources may be biased, incomplete, or only capture certain temporal and spatial aspects of on-going outbreak dynamics.

2. Materials and methods

The complex problem of viral infectivity of COVID-19 is analyzed here in a perspective of reductionist approach, considering the geo-environmental and demographic factors of cities to explain the relationships supporting the transmission dynamics of this viral infectivity (cf., Linstone, 1999). In particular, this study focuses on causes of the diffusion of COVID-19 among Italian province capitals. The investigation of the causes of the accelerated diffusion of Coronavirus infection is done with a philosophical approach sensu the scholar Vico1 (Flint, 1884). The method of inquiry here is also based on Kantian approach in which theoretical framework and empirical data complement each other and are inseparable. In this case, the truth on this phenomenon under study, i.e., transmission dynamics of COVID-19, is a result of synthesis (Churchman, 1971).

2.1. Data and their sources

This study focuses on N = 55 Italian cities that are provincial capitals. Sources of data are The Ministry of Health in Italy for epidemiological data (Ministero della Salute, 2020), Legambiente (2019) for data of air pollution deriving from the Regional Agencies for Environmental Protection in Italy, il Meteo (2020) for data of weather trend in 2020 (February and March) based on information of meteorological stations of Italian province capitals, finally the Italian National Institute of Statistics for data of the density of population concerning cities under study (ISTAT, 2020).

2.2. Measures

The unit of analysis here is Italian provincial cities. In a perspective of reductionism approach for statistical analysis and decision making, this study focuses on following measures.

-

▪

Pollution. Total days exceeding the limits set for PM10 (particulate matter 10 μm or less in diameter) or for ozone in the 55 Italian provincial capitals over 2018 year. This measure has stability over time and the strategy of using the year 2018, before the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy, is to consider the temporal health effects of air pollution on population (Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002a, Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002b). In fact, number of days of air pollution within Italian cities is a main factor that affects both health of population and environment (Legambiente, 2019).

-

▪Diffusion of COVID-19. Number of infected individuals from 17th March 2020 to 7th April 2020 (Ministero della Salute, 2020). Infected individuals are detected with COVID-19 tests according to following criteria:

-

-Have fever or lower respiratory symptoms (cough, shortness of breath) and close contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case within the past 14 days; OR

-

-Have fever and lower respiratory symptoms (cough, shortness of breath) and a negative rapid flu test.

-

-

-

▪

Meteorological information. Average temperature in °C, Moisture %, wind speed in km/h, days of rain and fog from 1st February to 1st April 2020 (il Meteo, 2020).

-

▪

Interpersonal contact rates. A proxy of interpersonal contact here considers the density of population (individual/km2) in 2019 of Italian province capitals (ISTAT, 2020).

2.3. Data analysis and procedure

This study analyses a database of N = 55 Italian provincial capitals, considering variables in 2018–2019–2020 to explain the relationships between diffusion of COVID-19, demographic, geographical and environmental variables.

Firstly, preliminary analyses of variables are descriptive statistics based on mean (M), std. deviation (SD), skewness and kurtosis coefficients to assess the normality of distributions and, if necessary to fix the distributions of variables under study with a log-transformation.

Statistical analyses are performed categorizing Italian provincial capitals in groups as follows:

-

-

Hinterland cities

-

-

Coastal cities

Categorization in:

-

-

Cities with higher wind speed

-

-

Cities with lower wind speed

Categorization in:

-

-

Cities of North Italy

-

-

Cities of Central-South Italy

Categorization in:

-

-

Cities with >100 days per year exceeding the limits set for PM10 or for ozone

-

-

Cities with <100 days per year exceeding the limits set for PM10 or for ozone

Categorization in (2 categories):

-

-

Cities with ≤1000 inhabitant/km 2

-

-

Cities with >1000 inhabitant/km 2

Categorization in (3 categories):

-

-

Cities with ≤500 inhabitant/km 2

-

-

Cities with 500–1500 inhabitant/km 2

-

-

Cities with >1500 inhabitants/km 2

Secondly, bivariate and partial correlations verify relationships (or associations) between variables understudy, and measure the degree of association. After that, the null hypothesis (H 0) and alternative hypothesis (H 1) of the significance test for correlation is computed, considering two-tailed significance test.

Thirdly, the statistical analysis considers the relation between independent and dependent variables. In particular, the dependent variable (number of infected individuals across Italian provincial capitals) is a linear function of a single explanatory variable given by total days exceeding the limits set for PM10 or ozone across Italian province capitals. Dependent variables have a lag of 1 years in comparison with explanatory variables to consider temporal effects of air pollution predictor on environment and health of population in the presence of viral infectivity by COVID-19 in cities of Italy (N=55).

The specification of the linear relationship is a log-log model:

| (1) |

α is a constant; β = coefficient of regression; u = error term

y = dependent variable is number of infected individuals in cities

x = explanatory variable is a measure of air pollution, given by total days exceeding the limits set for PM10 or ozone in cities

This study also extends the statistical analysis with a multiple regression model to assess how different indicators can affect the diffusion of COVID-19. The specification of the linear relationship is also a log-log model as follows:

| (2) |

y = dependent variable is number of infected individuals in cities

x 1 = a measure of air pollution, given by total days exceeding the limits set for PM10 or ozone in cities

x 2 = density of cities, given by inhabitants/km2

In addition, Eq. (2) is performed using data of infected individuals at t = 17th March 2020 (i.e., in the starting phase of diffusion of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy), and at t + 23 days = 7th April 2020 (i.e., in the phase of maturity of diffusion of Coronavirus infection, during lockdown and quarantine) to assess the coefficient of two explanatory variables in the transmission dynamics of COVID-19. The estimation of Eq. (2) is performed using hierarchical multiple regression, a variant of the basic multiple regression procedure that allows to specify a fixed order of entry for variables to control for the effects of covariates and to test the effects of certain predictors independent of the influence of others. The R2 changes here are important to assess the predictive role of additional variables. The adjusted R-square and standard error of the estimates are useful as comparative measures to assess results between models. The F-test evaluates if the independent variables reliably predict the dependent variable.

Moreover, the relationship is also specified with a quadratic model as follows:

| (3) |

The goal here is to apply an optimization approach to calculate the minimum of Eq. (3) that suggests the maximum number of days that cities can exceed the limits set for PM10 or ozone. Beyond this critical estimated point, there are environmental inconsistencies of air pollution associated with meteorological conditions that can trigger a take-off of viral infectivity with damages for health of population and economic system in the short and long run. In addition, the max number of days that cities can exceed the limit set for air pollution and that minimizes the number of infected individuals can suggest implications of proactive strategies and critical decisions of crisis management to cope with future epidemics similar to COVID-19 in society.

Finally, if y t is number of infected individuals referred to a specific day, and Eq. (1) is calculated for each day changing dependent variable by using data of infected individuals at day t = 1, day t = 2, day t = 3, …, day t = n, the variation of coefficients of regression bi (i = 1, .., n), during quarantine and lockdown in Italy, can be used to assess with a good approximation the possible end of epidemic wave as follows:

…

Average reduction is

Decreasing bi at day 1, day-by-day, of the constant value , the i-th day when bi is close to 0 (zero), it suggests with a good approximation the ending tail of epidemic wave, ceteris paribus (meaning "other things equal") quarantine and lockdown. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method is applied for estimating the unknown parameters in linear regression models [1–3]. Statistical analyses are performed with the Statistics Software SPSS® version 24.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics of variables in log scale, based on Italian province capitals (N = 55), indicate normal distributions that are appropriate to apply parametric analyses.

Table 1 shows that hinterland cities have a average higher level of infected individuals than coastal cities. Hinterland cities have also a higher level of air pollution (average days per year) than coastal cities, in a meteorological context of lower average temperature, lower average wind speed, lower number of rain days and lower level of moisture % than coastal cities (in February-March, 2020).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of Hinterland and Coastal Italian province capitals.

| Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

Infected 17th March 2020 |

Infected 7th April 2020 |

Density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

Temp °C Feb–Mar 2020 |

Moisture % Feb–Mar 2020 |

Wind km/h Feb–Mar 2020 |

Rain days Feb–Mar 2020 |

Fog days Feb–Mar 2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinterland cities N = 45 | |||||||||

| Mean | 80.40 | 497.00 | 2201.44 | 1480.11 | 9.11 | 68.31 | 8.02 | 4.81 | 4.14 |

| Std. Deviation | 41.66 | 767.19 | 2568.34 | 1524.25 | 2.20 | 7.68 | 3.69 | 2.38 | 3.13 |

| Coastal cities N = 10 | |||||||||

| Mean | 59.40 | 171.30 | 944.70 | 1332.80 | 10.61 | 74.40 | 11.73 | 5.10 | 3.25 |

| Std. Deviation | 38.61 | 164.96 | 718.17 | 2463.04 | 2.20 | 7.38 | 2.60 | 2.71 | 3.68 |

Table 2 shows that cities with low wind speed (7.3 km/h) have also an average higher level of infected individuals than cities having higher wind speed (average of 12.77 km/h in February-March, 2020). Cities with lower intensity of wind speed have also a higher level of air pollution (average days per year), in a meteorological context of lower average temperature, less rain days, lower level of moisture % and higher average number of days of fog.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of cities with higher or lower wind speed.

| Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

Infected 17th March 2020 |

Infected 7th April 2020 |

Density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

Temp °C Feb–Mar 2020 |

Moisture % Feb–Mar 2020 |

Wind km/h Feb–Mar 2020 |

Rain days Feb–Mar 2020 |

Fog days Feb–Mar 2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities with lower wind speed N = 41 | |||||||||

| Mean | 84.32 | 536.20 | 2383.66 | 1517.41 | 9.05 | 68.23 | 7.30 | 4.56 | 4.18 |

| Std. Deviation | 43.31 | 792.84 | 2624.03 | 1569.70 | 2.12 | 7.50 | 2.77 | 2.33 | 2.94 |

| Cities with higher wind speed N = 14 | |||||||||

| Mean | 53.93 | 149.57 | 770.14 | 1265.64 | 10.36 | 72.89 | 12.77 | 5.75 | 3.39 |

| Std. Deviation | 25.87 | 153.55 | 633.21 | 2108.31 | 2.43 | 8.37 | 3.46 | 2.56 | 4.00 |

Table 3 shows that cities in the central and southern part of Italy have a lower number of infected individuals than cities in North Italy. This result is in an environment with lower level of air pollution (average days per year), higher average temperature, higher average intensity of wind speed, higher number of rain days and lower level of moisture %.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of Northern and Central-Southern Italian province capitals.

| Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

Infected 17th March 2020 |

Infected 7th April 2020 |

Density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

Temp °C Feb–Mar 2020 |

Moisture % Feb–Mar 2020 |

Wind km/h Feb–Mar 2020 |

Rain days Feb–Mar 2020 |

Fog days Feb–Mar 2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern cities N = 45 | |||||||||

| Mean | 80.51 | 515.60 | 2321.20 | 1448.00 | 9.05 | 69.40 | 7.89 | 4.80 | 4.31 |

| Std. Deviation | 42.67 | 759.18 | 2504.57 | 1538.10 | 1.97 | 7.61 | 3.15 | 2.42 | 3.06 |

| Central-Southern cities N = 10 | |||||||||

| Mean | 58.90 | 87.60 | 405.80 | 1477.30 | 10.88 | 69.50 | 12.31 | 5.15 | 2.50 |

| Std. Deviation | 32.36 | 129.98 | 444.85 | 2424.50 | 2.92 | 9.64 | 4.44 | 2.52 | 3.65 |

Table 4 confirms previous results considering cities with >100 days exceeding limits set for PM 10 or ozone: they have, versus cities with less than 100 days of air pollution, a very high level of infected individuals, in an environment with a higher average density of population, lower average intensity of wind speed, lower average temperature, higher average level of moisture % and higher number of days of fog.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of Italian provincial capitals according to days exceeding the limits set for PM10 or ozone.

| Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

Infected 17th March 2020 |

Infected 7th April 2020 |

Density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

Temp °C Feb–Mar 2020 |

Moisture % Feb–Mar 2020 |

Wind km/h Feb–Mar 2020 |

Rain days Feb–Mar 2020 |

Fog days Feb–Mar 2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities with >100 days exceeding limits set for PM10, N = 20 | |||||||||

| Mean | 125.25 | 881.70 | 3650.00 | 1981.40 | 9.19 | 71.30 | 7.67 | 4.80 | 4.88 |

| Std. Deviation | 13.40 | 1010.97 | 3238.82 | 1988.67 | 1.46 | 7.63 | 2.86 | 2.57 | 2.65 |

| Cities with <100 days exceeding limits set for PM10,N = 35 | |||||||||

| Mean | 48.77 | 184.11 | 1014.63 | 1151.57 | 9.49 | 68.34 | 9.28 | 4.90 | 3.47 |

| Std. Deviation | 21.37 | 202.76 | 768.91 | 1466.28 | 2.62 | 7.99 | 4.15 | 2.37 | 3.44 |

Table 5, Table 6 show results considering the categorization of cities per density of population (individuals/km2). Results reveal that average number of infected individuals increases with average density of people/km2, but with an arithmetic growth, in comparison to geometric growth of the number of infected individuals with other proposed categorizations of cities. These findings suggest that density of population per km2 is important for transmission dynamics but other factors may support the acceleration of viral infectivity by COVID-19 in association with higher probability of interpersonal contacts in cities having high population density.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of Italian provincial capitals according to density per km2 (2 categories).

| Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

Infected 17th March 2020 |

Infected 7th April 2020 |

Density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

Temp °C Feb–Mar 2020 |

Moisture % Feb–Mar 2020 |

Wind km/h Feb–Mar 2020 |

Rain days Feb–Mar 2020 |

Fog days Feb–Mar 2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities with ≤ 1000 inhabitant/km2N = 30 | |||||||||

| Mean | 64.37 | 248.37 | 1144.20 | 510.77 | 10.01 | 69.61 | 9.28 | 4.08 | 3.75 |

| Std. Deviation | 39.25 | 386.95 | 1065.99 | 282.11 | 1.95 | 10.30 | 4.41 | 2.37 | 3.40 |

| Cities with > 1000 inhabitant/km2N = 25 | |||||||||

| Mean | 91.24 | 665.08 | 2967.44 | 2584.40 | 8.63 | 69.19 | 7.99 | 5.80 | 4.26 |

| Std. Deviation | 40.24 | 919.70 | 3092.46 | 2000.63 | 2.40 | 3.59 | 2.79 | 2.17 | 3.03 |

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of Italian provincial capitals according to density per km2 (3 categories).

| Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

Infected 17th March 2020 |

Infected 7th April 2020 |

Density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

Temp °C Feb–Mar 2020 |

Moisture % Feb–Mar 2020 |

Wind km/h Feb–Mar 2020 |

Rain days Feb–Mar 2020 |

Fog days Feb–Mar 2020 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities with <500 inhabitant/km2N = 17 | |||||||||

| Mean | 52.82 | 116.12 | 695.35 | 312.76 | 9.88 | 71.12 | 9.52 | 4.44 | 4.41 |

| Std. Deviation | 36.87 | 128.13 | 570.58 | 161.34 | 2.12 | 8.91 | 5.73 | 2.79 | 3.79 |

| Cities with 500–1500 inhabitant/km2N = 22 | |||||||||

| Mean | 84.32 | 430.91 | 1775.73 | 951.32 | 9.04 | 68.50 | 8.37 | 4.34 | 3.75 |

| Std. Deviation | 37.28 | 476.29 | 1122.02 | 277.77 | 2.65 | 9.17 | 2.33 | 2.06 | 2.99 |

| Cities with >1500 inhabitant/km2N = 16 | |||||||||

| Mean | 91.19 | 789.00 | 3601.56 | 3355.44 | 9.33 | 68.86 | 8.26 | 6.03 | 3.84 |

| Std. Deviation | 43.29 | 1103.03 | 3697.89 | 2151.27 | 1.81 | 4.32 | 2.79 | 2.19 | 3.03 |

In short, results suggest that among Italian province capitals, the number of infected people is higher in: cities with >100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone, located in hinterland zones, having a low wind speed and lower temperature in °C.

Table 7 shows the association between variables of infected individuals on 17th March and 7th April 2020, and other variables: a correlation higher than 60% (p-value < 0.001) is between air pollution and infected individuals, a lower coefficient of correlation is between density of population and infected individuals (r = 48–53%, p-value < 0.001). Results also show a negative correlation between number of infected individuals and intensity of wind speed (r = −38% and −31%, p-value < 0.05 on 17th March and 7th April 2020 respectively): in fact, wind speed cleans air from pollutants that are associated with possible transmission dynamics of viral infectivity (COVID-19) as it will be explained later.

Table 7.

Correlation.

| N = 55 |

Log Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

Log Density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

Temp °C Feb–Mar 2020 |

Moisture % Feb–Mar 2020 |

Wind km/h Feb–Mar 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log infected 17th March 2020 | |||||

| Pearson correlation | 0.643⁎⁎ | 0.484⁎⁎ | −0.117 | 0.005 | −0.377⁎⁎ |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.397 | 0.970 | 0.005 |

| N = 55 | Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

Density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

Temp °C Feb–Mar 2020 |

Moisture % Feb–Mar 2020 |

Wind km/h Feb–Mar 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log infected 7th April, 2020 | |||||

| Pearson correlation | 0.604⁎⁎⁎ | 0.533⁎⁎ | −0.259 | 0.026 | −0.310⁎ |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.056 | 0.853 | 0.021 |

Note:

Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Table 8 confirms high correlation between air pollution and infected individuals on 17th March and 7th April 2020, controlling meteorological factors of cities under study (r > 59%, p-value < 0.001).

Table 8.

Partial correlation.

| Control Variables Temp °C Moisture % Wind km/h Feb–Mar 2020 |

Pearson correlation | Log infected 17th March 2020 |

Log infected 7th April 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Log days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

0.607 | 0.586 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| N | 50 | 50 |

Partial correlation in Table 9 suggests that controlling density of population on 17th March and 7th April 2020, number of infected people is associated with air pollution (r ≥ 48%, p-value < 0.001), whereas controlling air pollution, the correlation between density of population in cities and infected individuals is lower (r = 28–36%). The reduction of coefficients of correlation (r) between infected individuals and air pollution from 17th March to 7th April 2020, and the increase of the association between infected people and density of people in cities over the same time period, controlling mutual variables, suggest that air pollution in cities seems to be a important factor in the initial phase of transmission dynamics of COVID-19 (i.e., 17th March 2020). In the phase of the maturity of transmission dynamics (7th April 2020), with lockdown that reduces air pollution, the mechanism of air pollution-to-human transmission of Coronavirus infection (airborne viral infectivity) reduces intensity, whereas coefficient of human-to-human transmission increases.

Table 9.

Partial Correlation.

| Control variables Log density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

Pearson correlation |

Log infected 17th March 2020 |

Log infected 7th April 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Log days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

0.542 | 0.479 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| N | 52 | 52 | |

| Control variables Log days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone 2018 |

Pearson correlation |

Log infected 17th March 2020 |

Log infected 7th April, 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Log density inhabitants/km2 2019 |

0.279 | 0.362 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.041 | 0.007 | |

| N | 50 | 50 |

These findings are confirmed with hierarchical regression that also reveals how air pollution in cities seems to be a driving factor of transmission dynamics in the initial phase of diffusion of COVID-19 (17th March 2020). In the phase of the maturity of transmission dynamics of COVID-19 (7th April 2020), the determinant of air pollution is important to support the diffusion of viral infectivity of this airborne disease but it reduces the intensity, whereas the factor of human-to-human transmission increases, ceteris paribus (Table 10 ). This result reveals that transmission dynamics of COVID-19 is due to human-to-human transmission but the factor of air pollution-to-human transmission of viral infectivity supports a substantial growth of spatial diffusion of vital infectivity.

Table 10.

Parametric estimates of the relationship of Log Infected 17 March and 7th April 2020 on Log Days exceeding limits set for PM10 and Log Density inhabitants/km2 2019 (hierarchical regression).

| Model 1A Step 1: Air pollution |

Model 2A Step 2: Air pollution and Interpersonal contacts |

Model 1B Step 1: Air pollution |

Model 2B Step 2: Air pollution and Interpersonal contacts |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log days exceeding limits set for PM10, 2018 | Log days exceeding limits set for PM10, 2018 | Log density inhabitants/km2 2019 | Log days exceeding limits set for PM10, 2018 | Log days exceeding limits set for PM10, 2018 | Log density inhabitants/km2 2019 | ||

|

Log infected 17th March 2020 |

Log infected 7th April, 2020 |

||||||

| Constant α (St. Err.) |

−1.168 (1.053) |

−2.168 (1.127) |

Constant α (St. Err.) |

2.552⁎⁎ (0.822) |

1.538 (0.854) |

||

| Coefficient β 1 (St. Err.) |

1.526⁎⁎⁎ (0.250) |

1.266⁎⁎⁎ (0.272) |

Coefficient β 1 (St. Err.) |

1.077⁎⁎⁎ (0.195) |

0.813⁎⁎⁎ (0.206) |

||

| Coefficient β 2 (St. Err.) |

0.309⁎ (0.148) |

Coefficient β 2 (St. Err.) |

0.314⁎⁎ (0.111) |

||||

| F | 37.342⁎⁎⁎b | 22.059⁎⁎⁎c | F | 30.480⁎⁎⁎b | 21.130⁎⁎⁎c | ||

| R2 | 0.413 | 0.459 | R2 | 0.365 | 0.448 | ||

| ΔR2 | 0.413 | 0.046 | ΔR2 | 0.385 | 0.083 | ||

| ΔF | 37.342⁎⁎⁎ | 4.388⁎ | ΔF | 30.480⁎⁎⁎ | 7.843⁎⁎ | ||

b = predictors: Log Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone in 2018

c = predictors: Log Days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone in 2018 year; Log Density inhabitants/km2 in 2019.

p-Value < 0.001.

p-Value < 0.01.

p-Value < 0.05.

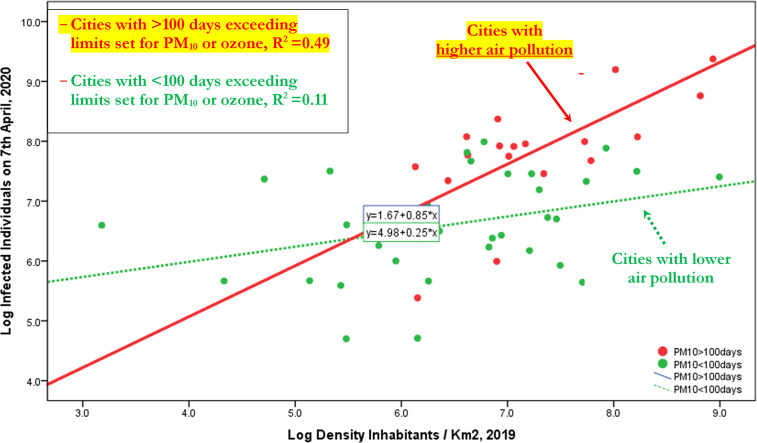

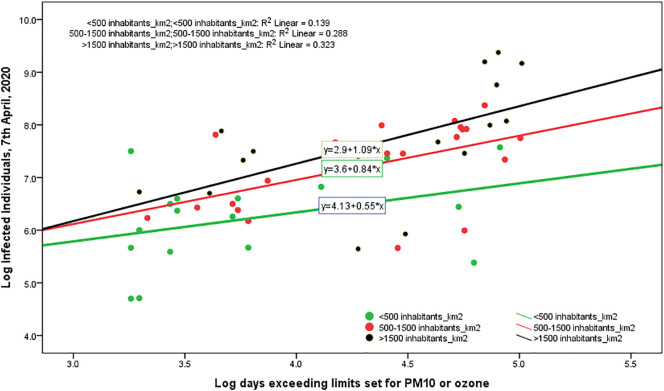

Table 11 shows results of the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 considering the interpersonal contacts, measured with density of population in cities understudy. In short, results suggest that density of population explains the number of infected individuals, increasing the probability of human-to-human transmission. However, if we decompose the sample in the cities with ≤100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone and cities with >100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone, then the expected increase of number of infected individuals is higher in cities having more than 100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone per year. In particular,

-

○

Cities with ≤100 days exceeding limits set for PM10, an increase of 1% in density of population, it increases the expected number of infected individuals by about 0.25%

-

○

Cities with >100 days exceeding limits set for PM10, an increase of 1% in density of population, it increases the expected number of infected individuals by about 85%!

Table 11.

Parametric estimates of the relationship of Log Infected 7th April 2020 on Log Density inhabitants/km2 2019, considering the groups of cities with days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone.

| ↓Dependent variable | Model of cities with <100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone, 2018 |

↓Dependent variable | Model of cities with >100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone, 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log density inhabitants/km2 2019 | Log density inhabitants/km2 2019 | ||

|

Log infected 7th April, 2020 |

Log infected 7th April, 2020 |

||

| Constant α (St. Err.) |

4.976 (0.786) |

Constant α (St. Err.) |

1.670 (1.491) |

| Coefficient β 1 (St. Err.) |

0.252⁎ (0.120) |

Coefficient β 1 (St. Err.) |

0.849⁎⁎⁎ (0.205) |

| R2 (St. Err. of Estimate) | 0.119 (0.812) | R2 (St. Err. of Estimate) | 0.488(0.738) |

| F | 4.457⁎ | F | 17.168⁎⁎⁎ |

Note: Explanatory variable: Log Density inhabitants/km2 in 2019.

p-Value < 0.001.

p-Value < 0.05.

The statistical output of Table 11 is schematically summarized as follows:

| Cities with ≤100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone | Cities with >100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone | |

|---|---|---|

| Density of population (coefficient of regression β1) | 0.25 (p < 0.05) | 0.85 (p < 0.001) |

| F | 4.457 (p < 0.05) | 17.168 (p < 0.001) |

| R2 | 11.9% | 49% |

Fig. 1 confirms, ictu oculi (in the blink of an eye), that the coefficient of regression in cities with >100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone is much bigger than coefficient in cities with ≤100 days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone, suggesting that the mechanism of air pollution-to-human transmission is definitely important to explain the transmission dynamics of COVID-19. Fig. 1A in Appendix confirms this result that viral infectivity of COVID-19 increases with the mechanism of air pollution-to-human transmission (airborne viral infectivity), but the rate of growth of viral infectivity is also supported by a high density of population that sustains the mechanism of human-to-human transmission. The policy implications here are clear: COVID-19 has reduced transmission dynamics on population in the presence of lower level of air pollution and specific environments based on a higher wind speed (e.g., in South Italy). Hence, the effect of accelerated transmission dynamics of COVID-19 cannot be explained without accounting for the level of air pollution and other geo-environmental conditions of the cities, such as high wind speed and temperature.

Fig. 1.

Regression line of Log Infected individuals 7th April, 2020 on Log Density inhabitants/km2 2019, considering the groups of cities with days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone <, or ≥100 days.

Note: This result reveals that transmission dynamics of COVID-19 is due to two mechanisms given by: human-to-human transmission (based on density of population) and air pollution-to-human transmission (airborne viral infectivity); in particular, in polluting cities, the accelerated diffusion of viral infectivity is also due to mechanism of air pollution-to-human transmission that may have a stronger effect than human-to-human transmission!

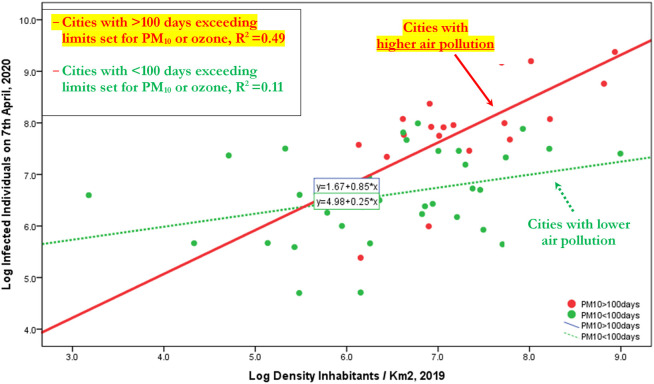

A main question for supporting a strategy to prevent future epidemics similar to COVID-19 is: What is the maximum number of days that cities can exceed the limits set for PM10 or ozone per year, before that the combination between air pollution and meteorological conditions triggers a take-off of viral infectivity (epidemic diffusion) with damages for health of population, economy and society?

The function based on Table 12 is:

Table 12.

Parametric estimates of the relationship of Infected individuals 7th April 2020 on days exceeding limits set for PM10 or ozone (regression analysis, quadratic model).

| Response variable: infected individuals 7th April 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory variable | B | St. Err. | R2 (St. Err. of the Estimate) | F (sign.) |

| - Days exceeding limits set for PM10 | −46.221 | 36.06 | 0.37 (1893.27) | 16.94 (0.001) |

| - (Days exceeding limits set for PM10) 2 | 0.485⁎ | 0.217 | ||

| Constant | 1844.216 | 1208.11 | ||

Note:

p-Value = 0.030 < 5%.

y = number of infected individuals on 7th April 2020

x = days exceeding limits of PM10 or ozone in Italian provincial capitals

The minimization of this function is performed imposing first derivative (y') equal to zero (0):

x = 46.221/0.97 = 47.65, i.e., 48 days exceeding limits of PM10 or ozone in Italian provincial capitals

This finding suggests that the max number of days that Italian provincial capitals can exceed per year the limits set for PM10 (particulate matter 10 μm or less in diameter) or for ozone, considering the meteorological conditions, is about 48 days (Fig. 2 ). Beyond this critical point, the analytical and geometrical output suggests that environmental inconsistencies, because of the combination between air pollution and meteorological conditions, trigger a take-off of viral infectivity (epidemic diffusion) with damages for health of population, economy and society.

Fig. 2.

Estimated relationship of number of infected on days exceeding limits of PM10 in Italian provincial capitals (Quadratic model).

Finally, the reduction of unstandardized coefficient of regression in Table 13 , from 17th March to 7th April 2020, suggests a deceleration of the diffusion of COVID-19 over time and space. The question is: how many days are necessary to stop the epidemic, ceteris paribus (quarantine and lockdown)?

Table 13.

Coefficient of regression of the linear model per day based on Eq. (1) and daily change.

| Day | Unstandardized coefficient B | Standard Error | Sign. | R2 | Δ = Bi − B(i − 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17th March, 2020 | 1.526 | 0.250 | 0.001 | 0.400 | |

| 19 | 1.362 | 0.238 | 0.001 | 0.370 | −0.1640 |

| 21 | 1.360 | 0.234 | 0.001 | 0.377 | −0.0020 |

| 22 | 1.340 | 0.232 | 0.001 | 0.375 | −0.0200 |

| 23 | 1.322 | 0.231 | 0.001 | 0.370 | −0.0180 |

| 24 | 1.320 | 0.228 | 0.001 | 0.376 | −0.0020 |

| 25 | 1.285 | 0.227 | 0.001 | 0.364 | −0.0350 |

| 26 | 1.287 | 0.223 | 0.001 | 0.375 | +0.0020 |

| 27 | 1.291 | 0.221 | 0.001 | 0.380 | +0.0040 |

| 28 | 1.289 | 0.202 | 0.001 | 0.424 | −0.0020 |

| 29 | 1.246 | 0.216 | 0.001 | 0.375 | −0.0430 |

| 30 | 1.236 | 0.209 | 0.001 | 0.386 | −0.0100 |

| 31 | 1.143 | 0.198 | 0.001 | 0.375 | −0.0930 |

| 1st April, 2020 | 1.162 | 0.201 | 0.001 | 0.376 | +0.0190 |

| 2 | 1.129 | 0.196 | 0.001 | 0.373 | −0.0330 |

| 3 | 1.127 | 0.194 | 0.001 | 0.377 | −0.0020 |

| 4 | 1.076 | 0.194 | 0.001 | 0.355 | −0.0510 |

| 5 | 0.982 | 0.192 | 0.001 | 0.317 | −0.0940 |

| 6 | 1.074 | 0.191 | 0.001 | 0.361 | +0.0920 |

| 7 | 1.077 | 0.195 | 0.001 | 35.300 | +0.0030 |

| Arithmetic mean Δ = δ= | −0.0236 |

Let, the average reduction of the coefficients of regression Bi at 7th April 2020 equal to δ = −0.0236, let the coefficient B at 7th April 2020 equal to 1.077, the date when B is close to 0 (zero) in Italy, with a constant reduction day by day of the value δ from 7th April 2020 onwards, is about 22 May 2020 or thereabouts (this date is a good approximation of when the coefficient B may be lower than 0.05, suggesting a very low number of infected individuals in Italy).

4. Phenomena explained: the accelerated diffusion of COVID-19

Considering the results just mentioned, the fundamental questions are:

Why did this Coronavirus infection spread so rapidly in Italy (and other countries)?

How is the link between geographical and environmental factors and accelerated diffusion of COVID-19 in specific regions?

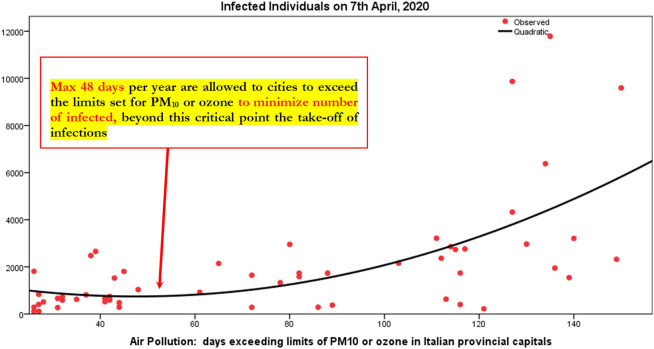

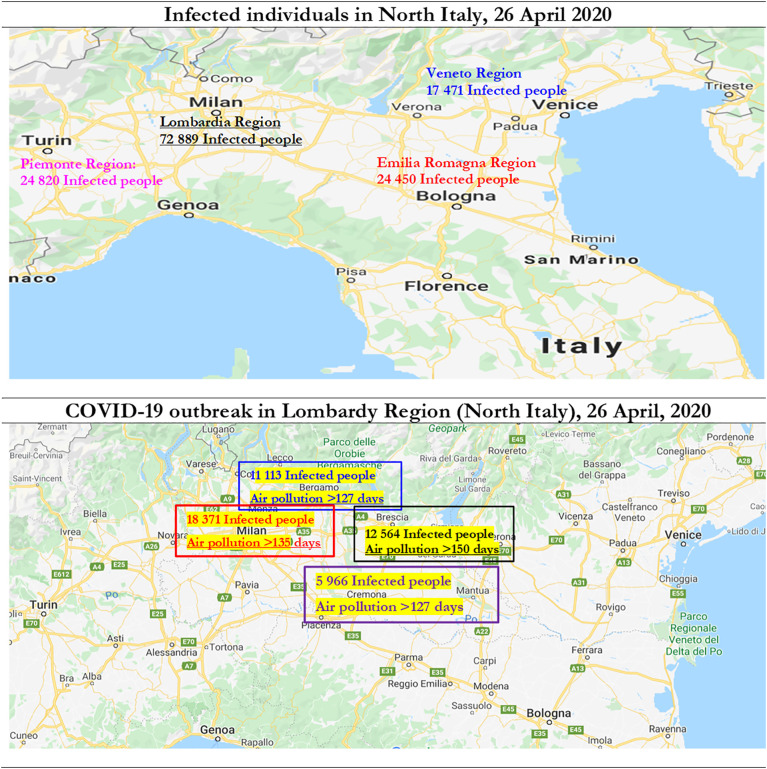

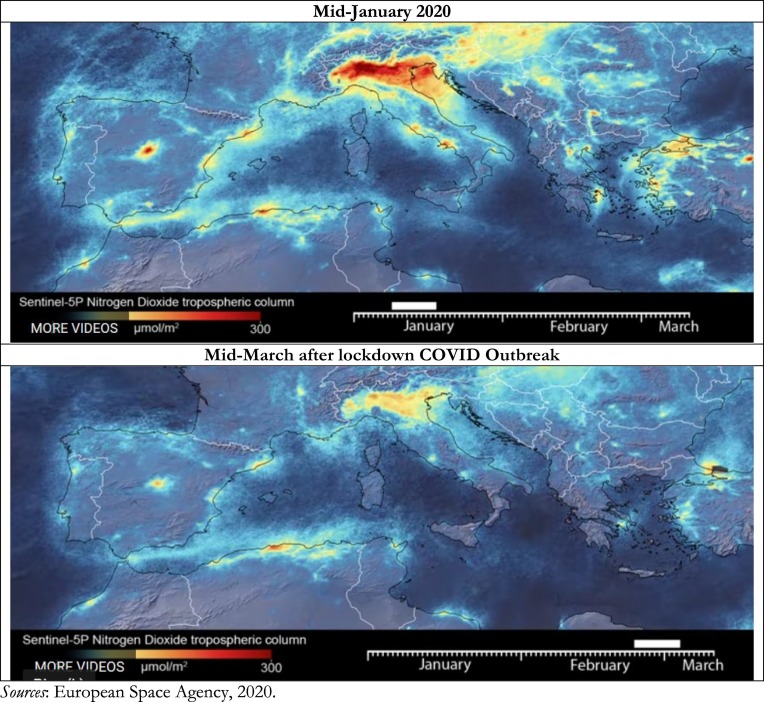

Fig. 3 shows COVID-19 outbreak in North Italy with number of infected individuals and days exceeding the limits set for PM10 or for ozone. Statistical analyses here for N = 55 Italian provincial capitals confirm the significant association between high diffusion of viral infectivity of Coronavirus Disease 2019 and air pollution. Studies show that the diffusion of viral infectivity depends on the interplay between host factors and environment (Neu and Mainou, 2020; Morawska and Cao, 2020). In this context, it is critical to explain how air quality can affect viral dissemination at national and global level (Das and Horton, 2017). Many ecological studies have examined the association between the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease, respiratory virus circulation and various climatic factors (McCullers, 2006; Jansen et al., 2008). These studies show that in temperate climates, the epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease has a peak of incidence in winter months (Dowell et al., 2003; Kim et al., 1996; Talbot et al., 2005).

Fig. 3.

COVID-19 Outbreak (number of infected individual on 26 April 2020) and days exceeding the limits set for PM10 or ozone.

Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002a, Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002b argue that, in addition to climate factors, the health effects of air pollution have been subject to intense investigations in recent years. Air pollution is ubiquitous in manifold urban areas of developed and developing nations. Air pollution has gaseous components and particulate matter (PM). The former includes ozone (O3), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), carbon monoxide (CO) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) that generate inflammatory stimuli on the respiratory tract of individuals (Glencross et al., 2020). PM has a complex composition that includes metals, elemental carbon and organic carbon (both in hydrocarbons and peptides), sulphates and nitrates, etc. (Ghio et al., 2012; Wooding et al., 2019).

Advanced countries, such as in Europe, have more and more smog because of an unexpected temperature inversion, which traps polluting emissions from the city near ground-level mainly in winter season. The ambient pollution mixes with moisture in the air to form a thick fog that affects the health of people in the city (Wang et al., 2016; Bell et al., 2004). The exposure to pollutants, such as airborne particulate matter and ozone, generates respiratory and cardiovascular diseases with increases in mortality and hospital admissions (cf., Langrish and Mills, 2014). Wei et al. (2020) analyze the effect of heavy aerosol pollution in northern China-(characterized by high PM2.5 concentrations in a wide geographical area)- that impacts on environmental ecology, climate change and public health (cf., Liu et al., 2017, Liu et al., 2018; Jin et al., 2017). The biological components of air pollutants and bio aerosols also include bacteria, viruses, pollens, fungi, and animal/plant fragments (Després et al., 2012; Fröohlich-Nowoisky et al., 2016; Smets et al., 2016). Studies show that during heavy aerosol pollution in Beijing (China), 50%–70% of bacterial aerosols are in sub micrometer particles, 0.56–1 mm (T. Zhang et al., 2019; cf., Zhang et al., 2016). As bacteria size typically ranges from 0.5 to 2.0 mm (Després et al., 2012), they can form clumps or attach to particles and transport regionally between terrestrial, aquatic, atmospheric and artificial ecosystems (Smets et al., 2016). Moreover, because of regional bio aerosol transportation, harmful microbial components and bacterial aerosols have dangerous implications on human health and also plantation (cf., Van Leuken et al., 2016). Harmful bio aerosol components (including pathogens, antibiotic-resistant bacteria and endotoxins) can cause severe respiratory and cardiovascular diseases in society (Charmi et al., 2018). In fact, the concentration of microbes, pathogens and toxic components significantly increases during polluted days, compared to no polluted days (Liu et al., 2018). In addition, airborne bacterial community structure changes with pollutant concentration, which may be related to bacterial sources and multiplication in the air (T. Zhang et al., 2019). Studies also indicate that microbial community composition and bioactivity are significantly affected by particle concentration (Liu et al., 2018). To put it differently, the atmospheric particulate matter harbors more microbes during polluted days than sunny or clean days (Wei et al., 2016). These studies can explain one of the driving factors of higher diffusion of COVID-19 in the industrialized regions of Nord Italy, rather than in other part of Italy (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6). In fact, viable bio aerosol particles and high microbial concentration in particulate matter play their non-negligible role during air pollution and transmission dynamics of viral infectivity (T. Zhang et al., 2019; Morawska and Cao, 2020). For instance, studies on airborne bacteria in PM2.5 from the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei regions in China reveal that air pollutants are main factors in shaping bacterial community structure (Gao et al., 2017). Xie et al. (2018) indicate that total bacteria concentration is higher in moderately polluted air rather than in clean or heavily polluted air. Liu et al. (2018) argue that bacterial concentration is low in heavily pollution of PM2.5 and PM10, whereas the pathogenic bacteria concentration is very high in heavy and moderate pollution. Sun et al. (2018) study bacterial community during low and high particulate matter (PM) pollution and find out that predominant species vary with PM concentration. In general, bio aerosol concentrations are influenced by complex factors, such as emission sources, terrain, meteorological conditions and other climate factors (Zhai et al., 2018). Wei et al. (2020) investigate the differences between inland and coastal cities in China (Jinan and Weihai, respectively) to explain the influence of topography, meteorological conditions and geophysical factors on bio aerosol. Results suggest that from clean days to high polluted days, bacterial community structure is influenced by bacterial adaptation to pollutants, chemical composition of pollutants and meteorological conditions (cf., Sun et al., 2018). Moreover, certain bacteria from Proteobacteria and Deinococcus-Thermus have high tolerance towards environmental stresses and can adapt to extreme environments. As a matter of fact, bacilli can survive to harsh environments by forming spores. Moreover, certain bacteria with protective mechanisms can survive in highly polluted environments, while other bacteria cannot withstand such extreme conditions. In particular, bacteria survive in the atmosphere adapting to ultraviolet exposure, reduced nutrient availability, desiccation, extreme temperatures and other factors. In short, in the presence of accumulated airborne pollutants, more microorganisms might be attached to particulate matter. Thus, in heavy or severe air pollution, highly toxic pollutants in PM2.5 and PM10 may inhibit microbial growth. Numerous studies also indicate that the combination between meteorological conditions and air pollution creates an appropriate environment for microbial community structure and abundance, and diffusion of viral infectivity (cf., Jones and Harrison, 2004). Zhong et al. (2018) argue that static meteorological conditions may explain the increase of PM2.5. In general, bacterial communities during aerosol pollution are influenced by bacterial adaptive mechanisms, particle composition, and meteorological conditions. The particles could also act as carriers, which have complex adsorption and toxicity effects on bacteria (Wei et al., 2020). Certain particle components are also available as nutrition for bacteria and the toxic effect dominates in heavy pollution. The bacterial adaptability towards airborne pollutants can cause bacterial survival or death for different species. Groulx et al. (2018) argue that microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi in addition to other biological matter like endotoxins and spores, commingle with particulate matter air pollutants. Hence, microorganisms may be influenced by interactions with ambient particles leading to the inhibition or enhancement of viability (e.g., tolerance to variation in seasonality, temperature, humidity, etc.). Moreover, Groulx et al. (2018) claim that in the case of microbial agents of communicable disease, such as viruses, the potential interactions with pollution may have public health implications. Groulx et al. (2018, p. 1106) describe an experimental platform to investigate the implications of viral infectivity changes:

Preliminary evidence suggests that the interactions between airborne viruses and airborne fine particulate matter influence viral stability and infectivity ….. The development of a platform to study interactions between artificial bio aerosols and concentrated ambient particles provides an opportunity to investigate the direction, magnitude and mechanistic basis of these effects, and to study their health implications.… The interactions of PM2.5 with Φ6 bacteriophages decreased viral infectivity compared to treatment with HEPA2-filtered air alone; By contrast, ΦX174, a non-enveloped virus, displayed increased infectivity when treated with PM2.5 particles relative to controls treated only with HEPA-filtered air.

Thus, the variation in bacterial community structure is related to different pollution intensities. Wei et al. (2020) show that Staphylococcus increases with PM2.5 and is the most abundant bacteria in moderate pollution. In heavy or severe pollution, bacteria that are adaptable to harsh environments, increase. In moderate pollution, PM2.5 might harbor abundant bacteria, especially genera containing opportunistic pathogens. Therefore, effective measures should control health risks caused by bio aerosols during air pollution, especially for immunocompromised, such as elderly and other fragile individuals. This study may support the results here and explain the high mortality in Italy because of COVID-19 in individuals having previous respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and other disorders: in fact, the percentage of deaths compared to the total of those who tested positive for COVID-19 in Italy is of about 80% in individuals aged >70 years with comorbidities as of April 26, 2020 (Istituto Superiore Sanità, 2020; cf., WHO, 2020c). Papi et al. (2006) also indicate that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is significantly exacerbated by respiratory viral infections that cause reduction of forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1) and airway inflammation (cf., Gorse et al., 2006). Ko et al. (2007) report that the most prevalent viruses detected during acute exacerbations of COPD in Hong Kong were the influenza A virus and coronavirus. De Serres et al. (2009) also point out that the influenza virus frequently causes acute exacerbations of asthma and COPD. Moreover, the study by Wei et al. (2020) argues that air pollution in the coastal city of Weihai in China was slightly lower than the inland city of Jinan. This study supports our results that coastal cities in Italy have a lower air pollution and the diffusion of viral infectivity by COVID-19 is lower than hinterland cities having a high level of air pollution (cf., Tab. 1). Wei et al. (2020, p. 9) also suggest that different air quality strategies should be applied in inland and coastal cities: coastal cities need start bioaerosol risk alarm during moderate pollution when severe pollution occurs in inland cities.

Other studies have reported associations between air pollution and reduced lung function, increased hospital admissions, increased respiratory symptoms and high asthma medication use (Simoni et al., 2015; Jalaludin et al., 2004). In this context, the interaction between climate factors, air pollution and increased morbidity and mortality of people and children from respiratory diseases is a main health issue in society (Darrow et al., 2014). Asthma is a disease associated with exposure to traffic-related air pollution and tobacco smoking (Liao et al., 2011). Many studies show that exposure to traffic-related outdoor air pollutants (e.g., PM10 with an aerodynamic diameter ≤ 10 μm, nitrogen dioxide NO2, carbon monoxide CO, sulfur dioxide SO2, and ozone O3) increases the risk of asthma or asthma-like symptoms (Shankardass et al., 2009). Especially, high levels of PM10 increases cough, lower respiratory disorders and lower peak expiratory flow (Ward and Ayres, 2004; Nel, 2005). Weinmayr et al. (2010) provide strong evidence that PM10 may be an aggravating factor of asthma in children. Furthermore, asthma symptoms are exacerbated by air pollutants, such as diesel exhaust, PM10, NO2, SO2, O3 and respiratory virus, such as adenovirus, influenza, parainfluenza and respiratory syncytial virus (Jaspers et al., 2005; Murdoch and Jennings, 2009; Murphy et al., 2000; Wong et al., 2009). The study by Liao et al. (2011) confirms that exacerbations of asthma have been associated with bacterial and viral respiratory tract infections and air pollution. Some studies focus on the effect of meteorology and air pollution on acute viral respiratory infections and viral bronchiolitis (a disease linked to seasonal changes in respiratory viruses) in the first years of life (Nenna et al., 2017; Ségala et al., 2008; Vandini et al., 2013, Vandini et al., 2015). Carugno et al. (2018) analyze respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), the primary cause of acute lower respiratory infections in children: bronchiolitis. Results suggest that seasonal weather conditions and concentration of air pollutants seem to influence RSV-related bronchiolitis epidemics in Italian urban areas. In fact, airborne particulate matter may influence the children's immune system and foster the spread of RSV infection. This study also shows a correlation between short- and medium-term PM10 exposures and increased risk of hospitalization because of RSV bronchiolitis among infants. In short, manifold environmental factors-(such as air pollution levels, circulation of respiratory viruses and colder temperatures)-induce longer periods of time spent indoors with higher opportunities for diffusion of infections between people. In fact, high diffusion of COVID-19 in North Italy is in winter period (February–March 2020). Studies also show that air pollution is higher during winter months and it has been associated with increased hospitalizations for respiratory diseases and other disorders (Ko et al., 2007a; Medina-Ramón et al., 2006). Moreover, oscillations in temperature and humidity may lead to changes in the respiratory epithelium, which increase susceptibility to infections (Deal et al., 1980). Murdoch and Jennings (2009) correlate the incidence rate of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) with fluctuations in respiratory virus activity and environmental factors in New Zealand, showing how incidence rates of IPD are associated with the increased activity of some respiratory viruses and air pollution. Another side effect of air pollution exposure is the high incidence of mumps. In fact, Hao et al. (2019) show that exposure to NO2 and SO2 is significantly associated with higher risk of developing mumps. Instead, Yang et al. (2020) show that the exposure of people to SO2, NO2, O3, PM10 and PM2.5 is associated with hand, foot, and mouth diseases. Moreover, the effect of air pollution in the cold season is higher than in the warm season. Shepherd and Mullins (2019) analyze the relationship between arthritis diagnosis in those over 50 and exposure to extreme air pollution in utero or infancy. In particular, this study links early-life air pollution exposure to later-life arthritis diagnoses, and suggests a particularly strong link for Rheumatoid arthritis.3 Shepherd and Mullins (2019) also argue that exposure to smog and air pollution in the first year of life is associated with a higher incidence of arthritis later in life. Overall, then, these studies suggest complex relationships between people, meteorological conditions, air pollution and viral infectivity over time and space.

4.1. Air pollution, immune system and genetic damages

The composition of ambient particulate matter (PM) varies both geographically and seasonally because of the mix of sources at any location across time and space. A vast literature shows short-term effects of air pollution on health, but air pollution affects morbidity also in the long run (Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002a, Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002b). The damages of air pollution on health can be explained as follows. Air pollutants exert toxic effects on respiratory and cardiovascular systems of people; in addition, ozone, oxides of nitrogen, and suspended particulates are potent oxidants, either through direct effects on lipids and proteins or indirectly through the activation intracellular oxidant pathways (Rahman and MacNee, 2000). Studies of animal and human in-vitro and in-vivo exposure have demonstrated the powerful oxidant capacity of inhaled ozone with activation of stress signaling pathways in epithelial cells (Bayram et al., 2001) and resident alveolar inflammatory cells (Mochitate et al., 2001). Lewtas (2007) shows that exposures to combustion emissions and ambient fine particulate air pollution are associated with genetic damages. Long-term epidemiologic studies report an increased risk of all causes of mortality, cardiopulmonary mortality, and lung cancer mortality associated with higher exposures to air pollution (cf., Coccia, 2012, Coccia, 2014; Coccia and Wang, 2015). An increasing number of studies-(investigating cardiopulmonary and cardiovascular disorders)-shows potential causative agents from air pollution combustion sources.

About the respiratory activity, the adult lung inhales approximately 10–11,000 L of air per day, positioning the respiratory epithelium for exposure to high volumes of pathogenic and environmental insults. In fact, respiratory mucosa is adapted to facilitate gaseous exchange and respond to environmental insults efficiently, with minimal damage to host tissue. The respiratory mucosa consists of respiratory tract lining fluids; bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells; tissue resident immune cells, such as alveolar macrophages, dendritic cells, innate lymphoid cells and granulocytes; as well as adaptive memory T and B lymphocytes. In health, the immune system responds effectively to infections and neoplastic cells with a response tailored to the insult, but immune system must not respond harmfully to the healthy body and benign environmental influences. A well-functioning immune system is vital for a healthy body. Inadequate and excessive immune responses generate manifold pathologies, such as serious infections, metastatic malignancies and auto-immune conditions (Glencross et al., 2020). In particular, immune system consists of multiple types of immune cells that act together to generate (or fail to generate) immune responses. In this context, the relationships between ambient pollutants and immune system is vital to explain how air pollution causes diseases and respiratory disorders in the presence of Coronavirus infection. Glencross et al. (2020) show that air pollutants can affect different immune cell types, such as particle-clearing macrophages, inflammatory neutrophils, dendritic cells that orchestrate adaptive immune responses and lymphocytes that enact those responses. In general, air pollutants stimulate pro-inflammatory immune responses across multiple classes of immune cells. In particular, the association between high ambient pollution and exacerbations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is consistent with immunological mechanisms. In fact, diseases can result from inadequate responses to infectious microbes allowing fulminant infections, inappropriate/excessive immune responses to microbes (leading to more collateral damages than the microbe itself), and inappropriate immune responses to self/environment, such as likely in the case of COVID-19. Glencross et al. (2020) also discuss evidence that air pollution can cause diseases by perturbing multicellular immune responses. Studies confirm associations between elevated ambient particulate matter and worsening of lung function in patients with COPD (Bloemsma et al., 2016), between COPD exacerbations and both ambient particulate matter and ambient pollutant gasses (Li et al., 2016; Papi et al., 2006) and similarly for asthma exacerbations with high concentration of ambient pollutants (Orellano et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2015). In short, associations between ambient pollution and airways exacerbations are stronger than associations with development of chronic airways diseases. Glencross et al. (2020) argue that ambient pollutants can directly trigger cellular signaling pathways, and both cell culture studies and animal models have shown profound effects of air pollutants on every type of immune cell studied. In addition, studies suggest an action of air pollution to augment Th2 immune responses and perturb antimicrobial immune responses. This mechanism also explains the association between high air pollution and increased exacerbations of asthma – a disease characterized by an underlying Th2 immuno-pathology in the airways with severe viral-induced exacerbations. As inhaled air pollution deposits primarily on respiratory mucosa, potential strategies to reduce such effects may be based on vitamin D supplementation. Studies show that plasma levels of vitamin D, activated by ultraviolet B, are significantly higher in summer and fall than winter and spring season, in a latitude-dependent manner (Barger-Lux and Heaney, 2002). Since the temperature and hour of sun depend on latitude, Oh et al. (2010) argue that adequate activated vitamin D levels are also associated with diminished cancer risk and mortality in specific populations (Lim et al., 2006; Grant, 2002). For instance, breast cancer incidence correlates inversely with the levels of serum vitamin D and ultraviolet B exposure, which have the highest intensity in summer season. The relationships between adequate supply of vitamin D and low cancer risk are relevant to breast cancer, colon, prostate, endometrial, ovarian, and also lung cancer (Zhou et al., 2005). In the context of this study, and considering the negative effects of air pollution on human health and transmission dynamics of Coronavirus infection, summer season may have twofold effects to reduce diffusion of COVID-19:

-

1)

hot and sunny weather increases temperature and improves air circulation in environment that can reduce air pollution, and as result alleviate transmission of COVID-19 (cf., Ko et al., 2007a; Medina-Ramón et al., 2006; Wei et al., 2020; Dowell et al., 2003; Kim et al., 1996; Talbot et al., 2005);

-

2)

sunny days and summer season induce in population a higher production of vitamin D that reinforces and improves the function of immune system to cope with Coronavirus infection and other diseases (cf., Oh et al., 2010).

5. Discussion and suggested strategies to prevent future epidemics similar to COVID-19

At the end of 2019, medical professionals in Wuhan (China) were treating cases of pneumonia and respiratory disorders that had an unknown source (Li et al., 2020; Zhu and Xie, 2020; Chan et al., 2020; Backer et al., 2020). Days later, researchers confirmed that the illnesses were caused by a new coronavirus (COVID-19). By January 23, 2020, Chinese authorities had shut down transportation going into and out of Wuhan, as well as local businesses, in order to reduce the spread of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; Public Health England, 2020; Manuell and Cukor, 2011). It is the beginning of several quarantines set up in China and other countries around the world to cope with transmission dynamics of COVID-19. Quarantine is the separation and restriction of movement of people who have potentially been exposed to a contagious disease to ascertain if they become unwell, in order to reduce the risk of them infecting others (Brooks et al., 2019). In short, quarantine can generate a strong reduction of the transmission of viral infectivity. In the presence of COVID-19 outbreak in North Italy, Italian government has applied the quarantine and lockdown from 11 March 2020 to 3 May 2020 for all Italy, adding also some holidays thereafter. In fact, Italy was not able to prevent the diffusion of of Coronavirus infection and has applied quarantine as a recovery strategy to lessen the health and socioeconomic damages caused by this pandemic. In addition, Italy applied non-pharmaceutical interventions based on physical distancing, school and store closures, workplace distancing, to avoid crowded places, similarly to measures applied to COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan (cf., Prem et al., 2020). The benefits to support these measures until May 2020 are aimed at delaying and reducing the height of epidemic peak, affording health-care systems more time to expand and respond to this emergency and, as a result reducing the final impact of COVID-19 epidemic in society. In general, non-pharmaceutical interventions are important factors to reduce the epidemic peak and the acute pressure on the health-care system (Prem et al., 2020; Fong et al., 2020). However, Brooks et al. (2019) report: “negative psychological effects of quarantine including post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion, and anger. Stressors included longer quarantine duration, infection fears, frustration, boredom, inadequate supplies, inadequate information, financial loss, and stigma. Some researchers have suggested long-lasting effects. In situations where quarantine is deemed necessary, officials should quarantine individuals for no longer than required, provide clear rationale for quarantine and information about protocols, and ensure sufficient supplies are provided. Appeals to altruism by reminding the public about the benefits of quarantine to wider society can be favourable”.

This strategy, of course, does not prevent future epidemics similar to the COVID-19 and it does not protect regions from future Coronavirus disease threats on population. Nations have to apply proactive strategies that anticipate these potential problems and prevent them, for reducing the health and economic impact of future epidemics in society.

5.1. Suggested proactive strategies to prevent future epidemics similar to COVID-19

Daszak et al. (2020) argue that to prevent the next epidemics similar to COVID-19, research and investment of nations should focus on:

-

1)

surveillance among wildlife to identify the high-risk pathogens they carry

-

2)

surveillance among people who have contact with wildlife to identify early spillover events

-

3)

improvement of market biosecurity regarding the wildlife trade.

In addition, the application of best practices of high surveillance and proper biosafety procedures in public and private institutes of virology that study viruses and new viruses to avoid that may be accidentally spread in surrounding environments with damages for population, vegetation and overall economy of nations. In this context, international collaboration among scientists is basic to address these risks and support decisions of policymakers to prevent future pandemic that creates huge socioeconomic issues worldwide (cf., Coccia and Wang, 2016).4 In fact, following the COVID-19 outbreak, The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) points out that the global economy may contract of about by 2.5% and Italy by −7% of real GDP growth% in 2020 (EIU, 2020). Italy and other advanced countries should introduce organizational, product and process innovations to cope with future epidemics and environmental threats, such as the expansion of hospital capacity and testing capabilities, reduction of diagnostic and health system delays (also using devices with artificial intelligence, new Information and Communication Technologies for alleviating and/or eliminating effective interactions between infectious and susceptible individuals), and finally of course the development of effective vaccines and antivirals that can counteract future global public health threats in the presence of new epidemics similar to COVID-19 (Chen et al., 2020; Wilder-Smith et al., 2020; Riou and Althaus, 2020; Yao et al., 2020; cf., Coccia, 2015, Coccia, 2017a, Coccia, 2017b, Coccia, 2017c, Coccia, 2020; Coccia, 2020). New technology, for years to come, can cope with consequential epidemic outbreaks, also redefining the way governments interact with their citizens, such as the expanded use of surveillance tools, defending against cyberattacks and misinformation campaigns, etc. (cf., Coccia, 2016a, Coccia, 2016b, Coccia, 2019). This study here shows that accelerated diffusion of COVID-19 is also likely associated with high air pollution and specific meteorological conditions (low wind speed, etc.) of North Italy and other Northern Italian regions that favor the transmission dynamics of viral infectivity. North Italy is one of the European regions with the highest motorization rate and polluting industrialization (cf., Legambiente, 2019). In 2018, the daily limits for PM10 or ozone were exceeded in 55 provincial capitals (i.e., 35 days for PM10 and 25 days for ozone). In 24 of the 55 Italian province capitals, the limit was exceeded for both parameters, with negative effects on population and subsequent health problems in the short and long run. In fact, Italian cities having a very high number of polluted days are mainly in North Italy: e.g., Brescia with 150 days (47 days for the PM10 and 103 days for the ozone), Lodi with 149 days (78 days for the PM10 and 71 days for the ozone), -these are two cities with severe COVID-19 outbreak-, Monza (140 days), Venice (139 days), Alessandria (136 days), Milan (135 days), Turin (134 days), Padua (130 days), Bergamo and Cremona (127 days), Rovigo (121 days) and Genoa (103 days). These provincial capitals of the River Po area in Italy have exceeded in 2018 at least one of the two limits just mentioned. The first city not located in the Po Valley is Frosinone (Lazio region in the central part of Italy) with 116 days of exceedance (83 days for the PM10 and 33 days for the ozone), followed by Avellino, a city close to Naples in South Italy (with total 89 days: 46 days for PM10 and 43 days for ozone) and Terni with 86 days (respectively 49 and 37 days for the two pollutants). Many cities in Italy are affected by air pollution and smog because of traffic, domestic heating, industries and agricultural practices and private cars that continue to be by far the most used means of transportation (more than 39 million cars in 2019).

A major source of emissions of nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere is the combustion of fossil fuels from stationary sources (heating, power generation, etc.) and motor vehicles. In Italy, the first COVID-19 outbreak has been found in Codogno, a small city close to Milan (Lombardy region in North Italy, see Fig. 3). Although local lockdown on February 25, 2020, the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection showed concentrations of PM10 beyond the limits in almost all of Lombardy region. The day after, February 26, 2020, the high intensity of wind speed swept the entire Po Valley, bringing to Lombardy region a substantial reduction in the average daily concentrations of PM10 (i.e., lower than 50 micrograms of particulate matter/m3 of air). These observations associated with statistical analyses here suggest that high concentration of nitrogen dioxide of particulate air pollutants emitted by motor vehicles, power plants, and industrial facilities in North Italy seems to be a platform to support the diffusion of viral infectivity (cf., Groulx et al., 2018), increase hospitalizations for respiratory disorders (cf., Carugno et al., 2018; Nenna et al., 2017), increase asthma incidence (cf., Liao et al., 2011) and induce damages to the immune system of people (cf., Glencross et al., 2020). As a matter of fact, transmission dynamics of COVID-19 has found in air pollution and meteorological conditions of North Italy an appropriate environment and population for an accelerated diffusion that is generating more than 26,640 deaths and a huge number of hospitalizations in a short period of time (February–March–April 2020).