Abstract

Objective

Most women suffering from tubal factor infertility do not have a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, but rather have asymptomatic upper genital tract infection. Investigating the impacts of such infections, even in the absence of clinically confirmed pelvic inflammatory disease, is critical to understanding the tubal factor of infertility. The aim of this study was to investigate whether the presence of endocervical bacteria is associated with tubal factors in women screened for infertility.

Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study involved 245 women undergoing hysterosalpingography (HSG), screened for endocervical colonization by Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis, as part of a routine female infertility investigation between 2016 and 2017.

Results

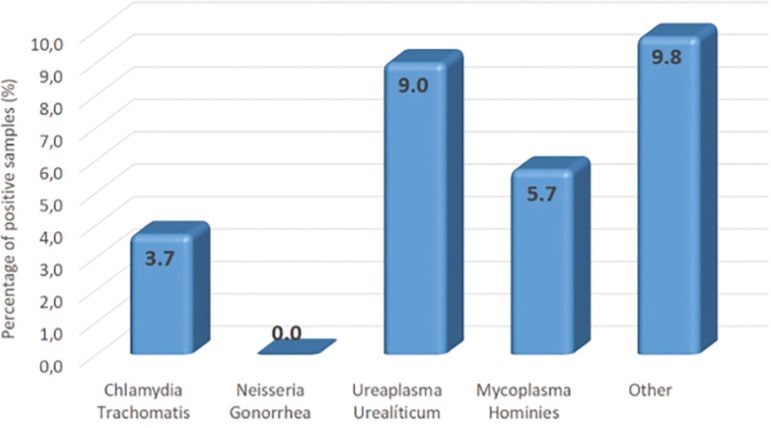

endocervical bacterial colonization by Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealiticum, Mycoplasma hominis and other bacteria corresponded to 3.7%, 9.0%; 5.7% and 9.8%, respectively. There was no colonization by Neisseria gonorrhea. The prevalence of tubal factor was significantly higher in patients with positive endocervical bacteria colonization, regardless of bacterial species. When evaluating bacteria species individually, the women who were positive for endocervical Mycoplasma hominis had significantly higher rates of tubal factor. Associations between endocervical bacterial colonization and tubal factor infertility were confirmed by multiple regression analysis adjusted for age and duration of infertility.

Conclusion

Besides the higher prevalence of Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma infectious agents, the findings of this study suggest the possible association of endocervical bacterial colonization - not only Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea, but also Mycoplasma species with tubal performance.

Keywords: endocervical bacteria, tubal factor, hysterosalpingography, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections are a major health issue and are implicated in a number of conditions, including female infertility. Despite the overall importance of genital tract infection still being discussed, tube-peritoneal damage seems to be the foremost way in which infections affect women’s fertility. Pathogenic microorganisms colonizing the lower female genital tract may ascend to the upper genital tract, causing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) associated with tubal damage, and ultimately to infertility. In the presence of infection, tubal damage may occur in response to adhesions, damage to the tubal mucosa or tubal occlusion impairing oocyte transport (Rhoton-Vlasak, 2000).

Infertility is estimated to affect one in every seven couples in the western world, and one in every four couples in developing countries, with rates of up to 30% in some regions of Africa (Vander Borght & Wyns, 2018). Despite differing estimates concerning the global infertility prevalence, secondary infertility is the most common form of female infertility worldwide, and it is often due to reproductive tract infections with resulting tubal factors (Inhorn & Patrizio, 2015). The risk of infertility is directly proportional to the number of PID episodes, with tubal damage occurring in approximately 15% of the cases. However, most women suffering from tubal factor infertility do not have a history of PID, but rather of asymptomatic upper genital tract infection. Therefore, investigating the impacts of such infections, particularly in the absence of clinically confirmed PID, is critical to understanding the relationship between genital tract infections and tubal factor infertility (Tsevat et al., 2017).

A meta-analysis showed that bacterial vaginosis is significantly more prevalent in infertile women and women with tubal factors (van Oostrum et al., 2013). Higher prevalence of asymptomatic vaginosis in infertile compared to healthy women has also been recently reported (Babu et al., 2017), and the vaginal microbiome is thought to be associated with in vitro fertilization (IVF) outcomes; and therefore, with pregnancy outcomes (Hyman et al., 2012).

Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis) infection, a significant global public health issue, is strongly associated with tubal factor infertility and a cause of PID-related morbidity (i.e., infertility and ectopic pregnancy) (Sirota et al., 2014). Neisseria gonorrhoeae( N. gonorrhoeae) is also known to cause PID, but both infections (C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae) may be asymptomatic in some women, and many patients go undiagnosed and untreated (Kreisel et al., 2017). Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma hominis (M. hominis) and Ureaplasma urealyticum (U. urealyticum) are thought to be opportunistic pathogens in humans, and are often found in the genitourinary tract of healthy women. However, both species have been associated with increased risks of certain pathological conditions, including bacterial vaginosis (Keane et al., 2000) and PID (Taylor-Robinson et al., 2012).

Except for C. trachomatis, there are no reports in the literature confirming the association of asymptomatic endocervical bacteria colonization and tubal factor infertility. This study set out to investigate the association between asymptomatic endocervical bacterial colonization by C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, M. hominis and U. urealyticum, and tubal factor infertility in women submitted to initial fertility investigation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

Retrospective cross-sectional study including women undergoing initial infertility investigation at the Instituto Gera de Medicina Reprodutiva, a private reproductive medicine center in São Paulo, Brazil. Procedures in this study are part of routine care at that center. All participants signed an informed consent form and allowed their retrospective data to be used for scientific publication purposes, provided anonymity was respected. Therefore, the study was exempt from approval by the Institutional Review Board.

The medical records of patients seen at the Instituto Gera de Medicina Reprodutiva between 2016 and 2017 (n=369) were reviewed, and those reporting both hysterosalpingography (HSG) and endocervical screening for bacterial colonization (n=245) were included in the study. The remaining 124 women were not submitted to HSG due to other classical indications for IVF treatment, such as severe male factor infertility, recurrent miscarriage, a history of salpingectomy or very low ovarian reserve, and were therefore excluded from the analysis.

Procedures

Selected patients were undergoing their first complete infertility investigation. We collected clinical history, serum hormone, transvaginal ultrasound, hysteroscopy, HSG and endocervical screening data. Endocervical screening for C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhea, U. urealiticum and M. hominis was requested at the first visit and performed using standard PCR procedures at an outsourced clinical analysis laboratory. Other colonizing bacteria were identified by routine culture of endocervical discharge. All patients were asymptomatic for genital tract infection and results of PCR and the bacterial culture was classified as positive or negative. Patients positive for C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhea, U. urealiticum or M. hominis were treated with doxycycline (100/mg every 12 hours for 14 days). Infections by other bacteria identified in positive cultures were treated according to results from the antimicrobial susceptibility test.

The 245 women included in the sample were submitted to HSG by a reproductive medicine specialist and classified as having normal or abnormal fallopian tubes. Abnormal tubal findings determined a tubal factor infertility and included any peritubal and/or periovarian adhesions, proximal or distal occlusion or extensive periadnexal adhesions in at least one tube.

Statistical analysis

We investigated the association between endocervical bacteria colonization and tubal factor infertility. Proportions were presented for categorical data and compared using the Chi-square or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SD) and compared using the Student’s t-test. We made a regression analysis to investigate associations between the presence of endocervical bacteria and tubal factor adjusted for confounders. Statistical analyzes were performed using the SPSS software package (IBM Software Group, USA). We set the level of significance at 5% (p≤0.05).

RESULTS

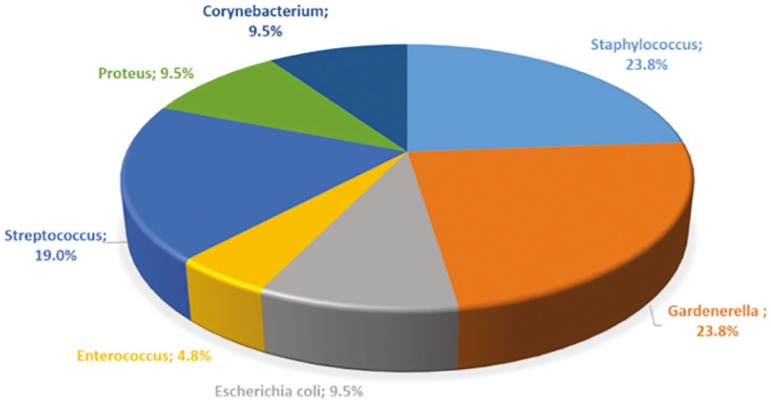

The women in this sample had between 22 and 48 years of age (36.3±4.6). Other demographic characteristics were as follows: mean duration of infertility, 4.2 years; mean baseline FSH, 10.2±16.6IU/ml and mean anti-Müllerian hormone levels, 2.6±2.9ng/ml. The overall prevalence of endocervical bacterial colonization was 18.2% and tubal factor infertility was detected in 55.5%. Figure 1 depicts the types of bacteria and respective prevalence rates. Gardnerella and Staphylococcus (Figure 2) were the most prevalent bacterial genera among other micro-organisms identified in conventional culture of endocervical discharge.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of endocervical bacteria in the population studied

Figure 2.

Representative graph of type of bacteria found in the conventional bacterial culture of endocervical samples

We split the patients into two groups according to the results of bacterial endocervical testing as negative (n=199) or positive (n=46). The demographic characteristics between groups were similar and described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of women presenting negative or positive endocervical bacterial colonization

| Endocervical bacteria colonization | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | p | |

| N | 199 | 46 | |

| Age (years) | 35.8±4.4 | 35.8±5.6 | 0.955 |

| Duration of infertility (years) | 4.2±2.9 | 4.1±3.9 | 0.974 |

| Baseline FSH (IU/ml) | 8.2±5.1 | 6.8±3.2 | 0.160 |

| Anti-Mullerian hormone (ng/ml) | 2.7±3.0 | 2.5±2.1 | 0.822 |

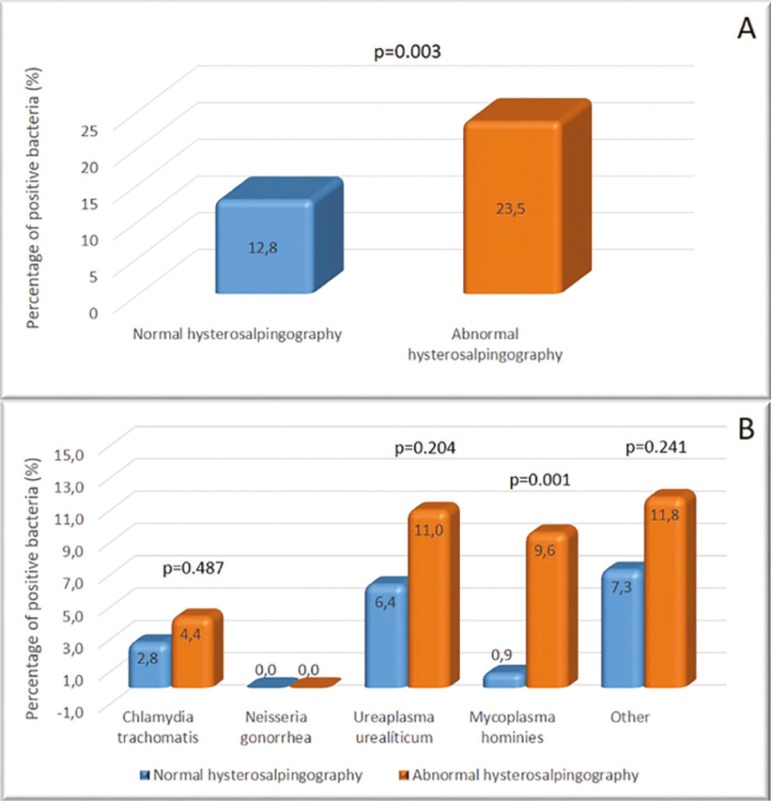

Tubal factor infertility was more prevalent in women with endocervical bacteria colonization, regardless of bacterial species, suggesting an association between endocervical bacteria and tubal factors (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A - Representative graph of the prevalence of endocervical bacteria according to hysterosalpingography findings. B - Representative graph of the prevalence of different endocervical bacteria according to hysterosalpingography findings.

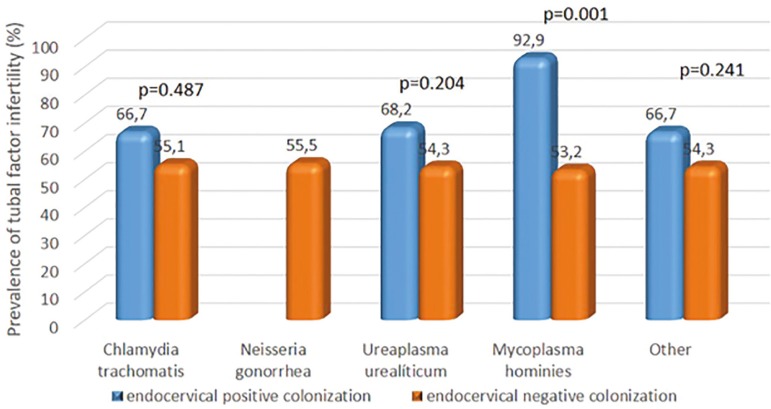

Separate analysis per bacteria also revealed higher percentages of tubal factor infertility when the endocervical colonization was present for each bacteria. However, significant results were limited to Mycoplasma hominis (Figure 4). Interestingly, among patients positive for Mycoplasma hominis, only one had normal fallopian tubes.

Figure 4.

Endocervical colonization. Separate analysis per bacteria also revealed higher percentages of tubal factor infertility when the endocervical positive colonization was present for each bacteria. However, significant results were limited to Mycoplasma hominis.

Multiple logistic regression models adjusted for age and duration of infertility were used to confirm associations between endocervical bacterial colonization and tubal factor infertility in this study. Endocervical bacterial colonization was associated with a 2.2-fold increase in the odds of tubal factor infertility (OR: 2.2; p=0.028), thereby confirming our findings.

DISCUSSION

We screened the women in this study for endocervical bacterial colonization as part of an infertility investigation, and 18.2% of the patients tested positive for endocervical bacteria, despite of all being asymptomatic. We found a significant association between tubal factor infertility and endocervical bacterial colonization. However, only Mycoplasma hominis was significantly associated with tubal factors following separate analysis per bacteria, despite numerically higher rates of tubal factors in the presence of Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum and other bacteria diagnosed by culture of endocervical discharge.

Infection by some of these agents, such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea, is known to negatively affect the female reproductive tract. Previous investigations of the Brazilian population revealed comparatively higher prevalence rates of these agents (6.3% and 4.0%; C. trachomatis, and N. gonorrhoeae, respectively) (Rodrigues et al., 2011) than we found in our sample. Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis were the most prevalent bacteria in this sample. This finding is in sync with those from Rodrigues et al. (2011) (38.4% and 21.9% prevalence, Ureaplasma sp and M. hominis, respectively), despite higher percentages reported in that study. In another Brazilian study, the prevalence of C. trachomatis was 10.9% and only two cases of N. gonorrhea infection were detected in a population of infertile women (Fernandes et al., 2014).

Anyway, studies demonstrate that the prevalence of endocervical bacterial infection varies between populations. A Mexican study showed 21.7% and 6.5% of U. urealyticum and M. hominis prevalence in infertile women, and associated the outcomes with tubal damage in a very small group of patients (Hernández-Marín et al., 2016). A Czech study reported 39.6% and 8.1% prevalence of U. urealyticum and M. hominis in positive endocervical swabs of women undergoing initial fertility testing, respectively (Sleha et al., 2016). In contrast, a North American study conducted in New York revealed a 17.2% and 2.1% prevalence of U. urealyticum and M. hominis in the endocervix at the time of oocyte collection in women undergoing IVF, respectively (Witkin et al., 1995). Prevalence rates of 9.0% and 8.6% (U. urealyticum and M. hominis, respectively) were reported in women of reproductive age in an Italian study (Leli et al., 2018) and, as in this study, U. urealyticum was the most common bacteria found in the cervical samples of infertile women in Germany (Graspeuntner et al., 2018). These differences in prevalence’s may have reflected disparities in geographical location, medical care (i.e., public or private), population studied and methods for diagnosis used.

A World Health Organization taskforce has been working towards the prevention of tubal infertility for more than two decades, with particular emphasis on the diagnosis of lower genital tract infections. Women infected with N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are significantly more prone to bilateral tubal occlusion, despite the lack of pelvic inflammatory disease symptoms (WHO, 1995). Regarding other bacteria, a study screening couples for Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum, found 48% of infertile men and 40% of infertile women positive for Ureaplasma urealyticum, with high levels of agreement between positive test results in men and women. Also, lower sperm motility and vitality in Ureaplasma urealyticum-positive men suggests negative impacts on male fertility (Lee et al., 2013). Similar relationships between Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum colonization and male infertility have been reported elsewhere (Huang et al., 2015).

Except for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis, the cause-effect relationship of those bacteria colonization and tubal factor infertility are not confirmed. However, endocervical bacterial colonization may lead to vaginal environment imbalances and may be a cofactor in other, more significant infections. The induction of proinflammatory cytokines by abnormal vaginal flora has been associated with bacterial vaginosis. Also, abnormal vaginal flora may furtively invade the uterine cavity, leading to significant endometrial inflammation and immunological changes which, if left untreated, may have serious consequences, including unexplained infertility, tubal obstruction, miscarriage and preterm birth (Viniker, 1999; Spandorfer et al., 2001). Bacterial growth has been documented in patients with uterine pathologies such as endometritis, despite the absence of signs of infection (Cicinelli et al., 2008). Moreover, IVF outcomes are thought to be affected by the vaginal microbiome on the day of embryo transfer (Hyman et al., 2012), and endometrial development towards a proper receptive status, including the establishment of a suitable local immune environment, is influenced by uterine microbiota (Benner et al., 2018).

A recent study investigating different sites of the female reproductive tract revealed that distinct bacterial communities form a microbiota continuum from the vagina to the ovaries. The same study also revealed correlations between bacteria detected in the peritoneal fluid and the cervical microbiota, suggesting cervical mucosa sampling may be used to assess endometrial status (Chen et al., 2017). Those findings support the association of microbiota in the upper and lower reproductive tracts and then inferred microbial cervical function in uterine-related diseases, in line with association of cervical infection and tubal factor of infertility which was the subject of our study.

Most cases of tubal infertility are actually due to salpingitis, which often results from previous or persistent infections. Bacteria may ascend from the cervical mucosa to the endometrium and fallopian tubes, leading to clinical PID, which in turn is strongly associated with tubal infertility (Ross et al., 2018). However, a number of women presenting tubal infertility tend to develop asymptomatic genital tract infections, and therefore do not have a history of PID (Wiesenfeld et al., 2012). Then, bacterial vaginosis is thought to be a key factor in upper genital tract disease; still, the link between infection and its respective sequelae, such as infertility, remains to be determined (Graspeuntner et al., 2018).

A previous metanalysis showed that bacterial vaginosis is more prevalent in infertile women (van Oostrum et al., 2013). Findings from our study suggest endocervical bacterial colonization, particularly by Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum, is associated with tubal factor infertility in asymptomatic infertile women. The regression model employed supported this association, given the two-fold higher odds of tubal factors in women presenting with endocervical bacterial colonization, regardless of bacteria type. However, our study has limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study and then we may state that there is a possible association between bacterial colonization and tubal factor infertility, but the cause-effect relationship may not be confirmed. Moreover, infertile women with indications for HSG were included in the sample of our study and those with other infertility factors as male infertility, endometriosis, ovarian failure, etc., did not undergo HSG and were not included. In face of that, the prevalence of tubal changes (55%) was higher compared to literature data (up to 30% of tuboperitoneal infertility) (Evers, 2002).

In spite of the evidence of association between Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma infection with infertility (Sleha et al., 2016; Witkin et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2013; van Oostrum et al., 2013; Graspeuntner et al., 2018) and spontaneous preterm birth resulting from induced inflammation (Murtha & Edwards, 2014), the European STI Guidelines Editorial Board does not recommend routine testing or treatment for asymptomatic or symptomatic male and female patients with M. hominis, U. urealyticum or U. parvum (Horner et al., 2018). A consensus as to whether or not such infections should always be treated is lacking and there are controversies regarding the classification of Mycoplasma species as pathogenic and worthy of treatment or part of the non-pathogenic bacterial flora (Patel & Nyirjesy, 2010).

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis evaluated by PCR, in endocervical samples of infertile women and their potential association with HSG findings. The current diagnostic workflow for female infertility comprises clinical history analysis and serological screening for previous sexually transmitted infections (STI), as well as the investigation of reproductive tract abnormalities. Findings of this study suggest the possible association of endocervical bacterial colonization - not only for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea, but also for Mycoplasma species such as Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis - with tubal functioning. The latter organisms are not the focus of investigation in the routine infertility clinics, but ours and other studies demonstrated their high prevalence and having been associated with higher odds of tubal factor of infertility in this sample. Other studies should be developed to confirm the cause-effect relationship between Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis endocervical infection and tubal factor infertility.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge all members of the GERA Instituto de Medicina Reprodutiva team for their invaluable support with patients and procedures. They also thank Tatiana CS Bonetti, PhD, for her assistance on data analysis and manuscript writing.

Footnotes

This study was presented as a poster at the ESHRE Annual Meeting 2018, held in Barcelona - Spain on July 01-04, 2018.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Babu G, Singaravelu BG, Srikumar R, Reddy SV, Kokan A. Comparative Study on the Vaginal Flora and Incidence of Asymptomatic Vaginosis among Healthy Women and in Women with Infertility Problems of Reproductive Age. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:DC18–DC22. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/28296.10417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner M, Ferwerda G, Joosten I, van der Molen RG. How uterine microbiota might be responsible for a receptive, fertile endometrium. Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24:393–415. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmy012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Song X, Wei W, Zhong H, Dai J, Lan Z, Li F, Yu X, Feng Q, Wang Z, Xie H, Chen X, Zeng C, Wen B, Zeng L, Du H, Tang H, Xu C, Xia Y, Xia H, Yang H, Wang J, Wang J, Madsen L, Brix S, Kristiansen K, Xu X, Li J, Wu R, Jia H. The microbiota continuum along the female reproductive tract and its relation to uterine-related diseases. Nat Commun. 2017;8(875) doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00901-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicinelli E, De Ziegler D, Nicoletti R, Colafiglio G, Saliani N, Resta L, Rizzi D, De Vito D. Chronic endometritis: correlation among hysteroscopic, histologic, and bacteriologic findings in a prospective trial with 2190 consecutive office hysteroscopies. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:677–684. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers JL. Female subfertility. Lancet. 2002;360:151–159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes LB, Arruda JT, Approbato MS, Garcia-Zapata MT. Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection: factors associated with infertility in women treated at a human reproduction public service. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2014;368:353–358. doi: 10.1590/SO100-720320140005009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graspeuntner S, Bohlmann MK, Gillmann K, Speer R, Kuenzel S, Mark H, Hoellen F, Lettau R, Griesinger G, Konig IR, Baines JF, Rupp J. Microbiota-based analysis reveals specific bacterial traits and a novel strategy for the diagnosis of infectious infertility. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Marín I, Aragón-López CI, Aldama-González PL, Jiménez-Huerta J. Prevalence of infections (Chlamydia, Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma) in patients with altered tuboperitoneal factor. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2016;84:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner P, Donders G, Cusini M, Gomberg M, Jensen JS, Unemo M. Should we be testing for urogenital Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum in men and women? - a position statement from the European STI Guidelines Editorial Board. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1845–1851. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Zhu HL, Xu KR, Wang SY, Fan LQ, Zhu WB. Mycoplasma and ureaplasma infection and male infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrology. 2015;35:809–816. doi: 10.1111/andr.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman RW, Herndon CN, Jiang H, Palm C, Fukushima M, Bernstein D, Vo KC, Zelenko Z, Davis RW, Giudice LC. The dynamics of the vaginal microbiome during infertility therapy with in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29:105–115. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9694-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn MC, Patrizio P. Infertility around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:411–426. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane FE, Thomas BJ, Gilroy CB, Renton A, Taylor-Robinson D. The association of Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma genitalium with bacterial vaginosis: observations on heterosexual women and their male partners. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11:356–360. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisel K, Torrone E, Bernstein K, Hong J, Gorwitz R. Prevalence of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Sexually Experienced Women of Reproductive Age - United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:80–83. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6603a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Kim KT, Lee HS, Yang KM, Seo JT, Choe JH. Concordance of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in infertile couples: impact on semen parameters. Urology. 2013;81:1219–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leli C, Mencacci A, Latino MA, Clerici P, Rassu M, Perito S, Castronari R, Pistoni E, Luciano E, De Maria D, Morazzoni C, Pascarella M, Bozza S, Sensini A. Prevalence of cervical colonization by Ureaplasma parvum, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis and Mycoplasma genitalium in childbearing age women by a commercially available multiplex real-time PCR: An Italian observational multicentre study. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2018;51:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtha AP, Edwards JM. The role of Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma in adverse pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:615–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MA, Nyirjesy P. Role of Mycoplasma and ureaplasma species in female lower genital tract infections. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoton-Vlasak A. Infections and infertility. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 2000;7:200–206. doi: 10.1016/S1068-607X(00)00047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues MM, Fernandes PÁ, Haddad JP, Paiva MC, Souza Mdo C, Andrade TC, Fernandes AP. Frequency of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Mycoplasma genitalium, Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma species in cervical samples. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:237–241. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2010.548880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J, Guaschino S, Cusini M, Jensen J. 2017 European guideline for the management of pelvic inflammatory disease. Int J STD AIDS. 2018;29:108–114. doi: 10.1177/0956462417744099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirota I, Zarek SM, Segars JH. Potential influence of the microbiome on infertility and assisted reproductive technology. Semin Reprod Med. 2014;32:35–42. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1361821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleha R, Boštíková V, Hampl R, Salavec M, Halada P, Štěpán M, Novotná Š, Kukla R, Slehová E, Kacerovský M, Boštík p. Prevalence of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in women undergoing an initial infertility evaluation. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2016;65:232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spandorfer SD, Neuer A, Giraldo PC, Rosenwaks Z, Witkin SS. Relationship of abnormal vaginal flora, proinflammatory cytokines and idiopathic infertility in women undergoing IVF. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:806–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS, Svenstrup H, Stacey CM. Difficulties experienced in defining the microbial cause of pelvic inflammatory disease. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23:18–24. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsevat DG, Wiesenfeld HC, Parks C, Peipert JF. Sexually transmitted diseases and infertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oostrum N, De Sutter P, Meys J, Verstraelen H. Risks associated with bacterial vaginosis in infertility patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:1809–1815. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Borght M, Wyns C. Fertility and infertility: Definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem. 2018;62:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viniker DA. Hypothesis on the role of sub-clinical bacteria of the endometrium (bacteria endometrialis) in gynaecological and obstetric enigmas. Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5:373–385. doi: 10.1093/humupd/5.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Meyn LA, Amortegui AJ, Sweet RL. Subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:37–43. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825a6bc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkin SS, Kligman I, Grifo JA, Rosenwaks Z. Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis detected by the polymerase chain reaction in the cervices of women undergoing in vitro fertilization: prevalence and consequences. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1995;12:610–614. doi: 10.1007/BF02212584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization - WHO Tubal infertility: serologic relationship to past chlamydial and gonococcal infection. World Health Organization Task Force on the Prevention and Management of Infertility. Sex Transm Dis. 1995;22:71–77. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]