Abstract

For the clinical management of sepsis, antibody-based strategies have only been attempted to antagonize pro-inflammatory cytokines, but not yet been tried to target harmless proteins that may interact with these pathogenic mediators. Here we report an antibody strategy to intervene in the harmful interaction between tetranectin (TN) and a late-acting sepsis mediator, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), in pre-clinical settings. We discovered that TN could bind HMGB1 to reciprocally enhance their endocytosis, thereby inducing macrophage pyroptosis and consequent release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain (ASC). The genetic depletion of TN expression or supplementation of exogenous TN protein at sub-physiological doses distinctly affected the outcomes of potentially lethal sepsis, revealing a previously under-appreciated beneficial role of TN in sepsis. Furthermore, the administration of domain-specific polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies effectively inhibited TN/HMGB1 interaction and endocytosis and attenuated the sepsis-induced TN depletion and tissue injury, thereby rescuing animals from lethal sepsis. Our findings point to a possibility of developing antibody strategies to prevent harmful interactions between harmless proteins and pathogenic mediators of human diseases.

One Sentence Summary:

An antibody strategy prevents harmful TN/HMGB1 interaction and resultant macrophage pyroptosis and immunosuppression in sepsis.

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection that annually claims hundreds of thousands of victims in the U.S. alone (1, 2). Its complex pathogenesis is partly attributable to both dysregulated inflammatory responses and resultant immunosuppression (2, 3). The high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) protein is released by activated macrophages/monocytes and functions as a late mediator of lethal endotoxemia (4) and sepsis (5, 6). When initially secreted by innate immune cells in relatively low amounts, HMGB1 might still be proinflammatory during an early stage of sepsis (4). However, when it is passively released by the liver (7) and other somatic cells in overwhelmingly higher quantities, HMGB1 could also induce immune tolerance (8, 9), macrophage pyroptosis (7, 10), and immunosuppression (11), thereby impairing the host’s ability to eradicate microbial infections (12, 13). It was previously unknown what other endogenous proteins could affect extracellular HMGB1 functions and could be pharmacologically modulated for treating inflammatory diseases.

In 1986, tetranectin (TN) was first characterized as an oligomeric plasminogen-binding protein (14) with an overall 76% amino acid sequence identity (87% similarity) between human and rodents (15). It is expressed most abundantly in the lung (16, 17), and its blood concentrations in healthy humans range from moderate (~ 8 μg/ml) in infants to high (10–12 μg/ml) in adults (18). Structurally, TN has several distinct domains responsible for its extracellular secretion (residue 1–21, leader signal sequence), heparin binding (residue 22–37) (19), oligomerization (residue 47–72, the α-helical domain), as well as carbohydrate recognition (residue 73–202) of oligosaccharides in plasminogen (20, 21), apolipoprotein A1 (22), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) (23). However, the specific roles of TN in physiology and pathology remain poorly understood. Recent evidence revealed that enhanced expression or genetic depletion of TN caused abnormal osteogenesis (24), excessive curvature of the thoracic spine (25), deficient motor function (such as limb rigidity) (26), or impaired wound healing (27, 28), implying the importance of maintaining physiological TN concentrations in health.

Previously, it was unknown whether blood TN concentrations were altered during clinical and experimental sepsis, and whether these could be pharmacologically modulated to fight against inflammatory diseases. In the present study, we sought to understand the role of TN in lethal sepsis by examining its dynamic changes in sepsis and possible interaction with HMGB1, and determine how alterations of TN concentrations (genetic depletion or pharmacological supplementation) or activities (using domain-specific antibodies) affect the outcomes of lethal sepsis in pre-clinical settings.

RESULTS

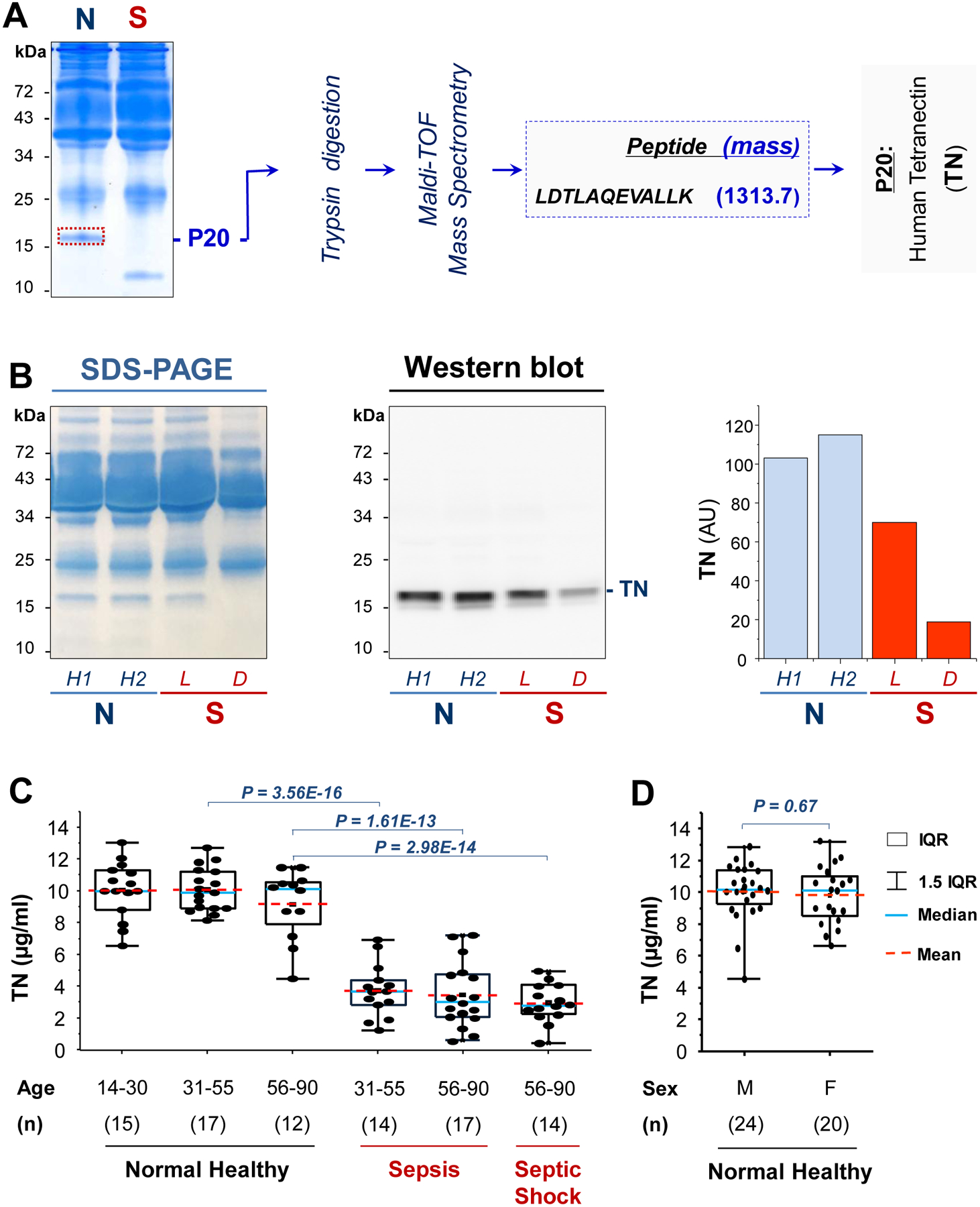

Blood TN was depleted in septic patients

To search for endogenous proteins modulating HMGB1 functions, we characterized the dynamic changes of serum HMGB1 and other proteins in a group of septic patients admitted to the Northwell Health System. In a septic patient with elevated serum HMGB1 (“S”, Fig. 1A), the concentration of a 20-kDa protein (denoted as “P20”) was much lower than that of a normal healthy subject (“N”, Fig. 1A). This protein was identified as human tetranectin (TN) by in-gel trypsin digestion and mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 1A). To further verify its identity, we immunoblotted serum samples from two normal healthy controls (“N”, Fig. 1B) and two septic patients (“S”) who either survived (“L”) or died (“D”) of sepsis with a TN-specific rabbit mAb (table S1). As expected, this mAb specifically recognized a 20-kDa band in the serum of healthy humans (Fig. 1B) and animals (fig. S1A), but not in the serum or lungs of TN-deficient mice (fig. S1A). Moreover, immunoblotting assays confirmed a marked reduction of serum TN concentration in a sepsis survivor (“L”, Fig. 1B), and an almost complete TN depletion in a patient who died of septic shock within 24 h of the initial diagnosis and blood sampling (“D”, Fig. 1B). Statistical analysis of a larger cohort of age-matched healthy controls and critically ill patients revealed a 62–67% reduction of plasma TN concentrations in patients with sepsis or septic shock (Fig. 1C), confirming a marked loss of plasma TN in sepsis. These observed differences between normal controls and septic patients were not likely skewed by occasionally imbalanced gender ratios (for example, 11/6 versus 6/11; table S2), because there was no significant difference in plasma TN concentrations between male and female healthy controls (P = 0.67, Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. Identification of tetranectin (TN) as a serum protein depleted in septic patients.

(A) Mass spectrometry analysis of a 20-kDa (P20) protein, which was abundant in a normal healthy subject (N), but depleted in a septic patient who died (S) of sepsis within 72 h of the initial diagnosis and blood sampling.

(B) SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analysis of serum TN in normal healthy controls (N) and septic patients who either survived (denoted as “L”) or died (“D”) of septic shock within 24 h of the initial diagnosis and blood sampling. Bar graph indicates the relative TN concentrations in arbitrary units (AU) in the serum samples.

(C) Box plot representation of plasma TN concentrations in normal healthy controls and patients with sepsis or septic shock. Data represent mean [interquartile range (IQR), 25 to 75%] value of plasma TN concentrations. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the means between different groups, and P values are indicated.

(D) Box plot representation of plasma TN concentrations in 24 male and 20 female healthy controls. The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA test was used to calculate the P value.

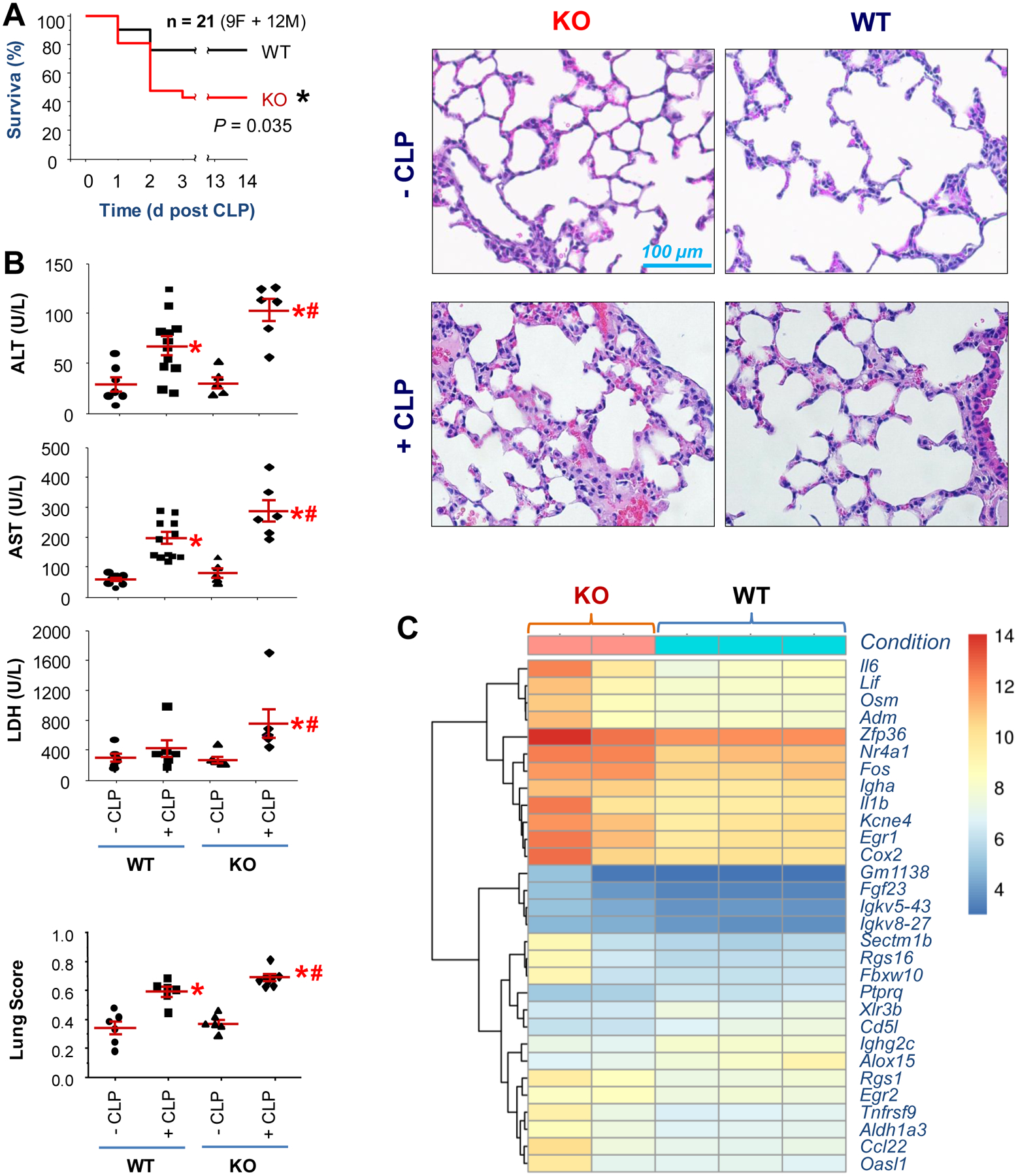

Genetic depletion of TN rendered mice more susceptible to lethal sepsis

To assess the role of TN in sepsis, we first determined how genetic TN depletion affects the sepsis-induced tissue injury and lethality in age-matched animals. The genotypes of wild-type and TN knock-out (KO) mice were confirmed by immunoblotting (fig. S1A) and genotyping (fig. S1B) analyses of serum, lung, and tail samples. TN KO mice exhibited a significantly higher mortality rate than that of age-matched wild-type littermate controls (P = 0.035; Fig. 2A), which was associated with an increased systemic release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), as well as liver alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (Fig. 2B). Histological analysis showed more severe inflammation and injury, as manifested by the increase in alveolar septal wall thickening, leukocyte infiltration, and alveolar congestion in the lungs of TN KO mice (Fig. 2B). Correspondingly, RNA-seq analysis revealed markedly increased gene expression of several proinflammatory mediators (for example, Il1b, Il6, Lif, Cox2) in the lungs of TN KO mice (Fig. 2C), indicating possible anti-inflammatory properties of lung TN in sepsis.

Fig. 2. Genetic depletion of TN rendered animals more susceptible to lethal sepsis.

(A) Age-matched wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J or TN KO mice were subjected to lethal sepsis, and animal survival was monitored for two weeks. n = 21 animals (9 females and 12 males) per group.

(B) In parallel experiments, blood and lung tissue were harvested at 24 h after CLP and assayed for tissue injury by measuring blood concentrations of tissue enzymes or lung histology. n = 6–12 animals per group. *, P < 0.05 versus sham control (-CLP); #, P < 0.05 versus WT CLP group (“+ CLP”).

(C) TN knockout exacerbated sepsis-induced gene expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the lung. A bi-clustering heat map was used to visualize the expression profile of the top 30 differentially expressed genes sorted by their adjusted P-value and log2 fold of changes. Each row represents a gene, and each column represents one sample from each animal.

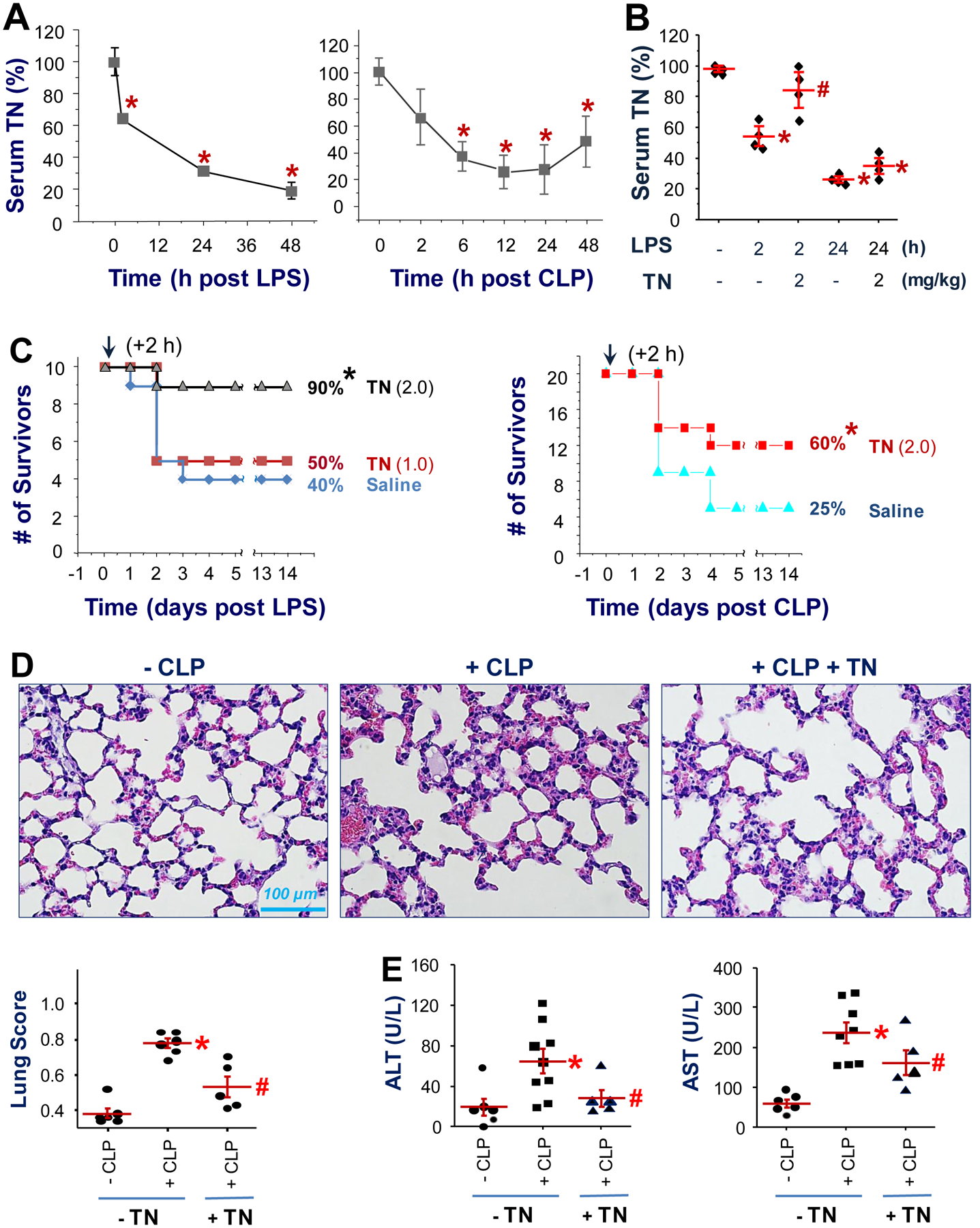

Supplementation of exogenous TN conferred dose-dependent protection against lethal endotoxemia and sepsis

In healthy animals, TN was most abundantly expressed in the lung, but also detected in the circulation (fig. S2A, S2B). Assuming a 25-g mouse with an average blood volume of 1.5 ml and a mean circulating TN concentration of 10.0 μg/ml (fig. S2B), the physiological blood TN concentration is estimated to be around 0.6 mg/kg body weight. After experimental endotoxemia and sepsis (Fig. 3A), circulating TN concentrations were decreased in a time-dependent fashion, with a > 70% reduction at 24 h after the onset of these diseases – a time point when some endotoxemic or septic animals started to succumb to death. Furthermore, the parallel reduction of TN content in the serum (fig. S3A) and lung tissue (fig. S3B) of endotoxemic animals supports the lung as a possible source of circulating TN (17).

Fig. 3. Supplementation of exogenous TN conferred protection against lethal endotoxemia and sepsis.

(A) Time-dependent reduction of circulating TN concentrations in murine models of lethal endotoxemia (LPS) and sepsis (CLP). Balb/C mice were subjected to lethal endotoxemia (LPS, i.p., 7.5 mg/kg) or CLP sepsis, and blood samples were harvested at various time points after LPS or CLP to measure TN concentrations by Western blotting analysis. n = 3 animals per group. *, P < 0.05 versus “time 0”.

(B) Balb/C mice were given LPS (i.p., 7.5 mg/kg) with or without human TN (i.p., 2.0 mg/kg), and animals were sacrificed 2 or 24 h later to harvest blood to measure serum TN concentrations. *, P < 0.05 versus time 0 (“-LPS-TN”); #, P < 0.05 versus “+ LPS-TN” at the same time point, n = 4 animals per group.

(C) Recombinant human TN was given at indicated doses (1.0 or 2.0 mg/kg, i.p.) at 2 h after the onset of lethal endotoxemia or sepsis. Animal survival was monitored for two weeks to ensure long-lasting protection. *, P < 0.05 versus saline control group. n = 10 animals per group for the LPS model; n = 20 animals per group for the CLP model.

(D) Recombinant murine TN (0.1 mg/kg) was given at 2 and 24 h after CLP, and animals were sacrificed at 28 h after CLP to harvest lung tissue for histological analysis. *, P < 0.05 versus “-CLP” group; #, P < 0.05 versus “+ CLP” group. n = 5 – 6 animals per group.

(E) At 28 h after CLP, animals were euthanized to harvest blood to measure serum concentrations of ALT and AST. *, P < 0.05 versus sham control (“-CLP”); #, P < 0.05 versus saline group (“+ CLP”). n = 5 – 9 animals per group.

We then determined how purified human or murine TN proteins expressed in HEK293 kidney cells or E. coli (fig. S4) affect the outcomes of lethal endotoxemia and sepsis. Recombinant murine TN migrated on SDS-PAGE gel as a 17 and 24 kDa band in the absence of a reducing agent (dithiothreitol, DTT, fig. S4B), but migrated as 24 kDa band in the presence of DTT (fig. S4B), suggesting a possible variation of the redox status of different cysteines of TN protein (fig. S4A). The supplementation of endotoxemic mice with recombinant human TN (2.0 mg/kg) partially restored blood TN concentrations at 2 h after LPS, which were then gradually diminished by 24 h (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the intraperitoneal administration of either eukaryote-derived human TN (Fig. 3C) or prokaryote-derived murine TN (fig. S5) conferred a reproducible and dose-dependent protection against lethal endotoxemia (Fig. 3C, left) and sepsis (Fig. 3C, right; fig. S5A), supporting a beneficial role of TN in lethal systemic inflammation. Correspondingly, supplementation of exogenous TN led to a marked attenuation of sepsis-induced injury in the lung (Fig. 3D) and liver (Fig. 3E), further confirming a protective role of TN in lethal sepsis. Because there was only 79% (159/202) amino acid sequence identity [and 87% (174/202) similarity] between human and mouse, a lower dose of murine TN was needed to confer a reproducible protection against lethal sepsis (fig. S5A). Although supplementation of septic mice with sub-physiological doses of murine TN (0.1 mg/kg) conferred reproducible protection (n = 10, N = 2; fig. S5A), administration of murine TN at supra-physiological doses (1.0 mg/kg) did not show any protective effect in sepsis (fig. S5B), suggesting a possibility that TN may exert divergent effects at different concentrations in sepsis.

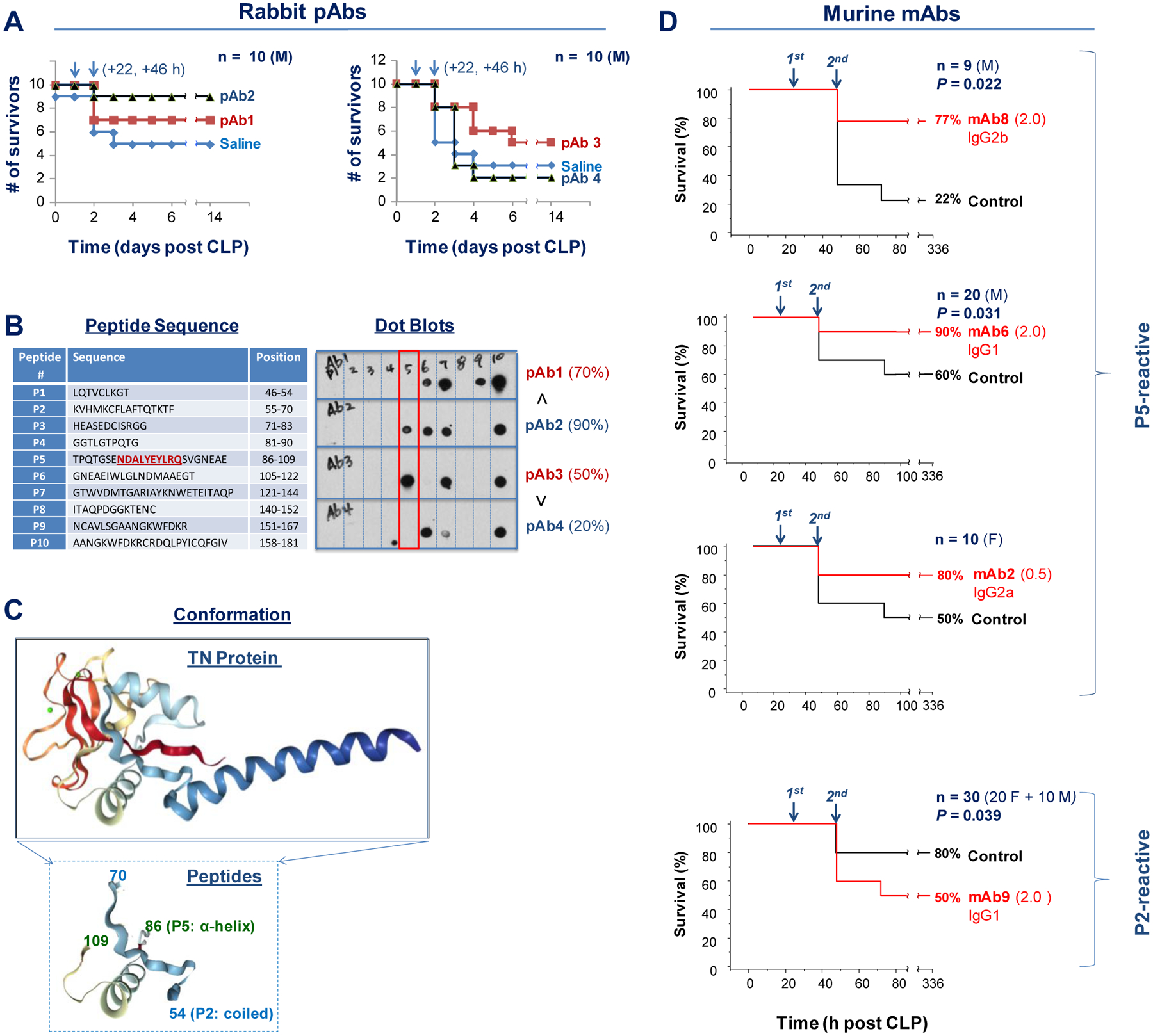

Divergent effects of TN domain-specific polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies (pAbs and mAbs) on lethal sepsis

To further evaluate the role of TN in sepsis, we generated pAbs against murine TN in rabbits, and examined their effects on septic lethality. Notably, the total IgGs purified from two rabbits (pAb2 and pAb3) reproducibly increased animal survival rates in a murine model of lethal sepsis (Fig. 4A), even when the first dose was given at 22 h after CLP. To characterize these pAbs, we screened a library of peptides spanning the entire sequence of human TN (Fig. 4B, Left) to determine the epitope profile of these protective pAbs (Fig. 4B, Right), and found that both protective pAb2 and pAb3 recognized a specific peptide, P5 (Fig. 4B), which forms stable α-helical epitopes either alone in synthetic peptides or being carried by TN proteins (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. Divergent effects of TN domain-specific polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies on septic lethality.

(A) Male (“M”) Balb/C mice (7–10 weeks, 20–25 g) were subjected to CLP-induced sepsis, and intraperitoneally administered total IgGs (40 mg/kg) from each TN-immunized rabbit (#1, #2, #3, and #4) at 22 and 46 h after CLP (arrows). Animal survival was monitored for two weeks. n = 10 animals per group.

(B) Sequences of ten peptides spanning different regions of human TN for antibody epitope mapping of four different rabbit pAbs. The text underlined in red denotes the defined epitope sequence for several P5-reactive protective mAbs. Note that the two protective rabbit antibodies (pAb2 and pAb3) recognized a distinct peptide, P5.

(C) Tertiary structure of human TN protein (upper panel) and its two peptide domains: P2 and P5 (lower panel).

(D) Divergent effects of P5- and P2-reactive mAbs on lethal sepsis. Male (“M”) or female (“F”) Balb/C mice were subjected to lethal sepsis, and intraperitoneally administered different mAbs at indicated doses (0.5 or 2.0 mg/kg) and time points (24 and 48 h after CLP). Animals were monitored for two weeks to ensure long-lasting effects.

We thus immunized Balb/C mice with human TN antigen and generated a panel of hybridoma clones producing mAbs against P5 (four clones) and P2 (three clones) peptides (fig. S6A). Immunoblotting analysis of human and murine serum samples confirmed the specificity of these P2- and P5-specific mAbs (fig. S6B). To further define the epitope sequences of the P5-reactive mAbs, we immunoblotted these mAbs with ten smaller peptides (P5–1 to P5–10, fig. S7A), and found that three of the four P5-binding mAbs reacted with P5–5 peptide (NDALYEYLRQ, fig. S7B). This P5–5 epitope sequence shares 60–70% identity (but still 100% similarity) between human and rodents (fig. S8A), as the variant residues (E vs D; F vs Y; H vs Q; and A vs L) still exhibit similar biochemical properties. Notably, this NDALYEYLRQ epitope sequence is 100% identical between TN proteins in human and many other mammalian species, including baboon, bear, bovine, buffalo, camel, cattle, cougar, elephant, goat, gorilla, hedgehog, horse, lemur, monkey, pig, rabbit, rhinoceros, seal, sheep, and tiger (fig. S8A, S8B), suggesting that these P5–5-reacting mAbs could recognize TN protein in a wide spectrum of mammalian species.

We then explored the therapeutic potential of these mAbs by administering them to septic animals in a delayed fashion – starting at 24 h after CLP. Administration of a P2-specific mAb (mAb9) reproducibly worsened the outcome of lethal sepsis (Fig. 4D, bottom panel), confirming a beneficial role of TN in lethal inflammatory diseases. In a sharp contrast, delayed administration of three P5-reacting mAbs that could recognize both human and murine TN [mAb2 (IgG2a), mAb6 (IgG1), and mAb8 (IgG2b); fig. S6B, fig. S9] similarly and partially rescued mice from lethal sepsis (Fig. 4D). As expected, a P5-reactive mAb5 (IgG1) incapable of binding murine TN (fig. S6B), along with several irrelevant IgG2a or IgG2b isotype controls uniformly failed to confer any protection (fig. S10), confirming that the protective effects of these P5-reactive mAbs were entirely dependent on their murine TN-binding capacities.

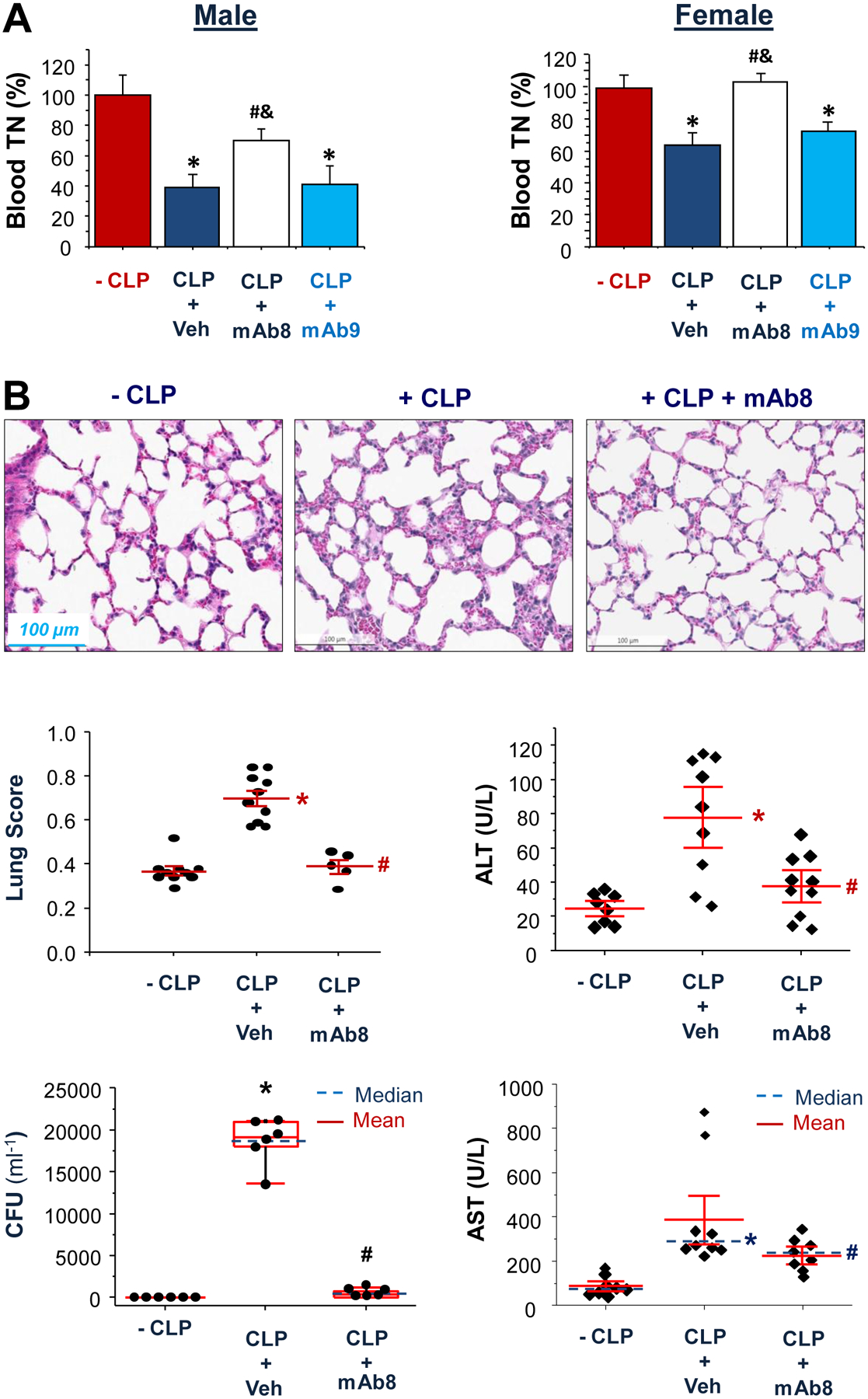

Protective mAb attenuated the sepsis-induced TN depletion, bacterial infection, and tissue injury

To understand how P5-reacting mAbs confer protection against lethal sepsis, we administered TN P5-specific mAb8 and P2-specific mAb9 at 2 and 24 h after CLP, and then determined serum concentrations of TN as well as 62 other cytokines/chemokines at 28 h after CLP. Surprisingly, repeated administration of mAb8, but not mAb9, significantly attenuated the sepsis-induced TN depletion in both male (P = 0.0000287; Fig. 5A, Left; fig. S11) and female animals (P = 0.0000127; Fig. 5A, right). Similarly, the systemic accumulation of IL-6 and KC, two surrogate markers of experimental sepsis (29, 30), was also markedly inhibited by mAb8, but not mAb9, in septic animals (fig. S12). Moreover, repetitive administration of mAb8 significantly attenuated the sepsis-induced lung injury (P = 0.0000459; Fig. 5B), as well as systemic release of liver ALT and AST enzymes (P = 0.000255 and 0.000167, respectively; Fig. 5B), suggesting that TN-specific mAb8 conferred protection partly by attenuating sepsis-induced tissue injury. Notably, mAb8 also markedly reduced blood bacterial count (colony forming units, CFU) at 28 h after CLP (Fig. 5B), indicating that TN-specific protective mAb8 is capable of facilitating pathogen elimination in experimental sepsis.

Fig. 5. TN-specific mAb8 attenuated sepsis-induced TN depletion, bacterial infection, and tissue injury.

(A) Male or female Balb/C mice were subjected to lethal sepsis, and intraperitoneally administered a P5-reacting mAb8 (2.0 mg/kg) or a P2-reacting mAb9 (2.0 mg/kg) at 2 and 24 h after CLP. At 28 h after CLP, animals were euthanized to harvest blood, and serum TN concentrations were determined by Western blotting analysis. *, P < 0.05 versus sham control (“- CLP”); #, P < 0.05 versus vehicle control (“ CLP + Veh”) group; &, P < 0.05 versus “+ CLP + mAb9” group. n = 2 – 4 animals per group.

(B) TN-specific mAb8 (2.0 mg/kg) was given at 2 and 24 h after CLP, and animals were sacrificed at 28 h after CLP to harvest blood and lung tissue for histological analysis, bacterial count, and liver enzyme assays. *, P < 0.05 versus sham “-CLP” group; #, P < 0.05 versus “+ CLP” group. n = 6 – 10 animals per group.

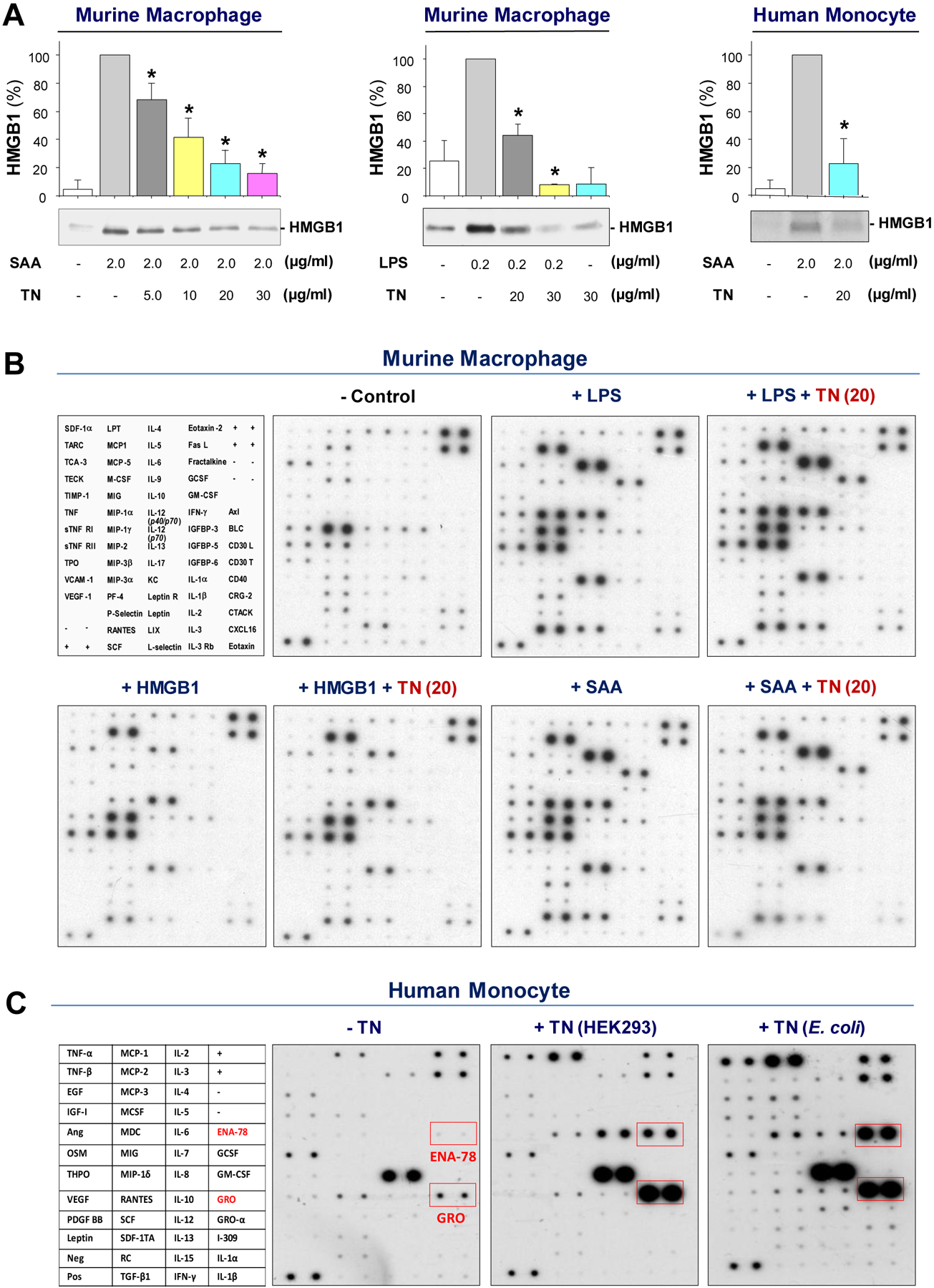

TN selectively inhibited the LPS- and SAA-induced HMGB1 release by capturing and facilitating its endocytosis

To understand the mechanisms underlying the dose-dependent divergent effects of TN in sepsis, we evaluated the possible anti- and pro-inflammatory properties of the recombinant TN proteins in vitro. Highly purified TN protein expressed in either eukaryotes (HEK293 cells) or prokaryotes (E. coli) dose-dependently inhibited the LPS- and SAA-induced HMGB1 release in both murine macrophages (Fig. 6A) and human monocytes (Fig. 6A). This inhibition was specific, because TN did not inhibit the parallel release of other cytokines (including G-CSF, IL-6, IL-12, Fig. 6B) and chemokines (including KC, LIX, MIP-1α, MIP-2, and RANTES, Fig. 6B), even when given at supra-physiological concentrations (20 μg/ml). In primary human monocytes, TN reproducibly and specifically induced the release of GRO (CXCL1 or KC, Fig. 6C) - a surrogate marker of experimental sepsis (29, 30), as well as a potentially beneficial neutrophilic chemokine, ENA-78 (CXCL5, LIX; Fig. 6C) (31).

Fig. 6. TN specifically inhibited the LPS- or SAA-induced HMGB1 release.

(A) Murine peritoneal macrophages or human blood monocytes were stimulated for 16 h with LPS or SAA in the absence or presence of TN at the indicated concentrations. The extracellular HMGB1 concentrations were determined by Western blotting, and expressed as % of maximal stimulation in the presence of LPS or SAA alone. n = 3 per group. *, P< 0.05 versus “+ SAA alone” or “+ LPS alone”.

(B) Thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml), HMGB1 (1.0 μg/ml), or SAA (2.0 μg/ml) in the absence or presence of murine TN (20 μg/ml) for 16 h, and extracellular concentrations of 62 cytokines and chemokines were measured by Cytokine Antibody Arrays.

(C) Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stimulated with recombinant human TN or murine TN (10 μg/ml) for 16 h, and extracellular concentrations of cytokines and chemokines were determined by Cytokine Antibody Arrays.

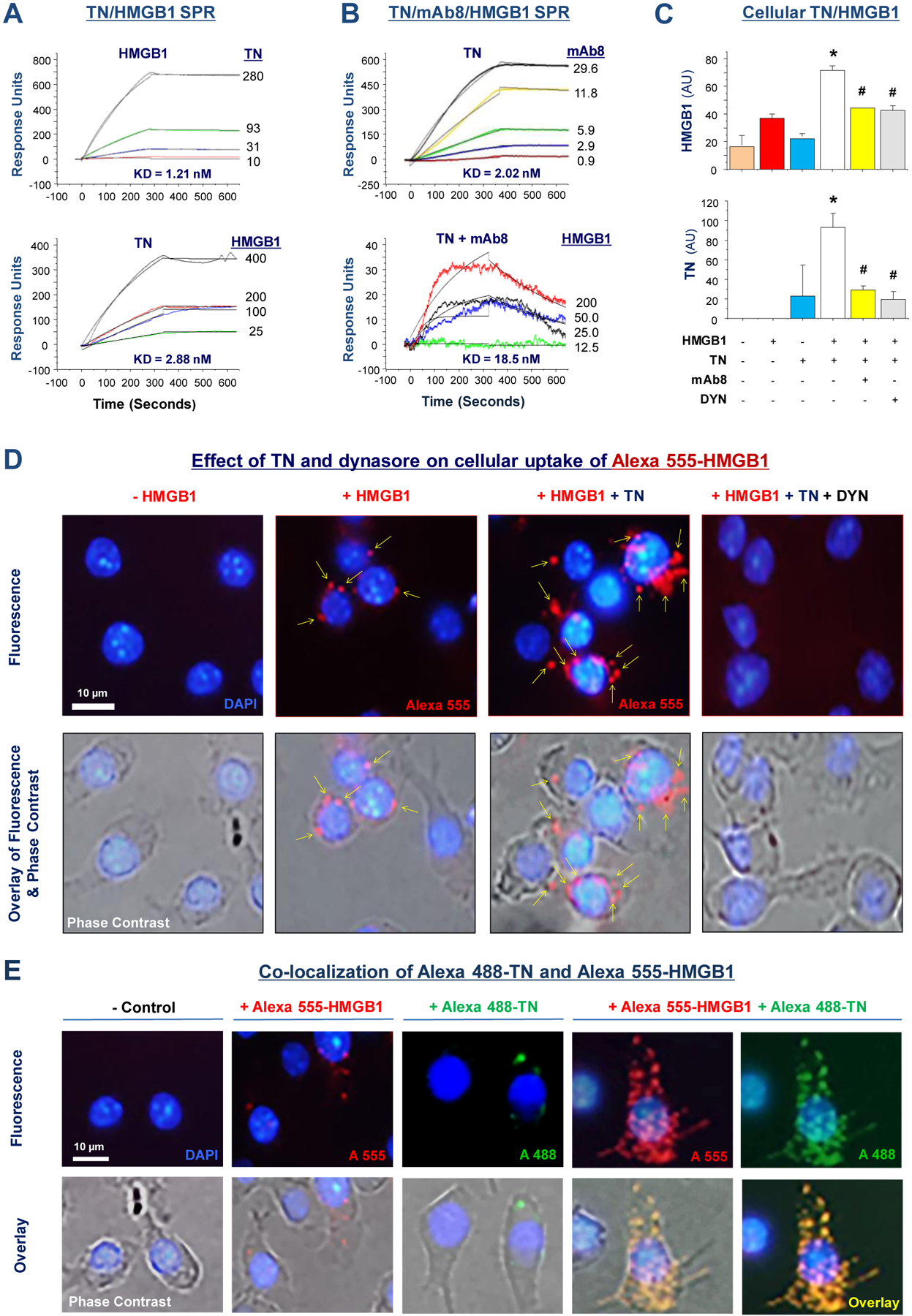

To elucidate the mechanism by which TN selectively inhibited HMGB1 release, we first examined the possible TN/HMGB1 interaction using the Nicoya Lifesciences Open Surface Plasmon Resonance (OpenSPR) technology (Fig. 7A). Regardless of whether TN or HMGB1 was conjugated to the Sensor Chip via His-tag or carboxyl groups, there was a dose-dependent SPR response between TN and HMGB1, with an estimated equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) in the range of 1.21–2.88 nM (Fig. 7A), indicating a strong interaction between these two proteins.

Fig. 7. TN interacted with HMGB1 and reciprocally enhanced the uptake of TN/HMGB1 complexes.

(A) Surface Plasmon Resonance Assay was used to assess TN/HMGB1 interaction by immobilizing highly purified HMGB1 (top) or TN (bottom) protein on the sensor chip, and then applying TN or HMGB1 at different concentrations. The response units were recorded over time to estimate the equilibrium dissociation constant KD.

(B) Highly purified recombinant TN was immobilized on the sensor chip, and mAb8 was applied at indicated concentrations to assess the KD for TN-mAb8 interaction (top). Alternatively, TN-conjugated sensor chip was first pre-treated with mAb8 at 29.6 nM, and then HMGB1 was applied at various concentrations (bottom).

(C) Murine macrophage-like RAW264.7 cells were incubated with HMGB1 (0.5 μg/ml) in the absence or presence of TN (10.0 μg/ml), mAb8 (65.0 μg/ml), or dynasore (8.0 μM) for 2 h. Cellular content of HMGB1 or TN was determined by Western blotting analysis, and expressed as a ratio to β-actin. Bar graph represented average of three samples (n =3) from two independent experiments (N = 2). *, P < 0.05 versus positive control (“+ HMGB1” or “+ TN” alone); #, P < 0.05 versus “+ HMGB1 + TN” group.

(D) Murine macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with Alexa 555-labelled HMGB1 (100 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of recombinant TN (10.0 μg/ml) for 2 h. After extensive washing and fixation, images were acquired. Scale bar: 10 μm. Arrows point to Alexa 555-HMGB1-containing cytoplasmic vesicles.

(E) Fluorescent Alexa 555-labeled HMGB1 (100 ng/ml) and Alexa 488-labelled TN (500 ng/ml) were added to RAW 264.7 cell cultures separately or together, and incubated at 37° for 2 h. After extensive washing and fixation, images were acquired. Scale bar: 10 μm.

To understand how P5-reacting mAbs confer protection against lethal sepsis, we tested whether they interfere with TN/HMGB1 interaction in vitro. When TN was conjugated to the sensor chip, mAb8 exhibited a dose-dependent binding to TN with an estimated KD of ~2.02 nM (Fig. 7B, top). However, when the TN-conjugated sensor chip was pre-treated with mAb8 (29.6 nM), the SPR response signal for subsequent HMGB1 (200 nM) application was reduced by >85% from ~150 AU (Fig. 7A, bottom) to ~35 AU (Fig. 7B, bottom), which was paralleled by an almost 6-fold increase of KD (from 2.88 to 18.5 nM), indicating that mAb8 effectively interrupted TN/HMGB1 interaction. Furthermore, mAb8 markedly prevented the reciprocal enhancement of cellular uptake of HMGB1 (Fig. 7C, top) and TN (Fig. 7C, bottom), indicating that the protective mAbs confer protection possibly through inhibiting TN/HMGB1 interaction and endocytosis.

Consistent with previous reports (7, 10), we observed a basal amount of HMGB1 endocytosis in murine macrophage cultures (Fig. 7C, 7D, 7E). However, at physiological concentrations, TN markedly enhanced HMGB1 cellular uptake (Fig. 7C, 7D), which was prevented by an endocytosis inhibitor, dynasore (Fig. 7C, 7D), implying that TN may have enhanced HMGB1 uptake via endocytosis. Conversely, HMGB1 also enhanced the cellular uptake of TN (Fig. 7C, bottom; Fig. 7E), which was similarly attenuated by dynasore (Fig. 7C), indicating that TN and HMGB1 might be endocytosed simultaneously as a protein complex.

To test this possibility, we labelled HMGB1 and TN with two different fluorescent dyes, and added them simultaneously to macrophage cultures. When they were co-added to macrophage cultures, HMGB1-positive cytoplasmic (red) vesicles almost completely co-localized with TN-positive (green) particles (Fig. 7E), confirming that TN and HMGB1 were likely endocytosed by macrophages as protein complexes. Immunoblotting of cellular proteins with HMGB1- or TN-specific antibodies confirmed the TN-mediated enhancement of HMGB1 cellular uptake, as well as the appearance of additional lower molecular weight bands (marked by empty arrowheads, fig. S13A, S13B) that might be indicative of possible degradation of endocytosed HMGB1 and TN. The high molecular bands (marked by solid arrowheads, fig. S13B) may indicate possible oligomerization of endocytosed TN protein.

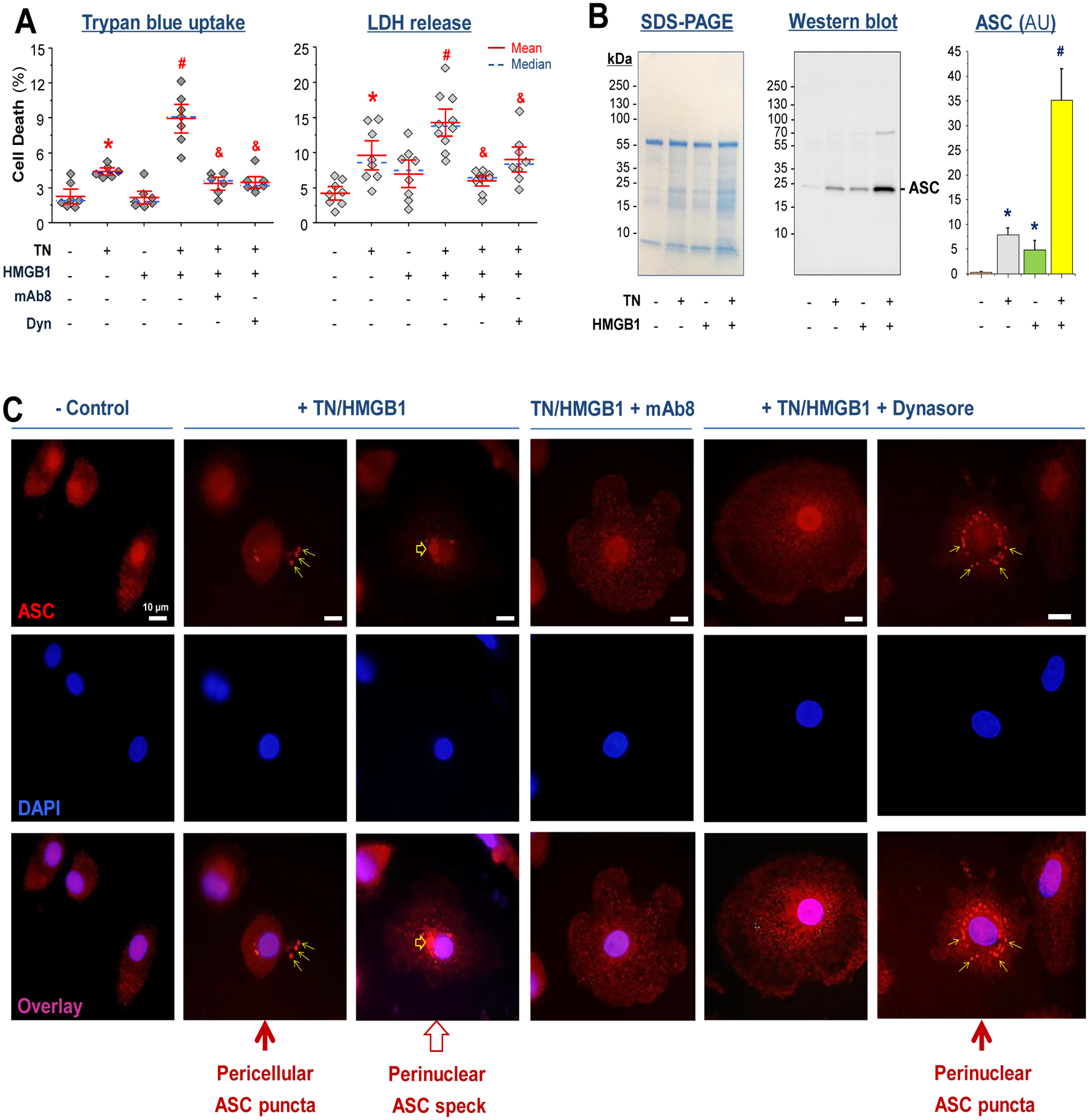

TN-specific protective mAb8 inhibited TN/HMGB1-induced macrophage pyroptosis

As a proinflammatory form of programmed necrosis, pyroptosis is morphologically characterized by the oligomerization of the apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain (ASC) and the resultant integration of a large inflammasome complex (pyroptosome) that eventually triggers the disruption of cytoplasmic membranes (32). Because HMGB1 endocytosis could trigger macrophage pyroptosis (7, 10), we examined whether TN and HMGB1 increased the uptake of trypan blue dye and release of LDH or ASC, a marker for macrophage pyroptosis (33). Consistent with previous findings (7,10), HMGB1 itself did not significantly increase cell death when it was given at a relatively low concentration (0.5 μg/ml, P = 1.0 and 0.08 respectively; Fig. 8A, fig. S14). However, in the presence of TN, HMGB1 induced a significant increase of trypan blue dye uptake (P = 0.00175; Fig. 8A, fig. S14) and LDH release (P = 0.000066; Fig. 8A), which were significantly inhibited by dynasore and mAb8 (P = 0.0027 and 0.00175, P = 0.00002 and 0.0045, respectively; Fig. 8A, fig. S14). Similarly, the co-addition of both proteins triggered an additive enhancement of ASC release (Fig. 8B), suggesting that TN/HMGB1 interacts to facilitate their endocytosis to trigger macrophage pyroptosis. Indeed, when TN and HMGB1 were co-added to human macrophage cultures, they induced translocation of nuclear ASC to cytoplasmic regions, where ASC either aggregated into minute puncta that appeared to be secreted through microvesicle shedding (Fig. 8C, narrow arrows), or aggregated into a larger focus or speck (pyroptosome) that would trigger pyroptosis (Fig. 8C, wide arrow). Pretreatment with dynasore (20 μM) or mAb8 (40 μg/ml) prevented the TN/HMGB1-induced cytoplasmic ASC translocation or aggregation into large ASC specks in ten randomly selected microscopic fields of three separate samples (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8. TN and HMGB1 cooperate to induce macrophage cell death.

(A) Thioglycolate-elicited murine peritoneal macrophages were treated with TN (10 μg/ml) in the absence or presence of HMGB1 (0.5 μg/ml), TN-specific mAb8 (65.0 μg/ml), or dynasore (10.0 μM) for 16 h, and cell viability was assessed by trypan blue dye exclusion or LDH release assay. *, P < 0.05 versus negative control; #, P <0.05 versus “+ TN” or “+ HMGB1” alone; &, P < 0.05 versus positive control “+ TN + HMGB1” group, n = 6 – 10 per group.

(B) Murine peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with TN (10 μg/ml) in the absence or presence of HMGB1 (1.0 μg/ml) for 16 h, and the cell-conditioned medium was assayed for ASC release by Western blotting analysis. SDS-PAGE gel indicated equivalent sampling loading. Bar graph represented average of three samples (n = 3) from two independent experiments (N = 2). *, P < 0.05 versus negative controls (“- HMGB1 - TN”); #, P < 0.05 versus positive control (“+ HMGB1” or “ + TN” alone).

(C) Differentiated human macrophages were stimulated with HMGB1 (1.0 μg/ml) and TN (10.0 μg/ml) in the absence or presence of TN-specific mAb (40 μg/ml) or dynasore (20.0 μM) for 16 h. Subsequently, cells were immunostained with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-ASC IgGs. Scale bars: 10 μm. Narrow arrows point to minute ASC puncta; Wide arrow points to a larger ASC speck.

DISCUSSION

Throughout evolution, mammals have developed multiple mechanisms to regulate innate immune functions. In the present study, we report a role for TN in capturing HMGB1 and facilitating its cellular uptake via possible endocytosis of TN/HMGB1 complexes. The reciprocal enhancement of HMGB1/TN endocytosis may promote macrophage pyroptosis and possible immunosuppression that may compromise the host’s ability to eradicate microbial infections (12, 13). Moreover, we have discovered a panel of TN domain-specific monoclonal antibodies that effectively prevented TN/HMGB1 interaction and their cellular uptake, thereby attenuating the sepsis-induced TN depletion and animal lethality in pre-clinical settings. Because these protective mAbs recognize a distinct amino acid sequence with 100% identity between humans and many other mammalian species, they hold promising potential for the clinical management of inflammatory diseases. Moreover, our current findings revealed an antibody strategy to preserve a beneficial protein by preventing its harmful interaction with HMGB1, a pathogenic mediator of lethal sepsis.

Upon active secretion by innate immune cells or passive release by somatic cells such as hepatocytes, extracellular HMGB1 binds a family of cell surface receptors including the Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4) (34) and the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products (RAGE) (35) to induce the expression and production of various cytokines and chemokines, or to trigger macrophage pyroptosis if HMGB1 is internalized via RAGE-receptor-mediated endocytosis (7, 10). As a highly charged protein, HMGB1 could bind to many negatively charged pathogen-associated molecular patterns [PAMPs, such as CpG-DNA or lipopolysaccharide (LPS)] to facilitate their cellular uptake via RAGE-receptor-mediated endocytosis. Upon reaching acidic endosomal and lysosomal compartments (pH 5.4 – 6.2) near HMGB1’s isoelectric pH (pI = pH 5.6), HMGB1 becomes neutrally charged, and thus sets free its cargos (7) to their cytoplasmic TLR9 (35) and Caspase-11 receptors (7). Consequently, HMGB1 not only augments the PAMP-induced inflammation (35), but also promotes the PAMP-induced pyroptosis (7), resulting in a dysregulated inflammatory response as well as macrophage depletion and possible immunosuppression during sepsis (fig. S15).

In contrast to exogenous PAMPs, HMGB1 also binds endogenous proteins such as haptoglobin and C1q, but triggers anti-inflammatory responses via distinct signaling pathways (36, 37). Here we have uncovered an important role for another endogenous protein, TN, in capturing HMGB1 to enhance the endocytosis of TN/HMGB1 complexes without impairing HMGB1’s cytokine/chemokine-inducing capacities. The reciprocal enhancement of TN/HMGB1 endocytosis was associated with an increase of macrophage cell death and release of ASC, a marker of macrophage pyroptosis (33). TN was capable of stimulating human monocytes to release: 1) GRO/CXCL1/KC, a surrogate marker of experimental sepsis (29, 30) associated with inflammasome activation and pyroptosis (38); and 2) ENA-78/CXCL5/LIX, a neutrophilic chemokine possibly beneficial in sepsis (31). Thus, TN likely plays two seemingly conflicting roles in sepsis. On the one hand, TN promoted HMGB1 endocytosis and macrophage pyroptosis, which likely contributes to immunosuppression in sepsis (fig. S15). On the other hand, TN selectively attenuated the release of a pathogenic sepsis mediator (HMGB1) and induced the secretion of a potentially beneficial chemokine (ENA-78/CXCL5/LIX) (31).

The mechanism by which TN-specific mAbs rescue animals from lethal sepsis remains an exciting subject for future investigation. At least in part, it might be attributable to the effective attenuation of sepsis-induced TN depletion, which was likely pathogenic in sepsis for several reasons. First, genetic disruption of TN expression rendered animals more susceptible to septic insults. Second, circulating TN was depleted under pathological conditions during experimental and clinical sepsis. Third, supplementation of septic animals with exogenous TN at sub-physiological doses conferred marked protection. Finally, a panel of P5-reacting mAbs capable of rescuing animals from lethal sepsis uniformly attenuated the sepsis-induced TN depletion. These TN-specific protective mAbs prevented the sepsis-induced TN depletion, possibly through disrupting TN/HMGB1 interaction and thereby preventing their endocytotic degradation. Notably, our current findings echoed with a recent report that an HMGB1-neutralizing mAb (2G7) similarly inhibited HMGB1 endocytosis (39), thereby conferring protection against lethal sepsis possibly by attenuating cellular HMGB1 uptake.

There are a number of limitations to the present study: 1) we have not yet obtained sufficient numbers of age-matched critically ill patients who died of severe sepsis or septic shock at comparable ages, and could thus not perform a statistical comparison of plasma TN concentrations between age-matched sepsis survivors and non-survivors; 2) it remains elusive whether TN domain-specific mAbs confer protection by altering ENA-78/CXCL5/LIX expression in sepsis; 3) it is not yet known what exact macrophage cell receptors are involved in the endocytosis of TN/HMGB1 complexes; 4) it is unclear whether TN-specific mAbs similarly affect TN interaction with other proteins (for example, plasminogen) that may affect sepsis-induced dysregulated coagulopathy; 5) although TN/HMGB1 complexes might be readily engulfed by innate immune cells, it should still be possible and important to characterize the TN/HMGB1 complexes in patients’ plasma samples. However, the discovery of mAbs capable of disrupting TN/HMGB1 interaction and endocytosis has suggested an exciting possibility of exploring antibody strategies to fight against inflammatory diseases. It would be exciting to translate these pre-clinical findings into clinical applications through the use of humanized TN-specific mAbs capable of preventing its undesired interaction with pathogenic mediators that could cause macrophage pyroptosis and immunosuppression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The aim of this study was to assess the pathogenic changes of plasma TN concentrations in critically ill patients with sepsis or septic shock, and use TN domain-specific monoclonal antibodies to prevent TN depletion in the pre-clinical setting. For the clinical investigation, blood samples were obtained from normal healthy controls and patients with sepsis or septic shock recruited to the Northwell Health System, and their plasma TN concentrations were assessed by immunoassays. Sample sizes were purely based on availability, and no blinding or randomization was applied for this non-interventional observation. For the pre-clinical study, animals were randomly assigned to different experimental groups, and treated with recombinant TN or specific antibodies at the indicated dosing regiments. The outcomes included animal survival rates, blood bacterial counts, lung histology scores, as well as blood concentrations of liver-derived enzymes. Lung histology scores were collected under blinded experimental conditions. Study design and sample sizes used for each experiment are provided in the figure legends. No data, including outlier values, were excluded. Primary data are reported in data file S1. All reagent sources are listed in table S1.

Cell culture

Primary peritoneal macrophages were isolated from male Balb/c mice (7–8 wks, 20–25 g) at 3 days after intraperitoneal injection of 2 ml thioglycolate broth (4%) as previously described (40, 41, 42). Human blood was purchased from the New York Blood Center (Long Island City, NY, USA), and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (HuPBMCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation through Ficoll (Ficoll-Paque PLUS) as previously described (43–45). To differentiate into macrophages, human PBMCs were cultured in the presence of human M-CSF (20 ng/mL) for 5–6 days. Murine macrophages, human monocytes (HuBPMCs), and differentiated human macrophages were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% FBS or 10% human serum. When they reached 70–80% confluence, adherent cells were gently washed with, and immediately cultured in, OPTI-MEM I before stimulating with crude LPS, purified SAA, HMGB1, in the absence or presence of human TN. The intracellular and extracellular concentrations of HMGB1, TN, or various other cytokines/chemokines were determined by Western blotting analysis or Cytokine Antibody Arrays as previously described (40, 46–48). Alternatively, murine or human macrophages were stimulated with HMGB1 (0.5 – 1.0 μg/ml) and TN (10 μg/ml) either alone or concurrently in the absence or presence of TN-specific mAb8 (65.0 μg/ml) or dynasore (10.0 μM) for 16 h, and cell viability or the formation of ASC speck were examined 16 h later.

Cell viability

Cell viability was evaluated by the trypan blue exclusion method, which distinguished the unstained viable cells from nonviable cells that taken up the dye to exhibit a distinctive blue color. Phase contrast images of multiple fields were randomly captured, and the percentage of trypan blue-stained cells was calculated. The released LDH in the culture medium was measured using an LDH Assay Kit (Cat. # L7572, Pointe Scientific Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The optical density was measured at 340 nm using the ELISA plate reader, and the LDH content was expressed as the percentage of the maximal LDH release in the presence of 2% Triton X-100.

Immunofluorescence

After inflammasome activation, ASC polymerizes to form a large singular structure termed the ASC “speck” (32), which could be visualized by immunofluorescence of endogenous ASC using fluorescence-labeled ASC antibodies. Briefly, after stimulation with TN and HMGB1 in the absence or presence of TN-specific mAb8 or dynasore for 16 h, differentiated human macrophages were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min. After blocking with 5% albumin in 0.1% Triton X-100 (in 1× PBS) for 30 min, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated ASC Antibody (1.5:1000) for 1 h, and then washed three times with 0.1% Triton X-100 (in 1× PBS). Afterwards, coverslips were mounted upside down on microscope slides, and images were acquired using the Olympus IX51 Inverted Fluorescence & Phase Contrast Tissue Culture Microscope.

Clinical characterization of septic patients

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research (FIMR), and endorsed by written informed consent from all participants providing blood samples. Blood samples (5.0 ml) were collected from 33 healthy control subjects, 31 patients with sepsis, and 14 patients with septic shock. Patients were diagnosed with sepsis or septic shock as per the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference definitions of Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-2 definition) (49). The first cohort of 31 patients with sepsis was recruited to the North Shore University Hospital (NSUH) between 2010–2011 (listed as the “NS-P” in data file S1). The second cohort of 14 patients with septic shock was recruited to NSUH and the Long Island Jewish Medical Center between 2018–2019 (listed as “LIQ/H-P” in data file S1). In addition, we obtained 11 healthy control plasma samples from the Discovery Life Science Open Access Biorepository. The plasma TN concentrations were determined by Western blotting and ELISA using human CLEC3B/tetranectin ELISA kit (Cat. # ELH-CLEC#B-1, RayBiotech) with reference to purified recombinant human TN at various dilutions.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

To identify the 20-kDa band that was depleted in septic patients, serum samples of healthy controls and septic patients were resolved by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis, and the corresponding 20-kDa band was subjected to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis as previously described (47). Briefly, the 20-kDa band was excised from the SDS-PAGE gel, and subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion. The mass of the tryptic peptides was measured by MALDI-TOF-MS and then subjected to peptide mass fingerprinting database analysis to identify the 20-kDa protein (“P20”).

Open Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

We used the Nicoya Lifesciences gold-nanoparticle-based Open Surface Plasmon Resonance (OpenSPR) technology to characterize protein-protein interactions following the manufacturer’s instructions. For instance, highly purified recombinant HMGB1 or TN protein was immobilized on the amine sensor chip (Cat. # SEN-Au-100–10-AMINE) or NTA sensor chip (Cat. # SEN-Au-100–10-NTA), respectively, and TN, mAb, or HMGB1 was applied at different concentrations. To determine the binding affinities of mAbs to human or murine TN, highly purified human or murine TN was immobilized on the NTA sensor chip (Cat. # SEN-Au-100–10-NTA), and various mAbs were applied at various concentrations. The response units were recorded over time, and the binding affinity was estimated as the equilibrium dissociation constant KD using the Trace Drawer Kinetic Data Analysis v.1.6.1. (Nicoya Lifesciences).

Cytokine Antibody Array

Murine Cytokine Antibody Arrays (Cat. No. M0308003, RayBiotech Inc.), which simultaneously detect 62 cytokines on one membrane, were used to measure relative cytokine concentrations in macrophage-conditioned culture medium or animal serum as described previously (40, 50). Human Cytokine Antibody C3 Arrays (Cat. No. AAH-CYT-3–4), which detect 42 cytokines on one membrane, were used to determine cytokine concentrations in human monocyte-conditioned culture medium as previously described (41, 44).

Generation of anti-TN polyclonal antibodies and monoclonal antibodies

Polyclonal antibodies were generated in Female New Zealand White Rabbits at the Covance Inc. (Princeton, New Jersey, USA) using recombinant murine TN in combination with Freund’s complete adjuvant following standard procedures. Blood samples were collected in 3-week cycles of immunization and bleeding, and the antibody titers were determined by indirect TN ELISA. Total IgGs were purified from the serum using Protein A affinity column. Briefly, rabbit serum was pre-buffered with PBS and slowly loaded onto the Protein A column to allow sufficient binding of IgGs. After washing with 1×PBS to remove unbound serum components, the IgGs were eluted with acidic buffer (0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.8), and then immediately dialyzed into 1×PBS buffer at 4°C overnight.

The monoclonal antibodies were generated in Balb/C and C57BL/6 mice at the GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA) using highly purified human TN following standard procedures. Blood samples were collected in 2-week cycles of immunization and bleeding, and serum titers were assessed by indirect ELISA. After four immunizations, mouse splenocytes were harvested, fused with mouse Sp2/0 myeloma cell line, and screened for antibody-producing hybridomas by indirect ELISA, dot blotting, and Western blotting analysis. After limiting dilution, purified hybridoma clones were generated to produce mAbs following standard procedures. For V-region sequencing, five independent hybridoma preparations for each clone were used to isolate total RNA, reverse transcribed into cDNA. The heavy and light chain variable regions (VR) were amplified by PCR, and subcloned into a selectable bacterial shuttle vector for DNA sequencing analysis of the complementarity-determining regions (CDR) of each mAb.

Animal model of lethal endotoxemia and sepsis

This study was conducted in accordance with policies of the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approved by the IACUC of the FIMR. To evaluate the role of TN in lethal sepsis, Balb/C mice (male or female, 7–8 weeks old, 20–25 g) were subjected to lethal endotoxemia or sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) as previously described (51, 52). Briefly, the cecum of Balb/C mice was ligated at 5.0 mm from the cecal tip, and then punctured once with a 22-gauge needle. At 30 min after CLP, all animals were given a subcutaneous dose of imipenem/cilastatin (0.5 mg/mouse) (Primaxin, Merck & Co., Inc.) and resuscitation with normal sterile saline solution (20 ml/kg). Recombinant TN or anti-TN polyclonal or monoclonal IgGs were intraperitoneally administered to endotoxemic or septic mice at the indicated doses and time points, and animal survival rates were monitored for up to two weeks. To evaluate the role of TN in lethal sepsis, breeding pairs of the heterozygous TN (also called “CLCE3B”) knock-out (KO) mice (on C57BL/6J genetic background) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Stock No. 027554) and bred to produce homozygous TN KO as well as wild-type littermates. Age- and sex-matched wild-type (WT) or TN knockout (KO) C57BL/6J mice were then subjected to CLP sepsis, and animal survival rates were compared between wild-type and TN KO mice for up to two weeks.

Tissue injury

Lung tissues were collected at 24 h or 28 h after the onset of sepsis and stored in 10% formalin before fixation in paraffin. The fixed tissue was then sectioned (5 μm) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Tissue injury was assessed in a blinded fashion using a semi-quantitative scoring system developed by the American Thoracic Society. Briefly, histological lung injury was scored based on the presence of infiltrated inflammatory cells in the alveolar and interstitial spaces, the presence of hyaline membranes and proteinaceous debris within airspaces, and alveolar septal thickening, according to the following definition: 0, no injury; 1, moderate injury; 2, severe injury. Using a weighted equation with a maximum score of 100 per field, the parameter scores were calculated and then averaged as the final lung injury score in each experimental group. At 28 h after CLP, animals were euthanized to harvest blood to measure serum concentrations of hepatic injury markers such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) using commercial kits (Cat. # A7561 and Cat. # A7526, company, Pointe Scientific Inc.) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA-seq analysis

At 24 h after the onset of sepsis, various tissues were harvested to isolate total RNA, and the expression of all transcripts in wild-type or TN KO mice was assessed by RNA Sequencing (GENEWIZ). Gene ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis were applied to analyze the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by using String online tools (https://string-db.org/cgi/input.pl). Differential expression analysis was performed using the Wald test (DESeq2) to generate P-values and log2 fold changes. Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change > 2 were defined as differentially expressed.

Colony-forming units

Bacterial counts were performed on aseptically harvested blood samples after serial dilution in sterile PBS and culture on tryptic soy agar plates supplemented with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson). After incubation at 37°C for 24–48 h, the colony-forming units (CFUs) were counted.

Peptide dot blotting

A library of synthetic peptides corresponding to different regions of human TN sequence were synthesized and spotted (1.0 μg in 2.5 μl) onto nitrocellulose membrane (Thermo Scientific, Cat No. 88013). Subsequently, the membrane was probed with IgGs from different rabbits or murine hybridomas following a standard protocol.

Statistical analysis

All data were assessed for normality by the Shapiro-Wilk test before conducting appropriate statistical tests between groups. The comparison of two independent samples was assessed by the Student’s t test and the Mann-Whitney test for Gaussian and non-Gaussian distributed samples, respectively. For comparison among multiple groups with normal data distribution, the differences were analyzed by one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Fisher Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. For comparison among multiple groups with non-normal (skewed) distribution, the statistical differences were evaluated with the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA test. For survival studies, the Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare the differences in mortality rates between groups with the nonparametric log-rank post hoc test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank a former lab member, Dr. Wei Li for the initial characterization of tetranectin as a protein depleted in septic patients who died of sepsis, the subsequent epitope mapping of rabbit polyclonal antibodies against murine tetranectin, as well as the finding of ASC release by tetranectin-stimulated peritoneal macrophages. We also thank Dr. Guoqiang Bao for testing the protective efficacy of recombinant human tetranectin in animal model of sepsis, and thank Dr. Junhwan Kim for providing 16 plasma samples to the healthy control group.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01GM063075 (to HW) and R01AT005076 (to HW).

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

H.W., J.L., K.J.T. and W.C. are co-inventors of patent applications entitled “Use of tetranectin and peptide agonists to treat inflammatory diseases” (Application #16/617,811) and “Tetranectin-targeting monoclonal antibodies to fight against lethal sepsis and other pathologies.” (Application 62/885,890). All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, and Angus DC, “The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3),” JAMA. 315, 801–810 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen J, Vincent JL, Adhikari NK, Machado FR, Angus DC, Calandra T, Jaton K, Giulieri S, Delaloye J, Opal S, Tracey K, van der Poll T, and Pelfrene E, “Sepsis: a roadmap for future research,” Lancet Infect. Dis 15, 581–614 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotchkiss RS and Karl IE, “The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis,” N Engl J Med 348, 138–150 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, and Tracey KJ, “HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice,” Science 285, 248–251 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang H, Ochani M, Li J, Qiang X, Tanovic M, Harris HE, Susarla SM, Ulloa L, Wang H, DiRaimo R, Czura CJ, Wang H, Roth J, Warren HS, Fink MP, Fenton MJ, Andersson U, and Tracey KJ, “Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 296–301 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin S, Wang H, Yuan R, Li H, Ochani M, Ochani K, Rosas-Ballina M, Czura CJ, Huston JM, Miller E, Lin X, Sherry B, Kumar A, Larosa G, Newman W, Tracey KJ, and Yang H, “Role of HMGB1 in apoptosis-mediated sepsis lethality,” J Exp. Med 203, 1637–1642 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng M, Tang Y, Li W, Wang X, Zhang R, Zhang X, Zhao X, Liu J, Tang C, Liu Z, Huang Y, Peng H, Xiao L, Tang D, Scott MJ, Wang Q, Liu J, Xiao X, Watkins S, Li J, Yang H, Wang H, Chen F, Tracey KJ, Billiar TR, and Lu B, “The Endotoxin Delivery Protein HMGB1 Mediates Caspase-11-Dependent Lethality in Sepsis,” Immunity. 49, 740–753 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert SM, Sjodin H, Fink MP, and Aneja RK, “Preconditioning with high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) induces lipoteichoic acid (LTA) tolerance,” J. Immunother 33, 663–671 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aneja RK, Tsung A, Sjodin H, Gefter JV, Delude RL, Billiar TR, and Fink MP, “Preconditioning with high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) induces lipopolysaccharide (LPS) tolerance,” J. Leukoc. Biol 84, 1326–1334 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J, Jiang Y, Wang J, Shi X, Liu Q, Liu Z, Li Y, Scott MJ, Xiao G, Li S, Fan L, Billiar TR, Wilson MA, and Fan J, “Macrophage endocytosis of high-mobility group box 1 triggers pyroptosis,” Cell Death. Differ 21, 1229–1239 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregoire M, Tadie JM, Uhel F, Gacouin A, Piau C, Bone N, Le TY, Abraham E, Tarte K, and Zmijewski JW, “Frontline Science: HMGB1 induces neutrophil dysfunction in experimental sepsis and in patients who survive septic shock,” J. Leukoc. Biol 101, 1281–1287 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wild CA, Bergmann C, Fritz G, Schuler P, Hoffmann TK, Lotfi R, Westendorf A, Brandau S, and Lang S, “HMGB1 conveys immunosuppressive characteristics on regulatory and conventional T cells,” Int. Immunol 24, 485–494 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel VS, Sitapara RA, Gore A, Phan B, Sharma L, Sampat V, Li J, Yang H, Chavan SS, Wang H, Tracey KJ, and Mantell LL, “HMGB1 Mediates Hyperoxia-Induced Impairment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clearance and Inflammatory Lung Injury in Mice,” Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemmensen I, Petersen LC, and Kluft C, “Purification and characterization of a novel, oligomeric, plasminogen kringle 4 binding protein from human plasma: tetranectin,” Eur. J. Biochem 156, 327–333 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorensen CB, Berglund L, and Petersen TE, “Cloning of a cDNA encoding murine tetranectin,” Gene 152, 243–245 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berglund L and Petersen TE, “The gene structure of tetranectin, a plasminogen binding protein,” FEBS Lett. 309, 15–19 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wewer UM, Iba K, Durkin ME, Nielsen FC, Loechel F, Gilpin BJ, Kuang W, Engvall E, and Albrechtsen R, “Tetranectin is a novel marker for myogenesis during embryonic development, muscle regeneration, and muscle cell differentiation in vitro,” Dev. Biol 200, 247–259 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen BA, McNair P, Hyldstrup L, and Clemmensen I, “Plasma tetranectin in healthy male and female individuals, measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay,” J. Lab Clin. Med 110, 612–617 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorentsen RH, Graversen JH, Caterer NR, Thogersen HC, and Etzerodt M, “The heparin-binding site in tetranectin is located in the N-terminal region and binding does not involve the carbohydrate recognition domain,” Biochem. J 347 Pt 1, 83–87 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graversen JH, Lorentsen RH, Jacobsen C, Moestrup SK, Sigurskjold BW, Thogersen HC, and Etzerodt M, “The plasminogen binding site of the C-type lectin tetranectin is located in the carbohydrate recognition domain, and binding is sensitive to both calcium and lysine,” J. Biol. Chem 273, 29241–29246 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graversen JH, Sigurskjold BW, Thogersen HC, and Etzerodt M, “Tetranectin-binding site on plasminogen kringle 4 involves the lysine-binding pocket and at least one additional amino acid residue,” Biochemistry 39, 7414–7419 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kluft C, Jie AF, Los P, de WE, and Havekes L, “Functional analogy between lipoprotein(a) and plasminogen in the binding to the kringle 4 binding protein, tetranectin,” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 161, 427–433 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westergaard UB, Andersen MH, Heegaard CW, Fedosov SN, and Petersen TE, “Tetranectin binds hepatocyte growth factor and tissue-type plasminogen activator,” Eur. J. Biochem 270, 1850–1854 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wewer UM, Ibaraki K, Schjorring P, Durkin ME, Young MF, and Albrechtsen R, “A potential role for tetranectin in mineralization during osteogenesis,” J. Cell Biol 127, 1767–1775 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iba K, Durkin ME, Johnsen L, Hunziker E, Damgaard-Pedersen K, Zhang H, Engvall E, Albrechtsen R, and Wewer UM, “Mice with a targeted deletion of the tetranectin gene exhibit a spinal deformity,” Mol. Cell Biol 21, 7817–7825 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang ES, Zhang XP, Yao HB, Wang G, Chen SW, Gao WW, Yao HJ, Sun YR, Xi CH, and Ji YD, “Tetranectin knockout mice develop features of Parkinson disease,” Cell Physiol Biochem. 34, 277–287 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iba K, Hatakeyama N, Kojima T, Murata M, Matsumura T, Wewer UM, Wada T, Sawada N, and Yamashita T, “Impaired cutaneous wound healing in mice lacking tetranectin,” Wound. Repair Regen 17, 108–112 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iba K, Abe Y, Chikenji T, Kanaya K, Chiba H, Sasaki K, Dohke T, Wada T, and Yamashita T, “Delayed fracture healing in tetranectin-deficient mice,” J. Bone Miner. Metab 31, 399–408 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osuchowski MF, Welch K, Siddiqui J, and Remick DG, “Circulating cytokine/inhibitor profiles reshape the understanding of the SIRS/CARS continuum in sepsis and predict mortality,” J Immunol. 177, 1967–1974 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heuer JG, Sharma GR, Gerlitz B, Zhang T, Bailey DL, Ding C, Berg DT, Perkins D, Stephens EJ, Holmes KC, Grubbs RL, Fynboe KA, Chen YF, Grinnell B, and Jakubowski JA, “Evaluation of protein C and other biomarkers as predictors of mortality in a rat cecal ligation and puncture model of sepsis,” Crit Care Med. 32, 1570–1578 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mei J, Liu Y, Dai N, Favara M, Greene T, Jeyaseelan S, Poncz M, Lee JS, and Worthen GS, “CXCL5 regulates chemokine scavenging and pulmonary host defense to bacterial infection,” Immunity. 33, 106–117 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dick MS, Sborgi L, Ruhl S, Hiller S, and Broz P, “ASC filament formation serves as a signal amplification mechanism for inflammasomes,” Nat. Commun 7, doi: 10.1038/ncomms11929 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franklin BS, Bossaller L, De ND, Ratter JM, Stutz A, Engels G, Brenker C, Nordhoff M, Mirandola SR, Al-Amoudi A, Mangan MS, Zimmer S, Monks BG, Fricke M, Schmidt RE, Espevik T, Jones B, Jarnicki AG, Hansbro PM, Busto P, Marshak-Rothstein A, Hornemann S, Aguzzi A, Kastenmuller W, and Latz E, “The adaptor ASC has extracellular and ‘prionoid’ activities that propagate inflammation,” Nat. Immunol 15, 727–737 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu M, Wang H, Ding A, Golenbock DT, Latz E, Czura CJ, Fenton MJ, Tracey KJ, and Yang H, “HMGB1 SIGNALS THROUGH TOLL-LIKE RECEPTOR (TLR) 4 AND TLR2,” Shock 26, 174–179 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao SY, Chen B, Senthil K, Wu H, Parroche P, Drabic S, Golenbock D, Sirois C, Hua J, An LL, Audoly L, La Rosa G, Bierhaus A, Naworth P, Marshak-Rothstein A, Crow MK, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Kiener PA, and Coyle AJ, “Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE,” Nat. Immunol 8, 487–496 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang H, Wang H, Levine YA, Gunasekaran MK, Wang Y, Addorisio M, Zhu S, Li W, Li J, de Kleijn DP, Olofsson PS, Warren HS, He M, Al-Abed Y, Roth J, Antoine DJ, Chavan SS, Andersson U, and Tracey KJ, “Identification of CD163 as an antiinflammatory receptor for HMGB1-haptoglobin complexes,” JCI. Insight 1, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Son M, Porat A, He M, Suurmond J, Santiago-Schwarz F, Andersson U, Coleman TR, Volpe BT, Tracey KJ, Al-Abed Y, and Diamond B, “C1q and HMGB1 reciprocally regulate human macrophage polarization,” Blood. 128, 2218–2228 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kovarova M, Hesker PR, Jania L, Nguyen M, Snouwaert JN, Xiang Z, Lommatzsch SE, Huang MT, Ting JP, and Koller BH, “NLRP1-dependent pyroptosis leads to acute lung injury and morbidity in mice,” J. Immunol 189, 2006–2016 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang H, Liu H, Zeng Q, Imperato GH, Addorisio ME, Li J, He M, Cheng KF, Al-Abed Y, Harris HE, Chavan SS, Andersson U, and Tracey KJ, “Inhibition of HMGB1/RAGE-mediated endocytosis by HMGB1 antagonist box A, anti-HMGB1 antibodies, and cholinergic agonists suppresses inflammation,” Mol. Med 25, 13–0081 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li W, Bao G, Chen W, Qiang X, Zhu S, Wang S, He M, Ma G, Ochani M, Al-Abed Y, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Wang P, D’Angelo J, and Wang H, “Connexin 43 Hemichannel as a Novel Mediator of Sterile and Infectious Inflammatory Diseases,” Sci. Rep 8, 166–18452 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li W, Ashok M, Li J, Yang H, Sama AE, and Wang H, “A Major Ingredient of Green Tea Rescues Mice from Lethal Sepsis Partly by Inhibiting HMGB1,” PLoS ONE 2, e1153 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Li W, Zhu S, Jundoria A, Li J, Yang H, Fan S, Wang P, Tracey KJ, Sama AE, and Wang H, “Tanshinone IIA sodium sulfonate facilitates endocytic HMGB1 uptake,” Biochem. Pharmacol 84, 1492–1500 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen G, Li J, Ochani M, Rendon-Mitchell B, Qiang X, Susarla S, Ulloa L, Yang H, Fan S, Goyert SM, Wang P, Tracey KJ, Sama AE, and Wang H, “Bacterial endotoxin stimulates macrophages to release HMGB1 partly through CD14- and TNF-dependent mechanisms.,” J Leukoc. Biol 76, 994–1001 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li W, Li J, Ashok M, Wu R, Chen D, Yang L, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Wang P, Sama AE, and Wang H, “A cardiovascular drug rescues mice from lethal sepsis by selectively attenuating a late-acting proinflammatory mediator, high mobility group box 1,” J. Immunol 178, 3856–3864 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rendon-Mitchell B, Ochani M, Li J, Han J, Wang H, Yang H, Susarla S, Czura C, Mitchell RA, Chen G, Sama AE, Tracey KJ, and Wang H, “IFN-gamma Induces High Mobility Group Box 1 Protein Release Partly Through a TNF-Dependent Mechanism,” J Immunol 170, 3890–3897 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu S, Wang Y, Chen W, Li W, Wang A, Wong S, Bao G, Li J, Yang H, Tracey KJ, D’Angelo J, and Wang H, “High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) Counter-Regulates Serum Amyloid A (SAA)-Induced sPLA2-IIE and sPLA2-V Expression in Macrophages,” PLoS. One 11, e0167468 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li W, Zhu S, Li J, D’Amore J, D’Angelo J, Yang H, Wang P, Tracey KJ, and Wang H, “Serum Amyloid A Stimulates PKR Expression and HMGB1 Release Possibly through TLR4/RAGE Receptors,” Mol. Med 21, 515–525 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen W, Zhu S, Wang Y, Li J, Qiang X, Zhao X, Yang H, D’Angelo J, Becker L, Wang P, Tracey KJ, and Wang H, “Enhanced Macrophage Pannexin 1 Expression and Hemichannel Activation Exacerbates Lethal Experimental Sepsis,” Sci. Rep 9, 160–37232 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, and Ramsay G, “2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference,” Crit Care Med. 31, 1250–1256 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu S, Ashok M, Li J, Li W, Yang H, Wang P, Tracey KJ, Sama AE, and Wang H, “Spermine protects mice against lethal sepsis partly by attenuating surrogate inflammatory markers,” Mol. Med 15, 275–282 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li W, Zhu S, Li J, Assa A, Jundoria A, Xu J, Fan S, Eissa NT, Tracey KJ, Sama AE, and Wang H, “EGCG stimulates autophagy and reduces cytoplasmic HMGB1 levels in endotoxin-stimulated macrophages,” Biochem. Pharmacol 81, 1152–1163 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li W, Zhu S, Li J, Huang Y, Zhou R, Fan X, Yang H, Gong X, Eissa NT, Jahnen-Dechent W, Wang P, Tracey KJ, Sama AE, and Wang H, “A hepatic protein, fetuin-A, occupies a protective role in lethal systemic inflammation.,” PLoS ONE 6, e16945 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.