Abstract

Background:

Vascular injury and inflammation during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is associated with increased risk of post-PCI adverse outcomes. Colchicine decreases neutrophil recruitment to sites of vascular injury. The anti-inflammatory effects of acute colchicine administration prior to PCI on subsequent myocardial injury are unknown.

Methods:

In a prospective, single-site trial, subjects referred for possible PCI (n=714) were randomized to acute pre-procedural oral administration of colchicine 1.8 mg or placebo.

Results:

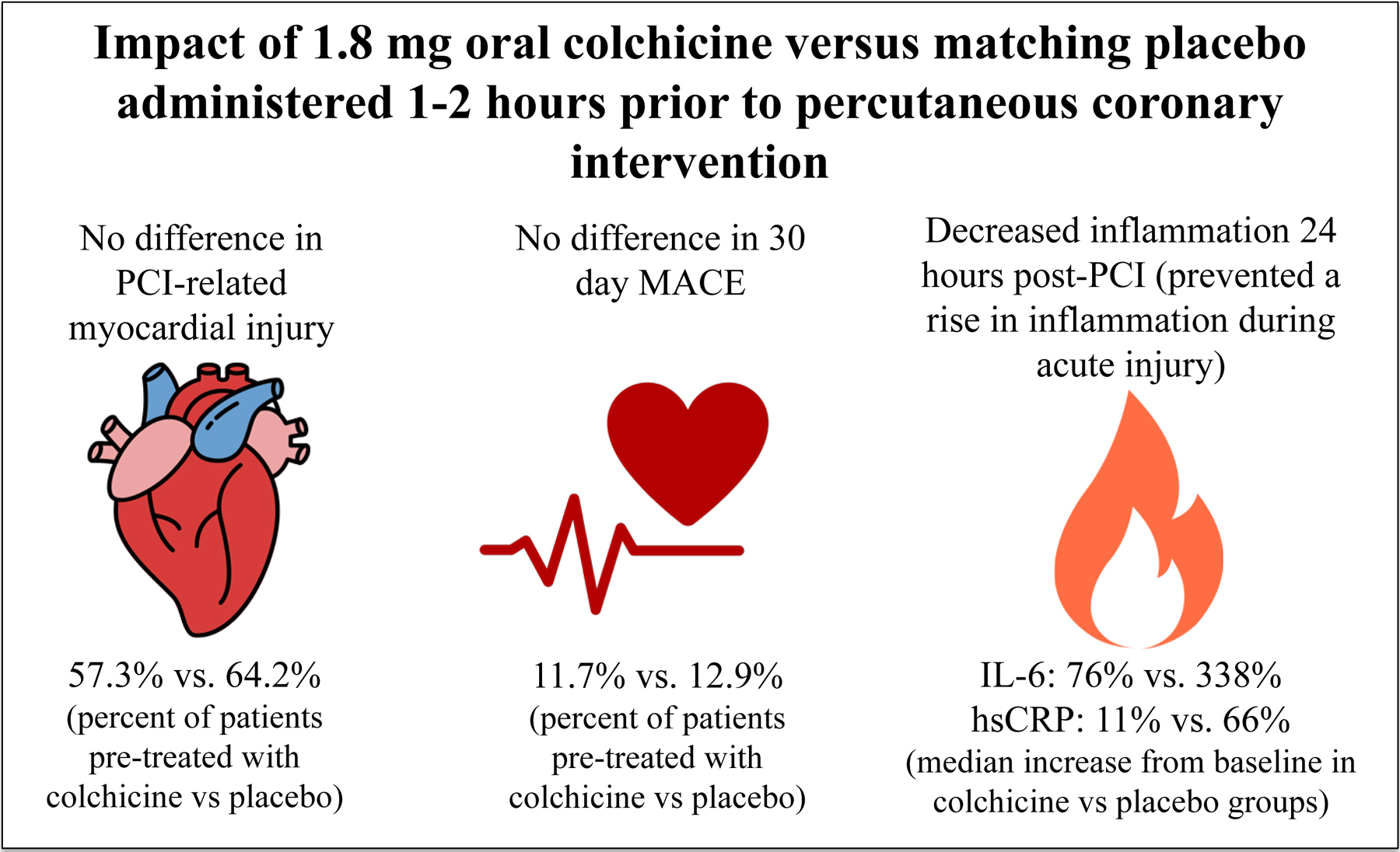

Among the 400 subjects who underwent PCI, the primary outcome of PCI-related myocardial injury did not differ between colchicine (n=206) and placebo (n=194) groups (57.3% vs. 64.2%, p=0.19). The composite outcome of death, non-fatal myocardial infarction and target vessel revascularization at 30 days (11.7% vs. 12.9%, p=0.82) and the outcome of PCI-related myocardial infarction defined by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (2.9% vs. 4.7%, p=0.49) did not differ between colchicine and placebo groups. Among 280 PCI subjects in a nested inflammatory biomarker sub-study, the primary biomarker endpoint, change in interleukin-6 concentrations did not differ between groups one hour post-PCI, but increased less 24 hours post-PCI in the colchicine (n=141) versus placebo group (n=139) (76% [−6, 898] vs. 338% [27, 1264], p=0.02). High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) concentration also increased less after 24 hours in the colchicine versus placebo groups (11% [−14, 80] vs. 66% [1, 172], p=0.001).

Conclusions:

Acute pre-procedural administration of colchicine attenuated the increase in interleukin-6 and hsCRP concentrations after PCI when compared with placebo but did not lower the risk of PCI-related myocardial injury.

Trial Registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov (identifiers: NCT02594111, NCT01709981)

Keywords: colchicine, percutaneous coronary intervention, PCI-related myocardial injury

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Vascular injury during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) induces rapid neutrophil recruitment to the site of mechanical trauma. The subsequent inflammatory cascade can be detected as early as one hour after PCI.1–6 Elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers in the setting of PCI are associated with endothelial dysfunction and microvascular obstruction and remains an independent predictor of subsequent major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) even in the contemporary era of second-generation drug-eluting stents.7–15 Inflammation during PCI may also increase the risk of PCI-related myocardial injury, which is associated with long-term all-cause mortality.16

Colchicine directly inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis and activity in response to vascular injury, indirectly reduces the production of active interleukin (IL)-1β via inhibitory effects on the inflammasome and reduces neutrophil-platelet aggregates, which may accumulate in the microvascular beds during acute myocardial infarction (MI) and contribute to myocardial injury after PCI.17–22 A two-dose regimen of colchicine (1.2 mg followed by 0.6 mg administered over an hour) currently used for the treatment of gout flares has rapid anti-inflammatory effects and an adverse event profile comparable to placebo.23 The aim of this study was to determine if an acute, pre-procedural oral administration of 1.8 mg of colchicine reduces PCI-related myocardial injury.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

The COLCHICINE-PCI study is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine the effects of acute pre-procedural oral administration of 1.8 mg of colchicine on PCI-related myocardial injury. A nested inflammatory biomarker substudy was performed to further delineate changes in inflammatory profiles associated with colchicine administration. The trial was funded by the Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Research and Development and the American Heart Association. This study was approved by the local institutional review boards. All subjects provided written, informed consent. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Subjects

Adults age 18 years or older with suspected ischemic heart disease or acute coronary syndromes referred for clinically indicated coronary angiography with possible PCI were eligible for inclusion. Subjects were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: 1) use of oral steroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents other than aspirin within the longer of 72 hours or three times the agent’s half-life, 2) high-intensity statin treatment started within 24 hours of procedure, 3) glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/minute or on dialysis, 4) use of strong CYP3A4/P-glycoprotein inhibitors, 5) chronic colchicine use or history of intolerance to colchicine, 6) active malignancy or infection, 7) history of myelodysplasia, 8) participation in a competing study, 9) inability to provide informed consent, 10) any condition that, in the investigator’s opinion, may put the subject at significant risk, may confound the study results, or may interfere significantly with the subject’s ability to adhere with study procedures. Recruitment began May 30, 2013 at Bellevue Hospital Center and was transitioned to the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, Manhattan Campus January 29, 2015. Study enrollment completed on August 29, 2019.

Randomization and Study Drug Allocation

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups: 1) oral colchicine 1.2 mg one to two hours before coronary angiography, followed by colchicine 0.6 mg one hour later or immediately pre-procedure if taken to the catheterization laboratory more urgently, or 2) matching placebo at the same time points. A stratified randomization code was generated by an independent statistician using random block sizes and held by the research pharmacies for treatment assignment. Subjects, the investigative team, and the clinical team involved in the patient’s care were blinded to treatment assignment until all subjects completed 30-day follow-up and the study database for the primary analyses was locked. The randomization scheme was stratified according to prior HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor exposure: 1) subjects who received new treatment with high-intensity statin therapy 24 hours to seven days prior to the procedure (i.e., increase in the patient’s maintenance regimen to a high-intensity statin or newly started on a high-intensity statin), or 2) subjects on a stable statin treatment regimen (either no change in dose for at least seven days or not administered a statin). The decision to treat with high-intensity statin therapy prior to PCI was made by the treating physician. The rationale for this stratification was to decrease the potential confounding effects of acute high-intensity statin pre-treatment on PCI-related myocardial injury.24 Colchicine study drug and placebo were supplied by URL Pharma, Inc from the time of study initiation until a change in company ownership on September 30, 2016. Thereafter, study drug and placebo were supplied by the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, Manhattan Campus Research Pharmacy.

Study Protocol

All enrolled subjects underwent assessment of Troponin I (Ultra) assay (Siemens Centaur CP Chemistry Analyzer, Siemens Healthineers, Germany) at pre-treatment baseline. Subjects who underwent PCI had repeat assessment of Troponin I at 6 to 8 hours post-PCI and at 22 to 24 hours post-PCI and a clinical assessment performed at 30 days post-PCI. Subjects who met inclusion and had no exclusion criteria for the main trial were consecutively included in a nested inflammatory biomarker substudy when lab personnel were available to process biospecimens. All subjects in the nested inflammatory biomarker substudy underwent assessment of inflammatory biomarkers at pre-treatment baseline. Subjects in the substudy who subsequently underwent PCI had additional assessments of IL-6 and IL-1β at one hour post-PCI, 6 to 8 hours post-PCI, and 22 to 24 hours post-PCI. For the assessment of IL-6 and IL-1β concentrations, citrate-anticoagulated blood was centrifuged within 30 minutes of collection at 2500g for ten minutes, and plasma aliquots were stored at −80°C until analysis. IL-6 and IL-1β concentrations were assessed using multiplex assays (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) on the MAGPIX multiplex instrument (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX). Additionally, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) concentration was assessed at pre-treatment baseline and 22–24 hours post-PCI with a commercial assay (Siemens ADVIA 1800 Chemistry Analyzer, Siemens Healthineers, Germany). Adverse events were monitored by a Data Safety Monitoring Committee comprised of two cardiologists and a rheumatologist who were also blinded to treatment allocation.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was PCI-related myocardial injury according to the Universal Definition based on Troponin I measurements at 6 to 8 hours and 22 to 24 hours post-PCI.25 In brief, PCI-related myocardial injury was defined as the peak post-procedure Troponin I above the upper reference limit in subjects with normal baseline cardiac biomarkers, or > 20% from the most recent pre-procedural level in subjects with elevated but stable or falling baseline cardiac biomarkers.25

A key secondary outcome was the occurrence of 30-day MACE, a composite of the earliest occurrence of death from any cause, non-fatal MI, or target vessel revascularization. Non-fatal MI was defined as PCI-related (type 4a) or type 1 MI per the Third Universal Definition.25 Another secondary outcome was PCI-related MI as defined by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions.26

The primary endpoint of the nested inflammatory biomarker substudy was the change in plasma IL-6 concentration between baseline and one hour post-PCI. Secondary endpoints of the nested inflammatory biomarker substudy were change in plasma IL-6 concentration between baseline and 6 to 8 hours and between baseline and 22 to 24 hours post-PCI. Other substudy secondary endpoints were change in plasma IL-1β concentration between baseline and one hour, between baseline and 6 to 8 hours, and between baseline and 22 to 24 hours post-PCI and change in hsCRP concentration between baseline and 22 to 24 hours post-PCI.

Statistical Analyses

A total of 400 subjects who undergo PCI was expected to provide 80% power at a two-sided 0.05 significance level to detect a reduction in PCI-related myocardial injury from 30% risk in the placebo arm to 18% risk in the colchicine arm.27 Sample size for the inflammatory biomarker substudy was calculated based on published mean plasma IL-6 concentration of 12 pg/mL and standard deviation of 12 pg/mL one hour after PCI.5 A total of 258 subjects who undergo PCI was expected to provide 78% power at a two-sided 0.05 significance level to detect a difference in means when there is a difference of 0.35 between the null hypothesis mean difference of 0.0 between the colchicine versus placebo groups and the actual mean difference of 0.35 using a two-sided Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test. These results are based on 2000 Monte Carlo samples from the normal distributions of both groups and standard deviation of one. To account for a potential floor effect, in which low baseline inflammatory levels limit the detection of post-PCI changes, the sample size for the nested biomarker substudy was increased to 280 subjects.

An intention-to-treat approach in randomized subjects undergoing PCI was utilized for the primary analytic approach. The entire randomized study cohort with or without PCI was utilized for the safety assessment. Categorical variables are presented as frequency (proportion), normally distributed continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation, and skewed continuous variables as median [interquartile range]. Categorical variables and outcomes were compared between colchicine and placebo groups using chi-square test, or fisher’s exact test if the cell number was less than 5, and continuous variables were compared between colchicine and placebo groups using two sample t-test, or Mann-Whitney test when appropriate. Inflammatory markers were examined in subjects from baseline to post-PCI using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Percent changes in IL-6 and IL-1β concentrations from baseline to one hour, from baseline to 6 to 8 hours, and from baseline to 22 to 24 hours and percent change in hsCRP concentration from baseline to 22 to 24 hours were compared between the colchicine and placebo groups using the Mann-Whitney test. A sensitivity analysis was performed of the repeated inflammatory marker measures over time by treatment group using a linear mixed model analysis. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

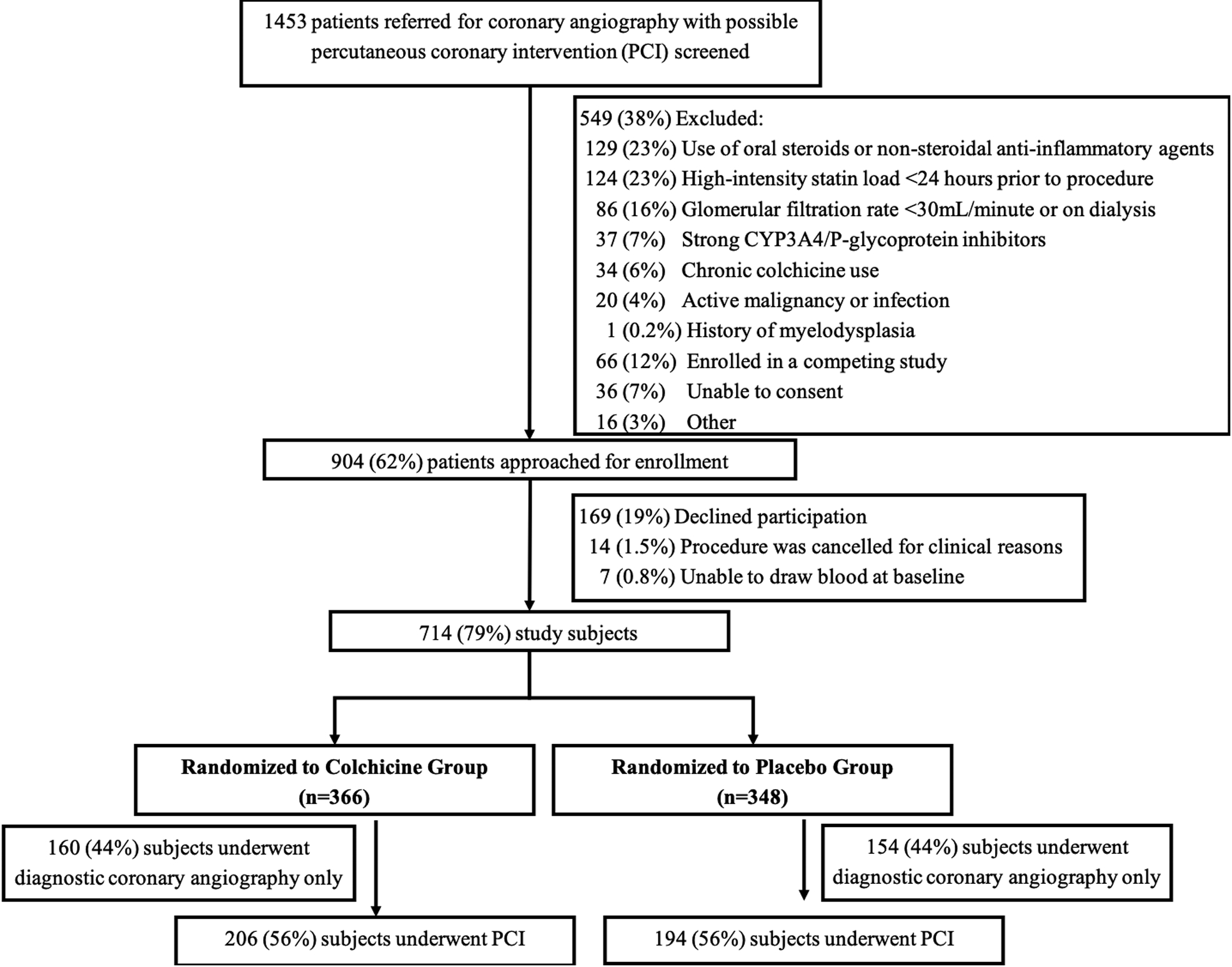

Of the 904 patients eligible to participate in the trial, 714 (79%) were included in the study cohort, 146 from Bellevue Hospital Center and 568 from the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, Manhattan Campus (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the entire study cohort are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Of the 366 subjects randomized to acute pre-procedural oral administration of colchicine 1.8 mg, 206 (56%) underwent PCI, and of the 348 subjects randomized to matching placebo, 194 (56%) underwent PCI (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Screening, enrollment, and randomization of study population

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects who underwent PCI did not differ between the colchicine and placebo groups (Table 1). A majority of the subjects were male, 76% were white, and 21% were of Hispanic ethnicity. Cardiovascular risk factors were common, with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus in 92%, 89%, and 58% of subjects, respectively. Prior MI was reported in 26% of subjects, prior coronary revascularization in more than a third, and renal insufficiency in 21%. A majority of subjects were treated with aspirin and statin therapy prior to the procedure, and approximately two-thirds had been loaded with a P2Y12 inhibitor. Among subjects not prescribed aspirin or a P2Y12 inhibitor at the baseline assessment, an acute loading dose of aspirin 325 mg and/or clopidogrel 600 mg were administered immediately pre-procedure based on clinician discretion. Ninety-one percent of the subjects were on statin therapy pre-procedure, 66% on chronic high-intensity statin therapy, and 21% on a new treatment with high-intensity statin therapy 24 hours to seven days pre-procedure. The proportion of subjects with a pre-procedural hsCRP concentration >2 mg/L was 62%. Severe multivessel coronary artery disease was present in 55% of subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention randomized to an acute pre-procedural oral load of colchicine or placebo

| Colchicine (n=206) |

Placebo (n=194) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.9 ± 9.9 | 66.6 ± 10.2 |

| Male sex, % | 193 (93.7) | 181 (93.3) |

| Race, % | ||

| White | 159 (77.2) | 144 (74.2) |

| Black | 41 (19.9) | 37 (19.1) |

| Asian | 5 (2.4) | 12 (6.2) |

| Other | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % | 42 (20.4) | 43 (22.2) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.9 ± 5.8 | 29.3 ± 5.4 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 98.9 ± 14.3 | 98.1 ± 13.0 |

| Hypertension, % | 192 (93.2) | 175 (90.2) |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 182 (88.3) | 173 (89.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 114 (55.3) | 117 (60.3) |

| Insulin-treated diabetes mellitus, % | 54 (26.3) | 49 (25.3) |

| Prior myocardial infarction, % | 51 (24.8) | 52 (26.8) |

| Prior coronary revascularization, % | 75 (36.4) | 75 (38.7) |

| Congestive heart failure, % | 44 (21.4) | 28 (14.4) |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack, % | 19 (9.2) | 17 (8.8) |

| Carotid artery disease, % | 9 (4.4) | 10 (5.2) |

| Peripheral artery disease, % | 16 (7.8) | 18 (9.3) |

| Renal insufficiency, % | 45 (21.8) | 38 (19.6) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, % | 29 (14.1) | 32 (16.5) |

| Tobacco use, % | 148 (71.8) | 134 (69.1) |

| Current tobacco use, % | 43 (20.9) | 46 (23.7) |

| Aspirin, % | 196 (95.1) | 187 (96.4) |

| P2Y12 inhibitor, % | 126 (61.2) | 118 (60.8) |

| Statin, % | 185 (89.8) | 177 (91.2) |

| High-intensity statin, % | 131 (63.6) | 134 (69.4) |

| New treatment with high-intensity statin therapy 24 hours to seven days pre-procedure, % | 42 (20.4) | 42 (21.6) |

| Beta blocker, % | 180 (87.4) | 159 (82.0) |

| Calcium channel blocker, % | 48 (23.3) | 38 (19.6) |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, % | 130 (63.1) | 132 (68.0) |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 77 [57, 105] | 81 [62, 97] |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 39 [33, 45] | 38 [34, 46] |

| Non HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 109 [81, 140] | 109 [87, 131] |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 6.3 [5.8, 7.7] | 6.4 [5.7, 7.8] |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 113 [97, 145] | 110 [95, 145] |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 78 [62, 95] | 79 [64, 95] |

| White blood cell count, x109/L | 7.2 [6.1, 8.4] | 7.3 [5.9, 8.6] |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | 2.55 [1.79, 3.52] | 2.50 [1.83, 3.77] |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.9 [12.4, 14.7] | 13.8 [12.5, 14.6] |

| Platelet count, x109/L | 211 [183, 251] | 211 [175, 248] |

| High sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | 3.3 [1.1, 9.1] | 3.1 [0.1, 9.0] |

| High sensitivity C-reactive protein >2 mg/L, % | 127 (62.6) | 113 (60.1) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | ||

| Normal or borderline | 145 (72.1) | 132 (69.8) |

| Mildly/moderately reduced | 40 (19.9) | 44 (23.3) |

| Severely reduced | 16 (8.0) | 13 (6.9) |

| Indication for coronary angiography, % | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 103 (50.0) | 95 (49.0) |

| Number of coronary arteries severely diseased, % | ||

| 1 | 91 (44.2) | 91 (46.9) |

| 2 | 76 (36.9) | 56 (28.9) |

| 3 | 39 (18.9) | 47 (24.2) |

| Left main disease, % | 5 (2.4) | 6 (3.1) |

| LAD artery, % | 150 (72.8) | 136 (70.1) |

| Proximal LAD artery disease, % | 61 (29.6) | 46 (23.7) |

| Circumflex artery disease, % | 104 (50.5) | 98 (50.5) |

| Right coronary artery disease, % | 101 (49.0) | 106 (54.6) |

| Multivessel coronary artery disease, % | 115 (55.8) | 103 (53.1) |

HDL=high density lipoprotein, LAD= Left anterior descending artery disease, LDL=low density lipoprotein

Of the 50% (n=198) of subjects with acute coronary syndrome as the indication for coronary angiography, 30% (n=59) presented with unstable angina and 70% (n=139) with MI. Troponin I concentration was abnormal at baseline in 29% (n=117) with no difference between the colchicine and placebo groups (31% vs 27%, p=0.48). A down-trending troponin pattern was observed in 24% (n=95), while 5.5% (n=22) had elevated troponins pattern that had not yet declined from the peak measurement prior to PCI. The troponin pattern at baseline did not differ between the colchicine and placebo groups (p=0.64).

Procedural Characteristics

Procedural characteristics of subjects who underwent PCI are presented in Table 2. PCI was successfully performed in 98% of subjects, and intra-procedural complications occurred in 4.5% of subjects with no differences between the colchicine and placebo groups. Radial arterial access was used for PCI in 88%. A median of one coronary stent was deployed per subject, and only about 10% underwent multi-vessel intervention during the index procedure. The 400 subjects underwent PCI of 500 lesions. Fewer than 10% of treated lesions had TIMI 0/1 flow prior to PCI, and 99% of subjects had TIMI 3 flow post-PCI. Fewer than one in five treated lesions were bifurcation or calcified lesion, and one in five treated lesions were ≥33 mm in length. The majority of treated lesions treated were de novo and not within a prior stent.

Table 2.

Procedural characteristics of subjects undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) randomized to an acute pre-procedural oral load of colchicine or placebo

| Colchicine (n=206) |

Placebo (n=194) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access site, % | 0.96 | ||

| Radial artery | 179 (86.9) | 167 (86.1) | |

| Femoral artery | 24 (11.7) | 24 (12.4) | |

| Radial and femoral arteries | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | |

| Number of stents deployed | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 2] | 0.56 |

| Total stent length, mm | 28 [18, 38] | 28 [18, 38] | 0.79 |

| Number of inflations | 6 [4, 8] | 6 [4, 8] | 0.68 |

| Multivessel intervention, % | 25 (12.1) | 21 (10.8) | 0.80 |

| Lesion level characteristics | (n=258) | (n=242) | |

| Pre-procedural TIMI 0/1 flow, % | 13 (5.0) | 19 (7.9) | 0.95 |

| Stent diameter, mm2 | 3.00 [2.50, 3.00] | 2.75 [2.50, 3.00] | 0.59 |

| Maximum pressure on last device, atm | 20 ± 4 | 20 ± 5 | 0.65 |

| Bifurcation, % | 40 (15.5) | 36 (14.9) | 0.89 |

| Heavily calcified, % | 35 (13.6) | 45 (18.6) | 0.63 |

| Tortuous, % | 17 (6.6) | 25 (10.3) | 0.74 |

| Chronic total occlusion, % | 14 (5.4) | 11 (4.5) | 0.86 |

| Lesion length >33 mm, % | 57 (22.1) | 52 (21.5) | 0.77 |

| Thrombus, % | 12 (4.7) | 9 (3.7) | 0.91 |

| Re-stenosis, % | 16 (6.2) | 11 (4.5) | 0.82 |

| (n=206) | (n=194) | ||

| Post-procedural TIMI 3 flow, % | 202 (98.1%) | 193 (99.5%) | 0.37 |

| Successful PCI, % | 203 (98.5) | 190 (97.9) | 0.94 |

| Intra-procedural complication, % | |||

| Abrupt closure | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0.49 |

| Side branch occlusion | 4 (1.9) | 2 (1.0) | 0.69 |

| Persistent flow reduction | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.5) | 0.36 |

| Distal embolus | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0.49 |

| Major dissection | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | 0.99 |

| Coronary perforation | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0.49 |

| Any complication | 8 (3.9) | 10 (5.2) | 0.71 |

Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and compared using two sample t test. Skewed continuous data are presented as median [interquartile range] and compared using Mann-Whitney test. Categorical data are presented as frequency (proportion) and compared using chi-square test, or fisher’s exact test if the cell number is less than 5. For lesion level characteristics, a linear mixed effect model and a logistic mixed effect model were used to account for the effect of individual subjects on continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Outcomes

Less than 1% of subjects were missing cardiac biomarker data post-PCI and no subjects were lost to follow-up. The primary outcome of PCI-related myocardial injury defined by the Universal Definition did not differ between the colchicine and placebo groups (Table 3). There remained no difference between the colchicine and placebo groups when evaluated by different thresholds of troponin (>1 to 5 upper reference limit: 27.2% vs 29.5%; ≥5 upper reference limit: 30.1% vs 34.7%). Key secondary outcomes of 30-day MACE and PCI-related MI as defined by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (also did not differ between the colchicine and placebo groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) randomized to an acute pre-procedural oral load of colchicine or placebo

| Colchicine (n=206) |

Placebo (n=194) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| PCI-related myocardial injury | 118 (57.3) | 122 (64.2) | 0.19 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| 30-day major adverse cardiovascular events | 24 (11.7) | 25 (12.9) | 0.82 |

| Type 4a myocardial infarction (Universal Definition) | 23 (11.2) | 23 (12.1) | 0.89 |

| Type 1 myocardial infarction (Universal Definition) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0.49 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 0 | 0 | -- |

| All-cause mortality | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.99 |

| PCI-related myocardial infarction (SCAI definition) | 6 (2.9) | 9 (4.7) | 0.49 |

Data are presented as frequency (proportion) and compared using chi-square test, or fisher’s exact test if the cell number is less than 5.

The effect of colchicine versus placebo on PCI-related myocardial injury did not differ in pre-specified subgroups based on acute coronary syndrome indication for PCI, presence of intra-procedural complication, baseline hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L, or new treatment with high-intensity statin therapy 24 hours to seven days pre-procedure (Supplemental Figure 1). All outcomes are presented by acute coronary syndrome presentation status in Supplemental Table 2.

Inflammatory Biomarker Substudy

Characteristics of randomized subjects who underwent PCI and were enrolled in the nested inflammatory biomarker substudy versus those not enrolled in the substudy are presented in Supplemental Table 3. There were no differences in the demographic, clinical, and procedural characteristics between subjects in the nested inflammatory biomarker substudy who underwent PCI and were randomized to colchicine (n=141) versus placebo (n=139) (data not shown).

For all subjects in the substudy, median IL-6 concentration did not significantly increase from baseline (3.71 pg/mL [0.99, 9.60]) to one hour after PCI (4.49 pg/mL [1.21, 11.15], p=0.10), but did increase from baseline to 6 to 8 hours after PCI (8.58 pg/mL [2.71, 18.55], p<0.0001) and from baseline to 22 to 24 hours after PCI (7.48 pg/mL [2.52, 14.20], p<0.0001). Although colchicine did not attenuate the percent increase in IL-6 concentrations at 6 to 8 hours post-PCI, it did attenuate the median percent increase in IL-6 concentrations at 22–24 hours post-PCI when compared to placebo (Figure 2A). Median IL-6 concentrations over time in the colchicine versus placebo groups are shown in Supplemental Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

Percent change in interleukin (IL)-6 concentration (A) and IL-1β concentration (B) from baseline to one hour, baseline to 6 to 8 hours, and baseline to 22 to 24 hours post-PCI in the colchicine versus placebo groups; and percent change in high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) concentration (C) from baseline to 22 to 24 hours post-PCI in the colchicine versus placebo groups.

Data are shown as median [interquartile range] of the percent changes, and percent changes in inflammatory marker concentrations from baseline to one hour, from baseline to 6 to 8 hours, and from baseline to 22 to 24 hours were compared between the colchicine and placebo groups using Mann-Whitney test.

For all subjects in the substudy, median IL-1β concentration did not significantly increase from baseline (0.63 pg/mL [0.38, 1.26]) to one hour post-PCI (0.63 pg/mL [0.33, 1.26], p=0.68), to 6 to 8 hours post-PCI (0.67 pg/mL [0.31, 1.26], p=0.85), and to 22 to 24 hours post-PCI (0.63 pg/mL [0.29, 1.26]), p=0.46). There were no differences in the median percent change in IL-1β concentration from baseline to post-PCI between the colchicine and placebo groups (Figure 2B). Median IL-β concentrations over time in the colchicine versus placebo groups are shown in Supplemental Figure 2B.

For all subjects in the substudy, hsCRP concentration increased from baseline (3.0 mg/L [0.9, 9.2]) to 22 to 24 hours post-PCI (4.9 mg/L [1.7, 11.9], p<0.0001). Colchicine attenuated the median percent increase in hsCRP concentration from baseline to 22–24 hours post-PCI when compared to placebo (Figure 2C). Median hsCRP concentrations over time in the colchicine versus placebo groups are shown in Supplemental Figure 2C.

Subjects in the substudy were further evaluated by the presence (n=74) or absence (n=206) of an abnormal Troponin at baseline as shown in Supplemental Figure 3.

Adverse Events

Peri-procedural adverse events from baseline assessment through hospital discharge in the entire study cohort are shown in Table 4. The most common adverse events were chest pain (8.1%), which did not differ between groups, and gastrointestinal symptoms (6.3%), which occurred more frequently in the colchicine (9.3%) versus placebo (3.2%) group. Other adverse events occurred at a low frequency. Although five serious adverse events occurred in the colchicine group (compared with 12 in the placebo group), only one was deemed by the Data Safety Monitoring Committee to be possibly or probably due to study participation. This event was abdominal discomfort post-procedure that resulted in additional testing with an abdominal ultrasound and prolongation of hospital stay by one day.

Table 4.

Adverse events

| Colchicine (n=366) |

Placebo (n=348) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chest pain, % | 33 (9.0) | 25 (7.2) | 0.45 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms, % | 34 (9.3) | 11 (3.2) | 0.001 |

| Hypersensitivity reaction, % | 4 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) | 0.99 |

| Access site discomfort, % | 4 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) | 0.99 |

| Hemodynamic instability, % | 0 | 5 (1.4) | 0.03 |

| Fever, % | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0.24 |

| Elevated creatinine, % | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0.62 |

| Ischemic stroke, % | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0.99 |

| Fluid overload, % | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.99 |

| Urinary retention, % | 2 (0.5) | 0 | 0.50 |

| Bleeding, % | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0.62 |

| Palpitations, % | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0.49 |

| Headache, % | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0.99 |

| Serious adverse events total, % | 5 (1.4) | 12 (3.4) | 0.11 |

Categorical data are presented as frequency (proportion) and compared using chi-square test, or fisher’s exact test if the cell number is less than 5.

Discussion

This single-site prospective randomized double-blind study is the first to evaluate the effects of an acute pre-procedural administration of colchicine versus placebo on markers of myocardial injury and inflammation in patients undergoing PCI. The most salient findings are that pre-procedural administration of 1.8 mg colchicine did not lower the risk of PCI-related myocardial injury, PCI-related MI, or MACE at 30 days when compared with placebo, but did significantly attenuate the increase in IL-6 and hsCRP concentrations 22–24 hours post-PCI when compared to placebo. Finally, PCI was not associated with increase in IL-1β in either treatment group, suggesting that IL-1β is not an appropriate marker for vascular injury and inflammation in this setting.

PCI-related myocardial injury may be partly due to wire injury, microdissections at the site of balloon inflations, and vascular trauma due to high-pressure balloon inflations. Leukocytes are rapidly recruited to sites of endothelial injury with subsequent increases in IL-6 concentrations.2–3,5–6 PCI-related myocardial injury may also result from mechanical events, such as distal microemboli and side branch occlusion from plaque shift. A pro-inflammatory state during PCI may lead to endothelial dysfunction and leukocyte-platelet aggregates in distal beds, which, in turn, can limit the ability of the coronary microvasculature to accommodate atherothrombotic debris.28–31 Despite the use of contemporary techniques, devices, and pharmacology, systemic inflammation at the time of PCI is associated with adverse events, including cardiac death, stent thrombosis and target lesion revascularization, as early as 30 days post-PCI.7,9,15

Colchicine, an anti-inflammatory agent traditionally used to treat gout, suppresses neutrophil homotypic adhesion, modulates neutrophil deformability, decreases neutrophil extravasation and suppresses an enzymatic component of the inflammasome, leading to reductions in IL-1β and IL-6.18–19 Colchicine has also been shown to decrease levels of neutrophil-platelet aggregates, and incrementally decrease hsCRP concentrations on a background of aspirin and statin therapy.32 The lack of benefit of colchicine on PCI-related myocardial injury in the current study may be attributable to the pharmacodynamics of colchicine—including too short of a time period for colchicine administration pre-PCI and/or an insufficiently potent dosage, particularly in the setting of acute coronary syndrome and mechanical intra-procedural complications, plaque shift, distal emboli. The 1.8 mg dose of colchicine used in the current trial was chosen based on pharmacodynamic data demonstrating maximum plasma concentration within one to two hours of administration and safety and efficacy data in acute gout flares.23 However, these efficacy data are confounded by the daily administration of colchicine thereafter, which was not done in our trial. Alternatively, the presence of redundant pathways of vascular injury and inflammation in a high-risk cohort with multiple vascular risk factors may play a role in negating any possible colchicine effect.

Anti-inflammatory therapy remains a promising therapeutic option to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients undergoing PCI. Acute pre-procedural administration of high-intensity statin therapy has been shown to reduce PCI-related myocardial injury and MI prior to elective PCI and in patients undergoing PCI for acute coronary syndrome, though the supportive studies are few, leaving some debate on their effects on the extent of PCI-related myocardial injury.27,33,34 Decreases in PCI-related myocardial injury associated with acute high-intensity statin pre-treatment parallel attenuations in post-PCI elevation of inflammatory cellular adhesion molecules.35–36 However, since statins exert their actions via post-translational modification of small G proteins, they were administered at least 12 hours in advance of PCI in prior trials. Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS) demonstrated the anti-IL-β antibody, canakinumab, to reduce MACE in the setting of lowering IL-6 and hsCRP concentrations in patients with prior MI but is not available for a cardiovascular indication due to its side effect profile.37 Therefore, there remains a need for a well-tolerated, oral, rapid acting anti-inflammatory agent, especially in the settings of urgent PCI and patients who are referred for PCI but have not received statin therapy prior to the procedure.38–39

The observed primary event rate in the current trial was higher than expected at 64% in the placebo arm, when compared with reported rates in the Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty (ARMYDA) (stable angina) and ARMYDA-Recapture (stable angina and non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome) trials.32,24 The higher event rate in our trial might be attributable to higher rates of diabetes mellitus, severe multivessel coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes in our study cohort. While the primary event rate of PCI-related myocardial injury was more easily captured in the subgroup that did not present with acute coronary syndrome, the rate of 30-day MACE, driven predominately by type 4A MI defined by the Universal Definition, was higher in the subgroup that presented with acute coronary syndrome.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that colchicine can prevent an acute rise of inflammatory biomarkers in an acute setting. Our observations that colchicine suppressed post-PCI increases in IL-6 and hsCRP concentrations without inhibiting myocardial damage suggest that increases in these markers may be secondary, rather than contributory to myocardial injury, or any effect of colchicine via these markers may require a longer time frame to appreciate. Although one report randomized 40 acute coronary syndromes patients to an acute colchicine loading dose versus no colchicine prior to cardiac catheterization and demonstrated a lower concentration of coronary sinus concentrations of both IL-6 and IL-1β with colchicine, they did not have baseline concentrations to compare to and the single time-point measurements were taken pre-PCI.40 In the current trial, colchicine attenuated the increase in both IL-6 and hsCRP concentrations at 22 to 24 post-PCI, but did not affect the increase in these markers observed at 6 to 8 hours post-PCI, and, therefore, it is possible that earlier pre-procedural administration of colchicine may have a benefit. Prior reports have also demonstrated a difference in the concentration and rise in concentrations of inflammatory markers by sampling source.5,40 However, another report of 25 patients predominantly with acute coronary syndromes demonstrated only a 1.5-fold increase in median IL-6 concentration from baseline to one hour post-PCI, while at 24 hours post-PCI, there was a 3.2-fold increase in median IL-6 concentration, paralleling the trend in relative change in median IL-6 concentrations post-PCI in the current trial.6

Limitations

The current findings are supported by several strengths of the study design and execution, including the double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study design and high adherence to study procedures. There are several caveats that limit interpretation of the findings. First, the high proportion of multiple cardiac risk factors of the study population due to referral bias at an academic medical center limits generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the majority male population enrolled within the VA system limits interpretation for women undergoing PCI. Second, our observations are limited to the selected acute pre-procedural dosing regimen and the short-term timepoints for biomarkers of myocardial injury and inflammation in study participants with heterogenous presentations for PCI. Prior clinical studies of colchicine in the stable coronary artery disease population evaluated at least 30 days of colchicine at 0.5 mg daily and prior studies in other clinical settings have shown colchicine’s anti-inflammatory effects to continue to increase over days.31,41,42 The large, randomized, multicenter COLCOT (NCT02551094) and CLEAR SYNERGY OASIS 9 (NCT03048825) trials will provide insight into the effects of low-dose daily colchicine within 3 months of MI and twice daily dose of colchicine within 48 hours of ST-segment elevation MI, respectively, on long-term MACE. Third, the primary outcome of the current trial was limited to short-term follow-up at 24 hours. Elevated post-PCI inflammatory biomarkers are associated with an increased rate of restenosis, and one prior study demonstrated a reduction in restenosis with colchicine at six months follow-up.1,10,11,13,43 Finally, genetic data were not collected in the current trial. Resistance to colchicine has been described in 5 to 18% of the familial Mediterranean fever population due to polymorphisms of codon 3435 in the multiple drug resistance gene that encodes the P-glycoprotein membrane effux pump.43–45

In conclusion, short-term pre-procedure colchicine administration attenuated the increase in IL-6 and hsCRP concentration after PCI but did not reduce PCI-related myocardial injury or MACE when compared with placebo.

Supplementary Material

What is Known

Percutaneous coronary intervention can cause vascular inflammation and myocardial injury.

Reducing inflammation after acute myocardial infarction improves outcomes, but there are no currently available drugs to rapidly reduce vascular inflammation.

Colchicine is a potent anti-inflammatory agent that decreases the attachment of inflammatory cells to injured or inflamed vascular endothelium and platelets and also has an excellent side-effect profile.

What the Study Adds

COLCHICINE-PCI is the first trial to demonstrate that a 1.8 mg colchicine given 1–2 hours pre-procedure does not reduce PCI-related myocardial injury or 30-day major cardiovascular events, but does reduce blood markers of vascular inflammation at 24 hours post-procedure when compared to matching placebo.

This is the first study to show that colchicine can prevent a rise in blood markers of vascular inflammation during an acute injury.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this manuscript to the memory of Steven Sedlis, MD, Professor of Medicine, consummate mentor, and dedicated physician who devoted his career to improving patient outcomes, educating the next generation of physicians, and advancing science. Dr. Sedlis played a pivotal role with his contributions to both the design and conduct of this trial.

We acknowledge the contributions of Bhisham Harchandani, MD, Francisco Ujueta, MD, Leandro Maranan, MD, Fatmira Curovic, Angela Lee, Emmanuel Budis, and Jan Osea in data collection for this manuscript. We also acknowledge the contributions of Robert Donnino, MD, Alana Choy Shan, MD, and Michael Toprover, MD in the monitoring of adverse events for this trial.

Funding Sources

The study was partially funded by the American Heart Association Clinical Research Program (13CRP14520000) and the VA Office of Research and Development (iK2CX001074). Data analysis and statistical support was provided by New York University School of Medicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Group. Drug was initially supplied by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and then by the VA New York Harbor Healthcare System, Manhattan Campus Research Pharmacy. The NYU Langone Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center support grant (P30CA016087) partially funds the NYU Langone Precision Immunology Laboratory where the Luminex MAGPIX multiplex instrument was used to measure plasma inflammatory markers.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- hsCRP

high sensitivity C-reactive protein

- IL

interleukin

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular events

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- VA

Veterans Affairs

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Shah serves on the advisory board for Philips Volcano and Radux Devices and serves as a consultant for Terumo Medical. Dr. Pillinger serves as a consultant for Horizon, Sobi and Ampel Biosciences, and is the recipient of investigator-initiated grant support from Hikma and Horizon. Dr. Cronstein has research grant funding from Astra Zeneca and Arcus and is a founder of Regenosine, Inc. Dr. Feit is a shareholder of Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Johnson and Johnson. Dr. Zhong, Dr. Lorin, Dr. Smilowitz, Ms. Xia, Ms. Ratnapala, and Dr. Keller report no relationships with industry. Dr. Katz has research grant funding from Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Amgen, Luitpold, AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Eidos Therapeutics, and Array BioPharma and serves as a consultant for Merck.

References

- 1.Inoue T, Sakai Y, Morooka S, Hayashi T, Takayanagi K, Takabatake Y. Expression of polymorphonuclear leukocyte adhesion molecules and its clinical significance in patients treated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welt FG, Edelman ER, Simon DI, Rogers C. Neutrophil, not macrophage, infiltration precedes neointimal thickening in balloon-injured arteries. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers C, Welt FG, Karnovsky MJ, Edelman ER. Monocyte recruitment and neointimal hyperplasia in rabbits. Coupled inhibitory effects of heparin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:1312–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shu J, Ren N, Du JB, Zhang M, Cong HL, Huang TG. Increased levels of interleukin −6 and MMP-9 are of cardiac origin in acute coronary syndrome. Scan Cardiovasc J. 2007;41:149–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson L, Grip L, Mattsson Hulten L, Hulthe J, Wiklund O. Release of protein as well as activity of MMP-9 from unstable atherosclerotic plaques during percutaneous coronary intervention. J Intern Med. 2007;262:659–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal A, Schneider DJ, Terrien EF, Gilbert KE, Dauerman HL. Increase in interleukin-6 in the first hour after coronary stenting: an early marker of the inflammatory response. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2003;15:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sardella G, Accapezzao D, Di Roma A, Iacoboni C, Francavilla V, Benedetti G, Musto C, Fedele F, Bruno G, Paroli M. Integrin β2-chain (CD18) over-expression on CD4+ T cells and monocytes after ischemia/reperfusion in patients undergoing primary percutaneous revascularization. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2004;17:165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munk PS, Breland UM, Aukrust P, Skadberg O, Ueland T, Larsen AI. Inflammatory response to percutaneous coronary intervention in stable coronary artery disease. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;31:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buffon A, Liuzzo G, Biascucci LM, Pasqualetti P, Ramazzotti V, Rebuzzi AG, Crea F, Maseri A. Preprocedural serum levels of CRP predict early complications and late restenosis after coronary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1512–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter DH, Fichtlscherer S, Sellwig M, Auch-Schwelk W, Schächinger V, Zeiher AM. Preprocedural CRP and cardiovascular events after coronary stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:839–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwaijtaal M, van Diest R, Bar FW, van der Ven AJ, Bruggeman CA, de Baets MH, Appels A. Inflammatory markers predict late cardiac events in patients who are exhausted after PCI. Atherosclerosis. 2005;182:341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patti G, Di Sciascio G, D’Ambrosio A, Dicuonzo G, Abbate A, Dobrina A. Prognostic value of IL-1 receptor antagonist in patients undergoing PCI. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:372–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotooka N, Inoue T, Fujimatsu D, Morooka T, Hashimoto S, Hikichi Y, Uchida T, Sugiyama A, Node K. Pentraxin 3 is a novel marker for stent-induced inflammation and neointimal thickening. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:368–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue T, Uchida T, Sakuma M, Imoto Y, Ozeki Y, Ozaki Y, Hikichi Y, Node K. Cilostazol inhibits leukocyte integrin Mac-1, leading to a potential reduction in restenosis after coronary stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1408–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah B, Baber U, Pocock SJ, Krucoff MW, Ariti C, Gibson CM, Steg PG, Weisz G, Witzenbichler B, Henry TD, et al. White blood cell count and major adverse cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention in the contemporary era: insights from the PARIS study. Circulation: Cardiovasc Interven. 2017;10: e004981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novack V, Pencina M, Cohen DJ, Kleiman NS, Yen CH, Saucedo JF, Berger PB, Cutlip DE. Troponin criteria for myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:502–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terkeltaub RA. Colchicine update: 2008. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;38:411–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paschke S, Weidner AF, Paust T, Marti O, Beil M, Ben-Chetrit E. Technical advance: Inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis by colchicine is modulated through viscoelastic properties of subcellular compartments. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:1091–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudolph SA, Greengard P, Malawista SE. Effects of colchicine on cyclic AMP levels in human leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:3404–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cronstein BN, Molad Y, Reibman J, Balakhane E, Levin RI, Weissmann G. Colchicine alters the quantitative and qualitative display of selectins on endothelial cells and neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:994–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah B, Allen N, Harchandani B, Pillinger M, Katz S, Sedlis SP, Echagarruga C, Samuels SK, Morina P, Singh P, et al. Effect of colchicine on platelet-platelet and platelet-leukocyte interactions: a pilot study in healthy subjects. Inflammation. 2016;39:182–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, Kook KA, Crockett RS, Davis MW. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1060–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Sciascio G, Patti G, Pasceri V, Gaspardone A, Colonna G, Montinaro A. Efficacy of atorvastatin reload in patients on chronic statin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the ARMYDA-RECAPTURE (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty) Randomized Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:558–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:2020–35.22923432 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moussa ID, Klein LW, Shah B, Mehran R, Mack MJ, Brilakis ES, Reilly JP, Zoghbi G, Holper E, Stone GW. Consideration of a new definition of clinically relevant MI after coronary revascularization an expert consensus document from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions (SCAI). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1563–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briguori C, Visconti G, Focaccio A, Golia B, Chieffo A, Castelli A, Mussardo M, Montorfano M, Ricciardelli B, Colombo A. Impact of a single high loading dose of atorvastatin on periprocedural MI: Results from the NAPLES II trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsubara T, Ishibashi T, Hori T, Ozaki K, Mezaki T, Tsuchida K, Nasuno A, Kubota K, Tanaka T, Miida T, et al. Association between coronary endothelial dysfunction and local inflammation of atherosclerotic coronary arteries. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;249:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta SK, Johnson RM, Mather KJ, Clauss M, Rehman J, Saha C, Desta Z, Dubé MP. Anti-inflammatory treatment with pentoxifylline improves HIV-related endothelial dysfunction: a pilot study. AIDS. 2010;24:1377–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gotz AK, Zahler S, Stumpf P, Welsch U, Becker BF. Intracoronary formation and retention of micro aggregates of leukocytes and platelets contribute to postischemic myocardial dysfunction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2005;100:413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren F, Mu N, Zhang X, Tan J, Li L, Zhang C, Dong M. Increased platelet-leukocyte aggregates are associated with myocardial no-reflow in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nidorf M, Thompson PL. Effect of colchicine (0.5mg twice daily) on high-sensitivity CRP independent of aspirin and atorvastatin in patients with stable CAD. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:805–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasceri V, Patti G, Nusca A, Pristipino C, Richichi G, Di Sciascio G; ARMYDA Investigators. Randomized trial of atorvastatin for reduction of myocardial damage during coronary intervention: Results from the ARMYDA study. Circulation. 2004;110:674–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patti G, Pasceri V, Colonna G, Miglionico M, Fischetti D, Sardella G, Montinaro A, Di Sciascio G. Atorvastatin pretreatment improves outcomes in patients with ACS undergoing early PCI: results of the ARMYDA-ACS randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1272–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patti G, Chello M, Pasceri V, Colonna D, Nusca A, Miglionico M, D’Ambrosio A, Covino E, Di Sciascio G. Protection from procedural myocardial injury by atorvastatin is associated with lower levels of adhesion molecules after PCI: Results from the ARMYDA-CAMs substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1560–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patti G, Chello M, Gatto L, Alfano G, Miglionico M, Covino E, Di Sciascio G. Short-term atorvastatin preload reduces levels of adhesion molecules in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Results from the ARMYDA-ACS CAMs (Atorvastatin for Reduction of MYocardial Damage during Angioplasty-Cell Adhesion Molecules) substudy. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2010;11:795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, Fonseca F, Nicolau J, Koenig W, Anker SD, et al. ; CANTOS Trial Group. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borden WB, Redberg RF, Mushlin AI, Dai D, Kaltenbach LA, Spertus JA. Patterns and intensity of medical therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2011;305:1882–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silva MA, Swanson AC, Gandhi PJ, Tataronis GR. Statin-related adverse events: a meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2006;28:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez GJ, Robertson S, Barraclough J, Xia Q, Mallat Z, Bursill C, Celermajer DS, Patel S. Colchicine acutely suppresses local cardiac production of inflammatory cytokines with an acute coronary syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nidorf SM, Eikelboom JW, Budgeon CA, Thompson PL. Low-dose colchicine for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:404–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crittenden DB, Lehmann RA, Schneck L, Keenan RT, Shah B, Greenberg JD, Cronstein BN, Sedlis SP, Pillinger MH. Colchicine use is associated with decreased prevalence of MI in patients with gout. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1458–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deftereos S, Giannopoulos G, Raisakis K, Kossyvakis C, Kaoukis A, Panagopoulou V, Driva M, Hahalis G, Pyrgakis V, Alexopoulos D, et al. Colchicine Treatment for the Prevention of Bare-Metal Stent Restenosis in Diabetic Patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1679–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozer I, Mete T, Sezer OT, Kolbasi Ozgen G, Kucuk GO, Kaya C, Kilic Kan E, Duman G, Ozturk Kurt HP. Association between colchicine resistance and vitamin D in familial Mediterranean fever. Ren Fail. 2015;37:1122–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tufan A, Babaoglu MO, Akdogan A, Yasar U, Calguneri M, Kalyoncu U, Karadag O, Hayran M, Ertenli AI, Bozkurt A, et al. Association of drug transporter gene ABCB1 (MDR1) 3435C to T polymorphism with colchicine response in familial Mediterranean fever. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1540–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.