Abstract

Background:

Many patients are reluctant to speak up about breakdowns in care, resulting in missed opportunities to respond to individual patients and improve the system. Effective approaches to encouraging patients to speak up and responding when they do are needed.

Objective:

To identify factors which influence speaking up, and to examine the impact of apology when problems occur.

Design:

Randomized experiment using a vignette-based questionnaire describing 3 care breakdowns (slow response to call bell, rude aide, unanswered questions). The role of the person inquiring about concerns (MD, RN, patient care specialist), extent of the prompt (invitation to patient to share concerns), and level of apology were varied.

Setting:

National online survey.

Participants:

1,188 adults aged ≥ 35 years were sampled from an online panel representative of the entire US population, created and maintained by GfK, an international survey research organization; 65.5% response rate.

Main Outcomes and Measures:

Affective responses to care breakdowns, intent to speak up, willingness to recommend the hospital.

Results:

Twice as many participants receiving an in-depth prompt about care breakdowns would (probably/definitely) recommend the hospital compared to those receiving no prompt (18.4% versus 8.8% respectively [p=0.0067]). Almost three times as many participants receiving a full apology would (probably/definitely) recommend the hospital compared to those receiving no apology (34.1% versus 13.6% respectively [(p<0.0001]). Feeling upset was a strong determinant of greater intent to speak up, but a substantial number of upset participants would not “definitely” speak up. A more extensive prompt did not result in greater likelihood of speaking up. The inquirer’s role influenced speaking up for two of the three breakdowns (rudeness and slow response).

Conclusions:

Asking about possible care breakdowns in detail, and offering a full apology when breakdowns are reported substantially increases patients’ willingness to recommend the hospital.

INTRODUCTION

As the “closest observers of care”, patients and family members have unique insights into how care is delivered.[1] A growing body of research documents that when asked about their care experiences, patients and family members identify a variety of problematic events.[2–10] Breakdowns in care, which we consider to be anything that has gone wrong in care from the perspective of the patient, encompass medical errors and adverse events identified by the patient, as well as other events – such as communication problems- that would not typically be classified as a medical error. Breakdowns in care are distressingly common, with as many as 40 percent of hospitalized patients perceiving a breakdown in their care.[2,3] Examples of patient-perceived care breakdowns include delayed diagnosis, inadequate information exchange, rude or dismissive manner, medication errors, and problems with procedures.[2] Almost all patient-perceived breakdowns cause emotional distress to patients and family members, and many result in loss of trust, avoidance of medical care, and life disruption.[2,3,9]

Unfortunately, many patients who experience a care breakdown do not speak up.[3,9] Reasons for not speaking up include concerns that doing so will result in worse care, fear of damaging the relationship with the care team, uncertainty about how to report, and the belief that speaking up will be fruitless.[9,11–13] This silence is problematic because providers who are unaware of a patient’s concerns are unable to address the problem or remediate the patient’s concern. In addition, information on the prevalence and impact of patient-perceived care breakdowns could help healthcare organizations identify patient-centered priorities for improvement efforts.[14]

The We Want to Know program is an example of an intensive effort to encourage patients to speak up when they have concerns about their care.[2] The development and implementation of this program uncovered a need for a stronger evidence base on the most effective strategies for eliciting patient concerns. Specifically, hospital stakeholders frequently noted that patients seemed more willing to speak up about breakdowns in care to a neutral entity (the We Want to Know patient care specialist) than to members of the care team or hospital administrators. This observation is consistent with research demonstrating some patients don’t speak up because they’re concerned it will disrupt their relationship with providers[11–13] and led us to question whether who inquires about breakdowns in care influences patient willingness to speak up. Whether the exact phrasing of how one inquires about breakdowns in care influences speaking up is unknown. Finally, this experience also suggested that providers and organizations may be reluctant to inquire about patients’ concerns due to uncertainty about how to respond effectively if a patient does identify a breakdown in care. The beneficial effects of apology following a medical error[15–17] suggest this may be an effective element in responding to patients who speak up about less severe breakdowns in care, but this has not been evaluated.

Our overall goal was to address these questions and provide evidence that can be used to design programs to elicit patient reports of breakdowns in care and effectively respond to patients who speak up about breakdowns. We conducted a national survey using a randomized experiment to examine the impact of two modifiable factors (the role of the person inquiring about the patient’s experience and the wording of the inquiry) on intent to speak up about three common breakdowns in care and on intent to recommend the hospital. We also examined the extent to which participants would be upset about each breakdown, and whether feeling upset was related to intent to speak up. Finally, we investigated the influence of apology on intent to recommend the hospital.

METHODS

Design

The study involved a factorial survey with 9 conditions related to inquiring about care (3 speakers with different roles relative to the patient and 3 variations in the wording of the prompt) followed by 3 levels of apology, creating a total of 27 versions of the questionnaire. Versions were randomly assigned to participants.

Participants and Survey Administration

Participants were sampled from the KnowledgePanel®, an online panel representative of the entire US population, created and maintained by GfK (formerly KnowledgeNetworks), an international survey research organization. Panel members are recruited using probability-based sampling methods and are provided with internet access and hardware if needed. Upon joining the panel, members provide demographic information (e.g., age, education level, household income). GfK offers a modest incentive program to encourage survey participation.

Two rounds of preliminary testing with a convenience sample (not GfK panel members) were conducted by the investigators to assess questionnaire understandability and flow, and to elicit feedback and general recommendations.

GfK administered the online survey to a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized US adults aged 35 and older. Selected members were sent an email notification with a link to the questionnaire; reminders were sent to non-responders 3 and 11 days after the initial notification. GfK administered the questionnaire to a sample of 25 eligible adults as a pilot test prior to fielding the final survey, which was fielded between 6/28/2017 and 7/11/2017.

Survey Instrument

The vignette-based questionnaire contained multiple sections, as summarized in Figure 1; the full text of the questionnaire is provided in Appendix A. The introduction (Section I) encouraged the reader to imagine him/herself hospitalized with undiagnosed abdominal pain. The vignette went on to describe three breakdowns in care: 1) the aide had been slow to respond to the call bell; 2) the aide was rude when she did respond; and 3) the doctor has not been available to answer questions. These events were selected by K.F. and K.M. as exemplars of the types of events reported by hospitalized patients and family members in interviews about their care experiences2 and to represent breakdowns across a range of care domains and providers involved. The vignette description indicated that other aspects of care had been going well (i.e., pain was currently controlled and most of the nurses and aides had been caring and helpful). The introduction (Section I) was the same for all participants.

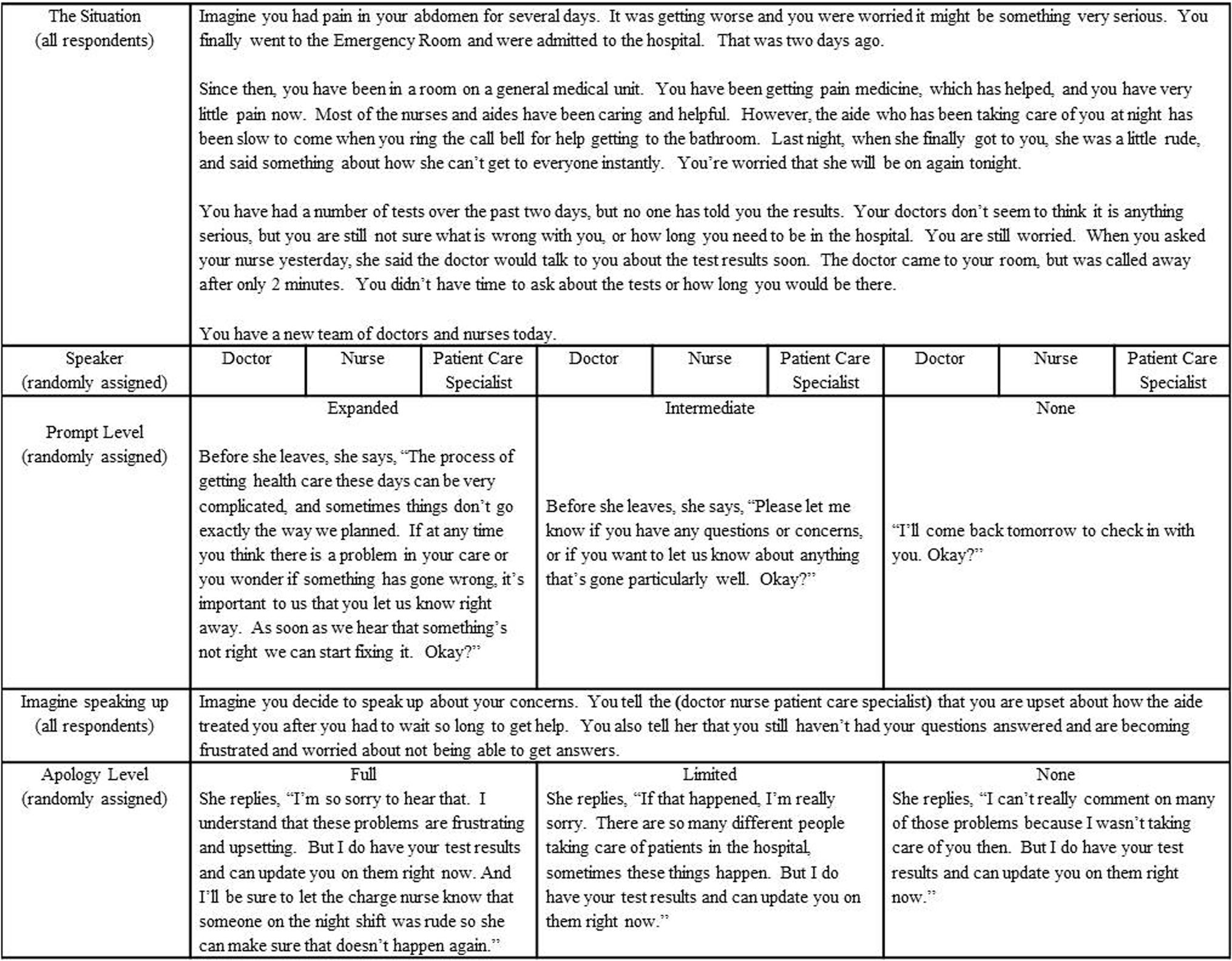

Figure 1.

Summary of Vignette-based Questionnaire

Section II varied 2 factors, each with 3 levels, resulting in 9 conditions which were randomly assigned to participants. Each participant received only one scenario. The text described a doctor, a nurse, or a patient care specialist entering the room, and providing an opportunity for the patient to mention the care breakdowns. Three approaches to asking about care were portrayed; we refer to these as an expanded, intermediate or no prompt about care (exact wording is in Appendix A). In the expanded version, the speaker notes the complexity of healthcare, acknowledges that sometimes things don’t go as planned, and explicitly encourages the patient to speak up right away if anything has gone wrong so that corrective action can be taken. In the intermediate condition the speaker asks the patient to let her know if there are questions or concerns, or if anything has gone particularly well. In the no prompt condition, she simply states that she will check in with the patient the next day.

Section III assessed participants’ reactions to the situation as described to that point. The first three questions in the series asked whether the participant would speak up about each breakdown in care; the next three asked how upset the participant would be about each breakdown in care; one question asked whether the participant would recommend the hospital and one question asked whether the participant felt the doctors, nurses and staff in the hypothetical vignette would want to know if patients have any problems. The latter was included as a manipulation check.

Section IV of the questionnaire instructed participants to imagine they had spoken up about the three breakdowns in care. This instruction was the same for all participants. In Section V participants were randomized to receive one of three levels of apology (full, limited or none) in response to their mentioning their concern. In the full apology condition the speaker expresses regret, empathy, offers to remediate the immediate concern (address unanswered questions) and commits to steps to preventing a recurrence of the breakdown involving the rude aide. In the limited apology condition the speaker makes a conditional statement of regret and offers to remediate the immediate concern. In the no apology condition the speaker offers to remediate the immediate concern only. To make the scenario more realistic, we did not include an acknowledgement of responsibility in the full apology condition, even though this is an element of a full apology. In the hospital setting, the individual who learns about a breakdown and therefore has the opportunity to apologize may not be the same person responsible for the breakdown, making it less realistic for them to acknowledge responsibility. Appendix B shows the correspondence between the dialog for each condition and the elements of apology.

In Section VI participants again indicated whether they would recommend the hospital.

Participants were also asked about recent experience with hospitalization and to rate their health. Demographic data on participants was provided by GfK, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status and employment status.

Analyses

The effectiveness of the randomization was assessed using chi-square statistics to compare groups. We examined the impact of type of breakdown (slow response, rude aide, and unanswered questions) on the participant’s report of intent to speak up and feeling upset using mixed effects modeling to account for within-participant correlation. To assess whether the two potentially modifiable variables (i.e., speaker role and level of prompt) affected intent to speak up, intent to recommend and feeling upset, the relationship between intent to speak up and feeling upset we computed chi-square statistics. We also used chi-square statistics to examine the relationship between level of apology and intent to recommend. To examine possible interactions between different factors, we estimated multinomial logistic regression models for intent to speak up and intent to recommend the hospital, with main effects and interactions between prompt, speaker role, degree of upsetness, and apology level. Because of the relatively large sample size, we considered p-values less than .01 to be statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

Of the 1845 panel members invited to participate, 1209 responded (65.5%). The median completion time was 5 minutes. Twenty-one participants had completion times of less than 2 minutes; these participants were discarded resulting in a final sample size of 1188 (64.4% of those invited). We made this decision based on the length of the survey and the average response time for other participants.

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants’ average (mean) age was 56.6 years; 73.9% identified as white, non-Hispanic, 37.2% reported high school or less as their highest level of education, and 35% reported a recent hospitalization. Comparisons of the groups defined by randomization (e.g., by speaker role, by extent of the prompt, and level of apology) using chi-square statistics revealed no statistically significant differences (i.e., p-values were not less than .01).

Table 1.

Respondent Characteristics

| Respondent characteristics | Full Sample (N=1188) N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) (range) | 56.55 (12.7) (35–91) |

| Age | |

| 35–44 | 264 (22.2) |

| 45–54 | 233 (19.6) |

| 55–64 | 371 (31.2) |

| 65+ | 320 (26.9) |

| Sex, female | 606 (51.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 878 (73.9) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 102 (8.6) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 57 (4.8) |

| 2+ Races, non-Hispanic | 31 (2.6) |

| Hispanic | 120 (10.1) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 84 (7.1) |

| High school or GED | 357 (30.1) |

| Some college, no degree | 337 (28.4) |

| College degree or beyond | 410 (34.5) |

| Income | |

| <$25,000 | 146 (12.3) |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 237 (20.0) |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 196 (16.5) |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 176 (14.8) |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 234 (19.7) |

| $150,000 and over | 199 (16.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 114 (9.6) |

| Married/living with partner | 861 (72.5) |

| Widowed / divorced / separated | 213 (17.9) |

| Employment status | |

| Working (paid employee or self-employed) | 727 (61.2) |

| Layoff / looking for work / not working (other) | 101 (8.5) |

| Retired | 301 (25.3) |

| Disabled | 59 (5.0) |

| Recent hospitalization | |

| Yes | 415 (35.0) |

| No | 772 (65.0) |

| Missing | 1 (-) |

| Self-reported health | |

| Excellent | 116 (9.8) |

| Very good | 462 (38.9) |

| Good | 424 (35.7) |

| Fair | 161 (13.6) |

| Poor | 24 (2.0) |

| Missing | 1 (-) |

Participants’ intent to speak up about each of the three breakdowns are summarized in Table 2. Overall, participants were more likely to report they would speak up about difficulty getting questions answered compared to speaking up about rudeness on the part of the aide or the slow response to the call bell.

Table 2.

Intent to Speak up by Type of Breakdown

| Type of Breakdown | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slow response to call bell N (%) |

Rude aide N (%) |

Difficulty getting questions answered N (%) |

||

| Intent to speak up | <0.0001 | |||

| Would not mention | 190 (16.0) | 136 (11.5) | 14 (1.2) | |

| Possibly would mention | 308 (25.9) | 249 (21.0) | 58 (4.9) | |

| Probably would mention | 318 (26.8) | 291 (24.5) | 157 (13.3) | |

| Definitely would mention | 372 (31.3) | 510 (43.0) | 956 (80.7) | |

Speaker Role

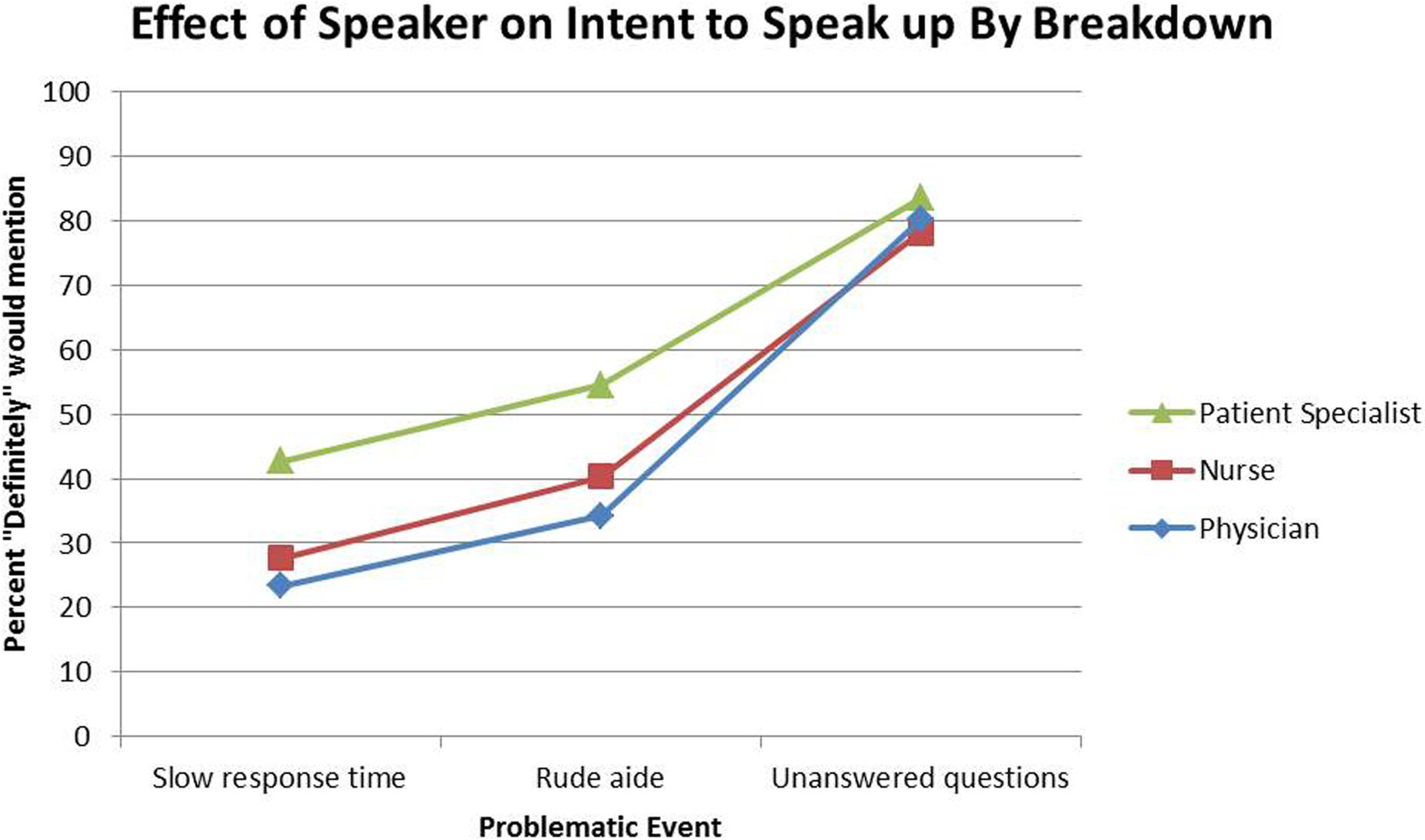

Chi-square analyses examining the effect of the role of the person inquiring (physician, nurse or patient care specialist) revealed that participants randomized to the patient care specialist were most likely to indicate they would speak up about the rude aide, followed by those randomized to the nurse; those randomized to the physician inquirer were least likely to intend to speak up about this (p<0.0001) (Figure 2). The same pattern was found for the slow response to the call bell (p<0.0001). No effect of inquirer role was detected for intent to speak up about unanswered questions (p >.10). There was some indication that having the nurse or physician ask about concerns was perceived more positively than having a patient care specialist ask. Of the participants assigned to the nurse inquirer condition 17.2% reported they would (probably/definitely) recommend the hospital; this percentage was only slightly lower for the physician inquirer condition (15.8%) but dropped to 9.95% of those in the care specialist condition (p=.0167).

Figure 2.

Effect of Speaker on Intent to Speak up by Breakdown

Wording of the Prompt

Analyses of the impact of the wording of the prompt indicated that the manipulation was effective; 57.0% of those in the expanded prompt condition agreed or strongly agreed with the “Staff in this hospital want to know if patients have any problems” compared to 44.5% of those in the intermediate and 31.0% of those in the no prompt conditions (overall chi-square p <0.0001).

We found no statistically significant effect of wording of the prompt on intent to speak up for any of the three breakdowns (p > .10), nor were there any statistically significant interactions between prompt wording and the role of the speaker (p>.28). However, we found a relatively strong effect on intent to recommend the hospital. Participants who received the extended prompt were more than twice as likely to indicate that they would recommend the hospital (18.4% probably/definitely) compared to those who received no prompt (8.8%), while those in the intermediate condition fell in between (14.7%; overall chi-square p=0.0067). The effect of prompt on intent to recommend the hospital did not vary by speaker role, however (p=.92 for interaction).

Relationship between emotional response to breakdowns and intent to speak up

Overall, more participants reported they would feel extremely upset about difficulty getting their questions answered than about the slow response to the call bell and the rude aide; 48.3% of participants reported they would be extremely upset about not getting their questions answered; 26.7% of participants would be extremely upset about the rude aide, and 11.0% would be extremely upset about the slow response to the call bell. Chi-square analyses indicated an association between the degree of feeling upset and intent to speak up for each of the three breakdowns, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Intent to Speak up by Extent of Feeling Upset

| Would Definitely Speak Up N (%) |

p-value for chi square | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow response to call bell | |||

| Extremely Upset (n=130) | 108 (83.1) | p<.0001 | |

| Very Upset (n=290) | 155 (53.4) | ||

| Somewhat Upset (n=692) | 108 (15.6) | ||

| Not at all Upset (n=73) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Rudeness | |||

| Extremely Upset (n=316) | 256 (81.0) | p<.0001 | |

| Very Upset (n=468) | 209 (44.7) | ||

| Somewhat Upset (n=368) | 42 (11.4) | ||

| Not at all Upset (n=30) | 3 (10) | ||

| Unanswered questions | |||

| Extremely Upset (n=569) | 527 (92.6) | p<.0001 | |

| Very Upset (n=429) | 335 (78.1) | ||

| Somewhat Upset (n=169) | 88 (52.1) | ||

| Not at all Upset (n=12) | 2 (16.7) | ||

Impact of apology

In the final portion of the vignette, all participants were asked to imagine that they had spoken up about the events described. Participants were randomized to receive one of three responses (full, limited or no apology). Participants who received the full apology were much more likely to report they would recommend the hospital (probably/definitely) (34.1%) compared to those in the limited apology (22.3%) or no apology (13.6%) condition; this effect was highly statistically significant (p<0.0001). There were no statistically significant interactions between apology level and degree of upsetness for any of the three care breakdowns (p>.76). Regarding interactions between speaker role and degree of upsetness, intent to recommend the hospital was similarly low regardless of speaker, across all three care breakdowns. In contrast, for participants who were less upset, those speaking with the specialist were the least likely to intend to recommend the hospital and those speaking with the nurse were the most likely, consistently across care breakdown type. However, none of these interactions were statistically significant (p>.08).

CONCLUSION

Patients and family members have unique insights into care, but are often reluctant to speak up, resulting in missed opportunities for learning and improvement. In this study we found that the nature of the prompt about care breakdowns and the extent of the apology once a breakdown had occurred both had a substantial impact on patients’ reported willingness to recommend the hospital.

Not surprisingly, the three common care breakdowns studied here were reported to be upsetting to most patients; less predictably, many who reported being very or extremely upset indicated they would not necessarily speak up. This implies that providers are likely to encounter patients who are very upset, but who have not spoken up about their distress or the precipitating event, thereby making it difficult for the provider to offer an effective response. In addition, these findings indicate that patients who do speak up are likely to be quite upset, even if, from the provider’s perspective, what has occurred is not cause for significant distress.[18] This also suggests that providers who recognize the negative emotions that underpin and stimulate some patients to speak up about breakdowns in care will be better positioned to respond fully and effectively to patient concerns.

Our efforts to identify specific strategies that hospitals might use to more effectively encourage patients to speak up yielded mixed results; the role of the person asking mattered in two of the three situations we described. It is not surprising that relatively few patients would report rudeness or a slow response to a call bell to a physician, as most patients would not see these as the physician’s responsibility. The fact that in some instances participants were most likely to speak up to the patient specialist suggests that hospitals should consider having someone who is not part of the care team inquire about care, but our finding that participants indicate they would be more likely to recommend the hospital if a nurse or physician inquired about care argues that a nurse or physician should inquire. The best answer may be to have multiple people inquire about care in order to both learn about breakdowns that patients may be reluctant to report to the care team, and to convey that frontline providers care about the patient experience.[12,14,19,20]

While the three variations in wording to inquire about care did not differentially affect intent to speak up, wording did have an impact on intent to recommend the hospital. This is an important finding which suggests that taking the time to truly inquire about care in a way that acknowledges that things can go wrong, together with a pledge to work to fix the problem, can have a substantial positive effect on patients’ ultimate evaluation of their experience.

One of the most important findings from this study is that a full apology had a strong, positive effect on intent to recommend the hospital. This is not surprising but is likely to be reassuring to providers who feel unprepared to respond to upset, dissatisfied patients and family members. Specifically, a sincere expression of regret, a statement of empathy including an acknowledgement of the impact of the event on the patient, and a commitment to preventing recurrences increased participants’ intent to recommend the hospital even after three breakdowns in care. Of note, the full apology had a beneficial impact even though it did not include an acknowledgement of responsibility. This demonstrates that in instances when providers are uncomfortable acknowledging responsibility, an apology that includes all other elements is still valuable. It is widely recognized that apologies are important for healing and resolution in the wake of medical errors;[16,17] the current findings provide evidence that a short apology can play an influential role in service recovery in less acute situations. Lazare has asserted the importance of effective apologies in a variety of situations in the medical context and beyond;[15] the growing attention to patient experience scores, and the challenges organizations face in improving scores may stimulate greater attention to and training in apology. The benefits of apology constitute a further motivation for encouraging patients to speak up if they believe they have experienced a breakdown, as speaking up creates an opportunity to apologize.

This study has strengths and limitations. The factorial survey design is a strength in that it allowed experimental control over the participants’ hypothetical experience. Experimental control of this sort is impossible to achieve in the actual hospital environment. However, this methodology also introduces a limitation, as we are unable to assess whether patients’ responses to actual events would parallel the responses provided to the hypothetical events describe here. As in any experiment, we were limited in the number of conditions we were able to test. For instance, we tested three versions of a prompt about concerns; we do not know whether other phrasings might have a significant effect on intent to speak up. We described three breakdowns in care; we do not know whether participants would respond similarly to other breakdowns, or whether we would have obtained different results had we tested each breakdown separately. Similarly, we did not test whether family members would be more likely to speak up on behalf of the patient (as compared to the patient speaking up on their own behalf); our prior work suggests this would be the case.[2] Our finding of an association between how upset a participant reported feeling and intent to speak up should be interpreted in light of the fact that emotions are inherently subjective and may be experienced differently. Although the GfK panel from which this sample was drawn large and nationally representative, it is possible that the participants differ from the general population which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Further study is warranted to more closely examine these findings among populations known to be particularly vulnerable to experiencing breakdowns and not feeling comfortable speaking up.[21]

Patient-perceived care breakdowns are common, upsetting to patients and family members, and often result in harm. Our finding that substantial numbers of participants would not speak up - even if they report being upset and even when explicitly encouraged to do so- highlights how difficult it is to persuade patients to voice their concerns. We believe that to be effective, efforts to elicit patients’ concerns must include repeated messaging, delivered via multiple channels, and reinforced by bedside providers who convey a sincere desire to know when things go wrong. Once a care breakdown is reported, an apology which includes a sincere expression of regret, empathy, and a commitment to preventing recurrences is the first and perhaps most important step in improving care.

Supplementary Material

COMPETING INTERESTS AND FUNDING

All authors have declared that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

This study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (4R18HS022757 and 1K08HS024596). The funder had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of this study.

This study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) grants #4R18HS022757 (Mazor, Gallagher, and Smith) and 1K08HS024596 (Fisher).

Footnotes

PATIENT CONSENT

Not required.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bardach NS. Raising up the voices of the closest observers of care. BMJ quality & safety 2018;27(2):96–98. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007149 [published Online First: 2017/12/09] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher K, Smith K, Gallagher T, et al. We Want to Know: Eliciting Hospitalized Patients’ Perspectives on Breakdowns in Care. Journal of hospital medicine 2017;12(8):603–09. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2783 [published Online First: 2017/08/09] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher KA, Ahmad S, Jackson M, et al. Surrogate decision makers’ perspectives on preventable breakdowns in care among critically ill patients: A qualitative study. Patient education and counseling 2016;99(10):1685–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.027 [published Online First: 2016/04/14] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giardina TD, Haskell H, Menon S, et al. Learning From Patients’ Experiences Related To Diagnostic Errors Is Essential For Progress In Patient Safety. Health affairs 2018;37(11):1821–27. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0698 [published Online First: 2018/11/06] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison R, Walton M, Manias E, et al. The missing evidence: a systematic review of patients’ experiences of adverse events in health care. International journal for quality in health care : journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care 2015;27(6):424–42. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv075 [published Online First: 2015/10/02] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iedema R, Allen S, Britton K, et al. What do patients and relatives know about problems and failures in care? BMJ quality & safety 2012;21(3):198–205. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000100 [published Online First: 2011/12/20] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law AC, Roche S, Reichheld A, et al. Failures in the Respectful Care of Critically Ill Patients. Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety / Joint Commission Resources 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2018.05.008 [published Online First: 2018/09/02] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazor KM, Kamineni A, Roblin DW, et al. Encouraging Patients to Speak up About Problems in Cancer Care. Journal of patient safety 2018. doi: 10.1097/pts.0000000000000510 [published Online First: 2018/06/30] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, et al. Toward patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2012;30(15):1784–90. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.38.1384 [published Online First: 2012/04/18] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Weingart SN, et al. Comparing patient-reported hospital adverse events with medical record review: do patients know something that hospitals do not? Annals of internal medicine 2008;149(2):100–8. doi: 149/2/100 [pii] [published Online First: 2008/07/16] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell SK, Roche SD, Mueller A, et al. Speaking up about care concerns in the ICU: patient and family experiences, attitudes and perceived barriers. BMJ quality & safety 2018;27(11):928–36. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007525 [published Online First: 2018/07/14] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Entwistle VA, McCaughan D, Watt IS, et al. Speaking up about safety concerns: multi-setting qualitative study of patients’ views and experiences. Quality & safety in health care 2010;19(6):e33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.039743 [published Online First: 2010/12/04] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frosch DL, May SG, Rendle KA, et al. Authoritarian physicians and patients’ fear of being labeled ‘difficult’ among key obstacles to shared decision making. Health affairs 2012;31(5):1030–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0576 [published Online First: 2012/05/09] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazor KM, Smith KM, Fisher KA, et al. Speak Up! Addressing the Paradox Plaguing Patient-Centered Care. Annals of internal medicine 2016;164(9):618–9. doi: 10.7326/m15-2416 [published Online First: 2016/02/10] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazare A Apology in medical practice: an emerging clinical skill. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2006;296(11):1401–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.11.1401 [published Online First: 2006/09/21] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazor KM, Greene SM, Roblin D, et al. More than words: Patients’ views on apology and disclosure when things go wrong in cancer care. Patient education and counseling 2013;90(3):341–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.010 [published Online First: 2011/08/10] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazor KM, Simon SR, Yood RA, et al. Health plan members’ views about disclosure of medical errors. Annals of internal medicine 2004;140(6):409–18. [published Online First: 2004/03/17] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams M, Maben J, Robert G. ‘It’s sometimes hard to tell what patients are playing at’: How healthcare professionals make sense of why patients and families complain about care. Health (London, England : 1997) 2018;22(6):603–23. doi: 10.1177/1363459317724853 [published Online First: 2017/08/24] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King A, Daniels J, Lim J, et al. Time to listen: a review of methods to solicit patient reports of adverse events. Quality & safety in health care 2010;19(2):148–57. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.030114 [published Online First: 2010/03/31] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyndon A, Wisner K, Holschuh C, et al. Parents’ Perspectives on Navigating the Work of Speaking Up in the NICU. Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing : JOGNN 2017;46(5):716–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.06.009 [published Online First: 2017/08/05] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher KA, Smith KM, Gallagher TH, et al. We want to know: patient comfort speaking up about breakdowns in care and patient experience. BMJ quality & safety 2019;28(3):190–97. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008159 [published Online First: 2018/10/01] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.