Abstract

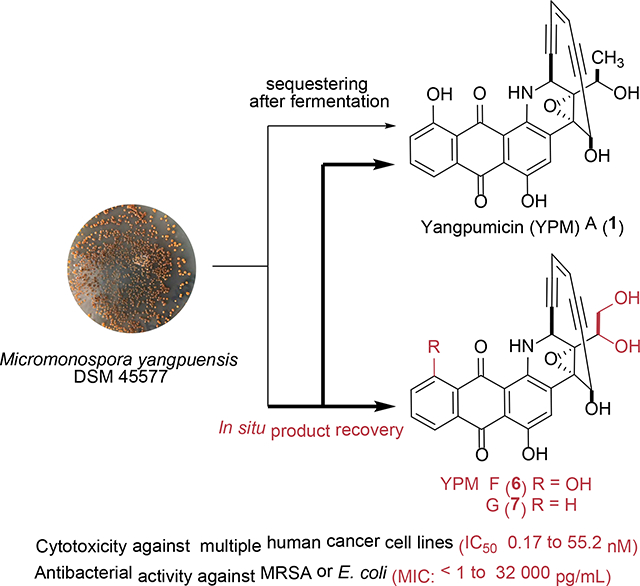

Enediyne natural products are among the most cytotoxic small molecules and thus excellent payload candidates for the development of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs). Here we report the isolation and structural elucidation of two new 10-membered anthraquinone-fused enediynes, yangpumicin (YPM) F (6) and G (7), together with five known congeners YPM A-E (1-5), from Micromonospora yangpuensis DSM 45577. YPM F (6) and G (7) showed strong cytotoxicity against the tested human cancer cell lines, as well as activity against several Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. The 1,2-diols in 6 and 7 promise to enable new linker chemistry for the development of YPM-based ADCs.

Graphical Abstract

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), combining highly toxic natural products or their derivatives as payloads with the specific binding properties of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for targeted delivery, are effective antitumor therapeutics.1, 2 The recent approval of five ADCs, including Adcetris, Kadcycla, Mylotarg, Besponsa, and Polivy, together with the > 65 ADCs currently in clinical evaluation, supports the huge potential of ADCs against various types of cancer.3, 4 For example, a recently completed phase III clinical trial using trastuzumab emtansine, consisting of a mAb trastuzumab (Herceptin) and the payload emtansine (DM1), a maytansine derivative, showed clear clinical benefits against metastatic breast cancer, when compared side-by-side with Herceptin alone.5 In addition, there is also a huge potential for using antibody-based biologics, including ADCs, to combat serious staphylococcal infections.6–7

Enediynes are the most cytotoxic small molecules known to date, and are very promising payloads in ADCs.8 Calicheamicin, a 10-membered enediyne natural product, is used as the payload for Mylotarg and Besponsa for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia or acute lymphoblastic leukemia, respectively. Another ADC consisting of an anthraquinone-fused enediyne, uncialamycin and an anti-mesothelin mAb, showed sub-nanomolar potency against mesothelin-positive lung cancer cell lines in vitro (IC50 = 0.88 nM, H226 cell line).9 Due to the facts that the payloads of many current ADCs are limited to a few natural products, such as auristatin, maytansinoid, and calicheamicin, there is an urgent need to discover new enediynes as payload candidates.10 In addition, the ADC linkers, which enable the conjugation of the payloads with mABs, play critical roles to release the payloads under varying physiological conditions to exert their cancer-killing cytotoxicity.1

A new anthraquinone-fused enediyne, yangpumicin (YPM) A (1), and the cycloaromatized enediynes YPM B-E (2-5), were previously isolated from Micromonaspora yangpuensis DSM 45577 using a genome mining approach (Figure 1).11 While 2 and 3 have been viewed as cycloaromatized metabolites of 1, on the basis of previous studies of dynemicin A as a prototype anthraquinone-fused enediyne,12 the isolation of 4 and 5 would suggest the presence of an additional YPM enediyne, which was not previously isolated due to the extremely low titers of YPMs.11 The addition of solid-phase adsorbents during fermentation has increased the production of many valuable microbial natural products, such as anticancer agents epothilone D and leinamycin, and two enediyne natural product dynemicin A and esperamicin A1, by avoiding certain feedback inhibition or the cytotoxicity of the products.13–17 We have also significantly increased the production of tiancimycins A and D by adding microporous resins to the culture of the wild-type and ribosome-engineered mutants of Streptomyces sp. CB03234.18, 19

Figure 1.

Structures of anthraquinone-fused enediynes dynemicin A, uncialamycin, tiancimycin A and yangpumicins. YPM F (6) and G (7) were identified in this study.

In the current study, we added macroporous resins into the fermentation medium, which significantly improved YPMs titer and enabled the isolation and evaluation of two new YPM congeners, YPM F (6) and YPM G (7). The newly isolated YPMs, featuring a 1,2-diol functionality, provide a new opportunity to develop linker chemistry for the next generation of anthraquinone-fused enediyne-based ADCs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Encouraged by the successful titer improvement for tiancimycins A and D, we adopted the same strategy in the fermentation of M. yangpuensis DSM 45577. Addition of either macroporous resin HP2MGL or SP825L to the fermentation culture after 48 h led to a significant increase of YPMs, while resin addition at the beginning of fermentation was detrimental for their production (Figure 2A). The reason might be the sequestering of certain nutrients by the added resins, which inhibited the initial growth of the producing strain.12 Since the cycloaromatized products of anthraquinone-fused enediynes possess UV spectra distinct to their corresponding enediyne forms, the observation of two new compounds 6 and 7, with similar UV spectra to YPM A (1), suggested the production of new YPM congeners in their enediyne forms. A large-scale fermentation (15 L) of M. yangpuensis DSM 45577 was thus performed to isolate and establish the structures of 6 and 7.

Figure 2.

Structure elucidation of YPM F (6) and YPM G (7). (A) HPLC analysis of the YPMs 1-7 in M. yangpuensis DSM 45577 with or without the addition of the resins. (I) Fermentation without resins; (II) Addition of 3% (w/v) HP2MGL resins in the fermentation medium at the beginning of the fermentation; (III) Addition of 3% (w/v) HP2MGL resins into the fermentation medium at 48 h; (IV) The addition of 3% (w/v) SP825L resins into the fermentation medium at 48 h. (B) Key 1H−1H COSY (red) and HMBC (blue arrow) correlations of 6 and 7. (C) Key ROESY correlations (green arrow) of 6 and 7.

YPM F (6) was isolated as a purple powder. The molecular formula of YPM F (6) was established as C26H17NO8 by HRESIMS, differing from the molecular formula of 1 by one oxygen atom (Figure S1). The 1H and 13C NMR data of 6 were similar to YPM A (1) (Table 1 and Figures S5–S6).10 The methyl doublets in YPM A (1) [δH 1.46 (3H, d, J = 6.3 Hz, Me-27)] was substituted by the resonances of a hydroxymethyl group [δH 3.72 (dd, J = 11.4, 7.1 Hz, H-27a), 3.84 (dd, J = 11.6, 2.7 Hz, H-27b); δC 65.3 (CH2, C-27)]. This assignment was supported by the 1H−1H COSY correlation between H-26 and H-27, as well as the HMBC correlations from H-27 to C-26 and C-25 (Figure 2B). The complete structure of 6 was assigned based on 1H−1H COSY, HSQC, and HMBC data (Figures 2B and S7–S9). The ROESY of 6 revealed the correlation between H-26 and H-17, which was the same as the ROESY correlation in YPM A (1) (Figure S10). The 1,2-diol functionality in 6 is unprecedented in anthraquinone-fused enediynes (Figure 1) and could be exploited to develop new linker chemistry for facile conjugation of 6 to mABs for the next generation of anthrquinone-fused enediyne-based ADCs.20

Table 1.

1H NMR (6, 500 MHz; 7, 600 MHz) and 13C NMR (6, 125 MHz; 7, 150 MHz) Data of Compounds 6 and 7 in Acetone-d6

| position | 6 |

7 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, type | δH (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 10.25, br s | 10.16, d (4.0) | ||

| 2 | 145.4, C | 145.0, C | ||

| 3 | 111.6, C | 111.8, C | ||

| 4 | 192.3, C | 188.3, C | ||

| 5 | 117.0, C | 135.9, C | ||

| 6 | 163.0, C | 127.7, CH | 8.31, m | |

| 7 | 123.3, CH | 7.28, br d (7.6) | 133.7, CH | 7.89, td (7.5, 1.4) |

| 8 | 138.0, CH | 7.80, m | 134.2, CH | 7.93, td (7.5, 1.4) |

| 9 | 119.6, CH | 7.83, m | 127.1, CH | 8.33, m |

| 10 | 136.2, C | 135.5, C | ||

| 11 | 183.1, C | 183.7, C | ||

| 12 | 113.7, C | 113.9, C | ||

| 13 | 156.9, C | 156.9, C | ||

| 14 | 131.6, CH | 8.72, s | 131.5, CH | 8.74, s |

| 15 | 137.1, C | 136.4, C | ||

| 16 | 64.1, C | 64.2, C | ||

| 17 | 65.3, CH | 5.36, s | 65.4, CH | 5.36, d (4.7) |

| 18 | 100.3, C | 100.4, C | ||

| 19 | 90.8, C | 90.8, C | ||

| 20 | 123.9, CH | 6.04, d (9.9) | 123.9, CH | 6.02, dd (9.9, 0.4) |

| 21 | 124.6, CH | 5.96, d (10.0) | 124.6, CH | 5.94, dt (9.9, 0.5) |

| 22 | 88.5, C | 88.5, C | ||

| 23 | 99.2, C | 99.3, C | ||

| 24 | 44.8, CH | 5.23, d (3.9) | 44.8, CH | 5.22, dd (4.4, 1.6) |

| 25 | 76.7, C | 75.6, C | ||

| 26 | 69.7, CH | 4.37, m | 69.8, CH | 4.36, m |

| 27 | 65.3, CH2 | 3.72, dd (11.4, 7.1) | 65.4, CH2 | 3.73, m |

| 3.83, dd (11.6, 2.7) | 3.84, d (11.6) | |||

| 6-OH | 12.18, br s | |||

| 13-OH | 12.58, br s | 13.30, br s | ||

| 17-OH | - | - | ||

| 26-OH | 5.90, br s | 5.82, d (4.9) | ||

| 27-OH | 4.73, br s | 4.64, d (4.6) | ||

YPM G (7) was also isolated as a purple powder with a molecular formula of C26H17NO7, by HRESIMS (Figure S1). The high similarity between the 1H and 13C NMR data of 7 with 1 and 6, suggested that 7 is also an anthraquinone-fused enediyne (Table 1, Figures S12-S15). The additional aromatic carbon C-6 (δ 127.7) of 7 suggested the lack of a phenolic hydroxy group at C-6, as found in 6. This assignment was confirmed by the presence of a spin system from H-6 to H-9 as shown by COSY analysis. The presence of HMBC correlations of 26-OH to the carbon resonances at δ 79.7 (C-25) and 69.7 (C-26) were observed, which supported the connection of 1, 2-diol unit to the enediyne core (Figure S19). This connection was consistent with the ROESY correlation between H-26 and H-17, which was the same with the ROESY correlations observed in 1 and 6 (Figure S20).10 The complete structure of 7 was further assigned based on 1H−1H COSY, HSQC, and HMBC data (Figures 2B). Based on the same biosynthetic origin of 6 and 7 with 1, as well as their ROESY correlations, the absolute configuration of 6 and 7 was thus suggested to be the same as 1. This was also supported by the CD curves of 6 and 7 (Figure S2), which were similar to that of YPM A (1).

The cytotoxicity of the YPM congeners 6 and 7 was measured using MTT assay, with both YPM A (1) and the clinically used anticancer agent mitomycin as controls (Table 2 and Figure S23).21 All the tested YPM congeners 1, 6 and 7 showed sub-nanomolar potency against human non-small lung cancer cell A549 and lymphoma tumor cell Jurkat, while compounds 1 and 6 were at least 10-fold more potent than 7 against colon tumor cell line Caco-2 or breast tumor cell line SKBR-3. YPM G (7) lacks the hydroxy group on C-6 found in 1 and 6. The observed cytotoxicity among the YPMs is consistent with the previously report that the increasing the oxidation state on the anthraquinone in tiancimycins was proportional to an increase in their cytotoxicity.22 In addition, 6 exhibited more potent cytotoxicity than 1 after 8 h incubation in the rapid killing assay against SKBR-3 (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity of YPM F and G against Selected Human Cancer Cell Lines.a

| cell lines | cancer type | IC50 (μM) Mitomycin | IC50 (nM) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YPM A (1) | YPM F (6) | YPM G (7) | |||

| CaCo2 | colon | 5.80 ± 0.80 | 3.40 ± 0.40 | 3.16 ± 0.07 | 55.20 ± 6.70 |

| Jurkat | lymphoma | 0.43 ± 0.13 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.62 ± 0.46 |

| A549 | lung | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.09 | 3.41± 0.49 |

| SKBR-3 | breast | 1.00 ± 0.20 | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 2.56 ± 0.96 | 24.20 ± 6.00 |

The IC50s were determined by computerized curve fitting using GraphPad Prism.

Figure 3. Killing of SKBR-3 cells by YPMs.a.

aEach point represents the mean ± SD of results from three replicates, and the curve fitting using GraphPad Prism.

The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of compounds 1, 6 and 7 against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, methicillin-resistant S. aureus and Escherichia coli isolated from local hospitals, were determined using a broth dilution assay in 96-well plates, with vancomycin as control (Table 3). For the tested S. aureus strains, YPM A (1) and F (6) exhibited at least 106-fold more potency (< 1 pg/mL) over vancomycin (1 μg/mL), while YPM G (7) exhibited MICs of 2 pg/mL (Figure S24). While all were active against Escherichia coli, 6 was more potent than both 1 and 7 under the conditions tested. The observed strong antibacterial activities of YPMs were consistent with those of uncialamycin, which was suggested to be a potential antibiotic lead against serious infectious diseases, such as cystic fibrosis.16

Table 3.

The MICs of YPMs against S. aureus ATCC 29213, MRSA and Escherichia coli Using the Microbroth Dilution Method in Comparison with Vancomycin.

| strain | MIC (μg/mL) vancomycin | MIC (pg/mL) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YPM A (1) | YPM F (6) | YPM G (7) | ||

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | 1 | < 1 | < 1 | 2 |

| MRSA | 1 | < 1 | < 1 | 2 |

| Escherichia coli | > 16 | 128 | 32 | 3.2 × 104 |

In conclusion, the structures and preliminary biological evaluation of two new enediynes, YPM F (6) and G (7), were reported. Both compounds exhibited potent cytotoxicity against several human cancer cell lines and strong inhibitory effects against the tested bacteria. They may be developed into useful drug leads in ADCs against cancer or serious infectious diseases. The newly isolated YPMs feature an unprecedented 1,2-diol functionality among the isolated anthraquinone-fused enediynes. Since the diols can be covalently linked to the aldehyde by photocatalytic acetalization,23 YPMs may provide a new opportunity to develop certain linker chemistry for enediyne-based ADCs.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General experiment procedures

All chemical and biological regents used in this study were from common commercial sources, unless otherwise specified. CD spectra were recorded on J-815 from JASCO. HRMS spectra were recorded on an LTQ-ORBITRAP-ETD instrument. NMR spectra were acquired using 500 MHz or 600 MHz Brucker spectrometers. Chemical shifts were reported in ppm relative to acetone-d6 (δH = 2.05 ppm) or DMSO-d6 (δH = 2.50 ppm) for 1H NMR and acetone-d6 (δC = 29.84, 206.26 ppm) or DMSO-d6 (δC = 39.53 ppm) for 13C NMR spectroscopy. Column chromatography was carried out on Sephadex LH-20 (GE Healthcare). YPMs were analyzed on a Waters high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a PDA detector and an ACQUITY HPLC (Waters), C18 column (2.7 μm, 4.6 mm × 50 mm, Waters). The mobile phase consisted of buffer A (ultrapure H2O containing 0.1 % HCOOH and 0.1 % CH3CN) and buffer B (chromatographic grade MeOH containing 0.1 % HCOOH) was applied at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. A linear gradient program (60 % buffer A and 40 % buffer B to 50 % buffer A and 50 % buffer B for 2 mins, 50 % buffer A and 50 % buffer B to 0 % buffer A and 100 % buffer B for 5 mins, followed by 60 % buffer A and 40 % buffer B for 5 mins) was applied to detect YPMs at 539 nm. Semi-preparative reversed phase-HPLC (RP-HPLC) was performed using a Waters 1525 Binary HPLC pump equipped with a Waters 2489 UV/Visible detector and using a Welch Ultimate XP-Phenyl column (10 × 250 mm, 5 μm).

Fermentation, Extraction, and Isolation

M. yangpuensis DSM 45577 was similarly maintained and cultured in the previous report, with a few modifications.11 In brief, the strain was cultured in 250-mL baffled flasks containing 50 mL of tryptic soy broth. The production medium contained (per liter) soluble starch 10 g, Pharmamedia 5 g, CuSO4 0.05 g, NaI 5 mg, CaCO3 2 g, pH adjusted to 7.2 before autoclaving. In the small-scale fermentation, 5 mL of seed culture (10 vol %) was transferred to production medium (50 mL/250 mL) and cultured for 9–11 days at 30 °C and 230–250 rpm. The macroporous resins HP2MGL or SP825L (3%, w/v) were added into production medium at the beginning of the fermentation or at 48 h of fermentation. The amount of resin added was 6 g (wet weight) per 100 mL fermentation broth. The macroporous resins SP825L were used for large scale fermentation, and were added at 48 h of fermentation.

For the large-scale fermentation, a total of 15 L fermentation broth were obtained by using baffled flasks (2 L, 12 × 400 mL) and fermentation tanks (3 L, 5 × 2 L). The resins containing YPMs were separated by centrifugation or filtration through a metal sieve (60 mesh), washed with H2O and dried on air at room temperature. Then the crude YPMs were extracted by MeOH (3 × 2 L), and concentrated under vacuum. After the crude extracts were partitioned in 2 L of EtOAC : H2O (1 : 1) for three times, the ethyl acetate fractions were combined and concentrated under vacuum. Subsequently, the crude extracts were further partitioned in MeOH : Hexane (1 : 1) (3 × 1 L). The MeOH extracts were then concentrated under vacuum to afford the crude extracts (4.33 g). It was then dissolved in 20 mL of MeOH and subjected to Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography. Four fractions (Fr.1−Fr.4) were obtained using MeOH as eluent, which were concentrated under vacuum to yield 2.5 g, 1 g, 0.25 g, and 14.7 mg of crude products, respectively. Fr.3 was further purified on Sephadex LH-20 to yield 9 fractions (Fr. 3.1−Fr. 3.9). Fr.3.9 was further separated using semi-preparative HPLC to afford 6 (15.5 mg) and 7 (5.6 mg).

Physicochemical properties of YPM F and G

YPM F (6): purple powder; [α]D25 +3400 (C = 0.001, MeOH); UV (MeOH), 236 nm, 255 nm, 549 nm, 586 nm, see Figure S2; 1H NMR (500 MHz, acetone-d6) and 13C NMR (125 MHz, acetone-d6) data, see Table 1; HRESIMS m/z 472.1028 [M + H]+ (calcd for the [M + H]+ ion at m/z 472.1032).

YPM G (7): purple powder; [α]D25 +1900 (C = 0.001, MeOH); UV (MeOH) 256 nm, 539 nm, 556 nm, see Figure S2; 1H NMR (600 MHz, acetone-d6) and 13C NMR (150 MHz, acetone-d6) data, see Table 1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) and 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) data, see Table S1. HRESIMS m/z 472.1028 [M + H]+ (calcd for the [M + H]+ ion at m/z 472.1032).

In vitro Cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of YPMs was evaluated by the MTT assay. In brief, the three human tumor cell lines were seeded at a density of 2,000 to 4,000 cells per well in 96-well plates (Corning, Germany). After 24 h, cells were treated with different concentrations of the tested compounds. After further incubation for 72 h, the cell survival was determined by addition of Cell Counting Kit-8 solution (10 μL/well). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. For rapid killing experiment, the cells were only further incubated for 8 h, and the cell survival was similarly determined.

Antibacterial Assay

YPMs were tested for antibacterial activity against MRSA, S. aureus ATCC 29213 and E. coli. The MICs were determined using broth dilution assay.24 The bacterial strains were cultured overnight and diluted to 106 CFU/mL in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. YPMs were dissolved in DMSO, serially diluted to 20 different concentrations (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 and 512 ng/mL; 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 and 512 pg/mL) using LB broth on the 96-well plate. Vancomycin was dissolved in DMSO, serially diluted to 10 concentrations (0.03125–16 μg/mL) using LB broth on each 96-well plate. Then 100 μL LB broth containing YPMs or vancomycin and 100 μL of bacterial solution were mixed per well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. Finally, 50 μL resazurin was added into each well to visualize the result. YPMs and vancomycin were tested in duplicate on each 96-well plate.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by NSFC grants 81473124 (to Y.H.), 81872779 (to X. Y.) and 81530092 (to Y.D.), the Chinese Ministry of Education 111 Project B0803420 (to Y.D.), NIH grant GM115575 (to B.S.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (CSU) 2018zzts878 (to Zilong Wang).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information.

Experimental details, HRMS, CD spectra, 1D and 2D NMR spectra of compounds 6 and 7

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

REFERENCES

- (1).Beck A; Goetsch L; Dumontet C; Corvaia N Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov 2017, 16, 315–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Nicolaou KC; Rigol S Acc. Chem. Res 2019, 52, 127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lambert JM; Berkenblit A Annu. Rev. med 2018, 69, 191–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).FDA approves first chemoimmunotherapy regimen for patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. U.S. Food and Drug Administration press-announcements; Web site. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-chemoimmunotherapy-regimen-patients-relapsed-or-refractory-diffuse-large-b-cell (accessed July 12, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- (5).von Minckwitz G; Huang CS; Mano MS; Loibl S; Mamounas EP; Untch M; Wolmark N; Rastogi P; Schneeweiss A; Redondo A; Fischer HH; Jacot W; Conlin AK; Arce-Salinas C; Wapnir IL; Jackisch C; DiGiovanna MP; Fasching PA; Crown JP; Wulfing P; Shao Z; Rota Caremoli E; Wu H; Lam LH; Tesarowski D; Smitt M; Douthwaite H; Singel SM; Geyer CE Jr.; Investigators KN Engl. J. Med 2019, 380, 617–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lehar SM; Pillow T; Xu M; Staben L; Kajihara KK; Vandlen R; DePalatis L; Raab H; Hazenbos WL; Morisaki JH; Kim J; Park S; Darwish M; Lee BC; Hernandez H; Loyet KM; Lupardus P; Fong R; Yan D; Chalouni C; Luis E; Khalfin Y; Plise E; Cheong J; Lyssikatos JP; Strandh M; Koefoed K; Andersen PS; Flygare JA; Wah Tan M; Brown EJ; Mariathasan S Nature 2015, 527, 323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sause WE; Buckley PT; Strohl WR; Lynch AS; Torres VJ Trends. Pharmacol. Sci 2016, 37, 231–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Shen B; Hindra; Yan X; Huang T; Ge H; Yang D; Teng Q; Rudolf JD; Lohman JR Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2015, 25, 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Chowdari NS; Pan C; Rao C; Langley DR; Sivaprakasam P; Sufi B; Derwin D; Wang Y; Kwok E; Passmore D; Rangan VS; Deshpande S; Cardarelli P; Vite G; Gangwar S Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2019, 29, 466–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).de Goeij BE; Lambert JM Curr. Opin. Immunol 2016, 40, 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Yan X; Chen JJ; Adhikari A; Yang D; Crnovcic I; Wang N; Chang CY; Rader C; Shen B Org. Lett 2017, 19, 6192–6195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Nicolaou KC; Dai W-M Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 1991, 30, 1387–1416 [Google Scholar]

- (13).Phillips T; Chase M; Wagner S; Renzi C; Powell M; DeAngelo J; Michels PJ Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2013, 40, 411–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Arslanian RL; Parker CD; Wang PK; McIntire JR; Lau J; Starks C; Licari PJ J. Nat. Prod 2002, 65, 570–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hara M; Asano K; Kawamoto I; Takiguchi T; Katsumata S; Takahashi K; Nakano HJ Antibiot (Tokyo) 1989, 42, 1768–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lam KS; Veitch JA; Lowe SE; Forenza S J. Ind. Microbiol 1995, 15, 453–456. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lam KS; Gustavson DR; Veitch JA; Forenza S J. Ind. Microbiol 1993, 12, 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Liu L; Pan J; Wang Z; Yan X; Yang D; Zhu X; Shen B; Duan Y; Huang Y J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2018, 45, 141–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Zhuang Z; Jiang C; Zhang F; Huang R; Yi L; Huang Y; Yan X; Duan Y; Zhu X Biotechnol. Bioeng 2019,116, 1304–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Notz W; List B J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 7386–7387. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ohashi R; Takahashi F; Cui R; Yoshioka M; Gu T; Sasaki S; Tominaga S; Nishio K; Tanabe KK; Takahashi K Cancer. Lett 2007, 252, 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yan X; Chen JJ; Adhikari A; Teijaro CN; Ge H; Crnovcic I; Chang CY; Annaval T; Yang D; Rader C; Shen B Org. Lett 2018, 20, 5918–5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Yi H; Niu L; Wang S; Liu T; Singh AK; Lei A Org. Lett 2016, 19, 122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Wiegand I; Hilpert K; Hancock RE Nat. Protoc 2008, 3, 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.