Despite the numerous organs that may be involved with sarcoidosis and the variable presentations of the disease, the indications for the treatment of sarcoidosis can be boiled down to only two: fear of danger and significant impairment in quality of life. This maxim was put forward by one of the coauthors (AW) and espoused at a World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous meeting a few years ago.

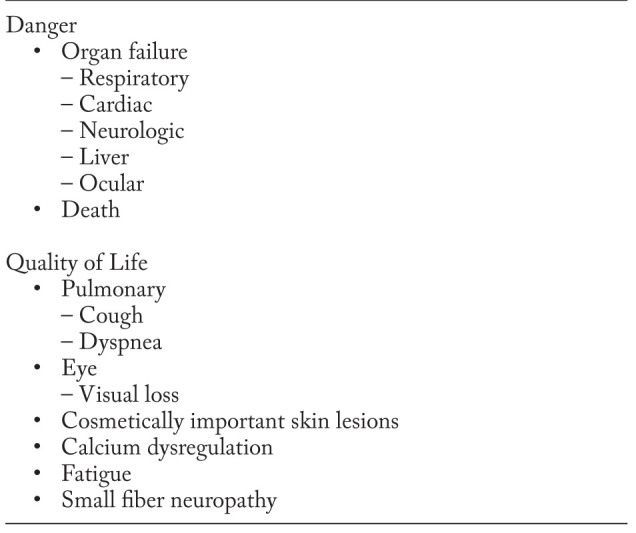

At first glance, one could argue that the indication for sarcoidosis therapy is primarily to decrease the granuloma burden and/or improve physiology or organ function impaired by granulomatous inflammation. However, a critical examination of this issue suggests that this is not the case. The granulomatous inflammation of sarcoidosis may not cause a significant physiologic derangement nor result in a significant reduction in quality of life (1). Common clinical situations where this is the case include asymptomatic bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (2, 3), and liver sarcoidosis, which requires treatment less than 12% of the time (4). Even when the granulomatous inflammation of sarcoidosis does cause physiologic abnormalities, they are often minor (4-6) and do not always lead to appreciable symptoms (6). In addition, the correlation between pulmonary dysfunction and pulmonary symptoms is poor in pulmonary sarcoidosis (7-9). Over time, the sarcoidosis community has embraced this concept, and the logic of basing the treatment of sarcoidosis on potential danger and/or quality of life impairment has solidified. Table 1 lists the examples of danger and quality of life indications for treatment in sarcoidosis patients.

Table 1.

Indications for treating sarcoidosis

It is important to understand that danger is most accurately recognized by the health care provider, based on knowledge of published outcome data, whereas only the patient has a complete grasp of their individual loss of quality of life (8). These considerations have a major impact on doctor-patient dynamics. Treatment decisions made in order to minimize danger can reasonably be based on medical experience, supplemented by the evidence-base. By contrast, interventions to address loss of quality are more likely to be successful if the patient has a very major role, both in decisions to institute therapy and changes in treatment titrated against symptomatic benefits.

In general, recommendations concerning sarcoidosis treatment indications have focused on specific situations. For example, corticosteroid therapy has been studied in pulmonary disease and shown to improve lung function for those with parenchymal lung disease on chest x-ray (2, 10). Reduced lung function and the presence of pulmonary fibrosis on chest imaging has been associated with increased mortality (11, 12). However, most patients treated for pulmonary sarcoidosis have only mild to moderate reduction in lung function. In those cases, the major indication for treatment is dyspnea (13). The recommendation to initiate corticosteroid therapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis (14, 15) is therefore far more frequently based on quality of life issues rather than danger. In regards to danger from respiratory disease, there has been a focus on use of third line treatments for patients with advanced pulmonary disease (16, 17). Patients with advanced disease have often failed therapy with corticosteroids alone. These represent up to ten percent of chronic patients see in sarcoidosis clinics (18).

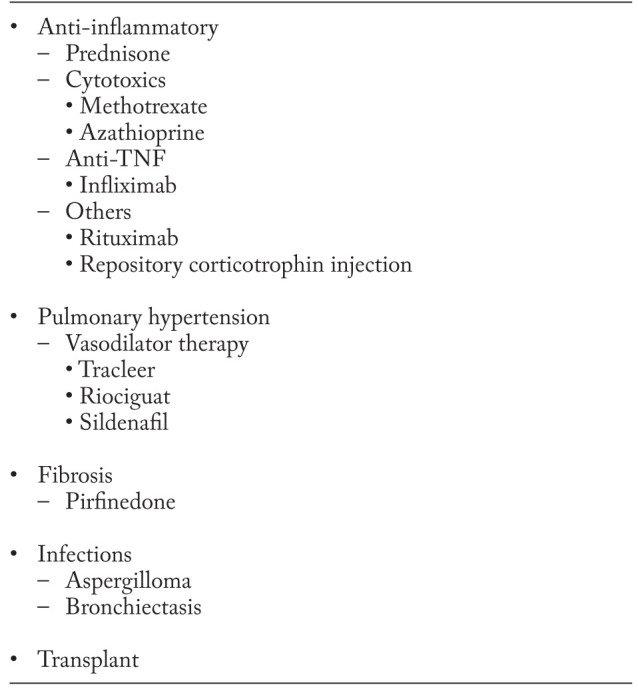

While anti-inflammatory therapies have a role in treating some aspects of sarcoidosis, other treatment regimens that are not anti-granulomatous may also be important to prevent danger or improve quality of life. Table 2 lists the treatment strategies for respiratory failure. Although anti-inflammatory agents have been widely studied for pulmonary disease and evidence based recommendations have been made (15), some causes of respiratory therapy in sarcoidosis do not respond to anti-inflammatory therapy. For danger, these include pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary fibrosis, and myceotma that may not respond to anti-inflammatory therapy alone (19-21).

Table 2.

Treatment of respiratory failure

Fear of danger from cardiac sarcoidosis has led to specific recommendations regarding screening (22). In patients with no known cardiac disease, routine screening ranges from asking about symptoms to additional testing such as electrocardiogram, Holter monitoring, and echocardiography (22, 23). While each of these tests has low sensitivity, the combination increases the sensitivity for detecting cardiac sarcoidosis while sacrificing specificity (24). Given the fears of sudden death from cardiac sarcoidosis, many clinicians have a low threshold for performing these studies.

One paradox concerning the treatment of sarcoidosis is that corticosteroids may improve quality of life by lessening granulomatous inflammation but may also worsen quality of life because of drug side effects (25). This may prompt consideration of corticosteroid steroid sparing agents for the treatment of sarcoidosis.

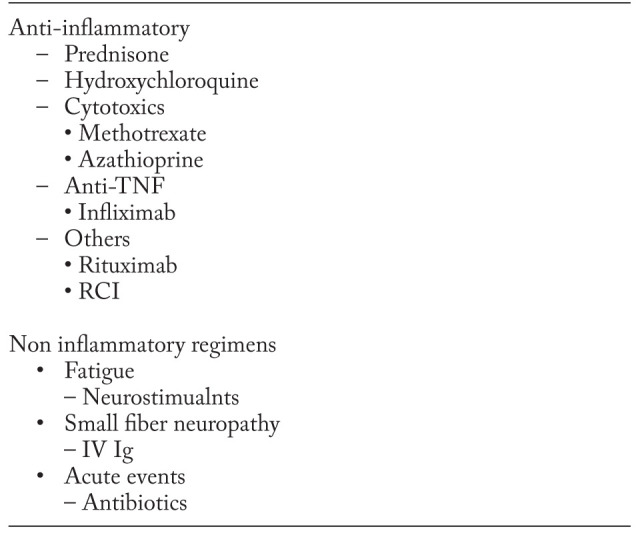

For some aspects of quality of life, anti-inflammatory treatments may have a limited role and be less effective than alternative treatments. For example, fatigue was found to less frequent in sarcoidosis patients treated with hydroxychloroquine than those treated with corticosteroids (26). However, a significant proportion of sarcoidosis patients receiving hydroxychloroquine still complained of fatigue. In some patients with small fiber neuropathy and/or cognitive failure, monoclonal antibody anti-TNF therapy has been reported as helpful (27). Sarcoidosis associated fatigue which persisted despite anti-inflammatory therapy still responded to neurostimulants (28, 29). Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy can be effective in relieving symptoms in some patients with small fiber neuropathy (30). Patients with fibrotic sarcoidosis may develop airway disease with associated infections including bacterial and fungal infections (21, 31). Patients often respond to antibiotic therapy with improved symptoms, including less cough.

While there has been much focus on developing new anti-inflammatory therapies for sarcoidosis, there have been relatively few studies directed at improving non-granulomatous aspects of the disease, many of which adversely affect quality of life. The application of Wells law orients clinicians as well as researchers to focus on the real reasons we treat patients.

Table 3.

Treatment to improve quality of life

References

- 1.Judson MA. Quality of Life Assessment in Sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36(4):739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pietinalho A, Tukiainen P, Haahtela T, et al. Oral prednisolone followed by inhaled budesonide in newly diagnosed pulmonary sarcoidosis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Chest. 1999;116:424–431. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romer FK. Presentation of sarcoidosis and outcome of pulmonary changes. Dan Med Bull. 1982;29(1):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Judson MA, Boan AD, Lackland DT, et al. The clinical course of sarcoidosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in a large white and black cohort in the United States. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1885–1889. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baydur A, Alsalek M, Louie SG, et al. Respiratory muscle strength, lung function, and dyspnea in patients with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2001;120(1):102–108. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeager H, Rossman MD, Baughman RP, et al. Pulmonary and psychosocial findings at enrollment in the ACCESS study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2005;22(2):147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox CE, Donohue JF, Brown CD, et al. Health-related quality of life of persons with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2004;125(3):997–1004. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.3.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox CE, Donohue JF, Brown CD, et al. The sarcoidosis health questionnaire. A new measure of health-related quality of life. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2003;168:323–329. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1343OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson GJ, Prescott RJ, Muers MF, et al. British Thoracic Society Sarcoidosis study: effects of long term corticosteroid treatment. Thorax. 1996;51(3):238–247. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.3.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkil G, Lower EE, Baughman RP. Predictors of Mortality in Pulmonary Sarcoidosis. Chest. 2017;17:10. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh SL, Wells AU, Sverzellati N, et al. An integrated clinicoradiological staging system for pulmonary sarcoidosis: a case-cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baughman RP, Judson MA, Teirstein A, et al. Presenting characteristics as predictors of duration of treatment in sarcoidosis. QJM. 2006;99(5):307–315. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16(Sep):149–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baughman RP, Nunes H. Therapy for sarcoidosis: evidence-based recommendations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8(1):95–103. doi: 10.1586/eci.11.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baughman RP, Drent M, Kavuru M, et al. Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(7):795–802. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-402OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossman MD, Newman LS, Baughman RP, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of infliximab in patients with active pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23:201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baughman RP, Nagai S, Balter M, et al. Defining the clinical outcome status (COS) in sarcoidosis: results of WASOG Task Force. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2011;28(1):56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boucly A, Cottin V, Nunes H, et al. Management and long-term outcomes of sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension. European Respiratory Journal. 2017 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00465-2017. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nardi A, Brillet PY, Letoumelin P, et al. Stage IV sarcoidosis: comparison of survival with the general population and causes of death. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(6):1368–1373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00187410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uzunhan Y, Nunes H, Jeny F, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis complicating sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(6):1602396–2016. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02396-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(7):1305–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamzeh NY, Wamboldt FS, Weinberger HD. Management Of Cardiac Sarcoidosis in the United States: A Delphi study. Chest. 2011;141:154–162. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta D, Lubitz SA, Frankel Z, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis: diagnostic and prognostic value of outpatient testing. Chest. 2008;133(6):1426–1435. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Judson MA, Chaudhry H, Louis A, et al. The effect of corticosteroids on quality of life in a sarcoidosis clinic: the results of a propensity analysis. Respir Med. 2015;109(4):526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Kleijn WP, Elfferich MD, de Vries J, et al. Fatigue in sarcoidosis: American versus Dutch patients. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2009;26(2):92–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elfferich MD, Nelemans PJ, Ponds RW, et al. Everyday Cognitive Failure in Sarcoidosis: The Prevalence and the Effect of Anti-TNF-alpha Treatment. Respiration. 2010;80:212–219. doi: 10.1159/000314225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lower EE, Malhotra A, Surdulescu V, et al. Armodafinil for sarcoidosis-associated fatigue: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lower EE, Harman S, Baughman RP. Double-blind, randomized trial of dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride for the treatment of sarcoidosis-associated fatigue. Chest. 2008;133(5):1189–1195. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parambil JG, Tavee JO, Zhou L, et al. Efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin for small fiber neuropathy associated with sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2011;105(1):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baughman RP, Lower EE. Frequency of acute worsening events in fibrotic pulmonary sarcoidosis patients. Respir Med. 2013;107:2009–2013. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]