Abstract

Patients with sarcoidosis present with a variety of symptoms which may impair many aspects of physical and mental well-being. Traditionally, clinicians have been concerned with physical health aspects of sarcoidosis, assessing disease activity and severity with radiological imaging, pulmonary function and blood tests. However, the most reported symptom of sarcoidosis patients, fatigue, has been shown not to correlate with the most commonly used parameters for monitoring disease activity. Studies have shown poor agreement between physicians and patients in assessing sarcoidosis symptoms. This underlines the importance of patient reported outcomes (PROs) in addition to traditional outcomes in order to provide a complete evaluation of the effects of interventions in clinical trials and everyday clinical assessment of sarcoidosis. We have undertaken a systematic review to identify and provide an overview of PRO concepts used in sarcoidosis assessment the past 20 years and to evaluate the tools used for measuring these concepts, called patient reported outcome measures (PROMs). Various PROMs have been used. By categorizing these PROMs according to outcome we identified the key PRO concepts for sarcoidosis to be Health Status and Quality of Life, Dyspnea, Fatigue, Depression, Anxiety and Stress and Miscellaneous. There is no perfect sarcoidosis-specific PROM to cover all concepts and future intervention studies should therefore contain multiple complementary questionnaires. Based on our findings we recommend the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) for assessing fatigue. Dyspnea scores should be chosen based on their purpose; more research is needed to examine their validity in sarcoidosis. The Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale (MRC) can be used to screen for dyspnea and the Baseline Dyspnea Index (BDI) to detect changes in dyspnea. We recommend The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL-100) for assessing quality of life, although a shorter questionnaire would be preferable. For assessing health status we recommend the Sarcoidosis Assessment Tool (SAT), and have great expectations for this new and promising assessment tool. Supplementary to the WASOG meeting of 2011’s recommendation on assessing QoL, we recommend incorporating fatigue, dyspnea and HS assessment in clinical trials and everyday clinical assessment of sarcoidosis. (Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2017; 34: 2-17)

Keywords: sarcoidosis, questionnaires, patient reported outcome, PROM, PRO, clinical trial, clinical assessment

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a chronic multisystemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology (1). It mostly affects young and middle-aged adults and is associated with a reduced quality of life (2). Sarcoidosis presents most commonly in the lungs but may involve any organ. Patients may have symptoms related to a specific organ involvement but can also have symptoms not attributable to a specific organ, such as fatigue (1).

Traditionally, clinicians have been concerned with physical health aspects of sarcoidosis, assessing disease activity and severity with imaging, pulmonary function and blood tests. However, the patients’ concerns may be on other consequences of sarcoidosis: fatigue and social dysfunction, depression and emotional distress, and the impact these consequences exert on quality of life. The most reported symptom of sarcoidosis patients, fatigue, has been shown not to correlate with the most commonly used parameters for monitoring disease activity (3). A study by Cox et al.(4)did show that physicians experienced in treating patients with sarcoidosis had relatively poor agreement with patients in assessing the presence of sarcoidosis symptoms. A recently published study also showed a poor relation between physician global assessment and patient global assessment (5). This underline the importance of patient reported outcomes (PROs) in addition to traditional outcomes in order to provide a complete evaluation of the effects of interventions in clinical trials and everyday clinical assessment of sarcoidosis. Also, a workshop held in Maastricht, Netherlands June 2011 at World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other granulomatous disease (WASOG) meeting concluded that it is strongly recommended that all clinical sarcoidosis trials should incorporate quality of life assessment (6).

This literature review was undertaken to identify and provide an overview of patient reported outcome (PRO) concepts used in sarcoidosis assessment the past 20 years and to evaluate the tools used for measuring these concepts such as PRO instruments, questionnaires, rating scales etc. We will refer to all of these as PROMs in this review.

Methods

A literature search was conducted 10.01.2016 in the databases Medline and Embase using the Embase.com search engine. Search words “sarcoidosis/exp OR sarcoidosis OR ‘pulmonary sarcoidosis’/exp” were combined using AND with the search “dyspnoea OR dyspnea OR health status OR ‘health status’/exp OR questionnaire OR questionnaires OR fatigue OR ‘fatigue’/exp OR ‘quality of life’ OR ‘quality of life’/exp OR measurement OR assessment OR ‘outcome assessment’/exp OR ‘symptom assessment’/exp OR ‘self evaluation’/exp OR ‘quality of life assessment’/exp OR ‘clinical assessment’ OR ‘respiratory tract disease assessment’/exp OR ‘clinical assessment tool’/exp OR tool OR instrument”. The search was repeated 19.08.16 to include articles newly published. Furthermore we performed a snowball search.

Criteria for inclusion were articles in English with an available abstract published after 01.01.95. Filters activated for Language: English; Quick limits: With abstract, Humans; Publication types: Article. We also activated filters to exclude case reports, practice guidelines and systematic reviews.

After removing duplicates, we screened title and abstract or full text articles for eligibility criteria. Selection of papers was based on the following eligibility criteria: 1) the study objective was sarcoidosis and one or more identifiable PROM were used; 2) the study population consisted of only sarcoidosis patients, or included an identifiable and separately analyzed subgroup of patients with sarcoidosis; 3) the article was a full report (no case reports, editorials, poster text, letters or reviews).

Results

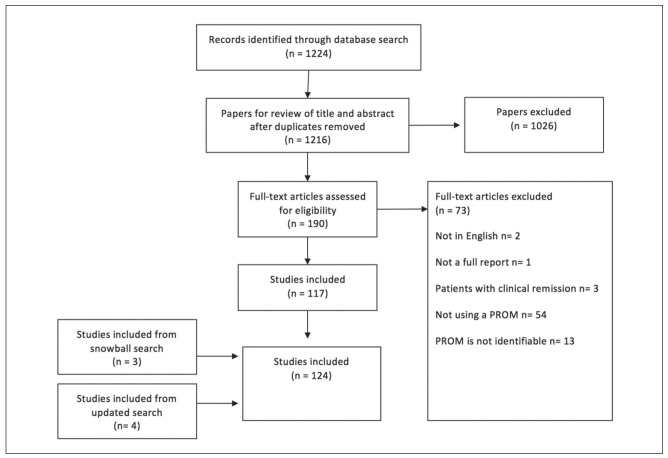

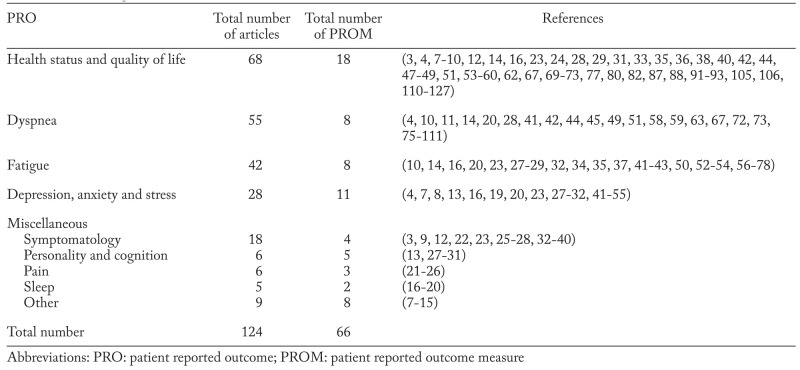

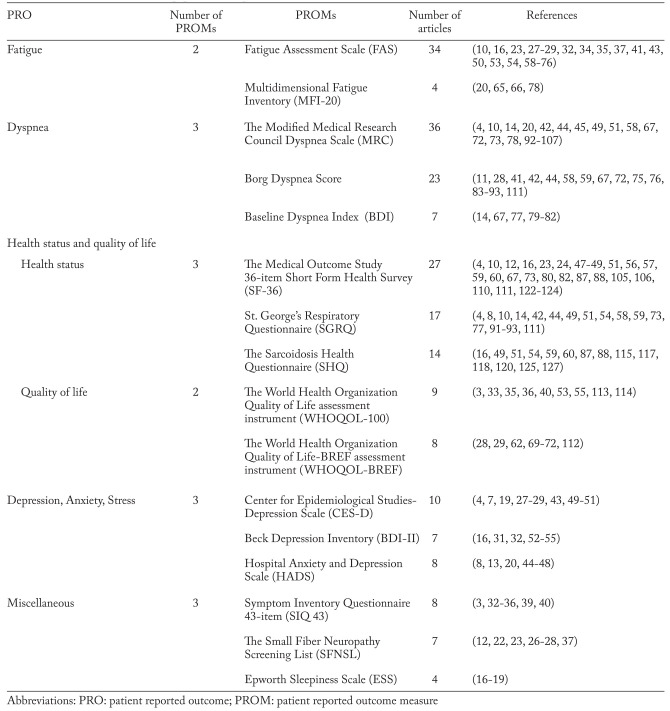

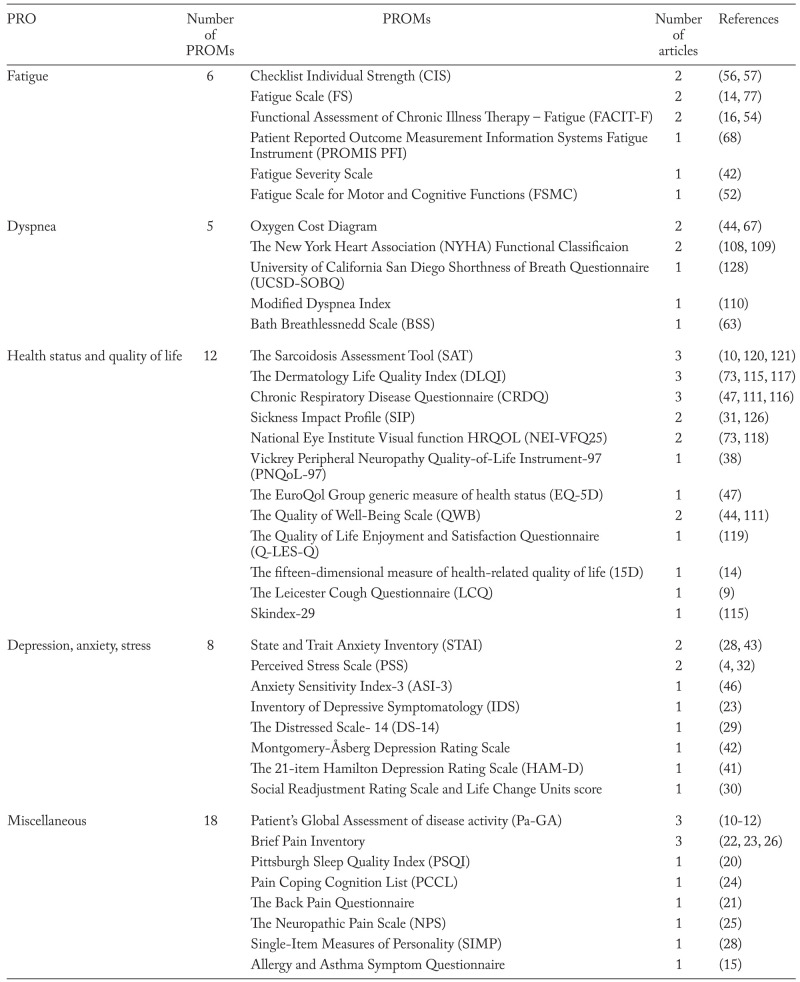

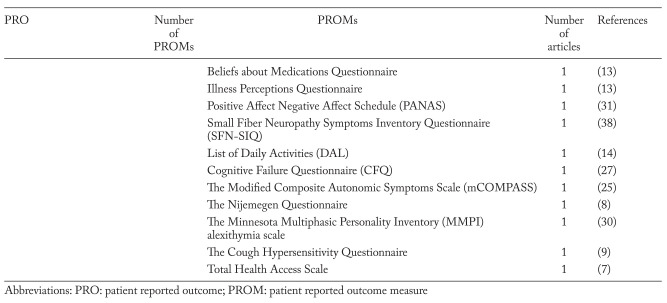

After removing duplicates we identified 1216 hits of which we included 117. Seven studies were identified and included through updated search and snowball search (Figure 1). Of the 124 studies included, we found 66 different PROMs (table 1: (3, 4, 7-127)). All PROMs were categorized by concepts. We identified five key PRO concepts in sarcoidosis: 1) Fatigue; 2) Dyspnea; 3) Health Status and Quality of Life; 4) Depression, Anxiety and Stress and 5) Miscellaneous (table 1). Due to the large number of PROMs, only those used in four or more publications are evaluated in this systematic review (table 2: (3, 4, 7, 8, 10-14, 16-20, 22-24, 26-29, 31-37, 39-107, 110-115, 117, 118, 120, 122-125, 127)). Less reported PROMs are not evaluated any further (table 3: (4, 7-16, 20-32, 38, 41-44, 46, 47, 52, 54, 56, 57, 63, 67, 68, 73, 77, 108-111, 115-121, 126, 128)). Various visual analog scales are not mentioned.

Fig. 1.

Search method

Table 1.

PRO concepts of sarcoidosis

Table 2.

PROMs evaluated in this paper, in concept, with references

Table 3.

PROMs not evaluated in this paper in concepts with references

PROMs in sarcoidosis assessment

Fatigue

Fatigue is the most reported symptom among sarcoidosis patients in several studies (35, 36, 53, 126) and it is strongly associated with a lower quality of life (35). In a study by Drent et al. no relationship was found between fatigue measured with the WHOQOL-100 energy and fatigue facet and commonly used parameters for monitoring disease activity in sarcoidosis such as S-angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) level, radiographic findings and lung function tests (3). However, patients with fatigue did suffer more frequently from dyspnea and exercise intolerance as self-reported symptoms (3). Other studies neither found a correlation between fatigue measured with FAS and lung function tests (35, 67). This suggests the need for a PROM.

The fatigue-specific questionnaires we found are listed in table 2 and table 3. Apart from the fatigue-specific questionnaires, fatigue was also assessed using the energy and fatigue subscale from the WHOQOL-100, the health status instruments SHQ, SGRQ and the vitality subscale of SF-36.

The Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS)

FAS was the most commonly used PROM for assessing fatigue, consistent with findings of de Kleijn et al. in 2009(129). FAS is a one-dimensional 10-item fatigue questionnaire consisting of five questions reflecting physical fatigue and five questions for mental fatigue, developed by Michielsen et al. (130). Each item has a five-point rating scale, ranging from “1-never” to “5-always” and FAS scores range from 10-50. FAS score <22 indicate non-fatigued persons. FAS is a reliable and valid instrument in management and follow up of patients with sarcoidosis as well as an outcome measure in clinical trials (34, 53, 62). It has been cross-validated in a Croatian sarcoidosis population (34), confirming the high internal consistency (thus reliability) and validity. It has divergent validity regarding depression measured by both Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) i.e. depression and fatigue measured by FAS are two different concepts and FAS can be used to measure fatigue distinctly from depression (specificity) (53). It is easy to complete and is not time-consuming and can be performed within 1-2 minutes (71). FAS also seems reliable and valid as an indicator for measuring dyspnea, quality of life and exercise tolerance in patients with sarcoidosis (67).

The minimal clinical important difference (MCID) of FAS in patients with sarcoidosis was estimated by de Kleijn et al. (62) in a prospective study of 443 patients of whom 321 completed follow-up. With an anchor-based methodology using the physical quality of life domain of the World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHO QOL BREF), they found the minimal clinical important difference (MCID) to be a change of 4 points. This allows FAS to be used with confidence in clinical trials or in the management of individual patients with sarcoidosis and it has been shown to be responsive to treatment (23).

The Multidimensional Fatigue Instrument (MFI-20)

MFI-20 was used in four articles (table 2). The instrument is one of the most frequently used fatigue questionnaires in Europe and it is widely used in patients with cancer, chronic fatigue syndrome and chronic inflammatory disease (65, 66). Smets et al. developed MFI-20 in 1994 (131). It is a 20-item multidimensional questionnaire consisting of five subscales of fatigue with four items each: general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced motivation, reduced activity and mental fatigue. It was developed and tested in cancer patients treated with radiotherapy, patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and different groups of healthy volunteers (psychology students, medical students, junior physicians and army recruits). The results show that the instrument has high internal consistency and validity(131). A Swedish study has validated the instrument in two cancer populations, as well as healthy individuals and confirmed that it is reliable (132). Hinz et al. (66) showed that there was a high correlation of the total scores of MFI-20 and FAS, which indicates that both questionnaires measure the same feature. The study showed that MFI-20 had good psychometric properties (reliability and convergent validity) in a sarcoidosis population. Since FAS is more popular and shorter, the authors recommended FAS for further studies.

Dyspnea

Dyspnea was the second most reported symptom among patients with sarcoidosis in a study by Wirnsberger et al., with a prevalence of 70% (39). Dyspnea is associated with poorer overall quality of life (36). In a study by Gvozdenovic et al. (14) groups of sarcoidosis patients with pulmonary involvement and pulmonary plus extrapulmonary involvement had significant dyspnea, but normal pulmonary function. This demonstrates the need to assess dyspnea as a PRO and not only as a result of lung function.

The Modified Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnea Scale

MRC was developed by Fletcher et al. in a population of 38 male patients predominantly with chronic bronchitis (133). None had sarcoidosis. It contains a set of five statements about levels of breathlessness during daily activities and the patients select the statement that most closely corresponds to their level of impairment. The five statements are graded 0-4, with 4 being the most severe dyspnea. The MRC does not include the magnitude of effort needed to evoke breathlessness and as a consequence this could theoretically reduce sensitivity in certain populations. Many patients may perform a certain task only by reducing the associated effort and thereby minimize the intensity of breathlessness, e.g. walking up stairs, only slower. This is particularly the case for younger patients with a greater exertional capacity. Modest reduction in exertional capacity might not impair an elderly person, but may have an impact on the daily life of a younger person because of higher occupational demands. The validity of MRC dyspnea scale in a population with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) has been examined by Bestall et al. (134) and was found to be good. However, it has been insinuated that the scale is not sensitive enough to detect changes (135, 136).

The Borg Dyspnea Scale

The Borg Dyspnea Scale was developed in 1982 (137). It is a 10-point scale and the patients select a point on the scale that matches their perception of dyspnea. Scores range from 0 – no impairment to 10 – severe impairment. The Borg Dyspnea Scale is easy to perform and can be administered during exercise (137). It was used together with a six-minute walk test in most of the studies identified in this review.

The Baseline Dyspnea Index (BDI)

BDI describes dyspnea in five steps integrated into three categories: degree of the functional impairment, level of the activity, and the level of effort required to develop dyspnea. Each component is graded on a five-point rating scale from 0 (‘extreme impairment’) to 4 (‘without impairment’); the total BDI score can range from 0 to 12. BDI was developed to detect changes from baseline together with the Transition Dyspnea Index (TDI) (138).

The dyspnea PROMs

In a study by Jastrzebski et al. (67) significant differences in the perception of dyspnea were confirmed between patients with sarcoidosis and healthy controls in all three dyspnea questionnaires evaluated in this review (MRC, Borg’s scale and BDI). In a study by Antoniou et al. MRC and Borg’s scale scores were both significantly different in a sarcoidosis population in comparison with healthy controls (44). This adds to the construct validity of these rating scales. They have convergent validity and thus they are sensitive to detect dyspnea in sarcoidosis populations. However evidence is lacking on whether these questionnaires are useful in detecting changes in dyspnea in sarcoidosis patients.

MRC and BDI were both used to measure differences in dyspnea between patients with sarcoidosis with only pulmonary involvement and pulmonary plus extrapulmonary involvement in another study. Only BDI could measure significant differences in dyspnea between the groups(14). Patients with pulmonary and extrapulmonary involvement may be more dyspneic because of more functional limitations. MRC does not include the associated effort necessary to perform a particular activity and this might be the reason why it, opposed to the BDI, was not able to detect the difference between the two groups.

In a study by Baughman et al. including 142 patients with sarcoidosis the range of a six-minute walk test was significantly different for each level of the MRC dyspnea score. The lower the six-minute walking distance, the higher the level of dyspnea (p<0.0001) (58). This study also found significant correlations between all three components of the St. George Respiratory Questionnaire and FAS and MRC dyspnea scores (p<0.0001 for all correlations). This is also adding to the validity of MRC dyspnea score in a sarcoidosis population.

Health Related Quality of Life (HRQL), Health Status (HS) and Quality of Life (QOL)

HRQL most often refers to HS alone but the term HRQL is also often used on the concepts HS and QOL combined, although these two concepts are different. HS reflects the impact of the disease on patients functioning and QOL reflects the patient’s evaluation of functioning (2, 139). QOL can be high in spite of a low level of functioning due to individual expectations of health, ability to cope and threshold of discomfort. In this article we will use the terms QOL and HS. Studies have shown reduced QOL in sarcoidosis patients compared to healthy controls (71). Fatigue is an important negative predictor of QOL (71).

Quality of Life

The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL- 100)

WHOQOL-100 is a generic multidimensional measure of QOL. This questionnaire is developed cross-culturally simultaneously in 15 centers around the world and contains six domains covering 24 facets and one general evaluative facet. There are four items per facet producing a total of 100 items. All items are rated on a five-point scale (from 1-5) (140). The reliability and validity of the instrument was tested in a sarcoid population and was found to be good (40). MCID of the WHOQOL-100 in a sarcoidosis population has not yet been studied. A change in score of 1 on the WHOQOL-100 is proposed as the MCID for women with early-stage breast cancer(141).

The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF assessment instrument (WHOQOL-BREF)

This questionnaire is an abbreviation of the WHOQOL-100, consisting of 26 items. It contains 24 questions on four domains and two questions on overall QOL and general health (142). Alilovic et al. have evaluated the usefulness of the WHOQOL-BREF in a sarcoidosis population of 97 patients compared to 97 healthy controls. They concluded that WHOQOL-BREF is not sufficient for the evaluation of QOL in sarcoidosis patients based on the failure to obtain any information regarding fatigue, which is the most significant symptom of sarcoidosis (112).

Health Status

The Medical Outcome Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)

SF-36 is a generic 36-item HS instrument with six domains. Scores are transformed into a 100-point scale, with higher scores indicating better HS (143). There is evidence of reliability and validity for its use among persons with various conditions, including a population with interstitial lung disease, where 9 patients had sarcoidosis (111). Construct validity of the SF-36 was confirmed by Cox et al. on a population of 120 sarcoidosis patients (4). The domains can be used together or separately. An improvement in vitality score of at least 20 points was found to be the MCID that correlated the best with improvement in other HS-measures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (144).

St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)

SGRQ is a 76-item respiratory specific questionnaire developed for measuring health in chronic airflow limitation. It contains three domains (symptoms, which measures respiratory symptoms; activities, which measures impairment of mobility or physical activity; and impacts, which measures the psychosocial impact of disease). Scores for each domain and a summary score are on a 100-point scale. Lower scores indicate better HS, the opposite of SF-36 (145). A score of 40 or greater is associated with significant impairment in respiratory health (145). Chang et al. (111) evaluated SGRQ in a population with interstitial lung disease, including sarcoidosis patients, and found good construct validity of this instrument based on correlation with pulmonary function, six minute walking distance, dyspnea rating and other HS-measures such as Quality of Well Being Scale and the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ). The construct validity of SF-36 and SGRQ was confirmed by Cox et al. in a population of 120 patients with sarcoidosis (4). Although SGRQ is a respiratory-specific health status questionnaire, a study by Gvozdenovic et al. (14) showed that patients with pulmonary plus extrapulmonary sarcoidosis had statistically and clinically significant worse health status in terms of SRGQ score than those with isolated pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire (SHQ)

The SHQ is a sarcoidosis specific 29-item health status questionnaire developed by Cox et al. (49) in 2003. It contains three domains: daily functioning, physical functioning and emotional functioning. The responses range from “all of the time” (score of 1) to “none of the time” (score of 7). Higher scores indicate better health status. It takes approximately 10 minutes to complete the SHQ. It is a reliable and validated instrument for assessing health status in sarcoidosis (49, 127), but a MCID is not yet established. The SHQ score is not divided in domains, but provides one total score containing various aspects of sarcoidosis. Therefore, Judson et al. (121) suggests that the SHQ may be insensitive to changes in specific aspects of sarcoidosis related health status such as fatigue or skin changes. This was shown in a randomized controlled cutaneous sarcoidosis trial (117), where treatment did not affect SHQ score - maybe because SHQ only has two questions related to skin symptomatology. The domain fatigue is assessed with only one item: ‘Daily Functioning – Felt you were full of energy’. Regarding the measurement of fatigue in sarcoidosis with SHQ, there is no convincing validity and reliability (129).

Depression, Anxiety And Stress

The prevalence of depression in sarcoidosis population was found to be 60% and 66% in two American studies (4, 7) compared to 42% in the American ACCESS study (146). Both fatigue and anxiety are related to depressive symptoms (43). Anxiety is less understood in sarcoidosis. A prevalence of 32% was found in a population of sarcoidosis patients screened with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (13). Anxiety was significantly correlated with symptom severity and was the main covariate of physical symptoms reported by patients with sarcoidosis in a study by Holas et al. (46).

Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D)

CES-D was developed by Radloff et al. in 1977 and was validated for use in general populations (147). It is designed to measure the presence and degree of depressive symptoms. CES-D, originally a 20-item questionnaire, has been shortened to an 11-item version by Chang et al. (7). This 11-item version was also used by Yeager et al. in the ACCESS study (146). Cox et al. (4) used the 11-item version in a sarcoidosis cohort study when validating the Sarcoidosis Health Questionnaire (49). Cronbach’s alpha for this 11-item version was 0.83 indicating a good inter-item reliability (7). A cutoff score of 9 or above was used to indicate depression. The 20-item version was used by de Kleijn et al. in two articles (28, 43) and by Ellferich et al. in two other articles (27, 29). A cutoff score of 16 or above was used to screen for depression in all these studies and Cronbach’s alpha for the 20-item version was 0.89 (28). Regarding psychometric properties apart from reliability, no information on criterion validation in a sarcoidosis population was found. From the published articles using CES-D it is difficult to draw conclusions about construct validity in a sarcoidosis population.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)

BDI-II is a 21-item self-administered measure of depressive illness in adults. Patients have to select the statement from each item that best describes their feelings the past week. Each item has four possible statement responses scored 0 to 3, and the summation score ranges from 0-63 (148). Suggested score ranges for mild depression, moderate to severe depression, and severe depression are 10–19, 20–30, and 31 or higher, respectively (149). For the 21-item version different cutoff-scores were used; 15 (31, 55), 20 (16) and 21 or above (54). The psychometric properties for this self-administered questionnaire have not been investigated fully in a sarcoidosis population.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

HADS is developed by Zigmond and Snaith (150) to detect increased degrees of anxiety and depression in somatically ill patients. It has 7 anxiety and 7 depression items scored on a 4- point scale from 0-3. It provides a sum for both anxiety and depression ranging from 0-21, with higher scores indicating more depression or anxiety. In a review, results of 747 papers using HADS are summarized, and most of them attributing good psychometric properties to the questionnaire (151). In a study by Holas et al. (46) the Cronbach’s alpha was found to be 0.86 in a population with sarcoidosis, indicating high reliability. This questionnaire has demonstrated construct validity in a study of sarcoidosis patients where strong correlations between skeletal muscle weakness, HADS score, fatigue and SF-36 were found (47). To draw conclusions on construct validity of this, we need to hypothetically assume that these are the same concepts. There is no evidence for divergent validity (test of specificity) for this questionnaire.

Miscellaneous

The Small Fiber Neuropathy Screening List (SFNSL)

Small-fiber neuropathy (SFN) is recognized as a frequent, chronic, and disabling disorder. The most common symptoms are peripheral pain, dysaesthesia and reduced temperature sensitivity, and there may also be various autonomic disturbances. Sudden death in sarcoidosis might be linked to autonomic dysfunction related to small fiber neuropathy (152). Different PROMs exist for assessing SFN in sarcoidosis such as SFN symptom inventory questionnaire, the Neuropathic Pain Scale and an autonomic symptom assessment. We found that the SFNSL is most used. These instruments are useful in screening patients for SFN but diagnostic confirmations requires a 3 mm skin biopsy and immunohistochemistry to quantify intra-epidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD) (153). SFNSL is a 21-item questionnaire to measure symptomatology related to SFN. It was developed and validated in a sarcoidosis population and the reliability and validity were good (154).

Symptom Inventory Questionnaire 43-item (SIQ 43)

This sarcoidosis specific symptom inventory was developed by Wirnsberger et al. in 1998 (39). It has been used in several studies (table 2) but was most recently used in 2007 (36). It was developed using a population of members of the Dutch Sarcoidosis Society. 1755 completed the questionnaire. It has not been standardized or validated. It was pre-tested in a population of 10 sarcoidosis patients (39). The questionnaire consist of 43 items, including questions concerning current symptoms such as chest pain, arthralgia and fatigue, symptoms at onset of the disease, duration of disease, treatment, diagnostic procedures, medical history and socio-demographic data. Most of the questions are multiple choices, sometimes giving the possibility to tick more than one answer and some of the questions are open-ended.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)

We found five studies assessing problems related to sleep quality (table 1); two different PROMs were used (table 1, table 2 and table 3). Assessing sleeping problems may be relevant in sarcoidosis because prednisolon treatment can lead to sleeping difficulties and sleep apnea can be a symptom of laryngeal sarcoidosis or neurosarcoidosis. Also, sleep apnea might occur as a comorbidity. Sleep apnea can lead to increased daytime sleepiness and is strongly related to fatigue (19, 65, 155). ESS measures the general level of daytime sleepiness as the likelihood of falling asleep in eight different situations. ESS has been proved valid in a population of 150 adult patients with various sleeping disorders (156). More studies are needed to evaluate the psychometric properties of ESS in a sarcoidosis population.

Discussion

In this systematic review we have identified all PROMs used in sarcoidosis the past 20 years (table 2 and table 3). By categorizing these instruments we have identified the most important PRO concepts (table 1). We argue that PROs should be used as endpoints in clinical trials and should also be used for assessing symptom severity and treatment responses in clinical assessment of sarcoidosis patients as many features of sarcoidosis have shown not to correlate with the most commonly used parameters for monitoring disease activity. Our review has shown that there is a lack of agreement on PRO endpoints, which is unfortunate and makes comparison between studies more difficult. We have evaluated the most used PROMs in sarcoidosis and will here provide recommendations for each PRO concept.

The most used, valid and reliable instrument for measuring fatigue is FAS. It has a cutoff score to identify the fatigued and a well-established MCID. It has been shown to be responsive to treatment, is easy to perform and not time- consuming. MFI-20 has shown good reliability and validity in a sarcoidosis population. However, FAS is shorter and more popular, and is therefore recommended.

When assessing dyspnea, the purpose of assessment needs to be clear. MRC can be used for screening, or just to report the symptom. BDI was developed together with the TDI to detect changes. It needs to be investigated whether BDI/TDI can be used in sarcoidosis. The BDI detected more severe dyspnea in functionally impaired patients with pulmonary and extrapulmonary involvement than MRC. This might be explained by the low sensitivity in the MRC or low specificity in the BDI. However, it has been pointed out that the MRC does not include the magnitude of effort needed to evoke breathlessness and many patients may perform a certain task only by reducing the associated effort as may be the case for functionally impaired patients with pulmonary and extrapulmonary involvement. The Borg’s Scale is easy to perform during exercise and can be used pre and/or after a six-minute walking test as we found most of the articles did. All dyspnea measurements were sensitive to detect dyspnea in sarcoidosis patients, but we would recommend BDI and TDI for clinical trials and for assessing changes in dyspnea in sarcoidosis outpatients.

WHOQOL-100 seems to have the highest validity in sarcoidosis in assessing QOL although a shorter questionnaire might be valuable for clinical use. Generic, respiratory and sarcoidosis-specific PROMs are available for assessing health status. The generic SF-36 is useful for assessing health status, when all aspects of the disease and possible comorbidities are wanted. SHQ has the ability to differentiate health status based on the degree of organ involvement (49). Although SGRQ is respiratory-specific it has shown to be sensitive to extrapulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis. Both SF-36 and SGRQ have demonstrated good construct validity in sarcoidosis populations and they have the advantage that domains can be used together or separately. SHQ is shorter, but might be too short to assess all aspects of sarcoidosis involvement. More studies are needed to determine the MCID in HS and QOL PROMs in sarcoidosis in order to make them more useful in clinical assessment and clinical trials Sarcoidosis Assessment Tool (SAT) is a new PROM for measuring HS. It has good construct validity (121) and Cronbach’s alpha for each SAT module was at least 0.87, which indicate excellent reliability. It has been shown that the SAT fatigue module (PROMIS PFI) has superior reliability to FAS (68). A MCID is established for each SAT module. The SAT requires approximately 5 to 10 minutes for completion and is thus appropriate for use in clinical settings. Several subscales are organ specific and can be used separately or together to measure patient’s assessment of impact of disease and response to therapy.

In conclusion, we would recommend WHOQOL-100 for assessing quality of life, although a shorter questionnaire would be preferable. For assessing HS we would like to encourage the use of the new SAT due to its good psychometric properties, established MCID and convenience in clinical trials and everyday assessment of patients. Initially it can be used together with the generic SF-36 or disease-specific SGRQ in clinical trials to further investigate and enhance its validity.

For PROMs on depression the psychometric properties in a sarcoidosis population is not thoroughly investigated. Evidence for criterion and construct validity is missing, and an evidence based cutoff score is lacking for BDI-II. Both the 11-item and 20-item version of CES- D had good reliability and there was an agreement on cutoff scores. HADS have demonstrated convergent validity with strong correlations between skeletal muscle weakness, fatigue and SF-36, but its specificity needs to be investigated. We therefore recommend CES-D.

Among the miscellaneous PROMs, the SFNSL is worth mentioning. It is a valid and reliable instrument in assessing symptoms related to SFN, which can have a huge impact on the life and health of patients and is important to detect and assess. ESS can be used when screening for sleep apnea.

The WASOG meeting of 2011 recommended that clinical sarcoidosis trials should incorporate QOL assessment. In assessing disease activity, QOL might be biased because it reflects the patient’s evaluation of functioning which depend on personal resources and feeling of empowerment and it is therefore less interesting in measuring treatment efficacy in clinical trials. HS might be a better PRO in assessing the impact of the disease on patients functioning. No single PROM can cover all aspects of the disease and we therefore recommend the use of multiple complementary questionnaires when assessing patients with sarcoidosis. We suggest that fatigue, HS and preferable dyspnea should be covered both in clinical trials and everyday assessment. Due to the high prevalence of depression we recommend screening for depression.

Conclusion

Because of the poor correlations between symptoms and traditional parameters of assessing disease activity in sarcoidosis we recommend the use of PROs. Supplementary to the WASOG meetingsof 2011’s recommendation on assessing QOL, we recommend incorporating fatigue, dyspnea and HS assessment in clinical trials and everyday clinical assessment of sarcoidosis. Our review has shown that there is a lack of agreement on PRO endpoints, which is unfortunate and makes comparison between studies more difficult. We have provided PROM recommendations for each PRO concept. Based on our findings we recommend FAS for assessing fatigue. When screening for confounding variables for fatigue such as depression or sleep apnea, CES-D or ESS can be used. Dyspnea scores should be chosen based on their purpose, and more research is needed to examine their validity in sarcoidosis. MRC can be used to screen for dyspnea and BDI to detect changes in dyspnea. We would recommend WHOQOL-100 for assessing quality of life. For assessing health status we recommend SAT, and have great expectations for this new and promising assessment tool.

References

- 1.Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet PY, Muller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2014 Mar 29;383(9923):1155–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60680-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Vries J, Lower EE, Drent M. Quality of life in sarcoidosis: Assessment and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Aug;31(4):485–93. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drent M, Wirnsberger RM, De Vries J, Van Dieijen-Visser MP, Wouters EFM, Schols AMWJ. Association of fatigue with an acute phase response in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 1999;13(4):718–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d03.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox CE, Donohue JF, Brown CD, Kataria YP, Judson MA. Health-related quality of life of persons with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2004;125(3):997–1004. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.3.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Judson MA, Mack M, Beaumont JL, Watt R, Barnathan ES, Victorson DE. Validation and important differences for the sarcoidosis assessment tool. A new patient-reported outcome measure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Apr 1;191(7):786–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1785OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baughmann RP, Drent M, Culver DA, Grutiers JC, Handa T, Humbert M, Judson MA, Lower EE, Mana J, Pereira CA, Prasse A, Sulica R, Valyere D, Vucinic V, Wells AU. Endpoints for clinical trials of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29(2):90–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang B, Steimel J, Moller DR, Baughman RP, Judson MA, Yeager H, Jr, Teirstein AS, Rossman MD, Rand CS. Depression in sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(2):329–34. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2004177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Boer S, Kolbe J, Wilsher ML. The relationships among dyspnoea, health-related quality of life and psychological factors in sarcoidosis. Respirology. 2014;19(7):1019–24. doi: 10.1111/resp.12359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinha A. Predictors of objective cough frequency in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1461–71. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01369-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judson MA, Baughman RP, Costabel U, Drent M, Gibson KF, Raghu G, Shigemitsu H, Barney JB, Culver DA, Hamzeh NY, Wijsenbeek MS, Albera C, Huizar I, Agarwal P, Brodmerkel C, Watt R, Barnathan ES. Safety and efficacy of ustekinumab or golimumab in patients with chronic sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(5):1296–307. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00000914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweiss NJ, Noth I, Mirsaeidi M, Zhang W, Naureckas ET, Hogarth DK, Strek M, Caligiuri P, Machado R, Niewold T, Garcia JGN, Pangan AL, Baughman RP. Efficacy results of a 52-week trial of adalimumab in the treatment of refractory sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2014;31(1):46–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vorselaars ADM, Crommelin HA, Deneer VHM, Meek B, Claessen AME, Keijsers RGM, Van Moorsel CHM, Grutters JC. Effectiveness of infliximab in refractory FDG PET-positive sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(1):175–85. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00227014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ireland J, Wilsher M. Perceptions and beliefs in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2010;27(1):36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gvozdenovic BS, Mihailovic-Vucinic V, Ilic-Dudvarski A, Zugic V, Judson MA. Differences in symptom severity and health status impairment between patients with pulmonary and pulmonary plus extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2008;102(11):1636–42. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilsher M, Hopkins R, Zeng I, Cornere M, Douglas R. Prevalence of asthma and atopy in sarcoidosis. Respirology. 2012;17(2):285–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lower EE, Malhotra A, Surdulescu V, Baughman RP. Armodafinil for sarcoidosis-associated fatigue: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(2):159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner GA, Lower EE, Corser BC, Gunther KL, Baughman RP. Sleep apnea in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1997;14(1):61–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bingol Z, Pihtili A, Gulbaran Z, Kiyan E. Relationship between parenchymal involvement and obstructive sleep apnea in subjects with sarcoidosis. Clin Respir J. 2015;9(1):14–21. doi: 10.1111/crj.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson KC, Huang F, Oldham JM, Bhardwaj N, Hogarth DK, Mokhlesi B. Excessive daytime sleepiness and obstructive sleep apnea in patients with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2013;143(6):1562–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosse-Henck A, Wirtz H, Hinz A. Subjective sleep quality in sarcoidosis. Sleep Med. 2015;16(5):570–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erb N, Cushley MJ, Kassimos DG, Shave RM, Kitas GD. An assessment of back pain and the prevalence of sacroiliitis in sarcoidosis. Chest. 2005;127(1):192–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahan A, Dunne A, Swartjes M, Proto PL, Heij L, Vogels O, van Velzen M, Sarton E, Niesters M, Tannemaat MR, Cerami A, Brines M. ARA 290 improves symptoms in patients with sarcoidosis-associated small nerve fiber loss and increases corneal nerve fiber density. Mol Med. 2013;19(1):334–45. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2013.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heij L, Niesters M, Swartjes M, Hoitsma E, Drent M, Dunne A, Grutters JC, Vogels O, Brines M, Cerami A, Dahan A. Safety and efficacy of ARA 290 in sarcoidosis patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: A randomized, double-blind pilot study. Mol Med. 2012;18(11):1430–6. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2012.00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamé IE, Weber WEJ. Catastrophising pain behaviour in sarcoidosis patients. Pain Clinic. 2005;17(4):351–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakkers M, Faber CG, Drent M, Hermans MCE, Van Nes SI, Lauria G, De Baets M, Merkies ISJ. Pain and autonomic dysfunction in patients with sarcoidosis and small fibre neuropathy. J Neurol. 2010;257(12):2086–90. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5664-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brines M, Swartjes M, Tannemaat MR, Dunne A, van Velzen M, Proto P, Hoitsma E, Petropoulos I, Chen X, Niesters M, Dahan A, Malik R, Cerami A. Corneal nerve quantification predicts the severity of symptoms in sarcoidosis patients with painful neuropathy. Technology. 2013 09/01; 2016/08;01(01):20–6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S2339547813500039 . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elfferich MD, Nelemans PJ, Ponds RW, De Vries J, Wijnen PA, Drent M. Everyday cognitive failure in sarcoidosis: The prevalence and the effect of anti-TNF-α treatment. Respiration. 2010;80(3):212–9. doi: 10.1159/000314225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Kleijn WPE, Drent M, Vermunt JK, Shigemitsu H, De Vries J. Types of fatigue in sarcoidosis patients. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(6):416–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elfferich MDP, De Fries J, Drent M. Type D or ‘distressed’ personality in sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2011;28(1):65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada Y, Tatsumi K, Yamaguchi T, Tanabe N, Takiguchi Y, Kuriyama T, Mikami R. Influence of stressful life events on the onset of sarcoidosis. Respirology. 2003 Jun;8(2):186–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drent M, Wirnsberger RM, Breteler MHM, Kock LMM, De Vries J, Wouters EFM. Quality of life and depressive symptoms in patients suffering from sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1998;15(1):59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Vries J, Drent M. Relationship between perceived stress and sarcoidosis in a dutch patient population. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2004;21(1):57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoitsma E, De Vries J, Van Santen-Hoeufft M, Faber CG, Drent M. Impact of pain in a dutch sarcoidosis patient population. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003;20(1):33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Drent M, Peros-Golubicic T. Psychometric qualities of the fatigue assessment scale in croatian sarcoidosis patients. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2005;22(2):133–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michielsen HJ, Drent M, Peros-Golubicic T, De Vries J. Fatigue is associated with quality of life in sarcoidosis patients. Chest. 2006;130(4):989–94. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michielsen HJ, Peros-Golubicic T, Drent M, De Vries J. Relationship between symptoms and quality of life in a sarcoidosis population. Respiration. 2007;74(4):401–5. doi: 10.1159/000092670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wijnen PA, Cremers JP, Nelemans PJ, Erckens RJ, Hoitsma E, Jansen TL, Bekers O, Drent M. Association of the TNF-α G-308A polymorphism with TNF-inhibitor response in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(6):1730–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00169413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bakkers M, Merkies ISJ, Lauria G, Devigili G, Penza P, Lombardi R, Hermans MCE, Van Nes SI, De Baets M, Faber CG. Intraepidermal nerve fiber density and its application in sarcoidosis. Neurology. 2009;73(14):1142–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bacf05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wirnsberger RM, De Vries J, Wouters EFM, Drent M. Clinical presentation of sarcoidosis in the netherlands. an epidemiological study. Neth J Med. 1998;53(2):53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(98)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Vries J, Drent M, Van Heck GL, Wouters EFM. Quality of life in sarcoidosis: A comparison between members of a patient organisation and a random sample. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1998;15(2):183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saligan LN. The relationship between physical activity, functional performance and fatigue in sarcoidosis. J Clin Nurs. 2014 Aug;23(15-16):2376–8. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karadall MN. Effects of inspiratory muscle training in subjects with sarcoidosis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Respir Care. 2016;61(4):483–94. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Kleijn WP, Drent M, De Vries J. Nature of fatigue moderates depressive symptoms and anxiety in sarcoidosis. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(2):439–52. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antoniou KM, Tzanakis N, Tzouvelekis A, Samiou M, Symvoulakis EK, Siafakas NM, Bouros D. Quality of life in patients with active sarcoidosis in greece. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;7(6):421–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hinz A, Brähler E, Möde R, Wirtz H, Bosse-Henck A. Anxiety and depression in sarcoidosis: The influence of age, gender, affected organs, concomitant diseases and dyspnea. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29(2):139–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holas P, Krejtz I, Urbankowski T, Skowyra A, Ludwiniak A, Domagala-Kulawik J. Anxiety, its relation to symptoms severity and anxiety sensitivity in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013;30(4):282–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spruit MA, Thomeer MJ, Gosselink R, Troosters T, Kasran A, Debrock A, Demedts MG, Decramer M. Skeletal muscle weakness in patients with sarcoidosis and its relationship with exercise intolerance and reduced health status. Thorax. 2005;60(1):32–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.022244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spruit MA, Thomeer MJ, Gosselink R, Wuyts WA, Van Herck E, Bouillon R, Demedts MG, Decramer M. Hypogonadism in male outpatients with sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2007;101(12):2502–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cox CE, Donohue JF, Brown CD, Kataria YP, Judson MA. The sarcoidosis health questionnaire: A new measure of health-related quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(3):323–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1343OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mihailović-Vucinic V, Ignjatović S, Dudvarski-Ilić A, Stjepanović M, Vuković M, Omčikus M, Singh S, Popević S, Videnović-Ivanov J, Filipović S. The role of vitamin D in multisystem sarcoidosis. J Med Biochem. 2012 2012/10;31(4):339–46. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanizawa K, Handa T, Nagai S, Oga T, Kubo T, Ito Y, Watanabe K, Aihara K, Chin K, Mishima M, Izumi T. Validation of the japanese version of the sarcoidosis health questionnaire: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beste C, Kneiphof J, Woitalla D. Effects of fatigue on cognitive control in neurosarcoidosis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(4):522–30. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Vries J, Michielsen H, Van Heck GL, Drent M. Measuring fatigue in sarcoidosis: The fatigue assessment scale (FAS) Br J Health Psychol. 2004;9(3):279–91. doi: 10.1348/1359107041557048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lower EE, Harman S, Baughman RP. Double-blind, randomized trial of dexmethylphenidate hydrochloride for the treatment of sarcoidosis-associated fatigue. Chest. 2008;133(5):1189–95. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wlrnsberger RM, De Vries J, Breteler MHM, Van Heck GL, Wouters EFM, Drent M. Evaluation of quality of life in sarcoidosis patients. Respir Med. 1998;92(5):750–6. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braam AWE, de Haan SN, Vorselaars ADM, Rijkers GT, Grutters JC, van den Elshout FJJ, Korenromp IHE. Influence of repeated maximal exercise testing on biomarkers and fatigue in sarcoidosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;33:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Rijswijk HNAJ, Vorselaars ADM, Ruven HJT, Keijsers RGM, Zanen P, Korenromp IHE, Grutters JC. Changes in disease activity, lung function and quality of life in patients with refractory sarcoidosis after anti-TNF treatment. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2013;1(6):437–43. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baughman RP, Sparkman BK, Lower EE. Six-minute walk test and health status assessment in sarcoidosis. Chest. 2007;132(1):207–13. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baughman RP, Judson MA, Lower EE, Highland K, Kwon S, Craft N, Engel PJ. Inhaled iloprost for sarcoidosis associated pulmonary hypertension. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2009;26(2):110–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Boer S, Wilsher ML. Validation of the sarcoidosis health questionnaire in a non-US population. Respirology. 2012;17(3):519–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Kleijn WPE, Elfferich MDP, De Vries J, Jonker GJ, Lower EE, Baughman RP, King TE, Jr, Drent M. Fatigue in sarcoidosis: American versus dutch patients. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2009;26(2):92–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Kleijn WPE, De Vries J, Wijnen PAHM, Drent M. Minimal (clinically) important differences for the fatigue assessment scale in sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2011;105(9):1388–95. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Vries J, Rothkrantz-Kos S, Van Dieijen-Visser MP, Drent M. The relationship between fatigue and clinical parameters in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2004;21(2):127–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Erckens RJ, Mostard RLM, Wijnen PAHM, Schouten JS, Drent M. Adalimumab successful in sarcoidosis patients with refractory chronic non-infectious uveitis. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250(5):713–20. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1844-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fleischer M, Hinz A, Brähler E, Wirtz H, Bosse-Henck A. Factors associated with fatigue in sarcoidosis. Respir Care. 2014;59(7):1086–94. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hinz A, Fleischer M, Brähler E, Wirtz H, Bosse-Henck A. Fatigue in patients with sarcoidosis, compared with the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(5):462–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jastrzębski D, Ziora D, Lubecki M, Zieleźnik K, Maksymiak M, Hanzel J, Początek A, Kolczyńska A, Nguyen Thi L, Żebrowska A, Kozielski J. Fatigue in sarcoidosis and exercise tolerance, dyspnea, and quality of life. 2015:31. doi: 10.1007/5584_2014_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalkanis A, Yucel RM, Judson MA. The internal consistency of PRO fatigue instruments in sarcoidosis: Superiority of the PFI over the fas. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013;30(1):60–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marcellis RGJ, Lenssen AF, Elfferich MDP, De Vries J, Kassim S, Foerster K, Drent M. Exercise capacity, muscle strength and fatigue in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(3):628–34. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00117710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marcellis RGJ, Lenssen AF, Kleynen S, De Vries J, Drent M. Exercise capacity, muscle strength, and fatigue in sarcoidosis: A follow-up study. Lung. 2013;191(3):247–56. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marcellis RGJ, Lenssen AF, Drent M, De Vries J. Association between physical functions and quality of life in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2014;31(2):117–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marcellis RGJ, Van Der Veeke MAF, Mesters I, Drent M, De Bie RA, De Vries GJ, Lenssen AF. Does physical training reduce fatigue in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2015;32(1):53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patel AS, Siegert RJ, Creamer D, Larkin G, Maher TM, Renzoni EA, Wells AU, Higginson IJ, Birring SS. The development and validation of the king’s sarcoidosis questionnaire for the assessment of health status. Thorax. 2013;68(1):57–65. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Strookappe B. Predictors of fatigue in sarcoidosis: The value of exercise testing. Respir Med. 2016;116:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Strookappe B, Elfferich M, Swigris J, Verschoof A, Verschakelen J, Knevel T, Drent M. Benefits of physical training in patients with idiopathic or end-stage sarcoidosis-related pulmonary fibrosis: A pilot study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2015;32(1):43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Strookappe B, Swigris J, De Vries J, Elfferich M, Knevel T, Drent M. Benefits of physical training in sarcoidosis. Lung. 2015;193(5):701–8. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gvozdenovic BS, Mihailovic-Vucinic V, Vukovic M, Lower EE, Baughman RP, Dudvarski-Ilic A, Zugic V, Popevic S, Videnovic-Ivanov J, Filipovic S, Stjepanovic M, Omcikus M. Effect of obesity on patient-reported outcomes in sarcoidosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(4):559–64. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baydur A, Alavy B, Nawathe A, Liu S, Louie S, Sharma OP. Fatigue and plasma cytokine concentrations at rest and during exercise in patients with sarcoidosis. Clin Respir J. 2011;5(3):156–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2010.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barros WGP, Neder JA, Pereira CAC, Nery LE. Clinical, radiographic and functional predictors of pulmonary gas exchange impairment at moderate exercise in patients with sarcoidosis. Respiration. 2004;71(4):367–73. doi: 10.1159/000079641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Judson MA, Silvestri J, Hartung C, Byars T, Cox CE. The effect of thalidomide on corticosteroid-dependent pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23(1):51–7. doi: 10.1007/s11083-006-9030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodrigues MM, Coletta ENAM, Ferreira RG, Pereira CAC. Delayed diagnosis of sarcoidosis is common in brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39(5):539–46. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132013000500003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rossman MD, Newman LS, Baughman RP, Teirstein A, Weinberger SE, Miller W, Jr, Sands BE. A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of infliximab in subjects with active pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23(3):201–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alhamad EH. The six-minute walk test in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Ann Thorac Med. 2009;4(2):60–4. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.49414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alhamad EH, Shaik SA, Idrees MM, Alanezi MO, Isnani AC. Outcome measures of the 6 minute walk test: Relationships with physiologic and computed tomography findings in patients with sarcoidosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alhamad EH, Idrees MM, Alanezi MO, Alboukai AA, Shaik SA. Sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: Clinical features and outcomes in arab patients. Ann Thorac Med. 2010;5(2):86–91. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.62471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kabitz H, Lang F, Walterspacher S, Sorichter S, Müller-Quernheim J, Windisch W. Impact of impaired inspiratory muscle strength on dyspnea and walking capacity in sarcoidosis. Chest. 2006;130(5):1496–502. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bourbonnais JM, Samavati L. Effect of gender on health related quality of life in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2010;27(2):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bourbonnais JM, Malaisamy S, Dalal BD, Samarakoon PC, Parikh SR, Samavati L. Distance saturation product predicts health-related quality of life among sarcoidosis patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kowalska A, Puścińska E, Goljan-Geremek A, Czerniawska J, Stokłosa A, Kram M, Tomkowski WZ, Górecka D. Six-minute walk test in sarcoidosis patients with cardiac involvement. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2012;80(5):430–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.De Boer S, Kolbe J, Wilsher ML. Comparison of the modified shuttle walk test and cardiopulmonary exercise test in sarcoidosis. Respirology. 2014;19(4):604–7. doi: 10.1111/resp.12276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Drake WP, Richmond BW, Oswald-Richter K, Yu C, Isom JM, Worrell JA, Shipley R, Bernard GR. Effects of broad-spectrum antimycobacterial therapy on chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013;30(3):201–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Baughman RP, Drent M, Kavuru M, Judson MA, Costabel U, Du Bois R, Albera C, Brutsche M, Davis G, Donohue JF, Müller-Quernheim J, Schlenker-Herceg R, Flavin S, Lo KH, Oemar B, Barnathan ES. Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(7):795–802. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-402OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sweiss NJ, Barnathan ES, Lo K, Judson MA, Baughman R. C-reactive protein predicts response to infliximab in patients with chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2010;27(1):49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baughman RP, Judson MA, Teirstein A, Yeager H, Rossman M, Knatterud GL, Thompson B. Presenting characteristics as predictors of duration of treatment in sarcoidosis. QJM Mon J Assoc Phys. 2006;99(5):307–15. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Baydur A, Alsalek M, Louie SG, Sharma OP. Respiratory muscle strength, lung function, and dyspnea in patients with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2001;120(1):102–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brill A, Ott SR, Geiser T. Effect and safety of mycophenolate mofetil in chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis: A retrospective study. Respiration. 2013;86(5):376–83. doi: 10.1159/000345596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Butler CR, Nouraei SAR, Mace AD, Khalil S, Sandhu SK, Sandhu GS. Endoscopic airway management of laryngeal sarcoidosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(3):251–5. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gibson GJ, Prescott RJ, Muers MF, Middleton WG, Mitchell DN, Connolly CK, Harrison BDW. British thoracic society sarcoidosis study: Effects of long-term corticosteroid, treatment. Thorax. 1996;51(3):238–47. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.3.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Judson MA, Baughman RP, Costabel U, Flavin S, Lo KH, Kavuru MS, Drent M, Culver DA, Davis GS, Fogarty CM, Hunninghake GW, Teirstein AS, Mandel M, McNally D, Tanoue L, Newman L, Wasfi Y, Patrick H, Rossman MD, Raghu G, Sharma O, Wilkes D, Yeager H, Donahue JF, Kaye M, Sweiss N, Vetter N, Thomeer M, Brutsche M, Nicod L, Valeyre D, Chanez P, Albera C, Grutters J, Hoogsteden H, Muller-Quernheim J, Bonnet R, Kanniess F. Efficacy of infliximab in extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: Results from a randomised trial. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(6):1189–96. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00051907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kallianos A, Zarogoulidis P, Ampatzoglou F, Trakada G, Gialafos E, Pitsiou G, Pataka A, Veletza L, Zarogoulidis K, Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Petridis D, Kioumi I, Rapti A. Reduction of exercise capacity in sarcoidosis in relation to disease severity. Patient Preference Adherence. 2015;9:1179–88. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S86465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Koutsokera A, Papaioannou AI, Malli F, Kiropoulos TS, Katsabeki A, Kerenidi T, Gourgoulianis KI, Daniil ZD. Systemic oxidative stress in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009;22(6):603–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lopes AJ, Menezes SLS, Dias CM, Oliveira JF, Mainenti MRM, Guimarães FS. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing variables as predictors of long-term outcome in thoracic sarcoidosis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2012;45(3):256–63. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Muers MF, Middleton WG, Gibson GJ, Prescott RJ, Mitchell DN, Connolly CK, Harrison BDW. A simple radiographic scoring method for monitoring pulmonary sarcoidosis: Relations between radiographic scores, dyspnoea grade and respiratory function in the british thoracic society study of long-term corticosteroid treatment. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1997;14(1):46–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Park MK, Fontana JR, Babaali H, Gilbert-McClain LI, Stylianou M, Joo J, Moss J, Manganiello VC. Steroid-sparing effects of pentoxifylline in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2009;26(2):121–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rabin DL, Thompson B, Brown KM, Judson MA, Huang X, Lackland DT, Knatterud GL, Yeager H, Jr, Rose C, Steimel J, Baughman RP, Bresnitz EA, Cherniak R, Depablo L, Hunninghake G, Iannuzzi MC, Johns CJ, McLennan G, Moller DR, Musson R, Newman LS, Rossman MD, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS, Terrin ML, Winberger SE. Sarcoidosis: Social predictors of severity at presentation. Eur Respir J. 2004;24(4):601–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00070503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Utz JP, Limper AH, Kalra S, Specks U, Scott JP, Vuk-Pavlovic Z, Schroeder DR. Etanercept for the treatment of stage II and III progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis. Chest. 2003;124(1):177–85. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wallaert B, Talleu C, Wemeau-Stervinou L, Duhamel A, Robin S, Aguilaniu B. Reduction of maximal oxygen uptake in sarcoidosis: Relationship with disease severity. Respiration. 2011;82(6):501–8. doi: 10.1159/000330050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Barnett CF, Bonura EJ, Nathan SD, Ahmad S, Shlobin OA, Osei K, Zaiman AL, Hassoun PM, Moller DR, Barnett SD, Girgis RE. Treatment of sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: A two-center experience. Chest. 2009;135(6):1455–61. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wyser CP, Van Schalkwyk EM, Alheit B, Bardin PG, Joubert JR. Treatment of progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis with cyclosporin A: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(5):1371–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.5.9506031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Brancaleone P, Perez T, Robin S, Neviere R, Wallaert B. Clinical impact of inspiratory muscle impairment in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2004;21(3):219–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chang JA, Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Raghu G. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with interstitial lung disease. Chest. 1999;116(5):1175–82. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.5.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Alilović M, Peros-Golubicić T, Radosević-Vidacek B, Koscec A, Tekavec-Trkanjec J, Solak M, Hećimović A, Smojver-Jezek S. WHOQOL-bREF questionnaire as a measure of quality of life in sarcoidosis. Coll Antropol. 2013;37(3):701–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.De Vries J, Van Heck GL, Drent M. Gender differences in sarcoidosis: Symptoms, quality of life, and medical consumption. Women Health. 2000;30(2):99–114. doi: 10.1300/j013v30n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wirnsberger RM, De Vries J, Jansen TLTA, Van Heck GL, Wouters EFM, Drent M. Impairment of quality of life: Rheumatoid arthritis versus sarcoidosis. Neth J Med. 1999;54(3):86–95. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(98)00148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rosenbach M, Yeung H, Chu EY, Kim EJ, Payne AS, Takeshita J, Vittorio CC, Wanat KA, Werth VP, Gelfand JM. Reliability and convergent validity of the cutaneous sarcoidosis activity and morphology instrument for assessing cutaneous sarcoidosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(5):550–6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Olsen HH, Muratov V, Cederlund K, Lundahl J, Eklund A, Grunewald J. Therapeutic granulocyte and monocyte apheresis (GMA) for treatment refractory sarcoidosis: A pilot study of clinical effects and possible mechanisms of action. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;177(3):712–9. doi: 10.1111/cei.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pariser RJ, Paul J, Hirano S, Torosky C, Smith M. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adalimumab in the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(5):765–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Saligan LN, Levy-Clarke G, Wu T, Faia LJ, Wroblewski K, Yeh S, Nussenblatt RB, Sen HN. Quality of life in sarcoidosis: Comparing the impact of ocular and non-ocular involvement of the disease. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17(4):217–24. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2010.483754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Goracci A, Fagiolini A, Martinucci M, Calossi S, Rossi S, Santomauro T, Mazzi A, Penza F, Fossi A, Bargagli E, Pieroni MG, Rottoli P, Castrogiovanni P. Quality of life, anxiety and depression in sarcoidosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):441–5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Judson MA, Chaudhry H, Louis A, Lee K, Yucel R. The effect of corticosteroids on quality of life in a sarcoidosis clinic: The results of a propensity analysis. Respir Med. 2015;109(4):526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Judson MA, Mack M, Beaumont JL, Watt R, Barnathan ES, Victorson DE. Validation and important differences for the sarcoidosis assessment tool: A new patient-reported outcome measure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(7):786–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1785OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Du Bois RM, Greenhalgh PM, Southcott AM, Johnson NM, Harris TAJ. Randomized trial of inhaled fluticasone propionate in chronic stable pulmonary sarcoidosis: A pilot study. Eur Respir J 1999. 1999;13(6):1345–50. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13613519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Milman N, Svendsen CB, Hoffmann AL. Health-related quality of life in adult survivors of childhood sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2009;103(6):913–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Milman N, Graudal N, Loft A, Mortensen J, Larsen J, Baslund B. Effect of the TNF-α inhibitor adalimumab in patients with recalcitrant sarcoidosis: A prospective observational study using FDG-PET. Clin Respir J. 2012;6(4):238–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2011.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dudvarski-Ilić A, Mihailović-Vucinić V, Gvozdenović B, Zugić V, Milenković B, Ilić V. Health related quality of life regarding to gender in sarcoidosis. Coll Antropol. 2009;33(3):837–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wirnsberger RM, Drent M, Hekelaar N, Breteler MHM, Drent S, Wouters EFM, Dekhuijzen PNR. Relationship between respiratory muscle function and quality of life in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 1997;10(7):1450–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10071450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mihailovic-Vucinic V, Gvozdenovic B, Stjepanovic M, Vukovic M, Markovic-Denic L, Milovanovic A, Videnovic-Ivanov J, Zugic V, Skodric-Trifunovic V, Filipovic S, Omcikus M. Administering the sarcoidosis health questionnaire to sarcoidosis patients in serbia. J Bras Pneumol. 2016 Apr;42(2):99–105. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37562015000000063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Choi J, Hoffman LA, Sethi JM, Zullo TG, Gibson KF. Multiple flow rates measurement of exhaled nitric oxide in patients with sarcoidosis: A pilot feasibility study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2009;26(2):98–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.de Kleijn WP, De Vries J, Lower EE, Elfferich MD, Baughman RP, Drent M. Fatigue in sarcoidosis: A systematic review. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009 Sep;15(5):499–506. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32832d0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL. Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The fatigue assessment scale. J Psychosom Res. 2003 Apr;54(4):345–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995 Apr;39(3):315–25. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hagelin CLC. The psychometric properties of the swedish multidimensional fatigue inventory MFI-20 in four different populations. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(1):97–104. doi: 10.1080/02841860601009430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fletcher CM, Elmes PC, Fairbairn AS, Wood CH. The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population. Br Med J. 1959 Aug 29;2(5147):257–66. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5147.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the medical research council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999 Jul;54(7):581–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Crisafulli E, Clini EM. Measures of dyspnea in pulmonary rehabilitation. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2010 Jun 30;5(3):202–10. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-5-3-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Stenton C. The MRC breathlessness scale. Occup Med (Lond) 2008 May;58(3):226–7. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqm162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mahler DA, Weinberg DH, Wells CK, Feinstein AR. The measurement of dyspnea. contents, interobserver agreement, and physiologic correlates of two new clinical indexes. Chest. 1984 Jun;85(6):751–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.85.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.De Vries J, Drent M. Quality of life and health-related quality of life measures. Respir Med. 2001 Feb;95(2):159–60. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.The world health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(12):1569–85. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Den Oudsten BL, Zijlstra WP, De Vries J. The minimal clinical important difference in the world health organization quality of life instrument--100. Support Care Cancer. 2013 May;21(5):1295–301. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Development of the world health organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. the WHOQOL group. Psychol Med. 1998 May;28(3):551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992 Jun;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kosinski M, Zhao SZ, Dedhiya S, Osterhaus JT, Ware JE., Jr Determining minimally important changes in generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Jul;43(7):1478–87. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200007)43:7<1478::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. the st. george’s respiratory questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992 Jun;145(6):1321–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Yeager H, Rossman MD, Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, Rabin DL, Iannuzzi MC, Rose C, Bresnitz EA, DePalo L, Hunninghake G, Johns CJ, McLennan G, Moller DR, Newman LS, Rybicki B, Weinberger SE, Wilkins PC, Cherniack R. Pulmonary and psychosocial findings at enrollment in the ACCESS study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2005;22(2):147–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977 June 01;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961 Jun;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kendall PC, Hollon SD, Beck AT, Hammen CL, Ingram RE. Issues and recommendations regarding use of the beck depression inventory [Google Scholar]

- 150.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983 Jun;67(6):361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002 Feb;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Hoitsma E, Marziniak M, Faber CG, Reulen JP, Sommer C, De Baets M, Drent M. Small fibre neuropathy in sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2002 Jun 15;359(9323):2085–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08912-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Lauria G, Hsieh ST, Johansson O, Kennedy WR, Leger JM, Mellgren SI, Nolano M, Merkies IS, Polydefkis M, Smith AG, Sommer C, Valls-Sole J. European Federation of Neurological Societies, Peripheral Nerve Society. European federation of neurological societies/peripheral nerve society guideline on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. report of a joint task force of the european federation of neurological societies and the peripheral nerve society. Eur J Neurol. 2010 Jul;17(7,903,12):e44–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Hoitsma E, De Vries J, Drent M. The small fiber neuropathy screening list: Construction and cross-validation in sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2011;105(1):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Chervin RD. Sleepiness, fatigue, tiredness, and lack of energy in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2000 Aug;118(2):372–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991 Dec;14(6):540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]