Abstract

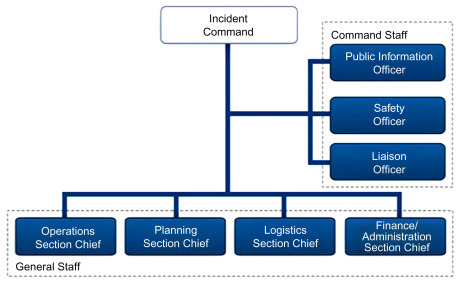

Airport Emergency Planning, Part II provides an overview of the core functions within airport emergency management, which include command, control, and communications (C3) and law enforcement, firefighting, public notification, emergency medical response, and resource management. Many airport emergencies require public notifications and, in some cases, Protective Actions, such as evacuation and shelter-in-place. Police, fire, and other Emergency Medical Services (EMS) comprise the core first responders to nearly any emergency, and these personnel have numerous responsibilities throughout the Airport Emergency Plan (AEP). The National Incident Management System, created after 9/11, is the standard method of managing disasters, incidents, and other events in the United States. It is based on three principles: Incident Command System (ICS), Multi-Agency Coordination, and Public Information. The five functions of ICS are command, operations, planning, logistics, and finance/administration. For some incidents, an intelligence/investigative function is added.

Keywords: Command, Control, and Communications (C3); Airport Emergency Alert Notification and Warning; Airport Emergency Public Information; Emergency Protective Actions; Airport Emergency Operations Center (EOC); Airport Incident Command Post (ICP); Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service (RACES); Radio Emergency Associate Communications Team (REACT); Emergency Shelter-in-Place; Disaster Medical Assistant Teams (DMATs); Multi-Agency Coordination System (MACS); Sensitive Security Information (SSI); Incident Command System (ICS)

Airport communications control center Aspen-Pitkin County Regional Airport, CO.

Image by Shahn Sederberg, courtesy Colorado Division of Aeronautics, 2013.

Loading fire retardant on a Conair fire tanker at the U.S. Forest Service tanker base located at Rocky Mountain Metropolitan Airport, CO.

Image by Shahn Sederberg, courtesy Colorado Division of Aeronautics, 2012.

Airport Operations security team.

Courtesy Denver International Airport, CO [date unknown].

In revising Advisory Circular (AC) 150/5200-31C, Airport Emergency Plan, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) separated functional areas from the hazard-specific sections (FAA, 2010). This separation has created some confusion and more than a few redundancies in the AC. The Functional Section of the Airport Emergency Plan (AEP) is best understood by applying the term function literally, rather than connecting the function to a specific agency. The Functional Section addresses the functions that must be addressed in virtually any emergency, regardless of which individual or agency performs the function. According to the FAA (2010, pp. 37–38) the core functions of an aviation emergency are:

-

1.

Command and control;

-

2.

Communications;

-

3.

Alert Notification and Warning;

-

4.

Emergency Public Information;

-

5.

Protective Actions;

-

6.

Law enforcement/security;

-

7.

Firefighting and rescue;

-

8.

Health and medical;

-

9.

Resource management; and

-

10.

Airport Operations and maintenance.

Although not addressed in the AEP, other functions include: damage assessment, Search and Rescue, incident mitigation and recovery, mass care, and chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosive (CBRNE) protection (FAA, 2010, p. 37). Airport operators may wish to address security-related functions more thoroughly in the Airport Security Program (ASP) to protect the sensitive nature of that information.

As in all areas of Airport Operations and emergency management, the resources and staff on hand determine whether on- or off-airport responders, or some mix thereof, will handle these functions. Large, commercial service airports often have enough on-airport personnel, with the expertise and equipment to handle most or all of the core functions, at least for the initial response phase. Small, commercial service airports may have to rely heavily on off-airport personnel, through the use of Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs), and with their own personnel assuming multiple duties. Many Airport Operations and maintenance personnel at small airports are trained in Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF), and some in Basic Medical Care or as Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs).

Essential Functions for Emergency Operations

The AC on airport emergency planning provides instructions to an airport operator on what should be included in the AEP. Each of the functional areas follows a format of: Purpose, Situation and Assumptions, Operations; Organization and Assignment of Responsibilities; Administration and Logistics; Plan Development and Maintenance; and Reference and Authorities. In this way, it is similar to the Basic Plan. In all the functional areas, sections relating to the Plan Development and Maintenance and Reference and Authorities generally note that the section should identify the responsible parties for keeping this section of the AEP up-to-date and that any references used in building the Functional Section should be noted in the AEP.

While each element of the Functional Sections includes Situations and Assumptions, there are several core situations and assumptions that are related to most every incident. First, it must be recognized that not all emergency situations can be anticipated. Joseph Pfeifer, Chief of Counterterrorism and Emergency Preparedness, Fire Department of New York (FDNY), notes that by its very nature, a crisis is often random, unexpected, and novel, requiring leaders to be prepared for a wide variety of urgent circumstances that demand quick decisions (Pfeifer, 2013, p. 2).

Decisions by leaders in an extreme event can also be challenged by the nature of the event, whether it is a routine emergency, or an extreme emergency, falling outside the parameters of what a police officer, firefighter, or Airport Operations officer is accustomed to seeing. Pfeifer classifies three types of extreme events: routine, crisis, and catastrophe. Routine emergencies use a single Incident Commander (IC) and have hierarchical command and control. One person is in charge and gives orders. In a crisis, which requires a multiagency response, the hierarchal structure divides into several leaders, each overseeing their own network, reporting to a central IC. If the incident becomes catastrophic, a formation of random networks haphazardly connected with no one central leader controlling the entire incident may form (Pfeifer, 2013, p. 9). It is important for both first responders and policy makers to understand that there will be an element of randomness and that not every situation can be controlled at all times.

Airport emergency management operates on a standard set of assumptions: first, hazards and incidents occur at airports, and for large-scale events outside assistance will likely be needed. Some incidents will have a long duration, several days or even weeks; unforeseen events will occur and the airport must still generate a response. Also, all personnel with responsibilities under the AEP should be knowledgeable and trained in their expected actions to be performed during an actual emergency and ensure that the materials and equipment necessary for the performance of those duties are available and in working order.

Although not typically noted in many AEPs, a realistic assumption should be that not all personnel will be available to respond to an emergency when it occurs, because of variations in staffing levels that occur throughout the day, week, and year. A well-written AEP should account for these variations and have other contingencies and alternate courses of action available. For long-duration incidents, personnel will have to rotate in and out of the command structure and will require relief, refreshment, and rest.

Command and Control

Command and control is the largest of the Functional Sections, as it addresses many elements of managing an emergency incident and how the National Incident Management System (NIMS) integrates into the airport domain. Homeland Security Presidential Directive-5, Management of Domestic Incidents, directed the creation of the NIMS, which provides a template for federal, state, tribal, and local governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as the American Red Cross, and private sector organizations to work together to prevent, prepare, respond to, and recover from emergency incidents (FEMA, 2008b).

The FAA argues that Command and Control is the most critical element of the emergency management function (FAA, 2010). The purpose of Command and Control is to provide the overall command structure, including a line of succession, and to establish the relationship between the Emergency Operations Center (EOC), which is focused on overall centralized command and control, and the Incident Command Post (ICP) 1 , which is focused on on-scene command and control. Relationships to outside agencies, such as state, regional, or local emergency management agencies or government structures, may also be part of the overall command structure and should be addressed in the AEP.

While the NIMS is supposed to be integrated into airport emergency management functions, aviation is rather unique compared to its transportation counterparts. In many incidents outside the aviation domain, such as in the local community, a standard, on-scene, single IC system is used, supported by emergency dispatchers and without the involvement of the local or regional EOC. The EOC is only activated for large-scale events when the on-scene assets are overwhelmed or when larger portions of the community are involved.

Many airports, however, have EOCs and communications and dispatch centers onsite. The EOCs get activated for most airport emergencies, and even some nonemergencies, such as snow removal, or for special events. Since an airport EOC is at the airport where most of the airport incidents occur, it is physically closer to the actual incident, and it is not unusual for the IC to be located in the EOC, using CCTV (closed circuit television) cameras or eyes on the incident (literally looking out the window of the EOC to the incident on the airfield) to direct and control operations. This model challenges a longstanding principle that the IC is always literally on-scene and thus in the best position to make decisions about how to manage the incident. While many airport operators easily make the distinction, off-airport personnel, mutual aid agencies, and those newly assigned to the airport that have come from other, more traditional command structures may have some adjustments to make. Frequent exercises and training with off-airport personnel can help them better acclimate to the aviation structure, as airports bounce back and forth between IC on-scene and IC in the EOC structures. Airports have been known to use a blended structure, with the IC on-scene, and an EOC commander in the EOC. To avoid confusion, the EOC commander should be designated as a Deputy IC.

For a large-scale incident, the IC is almost always, initially, on-scene. Incident Command is established by the first responder on-scene until relieved by either a superior officer from the first responder’s own organization or the first responding entity that has responsibility over the incident according to the line of succession. For example, Airport Operations officers are commonly first on-scene for an aircraft incident as they are typically in the airfield conducting their continuous self-inspections and other airfield related duties. Upon arrival at the incident scene, the Airport Operations officer will assume Incident Command and broadcast such over the airport’s communication system. Regardless of the experience level of the first arriving officer or individual in the line of succession, that individual is in command until properly relieved. If the line of succession said that the first in command is airport fire, followed by airport police, then either the firefighting agency or the police department will take over Incident Command from the Airport Operations officer upon their arrival.

It is important to note that “in command” does not necessarily mean in an operating capacity to alleviate the problem. No one expects an Airport Operations officer, without the proper equipment and training, to run into the burning fuselage of an airplane. If an Airport Operations officer does not have firefighting responsibilities, training, or equipment, then their command function is to establish themselves as the IC (for now), set up an Incident Command Post, and ensure responding agencies are notified to the location of the incident and advised on accessible routes, if possible. The IC then ensures overall scene safety and security to the extent possible. Additionally, in some instances, such as an active shooter, any unarmed individual, including Airport Operations personnel, are usually advised to avoid the area entirely, to run away, or seek shelter, if necessary, until the shooter is neutralized. As additional units arrive, the Airport Operations person may retain IC duties, or IC duties may switch to then-appropriate personnel, based on the incident type, such as having ARFF personnel as Incident Command for an airplane crash, whereas airport police would serve as initial Incident Command for a sabotage, hijack, or bomb threat incident.

All those having command responsibilities under the AEP are listed in the Command and Control2 section, along with key supporting agencies. The core responsibilities of each organization are:

-

1.

Chief Executive/Airport Manager: Activates the EOC and provides overall direction of response and recovery operations, designating an IC as appropriate.

-

2.

ARFF: Responds to the scene, establishes an ICP, and performs Incident Command duties as necessary. Conducts firefighting operations, handles hazardous materials, scene safety, and evacuation.

-

3.

Law Enforcement: Responds to incidents and provides law enforcement services, including scene security, traffic control, and assists with evacuation. For security-related incidents, acts as the Incident Command, establishing an ICP and assigning personnel, as appropriate.

-

4.

Public Works: Responds to incidents, as appropriate, directs public work operations, including debris collection and removal, provides damage assessments, as related to damage to public utilities, and provides emergency power generators with fuel, emergency lighting, and sanitation to emergency responders.

-

5.

Public Information Officer: In addition to reporting to the EOC if necessary, handles all media functions.

-

6.

Health and Medical Coordinator: Sends a representative to the EOC, if required, coordinates health and medical assistance, and provides critical stress-management counseling.

-

7.

Communications Coordinator: Supports communication operations of the EOC.

-

8.

Animal Care and Control Agency: May be required to send a representative to the EOC and is responsible for the rescuing and capture of animals that have escaped from confinement on the aircraft, providing care for injured, sick, and stray animals, and disposal of deceased animals.

The local coroner’s office, National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the American Red Cross are also often included in the command and control section. Command and control and the NIMS are addressed later in the Command and Control and NIMS sections.

Communications

Communication is a critical element in the ability to command resources and manage an incident. In addition to the day-to-day communications necessary to operate the airport, including police, fire, and emergency medical service (EMS) dispatch, maintenance and Airport Operations personnel, and air traffic control (ATC), any large-scale emergency operation will require communications beyond the normal capacities and equipment of a typical airport (FAA, 2010, p. 50). During an incident, Airport Operations personnel should assume that noise levels will be higher than normal, both on the airfield and in the terminal building; there may be areas on the airport where radios or cell phone coverage is sporadic or nonexistent; and during the emergency, communications equipment will be used for longer than the usual number of hours, resulting in the need for additional backup equipment and a ready supply of batteries. Reliability and interoperability are critical to the communications function. Reliability is the ability of the communications network or equipment to function when needed. Interoperability allows emergency management personnel to communicate across agencies through phone, text, email, video, or other means.

The Airport Manager must ensure that adequate communications systems are in place for normal and emergency operations. In extraordinary circumstances, such as a wide-scale community disaster, some organizations such as the Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service (RACES) and the Radio Emergency Associate Communications Team (REACT) may be available to support emergency communications.

The Communications Center Coordinator ensures all necessary communications systems are available with proper redundancy, interoperability, and backups, where necessary. The coordinator also must support media communications and ensure the communications station in the EOC is properly staffed and able to function at full capacity.

An effective communications system should include recording devices with time/date capability, a sufficient number of landlines with both listed and unlisted numbers, and extra cell phones and batteries. Runners should also be assigned to the EOC and the Mobile Command Unit to augment other modes of communication (NFPA, 2013). During a power outage and resulting communications failure, runners are invaluable, as they are often the only means to communicate essential information.

Communications center personnel are also tasked with maintaining a chronological log of events and keeping the IC and other personnel apprised of events and activities related to the incident. AEPs often identify specific communications systems and frequencies to be used and by which agencies, including special radio codes such as discrete codes to notify all those on a frequency of an airplane crash, hijacking, bomb threat, or other incident that should not be broadcast in the clear on unsecure frequencies. All other agencies with emergency management responsibilities under the AEP must keep their communications equipment up-to-date and in working order, and the agencies must report to airport management any changes in procedures or personnel.

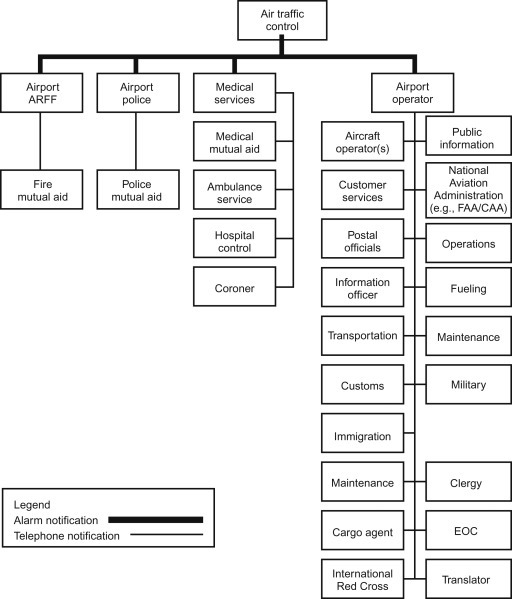

A core operating principle in the communications function is the ability for response agencies to be notified when there is an aircraft or other airport emergency. The emergency communications system explains how personnel are notified of an airplane or airport emergency, along with daily testing requirements of alarm equipment. Most notifications of an airplane emergency come first to the air traffic control tower (ATCT), which then activates a crash phone or similar alert system, to notify airport fire and operations personnel (Figure 11.1 ). However, the ATCT is not always aware an Aircraft Accident has occurred, and other situations necessitate a callout of fire, police, and other response personnel, so the notification system must address when an agency other than the ATCT becomes aware of an incident and how each agency will activate the crash alarm or emergency response process. Usually this is a call to Airport Operations, which can then activate the crash phone or alert system. According to the NFPA (2013), the following agencies should be immediately notified by alarm of an aircraft emergency: airport ARFF, airport police, medical service providers, and the airport operator. Additional agencies should be notified via telephone, or automated notification system, as needed.

Figure 11.1.

Sample incident notification chart.

Source: NFPA, 2013.

Airport Operations personnel, in consultation with the Fire Chief, ATC, and sometimes the pilot, often determine the level of alert status. These functions cross over into the next functional area, Alert Notification and Warning.

Alert Notification and Warning

During an emergency, airport management must have a system in place to alert the public and to advise them on the actions to take, and also to alert first responders that an incident to which they should respond has occurred. Usually it is the job of the Communications Section to notify response agencies, tenants, and the public of any incidents or threats to the airport and to notify the public agencies, usually through the Public Information Officer (PIO), of what actions to take.

Airport operators must identify in their AEP methods and procedures to notify emergency response personnel and the airport population, including passengers, visitors, vendors, contractors, and tenants. Notifications to personnel on the airfield, particularly of inclement weather, such as tornadoes and lightning, are important and can be challenging because of the high noise levels on the airfield. Tornado sirens may not be heard over the noise of aircraft engines as planes start up, taxi, takeoff, and land. Some airports initiate a ringdown to their major tenants, who can then use their agency radios, or personnel, to communicate to those working in the Air Operations Area (AOA) of a hazard and of the appropriate actions to take.

Inside the terminal, announcements compete for the public’s attention; visitors to the airport are bombarded by gate announcements, paging announcements, and the endless warnings not to leave a bag unattended and to report suspicious persons to airport police. Airport management personnel must be aware that many passengers ignore announcements, requiring messages to be repeated, often several times, before the message begins to “sink in” (FAA, 2010, p. 54). Also, some passengers may have functional needs or may be unable to hear or understand the language. Airports can use a warning tone, similar to the FEMA Emergency Broadcast System tones used on local TVs, to capture the public’s attention, along with Visual Paging systems. Airports with Ambassador programs have the ability to notify their Ambassadors, who can spread the word.

Airport paging systems should also have the ability to override any other public address systems in case of emergency. Elderly passengers, as well as some with functional needs, must be advised of evacuation routes or routes to shelter that are accessible by individuals with difficulty accessing stairs or escalators.

Emergency response personnel must also be notified during an airport incident or natural disaster. If the crash occurred at an airport with a control tower or an ARFF station, a ringdown line is used to notify the first responders. At the crudest level, notifications of emergency response personnel can be done through a notification list and a telephone. It is essential that the telephone list is always kept up-to-date, listing the primary point of contact, alternate point of contact, accurate phone numbers and emails, and whether the point of contact’s phone can receive text messages. Most large- and medium-size airports have adopted automated notification and messaging systems, which can provide situational information to personnel via their phone or tablet. Similar to text alerts that individuals receive on their cell phones from The Weather Channel and other apps about the status and location of severe weather, automated notification systems provide a variety of services to an airport operator (Everbridge, 2015), including:

-

1.

Automatic messaging during severe weather;

-

2.

The ability to send messages in multiple formats and to multiple platforms (phone, tablet, text, etc.);

-

3.

Immediate mass population notification allowing all response personnel to receive the information simultaneously, rather than when they are reached on the callout or phone-tree list;

-

4.

Geographic information system (GIS) mapping noting the precise location of the incident or weather event;

-

5.

Secure communications;

-

6.

Verification of receipt of message.

Critical communications software reduces human error by ensuring the message that goes out is the same message to all parties and that the message has not been interpreted or paraphrased (Everbridge, 2015). Not only is uniformity of messaging important for incident response, but it also helps to defend legal claims after the fact.

The Airport Manager must also draft contingency plans to provide an alert and warning if the established communications systems fail to work, which can occur during natural disasters with the power grid offline and cell towers out of service. Backup plans usually include direct communication to Airport Operations, police, and maintenance personnel, who spread the word verbally. Transportation Security Administration (TSA) Transportation Security Officer personnel can also be extremely helpful in this capacity as all passenger traffic filters through the checkpoints and exit lanes.

Although the AEP AC does not specify a role for the Communications Center Coordinator under the Alert Notification and Warning section, it is usually communications center personnel who are directly responsible for carrying out the alert and notification functions. The Communications Center Coordinator should ensure that call lists and/or critical communications software are up-to-date and that all personnel know the conditions for activating various warnings and alerts.

Any other agencies with AEP responsibilities notify volunteers and other employees who may be part of a Community Emergency Response Team (CERT)3 team or other internal response team to report to their duty stations and, if appropriate, send home nonessential personnel (or order to shelter-in-place) or recall essential personnel and determine whether to suspend normal business operations.

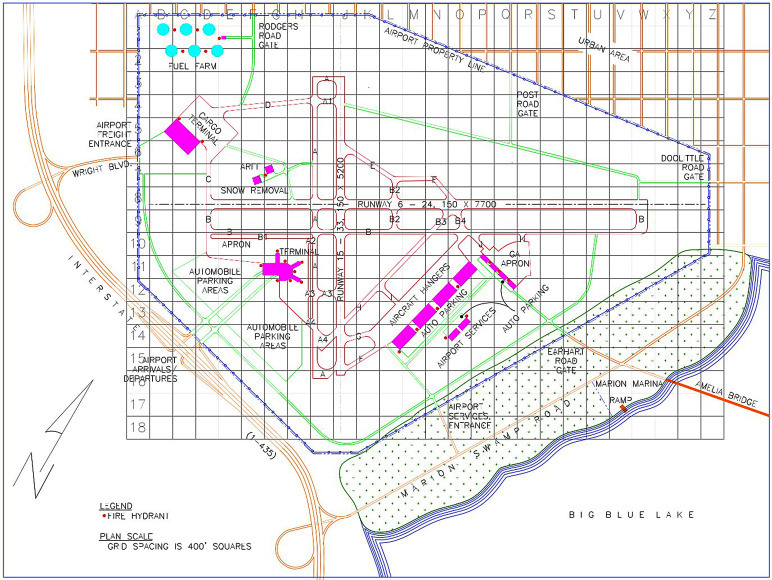

Airport grid maps should also be developed and used by all response personnel (Figure 11.2 ). Grid maps are helpful for on-airport responders who may have a difficult time deciphering airport-related signs and markings during an emergency, but are essential for off-airport responders. To provide an example, during an emergency, most off-airport (and some on-airport) responders would not know where the intersection of Charlie Four and Runway Three-Five Right is, but they can all look at a grid map and figure out where “B-4” is.

Figure 11.2.

Sample airport grid map.

Source: FAA, 2010, p. 278.

Emergency Public Notification

The Emergency Public Information section within the AEP AC has crossover with the Alert Notification and Warning and the Communications Sections, but more specifically addresses notifications to the community outside of the airport. The AEP must describe the methods used by the airport to notify the community at-large of an issue, emergency, or situation occurring at the airport that could affect the community or the operation of the airport. For most emergencies, the Emergency Public Information (EPI) organization (within the airport, it is usually the communications center) will initially focus on the dissemination of information to the public who are at-risk on the airport property (FAA, 2010), then to those outside its borders.

Prior to the advent of social media, the only means of addressing the public was through the mass communications abilities of the media. Social media now allows the airport to directly communicate with the populace, but social media also allows everyone else a community, or even worldwide, audience. This can cause confusion as passengers and others involved in or witnessing an event at the airport tweet, text, email, and post YouTube clips (often without context) of what they are seeing. During the November 1st active shooter event at LAX (Los Angeles International Airport), TSA personnel evacuating Terminal 3, where the shootings were occurring, texted coworkers in Terminals 1 and 2, causing both terminals to self-evacuate (when TSA shut down the checkpoint and ran, everyone followed). Many personnel evacuated to the ramp area where aircraft operations were taking place.

The airport operator must establish the lines of communication to be used in an emergency, listing the pathways, the organizations to be contacted, and specific means of contacting, along with contact information, hours of operation for radio/TV/cable stations, circulation (morning/evening, daily/weekly) of newspapers, and languages covered. Alternative methods should also be addressed if the primary pathways are unavailable (vehicle-mounted public address, door-to-door, etc.). The media generally cooperates with the airport’s public notification process, and the media will be interested because of the nature of the story; however, the media can be fickle and may not transmit the information in the same way it was received from the airport and may not transmit it for long. Plus, during a natural disaster, dozens of response agencies and communities will attempt to use the media to push out information, and airport operators may find themselves competing for attention. Notifying landside operations personnel, others picking up and dropping off passengers, and those in the parking garage or outlying parking lots must also be addressed.

Many emergency public notifications relate to the status of the airport, particularly during inclement weather, such as snow and severe thunderstorms, and are fairly routine. Individuals want to know about flight delays, whether the airport is open or closed, and for how long. In the event of a plane crash, family members and friends of passengers want to know where to go for more information and assistance, while others want to know the status of the airport and whether their flight is affected.

For a mass weather event, such as a pending hurricane, along with associated flooding, tornadoes, and high winds, airports should have scripted messages noting the specific hazard; the estimated area and time of incident; priority protection measures (sandbagging, relocating aircraft, securing equipment); recommended content of disaster supply kits; evacuation instructions (coordinate with local emergency management); other “do’s and don’ts”; and telephone or social media identifying information for specific kinds of inquiry. Other scripts can be prepared and given to airport paging or communications center personnel to be used depending on the emergency, such as what to do after an accident or natural disaster, whom to connect with for more information, and support for individuals that have loved ones who may have been involved in a plane crash. Part of the Emergency Public Notification process should be the simulation and practice of setting up the Joint Information Center, media center, and family assistance centers.

EPI should also be coordinated between the local government and the airport or other agencies, which rely on the same media sources. State laws often apply to how local and state agencies handle EPI, and there may be situations in which the federal government also becomes involved.

The Airport Director approves the release of information to the public, oftentimes working with the PIO, who consequently works with PIOs from other agencies, air carriers, tenants, and off-airport agencies. PIOs schedule news conferences, issue press releases, supervise the media center, and do their best to handle “rumor control.” If available, voluntary organizations can staff phone lines and disseminate information to the public. Both during and after the incident, PIO staff will collect press clips and stories about the airport, assess the public’s reaction, chase down false reports, and provide summaries to the Command Staff.

Protective Actions

Protective Actions are generally focused on protecting the health and safety of passengers and airport employees. The Airport Director must ensure that there is a policy on evacuation, along with policies on how to handle individuals who do not comply with evacuation or shelter-in-place orders. Primary methods of notification within an airport terminal typically include the fire alarm system and the public address or public announcement system. Airport police, fire, operations, and maintenance personnel are the primary individuals who facilitate evacuations or shelter-in-place actions.

Protective action plans typically focus on one of two options, shelter-in-place or evacuation. Evacuation plans and maps should be developed, along with routes and signs put into place throughout the airport. Airport and airline offices should also have evacuation plans with designated rally points outside of the structure. In some evacuations, personnel are simply looking to get away from the airport, such as for incoming natural disasters. However, for bomb threats, active shooter, or an actual detonation of an improvised explosive device, a designated rally point for personnel from each office or floor of an office building or personnel working in the terminal building, along with an appointed floor security manager who has a roster of personnel who are in the office that day, can help identify if individuals in the building are still in need of assistance.

For short-term incidents, such as severe thunderstorms or tornadoes, the shelter-in-place is typically the better option. In some cases, like tornadoes, evacuation may actually be more dangerous than staying inside the terminal building. Many airports, even small facilities, tend to be equipped with tunnels to accommodate baggage systems, in-line security baggage systems, or maintenance and utilities, making them relatively safe places of shelter during a tornado or high winds. However, in some cases these tunnel areas are in a Secured Area of the airport, so typically the airport will be closed for the duration of the storm and will stay closed until all passengers and unauthorized personnel are relocated back to the public areas and the Secured Areas have been searched.

Airport fire personnel should track the status of incoming severe weather and natural disasters, and they should prepare to render aid and assist the airport operator in taking Protective Actions. To protect personnel working on the ramp, airports experiencing severe thunderstorms accompanied by lightning routinely shut down ramp operations (which also shuts down flight operations), when there is lightning within a specified range4 of the airport. In this case, the “evacuation” is not individuals from the terminal building to another location, but from the ramp areas to inside the terminal building and concourses.

In some situations, personnel who are warned of a threat may not take any action. One of several illogical reactions that people can have during an emergency is the failure to move out of harm’s way. In her book, The Unthinkable: Who Survives Disaster and Why, Amanda Ripley posits that people respond better to warnings when they are told: (a) what specifically to do; (b) why they must do what is requested; and (c) the potential threats that could impact them (Ripley, 2009).

During the 9/11 evacuation of the World Trade Center towers, people waited an average of 6 minutes before heading down the stairs, with some waiting as long as 45 minutes. Failure to act in the face of a threat is a classic fight-or-flight response. Some individuals enter a temporary state of denial, saying to themselves, in effect, “this is not happening, it is not happening now, nor is it happening to me” (Ripley, 2009, p. 9). In 1960, an earthquake in Chile triggered a tsunami that headed for the Hawaiian Islands. Despite the warning sirens, which worked as advertised, most of the people who heard the siren did not evacuate, because they were not sure what the warning meant (Ripley, 2009, p. xiii).

If Ripley’s research was applied to a tornado warning message sent to occupants of an airport terminal building, the message could say: “Attention all personnel in the airport terminal, a Tornado Warning is in effect, please proceed immediately to a tornado shelter. Look for signs labeled Tornado Shelter to prevent injury from shattering glass and flying debris. The airport is temporarily closed, and all flights are being held until the warning is canceled.”

Any evacuation or shelter-in-place procedure must take into account individuals with functional needs. According to Dory Clark, Assistant Executive Director for The Arc, in Houston, Texas, it is illegal for a public-use airport to direct individuals with functional needs to use alternative evacuation points that do not provide the same level of protection and the same speed of egress as routes for those without functional needs (Clark, personal communication, 2015). It is also illegal for a public use airport to tell individuals with functional needs that they will have to wait until able-bodied individuals have evacuated before they can be evacuated (Clark, personal communication, 2015).

Individuals with functional needs or special needs include those with a hearing impairment, a visual impairment, physical disabilities, mental or emotional disabilities, unaccompanied children, elderly individuals, and even individuals with learning disabilities like dyslexia or the inability to read. It is also important to understand that passengers who do not have a clinical diagnosis for a particular condition may experience severe cases of anxiety in crowded or stressful situations or have other stress-induced health issues. Many passengers require access to medicines, and in some cases, medicines that require refrigeration. Some passengers may carry enough medicine to handle short-term shelter-in-place situations, but for extended situations, such as during a blizzard, that may shut down the airport for days and force thousands of passengers to stay in the terminal building, accommodations for refrigeration for medicines, and the need to evacuate some personnel because of medical needs, must be considered.

Not all personnel in the airport speak English, particularly at international airports, so public address announcements should also be scripted in other languages that are used in the region or that match up to the international carrier routes. For example, if Lufthansa flies out of the airport, prerecording a public address announcement in German would be logical. If Mexico is a primary service destination for airlines at the airport, it makes sense to have prerecorded announcements in Spanish. Also, apps are available that can help customer service personnel in translating various languages, and some services are also available by phone that allow an airport or airline customer service agent to call an interpreter, who can relay messages to passengers. Airport Ambassadors, or airport customer service personnel, should have these apps or phone numbers available.

For extended shelter-in-place situations, airports often keep extra supplies of blankets, pillows, and cots and have worked out contingency contracts with airline caterers to provide food. Many airport vendors and restaurants rely on daily deliveries of food and beverages to the airport, particularly refrigerated food, and cannot sustain operations for more than a day without resupply. Military meals-ready-to-eat (MREs) and a massive quantity of stored bottled water may be an option for some airport operators who desire to have sustenance options, particularly airports located in areas prone to hurricanes, where operations and community services may be shut down for days or weeks.

Another important component of Protective Actions is the protection of employees who are responsible for implementing the Protective Actions portion of the AEP. When hundreds or thousands of individuals are forced to shelter-in-place, disruptions, arguments, and fights can occur between passengers, placing Airport Operations personnel in harm’s way. Therefore, adequate police coverage and proper deployment of law enforcement personnel to areas of concern should be addressed in the planning process.

For some large-scale disasters, such as hurricanes, or severe weather leading to numerous tornadoes, such as occurred in the storms of 2011 throughout the Midwest, Airport Operations are often forced to shut down completely. Airport employees who are responsible for implementing actions under the AEP also have families and homes they are worried about. Airport management must take these natural desires—to take care of one’s family and home—into consideration in the AEP. Personnel who are more worried about what’s going on at home, and who have not been home for days or even heard if their family is okay, will not be effective at their job. The AEP should take into account reduced levels of operation because of personnel not showing up for work because of the inability to access the airport (damaged or washed-out roads, or community destruction that prevents them from getting to work) and allow the airport management to rotate essential personnel home to take care of personal needs.

When an entire community is affected by a power outage or natural disaster, a get-home-kit may be useful for getting employees home if they need to walk home or to another place of shelter (Anders, 2015, pp. 71–72). The kit should be a backpack, not a laptop or shoulder bag, as the individual may have to walk many miles. At a minimum, the kit should contain an adequate supply of bottled water, a lighter, a first aid kit, some high-calorie ration bars or protein bars, and a flashlight. If possible, a small knife, or a Swiss Army Knife or Leatherman, is useful, but may be prohibited in some workplaces. Some comfort items like a roll of toilet paper, an extra set of clothes, and a couple of pairs of socks and spare underwear are also advised, along with possibly a pair of sneakers or old comfortable boots, which can be tied to the outside of the bag to save space. A Mylar space blanket and hand-crank radio can also come in handy (Anders, 2015). Spare medicines when possible, along with any other essential item, such as batteries, a cell phone battery charger or backup battery, and a hat, gloves, and rain slicker, can also fit into a standard-sized backpack. While many personnel may not keep a kit at their desk all the time, they can be encouraged to create one if a hurricane or other foreseeable natural disaster is pending.

While the Protective Action section of the AEP AC says that this section of the emergency plan should address human-made and natural disasters, the AC was written in 2010, 3 years before the second active shooter incident since 9/11, at Los Angeles International Airport. Therefore, most of the AC focuses on natural, not human-made, disasters. An active shooter incident is significantly different from a pending natural disaster. Most natural disasters, such as a hurricane, tornado, severe thunderstorm, or blizzard, come with some advance warning. Some natural disasters, such as earthquakes, can occur with little to no warning, but airports located in areas known for the frequency of earthquakes typically have (or should have) contingency plans for such events, and the local populace often knows how to respond to an earthquake. However, active shooter situations are different.

An active shooter incident is not so much an evacuation as it is an escape. It is not so much a shelter-in-place as it is a “run-hide-fight.” While some of the Protective Actions relevant to natural disasters can be used during an active shooter event, separate contingency plans should exist. Evacuations are usually somewhat orderly, following established evacuation routes with the assistance of airport personnel. Recovery from an evacuation is also rather orderly, compared to recovery from an active shooter escape. During an active shooter incident, there is no evacuation plan per se, as the primary goal is to escape from the line-of-fire as quickly and effectively as possible. During the Los Angeles International Airport active shooter event on November 1, 2013, thousands of passengers and airport employees streamed onto the ramp through fire alarm access doors as fast as possible. Recovery from such an escape will usually take much longer than recovery from a standard evacuation because of a pending storm as individuals do not follow established evacuation routes and are literally running for their lives. It is unreasonable to think people will follow standard evacuation protocols with someone shooting at them, so airport management should be less concerned with the methods of escape and focus on shutting down aircraft operations, notifying individuals who may be in harm’s way that they need to run for cover or safety, and locating and neutralizing the shooter. Protective Actions, particularly during an active shooter event, reinforce the need for the airport operator to install panic alarms and have publicly posted phone numbers to call in the event of an emergency.

Law Enforcement and Security

Title 14 CFR Part 139 does not have specific law enforcement requirements; however, many of the emergency plan’s actions require police or some sort of security component. Additionally, commercial service airports that are regulated under Title 14 CFR Part 1542 require that the airport operator provide law enforcement to a level that is adequate to respond to the screening checkpoints, to support the ASP, including contingencies and incidents, and to respond to incidents of unlawful interference with civil aviation. The primary function of police on the airport is the enforcement of law, to support the ASP, and to support the contingencies and incident management plans within the AEP and the ASP.

Certain incidents such as bomb threats, active shooter, actual detonations of explosives, and hijackings will require immediate police response, and some situations may require additional support such as Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) and K-9 teams or the FBI. During a natural disaster or airplane crash, law enforcement primarily is responsible for scene security and access control to the scene, Staging Areas, family assistance rooms, or in other areas where protection is needed (Figure 11.3 ).

Figure 11.3.

Some airport police departments have mobile x-ray equipment and “Raider” vehicles, like this one pictured at left (Port Authority of New York and New Jersey). The Raider allows the rapid response and stable deployment of air-stairs to the access door of an airliner.

Off-airport police or other law enforcement personnel may need to respond, depending on the situation. It is up to the police agency at the airport to ensure that off-airport responders know how to access the airport in a safe and proper manner. During some airport emergencies, local police and sheriff personnel have been known to access an airport by either driving through a gate or fence (knocking it down) and proceeding across aircraft movement areas without clearance, to respond to wherever they see smoke or perceive the incident to be (see Figure 11.4 ). These situations can cause runway incursions and potential collisions with aircraft. Offsite responders should be provided grid maps and simple instructions on where to respond at the airport and the importance of waiting for an escort to the incident site. Training with offsite responders is a way to reduce these safety incidents but still retain the benefit of police presence during an emergency.

Figure 11.4.

An ARFF truck responds during an emergency exercise at Centennial Airport, CO.

Law enforcement personnel take the lead for any security incident at the airport and should be adequately trained and equipped to respond to any security issue, Aircraft Accident, structural fire, or other hazard in the AEP. During a hijacking or bomb threat, FBI hostage-response teams or special weapons response teams may take hours to get into position. Airport police are the first line of response and should know the procedures for securing the area in the event of a bomb threat, how to handle a bomb threat on an aircraft, and the procedures for handling a potentially hijacked aircraft that is on the airport or inbound to the airport. An important note: the TSA’s Federal Security Director (FSD) has the authority to assume Incident Command for any security incident at an airport, but the FSD typically does not have any available armed response forces. TSA Transportation Security Officers and Transportation Security Inspectors are unarmed and are not trained in law enforcement response procedures.

Although air marshals are TSA personnel and are armed and trained law enforcement officers, under Part 1542 it is still the airport operator’s responsibility to respond to the threat using its own police force. Depending on the relationship between the air marshals based at the airport (if the airport is a Federal Air Marshal [FAM] base), local police may call on air marshals for assistance. If available, an Assistant Federal Security Director for Law Enforcement (AFSD-LEO) (a TSA law enforcement officer) may help facilitate federal agency response until the FBI is on-scene. However, AFSD-LEOs are very few and far between, so it’s a good assumption for airport police to believe that they are on their own, at least for the first 30 to 60 minutes of an event. In some cases, airports are located on or near military bases and may have military special operations teams that can respond to an act of unlawful interference with aviation. This response option should be addressed in the ASP and familiarization training conducted with these off-airport response teams.

Airport law enforcement personnel should also work with local jurisdictions to provide additional support via air, land, and water, if appropriate, to respond to airport incidents. The airport law enforcement coordinator must ensure that a representative responds to the EOC or Incident Command center during an emergency and must ensure that all equipment, radios, and other materials are in proper and working order and ready to support the AEP and ASP.

Some airports use unarmed security officers to provide staffing for airfield vehicle gates, and general patrol of the airfield and terminal areas, to respond to security alarms, and watch for and respond to potential violations of the Airport Security regulations. While other security personnel cannot meet the TSA regulatory requirements for law enforcement personnel at an airport, they can be used as a force multiplier by enforcing the ASP and responding to alarms, freeing up police officers for other duties.

Firefighting and Rescue

Firefighting and rescue personnel provide emergency services to the airport that may affect life, property, and safety. While Part 139 requires a certain level of ARFF response to Aircraft Accidents and incidents, the AEP extends those responsibilities to structural fires and hazards, hazardous material (HAZMAT) incidents, and emergency medical response. The AEP must describe the level of firefighting capability, along with the number of personnel, the location and number of vehicles and support equipment, and outside agency support (FAA, 2010, p. 75). Although dedicated to ARFF response, some airport fire crews often provide response to the terminal building to provide emergency medical care, and at large airports, the fire department may have additional specific terminal (structural) and landside-response fire-rescue equipment (Figure 11.4).

Some airports maintain structural firefighting capabilities and on-scene paramedics or emergency medical personnel. At airports without such capabilities, the AEP must address how offsite responders will provide the services, including how they will be notified and how they will access the airport. As previously mentioned, some airports rely on military fire and rescue services, so the airport operator should ensure that military ARFF equipment and personnel meet the Part 139 requirements.

The ARFF chief must ensure compliance with all ACs related to ARFF training standards and regulations and HAZMAT standards and ensure the readiness of all necessary equipment. ARFF personnel are required to participate in one live-burn exercise annually and to participate in the triennial emergency exercise.

At most airports, the Fire Chief or senior firefighter officer on duty will assume Incident Command for an airplane crash or other related incident. Fire and rescue personnel are responsible for the Priorities of Work (saving lives, scene stability, protect property, protect the environment), but once the incident is stabilized and recovery operations are underway, Incident Command typically shifts to Airport Operations or airport police. A representative from the fire department is expected to respond to the EOC, for most airport emergencies.

Fire and rescue personnel must also support HAZMAT issues, including fuel spills. Typically, only large airports have significant HAZMAT response capability. At smaller airports, HAZMAT response is often the responsibility of an off-airport unit. Fire personnel and equipment also support security incidents by providing lifesaving services, putting out fires, and managing any fire alarms that may have been activated during a security incident.

ARFF personnel that drive on the airfield must be trained and authorized to be in the AOA, and an airport grid map should be available in every fire and rescue vehicle. Specific duties for ARFF personnel and other fire and rescue personnel are addressed in the hazard-specific section of the AEP.

Health and Medical

Airports often experience high levels of demand for health care services. Some passengers experience higher levels of anxiety during air travel, some passengers’ preexisting medical conditions may be exacerbated by thinner air as a result of a pressurized airline cabin or as the result of traveling to a higher altitude, and some passengers may be sick or may become injured during travel. The airport operator should have available EMSs to treat conditions such as cardiac arrest, abdominal pains, burns, cuts, abrasions, and communicable diseases, as well as other medical problems (NFPA, 2013, pp. 424–28).

Today, it is normal for airport firefighters to also be trained as EMTs, or at least in Basic Medical Care, and many Airport Operations personnel are trained in first aid, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and critical trauma care. Some airports have first-aid treatment facilities with limited resources, but enough to treat most of the common injuries and ailments experienced by passengers (slip and falls, airsickness, headaches, etc.). Automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) are effective in certain cardiac events and should be positioned throughout the airport (NFPA, 2013, pp. 424–28).

The AEP must address how the airport operator will mobilize assets and respond to health and medical issues and the specific agency that is responsible for providing health and medical services. Any Part 139 certificated airport is required to have at least one individual on-duty, usually a firefighter, who is trained in Basic Medical Care. However, this training requirement is not equal to the level of Paramedic or EMT, and at any large commercial service airport, one medic will not be enough to handle the health and medical demands of the airport population.

Most airports cannot sustain health and medical capabilities beyond initial first aid and trauma care during a mass casualty incident and require assistance from outside entities. The AEP must describe the airport’s ability to provide medical care, treatment, and transportation of victims during an aircraft crash or airport incident, describing also any public and private medical facilities and mortuary services available at the airport or in the community. Such entities should understand their role and requirements under the AEP, and the AEP should include the name, location, contact information, and emergency capability of each hospital and other medical facility that agrees to provide medical assistance or transportation (FAA, 2010).

The AEP should identify hangars or other buildings to be used for the staging of personnel, uninjured, injured, and deceased. The senior medical coordinator should ensure that a health and medical representative responds to the EOC (and the Incident Command Post), and that provisions are made for transportation of the wounded to proper medical facilities. All ambulances or other emergency medical vehicles should be equipped with a grid map of the airport and provided either with an escort to the accident site or a clearly marked pathway (using cones, barricades, and airport personnel) to ensure safe access to the site, particularly when the airport continues to be operational. The senior medical coordinator should also know the process for requesting support of the various Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMATs), which are part of the resource typing categories in NIMS, and the Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Teams (DMORTs).

Medical personnel are responsible for triage of the injured, transportation of critically injured to medical facilities as quickly as possible, ideally within 60 minutes, and identifying and arranging for the transport of the deceased.5 During a HAZMAT incident, medical personnel are responsible for isolating, decontaminating, and treating victims as needed; however, airport fire personnel typically take on the role of initial decontamination of victims. Environmental health officers should also be appointed to monitor and evaluate health risks, inspect damaged buildings for health hazards or contamination, and ensure sanitary facilities in emergency shelters are available. Other key medical functions include coordinating with the American Red Cross and Salvation Army to provide food for both responders and patients, assist the air carrier in family member notifications, assist those with functional needs, and assist orphaned children and children separated from their parents, along with coordinating with veterinarians and animal hospitals to provide care as needed to those involved in the incident.

Communicable Diseases

As much as aviation allows us to travel the world in a matter of hours, it can spread a communicable disease from one side of the planet to the other just as quickly. Air travel reduces the time available for countries and airports to prepare interventions and stockpile antidotes. The primary goal of the airport operator is to protect the health of passengers, staff, and the general public. In 2009, Airports Council International (ACI) issued a communiqué on the responsibilities of airports to mitigate the effects of communicable diseases, health screening practices, and how to handle an inbound aircraft carrying a passenger with a suspected case of a communicable disease, which can pose a serious health risk (ACI, 2009).

Approximately 1.7 million passengers arrive daily in the United States on commercial passenger flights, with each large aircraft carrying more than 300 passengers and crew (ACI, 2009). This number does not take into account passengers and crews arriving on general aviation aircraft into the United States. The threat of pandemic flu, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Ebola, and other viruses spreading through the air transportation system has caused airport operators to consider options for handling individuals who may be infected and require quarantine, or even quarantine of an aircraft or the entire airport population.

Many airports have installed hand cleaner dispensers in the rest rooms and throughout the terminal building, and signs encouraging passengers and employees to wash their hands to prevent the spread of infectious or communicable diseases.6 To further reduce the risk of spreading communicable diseases, ACI encourages airports to develop an Airport Preparedness Plan that addresses how the airport will communicate with the public about the potential for a communicable disease outbreak or issue, the implementation of screening processes for communicable diseases, methods to transport passengers to health facilities, and having on hand the necessary equipment to conduct the screening along with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) to reduce the risk of airport staff contracting a disease. Furthermore, airports should coordinate response plans with local, state, and federal public health authorities prior to an outbreak.

Communication is critical to preventing an outbreak or spread of communicable disease. Airports should leverage their notification processes that are already in place and outlined in their AEP to ensure that quick methods are available to get in touch with air carriers, tenants, vendors, contractors, and others working at the airport, along with passengers and the media. Information can be given to passengers prior to arrival at the airport through airport and airline websites, a dedicated telephone line that passengers can call to receive the latest information, and through normal mainstream media pathways (ACI, 2009).

The World Health Organization (WHO) says that screening for communicable diseases can reduce the opportunity for transmission or delay an international spread (ACI, 2009). A variety of screening methods are available, including visual inspection to look for obvious signs of illness or symptoms of particular diseases, and the use of thermal scanners or other suitable methods to take the temperature of inbound passengers from international destinations. Passenger interviews and questionnaires, along with identifying flights that have been routed through countries with known infectious disease outbreaks, are other methods of attempting to identify individuals with communicable diseases (ACI, 2009).

Health screening usually takes place at the Federal Inspection Areas of the airport. Airport operators should ensure at least one individual from the airport is appointed to keep up with the latest information coming out of the WHO and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) on the latest epidemiological and virological findings, along with the geographical distribution of infected persons and suggested screening measures (ACI, 2009). In some circumstances, screening is conducted at the airport of departure, but that cannot always be counted upon. It’s important that passengers are screened as soon as possible upon entering the airport and definitely before being allowed out of the Federal Inspection Service (FIS) area. A simulation model conducted as part of a study on U.S. airport entry screening in response to pandemic influenza (CDC, 2009) found that foreign shore exit screening significantly reduces the number of infected passengers while U.S. screening identifies 50% of the infected individuals.

In 2014, approximately 80,000 passengers departed by air from the three countries most affected by Ebola: Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone; approximately 12,000 of these passengers were en route to the United States. Procedures were implemented to deny boarding to ill persons and persons reporting a high risk of exposure to Ebola; however, no passengers who were denied boarding for fever or other symptoms or reported exposures were subsequently diagnosed with Ebola. Of those permitted to travel, none are known to have had Ebola symptoms during travel and none have been subsequently diagnosed with Ebola, but two passengers to the United States, who were not symptomatic during exit screening and travel, became ill with Ebola after arrival. CDC enhanced its procedures for detecting ill passengers entering the United States at airports by providing additional guidance and training to Customs and Border Protection (CBP) personnel, airlines, airport authorities, and EMS units at airports; the training covers recognizing possible signs of Ebola in travelers and reporting suspected cases to CDC (CDC, 2014).

If during the screening process a passenger is determined to be a health risk of having a communicable disease, they should immediately undergo a more extensive evaluation by a medical professional. Quarantine facilities should be previously designated, and protocols for handling potentially infected individuals should be in place.

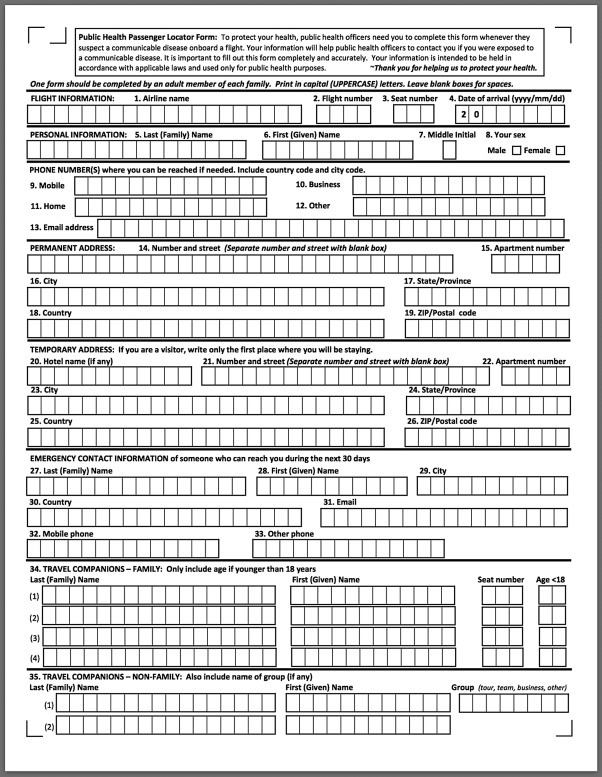

If an inbound aircraft is carrying an individual that may have a communicable disease or an infectious disease, or an ill person7 with an unknown cause, the pilot in command should be notified as soon as possible and advised of where to park the aircraft. The aircraft may even be diverted to another airport. Ideally, the aircraft should be parked away from the concourse or terminal building, on a remote stand or area of the airfield, and either with a separate passenger boarding bridge or air stairs (ACI, 2009). Passengers should be taken off the aircraft as soon as possible and provided with information about what is happening and what to do if they experience symptoms later on. The WHO publishes a Passenger Locator Card that can be used to track passengers who were on the affected flight (Figure 11.5 ). All passengers should be required to fill out the card. Methods should also be in place to handle screening of those arriving by general aviation aircraft into both commercial service and general aviation airports. Sick passengers should be taken to an isolation or quarantine area by personnel wearing the appropriate protective equipment, with procedures in place to obtain the passengers' bags and personal belongings, and provisions made for customs and immigration personnel to properly, and safely, process the individuals into the country.

Figure 11.5.

Passenger Locator Card.

Source: World Health Organization.

The decision whether to quarantine an entire flight or airport population must be taken with great consideration. A large-scale quarantine will have a significant impact on flight operations at that airport and throughout the National Airspace System. Airport Cooperative Research Program (ACRP) Report 5 addressed the questions of deciding whether to quarantine and how to go about it (Stambaugh, Sensenig, Casagrande, Flagg, & Gerrity, 2008). The quarantine of an entire airport would involve a massive mobilization of community and federal resources, but the ACRP study was based on a more basic assumption, which would be to effectively quarantine up to 200 passengers from an international flight for a period of 2 weeks. The study addressed the four phases of quarantine: (1) the decision to quarantine, (2) establishing quarantine, (3) quarantine operations, and (4) demobilization and recovery.

The study revealed the estimated cost to acquire and maintain the basic supplies to accomplish such a quarantine would exceed $100,000, a cost that does not take into account the cost of the space that would be needed for the quarantine, which was estimated to be $15,000 per month (depending on local variances) (Stambaugh et al., 2008). Quarantine operations would include establishing accommodations and renting showers and portable toilets, which could cost up to another $20,000 or more, plus another $150,000 or more to provide lodging, food, recreation, communications, sanitation, basic health services, security, and cleaning (Stambaugh et al., 2008).

However, the decision to impose a quarantine order on international travelers lies with the CDC, not the airport or an airline. Airlines have a duty to report certain illnesses, but only federal public health officials are authorized to implement a quarantine. The CDC may also choose less-extreme measures, such as a voluntary home quarantine, vaccinations, or collecting passenger information cards with follow-up by public health officials to determine if anyone develops symptoms, as occurred during the 2003 SARS outbreak (Stambaugh et al., 2008).

Once the decision is made to quarantine passengers, health officials must decide where individuals exhibiting symptoms will be taken, as well as how and where to put the remaining passengers. Keeping passengers on the aircraft for an extended period of time is not desirable. A site must be located, along with a method of transportation to get the passengers and crew from the aircraft to the facility. Vehicle operators and other personnel involved with moving the passengers and crew will also have to take protective measures (Stambaugh et al., 2008). Individuals with functional needs must also be accounted for; thus, wheelchairs and a lift service may be necessary to help some passengers off the aircraft into the quarantine facility.

The quarantine location should have accommodations for sleeping, bathing, entertainment, and communications, plus access to medical care, along with supplies and staffing for food preparation, cleaning, counseling, or additional considerations. If the quarantine facility is offsite, these responsibilities shift to the CDC or state and local health providers, but the airport operator still must ensure that the aircraft, along with any personnel involved with the quarantine, are properly taken care of. The aircraft must be cleaned, and airport and airline personnel involved in the quarantine operation must be screened for symptoms. From an airport operator perspective, one should conclude that these individuals would be out of commission and out of the work schedule for at least a few days.

If the quarantine facility is on the airport, the airport operator will likely be more involved with providing access to the facility and possibly providing support for the quarantine operation. Additionally, the CDC may only use an on-airport facility temporarily, which will necessitate another transfer of potentially affected passengers and crew, followed by a proper cleanup of the facility that was used. At the end of the quarantine, passengers and crew may still need to finish their journey, which may require providing transportation back to the airport to rebook passengers on other flights.

Resource Management

The airport operator must ensure a list of resources is available to decision makers during an incident. Airport operators must assume that during an incident, particularly a natural disaster, there will be critical shortages of power, potable water, firefighting agents, and portable equipment, such as lights and generators, and further that emergencies will deplete the resources of responders quickly. Local transportation systems may also be affected by the disaster (bridges collapsed, highways blocked or damaged), making the replenishment of resources difficult or not possible for a period of time. However, airports do have a benefit in that they are not limited by highway transportation methods. Airports have historically accepted relief aircraft bringing in aid and resources to a community during a natural disaster by both Fixed-Wing aircraft and helicopters.

Resource typing is essential to ensuring that the necessary resources are identified and available for use when needed. Additionally, a resource manager should be appointed to ensure that all agencies are maintaining resources in a readiness state and that key points of contact, purchasing contracts, and other elements necessary to ordering up resources are in order.

A complete list of resources should be included in the appendix of the AEP that includes personnel (i.e., volunteers, off-airport responders), communications equipment, vehicles, heavy equipment, portable pumps and hoses, postincident recovery materials, such as tools, fuel, sandbags, and lumber, portable power generators, and mass care supplies (first aid, potable water, blankets, and lighting) (FAA, 2010, p. 90). Any resources that are not available at the airport that must be provided by a mutual aid organization should also be noted.

All response agencies should be self-sustainable for the first 24 hours of an incident; this standard helps to identify how many resources will be needed. Resource typing includes determining what is needed, why it is required, how much, who needs it, where it needs to be delivered, and when it is required. The Supply Group within the Incident Command structure will first try to fill resource needs with airport resources and then notify suppliers, negotiate terms, and arrange for transport of resources as necessary. The finance and administrative team should be kept aware of budget issues, with all transactions being properly recorded (FAA, 2010, p. 92).

After the emergency, the resource manager or the logistics unit within the Incident Command structure is responsible for disposing of excess stock, reimbursing owners for property or use of equipment, acknowledging suppliers, donors, and volunteer agencies, and exploring potential future agreements and contracts that will better facilitate resource needs in the future.

Airport Operations and Maintenance

Even though the day-to-day roles of Operations and Maintenance are separate, the AEP AC treats them as a singular component in the emergency response context. However, many airports have very clear lines of distinction between the roles of Operations and Maintenance during an emergency. The Operations and Maintenance section of the AEP outlines the overall statement of capabilities and responsibilities of operations and maintenance personnel during an emergency.

The AC acknowledges that often Airport Operations or Airport Maintenance personnel are the first to respond to many airport emergencies, as a result of the nature of their duties, which requires them to be either in the airfield or in the terminal building most of the time. Airport Operations personnel represent airport management throughout the stages of an emergency, and they may have to establish Incident Command and act in the capacity as the IC either during the initial or other stages of the emergency. At some small non-hub airports, Airport Operations personnel are not onsite 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, so other arrangements must be made to notify Operations and Maintenance personnel of an emergency at the airport. Fixed Base Operators (FBOs), or air carriers operating at the airport after Operations and Maintenance personnel have completed their duty day, may have the responsibility for notifying an on-call airport representative, or local first responders may have to make the contact.

Primarily, the role of Airport Operations in an emergency is based on their assigned mission within the AEP and is airport-specific. Generally speaking, Operations ensures that all notifications have been made, will either assume Incident Command or support the IC by providing resources and communications services, and makes the initial determination regarding the issuance of a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) to close a portion of or the entire airport.

Airport Maintenance personnel, if they are not required to be actively engaged in the emergency, will typically stand by and respond to requests for assistance from various response agencies. Many airfield maintenance personnel are trained in operating vehicles on the airport and can be highly effective at providing escorts for off-airport responders to get to an incident site. Maintenance personnel can also access supplies and equipment necessary for the support of the incident. A senior member of the maintenance department should also respond to the EOC in order to receive and coordinate requests for resources and assistance. A member of the maintenance department should also ensure that the command vehicle, mobile command centers, buses, and other vehicles are provided to the scene and are operational as soon as possible. All maintenance personnel who operate on the airfield should be provided with a grid map and should understand the procedures for notifying responders and other airport personnel during an emergency.

Maintenance personnel should maintain a resource list, ensure the safety of facilities during the recovery phase from a natural disaster, clear debris as necessary, provide sanitation services, potable water, and backup electrical power, transport portable emergency shelters to appropriate locations, and provide heavy equipment, cones, stakes, flags, and signs. Many large airports also keep buses equipped with body bags, blankets, cots, stretchers, and other items necessary to support an aircraft crash response.

Airport Operations personnel ensure compliance with regulations during and after emergency operations, noting any violations of regulations that occurred to facilitate the response. Operations personnel should follow up with any regulatory violation by properly notifying the FAA, TSA, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), or other appropriate agency. During the recovery phase, Airport Operations, if they do not already have the Incident Command responsibility, will typically take over IC responsibilities and oversee the recovery phase to get the airport back to full operation.

The Airport Emergency Command Center and Operations

It is often said that all emergency management is local. This statement reflects the approach taken by the United States when it comes to a local disaster. Initially, local response is supposed to handle the event, disaster, or incident, but when local resources are overwhelmed, the municipality calls on the state to assist. When the state’s resources are overwhelmed, then a request is made to the federal government. This concept is reflected on an airport, where most emergencies are handled by Airport Operations personnel, firefighters, police, security, and emergency medical personnel and are supported by the airport’s communications or dispatch center, without the need to activate a large, Incident Command structure beyond the single IC. A single Incident Command post is established on-scene, with the communications center providing logistical support, overall communications, and coordination. In essence, the communications center8 functions as a lesser emergency command center for small-scale incidents.