ACROMEGALY

Definition

Acromegaly is a chronic, progressive disorder caused by growth hormone (GH) hypersecretion after normal growth cessation. Excess GH production before epiphyseal closure results in gigantism.

General aspects

Aetiopathogenesis

GH hypersecretion is usually caused by an eosinophilic adenoma of the anterior pituitary. Other uncommon causes include pancreatic islet cell tumours and some lung endocrine tumours that produce GH stimulating factors.

Clinical presentation

▪ Excess tissue growth (Fig. 3.1 ): • supra-orbital ridge (prominent) • nose (broadened) • skin (thickening) • macroglossia • mandible (spaced teeth, prognathism) • hands and feet (large) ▪ Systemic complications due to organ enlargement: • diabetes • hypertension • cardiomyopathy ▪ Local effects of pituitary tumour (headache, visual defects).

Figure 3.1.

Clinical presentation of acromegaly

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is confirmed by clinical, laboratory and radiographic findings: ▪ plasma GH – raised ▪ oral glucose tolerance test – fails to suppress GH ▪ serum insulin-like growth factor 1 – raised ▪ CT and MRI.

Treatment

▪ Neurosurgery and/or radiation ▪ Dopamine agonists (bromocriptine) and somatostatin analogues (sandostatin).

Prognosis

Acromegalic patients have a decreased life expectancy, because of cardiovascular diseases, tumours and endocrine problems. Cardiac failure is the major cause of death.

Oral findings

▪ The skull is thickened and the paranasal air sinuses are enlarged ▪ Mandibular enlargement leads to class III malocclusion with spacing of the teeth and thickening of all soft tissues, but most conspicuously of the face ▪ Enlargement of the dental bases leads to relatively sudden ill-fitting dentures ▪ Macroglossia and thick lips are due to soft tissue growth ▪ Apical hypercementosis ▪ Sialosis ▪ Hyperpigmentation of the naso-labial fold ▪ Progressive periodontal disease has been described – probably related to dental malposition and tissue enlargement.

Dental management

Risk assessment

Dental management may be complicated by: ▪ visual impairment ▪ cardiomyopathy ▪ cardiac arrhythmias ▪ hypertension ▪ diabetes mellitus ▪ hypopituitarism.

Rarely, acromegalics have Cushing's syndrome or hyperparathyroidism due to associated multiple endocrine adenoma syndrome.

Preventive dentistry and patient education

The abnormal skeletal growth may result in carpal tunnel syndrome, and an enlarged tongue, leading to difficulty with toothbrushing. An electric toothbrush may be beneficial in these circumstances.

Patient access and positioning

Obstruction of the upper airway may be associated with sleep apnoea and fatigue. Such patients should be seen later in the day when they are rested, with the dental chair positioned more upright to avoid further collapse of the airway. If available, longer dental chairs, or chairs which can be extended, are useful to increase patient comfort during treatment.

Pain and anxiety control

Local anaesthesia

Hyperpituitarism does not affect the selection of local anaesthetic.

Conscious sedation

There are no contraindications regarding the use of conscious sedation.

General anaesthesia

Kyphosis and other deformities affecting respiration may make general anaesthesia hazardous. The glottic opening may be narrowed and the cords' mobility reduced. A goitre may further embarrass the airway.

Table 3.1.

Key considerations for dental management in acromegaly (see text)

| Management modifications* | Comments/possible complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk assessment | 2 | Blindness, diabetes, hypertension, arrhythmias |

| Preventive dentistry and education | 1 | Carpal tunnel syndrome, enlarged tongue |

| Pain and anxiety control | ||

| – Local anaesthesia | 0 | |

| – Conscious sedation | 0 | |

| – General anaesthesia | 1/4 | Kyphosis, narrow glottis |

| Patient access and positioning | ||

| – Access to dental office | 0 | |

| – Timing of treatment | 1 | Sleep apnoea, fatigue |

| – Patient positioning | 1 | Longer dental chair |

| Treatment modification | ||

| – Oral surgery | 0 | |

| – Implantology | 0 | |

| – Conservative/Endodontics | 0 | |

| – Fixed prosthetics | 0 | |

| – Removable prosthetics | 0 | |

| – Non-surgical periodontology | 0 | |

| – Surgical periodontology | 0 | |

| Hazardous and contraindicated drugs | 0 | |

0 = No special considerations. 1 = Caution advised. 2 = Specialised medical advice recommended in some cases. 3 = Specialised medical advice mandatory. 4 = Only to be performed in hospital environment. 5 = Should be avoided.

Treatment modification

Surgery

Orthognathic surgery may be considered, although fatalities have followed such surgery in the past, because of airway obstruction.

Periodontology

Early treatment and regular review are important to control periodontal disease progression.

Drug use

No antibiotics or analgesics are contraindicated.

Further reading

- Brennan MD, Jackson IT, Keller EE, Laws ER, Jr, Sather AH. Multidisciplinary management of acromegaly and its deformities. JAMA. 1985;253:682–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan J, Redpath T, Buckle R. The medical and anaesthetic management of acromegalic patients undergoing maxillo-facial surgery. Br J Oral Surg. 1982;20:77–83. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(82)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ADDISON'S DISEASE

Definition

Addison's disease is adrenocortical hypofunction due to the destruction or dysfunction of the adrenal cortex. It may be: ▪ primary – occurs when at least 90% of the adrenal cortex has been destroyed, and leads to low levels of both cortisol and aldosterone ▪ secondary – due to low levels of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), which causes a drop in the adrenal glands' production of cortisol but not aldosterone.

General aspects

Aetiopathogenesis

▪ Main cause is autoimmune (sometimes also associated with diabetes, Graves' disease, pernicious anaemia, vitiligo or hypoparathyroidism), particularly in women ▪ Rare causes include adrenal tuberculosis, histoplasmosis or tumours ▪ Secondary adrenocortical hypofunction may also follow an abrupt withdrawal from systemic corticosteroid therapy.

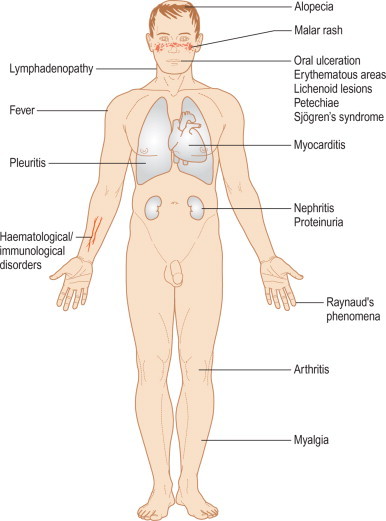

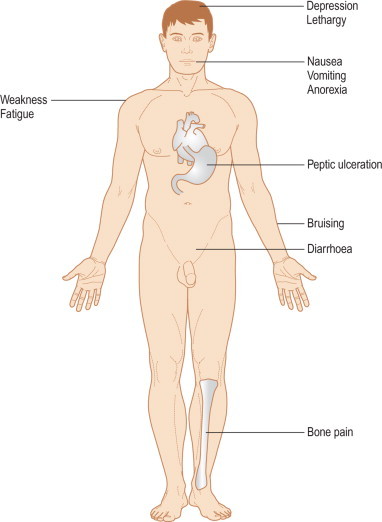

Clinical presentation

▪ Low cortisol leads to: • skin and mucosal hyperpigmentation (due to raised ACTH in primary disease; part of ACTH molecule is similar to melanocyte stimulating hormone) (Fig. 3.2 ) • hypotension (weakness, lethargy, tiredness, collapse) • weight loss ▪ Adrenocortical hypofunction may lead to shock and death if the individual is stressed as, for example, by an operation, infection or trauma.

Figure 3.2.

Clinical presentation of Addison's disease

Diagnosis

▪ Postural hypotension ▪ Plasma cortisol level – low ▪ Plasma sodium – low ▪ Plasma potassium – high ▪ ACTH stimulation test – impaired ▪ Adrenal antibodies.

Treatment

▪ Glucocorticoids (cortisone or cortisol) and mineralocorticoids (fludrocortisone).

Prognosis

Untreated patients may survive several months or years, followed by a progressive wasting of the body and death. Patients on steroid replacement therapy enjoy a normal life.

Oral findings

▪ Pigmentation of the mucosae of a brown or black colour is seen in over 75% of patients with Addison's disease. Hyperpigmentation predominantly affects areas that are normally pigmented or exposed to trauma (for example in the buccal mucosa at the occlusal line, or the tongue, and occasionally, the gingivae). ▪ Recurrent bacterial oral infections are not uncommon ▪ Chronic oral candidosis has also been described where there is an associated immune defect.

Dental management

Risk assessment

The danger of dental treatment in a patient with hypoadrenocorticism, especially when undertaking surgery under general anaesthesia, is of precipitating hypotensive collapse. Clinical findings suggestive of acute adrenal insufficiency include weakness, nausea, vomiting, headache and abdominal pain.

Acute adrenal insufficiency is managed as follows: ▪ call for immediate help ▪ lay patient flat with legs raised ▪ give hydrocortisone 200 mg IM ▪ oxygen 10L/min ▪ if IV access can be obtained, give 1 litre dextrose saline ▪ check blood pressure.

Appropriate oral health care

The need for patients on long-term steroid treatment to increase their dose of glucocorticoids when undergoing stressful procedures has been the subject of much controversy. In 1998, Nicholson et al reviewed all the available evidence and published new recommendations for steroid cover, where hydrocortisone supplementation is given intravenously. Patients who have taken steroids in excess of 10 mg prednisolone, or equivalent, within the last 3 months, should be considered to have some degree of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) suppression and will require supplementation. Patients who have not received steroids for more than 3 months are considered to have full recovery of HPA axis and require no supplementation. These guidelines have been adopted by anaesthetists in the UK (see Steroids) and are increasingly used by other specialties, including dentists.

However, the implementation of Nicholson's guidelines is not universal amongst the dental profession. Some are still using regimens such as doubling the normal daily steroid dose on the day of procedure (Gibson & Ferguson 2004).

Preventive dentistry

Oral hygiene and regular professional dental care are especially important, because increased susceptibility to infection has been described.

Pain and anxiety control

Cortisol levels normally increase in the postoperative period following oral surgical procedures. This increase is blunted by the use of analgesics, strongly suggesting that the increased cortisol levels are a physiological response to pain. Hence in patients with Addison's disease, postoperative analgesia is extremely important. In view of this, if significant postoperative pain is expected, the patient's usual steroid dose may be doubled on the following day.

Local anaesthesia

Adrenocortical hypofunction does not affect the selection of local anaesthetic

Conscious sedation

There are no contraindications regarding the use of conscious sedation.

General anaesthesia

The major determinant of secretion of ACTH and cortisol during surgery is recovery from general anaesthesia and extubation rather than the trauma of surgery itself. In these patients, steroid supplementation with 25 mg hydrocortisone at induction, followed by 100 mg/day for 48-72h are recommended.

Patient access and positioning

Patients with Addison's disease are best treated early in the day – when serum cortisol levels are highest.

Treatment modification

Most patients undergoing routine dental procedures need no supplemental steroids. However steroid cover is advisable for those patients undergoing surgical procedures, including dental extractions, periodontal surgery and placement of implants. It may also be considered for those patients that are particularly anxious. The guidelines recommended by Nicholson et al in 1998 are outlined below:

Perioperative steroid supplementation

Patients currently taking steroids (prednisolone)/stopped within last 3 months:

-

▪< 10 mg/day:

-

•assume normal HPA response – additional steroid cover not required

-

•

-

▪≥ 10 mg/day:

-

•Minor surgery – 25 mg hydrocortisone at induction

-

•Moderate surgery – 25 mg hydrocortisone at induction + 100 mg/day for 24h

-

•Major surgery – 25 mg hydrocortisone at induction + 100 mg/day for 48-72h.

-

•

Surgery

Delayed healing has been observed after dentoalveolar surgery. Antibiotic prophylaxis is advised before any procedure causing significant bleeding, including oral surgery, implantology and periodontal surgery. Good postoperative pain control is essential. Steroid cover should be considered.

Table 3.2.

Key considerations for dental management in Addison's disease (see text)

| Management modifications* | Comments/possible complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk assessment | 2 | Acute adrenal insufficiency |

| Appropriate oral health care | 2 | Consider steroid cover |

| Preventive dentistry | 1 | Increased susceptibility to infection |

| Pain and anxiety control | ||

| – Local anaesthesia | 0 | |

| – Conscious sedation | 0 | |

| – General anaesthesia | 2/4 | ACTH and cortisol secretion |

| Patient access and positioning | ||

| – Access to dental office | 0 | |

| – Timing of treatment | 1 | Early morning |

| – Patient positioning | 0 | |

| Treatment modification | ||

| – Oral surgery | 1 | Delayed healing |

| – Implantology | 1 | Delayed healing |

| – Conservative/Endodontics | 0 | |

| – Fixed prosthetics | 0 | |

| – Removable prosthetics | 0 | |

| – Non-surgical periodontology | 0 | |

| – Surgical periodontology | 1 | Delayed healing |

| Hazardous and contraindicated drugs | 0 | |

0 = No special considerations. 1 = Caution advised. 2 = Specialised medical advice recommended in some cases. 3 = Specialised medical advice mandatory. 4 = Only to be performed in hospital environment. 5 = Should be avoided.

Drug use

No local anaesthetics, analgesics, sedative drugs or antibiotics are contraindicated.

Further reading

- Bsoul SA, Terezhalmy GT, Moore WS. Addison disease (adrenal insufficiency) Quintessence Int. 2003;34:784–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson N, Ferguson JW. Steroid cover for dental patients on long-term steroid medication: proposed clinical guidelines based upon a critical review of the literature. Br Dent J. 2004;197:681–685. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson G, Burrin JM, Hall GM. Peri-operative steroid supplementation. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:1091–1104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CS, Little JW, Falace DA. Supplemental corticosteroids for dental patients with adrenal insufficiency: reconsideration of the problem. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:1570–1579. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziccardi VB, Abubaker AO, Sotereanos GC, Patterson GT. Precipitation of an Addisonian crisis during dental surgery: recognition and management. Compendium. 1992;13:518–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ALCOHOLISM

Definition

Alcohol, the most common drug of abuse, is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant. It initially releases inhibitions, impairs the capacity to reason, and interferes with the cerebellum, causing ataxia and motor incoordination. Eventually it interferes with higher centres, causing unconsciousness. Alcoholism is a psychological and usually also physical state, characterised by compulsive continuous or episodic consumption of alcohol (ethanol), with the objective of achieving some psychological effects or avoiding the unpleasantness related to alcohol withdrawal.

General aspects

Aetiopathogenesis

Prolonged alcohol abuse causes malnutrition, anaemia, impairment of immune function and other effects, including: ▪ CNS – memory loss, disinhibition ▪ liver – fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis ▪ GIT – gastritis, peptic ulcer, pancreatitis ▪ heart – cardiomyopathy, hypertension.

Clinical presentation

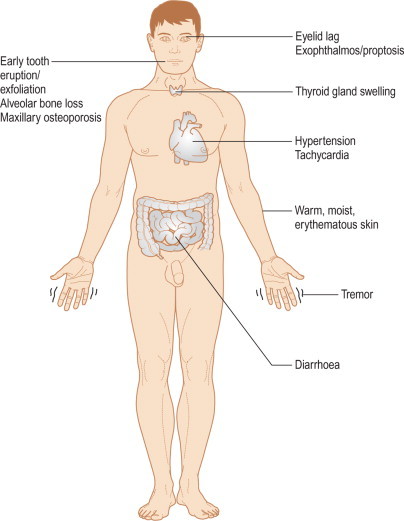

▪ Alcohol at blood levels above 35 mg/dL (35 mg/100 mL) impairs judgment, while signs of intoxication are clinically obvious at a blood alcohol level above 100 mg/dL, with slurred speech, loss of restraint and ataxia. At a blood alcohol level above 200 mg/dL some people become aggressive. ▪ Thus the acute effects of alcohol are mainly on judgment, concentration and coordination, and are dose-related as shown in Table 3.3 ▪ Earlier signs or symptoms of chronic excessive alcohol drinking include an evasive, truculent, over-boisterous or facetious manner, slurred speech, smell of alcohol on the breath, signs of self-neglect, gastric discomfort (particularly heartburn), anxiety (often with insomnia), or tremor ▪ Later signs or symptoms of chronic excessive alcohol drinking include palpitations and tachycardia, cardiomyopathy, liver disease, malnutrition, peripheral neuropathy, amnesia and confabulation (in Wernicke's and Korsakoff's CNS syndromes), cerebellar degeneration with ataxia, or dementia (Fig. 3.3 , Table 3.4 ) ▪ Alcohol can interact with other drugs such as warfarin, paracetamol/acetaminophen, and CNS-active agents such as benzodiazepines.

Table 3.3.

Acute effects of alcohol

| Blood alcohol level in mg/dL | Effect |

|---|---|

| <100 | Dry and decent |

| 100–200 | Delighted and devilish |

| 200–300 | Delinquent and disgusting |

| 300–400 | Dizzy and delirious |

| 400–500 | Dazed and dejected |

| >500 | Dead drunk |

Figure 3.3.

Chronic effects of alcoholism

Table 3.4.

Chronic effects of alcohol

| Possible effects | Biochemical changes | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | Cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias | |

| CNS | Intoxication | Raised blood alcohol |

| Dementia | Decreased thiamine levels | |

| Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome | ||

| Gastric | Gastritis | |

| Haematological | Pancytopenia | Reduced haemoglobin |

| Immune defect | Reduced platelet count | |

| Leukopenia | ||

| Macrocytosis | ||

| Reduced blood clotting factors II, VII, IX, X | ||

| Hepatic | Hepatitis | Raised gamma glutamyl |

| Fatty liver (steatosis) | transpeptidase | |

| Cirrhosis | Raised other liver enzymes | |

| Raised bilirubin | ||

| Reduced albumin | ||

| Intestinal | Malabsorption of glucose and vitamins | Reduced folate, thiamine and vitamins B12, A, D, E and K |

| Oesophageal | Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | |

| Mallory–Weiss syndrome (tears from vomiting) | ||

| Pancreatic | Pancreatitis | Raised serum amylase |

Diagnosis

▪ Gamma glutamyl transpeptidase increased ▪ Complete blood count (macrocytosis often without anaemia) ▪ Blood alcohol levels raised.

Treatment

▪ Cognitive therapy ▪ Naltrexone ▪ Acamprosate ▪ High-protein, high-calorie and low-sodium diet (± vitamin supplementation).

Prognosis

The high mortality rate in alcoholism is mainly as a result of road traffic accidents and assaults. After a large alcoholic binge, suppression of protective reflexes, such as the cough reflex, can result in inhalation of vomit, and death.

▪ Mortality related to alcoholic hepatitis diagnosis is 10-25%, and life quality and expectancy can be affected by diseases including: • liver disease, especially alcohol-induced hepatitis and cirrhosis • nutritional defects • pancreatitis • gastritis and peptic ulcer • immune defects leading to infections, especially pneumonia and tuberculosis, and impaired wound healing • cardiomyopathy • myopathy • brain damage and epilepsy.

▪ Social difficulties from alcohol misuse can affect the six “Ls”: • law – breach of the criminal, civil and/or professional codes • learning – intellectual difficulties • livelihood – job problems • living – housing problems • lover – interpersonal difficulties of all kinds, husband/wife, partner, employer/employee etc. • lucre (Latin – lucrum = wealth) – money problems.

Oral findings

▪ The most common oral effect of alcoholism is neglect, leading to advanced caries and periodontal disease ▪ Dental erosion may result from regurgitation ▪ Nocturnal bruxism by reticular system stimulation is common, and may predispose to temporomandibular joint disorders ▪ If there is deficiency of folate or other B complex vitamins (niacin, piridoxine, riboflavine or thiamine), sore mouth, recurrent aphthae, glossitis, dysgeusia, tongue depapillation, dysaesthesia and angular stomatitis may result ▪ Painless, bilateral, parotid gland enlargement due to fat infiltration (sialosis) is frequent in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis ▪ Other orofacial features include a smell of alcohol on the breath, telangiectases and possibly rhinophyma (enlargement of the nose with dilation of follicles and redness and prominent vascularity of the skin, also known as “grog blossom”).

Dental management

Risk assessment

The main relevant medical complications are related to liver cirrhosis, which may delay the metabolism of many drugs, and also result in a bleeding tendency. Problems obtaining valid consent may arise, particularly if the patient is intoxicated.

Preventive dentistry and patient education

▪ Dentists should screen for alcohol abuse by recognising characteristic clinical and laboratory findings and behavioural disturbances ▪ Alcohol is a known risk factor for oral cancer development, thus a periodical examination for detection of suspicious soft-tissue lesions is mandatory ▪ Dentists should provide specific preventive information to patients with alcoholism and refer them to health care providers for assessment or treatment ▪ Oral health care advice should be given ▪ Diet counselling should be provided.

Pain and anxiety control

Local anaesthesia

Tolerance to local anaesthetics (LA) has been described, especially in long-term alcohol abusers. Even with larger than normal doses, the efficacy and duration of LA can be limited.

Conscious sedation

Sedatives (including benzodiazepines) or hypnotics generally have an additive effect with alcohol, although these interactions are not entirely predictable. Heavy drinkers, however, may become tolerant not only of alcohol but also of other sedatives. Once liver disease develops the position is reversed and drug metabolism is impaired – drugs then have a disproportionately greater effect

General anaesthesia

Alcoholics are also notoriously resistant to general anaesthesia (GA). Heavy drinkers are especially prone to aspiration lung abscess. GA may also be contraindicated in patients with alcoholic heart disease, hypoalbuminaemia or severe anaemia. In consequence, GA is best avoided.

Patient access and positioning

Alcoholics are best given a morning appointment, when they are least likely to be under the influence of alcohol. Erratic attendance for dental treatment is not uncommon. Appointments should be for longer if local anaesthetic tolerance is anticipated.

Treatment modification

Because of erratic attendance, and neglect of caries and periodontal disease, only simple restorative procedures should be planned. Consent issues may arise if the patient is intoxicated, particularly if Wernicke's encephalopathy or Korsakoff's syndrome is also present. Careful consideration of the patient's ability to understand and weigh up the information provided is needed, and consent may not be valid on subsequent appointments if the patient is unable to remember the discussion. If available, an escort is desirable as this may improve patient attendance and improve discharge arrangements and care.

Surgery

Two of the most important complications of excessive alcohol intake are maxillofacial trauma and head injuries. Care should be taken when surgery is contemplated, as liver disease causes a bleeding tendency due to a reduction in blood coagulation factors, and some patients may also have thrombocytopenia. Wound healing may be impaired in the severe chronic alcoholic. Indeed, in a series reported in the USA, alcoholism was found to be a common factor in patients with osteomyelitis following jaw fractures. Before providing treatment, laboratory tests including full blood cell count, liver enzyme levels and coagulation screening should be performed and a physician consulted.

Table 3.5.

Key considerations for dental management in alcoholism (see text)

| Management modifications* | Comments/possible complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk assessment | 2 | Liver cirrhosis, consent |

| Preventive dentistry and education | 1 | Alcoholism screening, oral cancer screening and diet counselling |

| Pain and anxiety control | ||

| – Local anaesthesia | 1 | Tolerance |

| – Conscious sedation | 1 | Additive effect |

| – General anaesthesia | 5 | Resistance, aspiration |

| Patient access and positioning | ||

| – Access to dental office | 0 | |

| – Timing of treatment | 1 | Morning |

| – Patient positioning | 0 | |

| Treatment modification | ||

| – Oral surgery | 1 | Bleeding tendency |

| – Implantology | 5 | Poor risk group |

| – Conservative/Endodontics | 1 | Maintenance compromised |

| – Fixed prosthetics | 1 | Maintenance compromised |

| – Removable prosthetics | 0 | |

| – Non-surgical periodontology | 1 | Maintenance compromised |

| – Surgical periodontology | 1 | Bleeding tendency |

| Hazardous and contraindicated drugs | 2 | Sedatives, NSAIDs, metronidazole, cephalosporins |

0 = No special considerations. 1 = Caution advised. 2 = Specialised medical advice recommended in some cases. 3 = Specialised medical advice mandatory. 4 = Only to be performed in hospital environment. 5 = Should be avoided.

Implantology

Although there is no direct evidence that alcoholism is a contraindication to implants, such patients may not be a good risk group, because of neglected oral health, tobacco smoking, bleeding problems, and osteoporosis.

Periodontology

It is important to avoid any alcohol-containing preparations, such as some antimicrobial and antiplaque mouthwashes. Maintenance by the patient will be often compromised and this has to be considered before planning periodontal treatment.

Drug use

▪ Diazepam, lorazepam and other sedatives increase CNS depression ▪ Aspirin should be avoided since it is more likely in the alcoholic patient to cause gastric erosions and bleeding, and to precipitate bleeding. The hepatotoxic effects of acetaminophen/paracetamol are enhanced, although it is still probably the safest analgesic in this group, and may be used in reduced dosage. ▪ Metronidazole and cephalosporins can interact with alcohol to cause widespread vasodilatation, nausea, vomiting, sweating, headache and palpitations similar to the antabuse reaction (disulfiram effect). The effects are unpleasant or alarming but rarely dangerous.

Further reading

- van der Bijl P. Substance abuse – concerns in dentistry: an overview. S Afr Dent J. 2003;58:382–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander AH, Marder SR, Pisegna JR, Yagiela JA. Alcohol abuse and dependence: psychopathology, medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:731–740. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

Definition

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, which causes loss of cognitive and motor functions. It represents the main cause of dementia, especially in patients over 65 years of age.

General aspects

▪ Dementia is a chronic organic brain disease characterised by amnesia (especially for recent events), inability to concentrate, disorientation in time, place or person and intellectual impairment (including loss of normal social awareness) ▪ It has many causes (Table 3.6 ), the most common being: • Alzheimer's disease • multi-infarct (vascular) dementia • Lewy body dementia ▪ Dementia is usually seen in old age, and may be mimicked by acute organic brain disease, confusional states, drug-induced disorders and psychiatric disease.

Table 3.6.

Causes of dementia

| Common causes | Uncommon causes |

|---|---|

| Alcoholism | AIDS |

| Alzheimer's disease (>60% of all dementia) | Brain trauma, haemorrhage or infection |

| Cortical Lewy body dementia (10%) | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| Huntington's chorea | Metabolic causes (e.g. hypothyroidism) |

| Hydrocephalus | Pick's disease (frontal lobar atrophy) |

| Multi-infarct dementia (25%) | |

| Tumours | |

Aetiopathogenesis

Cortical atrophy and consequent ventricular enlargement are present, probably related to deficiency of acetylcholine and other brain neurotransmitters. Suggested risk factors include: ▪ gene defects (20% of cases) ▪ apolipoprotein-Epsilon 4 (apoE4) ▪ insulin resistance ▪ herpes virus infection ▪ others (cerebral ischaemia, immunological disturbances, etc).

Clinical presentation

▪ First stage: • memory loss • disorientation in time and place • judgment impaired • lack of spontaneity • poor appearance ▪ Second stage: • loss of intellect • aphasia • inability to feed or clothe self • acquired defects of visual–spatial skill ▪ Third stage: • apathy and mutism • inability to communicate • anxiety, depression, irritability • hyperorality • hyper-reflexia • absolute dependence • disruptive behaviour may be present.

Diagnosis

A definitive diagnosis can only be made at autopsy. However the following allow a working diagnosis to be made: ▪ History and clinical findings: • development of multiple cognitive disturbances • memory impairment • problems with language (aphasia), motor activities (apraxia), recognition (agnosia), planning, organisation ▪ Neuropsychiatric tests ▪ Neuroimaging (cortical atrophy and ventricular enlargement).

Treatment

▪ Rivastigmine ▪ Donepezil ▪ Galantamine ▪ Aspirin and gingko biloba may delay onset.

Prognosis

Patients need increasing support as they become progressively more helpless. At the end stage of their disease, they may become bed-ridden and require nasogastric feeding; they often succumb to aspiration pneumonia or secondary infection.

Oral findings

▪ Oral hygiene neglect typically increases with Alzheimer's disease progression ▪ Xerostomia, due to poor saliva production and drugs (phenothiazines), gives rise to candidosis, cervical caries and prosthesis intolerance ▪ Periodontal disease is common, as is halitosis ▪ Loss of taste ▪ Depapillated, red, dry, fissured tongue ▪ Trauma due to apraxia is not unusual, and may present with: • maxillofacial injuries • traumatic oral ulcers • missing and broken teeth • attrition • severe alveolar ridge atrophy secondary to ill-fitting dentures ▪ Oral dyskinesia due to antipsychotic medication.

Dental management

Studies have shown that about 75% of patients with Alzheimer's disease need dental attention. The stage of the Alzheimer's disease and the complexity of the dental treatment will decide if the patient can be treated in the dental clinic, at hospital or at home (bed-ridden). Comprehensive oral rehabilitation is best completed as early as possible since the patient's ability to cooperate during dental treatment diminishes with advancing disease. If long-term care is anticipated, full mouth diagnostic radiographs should be taken and kept for future use. In dentate patients, fabrication of custom mouthguards for fluoride treatment facilitates long-term fluoride therapy, but many people with advanced disease will not tolerate this. The best alternative is more frequent recall visits including prophylaxis and application of topical fluoride. Informed consent is a complex issue in all patients with dementia and requires consultation with the patient's physician.

Risk assessment

The patient with Alzheimer's disease may be relatively healthy or may have accumulated a host of additional systemic diseases, but the chief problems are behavioural. Consultation with the patient's physician is recommended.

Preventive dentistry

It is crucial to anticipate the future decline in oral hygiene due to progressive loss of motor and cognitive skills. When the patient is unable to undertake oral care effectively, it is important to involve and educate family, partners and care providers. Electric tooth brushing with use of chlorhexidine (mouthwash, gel or spray) may be helpful.

Pain and anxiety control

Local anaesthesia

The patient may accept treatment under local analgesia in the early stages of disease, but will need progressively more assistance.

Conscious sedation

Preoperative sedation with a short-acting benzodiazepine may be required. Nitrous oxide sedation may also be useful.

General anaesthesia

In patients with loss of ability to cooperate or those with hostile behaviour, general anaesthesia may be required.

Patient access and positioning

Access to dental surgery

With progressive disease, access may be significantly compromised. Escorts and/or domiciliary care are often required. Medications such as antidepressants administered to patients with Alzheimer's have been shownto increase the incidence of hip fracture, further restricting access.

Timing of treatment

Dental appointments and instructions are often forgotten unless a carer/family member is also involved. Treatment should, as far as possible, be carried out in the morning, when cooperation tends to be best. The usual carers should be present, and treatment undertaken in a familiar environment, with time allowed to explain every procedure before it is carried out. Time-consuming and complex treatments should be avoided.

Patient positioning

Particularly in the end stages of diseases, the patient should be treated sitting upright in the dental chair or slightly reclined, in order to avoid aspiration and postural hypotension.

Treatment modification

Whilst it is still possible to provide dental treatment, it should be planned with the knowledge that the patient will sooner or later become unmanageable for treatment under local analgesia. Later, there is progressive neglect of oral health as a result of forgetting the need or even how to brush the teeth or clean dentures. Dentures are also frequently lost or broken or cannot be inserted or tolerated. Complex dental treatment such as dental implants, which require follow-up and meticulous oral hygiene, are not indicated.

Table 3.7.

Key considerations for dental management in Alzheimer's disease (see text)

| Management modifications* | Comments/possible complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk assessment | 2 | Behaviour control; other systemic diseases; consent |

| Preventive dentistry | 1 | Electric toothbrushing; chlorhexidine |

| Pain and anxiety control | ||

| – Local anaesthesia | 1 | Behaviour control; |

| – Conscious sedation | 1 | other systemic diseases |

| – General anaesthesia | 3/4 | |

| Patient access and positioning | ||

| – Access to dental office | 1 | Hip fracture |

| – Timing of treatment | 1 | Morning; carer present |

| – Patient positioning | 1 | Sitting upright |

| Treatment modification | ||

| – Oral surgery | 1 | |

| – Implantology | 5 | Poor oral hygiene |

| – Conservative/Endodontics | 1 | Single procedures |

| – Fixed prosthetics | 1 | Single procedures, early stages |

| – Removable prosthetics | 1/5 | Lost, broken, poorly tolerated |

| – Non-surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| – Surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| Hazardous and contraindicated drugs | 2 | Tolerance of sedatives |

0 = No special considerations. 1 = Caution advised. 2 = Specialised medical advice recommended in some cases. 3 = Specialised medical advice mandatory. 4 = Only to be performed in hospital environment. 5 = Should be avoided.

Drug use

Regular use of sedatives can lead to tolerances, addiction, and cognitive impairment.

Further reading

- Henry R, Smith B. Treating the Alzheimer's patient. A guide for dental professionals. J Mich Dent Assoc. 2004;86:32–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel H. Alzheimer's disease and oral care. Dent Update. 2004;31:273–278. doi: 10.12968/denu.2004.31.5.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocaelli H, Yaltirik M, Yargic LI, Ozbas H. Alzheimer's disease and dental management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:521–524. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.123538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

AMPHETAMINE, LSD AND ECSTASY ABUSE

Definition

Stimulants are drugs that enhance brain activity, increasing alertness and attention and heightening awareness.

General aspects

The most common drugs of misuse are amphetamines, LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) and ecstasy (MDMA – 3,4-methylene-dioxymethamphetamine).

▪ Dextroamphetamine (amphetamine) and methylphenidate are the most representative drugs. Stimulants are prescribed for treating only a few health conditions, including narcolepsy, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and deep depression. Amphetamines are misused or abused for their euphoriant effect, to stave off fatigue in order to continue working and for slimming. ▪ LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), manufactured from lysergic acid (found in ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and other grains), is a major hallucinogen, considered one of the most potent mood-changing chemicals ▪ MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), popularly known as “ecstasy”, is a synthetic, psychoactive drug with sympathomimetic properties, and both stimulant (amphetamine-like) and hallucinogenic (LSD-like) properties.

Pathogenesis

Amphetamines

▪ These are the main drugs in a group of central stimulants which also includes phenmetrazine, methylphenidate and, to a lesser extent, diethylpropion. They produce a range of effects by stimulating alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors, increasing the levels of monoamines (which include norepinephrine and dopamine) and thus stimulating the CNS and peripheral nervous system. ▪ Acute amphetamine toxicity causes dry mouth, dilated pupils, tachycardia, aggression, talkativeness, tachypnoea and hallucinations, leading to seizures, hypertension, hyperpyrexia, arrhythmias and collapse ▪ Chronic amphetamine toxicity causes restlessness, hyperactivity, loss of appetite and weight, tremor, repetitive movements, bruxism and picking at the face and extremities ▪ High doses of amphetamines can cause mood swings and psychoses (including hallucinations and paranoia), and can cause respiratory failure and death ▪ Combining use with other drugs such as alcohol can result in nausea, difficulty breathing and unconsciousness.

LSD

▪ The effects of LSD are unpredictable but prolonged (∼12h), depending on the amount taken, the user's personality, mood, and expectations, and the surroundings in which the drug is used ▪ Typically, LSD produces several different emotions at once or users swing rapidly from one emotion to another within 30-90 minutes. Synaesthesia, the overflow from one sense to another when, for example, colours are heard, is common. There is often lability of mood, panic (“bad trip”) and delusions of magical powers, such as being able to fly. If taken in a large enough dose, the drug produces delusions and visual hallucinations. The user's sense of time and self changes. ▪ Many LSD users experience flashbacks, recurrence of certain aspects of a person's experience, without having taken the drug again. A flashback comes suddenly, often without warning, and may be within a few days or more than a year after LSD use. ▪ The physical effects from LSD are similar to those of catecholamines and include: • dilated pupils • raised body temperature, heart rate and blood pressure • sweating • loss of appetite • sleeplessness • dry mouth • tremors. ▪ Severe adverse effects include terrifying thoughts and feelings and despair, occasionally leading to fatal accidents.

MDMA

▪ MDMA (ecstasy) affects dopamine-containing neurones that use the chemical serotonin to communicate with other neurones; a decrease in serotonin transporters has been recently demonstrated in the brain of MDMA users by positron emission tomography (PET) ▪ Ecstasy, like amphetamines, produces euphoria and appetite suppression, but is more potently hallucinogenic, possibly because of chemical affinities with mescalin. ▪ It is usually taken by mouth, producing effects after 20-60 minutes ▪ Adverse effects of MDMA are not dose-related, and include: • psychiatric sequelae such as agitation or paranoia • neurological effects such as ataxia and seizures • cardiovascular such as tachycardia, arrhythmias or infarction • renal or hepatic failure • other effects ▪ MDMA users face risks similar to those found with the use of cocaine and amphetamines: • psychological difficulties, including confusion, depression, sleep problems, drug craving, severe anxiety, and paranoia – during and sometimes weeks after taking MDMA • physical symptoms such as muscle tension, involuntary teeth clenching, nausea, blurred vision, rapid eye movement, faintness, and chills or sweating • raised heart rate and blood pressure, a special risk for people with circulatory or heart disease ▪ There is evidence that people who develop a rash that looks like acne after using MDMA may be risking severe side effects, including liver damage, if they continue to use the drug.

Clinical presentation

The most significant risks from drug abuse are behavioural disturbances and psychoses. Intravenous use of these drugs is further complicated by the risk of transmission of infections (HIV, hepatitis B), infective endocarditis or septicaemia.

Findings that may indicate a drug addiction problem include: ▪ Work absenteeism, frequent disappearances from the workplace, making improbable excuses and taking frequent or long trips to the toilet or to the stockroom where drugs are kept ▪ Personality change – mood swings, anxiety, depression, lack of impulse control, suicidal thoughts or gestures, and deteriorating interpersonal relations with colleagues and staff; the user rarely admits errors or accepts blame for errors or oversights ▪ Unreliability in keeping appointments, meeting deadlines, and work performance – which alternates between periods of high and low productivity. Many suffer from mistakes made due to inattention, poor judgment, bad decisions, confusion, memory loss, and difficulty concentrating or recalling details and instructions. Ordinary tasks require greater effort and consume more time. ▪ Progressive deterioration in personal appearance and hygiene, and uncharacteristic deterioration of handwriting and charting ▪ Other common signs are: • tachycardia (amphetamines) • hyperpyrexia (ecstasy) • bruxism – amphetamines or ecstasy • drug-associated diseases • psychosis.

Recognition of individuals who may be abusing drugs is critical. Behavioural problems or drug interactions may interfere with dental treatment. Intravenous drug use (IVDU) is associated with the risk of transmission of infections (HIV, hepatitis B), and complications such as infective endocarditis (which will require antibiotic prophylaxis).

Withdrawal and treatment

▪ Amphetamines have no true withdrawal syndrome and, in this respect, amphetamine addiction is quite different from opioid or barbiturate dependence ▪ LSD is not considered an addictive drug since it does not produce compulsive drug-seeking behaviour as do cocaine, amphetamine, heroin, alcohol, and nicotine; most users of LSD voluntarily limit or stop its use over time ▪ After long-term use of ecstasy, tolerance develops but there is neither physical dependence nor withdrawal symptoms.

Oral findings

Amphetamines

▪ Bruxism may result from chronic amphetamine use ▪ There can be xerostomia and greater caries incidence.

MDMA

▪ Jaw clenching appears to be common ▪ Bruxism, TMJ dysfunction, dry mouth, attrition, erosion, mucosal burns or ulceration and periodontitis have been reported.

Ecstasy has been associated with significantly increased wear of the occlusal surfaces of the back teeth, which contrasts to the usual pattern of tooth wear affecting the front teeth. It has been suggested that ingestion of carbonated and acidic beverages during ecstasy use may contribute to this problem.

Dental management

Risk assessment

Care should be taken with any patient who is a known IVDU or who: ▪ has subjective symptoms of dental pain, with no objective evidence of the disorder ▪ makes a self-diagnosis and requests a specific drug, especially a psychoactive agent ▪ appears to have a dramatic but unexpected complaint such as trigeminal neuralgia ▪ firmly rejects treatments that exclude psychoactive drugs ▪ has no interest in the diagnosis or investigations or refuses a second opinion.

Pain and anxiety control

Local anaesthesia

Amphetamines enhance the sympathomimetic effects of epinephrine and thus vasoconstrictors are best avoided, since hypertension and cardiotoxicity can result.

Conscious sedation

CS should be used with great caution due to the potential deleterious effects of amphetamine/LSD/MDMA use (cardiovascular, renal and hepatic). If CS is strongly indicated, it is important to ensure that the patient is not concurrently abusing drugs, and treatment may be best undertaken in a hospital environment. Opioids are contraindicated

General anaesthesia

Amphetamine addicts may be remarkably resistant to GA. Furthermore, if using intravenous drugs, patients may have problems with venous access and many of the infective problems of opioid addicts. Intravenous barbiturates should be avoided because they may induce convulsions, respiratory distress or coma. Opioids are also contraindicated.

Patient access and positioning

Patients are best given a morning appointment, when they are least likely to be under the influence of drugs. Ideally, the patient should be instructed not to use drugs within 12 hours of the appointment. Erratic attendance for dental treatment is not uncommon.

Treatment modification

Consent issues may arise if the patient is under the influence of drugs. If available, an escort is desirable as this may improve patient attendance and improve discharge arrangements and care. The considerations that need to be taken into account when treatment is undertaken depend on the degree of drug abuse and related social, medical and dental complications. Hence each patient must be assessed on an individual basis, as the necessary modification may vary from caution, to the planned procedure being contraindicated. Examples of factors that may compromise care for all types of dental treatment planned include: ▪ social issues, such as availability of escorts, discharge arrangements, financial constraints ▪ medical issues, such as related cardiac, renal or hepatic complications ▪ dental issues, such as degree of dental neglect, degree of xerostomia, concurrent smoking.

Table 3.8.

Key considerations for dental management in amphetamine, LSD or ecstasy abuse (see text)

| Management modifications* | Comments/possible complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk assessment | 2 | Drug abusers recognition; abnormal behaviour; drug interactions; infections with IVDU; consent issues |

| Pain and anxiety control | ||

| – Local anaesthesia | 2 | Avoid epinephrine |

| – Conscious sedation | 3/4 | Avoid opioids |

| – General anaesthesia | 3/4 | Avoid halothane, ketamine, suxamethonium, barbiturates and opioids; resistance to GA |

| Patient access and positioning | ||

| – Access to dental office | 0 | |

| – Timing of treatment | 1 | Morning appointment; 12 hours after last dose; failed appointments |

| – Patient positioning | 0 | |

| Treatment modification | ||

| – Oral surgery | 1 | |

| – Implantology | 1/5 | Neglected oral hygiene; periodontitis; bruxism; xerostomia; heavy smokers |

| – Conservative/Endodontics | 1 | |

| – Fixed prosthetics | 1/5 | Neglected oral hygiene; heavy smokers |

| – Removable prosthetics | 1 | |

| – Non-surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| – Surgical periodontology | 1/5 | Neglected oral hygiene; heavy smokers |

| Hazardous and contraindicated drugs | 1 | Avoid opioids |

0 = No special considerations. 1 = Caution advised. 2 = Specialised medical advice recommended in some cases. 3 = Specialised medical advice mandatory. 4 = Only to be performed in hospital environment. 5 = Should be avoided.

Further reading

- van der Bijl P. Substance abuse – concerns in dentistry: an overview. S Afr Dent J. 2003;58:382–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Clark DB, Weyant R. Dental abnormalities in children of fathers with substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2004;29:979–982. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milosevic A, Agrawal N, Redfearn P, Mair L. The occurrence of toothwear in users of Ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27:283–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler NA. Patients who abuse drugs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:12–14. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.110307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner JW. Caries associated with methamphetamine abuse. J Mich Dent Assoc. 2002;84:42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ANAEMIAS (DEFICIENCY)

Definition

Anaemia is diagnosed when the haemoglobin level falls > 10% from normal concentrations established for age and sex.

General aspects

Aetiopathogenesis

Anaemia is related to: ▪ a decrease in the number of circulating red blood cells, due to: • decreased production • increased red blood cell loss (usually haemorrhage) ▪ or an abnormality in the haemoglobin.

Anaemia is not a disease in itself but a feature of many diseases (Table 3.9 ). The most common cause of anaemia in developed countries is chronic blood loss and consequent iron deficiency. In women, this is normally caused by heavy menstruation, and in men, blood loss is via occult sources (gastrointestinal or genitourinary). Dietary deficiency and malabsorption (post-gastrectomy) may also cause iron deficiency anaemia. Folate and vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency are the next most common causes of anaemia.

Table 3.9.

Main causes and classification of anaemias

| Type of anaemia | Examples |

|---|---|

| Microcytic hypochromic |

|

| Macrocytic |

|

| Normocytic |

|

Clinical presentation

Clinical findings are mainly influenced by the underlying cause, the severity of anaemia and the time it takes to develop (Fig. 3.4 ). In the early stages, anaemia is frequently asymptomatic. The effect of anaemia is to reduce the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and this may eventually lead to dyspnoea and increased cardiac output (palpitations, murmurs, cardiac failure). Most symptoms are thus the consequence of cardiovascular and ventilatory efforts to compensate for oxygen deficiency, and include the following.

Figure 3.4.

Clinical presentation of anaemia

General

Tiredness, anorexia and dyspnoea.

Skin and mucosa

Pallor of the oral mucosa, conjunctiva or palmar creases suggests severe anaemia, although skin colour can be misleading. Splitting and spooning of the nails (koilonychia) may be detected. Sickling disorders may be associated with jaundice.

Cardiovascular

Tachycardia and palpitations. Anaemia also exacerbates, or can cause, heart failure, angina, and the effects of pulmonary disease. Thrombosis occurs in sickling disorders.

Nervous system

Headache and behaviour changes may be seen, and in children there can be learning impairment. Paraesthesia of the fingers and toes and CNS damage (subacute combined degeneration of spinal cord causing loss of joint position and vibration sense and possibly paraplegia) are associated with pernicious anaemia.

Classification

Anaemia is classified on the basis of erythrocyte size as microcytic (small), macrocytic (large) or normocytic (normal size erythrocytes) (Table 3.9).

Microcytic anaemia

(mean corpuscular [cell] volume [MCV] below 78 fL). This is the most common – usually due to iron deficiency, occasionally secondary to thalassaemia or chronic diseases.

Macrocytic anaemia

(MCV more than 99 fL). This is usually caused by vitamin B12 or folate deficiency (not infrequently in alcoholics), sometimes because folate and vitamin B12 are used up in chronic haemolysis, pregnancy or malignancy; and occasionally caused by drugs (methotrexate, azathioprine, cytosine or hydroxycarbamide [hydroxyurea]).

Normocytic anaemia

(MCV between 79 and 98 fL). This may result from a range of chronic diseases including leukaemia, liver disorders, renal failure, infection, malignancy or other causes, particularly sickle cell disease and thalassaemia. Sickle cell disease results from a single amino acid change on both beta chains of haemoglobin (HbSS). It is more common in Africa, followed by India, the Middle East and Southern Europe. Beta thalassaemia mainly occurs in Mediterraneans and reflects at least 100 different genetic defects that result in a deficiency in the number of beta chains of haemoglobin. Only beta thalassaemia major results in severe anaemia, requiring blood transfusions. Alpha thalassaemia is caused by gene deletions on chromosome 11, resulting in a deficiency of one or more alpha chains of haemoglobin. It occurs predominantly in the Far East, Middle East and Africa, and rarely requires blood transfusions.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made from a combination of clinical findings and special tests: ▪ haemoglobin (Hb) assay/complete blood count ▪ mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) and haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) ▪ serum iron and ferritin (iron deficiency anaemia) ▪ serum vitamin B12 and autoantibodies (pernicious anaemia) ▪ red cell folate assays ▪ haemoglobin electrophoresis (haemoglobinopathies).

Treatment

The treatment depends on the underlying cause, e.g.: ▪ iron deficiency anaemia: treat cause and give oral ferrous sulphate ▪ pernicious anaemia: give vitamin B12 by injection for life and/or oral folic acid ▪ folic acid deficiency: give oral folic acid ▪ sickle cell anaemia: splenectomy, folic acid, penicillin, exchange transfusions, chelating agents, pain control ▪ thalassaemia: exchange transfusions, chelating agents, splenectomy.

Prognosis

The prognosis is related to the severity of the underlying disease.

Oral findings

▪ Deficiency anaemias can cause oral lesions such as ulcers, angular stomatitis, sore or burning tongue or glossitis ▪ Hunter's and Moeller glossitis (depapillated sore tongues) and mouth ulcers are seen in pernicious anaemia; oral paraesthesia and dysgeusia are also related to pernicious anaemia ▪ Features described in thalassaemia: • enlargement of maxilla (chipmunk face), due to extramedullary haemopoiesis • migration and spacing of upper anterior teeth • oral ulceration (very rare) • painful swelling of parotids and xerostomia (due to iron deposits) • sore or burning tongue due to folate deficiency • alveolar bone may have a “chickenwire” like radiological appearance • delayed pneumatisation of maxillary sinuses ▪ Features described in sickle cell anaemia: • trigeminal neuropathy due to osteomyelitis • pain due to infarction • radiological features may include: hypercementosis/dense lamina dura, possible hypomineralisation of permanent teeth, apparent mandibular osteoporosis due to bone marrow hyperplasia, skull/diploe thickening with hair-on-end appearance and radio-opacities due to previous infarcts.

Dental management

Risk assessment

The haemoglobin assay/complete blood count should be determined before commencing any dental treatment. In patients with a haemoglobin level below 10 g/dL, caution is advised, and ideally only palliative dental treatment should be undertaken to stabilise the dentition, with perioperative nasal oxygen/pulse oximeter recommended.

In an emergency, anaemia can be corrected by whole blood transfusion, but this should only be given to a young and otherwise fit patient. Packed red cells avoid the risk of fluid overload and can be given in emergency to the elderly patient or those with incipient cardiac failure. A diuretic given at the same time further reduces the risk of congestive cardiac failure. The patient should be stabilised at least 24 hours preoperatively and it should be noted that haemoglobin estimations are unreliable for 12 hours post-transfusion or after acute blood loss.

Specific considerations for individuals with sickle cell anaemia include:▪ treat infections thoroughly to avoid crises ▪ postoperative antibiotics for all surgical procedures ▪ prophylactic antibiotics for post-splenectomy patients.

Specific considerations for individuals with thalassaemia, particularly beta thalassaemia major, include: ▪ recurrent exchange transfusions, with the risk of carriage of hepatitis B, C, G viruses, possible HIV and TTV ▪ cardiomyopathy ▪ splenectomy implications.

Pain and anxiety control

Conscious sedation

Light sedation with benzodiazepines may be undertaken, although oxygen saturation must be carefully monitored. Nitrous oxide is contraindicated in vitamin B12 deficiency, since it interferes with B12 metabolism.

General anaesthesia

The main danger in anaemias is when a GA is given, as it is vital to ensure full oxygenation. Elective operations under GA should not usually be carried out when the haemoglobin is less than 10 g/dL (male).

Patient access and positioning

Short appointments in the morning are recommended to ensure that the patient is not too fatigued. In those patients receiving regular exchange/blood transfusions, it is best to avoid treatment on the same day.

Treatment modification

Surgery

In patients with aplastic anaemia, elective surgery is contraindicated. In emergencies, platelets and antimicrobial cover may be required.

Removable prosthetics

In iron deficiency and pernicious anaemia patients with sore mouth, prostheses may not be tolerated.

Table 3.10.

Key considerations for dental management in deficiency anaemias (see text)

| Management modifications* | Comments/possible complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk assessment | 2 | Haemoglobin assay |

| Cardiac failure | ||

| Pain and anxiety control | ||

| – Local anaesthesia | 0 | |

| – Conscious sedation | 1 | |

| Avoid nitrous oxide in B12 deficiency | ||

| – General anaesthesia | 3/4 | Avoid if haemoglobin is less than 10 g/dL |

| Patient access and positioning | ||

| – Access to dental office | 0 | |

| – Timing of treatment | 1 | If severe anaemia, morning; short appts |

| – Patient positioning | 0 | |

| Treatment modification | ||

| – Oral surgery | 2/4 | Haemoglobin level |

| – Implantology | 3/5 | Avoid in aplastic anaemia; haemoglobin level |

| – Conservative/Endodontics | 1 | |

| – Fixed prosthetics | 1 | |

| – Removable prosthetics | 1 | May be poorly tolerated |

| – Non-surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| – Surgical periodontology | 2/5 | Avoid in aplastic anaemia |

| Hazardous and contraindicated drugs | 1 | Avoid drugs associated with haemolysis |

0 = No special considerations. 1 = Caution advised. 2 = Specialised medical advice recommended in some cases. 3 = Specialised medical advice mandatory. 4 = Only to be performed in hospital environment. 5 = Should be avoided.

Periodontology

In patients with aplastic anaemia, periodontal and mucogingival surgery are contraindicated.

Drug use

Acetaminophen plus codeine is recommended for pain control. In individuals with sickle cell disease: ▪ avoid prilocaine – causes methaemoglobinaemia ▪ avoid drugs likely to cause haemolysis ▪ avoid high dose aspirin (risk of inducing acidosis).

Further reading

- Terezhalmy GT, Moore WS. Pallor. Quintessence Int. 2003;34:642–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

Definition

Ankylosing spondylitis is a seronegative spondyloarthropathy predominantly affecting the spine and sacroiliac joints, mainly in young males.

General aspects

Aetiopathogenesis

▪ It is partly genetically determined: the family history may be positive, and over 90% of patients are HLA-B27 ▪ Inflammation involves the insertions of ligaments and tendons and is followed by ossification forming bony bridges, which fuse adjacent vertebral bodies or other joints.

Clinical presentation

▪ The onset is usually insidious, with low back pain (spondylitis) and stiffness followed by worsening pain and tenderness in the sacro-iliac region due to sacro-iliitis. Hip joints may also be involved ▪ Slowly, the back becomes fixed in extreme flexion, chest expansion becomes limited and respiration impaired (Fig. 3.5 ) ▪ About 25% of those affected develop eye lesions (uveitis or iridocyclitis) ▪ About 10% develop cardiac disease (aortic incompetence or conduction defects).

Figure 3.5.

Clinical presentation of ankylosing spondylitis

Diagnosis

There is no specific diagnostic test but the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is raised and HLA-B27 is often positive. Radiography shows progressive squaring-off of vertebrae (which become rectangular), intervertebral ossification producing a bamboo spine appearance, calcification of tendon/ligament insertions (enthesitis) and obliteration of the sacro-iliac joints.

Treatment

▪ Physiotherapy and exercises ▪ Anti-inflammatory analgesics ▪ Rarely, spine radiotherapy (carries the risk of leukaemia) ▪ Surgery is a final option (rarely indicated).

Prognosis

Patients with early diagnosis and adequate management have a good prognosis. In rare cases of severe and progressive disease, there can be joint deformity, refractory iritis and secondary amyloidosis.

Oral findings

The temporomandibular joints are involved in about 10% of cases, especially in those over 40 years of age with widespread disease. This results in restricted mandibular opening and muscle tenderness, but symptoms are usually mild.

Dental management

Risk assessment

Patients may have aortic valve disease – when antibiotic prophylaxis against endocarditis should be considered. Chronic intake of anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. indometacin or ibuprofen) may produce bone marrow depression, which can cause a bleeding tendency and immune defect and thus the need for antibiotic prophylaxis.

Pain and anxiety control

Local anaesthesia

Ankylosing spondylitis does not affect the selection of LA, although access may be compromised due to limited mouth opening.

Conscious sedation

There are no contraindications regarding the use of CS, although oxygen saturation should be carefully monitored where there is impaired respiratory exchange due to spinal deformity.

General anaesthesia

GA can be hazardous because of severely restricted opening of the mouth, impaired respiratory exchange associated with severe spinal deformity, or cardiac disease (aortic insufficiency).

Patient access and positioning

Cushions and adapted head supports may be required if the patient's neck may be fixed in flexion. It may be best to keep the patient largely upright if the spinal deformity has resulted in breathing problems.

Treatment modification

Surgical treatment may require antibiotic prophylaxis if there is any aortic valve disease. Furthermore, the extent and complexity of treatment offered may have to be limited if access may be compromised due to limited mouth opening and/or spinal deformity.

Table 3.11.

Key considerations for dental management in ankylosing spondylitis (see text)

| Management modifications* | Comments/possible complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk assessment | 2 | Aortic valve disease; bone marrow depression |

| Pain and anxiety control | ||

| – Local anaesthesia | 1 | |

| – Conscious sedation | 1 | |

| – General anaesthesia | 3–5 | Limited mouth opening; restricted chest expansion; cardiac disease |

| Patient access and positioning | ||

| – Access to dental office | 0 | |

| – Timing of treatment | 0 | |

| – Patient positioning | 1 | Neck may be fixed in flexion |

| Treatment modification | ||

| – Oral surgery | 1 | |

| – Implantology | 1 | |

| – Conservative/Endodontics | 0 | |

| – Fixed prosthetics | 0 | |

| – Removable prosthetics | 0 | |

| – Non-surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| – Surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| Hazardous and contraindicated drugs | 0 | |

0 = No special considerations. 1 = Caution advised. 2 = Specialised medical advice recommended in some cases. 3 = Specialised medical advice mandatory. 4 = Only to be performed in hospital environment. 5 = Should be avoided.

Further reading

- Hill CM. Death following dental clearance in a patient suffering from ankylosing spondylitis – a case report with discussion on management of such problems. Br J Oral Surg. 1980;18:73–76. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(80)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenneberg B, Kopp S. Clinical findings in the stomatognathic system in ankylosing spondylitis. Scand J Dent Res. 1982;90:373–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1982.tb00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ANXIETY STATES

Definition

Anxiety has been defined as emotional pain or a feeling of impending danger. Anxiety disorders are extremely common and have a common theme of excessive, irrational fear and dread.

General aspects

Anxiety is common in persons who are emotionally stressed, and may also be associated with systemic diseases (hyperthyroidism; mitral valve prolapse) or psychiatric disorders.

Aetiopathogenesis

The aetiopathogenesis of anxiety remains unclear, but a role for the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) has been suggested. Benzodiazepines block GABA and have been found to be effective anxiolytics. Anxiety can be generated by dental or medical appointments, even amongst most normal patients. Indeed, 65% of all patients report some level of fear of dental treatment.

Clinical presentation

Clinical findings are related to autonomic nervous system hyperactivity and include sweating, increased heart rate, dilated pupils, muscle tension, diarrhoea, polyuria and insomnia (Table 3.12 ).

Table 3.12.

Some possible effects of mild, acute and chronic stress

| Mild | Acute | Chronic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | Mood change | Increased concentration and clarity of thought | Anxiety, loss of sense of humour, depression, fatigue, headaches, migraines, tremor |

| Cardiovascular | Rise in pulse rate and blood pressure | Improved cardiac output and tissue perfusion |

|

| Respiratory | Increased respiratory rate | Improved ventilation | Cough and asthma |

| Mouth | Slight dryness | Dry mouth | Dry mouth |

| Gastrointestinal | Increased bowel activity | Reduced digestion |

|

| Sexual | Male impotence and female irregular menstruation | Male impotence and female irregular menstruation | Male impotence and female amenorrhoea |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is established by clinical findings. Typical signs of anxiety in the dental clinic include a fearful facial expression, agitation, moving eyes or fingers, continuously questioning and tremor.

Treatment

In general, two types of treatment are available for anxiety disorders – psychotherapy (“talk therapy”) and medication, either of which may be effective. Medications used for treating anxiety disorders include: ▪ anti-anxiety medications such as buspirone or benzodiazepines, which relieve symptoms of anxiety quickly and with few adverse effects, except for drowsiness ▪ beta-blockers, such as propranolol, help reduce physical effects such as tremor ▪ antidepressants, which need to be taken for several weeks before symptoms of anxiety start to fade.

Prognosis

Unlike the mild, brief anxiety caused by a stressful event, anxiety disorders are chronic, relentless, and can grow progressively worse if not treated.

Oral findings

Oral manifestations in chronically anxious people may include: ▪ facial arthromyalgia ▪ atypical facial pain ▪ burning mouth syndrome ▪ dry mouth ▪ lip-chewing ▪ bruxism ▪ cancer phobia.

Other lesions that may develop or worsen in anxious patients include: ▪ aphthae ▪ geographic tongue ▪ lichen planus ▪ TMJ dysfunction.

Dental management

According to the General Dental Council (UK) all dentists have the duty to provide adequate pain and anxiety control. Various physical, chemical and psychological modalities may be used, including behavioural management and pharmacological agents, such as those used to provide effective local anaesthesia, conscious sedation and general anaesthesia. It is important to evaluate every patient on an individual basis to prescribe the appropriate measure. General measures in all anxious patients may include: ▪ initial consultation with the patient in a non-clinical environment ▪ explain the dental plan in detail ▪ start with single simple procedures ▪ provide very effective pain control ▪ tell–show–do ▪ give positive reinforcements.

Risk assessment

Patients may have uncontrollable anxiety (often increased by the dental appointment) and can move or even get up unexpectedly during treatment.

Pain and anxiety control

Local anaesthesia

Some patients have a low pain tolerance.

Conscious sedation

Symptoms such as agitation, tachycardia and dry mouth (caused mainly by sympathetic overactivity), are usually controllable by reassurance and possibly a very mild anxiolytic or sedative such as a low dose of a beta-blocker, buspirone or a short-acting (temazepam) or moderate-acting (lorazepam or diazepam) benzodiazepine – provided the patient is not pregnant and does not drive, operate dangerous machinery or make important decisions for the following 24 hours. Intravenous or intranasal sedation with midazolam, or relative analgesia using nitrous oxide and oxygen, are also useful. Informed consent, written instructions and an escort with appropriate discharge arrangements are essential.

General anaesthesia

Patients requiring complex dental treatment and those uncontrolled with sedation may be treated under GA.

Patient access and positioning

Cancellation of appointments and delay are common and precipitate neglect of oral health. To try and minimise this, the waiting time between visits should be short, and initial appointments made to try and acclimatise the patient.

Treatment modification

Treatment planning may have to be modified depending on the patient's cooperation and the use of behavioural and pharmacological methods of anxiety control.

Drug use

Benzodiazepine metabolism is impaired by azole antifungals and macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin and clarithromycin. Alcohol, antihistamines and barbiturates have additive sedative effects with benzodiazepines.

Table 3.13.

Key considerations for dental management in anxiety states (see text)

| Management modifications* | Comments/possible complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk assessment | 2 | Unexpected movement |

| Pain and anxiety control | ||

| – Local anaesthesia | 1 | Low pain tolerance |

| – Conscious sedation | 1 | Strongly recommended |

| – General anaesthesia | 2–4 | May be indicated |

| Patient access and positioning | ||

| – Access to dental office | 0 | |

| – Timing of treatment | 1 | Appointment cancellation and delay are usual |

| – Patient positioning | 0 | |

| Treatment modification | ||

| – Oral surgery | 1 | |

| – Implantology | 1 | |

| – Conservative/Endodontics | 1 | |

| – Fixed prosthetics | 1 | |

| – Removable prosthetics | 1 | |

| – Non-surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| – Surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| Hazardous and contraindicated drugs | 1 | Benzodiazepine interactions |

0 = No special considerations. 1 = Caution advised. 2 = Specialised medical advice recommended in some cases. 3 = Specialised medical advice mandatory. 4 = Only to be performed in hospital environment. 5 = Should be avoided.

Further reading

- Bare LC, Dundes L. Strategies for combating dental anxiety. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:1172–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TA, Heaton LJ. Fear of dental care: are we making any progress? J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1101–1108. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

AORTIC VALVE DISEASES

AORTIC STENOSIS

Definition

Aortic stenosis (AS) is a narrowing of the aortic valve; this generates an increased pressure in the left ventricle to maintain the blood volume per beat.

General aspects

Aetiopathogenesis

Causes include: ▪ senile calcification ▪ bicuspid valve (usually asymptomatic, even in athletes, but a high risk for infective endocarditis which may be the first clue to the defect) ▪ hypertrophic cardiomyopathy ▪ William's syndrome.

Clinical presentation

Features include angina, dyspnoea, syncope and congestive cardiac failure.

Diagnosis

AS is confirmed by echocardiography, ECG and cardiac catheterisation.

Treatment

Endocarditis prophylaxis is the only requirement for asymptomatic patients. Severe AS necessitates surgical treatment such as percutaneous balloon valvotomy, or commissurotomy, or prosthetic valve replacement.

Prognosis

In symptomatic patients, the mean survival is 5 years. In severe aortic stenosis, sudden death is not uncommon.

AORTIC REGURGITATION (INCOMPETENCE)

Definition

The blood propelled to the aorta during systole returns to the left ventricle during diastole due to a defective aortic valve.

General aspects

Aetiopathogenesis

Causes may include: ▪ congenital defect ▪ rheumatic carditis ▪ infective endocarditis ▪ collagen disorders (Marfan syndrome or Ehlers–Danlos syndrome) ▪ hypertension ▪ arthritides ▪ tertiary syphilis ▪ ankylosing spondylitis.

Clinical presentation

Features may include: ▪ dyspnoea ▪ palpitations ▪ cardiac failure.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on echocardiography, ECG, chest radiograph and cardiac catheterisation.

Treatment

Heart valve replacement/surgical correction by valvotomy, grafts or prosthetic valves is the treatment of choice in moderate or severe regurgitation. Endocarditis prophylaxis should be administered when indicated.

Prognosis

Long-term surgical results are usually successful but the perioperative mortality rate is high.

Dental management

Risk assessment

All patients with aortic valve disease require antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infective endocarditis when undergoing risky procedures. Patients with prosthetic valves are particularly susceptible to infective endocarditis, with an associated high mortality rate. Infection within the first 6 months is rarely of dental origin but usually involves Staphylococcus aureus, and has a mortality of around 60%. Replacement of the diseased valve while the infection is still active, together with vigorous antimicrobial treatment, frequently eradicates the disease.

Patient access and positioning

Timing of treatment

Patients scheduled for cardiac surgery should ideally have excellent oral health established before operation. Elective dental care should be avoided for the first 6 months after cardiac surgery.

Preventive dentistry

Teeth with a reasonable prognosis (shallow caries and minimal periodontal pocketing) should be conserved but those with a poor pulpal or periodontal prognosis are best removed before cardiac surgery, particularly in patients who are to have valve replacement, major surgery for congenital anomalies, or a heart transplant.

Pain and anxiety control

Local anaesthesia

An aspirating syringe should be used to give a local anaesthetic, since epinephrine in the anaesthetic given intravenously may (theoretically) increase hypertension and precipitate arrhythmias. Blood pressure tends to rise during oral surgery under local anaesthesia, and epinephrine theoretically can contribute to this – but this is usually of little practical importance.

Conscious sedation

Conscious sedation requires special care and should be undertaken in a hospital setting.

General anaesthesia

General anaesthesia requires special care. It must be remembered that some patients having heart surgery may postoperatively have a residual lesion that makes them a poor risk for general anaesthesia and a high risk for endocarditis. They may also be on anticoagulants.

Treatment modification

Careful monitoring of patients is required regardless of the procedure planned. A pulse and blood pressure determination before starting the dental procedure is mandatory to avoid false alarms. Patients with severe aortic stenosis have reduced pulse and systolic blood pressure. Patients with severe aortic regurgitation have increased differential blood pressure and high systolic blood pressure. Perioperative use of a cardiac monitor may be considered.

Drug use

Most patients are on anticoagulant treatment; those who have received a heart transplant are taking immunosuppressant drugs.

Table 3.14.

Key considerations for dental management in aortic valve disease (see text)

| Management modifications* | Comments/possible complications | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk assessment | 2 | Infective endocarditis; antibiotic prophylaxis |

| Preventive dentistry and education | Thorough assessment; stabilisation essential to minimise risk of infective endocarditis | |

| Pain and anxiety control | ||

| – Local anaesthesia | 1 | Aspirating syringe |

| – Conscious sedation | 3/4 | |

| – General anaesthesia | 3/4 | |

| Patient access and positioning | ||

| – Access to dental office | 0 | |

| – Timing of treatment | 1 | Delay 6 months after cardiac surgery |

| – Patient positioning | 0 | |

| Treatment modification | ||

| – Oral surgery | 1 | Monitor pulse and blood pressure |

| – Implantology | 1 | |

| – Conservative/Endodontics | 1 | |

| – Fixed prosthetics | 1 | |

| – Removable prosthetics | 0 | |

| – Non-surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| – Surgical periodontology | 1 | |

| Hazardous and contraindicated drugs | 2 | Some patients are treated with anticoagulants |