Abstract

Background:

Roadside trauma in India is an increasingly significant problem, particularly because of bad roads, irregular road signs, overcrowding, overspeeding, and bad traffic etiquettes. Adequate information on the characteristics of victims, causes of accidents, frequency, vehicles involved, alcohol intake, and outcome of management is essential for understanding and planning for better management.

Aim:

This study aimed to determine the characteristics of trauma (roadside accidents) victims admitted to various trauma centers in India. The purpose of this study is to examine the epidemiology of trauma within a local community in India through data gained from the different emergency centers and to analyze trauma patients to find the predictors that led to the deaths of trauma patients.

Materials and Methods:

The present observational study involved trauma victims over 1-year period in three centers. Demographical details recorded were age, sex, alcohol intake, systolic blood pressure on arrival, respiratory rate, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, the interval between injury and admission, Injury Severity Score (ISS) risk factors, hospital stay, and outcome.

Results:

A total of 2650 injuries were recorded in 2466 patients. The mean age was 42.45 ± 15.7 years, the mean ISS was 13.82 ± 6.2, and the mean GCS was 12.20 ± 4.1. The mean time to admission at different trauma centres was 48.41 ± 172.8 h. The head injury was the most common (29.52%).

Conclusion:

Road side accidents due to overspeeding was the most common cause whereas driving under the effect of alcohol was the second most common cause. Accidents are common because of bad traffic etiquette on Indian roads.

Key Words: Collision, epidemiology, motorcycle injuries, road traffic accident, trauma

INTRODUCTION

In India, 13–15 people die every hour due to an accident. In 2011, about 142,485 people died in road traffic accidents (RTAs) in India, which is the highest ever in the world. Expected future road traffic deaths suggest that the death toll will increase by approximately 66% over the next two decades. It is low in high-income and developed countries of approximately 28%, with an increase in RTA-related death of almost 92% in China and 147% in India.[1] A total of 4,67,044 road accidents have been reported by States and Union Territories (UTs) in the calendar year 2018, claiming 1,51,417 lives and causing injuries to 4,69,418 people.[1] The RTA death rate may increase to approximately 2/10,000 people in developing countries by 2024; however, it will decrease to <1/10,000 in high-income countries. Mortality and morbidities due to road traffic injuries in India are projected to increase by 150% by 2020.[1,2,3] The nature of injuries sustained due to trauma is well understood; however, the causes of injury are less well understood. There are very few studies from developing countries on the epidemiology of trauma and the data is scanty.[3]

RTA-related information was collected from each tertiary care hospital included in the study, which was compiled and analyzed. However, every case of RTA admitted in defense hospital was reported as medico legal. A shocking temperament which was seen is that many of the accident victims do not report about the accident or injury sustained, to the police and try to solve by mutual understanding between both parties. The collection of data by the local police regarding accident was usually incomplete and manipulated as it was collected by untrained individuals that cannot be used in any research purpose to formulate any guidelines. Adequate and reliable information on the characteristics of victims, causes and type of accidents, frequency and severity of injuries, types of vehicles, and outcome of management is essential for understanding and planning is required for the overall management of the trauma epidemic and its prevention.

Now it is high time to create trauma registries, surveillance, and research in trauma. Our study aims to describe the characteristics of trauma patients, risk factors, and their outcome, who were admitted to the trauma centers in a tertiary care hospital in different locations, and to create a database for research purposes.

As there is an increasing incidence of mortality among roadside trauma patients, it is important to analyze its epidemiology to prevent trauma-related morbidity and mortality. The team of authors reviewed the trauma epidemiology prospectively at a different trauma center with equal capabilities in India and evaluated the factors that led to trauma-related deaths.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present observational study was conducted at three centers namely Jalandhar, Guwahati, and Mumbai trauma center simultaneously. The study was conducted after ethics committee permission from each institution (MHJREC-2011-1-2-3). We collected the data for one year to take care of seasonal variation in road accidents. The trauma registration data had been collected since March 01, 2011, to 28 Feb 2012, and 2466 patients were registered. Cases relating to suicide, poisoning, drowning, and burns were excluded from the study. A simple self-explanatory questionnaire were prepared, and data so obtained was analyzed. Patients' demographic details such as age, sex, systolic blood pressure (BP) on arrival/admission, rate of respiration at admission, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score at the time of arrival, hemoglobin, blood group, at the time of admission in the hospital interval from injury to admission to trauma center, specific injury, Injury Severity Score (ISS), and mechanism of injury were noted. History of preexisting comorbidities such as ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic liver disease, and renal disease was also noted. Injured body region was also recorded. As many patients suffer from more than one injury or injury to many body regions involved, patients with head injury combined with other injury were placed under a group called head injury group. Similarly, patients with orthopedic injury combined with other injury were placed under a group called orthoinjury group and orthopedic injury along with head injury called orthoneuro group. Rest of the other multiple injury patients not fitting in these above group were placed together as polytrauma. These groups were created based on the combination of injury because more than 70% of injuries reporting to any trauma center are either head injury with other injury or ortho injury with other injuries. The results of the treatment were recorded and analyzed.

Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS software version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The frequencies for variables were identified using descriptive statistics. Identification of the independent factors and multivariat analysis associated with trauma mortality was obtained through the adjustment of a logistic regression. Pearson's Chi-square tests were used for categorical variable analysis between survivors and nonsurvivors. Student's t-tests, or nonparametric tests when necessary, were applied for quantitative variable analysis. Only the variables associated with mortality that yielded P < 0.5 in the initial analysis were placed into the logistic regression analysis. Confidence intervals 95% and odds ratios were used to estimate the associations with nonsurvivors.

RESULTS

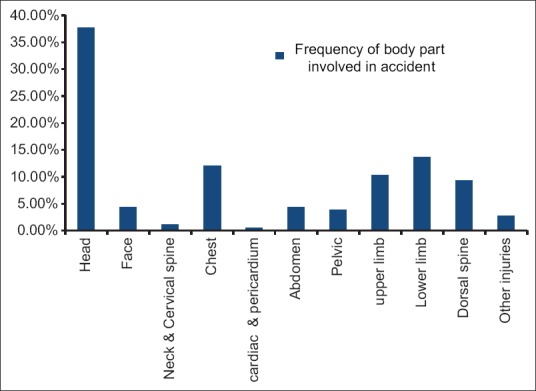

A total of 2650 injuries were recorded in 2466 patients. The mean age of the patients was 28.78 ± 15.29 years. Majority of the patients admitted were among young age group of 14–40 years (75.9%) [Table 1]. Orthopedic, spinal, and head injuries were the most common injuries and affect larger population. Preexisting co morbidities, blood pressure and respiration among trauma victims has been shown in Table 2. Head was the most commonly involved region; among 2466 patients, 1000 patient had head injury (40.5%). The head injury included cerebral contusions, intracranial hematoma, dural hematomas, skull fractures, and cerebral edema. Extremity injuries were the 2nd most frequent (n = 480/2466, i.e., 19.4%). Spinal injuries constituted 14.5% (n = 358), chest injuries with hemothorax constituted 12.8% (n = 318), and abdominal injuries along with head injury constituted 7.7% (n = 190). Mangled forearm (unsalvageable) was found in five patients, in whom amputation was done. Cardiac and pericardium injury was found in 12 patients. The most common injury noted was diffuse axonal injury in 301 patients (11.3%) followed by contusion of the brain (n = 262; 9.8% of injuries). In lower limb, the common fractures were fracture tibia and fibula (n = 119; 4.8%), trochanteric fracture femur (n = 59; 2.3%), distal femur fracture (n = 34; 1.2%), and posterior dislocation of hip (n = 28; 1.0%). Central fracture dislocation of hip and posterior dislocation of hip were common dislocations of hip joint. Lower limb injury constituted 365 patients (13.7%), of which 117 were compound fractures (117/365, i.e., 32.0%) as shown in Table 3a–d.

Table 1.

Distribution of patients by age (n=2466)

| Age (years) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 14-20 | 536 (21.7) |

| 21-30 | 636 (25.7) |

| 31-40 | 701 (28.4) |

| 41-50 | 379 (15.3) |

| 51-60 | 166 (6.7) |

| >60 | 48 (1.9) |

| Total | 2466 |

Table 2.

Preexisting conditions and type of injury

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Preexisting comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 394 (15.9) |

| IHD | 190 (7.7) |

| DM | 689 (27.9) |

| CKD | 131 (5.3) |

| CLD | 98 (3.9) |

| BP | |

| Systolic <90/80 | 982 (39.8) |

| Diastolic <60 | 561 (22.7) |

| Respiratory rate | |

| <15 | 317 (12.8) |

| 15-25 | 1984 (80.4) |

| >30 | 165 (6.6) |

| Type of injury (total n=2650 in 2466 patients) | Number of patients, n (%) |

| Isolated head injury | 309 (12.5) |

| Head injury with major bone fracture | 312 (12.6) |

| Head injury with an abdominal injury | 190 (7.7) |

| Head injury with pelvic injury | 189 (7.6) |

| Chest injury with lung contusion/heamothorax | 318 (12.8) |

| Cervical spine injury, neurologically intact | 89 (3.6) |

| Cervical spine injury with quadriplegia | 21 (0.8) |

| Dorsal lumbar spine injury with neurological intact | 219 (8.8) |

| Dorsal lumbar spine injury with paraplegia | 29 (1.1) |

| Extremity fractures | 480 (19.4) |

| Maxillofacial injury | 115 (4.6) |

| Other injury | 144 (5.8) |

| Mangled forearm (unsalvageable) | 5 (0.2) |

| Mangled leg (unsalvageable) | 2 (0.08) |

| Cardiac and pericardium | 12 (0.4) |

| Crush injury - hand and foot | 32 (1.2) |

CKD: Chronic kidney disease, DM: Diabetis mellitus, CLD: Chronic liver disease, IHD: Ischemic heart disease, BP: Blood pressure

Table 3a.

Distribution of the head, face, and neck injuries (n=1145/2650) noted in 2466 patients included in the study

| Body site | Nature of injury | n (%) | Remarks | Final outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head (n = 1000; 37.7%) | Cerebral contusion | 262 (9.8) | 172 multiple | 2 died |

| Extradural hemorrhage | 142 (5.3) | 98 large (EDH) | All improved | |

| Subdural hemorrhage | 90 (3.3) | 42 large (SDH) | All improved | |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 49 (1.8) | Massive hemorrhage in 3 | All improved | |

| Diffuse axonal injury | 301 (11.3) | 6 died | ||

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 87 (3.2) | All 3 died | ||

| Fracture skull | 69 (2.6) | All improved | ||

| Face (n = 115; 4.3%) | Fracture mandible | 24 (0.9) | Fixed with plate | } All improved |

| Maxillofacial injury | 31 (1.1) | Fixed with plate | ||

| Fracture maxilla | 32 (1.2) | Fixed with plate | ||

| Fracture orbital cavity | 28 (1.0) | Fixed with plate | ||

| Neck (n = 30; 1.1%) | Cervical spine injury with no deficit | 19 (0.7) | Fixed with plate | Improved |

| Cervical spine injury with quadriplegia | 21 (0.7) | Fixed with plate | Discharged in quadriplegic state |

EDH: Extradural hematoma, SDH: Subdural hematoma

Table 3d.

Distribution of dorsal spine and other injuries (n=321/2650) noted in 2466 patients included in the study

| Body site | Nature of injury | n (%) | Remarks | Final outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorsal spine injury (n=248; 9.3%) | Dorsal lumbar spine injury with neurologically intact | 219 (8.2) | Improved | |

| Dorsal lumbar spine injury with paraplegia | 29 (1.0) | Discharged in paraplegic state | ||

| Other injuries (n = 73; 2.7%) | Degloving, bruising minor fractures, laceration etc. | 73 (2.0) | All improved |

Table 3b.

Distribution of the chest, cardiac, abdomen, and pelvis injuries (n=546/2650) noted in 2466 patients included in the study

| Body site | Nature of injury | n (%) | Remarks | Final outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest (n = 318; 12.0) | Multiple rib fractures | 62 (2.3) | Minimal collection | } All improved |

| Ribs fractures with hemothorax | 134 (5.5) | 110 - Bilateral hemothorax | ||

| Hemo-pnemothorax | 48 (1.8) | |||

| Lung contusion | 42 (1.5) | |||

| Flail chest | 32 (1.2) | |||

| Cardiac and pericardium (n = 12; 0.45) | Hemopericardium | 12 (0.4) | 2 died in hospital, 10 improved | |

| Abdomen (n=114; 4.3) | Solid organ laceration with hemoperitoneum | 87 (3.2) | 38 - Liver laceration, 42 spleenic injury, 7 renal injury | 4 died, 83 improved |

| Intestinal perforation with hemoperitoneum | 27 (1.0) | |||

| Pelvis (n = 102; 3.8) | Bladder rupture | 27 (1.0) | } All improved | |

| Fracture of iliac bone | 48 (1.8) | |||

| Acetabulum fracture | 27 (1.0) |

Table 3c.

Distribution of lower and upper limb Injuries (n=638/2650) noted in 2466 patients included in study

| Body site | Nature of injury | n (%) | Remarks | Final outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limb n=273 (10.3%) | Fracture around shoulder girdle | 111 (4.1) | 87 Clavicle, 14 scapula | } All improved |

| Fracture humerus shaft | 14 (0.5) | - | ||

| Fracture distal humerus | 35 (1.3) | 23 open fracture | All improved | |

| Fracture Radius/Ulna | 23 (0.8) | - | All improved | |

| Mangled forearm/wrist | 5 (0.1) | Unsalvageable | Amputation | |

| Fracture with vascular injury | 9 (0.3) | Unsalvageable Fracture shaft humerus with Brachial artery injury | Amputation | |

| Crush injury hand | 25 (0.9) | - | All improved | |

| Degloving injury | 51 (1.9) | - | All improved | |

| Lower limb n = 365 (13.7%) | Trochanteric fracture | 59 (2.3) | - | All improved |

| Posterior dislocation hip | 28 (1.0) | - | } All improved | |

| Fracture dislocation hip | 13 (0.4) | - | } All improved | |

| Fracture Femur shaft | 26 (0.9) | 11 open fractures | } All improved | |

| Fracture distal Femur | 34 (1.2) | 12 open fracture | } All improved | |

| Fracture patella | 27 (1.0) | - | All improved | |

| Posterior dislocation knee | 5 (0.18) | - | All improved | |

| Fracture proximal Tibia | 17 (0.64) | - | All improved | |

| Fracture Tibia shaft | 119 (4.8) | 87 open fracture | All improved | |

| Fracture distal Tibia | 11 (0.44) | 7 open fracture | All improved | |

| Floating knee injury | 1 (0.03) | All improved | ||

| Mangled leg & Foot | 2 (0.07) | Unsalvageable | Amputation | |

| Traumatic near total amputation leg/ankle | 4 (0.15) | Unsalvageable | Amputation | |

| Degloving injury | 14 (0.52) | All improved | ||

| Fracture with vascular injury | 5 (0.18) | Fracture with popliteal artery injury | All improved |

All improved All improved

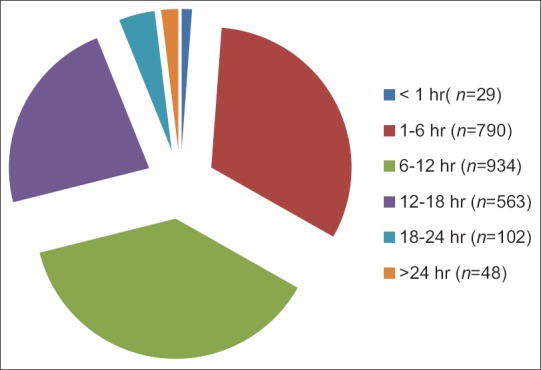

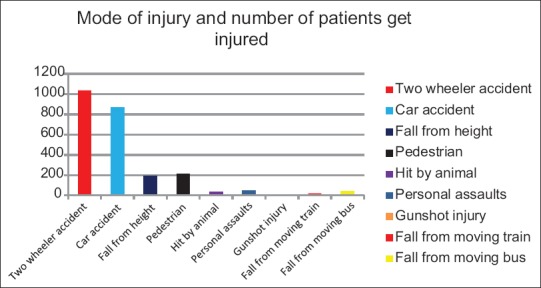

In our study population, 2251 (91.32%) patients were male and 215 (8.71%) were female. The mean interval to the presentation of the injured patient reporting to the hospital was 1.23 ± 1.63 days [Table 4]. Among the injured patients, 790 (32.0%) patients were admitted within 6 h of accident and 934 (37.4%) were admitted within 12 h, while 563 (22.8%) was admitted within 18 h of accident, as shown in Table 4 and Figure 1. Two-wheeler accident (1037 [42.0%]) was the leading cause of the accident as shown in Table 5 and Figure 2.

Table 4.

Time since initial injury and arrival in hospital/admission in hours

| Time (h) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| <1 | 29 (1.17) |

| 1-6 | 790 (32.0) |

| 6-12 | 934 (37.4) |

| 12-18 | 563 (22.8) |

| 18-24 | 102 (4.1) |

| >24 | 48 (1.9) |

| Total | 2466 |

Figure 1.

Time interval between injury and presentation

Table 5.

Distribution of cases by mode of injury (n=2466)

| Mode of injury | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Two-wheeler accident | 1037 (42.0) |

| Car accident | 865 (35) |

| Fall from height | 194 (7.8) |

| Pedestrian | 213 (8.6) |

| Hit by animal | 34 (1.3) |

| Personal assaults | 48 (1.9) |

| Gunshot injury | 11 (0.4) |

| Fall from moving train | 21 (0.8) |

| Fall from moving bus | 43 (1.7) |

| Total | 2466 |

Figure 2.

Distribution of cases by mode of injury

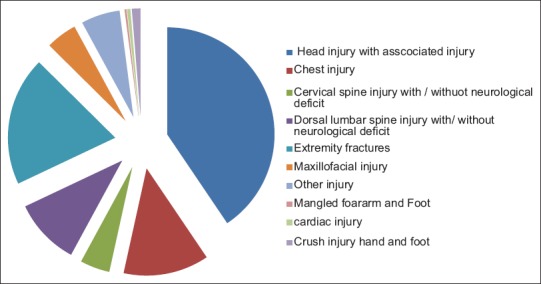

Injury related to alcohol consumption on the part of drivers and the use of mobile phones is depicted in Table 6. The type of injuries has been shown in Figure 3.

Table 6.

Nature of driving faults (with or without helmet, with or without seat belt, and with or without influence of alcohol)

| Nature of fault | n (%) |

|---|---|

| High speed driving car without a seat belt | 402 (16.3) |

| High speed driving car with a seat belt | 241 (9.7) |

| High speed/reckless/rash driving motorbike with a helmet | 194 (7.8) |

| High speed/reckless/rash driving motorbike without a helmet | 213 (8.6) |

| Driving car under the influence of alcohol | 239 (9.6) |

| Driving motorbike under the influence of alcohol | 273 (11.0) |

| Overriding while overspeeding | 190 (7.7) |

| Talking on mobile while driving car | 280 (11.3) |

| Talking on mobile while driving a motorcycle | 235 (9.5) |

| Talking with copassenger while driving a car | 199 (8.0) |

| Total | 2466 |

Figure 3.

Chart showing type of injuries

The mean ISS was 12.67 ± 5.86 (median 8), and the mean GCS was 11.67 ± 5.12 (median GCS 15). Among 2466 patients whose GCS could be recorded, 617 (25.0%) had a score in the range of 5–8 (severe head injury), 341 (13.8%) had a score in the range of 9–12 (moderate); and 1508 (61.11%) had a score range of 13–15 (mild) as shown in Table 7. The frequency of body part involved in accident has been shown in Figure 4.

Table 7.

Patients’ characteristics on arrival/admission

| Variables | Mean±SD | Median |

|---|---|---|

| Patient age | 38.38±16.9 | 33 |

| Time since injury and arrival to hospital (h) | 29.22±171.6 | 6.9 |

| Rate of respiration | 22.22±5.7 | 22 |

| Systolic BP | 89.49±21.79 | 68 |

| ISS | 12.67±5.86 | 8 (n=1089) |

| GCS | 11.67±5.12 | 15 (n=617) |

| Time to a blood transfusion given | 36.12±42.91 | 24 (n=912) |

| Number of a blood transfusion given | 2.34±1.4 | 3 (n=1129) |

| Number of patients needed a blood transfusion | 4.11±2.21 | 486.5 (n=972) (39.4%) |

| Presence of alcohol | 419.12±67.87 | 256.5 (n=512) |

BP: Blood pressure, SD: Standard deviation, GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale, ISS: Injury Severity Score

Figure 4.

Frequency of body part involved in accident

DISCUSSION

In our study population, 2251 (91.32%) patients were male and 215 (8.71%) were female. The mean interval to the presentation of the injured patient reporting to the hospital was 1.23 ± 1.63 days. Among the injured patients 790 (32.0%) patients were admitted within 6 h of accident and 934 (37.4%) were admitted within 12 h, while 563 (22.8%) were admitted within 18 h of accident. The results of the present study are somewhat similar and confirm the finding of others regarding head injuries and skeletal trauma published in the literature.[4,5,6] Traumatic brain injury, especially diffuse axonal injuries, has poor outcome and has high mortality and morbidity.[7] Many patients that died after discharge at home died due to the development of some or other complication and lack of nursing care in a developing country like India. It was also a quite frequent finding that pedestrians are hit by a motorcycle and other vehicles and cause head injuries.[8] Head injury from motorbike injuries occurred mainly among riders who did not wear protective helmets. Many motorbike riders do not use the recommended helmet instead of preferring to use a small cap without a proper strap. In India, the incidence of RTAs is less when a female drives vehicle than a male because women drive carefully and safely.

Spinal cord injury of pedestrians being hit by a speeding vehicle was the most common injury in RTA next to fall from height. However, in a developed country, vehicle head on collision is the most common cause of spinal cord injury.[8,9,10] In India, in rural and even in urban area, lack of railing on roof and proper lights is responsible for the fall of people sleeping on rooftops, especially during summer seasons.

In our study, an alarming and shocking finding of delay in the admission of trauma victim following injury was noted. This may be due to an attitude of apathy among bystanders. Trimodal distribution of death was seen in trauma patients following first mode within seconds to minutes, second mode within hours, and the third phase within days to weeks.[11] If phase-specific intervention was done timely, mortality can be reduced significantly. Primary prevention was observed in the first phase, better transport facilities and care during transport during the second phase, and specific management in the hospital during the third phase.[12] We observed that there was longer waiting time to admission that raises the efficiency on the existing emergency response system. In our study, a total of 514 trauma victims were brought after considerable delay to the hospital by government ambulances because of unavailability of ambulances.

In India, many people are on roads at any given times and among them are pedestrians, bicyclists, and motorcyclists. Cars, scooters, and many heavy motor vehicles are also using the same roads, and the likelihood is higher for accidents to occur in these overcrowded and narrow roads. Results of our study confirm the findings noted by similar published data that have reported a high proportion of deaths on these overcrowding roads.[13,14,15]

However, few studies reported no significant difference in mortality when a trauma victim was directly admitted and referred groups.[16,17,18] However, many authors have reported that immediate transfer (scoop and run) to a tertiary care center lowers mortality among major trauma patients.[19,20,21,22,23] However, this will possible only by introducing awareness in bystanders and first responders, an effective prehospital care, an organized system of triage, dedicated pool of ambulances services and fast easy transport like air evacuation (air ambulances). Bodalal et al.[24] noted that the younger age group (20–29 years of age) formed the majority of RTA cases, while there was a trend toward an increasing average age of patients involved in an accident. In order to reduce mortality and morbidities in accident victim and to prevent road traffic accident, the knowledge of road safety measures like, use of pavements by pedestrians, avoiding reckless and risky driving and wearing of helmet is reqired. Government should insure the easy availability of ambulance which automatically improves prehospital care. Promoting good medical evacuation system, recording system, and government initiative to improve early medical care for trauma victims is required to improve survival rate among polytrauma patients. Further multicentric research including large patient data is required to explore the risk factors that influence the frequency of road accidents in the community in developing countries, especially in India where overcrowding on roads and reckless driving prevails. The length of hospital stay ranged from 2 days to 152 days, with a mean of 24.5 ± 12.2 days. The median was 21.3 days. Hospital stay for nonsurvivors ranged from 1 day to 31 days (mean 6.2 ± 1.3 days and median 5.7 days). The length of intensive care unit stay ranged from 1 day to 39 days (mean = 9.3 ± 3.2 days, median 7.41 days). On multivariate logistic regression analysis, it was clearly shown that patients with severe trauma and those with major bone fractures like femur or tibia stayed longer in the hospital (P < 0.001). Patients with severe trauma, BP < 90 mmHg, and severe head injury (GCS = 3–8) has statistically significantly higher mortality (P < 0.001).

The authors intend to improve treatment and prevent trauma deaths by analyzing the results of treatments and causes of trauma-related deaths. In order to enhance the quality of treatment for severe RTA trauma patients, every local hospital being equipped to take care of these patients, at least initial resuscitation, is concerned. A dedicated ambulance service has been initiated by the Indian government at free of cost for rapid evacuation to the nearest hospital. There is a need for the development of trauma centers, and ambulance service is also required to improve rapid transport. However, immediate stage-wise management, effective damage control, or trauma team management (involving orthopedic surgeon, general surgeons, thoracic and cardiovascular surgeons, and neurosurgeons) is required. In addition, a national trauma registry system is required to study the epidemiology, which results in improvement in trauma care.

We noted high mortality rate when accident takes place in the night and in early morning. It may be because of the lack of streetlights, sleeplessness of driver, and most of the heavy-vehicle drivers were under the influence of alcohol, which made the accidents worse.

Limitation

The limitation of the present study is that the study was carried out at multiple centers with varied traffic congestion, which may affect the evacuation of injured patients to the trauma center. The patients who were expired during cardiac pulmonary resuscitation and those who dead on arrival should have been considered for major trauma outcome. The studies should have taken into consideration autopsy results, hours of surgery, and occupational hazard. All cases of death due to roadside accident were labeled as medico legal, and autopsy was done at a dedicated center designated by the Indian government (district hospitals), however their results were not available on time. This results into failure to establish the exact cause of death. Other limitations such as deaths outside of the hospital such as discharge against advice or death after discharge were not accounted for in this study. Follow-up was not considered in the present study.

CONCLUSION

Road accidents are an epidemic and a constantly increasing health problem in India. The most commonly affected are males and college and university students (young age group). Motorized two wheelers are the offending vehicles in most cases, and those who are affected largely do not use helmet. Driving under the influence of alcohol and overspending are the other common causes of RTA. The government is trying to levy fine on those who do not obey traffic rules such as speed limit, use of safety belts, and helmets, but still, people brake rules, however if combined with better quality roads and roadside illumination, accident scan can be minimized considerably. Public education, a proper prehospital trauma care system, sensitization of bystanders, and definitive trauma care facilities combined with rehabilitation are required for better outcome of trauma victims.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical conduct of research

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board / Ethics Committee. The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network (http://www.equator-network.org/) guidelines during the conduct of this research project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ministry of Road and Transport, Government of India, Total Number of Road Accidents, Persons Killed and Injured during 1970-2012. [Last accessed on 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://morth.nic.in/sites/default/files/Road_Accidednt.pdf .

- 2.Kopits E, Cropper M. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No 3035. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2003. [Last accessed on 2009 Nov 07]. Traffic Fatalities and Economic Growth. Available from: http://www.ntl.bts.gov/lib/24000/24400/24490/25935_wps3035.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menon GR, Gururaj G, Tambe M, Shah B. A multi-sectoral approach to capture information on road traffic injuries. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:305–10. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gururaj G. Background Papers: Burden of Disease in India Equitable Development-Healthy Future. New Delhi: National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005. Injuries in India: A National Perspective; pp. 325–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nwomeh BC, Lowell W, Kable R, Haley K, Ameh EA. History and development of trauma registry: Lessons from developed to developing countries. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:32. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-1-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majdan M, Mauritz W, Brazinova A, Rusnak M, Leitgeb J, Janciak I, et al. Severity and outcome of traumatic brain injuries (TBI) with different causes of injury. Brain Inj. 2011;25:797–805. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.581642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hukkelhoven CW, Steyerberg EW, Habbema JD, Farace E, Marmarou A, Murray GD, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: Development and validation of a prognostic score based on admission characteristics. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:1025–39. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, Butcher I, Lu J, McHugh GS, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: Development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santamariña-Rubio E, Pérez K, Ricart I, Arroyo A, Castellà J, Borrell C. Injury profiles of road traffic deaths. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rochette LM, Conner KA, Smith GA. The contribution of traumatic brain injury to the medical and economic outcomes of motor vehicle-related injuries in Ohio. J Safety Res. 2009;40:353–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rusnak M, Janciak I, Majdan M, Wilbacher I, Mauritz W. Australian Severe TBI Study Investigators. Severe traumatic brain injury in Austria I: Introduction to the study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:23–8. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0760-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trunkey DD. Trauma. Accidental and intentional injuries account for more years of life lost in the U.S. than cancer and heart disease. Among the prescribed remedies are improved preventive efforts, speedier surgery and further research. Sci Am. 1983;249:28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Dass RM, Mbelenge N, Ngayomela IH, Chandika AB, et al. Injury characteristics and outcome of road traffic crash victims at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2012;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1752-2897-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gururaj G. Road traffic deaths, injuries and disabilities in India: Current scenario. Natl Med J India. 2008;21:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohan D. Road traffic injuries and fatalities in India-a modern epidemic. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mishra B, Sinha Mishra ND, Sukhla S, Sinha A. Epidemiological study of road traffic accident cases from Western Nepal. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:115–21. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verma V, Gupta K, Singh GK, Kumar S, Shantanu K, Kumar A. Effect of referral on mortality in trauma victims admitted in trauma centre of Chattrapati Shahuji Maharaj Medical University: A one year follow up study. Hard Tissue. 2014;25:1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balogun JA, Abereoje OK. Pattern of road traffic accident cases in a Nigerian University teaching hospital between 1987 and 1990. J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;95:23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Museru LM, Mcharo CN, Leshabari MT. Road traffic accidents in Tanzania: A ten year epidemiological appraisal. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2002;7:1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampalis JS, Denis R, Lavoie A, Fréchette P, Boukas S, Nikolis A, et al. Trauma care regionalization: A process-outcome evaluation. J Trauma. 1999;46:565–79. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odero W, Garner P, Zwi A. Road traffic injuries in developing countries: A Comprehensive review of epidemiological studies. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:445–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill JR, Mackay GM, Morris AP. Chest and abdominal injuries caused by seat belt loading. Proceedings of the 36th Annual Conference of the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine; Portland: Chicago Association for Advancement of Automotive Medicine; 1992. pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahajan N, Aggarwal M, Raina S, Verma LR, Mazta SR, Gupta BP. Pattern of non-fatal injuries in road traffic crashes in a hilly area: A study from Shimla, North India. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013;3:190–4. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.119198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodalal Z, Bendardaf R, Ambarek M. A study of a decade of road traffic accidents in Benghazi-Libya: 2001 to 2010. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]