Abstract

Introduction

Many low- and middle-income countries have implemented health-system based one stop centres to respond to intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual violence. Despite its growing popularity in low- and middle-income countries and among donors, no studies have systematically reviewed the one stop centre. Using a thematic synthesis approach, this systematic review aims to identify enablers and barriers to implementation of the one stop centre (OSC) model and to achieving its intended results for women survivors of violence in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

We searched PubMed, CINAHL and Embase databases and grey literature using a predetermined search strategy to identify all relevant qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies. Overall, 42 studies were included from 24 low- and middle-income countries. We used a three-stage thematic synthesis methodology to synthesise the qualitative evidence, and we used the CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research) approach to assess confidence in the qualitative research. Meta-analysis could not be performed due heterogeneity in results and outcome measures. Quantitative data are presented by individual study characteristics and outcomes, and key findings are incorporated into the qualitative thematic framework.

Results

The review found 15 barriers with high-confidence evidence and identified seven enablers with moderate-confidence evidence. These include barriers to implementation such as lack of multisectoral staff and private consultation space as well as barriers to achieving the intended result of multisectoral coordination due to fragmented services and unclear responsibilities of implementing partners. There were also differences between enablers and barriers of various OSC models such as the hospital-based OSC, the stand-alone OSC and the NGO-run OSC.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates that there are several barriers that have often prevented the OSC model from being implemented as designed and achieving the intended result of providing high quality, accessible, acceptable, multisectoral care. Existing OSCs will likely require strategic investment to address these specific barriers before they can achieve their ultimate goal of reducing survivor retraumatisation when seeking care. More rigorous and systematic evaluation of the OSC model is needed to better understand whether the OSC model of care is improving support for survivors of IPV and sexual violence.

The systematic review protocol was registered and is available online (PROSPERO: CRD42018083988).

Keywords: health services research, public health, systematic review

Key questions.

What is already known?

Several process evaluations of the one stop centre (OSC) model in low- and middle-income country (LMIC) settings have documented various challenges, enablers and lessons learnt.

Important evaluation findings of OSCs are scattered across the published literature and in unpublished technical reports.

Only one outcome evaluation has been published which reported that the OSC model led to increased short-term utilisation of primary health services.

Despite increasing popularity of the OSC model in LMICs and among funders, no studies have evaluated the effectiveness of the OSC model in meeting survivor needs.

No systematic review or evidence-based synthesis on the OSC model has been performed prior to the present study.

What are the new findings?

The review found 15 high-confidence evidence barriers to implementation of the OSC model and to achieving its intended results. These included barriers to implementation such as staff time constraints and lack of basic medical supplies, which lead to barriers to achieving intended results like accessible care due to long wait times and out-of-pocket fees.

The review also identified seven enablers with moderate-confidence evidence. These included enablers to implementation such as standardised policies and procedures. They also included enablers to achieving intended results, such as regular interagency meetings that facilitated increased multisectoral coordination.

Key questions.

What do the new findings imply?

The results of this review provide essential evidence to guide OSC leadership, funders, policymakers and government officials on specific factors that should be optimised in order for OSCs to be implemented as intended, achieve their intended results and reach their ultimate goal—namely, to reduce victim retraumatisation when seeking care.

These data should be used to prioritise and guide investment, as well as inform more rigorous evaluation of existing OSCs prior to further promotion and scale-up of this model in LMICs.

Introduction

Violence against women (VAW) is associated with harmful health consequences1 2 and is a major public health concern.3 VAW is also a barrier to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 5 on gender equality and women’s empowerment, and Sustainable Development Goal 3 on health.4 The health sector is well situated to respond, as women facing violence are more likely to view health workers as trustworthy for disclosure of abuse and to use a variety of health services, including mental health, emergency department and primary care services when compared with non-abused women.5–8 A variety of one stop centre (OSC) models have emerged over the years that vary in structure and services provided, resulting in discussion as to how the OSC should be defined. For the purpose of this review, the authors defined an OSC model as an interprofessional, health-system based centre that provides survivor-centred health services alongside some combination of social, legal, police and/or shelter services to survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) and/or sexual violence (SV).

The original OSC was developed in a tertiary hospital and aimed to provide acute services to survivors of violence.9 Soon after OSCs were established in Malaysia in 1994, the model was replicated throughout South East Asia and Western Pacific regions.9 10 It has now been widely implemented with donor support in several African countries,11 12 and similar models are emerging in Latin America.13 The majority of OSCs are hospital-based, typically within tertiary care facilities, while others are stand-alone centres that provide basic health services on-site and refer for specialised and emergency services.14 Some OSCs are more strongly linked to the judicial system as in the case of the Thuthutzela centres in South Africa. They may be managed by the government, private sector, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or a combination.14

Rationale for development of the OSC

The development of the OSC model was a response to numerous issues identified by survivors and their advocates when seeking services in traditional (non-integrated) healthcare, police and legal systems. Survivors often need several multidisciplinary services that are scattered in different locations. They frequently need to retell their stories of trauma each time they engage with a different service/sector which can contribute to secondary victimisation. The intended results of the OSC model are to increase accessibility, acceptability, quality and multisectoral coordination of care in order to reach the ultimate goal of reducing survivor retraumatisation when seeking care.15–17

Current evidence of the OSC model

While multiple process evaluations of the OSC model have been performed, no studies have examined the effectiveness of the OSC model.18–51 Only one outcome evaluation has been published, which found that the OSC model led to short-term increased utilisation of primary health services.13 No systematic reviews on the OSC model have been published.

Theory of change of the OSC model

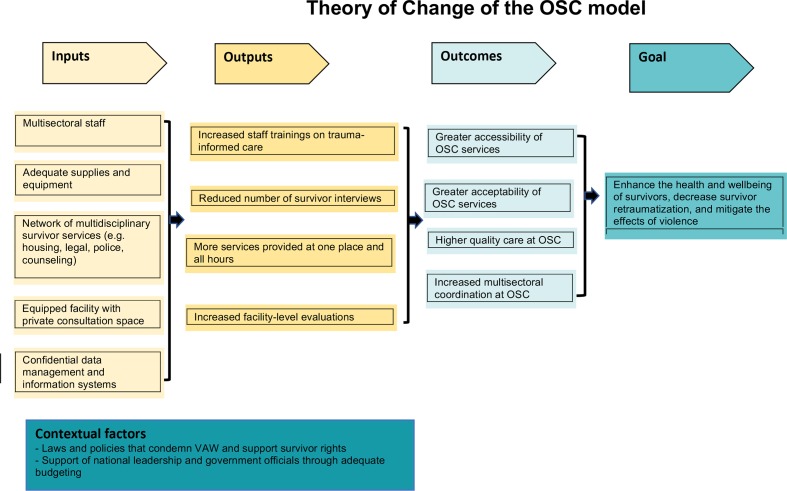

The authors have provided a theory of change for the OSC model to serve as an analytical framework for the study findings (figure 1). The OSC model requires specific inputs such as multidisciplinary staff and private consultation rooms, which contribute to OSC outputs such as more services provided at one location and at all hours, and reduced survivor interviews. These contribute to OSC outcomes such as improved multisectoral coordination and improved quality of survivor-centred care. These outcomes contribute to the ultimate goal of the OSC to reduce survivor revictimisation when seeking care.

Figure 1.

Theory of change of the OSC model.OSC, one stop centre; VAW, violence against women.

Practical rationale of this review

There has been increasing global implementation, scaling-up and donor investment in OSCs, despite a lack of rigorous evaluation of their implementation or their effectiveness. A meeting on this was organised by the WHO in June 2018 where experts discussed current evidence of the OSC model, contextual variations, as well as its strengths and limitations. It was recommended that a systematic review be performed to better assess the barriers and enablers to OSC implementation and achieving its intended results, and to inform a framework for more systematic evaluations of OSCs.

Review objective

Using a thematic synthesis approach, this systematic review aims to identify enablers and barriers to implementation of the OSC model and to achieving its intended results for women survivors of violence in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Patient/survivor experiences, preferences and priorities were sought in every step of the systematic review process. While perspectives of all stakeholders of the OSC model were included in the review, survivor experiences were specially desired and sought after during study selection and data extraction, as it was felt survivors could best inform how implementation of the OSC was affecting its beneficiaries (the survivors) and how the barriers and enablers were perceived to be meeting survivor needs. Patients/survivors themselves were not involved in the design or conduct of this systematic review.

Search strategy

Published literature was searched in PubMed, CINAHL and Embase using controlled vocabulary and free-text terms combining three main search elements: (a) partner violence and/or sexual violence, (b) one stop centre and (c) LMIC. Examples of IPV and/or sexual violence search terms include, ‘Rape’(Mesh) OR ‘Intimate Partner Violence’(Mesh) OR ‘Domestic Violence’(Mesh). Examples of one-stop centre search terms include centre(tiab) OR centre(tiab) OR one stop(tiab) OR stand alone(tiab) OR protection unit(tiab). Full search strategies are available in online supplementary tables S1–3. The third search element was the LMIC context, which was used via the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group LMIC filter (http://epoc.-cochrane.org/lmic-filters). Numerous combinations of these search elements were identified through thesaurus and Medical Subject Headings terms. The following databases were searched for additional studies, including grey literature and unpublished reports: WHO Global Health Library, Cochrane Library, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Google Scholar, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Database, OpenGrey and EThOS. Searches were conducted from 31 June 2018 to 31 December 2018. The search strategies were reviewed by two expert librarians. Numerous researchers in relevant fields were contacted to identify additional published and unpublished studies.

bmjgh-2019-001883supp001.pdf (91.2KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001883supp002.pdf (60.8KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001883supp003.pdf (81.5KB, pdf)

Study selection

All titles and abstracts identified were independently screened using a standardised form (RMO, CG-M). Each full-text article was reviewed by RMO, and in consultation with CG-M, pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (see table 1). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram of search and study inclusion process is provided in online supplementary figure 1. For the purposes of this review, the OSC was defined as any centre that provided integrated, multidisciplinary care to survivors of intimate partner and/or sexual violence with healthcare as a necessary component, as well as two or more additional on-site services, which could include any combination of social, legal and police services. For example, an integrated model that provided legal and police services was not considered an OSC, while a model that provided healthcare, shelter and legal services was considered an OSC. Any discrepancies in the screening were resolved through discussion and consultation with a third author (MC).

Table 1.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Uses quantitative, qualitative or mixed method study designs | Does not present primary research |

| Discusses the OSC model | Not published in English, Spanish or French language |

| Reports barriers and/or enablers of the OSC model | Full text is not available |

| Conducted in LMIC context | Women were not beneficiaries of the OSC (eg, the OSC was only for child survivors) |

LMIC, low- and middle-income country; OSC, one stop centre.

bmjgh-2019-001883supp010.pdf (333.6KB, pdf)

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a standardised form (online supplementary file S1). Themes, participant quotations and findings were extracted from qualitative studies, and where relevant, results and discussion sections of quantitative studies. Results and outcome measures were extracted from quantitative studies. Both types of data were extracted in the case of mixed methods studies.

bmjgh-2019-001883supp004.pdf (73.6KB, pdf)

Synthesis

A thematic synthesis methodology was used to analyse the qualitative data.52 The lead author (RMO) developed a spreadsheet of all qualitative data from the studies’ findings sections, and where relevant, discussion sections. Using the three stage method outlined by Thomas and Harden, 2008, each relevant line of text was openly coded (RMO) through an inductive, line-by-line process to develop first-order themes, which were descriptive and similar in meaning to the primary studies.52 Based on the initial coding, 16 broad themes were developed, and through in iterative process, all text units were classified into one of the broad themes. Each theme was analysed further to develop the axial coding scheme and to disaggregate core themes. The text units were hand-sorted into first-order, second-order and third-order themes whereby axial codes were then systematically applied. Second-order themes were developed by grouping first-level themes together based on similarities and differences. Third-order themes were developed by grouping first-order and second-order themes together based on higher analytical themes.53 Enablers and barriers that emerged from quantitative studies were compared with qualitative themes and when appropriate, incorporated into the thematic analysis. For example, some quantitative studies found that provision of the full course of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) at first encounter improved PEP adherence rates. This result was felt to support the theme, ‘minimisation of points of care facilitates medication adherence’ and thus was referenced under this theme in the mixed method thematic synthesis.

Quality assessment and confidence assessment

The CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research) approach was applied to each review finding to assess confidence in each review finding.54 The CERQual approach assesses how much confidence to place in review findings of qualitative systematic reviews based on: (1) methodological limitations, (2) relevance of the review question, (3) coherence and (4) adequacy of data. Methodological limitations were assessed using two tools: an adaptation of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was used to assess the quality of the qualitative studies,55 and an adaptation of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement was used to assess the quality of the quantitative studies.56 Examples of methodological limitations include unclear statement of aims, inappropriate recruitment strategy or lack of rigour in data analysis. No studies were excluded based on quality assessment, instead, methodological quality is reflected in the CERQual assessments. Each author independently assessed study quality using the CASP tool and STROBE checklist to qualitative and quantitative studies, respectively (online supplementary files S4 and S5). Using a pre-determined scoring template, each author applied each of the four CERQual criteria to each review finding (online supplementary file S6). After each of the quality assessments and four CERQual elements were evaluated, the CERQual level of confidence for each review finding was assigned as high, moderate or low (RMO, MC, CG-M). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached among authors.

bmjgh-2019-001883supp005.pdf (67.1KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001883supp006.pdf (68.3KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001883supp007.pdf (98.7KB, pdf)

Reporting

This systematic review follows the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement guidelines (online supplementary file S2).57 It also follows the 2009 PRISMA guidelines (online supplementary file S3).58 59

bmjgh-2019-001883supp008.pdf (112.3KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2019-001883supp009.pdf (46.8KB, pdf)

Results

Database searches identified 3529 potentially relevant articles. Thirty-eight published and unpublished reports were retrieved by contacting relevant researchers, for a total of 3567 potentially eligible studies. Of the 191 studies selected for full-text review, 42 studies met inclusion criteria (see figure 1). This systematic review presents primary research findings from 42 studies from 24 LMICs, including 15 countries in Asia and 9 countries in Africa (see table 2). Nineteen studies used qualitative methods, 8 studies used quantitative methods and 16 studies used mixed methods. In 17 studies, the respondents were OSC stakeholders, in 11 studies the respondents were survivors of IPV and/or SV, in 12 studies the respondents were both OSC stakeholders and survivors and in 1 study the respondents were community members.46 OSC stakeholders included government officials in 14 studies, healthcare workers in 15 studies, OSC staff (other than healthcare workers) in 25 studies and police members in 6 studies.

Table 2.

Summary of study characteristics

| Citation number (year) |

Country/ countries |

Study design | Setting characteristics | Sample characteristics, data collection method and recruitment strategy* | Data analysis | Quality assessment |

| 41 (2005) | Bangladesh | Qualitative, descriptive | Two sites; hospital-based; NGO and government run | In depth interviews (n=28) of OSC stakeholders (government, NGO, employees and women survivors) Purposive, snowball sampling |

Thematic analysis | Medium |

| 26 (2006) | Bangladesh | Mixed methods, cross-sectional survey | One site; hospital-based; NGO and government run | Survey (n=310) of women treated at OSC, as identified by medical chart review Purposive sampling |

Descriptive analysis | Low |

| 43 (2013) | Malaysia | Qualitative, descriptive | Seven sites; hospital-based; NGO and government run | In depth interviews (n=54) of OSC healthcare workers (including nurses, medical officers, gynaecologists, medical social workers and hospital managers) Snowball sampling |

Thematic analysis | High |

| 48 (2016) | Nepal | Qualitative, descriptive | One site; hospital-based | FGDs (n=117) of community members, including men (n=41) and women (n=76) Purposive sampling |

Qualitative content analysis | High |

| 12 (2012) | Kenya, Zambia | Mixed methods, comparative case study | Five sites; one NGO-owned stand-alone, one NGO-owned hospital-based, three hospital-owned hospital based |

In-depth interviews (n=25) of female and male survivors of gender-based violence, caregivers of child survivors, hospital managers and key informant interviews; medical chart review, facility inventory review Purposive sampling |

Qualitative: thematic analysis, Quantitative: EpiData and SPSS, accounting approach cost-analysis | Medium-high |

| 11 (2010) | 27 countries in Asia-Pacific; relevant countries include: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives, Nepal, Papau New Guinea, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Timor-Leste | Qualitative, descriptive | Variety of government-led, NGO-led and combined responses, both hospital-based and stand-alone facilities. | Desk review, field visits, phone and email interviews with relevant OSC stakeholders at country and regional offices Purposive sampling |

Content analysis, thematic analysis | Low-medium |

| 46 (2016) | Sylet and Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh | Qualitative, descriptive | Five sites; stand-alone and hospital based; mostly government run with some NGO involvement | Key informant semi-structured interviews (n=124) of United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) staff, government ministries, implementing partners and donors); mixed FGDs (n=12) of government and implementing partner staff, and community beneficiaries; site visits, desk review Purposive sampling |

Content analysis, thematic analysis | Low-medium |

| 44 (2013) | Rwanda | Qualitative, descriptive | one site; hospital-based; government and NGO run |

Semi-structured interviews and FGDs (n=93, breakdown not given) of survivors, OSC staff, and UN and government stakeholders; facility observation Convenience and purposive sampling |

Thematic analysis | High |

| 33 (2013) | Zambia | Qualitative, cross-sectional survey | Eight sites; two stand-alone centres and six hospital-based; all international NGO funded | Survey (n=197) of female and male survivors of IPV or SV who accessed centre Convenience sampling |

Descriptive analysis | Low |

| 30 (2013) | Nepal | Mixed methods | Four sites; hospital-based; government-run | In-depth interviews of female and male survivors of IPV or SV (n=20) and central stakeholders (n=137) including government employees and donors (n=13), health workers (n=58), members of coordination committees (n=42) and other (n=24). Purposive and convenience sampling |

Content and thematic analysis, SWOT analysis | Medium |

| 13 (2016) | South Africa | Qualitative, descriptive | 55 sites (Thuthuzela centres); hospital-based and stand-alone; government and NGO run | Semi-structured interviews and surveys (number not provided) of National Prosecuting Authority staff, NGO staff, OSC managers and national experts in GBV in South Africa; facility observation Non-random sampling not otherwise specified |

Qualitative: thematic analysis | High |

| 51 (2003) | Kenya | Qualitative, descriptive | 10 voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) sites, 11 hospitals, 6 legal and advocacy support programme; one hospital-based, private OSC (gender violence recovery centres) | In-depth and semi-structured interviews of male and female key informants (n=34) and FGDs (n=18) including hospital staff, police officers, government and NGO workers and VCT counsellors; facility observations Stratified and purposive sampling |

Thematic analysis, content analysis | High |

| 45 (2010) | Zambia | Mixed methods | 10 sites; stand-alone and hospital-based, NGO and government- run | Semi-structured interviews (n=240) of key informants including beneficiaries, stakeholders and ministry officials; facility observations Sampling strategy not stated |

Descriptive analysis | Low |

| 37 (2014) | Nepal | Qualitative, descriptive | 16 sites; hospital-based, government-run (Ministry of Health and Population) | Interviews of survivors of IPV and SV, government officials, OSC staff and community members Sampling strategy not stated |

Descriptive analysis | Low |

| 39 (2016) | Pakistan | Mixed methods; cross-sectional, qualitative descriptive | 12 sites; stand-alone, or within government (non-medical) facilities, government-run | Semi-structured telephone interviews (n=136), including female survivors of IPV and SV (n=123), and male and female OSC managers (n=13); field visits and surveys Simple random sampling |

Quantitative: standard statistical techniques, that is, descriptive analysis using SPSS and MS office; qualitative: thematic analysis of the open ended survey and interview questions | Medium-high |

| 38 (2017) | India | Qualitative, descriptive | Four sites; hospital-based and police-station-based, government-run. |

In-depth interviews (n=80) including survivors of sexual assault (n=15), family members of survivors (n=25) and lawyers, civil society activists and advocates (n=15), doctors and forensic experts (n=6), government officials (n=12) and police officers (n=7) Purposive sampling |

Thematic analysis | Medium-high |

| 18 (2002) | Philippines | Mixed methods; retrospective cohort, qualitative descriptive | One site (women and children protection unit); hospital-based, government-run |

Medical chart review of non-pregnant women and children who were survivors of IPV and/or SV (n=1354) Convenience sampling |

Basic descriptive statistical analysis | Medium |

| 19 (2013) | Kenya | Mixed methods; retrospective cohort, qualitative descriptive | One site; Clinic-based, NGO-run (Médecins Sans Frontières) |

Medical chart review of female and male, child and adult survivors of sexual violence (n=866) Purposive sampling |

Basic descriptive statistical analysis using Microsoft Excel and EpiData Analysis 2.1, qualitative descriptive analysis | Medium-high |

| 20 (2015) | Malaysia | Quantitative cross-sectional observational | one site; hospital-based, government-run |

Self-reporting survey of male and female survivors of IPV (n=159) Purposive sampling |

Basic statistical analyses conducted using SPSS V.20. | High |

| 15 (2011) | Malaysia | Qualitative, descriptive | Two sites; Hospital-based, combined NGO and government run |

In-depth interviews (n=20), including policymakers (n=8), NGO representatives (n=7), healthcare workers (n=1) and police and social welfare representatives (n=4) Purposive and snowball sampling |

Content analysis | High |

| 16 (2012) | Malaysia | Qualitative descriptive | Seven sites; hospital-based, combined NGO and government run |

In-depth and semi-structured interviews (n=74) including accidents and emergency doctors (n=23), gynaecologists (n=6), nurses (n=14), medical social workers (n=5), counsellors (n=2), psychiatrists (n=4), policymakers (n=8) and key informants (n=12) Purposive and snowball sampling |

Content and framework analysis | High |

| 49 (2009) | India | Mixed methods; cross-sectional observational, qualitative descriptive | One centre (Centre for Vulnerable Women and Children); stand-alone, combined NGO and government-run | Self-reported reflections and interviews with healthcare workers, female survivors of IPV/SV who utilised the centre (number not provided) Convenience sampling |

Descriptive narrative analysis | Low |

| 10 (2002) | Thailand | Retrospective cohort, quasi-experimental, cross-over | Two centres; hospital-based, government-run | Structured and in-depth interviews (n=249) of female and male hospital staff including physicians, nurses, social workers, psychologists and intake personnel, community women’s leader groups, staff attorneys and police officers Sampling strategy not stated |

Descriptive analysis | Low |

| 21 (2017) | Zimbabwe | Retrospective cohort | One site (Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Clinic); clinic-based, combined NGO (MSF) and government-run |

Medical chart review (n=3617) of female and male survivors of sexual violence, including survivors ages over 16 (n=1071), ages 12–15 (n==615) and ages under 12 (n=93). Census |

Descriptive statistics using Stata V.11. X2 tests, Fisher’s exact tests, logic regression, and model building | High |

| 40 (2009) | Kenya | Qualitative, descriptive | Three sites; hospital-based (emergency department), combined NGO and government-run |

Client exit interviews (n=734) of female and male, child and adult survivors of rape Sampling strategy not stated |

Situational analysis | Low |

| 32 (2009) | South Africa | Before and after intervention; retrospective cohort | One site; hospital-based, government-run |

Semi-structured interviews with female and male survivors of rape (n=109) and service providers (n=16) (doctors, nurses, social workers, a pharmacist and police officers); medical chart review Convenience sampling |

Quantitative descriptive analysis using Stata. Risk ratios estimated using Poisson regression to estimate intervention effect. Qualitative analysis methods not clearly stated |

Moderate |

| 17 (2016) | Democratic Republic of Congo | Qualitative, descriptive | Two sites; Hospital based, privately-run |

Descriptive personal narrative of medical director/obstetrics-gynaecologist and midwife (n=2) | Thematic analysis | Low |

| 22 (2011) | Kenya | Retrospective cohort | One site; hospital-based, government-run |

Medical chart review of female and male survivors of sexual abuse (n=321), including children and adults, (median age 15.9 years; range 8 months to 100 years) Purposive sampling |

Summary descriptive statistics using Stata SE 10.0. Estimates of association calculated using Student’s t-test, X2 tests and Fisher’s exact tests | High |

| 23 (2006) | South Africa | Observational, descriptive | One site (victim support centre); hospital-based, government-run |

Self-reported survey of female and male survivors of rape (n=105) (median age 23.5 years; range 16–68) treated at the centre Purposive sampling |

Descriptive analysis | Low |

| 14 (2010) | Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Senegal, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe | Retrospective cohort, qualitative, descriptive | Seven sites; includes variety of comprehensive care models including Thohoyandou Victim Empowerment Programme, South Africa, and the Kamuzu Central Hospital, Malawi; hospital-based, NGO-run |

Interviews, surveys and medical chart review of survivors of sexual violence, healthcare workers, policymakers, government officials Sampling strategy not stated |

Data analysis methods not clearly stated | Low |

| 24 (2017) | Taiwan | Cross-sectional | Five centres; hospital-based, government-run |

Survey (n=140), using Index of Interdisciplinary Collaboration tool of social workers, doctors, nurses, police officers and prosecutor Purposive sampling |

Statistical analysis via SPSS 18. Multivariate analysis of variance conducted for association analyses, eta-square for power of effect, and multilinear regression for influencers on collaboration | High |

| 25 (2016) | China | Retrospective cohort | Two sites (RainLily); Hospital-based, NGO-run |

Medical chart review (n=154) of female survivors of sexual assault (median age 22 years; range 13–64) Purposive sampling |

Descriptive statistical analysis via PASW Statistics 18, and Mann-Whitney test for highly skewed distributions | Low |

| 31 (2008) | Papua New Guinea | Mixed methods; cross-sectional, qualitative descriptive | ten sites (only Family Support Centres (FSCs) relevant to this review); Hospital-based, government and NGO run | Survey (n=39) of stakeholders (government officials, NGO representatives, and donors; In-depth interviews (n=17) of key informants (donors, service providers, governments officials, local women’s rights activists and faith-based groups) Purposive and snowball sampling |

Descriptive and thematic analysis | Moderate |

| 50 (2016) | Papua New Guinea | Retrospective cohort | One site (FSC); hospital-based, government and NGO (MSF) run | Medical chart review (n=5212) of male and female presentations for SV and/or IPV Purposive sampling |

Statistical analysis via χ2-squared or Fisher’s exact tests, multiple variable adjusted analyses, and modified Poisson regression | Moderate-high |

| 36 (2013) | South Africa | Qualitative, descriptive | Two sites; Stand-alone (near health facility), run by NGO (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime), later transferred to SA government |

Telephone and in-person interviews (n=20) of staff, representatives from government, civil society organisations, UNODC and advisory committees Convenience sampling |

Descriptive and thematic analysis | Moderate |

| 29 (2011) | Malawi | Mixed methods; retrospective cohort, qualitative descriptive | Three sites; hospital-based, combined NGO and government-run | In-depth interviews (n=15) of healthcare workers (including doctors, clinical officers, nurses, midwives, social workers, health surveillance assistants and village health committee members). Key informant interviews (n=12) with policymakers, donors and other stakeholders and FGDs (n=10) with healthcare workers; chart review Purposive stratified sampling |

Qualitative: thematic analysis Quantitative: descriptive statistical analysis and summary statistics via Epi Info, Pearson’s X2 and Fisher’s exact test |

High |

| 47 (2012) | Kenya | Qualitative, descriptive | Four sites (only the Gender-Based Violence Recovery Centre (GBVRC) relevant to this review); hospital-based, government-run |

Semi-structural interviews of female adult survivors of IPV/SV (n=8), and staff members (n=5) (head of department, psychologist, social worker, nurse counsellor and receptionist); client flow observations Purposive sampling |

Thematic analysis | High |

| 27 (2010) | Sierra Leone | Qualitative, descriptive | Three centres (Rainbow Centres); stand-alone, NGO-run |

In-depth interviews and FGDs of (n=101) male and female survivors of sexual assault and (n=22) OSC and NGO staff, including community leaders, judicial investigators, court magistrates and police; facility observations Convenience sampling |

Descriptive analysis | Moderate |

| 35 (2015) | South Africa | Qualitative, descriptive | 29 sites (Thuthuzela centres); variety of hospital-based, stand-alone, police and court-based centres; combined NGO and government run, or only government-run |

In-depth interviews (n=40) of OSC directors and programme managers; participant observation Non-random sampling not otherwise specified |

Descriptive analysis | Moderate |

| 42 (2004) | India | Qualitative, descriptive | One centre (Dilaasa); hospital-based, Combined NGO and government run |

Semi-structured interviews (n=27) of adult female survivors of IPV/SV, including current and former programme participants Purposive sampling |

Content analysis | High |

| 34 (2010) | India | Qualitative, descriptive | Two centres (Dilaasa); hospital- based, combined NGO and government run | Semi-structured interviews with survivors of violence, project personnel, coordinator, mentors and hospital staff (number not specified); facility observation Sampling strategy not stated |

Thematic analysis | Moderate |

| 28 (2018) | Mongolia | Qualitative, descriptive | Four sites; variety of centres–some health facility based, stand-alone, and police-station based, variety of government and NGO-run, funded by UNFPA | In-depth interviews (n=36) and FGDs (n=6) of key informants Sampling strategy not stated |

Thematic analysis | Low-moderate |

*Some details of sample characteristics such as participant sex, age, professional role, specific sampling strategy and data collection and analysis methods were not provided in the primary studies, and thus do not appear in table 2.

FGD, focus group discussion; FSC, family support centre; IPV, intimate partner violence; MOU, memorandum of understanding; MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières; OSC, one stop centre; SOP, standard operating procedures; SPSS, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; SV, sexual violence; VAW, violence against women.

Quantitative synthesis

A total of eight studies with quantitative data had findings relevant to the review.18–25 Meta-analysis was not possible due to wide variations in study designs, measures and outcomes. Instead, descriptions of relevant findings from quantitative studies including data found in results and discussion sections are presented (table 3). Enablers and barriers that emerged from the quantitative studies are incorporated into the thematic synthesis.

Table 3.

Summary of quantitative study findings

| Citation number (year) | Key findings of enablers and barriers | Quality assessment | Themes incorporated into qualitative synthesis (E=enabler, B=barrier) |

| 18 (2002) | There was a delay from time of the abuse to presentation at the OSC, which was attributed to the geographic inaccessibility of the centre, especially for rural populations, as well as lack of community awareness. Higher reporting of sexual abuse cases was attributed to preference among women and children community members to seek care from doctors who specialise in this care and can meet survivor needs. | Medium |

|

| 19 (2013) | There was poor follow-up for medical interventions that required repeat visits. Standardised procedures and protocols assisted in providing quality care to survivors. | Medium-high |

|

| 20 (2015) | There were weaknesses in OSC staff documentation and concerns over survivor confidentiality. OSC staff had unclear roles and responsibilities. Some of the OSC staff were found to have victim-blaming attitudes, and many failed to provide necessary health information to patients. Some staff did not provide rape survivors with sensitive care and failed to spend time to console patients after report of sexual assault. There was a lack of OSC staff training, with more than half of the staff having never attended any training sessions in OSC management even after some had worked for years in the OSC. | High |

|

| 21 (2017) | Follow-up was a common issue, and 42% or 938 survivors had no follow-up | High |

|

| 22 (2011) | 44% of survivors were reported to receive counselling at the centre. There was a lack of available psychosocial support, and only one counsellor was available during standard business hours throughout the duration of this study. There was a lack of support for survivors who presented at night or on weekends. Another barrier was lack of awareness of OSC services and support for women rape survivors in the community. Clear protocols were noted to assist in improved documentation at the centre. | High |

|

| 23 (2006) | There was a lack of survivor-centred care, with privacy concerns. Survivors had to wait in their blood stained, dirty clothes until the healthcare worker could examine them. There was also a lack of provision of health information, such as STI, HIV and pregnancy risk after sexual assault. Long waiting times were also a concern at the hospital. | Low |

|

| 24 (2017) | The perceived degree of interdisciplinary collaboration was lowest among social workers, who felt less trust, respect, informal communication and understanding between collaborators. Healthcare workers perceived the least support from their organisation. Support from higher management and regular interagency meetings were viewed as helpful to improve collaboration. | High |

|

| 25 (2016) | Follow-up attendance after the incident was 57.8%, 63.6%, 59.1% and 46.8% at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months, respectively. Overall, less than half of survivors returned for follow-up visits. | Low |

|

OSC, one stop centre; STI, sexually transmitted infections.

Qualitative synthesis

Nineteen studies used qualitative methods and 16 used mixed methods. Perspectives varied by study, including survivors, staff and other stakeholders such as policymakers and donors (see S4 Table). Tables 4A, B presents the summary of study findings and the CERQual confidence assessments; table 4A presents barriers and table 4B presents enablers.

Table 4A.

Summary of findings: barriers

| Third order themes | Second order themes | First order themes barriers |

Contributing studies | CERQual confidence level | Confidence assessment explanation |

Illustrative examples |

| Leadership and governance | Laws, policies and procedures | Unclear, uncontextualised or unavailable OSC policies and procedures | 10 11 15 29–31 | Moderate | Six studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from 13 countries, including one multi-country study of 11 countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Fairly high coherence. | ‘The 1996 MOH circular did not specify how the centres should be created… In reality, it was very much left at the discretion of each hospital’s director to develop its own procedures.’ (Malaysia, 15) |

| Governing bodies | Ineffective advisory meetings and committees |

Low |

Three studies with moderate to significant methodological limitations. Adequate data but only from two countries. Level of coherence unclear due to limited data, but findings were similar across studies | ‘…some members of the committees … were not regularly participating, or had not been updated by their officials who had participated in meetings. In all four districts a couple of (advisory committee) members were unaware of their [OSC].’ (Nepal, 38) |

||

| Lack of oversight and supervision from governing bodies | 10 11 27 30 36 38–40 | Moderate | 10 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from eight countries. High coherence. | ‘There’s no oversight or monitoring of any of these institutions… There is no monitoring of any kind. Accountability of the government is zero.’ (India, 46) |

||

| Poor transfers of management | 35 36 39 | Low | Three studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from two countries. Unable to assess coherence as only three contributing studies from two countries, but findings were similar among studies. | Poor relationships largely seemed the result of a poorly handled transition from a NGO service to a Thuthuzela Centre (TCC). At two sites respondents reported arriving at work 1 day to be met by National Prosecuting Authority staff, and the announcement ‘This is now our TCC.’ (South Africa, 43) |

||

| Political will | Lack of political will and government investment on issues of IPV/SV | 10–12 15 27 29 31 33 36 38–42 | High | 13 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 12 countries. Moderate to high coherence. | ‘The OSCCs are physically there but then they are not staffed …I felt that they (Ministry of Health) were not willing to put in extra money….I think it is just a political will, it was not their priority.’ (Malaysia, 15) |

|

| Health system resources | Equipment and supplies | Lack of basic medical supplies, facility equipment and survivor comfort items | 11–13 15 26 27 30 35–39 41 42 44 | High | 15 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 14 countries. High coherence. | ‘There were insufficient examination tables, focus lights, and medico-legal investigation materials and no rape or post exposure prophylaxis kits.’ (Nepal, 38) ’Another challenge is we don’t have panties for adult woman so when one is raped she has to leave now the panty for DNA then they go now without panties.’ (South Africa, 13) |

| Information and monitoring | Poor documentation and data management systems | 11 13 19 26–29 31 34 40 41 45 46 | High | 14 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 22 countries. High coherence. | ‘Some staff at specialised and district hospitals were sometimes unsure how to proceed with IPV cases, what injury to document, in what detail, how and what questions to ask, where to refer women.’ (Malaysia, 16) |

|

| Lack of facility-level monitoring mechanisms | 12 13 27–30 34 36 40 45 46 | High | 11 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 22 countries, including multi-country studies from Africa and the Asia-Pacific region. Reasonable level of coherence. | ‘The team has little capacity or tools to systematically collect and aggregate data. No analysis of all the available data to inform the programme and guide implementation is currently being undertaken.’ (Rwanda, 52) |

||

| Operation costs | Operation costs not feasible in low-resource settings | 10 12 15 27–30 33 35 36 38 46 | Moderate | 11 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Relatively thick data from 17 countries. Reasonable level of coherence. | ‘Some OSC services were disrupted by funding constraints; one centre ran without electricity, water, and telephone lines for long stretches of time due to cost.’ (South Africa, 44) |

|

| Lack of designated budgets and budget transparency | 10 30 35–37 45 | Low | Six studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Adequate data from four countries. High level of coherence. | ‘In Malaysia, the OSCs budget was under the emergency department, which resulted in no dedicated budget for OSCs.’ (Malaysia, 15). |

||

| Unsustainable, donor-dependent funding sources | 27 30 35 36 38 42 45 47 48 | Moderate | Nine studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from six countries, and three from South Africa. High level of coherence. | ‘When a contract with one donor ended, it lead five organisations in South Africa, that were reliant on this donor’s funding, to terminate OSC services.’ (South Africa, 43) |

||

| Service delivery | Quality of care | Lack of adequate psychosocial services and staff | 9 13 15 21 25 27 28 30 31 35 38–41 46 47 | High | 16 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 14 countries. High level of coherence. | ‘We are asked to speak with the victims and help them, but we don’t have expert psychologists. I have read some books but … it’s not the same.’ (India, 46) In an evaluation of 12 centres in Pakistan, only one had a psychiatrist. (Pakistan, 47) |

| Failure to provide health information | 13 27 30 34 35 45 | Low | Three studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thin data from three countries. Adequate level of coherence. | ‘The health information given to the participants was also lacking, with the victims not informed about the risk of contracting STIs/HIV or becoming pregnant.’ (South Africa, 31) |

||

| Ineffective clinical care protocols | 15 27 29–31 | Moderate | Five studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from 13 countries, including one multi-country study of 11 countries in the Asia-Pacific region. High coherence. | ‘In the absence of clear guidelines and protocols, clinical services related to GBV remain inconsistent and ad hoc …Without protocols, there is some concern that many healthcare workers will only treat physical injuries and even pass judgement about the survivor’s role in the abuse.’ (Timor-Leste, 11) |

||

| Lack of long-term support and follow-up services | 19 22 26–31 33 35 36 38 40 41 49 | Moderate | Nine studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from 12 countries throughout Africa and Asia. High level of coherence. | ‘We are not able to assure them because there is no follow-up; when they get out of here, everything is like we are finished with them.’ (Zambia, 14) |

||

| Compromised confidentiality and privacy | 19 22 27 59 | High | 12 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from 14 countries. High level of coherence. | ‘One victim’s father fought with the hospital ward sisters for the patient files…we have to make a system such that perpetrators and victims will be anonymous.’ (Nepal, 56) |

||

| Lack of security at OSC | 27 30 36 38 49 | Low | Five studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Adequate data from three countries. High level of coherence. | ‘What our safety is concerned, we are alone here over weekends and at night, and that is quite a risk.’ (South Africa, 13) |

||

| Lack of child and adolescent-friendly services and environment | 15 27 30 33 38 46 | Low | Six studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from five countries. High level of coherence. | ‘Neither NGO-owned OSC had special provisions for… infants and children in their written guidelines or protocols for the clinical management of sexual and gender based violence (SGBV).’ (Kenya, Zambia, 12) |

||

| Accessibility | High out-of-pocket costs to survivors for referral services | 13 25 26 29 30 39 41–43 45 50 | Moderate | 11 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Moderately thick data from 20 countries, including four studies reporting on India. Moderate level of coherence. | ‘Referrals by [OSCs] to other hospitals for cases such as skin grafts, or to an eye hospital or for psychiatric treatment showed no results due to shortages of funds that prevented survivors from going there.’ (Nepal, 38) |

|

| Lack of services on night and weekends | 11 12 21 25 27 31 33 35–38 42 43 46 | High | 14 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 10 countries. High coherence. | ‘Now in my case also, such incidents happened at night, kerosene was poured on me, they tried to kill me, beat me, I couldn’t go anywhere…For the whole night I kept sitting like that.’ (India, 51) |

||

| Long wait times | 13 22 25 26 30 33 35 38 48 | Moderate | Nine studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Adequate data from 10 countries. High coherence. | ‘The OCMC staff nurses were at times unable to provide timely services due to their workloads and consequently some survivors had to wait several hours.’ (Nepal, 38) |

||

| Lack of transportation to OSC | 15 27 30 33 38 46 | Moderate | 12 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from 13 countries, many countries in Africa, including four studies reporting on South Africa. Non-African contexts include studies from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, and Nepal. High level of coherence. | ‘The biggest hurdle we are facing is the lack of transport because…in most cases it is the victim who pays for all transport costs.’ (Zambia, 14) If employed, some survivors could not afford the time off work to make regular trips to the TCC and, if unemployed, did not possess the means for such travel. (South Africa, 43) |

||

| Lack of access to rural populations | 26 27 33 35 42 43 59 | Moderate | Seven studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from 11 countries. High level of coherence. | ‘There was a need to bring more (OSC) services directly to (rural) communities via mobile-support clinics, providing bicycles for counselling staff; or the provision of transport vouchers or refunds for clients.’ (Zambia, 53) |

||

| Lack of community awareness of OSC services | 21 27 29 30 36 37 39 43 45 48 51 59 | High | 13 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 14 countries. High coherence. | ‘Walk-in patients in our one stop centres are very few. Not much awareness. (India, 46) “(The OSC) was largely deserted despite awareness raising efforts.’ (S. Africa, 44) |

||

| Acceptability | Lack of representative staff | 30 37 42 43 47 | Low | Five studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from three countries (Bangladesh, India and Nepal). Adequate coherence. | ‘Women rarely come to police stations to lodge complaints, mainly because the majority of officers are men.’ (Bangladesh, 54) |

|

| Hostile and sceptical community beliefs and attitudes | 15 26 30 35 36 43 | Low | Six studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Adequate data from seven countries. Adequate coherence. | ‘People say, ‘You should not go there. Don’t go to the doctor and don’t go to the police.’ ‘Let’s resolve this matter here at home.’’ (Kenya, Zambia, 12) |

||

| Contextual variations | Hospital-based OSCs expensive and not feasible in rural and/or non-tertiary care settings | 10 11 14 28 | Low | Four studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thin data. Moderate coherence. | ‘It is a reality that this(hospital-based)model can be very costly for hospitals with sparse human resources.’ Kenya and Zambia, 11) |

|

| Hospital-based OSCs decrease priority of other services (eg, legal, justice, social services) | 28 30 | Low | Two studies with moderate to significant methodological limitations. Thin data from two countries. High coherence. | ‘Health facility-based OSCs provide the broadest range of health and psychological services for survivors. However, their linkage to the legal and justice systems is weak.’ (Mongolia, 36) |

||

| Stand-alone OSCs increase risk of stigmatisation | 15 33 47 | Low | Three studies with moderate to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thin data from three countries. Moderate coherence. | ‘It took me a lot of courage before I finally came. When people see you on these benches (in the waiting area), they will say you are one of those women who are normally beaten.’ (Kenya, 55) |

||

| Stand-alone OSCs not equipped to meet medical needs of survivors | 15 27 33 | Low | Three studies with moderate to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thin data from three countries. Moderate coherence. | ‘In the stand-alone model, medical staff are not available 24 hours a day, and survivors need to be driven and escorted to a health facility for services not available at the stand-alone centres (eg, surgery, stitches, x-rays), also during which time evidence may be lost.’ (Zambia, 41) |

||

| NGO-run OSCs less available to allow continuity of care | 26 | Low | One study with significant methodological limitations. Thin data. Unable to assess coherence. | ‘Coordination of voluntary organisation is very poor. NGOs are not available always to ensure the continuity of service.’ (Bangladesh, 34) |

||

| Coordination | Interprofessional collaboration | Weak multi-sectoral collaboration, including lack of equal recognition and respect of implementing partners | 9–11 15 23 25–30 33 35–39 42 43 45–48 50 51 60 | High | 27 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 17 countries. Fairly high coherence. | ‘In some countries, there are a number of different agencies running different OSCCs in different sites… The lack of coordination between these different agencies leads to issues with consistency of care.’ (PNG, 11) |

| Multiple stops/fragmented services | 11 15 30 31 34 39 48 | Moderate | Seven studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from six countries. High coherence. | ‘It is clear that instead of being a “one stop”, the process may at times be lengthy and fragmented.’ (Malaysia, 16) ‘It’s a failed project. The concept was that police investigations, medical, and legal help, all would be provided in one place.’ (India, 46) |

||

| Lack of information sharing between OSC sites | 26 27 29 39 45 | Low | Five studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thin data from 14 countries. Thinness likely due to the difficulty in providing significant detail on inaction (lack of sharing). Reasonable level of coherence. | ‘The new one stop centres devised by the government had failed to consult existing centres or learn from them.’ (India, 46) |

||

| Patient navigation and referrals | Weak referral networks and lack of referral options | 9 11 15 27–30 34 36 37 41 47 50 51 | High | 14 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from 16 countries. High coherence. | ‘Both centres encountered problems of underutilisation due to lack of referrals.’ (South Africa, 44) |

|

| Navigation challenges within facility | 15 30 48 | Low | Three studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Adequate data but only from three countries. Moderate level of coherence. | ‘There was also no information available in citizen’s charters, receptions, outpatient departments, emergency departments and in corridors, thus making it difficult for survivors to locate OCMCs.’ (Nepal, 38) |

||

| Clarity of roles and responsibilities | Unclear responsibilities and lack of ownership of implementing partners | 10 27 29 30 33 35 36 38 39 | Moderate | 11 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from 14 countries. Fairly high coherence. | ‘The assessment team found generally limited horizontal coordination and collaboration between the district-level stakeholders represented on DCCs. This has resulted in inadequate ownership and awareness of OCMC services.’ (Nepal, 38) |

|

| Unclear staff responsibilities and roles | 19 28 30 35 38 39 44 45 | Low | Eight studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from five countries. High coherence. | ‘There seems to be a widespread uncertainty among providers about what their role should include.’ (Malaysia, 51) |

||

| Human workforce and development | Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours | Lack of OSC staff knowledge on IPV/SV | 27 29 30 34 36 44 48 | Moderate | Nine studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from 15 countries. Adequate coherence. | ‘Only a quarter of the providers in Penang mentioned sexual abuse among the types of acts that may characterise domestic violence.’ (Malaysia, 51) |

| Harmful staff attitudes on IPV and SV | 13 19 28 30 34 38 42–44 | High | 11 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 13 countries. High coherence. | ‘Some of them, it is especially those young girls like 14, 15 and 16 years, they also expose themselves to situations that encourage somebody to rape them. Like when we have dancing and the way they behave, sometimes their behaviours itself, the way they walk.’ (Uganda, 14) |

||

| Harmful behaviours of healthcare workers | 19 38 42 43 48 | Low | Five studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from five countries (Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Malaysia, and South Africa). High coherence. | ‘A major problem is that often the victim is treated badly. When she is admitted in the hospital the doctors and nurses do not behave well with the victim and they assume 'she is a bad girl.' They see her as the problem, ‘someone who asked for the problem.’ (Bangladesh, 49) |

||

| Corruption and mistreatment by police | 15 26 34 38 42 43 47 48 | High | 10 studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from 11 countries. High coherence. | Some police officers were found to accept bribes from perpetrators in exchange for dropping survivors’ cases. (Kenya and Zambia, 12) |

||

| Training and development | Inadequate training on trauma informed care and OSC operations | 9 11 15 19 27 29–31 33 34 38 40 41 44–46 | High | 15 studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from 16 countries. High coherence. | ‘More than half of staff at the OSC had never participated in a staff training in OSC management, even after years of working at the OSC.’ (Malaysia, 28) |

|

| Staffing and conditions | Healthcare worker time constraints | 10 11 27 30 34 35 41–44 47 | Moderate | 11 studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from six countries. High coherence. | ‘We don’t have enough time to go in the separate room, to take a long history, so we are not going to ask the reasons why she was battered and go in deep depth on that… it’s just ‘ok, next patient… next patient.’’ (Malaysia, 51) |

|

| Insufficient staff | 11 25–27 29–31 33–38 40 42 44 46 47 | High | 18 studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from 15 countries. High coherence. | ‘Even if they want to come, there are not enough staff, so they cannot come.’ (Malaysia, 16) |

||

| Staff burnout | 16 33 44 45 50 | Low | Five studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from five countries. High coherence. | ‘What I am doing now, I feel it is not enough… I feel very depressed because I can’t do much.’ (Malaysia, 51) |

CERQual, Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research; GBV, gender-based violence; IPV, intimate partner violence; MOH, Ministry of Health; NGO, non-governmental organisation; OSC, one stop centre; OSCC, one stop crisis centre; STI, sexually transmitted infections; SV, sexual violence.

Table 4B.

Summary of findings: enablers

| Third order themes | Second order themes | First order themes enablers |

Contributing studies | CERQual confidence level | Confidence assessment explanation |

Illustrative examples |

| Leadership and governance | Laws, policies and procedures | Supportive laws and policies on VAW | 9 10 25–27 | Moderate | Five studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from five countries. Moderate coherence. | ‘The 1994 domestic violence Law gave IPV what policy theorists in the literature refer to as ‘legitimacy.’ OSCCs acquired national credibility as a feasible policy solution to the VAW problem, resulting in official MOH support on the issue.’ (Malaysia, 15) |

| Standardised policies and procedures | 13 18 21 27 29 31–33 | Moderate | Seven studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 19 countries. High coherence. | ‘The example of Timor-Leste shows how protocol development in line with the local context has been effective.’ (Timor-Leste, 11) |

||

| Governing bodies | Regular interagency meetings to coordinate services and support, address challenges, and delegate tasks | 9 10 23 29 30 33–36 | Moderate | Three studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 14 countries. Fairly high coherence. | Regular interagency meetings with partners from the police, social welfare, legal aid and NGOs, helped improve OSCC services, and, indirectly, forced the government agencies to monitor services.’ (Malaysia, 15) |

|

| Political will | Support from higher leadership | 9–11 23 29 30 33–35 38 43 | Moderate | Seven studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 14 countries, mostly Asia. Fairly high coherence. | ‘The fact that the initial implementation process was government-led added credibility to the request for specific services for abused women and to the entire process, and made it acceptable.’ (Malaysia, 15) |

|

| Service delivery | Quality of care | Available, on-site psychological services and support groups | 10 15 27 30 34 43 45 | Moderate | Seven studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from seven countries. High coherence. | ‘Throughout their interviews, women reported on the benefits of the counselling sessions … many used the terms ‘relieved’ to express how they felt following their meetings with counsellors.’ (India, 50) |

| Minimised return visits and points of care to receive necessary diagnostics and medications | 13 32 | Low | Two studies with moderate to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from seven countries. High coherence. | ‘Patients given a full course of drugs on first visit were much more likely than those given a starter pack with follow-up appointments to have taken PEP for 28 days.’ (South Africa, 40) |

||

| Accessibility | Affordable medical services | 15 30 33 38 | Low | Four studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from four countries. High coherence. | ‘To me, I had no money. Then I thought, hospital=money. I just went home. So later, after a suicide attempt, my friend told me that there are counselling services at Kenyatta (National Hospital) and they are free.’ (Kenya and Zambia, 12) |

|

| Community awareness activities | 13 32 34 43 46 | Low | Five studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 10 countries. High coherence. | ‘A 10-site GBV programme in Zambia utilised community radio programme… 82% of respondents reported having been informed about the GBV programme from the radio phone-in programme.’ (Zambia, 53) |

||

| Contextual variations of OSC models | Hospital-based OSCs better equipped to provide full range of services, including medical services | 11 15 27–29 34 35 43 45 46 60 | Moderate | 10 studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 18 countries. High coherence. | ‘Emergency cases and women in need of urgent care come to the hospital for treatment and so steps can be taken immediately to assist those women.’ (India, 50) |

|

| Hospital-based OSCs more accessible to larger sectors of the population including minority groups | 34 43 45 46 | Low | Four studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thick data from four countries. Moderate coherence. | ‘I particularly liked the fact that it is located within a hospital…since childhood I am seeing all the women coming here.’ ‘It (the location) is good. Women come to the hospital and come to know about this centre, so it is popular.’ (India, 51) |

||

| Hospital-based OSCs better allow multisectoral collaboration | 10 | Low | One study with significant methodological limitations. Thin data. Unable to asses coherence. | ‘The hospital-based OSCCs have particularly good working relationships with the police and public prosecutors and conduct complex case conferences with internal and external partners to ensure effective coordination.’ (Thailand, 10). |

||

| NGO-run OSCs provide better psychosocial support | 15 27 34 38 43 | Low | Five studies with moderate to significant methodological limitations. Fairly thin data from three countries. Fairly high coherence. | ‘The NGO brings skills in research, documentation and training and most importantly, in feminist counselling.’ (India, 50) |

||

| Coordination | Interprofessional collaboration | Strong interprofessional staff relationships | 10 11 30 33 35 36 | Low | Six studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from four countries. High coherence. | ‘The site coordinator had gone out of her way to include all parties in its working and management. It therefore felt more collaborative… and this had helped build trust between parties.’ (South Africa, 43) |

| Human workforce and development | Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours | Sensitive staff attitudes, and behaviours | 11 30 43 44 59 | Low | Five studies with minor to moderate methodological limitations. Thick data from four countries. High coherence. | ‘I had no idea (about Dilaasa at first). But after talking to them (the counsellors) I felt that I have their support. They are ready to help me.’ (India, 50) |

| Referral by sensitive healthcare worker | 43 | Low | One study with minor methodological limitations. Relatively thick data but only from one county, India. Unable to assess coherence as only one contributing study. | ‘The level of sensitivity and care taken (by the physician) to provide this woman with crucial information seems to have been an important factor in facilitating her access to necessary care.’ (India, 50) |

||

| Staffing and conditions | Champion, dedicated OSC staff leaders | 10 13 27 30 36 43 44 | Moderate | Seven studies with minor to significant methodological limitations. Thick data from 13 countries, mostly Asia. High coherence. | ‘The assessment found that, in most cases, OSSCs operated thanks to the hard work of a few dedicated staff members in collaboration with other partners on a very limited budget.’ (India, 50) |

The key barriers and enablers emerging from the review are discussed below by theme.

CERQual, Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research; GBV, gender-based violence; IPV, intimate partner violence; MOH, Ministry of Health; NGO, non-governmental organisation; OSC, one stop centre; OSCC, one stop crisis centre; PEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; VAW, violence against women.

Governance and leadership

Laws, policies and procedures

Supportive laws and policies on violence against women gave OSCs legitimacy and generated high-level commitment from government officials (moderate confidence (MC)).10 11 26–28 Some OSCs that lacked standardised operating procedures (SOPs) struggled to provide consistently high-quality care (MC).10 15 16 28 30 31 The implementation of many SOPs faced significant challenges due to lack of content, contextualisation, availability or visibility within the facility (MC).10–12 15 16 30 31 Conversely, OSCs with SOPs found they enhanced clarity of staff roles, patient flow and referral pathways (MC).10 14 15 19 22 28 31–33

Governing bodies

For some well-established OSCs, regular interagency meetings helped to identify challenges and coordinate responses (MC).10 11 15 24 30 33–36 In two reviews of hospital-based OSCs in Southeast Asia and one stand-alone centre in South Africa, facility-level advisory committees were ineffective, facing challenges such as lack of participation (lower confidence (LC)).30 36 37

Some OSCs found that lack of high-level oversight by OSC management led to uncoordinated and delayed services (MC).11 12 17 28 30 36 38 39 OSCs also faced challenges during transitions of ownership (such as from NGO to local government), and many felt transitions were done hurriedly and without clear instructions, resulting in poor accountability and inter-professional staff relationships (LC).35 36 38

Political will

Many centres across contexts described ‘lack of political will’ as a central cause of facility-level challenges (high confidence (HC)).10–13 15–17 28 31 33 36 38–41 Conversely, executive support, from local managers to national officials, facilitated acceptance of the OSC model (MC).10–12 15 17 24 30 33–35 42

Health system resources

Equipment and supplies

Lack of basic resources was common at OSCs in LMICs, and compromised quality of care (HC).12–14 16 17 27 28 30 35–38 40 41 43 Some sexual assault centres reported insufficient basic comfort items like clean clothes and sanitary pads, as well as other basic supplies (HC).17 28 35

Information and monitoring

Poor documentation and data management were seen across contexts (HC).10 12 14 15 20 27–29 31 34 39 40 44 45 Reasons for this included lack of staff knowledge on how to document violence, outdated information systems, variable record keeping procedures and the ethical and logistical challenges of tracking survivors. A related barrier was lack of evaluation and research; many sites gathered data, but failed to analyse data (HC).10 13–15 28–30 34 36 39 44 45

Operation costs

In 17 different countries, the cost to operate OSCs was a significant challenge, seen at both hospital-based and stand-alone OSCs, as well as government-run and NGO-run OSCs (MC).10 11 13 15–17 28–30 33 35 36 45 Some OSCs were forced to weaken or forgo services due to cost, for example, through decreased operation hours,12 13 17 22 26 28 31 33 35–37 41 42 45 or heavy reliance on volunteers.33 35 36 45 Some of the evaluation teams intended to conduct cost analyses of OSC, but never did due to lack of resources, capacity and data availability, limiting cost data. A challenge seen in some government-run OSCs was lack of budget planning and transparency, due to issues such as stakeholder disputes (LC).11 30 35–37 44 Some non-profit OSCs faced delayed and sporadic donor disbursement of funds which negatively impacted continuity of care and sustainability (MC).17 28 30 35 36 41 44 46 47

Service delivery

Quality of care

In over 14 countries, OSCs of all types were unable to provide adequate psychological support due to lack of trained staff (HC).10 14 16 17 22 26 28–31 35 38–40 45 46 In some of these situations, untrained volunteers sometimes provided psychosocial support.31 33 45 OSCs that provided on-site and trained psychosocial services were better equipped to provide quality care (MC).11 16 28 30 34 42 44

In 14 reports from 10 countries, OSC operation hours were limited on nights and weekends (HC).12 13 17 22 26 28 31 33 35–37 41 42 45 This was perceived to be a major barrier by survivors, OSC staff and OSC stakeholders across settings, as these are times survivors often faced violence. Long waiting times also restricted access to care at OSCs (MC).14 17 23 26 27 30 33 35 47

At some hospital-based OSCs, health workers failed to provide survivors with important health information, such as pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections risk (LC).18 20 23 28 Many OSCs were not equipped to provide follow-up services such as long-term counselling or follow-up medical care, which was perceived to be a barrier by survivors and OSC staff in some settings (MC).14 28 30 34 35 44 At sexual assault centres, minimised points of care was a enabler to adherence and follow-up care, such as providing the full 28-day course of PEP drugs at first visit. (LC).14 32

Survivor-centredness

Data from 14 countries demonstrated that OSCs often violated patient confidentiality and privacy, for example, by lack of private consultation rooms (HC).10 15 17 20 23 27–31 33 35 36 39 40 48 Some OSCs lacked security personnel or systems, and survivors and staff expressed fear for their safety (LC).17 28 30 36 48 Another gap was lack of specific consideration for children and adolescents, for example, by lack of child-friendly environments (LC).16 17 28 30 33 45 A challenge seen at both hospital-based and stand-alone OSCs was multiple survivor interviews where staff asked similar questions, which could result in secondary victimisation (HC).14 17 27–30 33 41 44 47

Accessibility

Free services at the OSC facilitated access to survivors (LC).16 17 30 33 However, 11 reports from OSCs in over 20 countries found that some survivors were forced to pay user fees (MC).10 14 15 26 27 30 38 40–42 44 49 Survivors from rural areas faced geographical barriers to access at OSCs (MC),18 27 28 33 35 41 42 often due to high cost of transportation (MC).14 16 17 27 31 35–37 39 41 44 45

At some hospital-based and stand-alone centres, there were negative perceptions of the OSC by the community (LC).16 27 30 35 36 42 Some communities felt OSCs were temporary or had outsider/donor-driven priorities, leading to challenging power dynamics.30 36

Thirteen evaluations from 14 countries found that communities were unaware of OSC services, (HC)10 15 18 22 28 30 36–38 42–44 47 50 which was linked to low utilisation.10 15 28 36 38 44 47 Awareness raising activities facilitated knowledge of the OSC in some settings,14 32 34 42 45 although in one study in South Africa, there was low awareness despite multiple community raising efforts.36

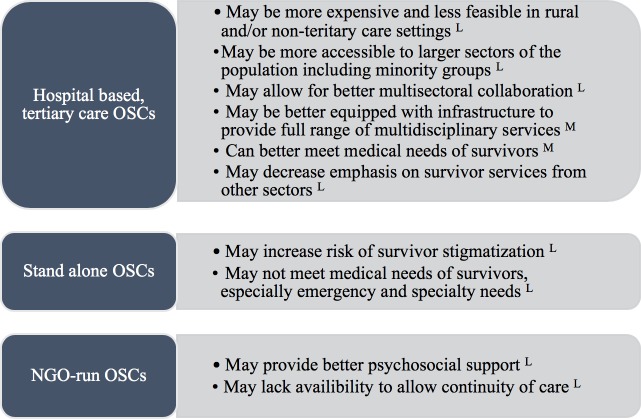

Location of OSC

Hospital based-OSCs were found to be better equipped with the infrastructure to provide comprehensive services (MC).10 12 15 16 28 34 35 42 44 45 51 In some studies, hospital-based OSCs were accessible to a larger population, including minority groups, such as those who identified as indigenous or Muslim (LC).34 42 44 45

Stand-alone were more likely to be known within communities which risked stigmatisation (LC).16 33 47 Some stand-alone centres were unable to manage the immediate medical needs of survivors due inadequate infrastructure, including inability to provide 24/7 services (LC).16 28 33 OSCs managed by NGOs, whether at hospital-based or stand-alone centres, were better equipped to provide survivor-centred psychosocial care (LC).16 17 28 34 42

Coordination and collaboration

Interprofessional collaboration

The most common barrier to OSCs, cited in 27 studies, was poor multisector collaboration (HC).10–12 15–17 24 26–30 33 35–38 41 42 44–47 49–51 Fifteen studies reported weak partnerships with police sectors,10 16 26–28 30 33 37 41 42 46 47 49–51 eight with legal and justice services,10 16 28 30 38 47 49 51 six with shelters27 28 30 42 45 49 and five with NGOs.11 17 26 29 30 Several reports found that OSCs failed to share lessons learnt from implementation with stakeholders (LC).10 15 27 28 38 44 While OSCs were designed to provide all or most services in one location, several evaluations described services as ‘fragmented’ and the facility as ‘not truly one-stop’ (MC).12 16 30 31 34 38 47 Several studies viewed strong interprofessional staff relationships as a enabler (LC).11 12 30 33 35 36

Patient navigation and referrals

Some OSCs lack signage for confidentiality reasons, and some survivors had difficulty locating services within OSCs (LC).16 30 47 Many OSCs noted weak referral networks and lack of referral options (HC).10 12 15 16 28–30 34 36 37 40 46 49 50 Referrals were especially weak in some primary health centres, where specialists and services were most limited.36

Clarity of roles and responsibilities

Implementing partners often disagreed on OSC priorities, responsibilities and budgets (MC).10 11 15 17 28 30 33 35 36 38 At some OSCs, these disputes led to confusion among staff on who and how services should be delivered (LC).17 20 29 30 35 38 43 44

Human workforce and development

Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours

Some health workers at the OSC lacked knowledge on GBV, which was a major barrier, especially in hospital-based OSCs (MC).30 34 36 43 47 Some OSC staff lacked knowledge of services available at their facility.10 15 28 30 47 Many staff held victim-blaming attitudes, such as that survivors solicited attacks by dress or behaviour (HC).14 17 20 29 30 34 41–43 Some OSC staff behaved insensitively to survivors, for example, by scolding rape survivors (LC).17 20 41 42 47 Many studies found both on-site and off-site police officers to have victim-blaming attitudes, and to mistreat survivors (HC).16 17 27 34 41 42 46 47