Abstract

Objective

To describe available evidence from systematic reviews of alternative healthcare delivery arrangements relevant to high-income countries to inform decisions about healthcare system improvement.

Design

Scoping review of systematic reviews.

Data sources

Systematic reviews of interventions indexed in Pretty Darn Quick-Evidence.

Eligibility criteria

All English language systematic reviews evaluating the effects of alternative delivery arrangements relevant to high-income countries, published between 1 January 2012 and 20 September 2017. Eligible reviews had to summarise evidence on at least one of the following outcomes: patient outcomes, quality of care, access and/or use of healthcare services, resource use, impacts on equity and/or social outcomes, healthcare provider outcomes or adverse effects.

Data extraction and synthesis

Journal, publication year, number and design of primary studies, populations/health conditions represented and types of outcomes were extracted.

Results

Of 829 retrieved records, 531 reviews fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Almost all (93%) reviews reported on patient outcomes, while only about one-third included resource use as an outcome of interest. Just over a third (n=189, 36%) of reviews focused on alternative information and communications technology interventions (including 162 reviews on telehealth). About one-quarter (n=122, 23%) of reviews focused on alternative care coordination interventions. 15% (n=80) of reviews examined interventions involving changes to who provides care and how the healthcare workforce is managed. Few reviews investigated the effects of interventions involving changes to how and when care is delivered (n=47, 9%) or interventions addressing a goal-focused question (n=38, 7%).

Conclusion

A substantial body of evidence about the effects of a wide range of delivery arrangements is available to inform health system improvements. The lack of economic evaluations in the majority of systematic reviews of delivery arrangements means that the value of many of these models is unknown. This scoping review identifies evidence gaps that would be usefully addressed by future research.

Keywords: health economics, health policy, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We have followed published methodological guidance for conducting this scoping review.

The search was limited to a 5-year period (2012–2017) to retrieve up-to-date reviews of alternative delivery arrangements relevant to high-income countries.

As this scoping review sought to map the state of the literature in this area, we did not appraise the quality of the included reviews and did not attempt to synthesise the effects of healthcare delivery arrangements in the included systematic reviews.

Systematic reviews that were awaiting classification in ‘Pretty Darn Quick’-Evidence at the moment of search were not captured in the search.

Background

The last century has seen a continuous growth in investment in the health systems of high-income countries.1 This has contributed to significant improvements in population health and a reduction in demand for medical care of communicable diseases, but a proportional increase in demand for the management of chronic and complex conditions.2 3 In addition, advances in medical technology, and more population-based screening and management of disease risk factors have increased the scope of healthcare services.4–8 Taken together, this has fuelled the inflation of healthcare costs.1 The cost of delivering healthcare in most high-income countries is now considered unsustainable and is expected to be unaffordable by the middle of the 21st century without major reforms.1

A challenge for healthcare systems and funders is how to deliver high-value, effective care while slowing (and where possible reversing) the rate of increase in costs. This requires an understanding of the effectiveness and economic impact of current service models and a determination of whether there are alternative models of healthcare delivery that might lead to improved efficiencies without compromising the quality and outcomes of care.

The value of a given model of healthcare service delivery is based on its ratio of benefits and harms relative to its cost.9 10 In an ideal health system, healthcare resources should be allocated across interventions and population groups to generate the highest possible overall level of population health at the lowest cost. In practice, this means reallocating resources away from resource-intensive interventions that have little or no benefit and redistributing to cost-effective and/or resource-wise interventions to enhance the allocative efficiency of health systems. Reconfiguring the way healthcare is delivered may be one method for improving the allocation of finite healthcare resources.

There are a number of different ways that healthcare delivery may be modified, including changing the location that healthcare is delivered (eg, hospital to home), providing care in a group setting rather than to individuals, substituting care provided by one health professional to care provided by an alternative appropriately trained healthcare professional or lay person, or using technology to assist with the provision of care (eg, telehealth). Provision of services in alternative ways such as this may lead to similar, and in some cases better, outcomes for patients. However, they may also modify the costs (or shift them to other stakeholders) or the demand for service due to more liberal access. Therefore, in addition to effectiveness, robust economic evaluations of alternative models of care delivery are required to inform decisions about the allocation of funding based on their relative value. High-cost models that deliver benefits to patients may still be good value, while low-cost models of care that provide little or no benefit may have limited value.9

Numerous systematic reviews summarising the effects of alternative models of care delivery have been published to date. Almost all have focused on changes in the delivery of healthcare for a single condition,11 a change to the scope of practice of a single type of health professional role in a specific setting12 or a single delivery arrangement type, such as chronic disease programmes,13 multidisciplinary care or integrated care interventions.14 A Cochrane overview of alternative delivery arrangements relevant to low-income countries was recently published.15 Given the differences between low-income and high-income countries in terms of service demands and access to specialist care and technologies, the findings of this overview may have less relevance or applicability to service delivery in high-income countries. No similar study of alternative delivery arrangements relevant to high-income countries has been published to date.

The aim of this scoping review was to describe the extent, range and nature of available systematic reviews of alternative delivery arrangements for health systems relevant to high-income countries published in the last 5 years. A time frame of 5 years was chosen to ensure that the review contained evidence and data about effects that are most up-to-date, reliable and potentially ready to implement. A secondary aim was to identify gaps in the availability of up-to-date systematic reviews of alternative delivery arrangements needed to inform health system sustainability initiatives and future research directions.

This review forms part of a 5-year Partnership Centre for Health Systems Sustainability, funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and other partners. The Partnership Centre is a collaborative of investigators, system leaders, expert advisors, system implementation partners and funding partners from around Australia and aims to investigate and create interventions to improve health system performance sustainability (https://www.healthsystemsustainability.com.au/).

Methods

Protocol

The protocol for this scoping review has been published16 (online supplementary file 1). It was informed by the methodological framework that emphasises transparency of the scoping review process to increase the reliability of the findings.17 18 Scoping reviews such as this are particularly useful for systematically mapping research findings across a body of research evidence that is heterogeneous and/or complex in nature. We reported our scoping review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for Scoping Reviews statement.17

bmjopen-2019-036112supp001.pdf (191.4KB, pdf)

Criteria for considering reviews for inclusion

All English language systematic reviews examining the effects of alternative delivery arrangements for health systems relevant to high-income countries published in the last 5 years were included. Alternative delivery arrangements include changes to the method of how and when care is delivered, where care is provided and changes to the healthcare environment, who provides care and how the workforce is managed, coordination of care and management of care processes, and information and communication technology (ICT) systems.18

For inclusion, systematic reviews needed to assess the effects of alternative delivery arrangements of relevance to high-income countries (as classified by the World Bank for the 2017 fiscal year),19 have a methods section with explicit inclusion criteria and report at least one of the following outcomes: patient outcomes (health status and health behaviours), quality of care, access and/or use of healthcare services, resource use, impacts on equity and/or social outcomes, healthcare provider outcomes or adverse effects. As the primary aim of the review was to describe the extent, range and nature of available evidence syntheses published in this area, we included systematic reviews containing trials with or without economic studies, as well as systematic reviews containing trials with or without other study designs (eg, interrupted time series and controlled before–after studies). This is because trials addressing questions about the effects of health system interventions may be difficult to implement and are often not available. Systematic reviews that included interventions in any setting were included and encompassed hospital (inpatient or outpatient care, acute or subacute), primary care, long-term care facilities/residential care and the community.

Search methods for identifying reviews

‘Pretty Darn Quick’ (PDQ)-Evidence was searched to identify systematic reviews of interventions to improve the organisation of healthcare services published between 1 January 2012 and 20 September 2017. PDQ-Evidence is a database of evidence for decisions about health systems derived from the Epistomonikos database of systematic reviews. PDQ-Evidence includes the following databases: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, MEDLINE via PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre Evidence Library and the Campbell Collaboration Online Library. The ‘intervention’ publication filter was used to include only systematic reviews that included studies of interventions and excluded diagnostic (impact and accuracy), prognostic, prediction (diagnostic and prognostic) and qualitative systematic reviews.

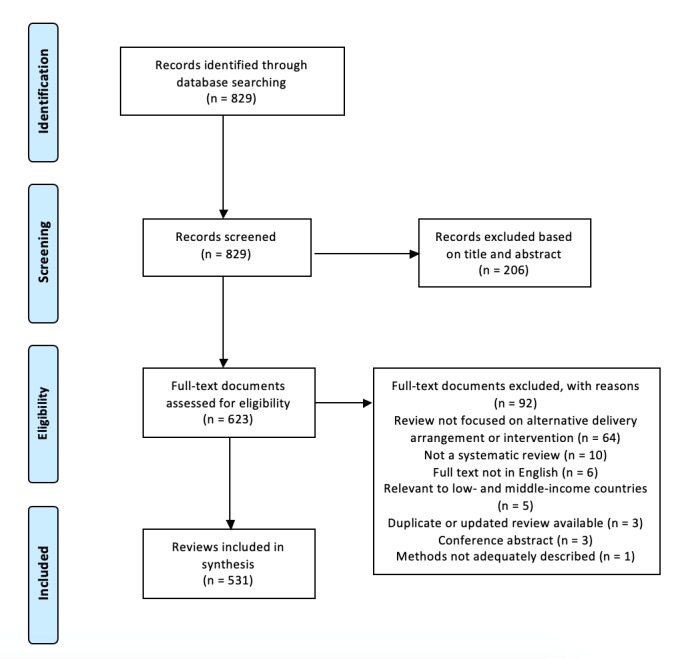

Selection of reviews

Two review authors (RJ and SC) independently screened the titles and abstracts and coded these as ‘retrieve’ (potentially eligible or unclear) or ‘do not retrieve’ (ineligible). At least two of four review authors (RJ, PP, JN and KR) independently screened the full-text reports for inclusion. The reason for exclusion of ineligible systematic reviews was recorded. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or involvement of a third review author (DAOC or RB). A PRISMA flow diagram was developed to summarise the search and selection process (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted on systematic review characteristics (year of publication, authors, number and design of included studies and journal), population, health conditions (where reported), types of outcomes of interest (namely, patient outcomes, quality of care, access and/or use of healthcare services, resource use, impacts on equity, social outcomes, healthcare provider outcomes and adverse effects) and whether reviews included economic analyses. Microsoft Excel software (v14) was used to manage the data. A data extraction form was piloted and refined.20 Review authors involved in data extraction (RJ, PP, JN and KR) independently extracted data from the first 10 included reviews and discussed their findings to ensure consistency. Consistency of extraction was also performed independently by two review authors (RJ and PP) for a third of included reviews to ensure data collection was robust and to determine the level of agreement. As the mean agreement across review authors was 93%, a single-review author independently extracted the data from the remaining included reviews.

Collating and summarising results

Delivery arrangements were categorised using the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy of health system interventions,18 which characterises interventions according to conceptual, functional and/or practical similarities. The delivery arrangement domain of the taxonomy classifies interventions into five categories (and related subcategories) based on changes to the following:

How and when care is delivered.

Where care is provided and changes to the healthcare environment.

Who provides care and how the healthcare workforce is managed.

Coordination of care and management of care processes.

ICT systems.

To this taxonomy we added a category of goal-focused reviews. This was used to categorise systematic reviews that summarised a range of alternative care delivery models across two or more EPOC categories.

As this was a scoping review, rather than an overview of systematic reviews designed to synthesise the results of the included systematic reviews, a critical appraisal of the quality of the included systematic reviews was not conducted.

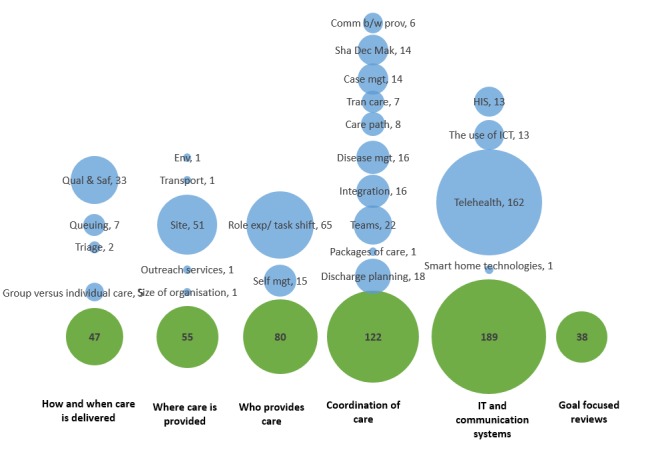

We summarised our findings quantitatively by presenting a numerical count of reviews in each delivery arrangement category, visually using a bubble chart to display the quantity and range of reviews across categories and also using a narrative synthesis. We reported the number of Cochrane reviews in each category, given that Cochrane reviews are considered to have higher methodological quality compared with non-Cochrane reviews.21 22 We also reported the total number of primary studies (of any design) included in the systematic reviews in each category and separately a number of randomised trials in which the model of care was rigorously tested.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Results of search

The search yielded 829 citations. After title and abstract screening, 623 full-text reports were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Ninety-two full-text reports were excluded and 531 systematic reviews were included (figure 1). The citations of included reviews are in online supplementary file 2.

bmjopen-2019-036112supp002.pdf (397.2KB, pdf)

Description of included reviews

Of the 531 systematic reviews, 125 (24%) were Cochrane reviews. A total of 12 230 individual studies were included across all systematic reviews, and these included 6911 randomised controlled trials (RCTs). A total of 106 (20%) reviews focused on common chronic diseases (eg, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, chronic kidney failure, asthma and musculoskeletal conditions), and 53 (10%) reviews focused on patients undergoing lifestyle and prevention interventions. Over 90% of reviews examined the effects of alternative delivery arrangements on patient outcomes (eg, mortality and morbidity). Approximately one-third of reviews reported access and/or use of healthcare services as outcomes. One-third of reviews included economic evaluation studies. Only 12% of reviews included quality of care measures as outcomes, and only 6% and 3% of reviews reported impacts of alternative delivery arrangements on equity and social outcomes, respectively (table 1).

Table 1.

Review characteristics

| Review characteristics (N=531) | Count (%) |

| Year of publication | |

| 2012 | 50 (9) |

| 2013 | 79 (15) |

| 2014 | 67 (12.5) |

| 2015 | 111 (21) |

| 2016 | 216 (41) |

| 2017* | 8 (1.5) |

| Cochrane reviews | 125 (24) |

| Included primary studies (all designs) per review, mean (SD) (range) | 23 (37) (0–463) |

| Reviews including randomised controlled trials | 245 (46) |

| Health conditions/ populations | |

| Common chronic diseases (eg, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, chronic kidney failure, asthma, musculoskeletal conditions) |

106 (20) |

| Cancer | 21 (4) |

| Critically or terminally ill | 16 (3) |

| Patients undergoing lifestyle and prevention interventions | 53 (10) |

| Patients undergoing surgical interventions (including preoperative care and safety checklists) | 18 (3) |

| Mental health conditions | 67 (12) |

| Older adults and aged care | 17 (3) |

| Non-communicable diseases (eg, viral hepatitis, HIV, tuberculosis) | 17 (3) |

| Maternal and child health | 38 (7) |

| Outcomes reported | |

| Patient outcomes (health status and/or health behaviours, eg, mortality, morbidity and cure rates) | 492 (93) |

| Quality of care (eg, adherence to recommended practice) | 62 (12) |

| Access and/or use of healthcare services (eg, waiting time to receive care, readmission rates and length of stay in a facility) | 178 (34) |

| Resource use (including healthcare resources, non-healthcare resources, eg, transportation costs, patient and caregiver time) | 161 (30) |

| Impacts on equity | 30 (6) |

| Social outcomes (eg, poverty and unemployment) | 15 (3) |

| Healthcare provider outcomes (eg, well-being, fatigue, stress and satisfaction) | 68 (13) |

| Adverse effects | 93 (18) |

| Reviews incorporating economic evaluation studies | 177 (33) |

*Incomplete.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the 531 systematic reviews, organised according to the Cochrane EPOC taxonomy. The greatest number of reviews focused on changes to ICT systems used by healthcare organisations to manage the delivery of healthcare (n=189). The majority of these focused on telehealth interventions (n=162). The fewest number of reviews (excluding goal-focused) were concerned with changes to how and when healthcare is delivered (n=47). The reviews relating to each category are described further in more detail.

Figure 2.

Number of included reviews organised according to the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care taxonomy of delivery arrangement interventions. Comm b/w prov, communication between providers; Env, environment; Role exp, role expansion; HIS, Health information systems; ICT, information and communication technology; IT, information technology; Self mgt, self management; Qual & Saf, quality and safety systems; Sha Dec Mak, shared decision making.

How and when care is delivered

Of the 47 systematic reviews included in this category, 14 (30%) were Cochrane reviews. A total of 1085 primary studies were included in systematic reviews for this category, including 394 (36%) RCTs.

Systematic reviews in this category included a number of quality and safety initiatives (eg, use of safety checklists to reduce wrong site surgery), alternative methods for queuing patients (eg, patient-initiated clinics in chronic disease and strategies to reduce waiting times for elective surgery procedures). Many of the reviews in this category were not focused on a specific health condition (n=17, 36%), but they were the greatest number of reviews related to maternal and child health (n=7, 15%) (online supplementary file 3). Few systematic reviews examined group versus individual care (n=5, 11%) (eg, group antenatal care for pregnant women) or triage strategies (n=2, 4%) (eg, improving patient flow the emergency department). There was one Cochrane review focused on walk-in clinics versus physician offices and emergency rooms for urgent care and chronic disease management that did not find any eligible trials.

bmjopen-2019-036112supp003.pdf (124.6KB, pdf)

Where care is provided and changes to the healthcare environment

There were 55 systematic reviews included in this category. Of 1002 primary studies in this category, 323 (32%) were RCTs.

Most reviews investigated changes to the site of healthcare delivery (n=51, 93%) with the majority of these focused on shifting care away from the hospital setting to the home (n=32). The remaining reviews focused on shifting care from the inpatient to the outpatient or day stay setting (eg, outpatient vs inpatient management for acute pulmonary embolism) (n=6); from the hospital to primary or community care organisations (eg, primary care asthma clinics) (n=4); from hospital to a therapeutic community (eg, for mental healthcare) (n=2); provision of care in at site (eg, prehospital vs in-hospital thrombolysis) (n=4); or provision of care in schools (eg, for mental health and health equity) (n=3). A small number of reviews in this category looked at changes to other aspects of the healthcare environment, including the physical or sensory environment (n=1) (rooming-in services for pregnant mothers), outreach services (n=1) (mobile screening clinics for maternal and child health) and transportation services (n=1) (helicopter emergency medical services for adults with major trauma) and centralisation of services (n=1) (for gynaecological cancer).

Ten reviews (18%) in this category focused on maternal and child health; 5 (9%) focused on mental health; and 5 (9%) focused on cardiovascular disease, while the remainder focused on a range of chronic and complex conditions and lifestyle and preventive care (online supplementary file 3). One Cochrane review on home-based phototherapy for the management of non‐haemolytic jaundice in infants found no eligible trials.

Who provides care and how the healthcare workforce is managed

There were 80 systematic reviews included in this category, 18 (23%) were Cochrane reviews. Of 1408 primary studies in this category, 802 (57%) were RCTs.

Most reviews in this category explored substituting medical for appropriately trained nursing care (n=27, 34%) or extending the scope of pharmacists’ practice beyond dispensing services to provision of assessments, diagnosis and education (n=23, 29%). A small number of reviews also looked at self-management versus usual care, with a large focus on management of chronic conditions.

Many of the reviews did not focus on a specific health condition (n=17, 21%) but were focused on changes to workforce roles regardless of condition (online supplementary file 3). For those that did focus on a specific health condition, the largest number was concerned with role expansion to care for patients with different types of chronic disease or multimorbidity (n=8, 10%). One Cochrane review on advanced trauma life support training and role expansion of hospital health professionals and ambulance crews on patient mortality and morbidity did not locate any studies that satisfied the eligibility criteria.

Coordination of care and management of care processes

There were 122 systematic reviews included in this category; 28 (23%) were Cochrane reviews. Of 2554 primary studies in this category, 1619 (63%) were RCTs.

The delivery arrangements in this category included transition care arrangements (eg, hospital to home, from primary to specialist care, or from paediatric to adult services), integrated care models for a range of chronic and complex diseases, early supported discharge to home (eg, for mild to moderate stroke or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary care teams for specific diseases or conditions (eg, geriatric consultation teams in acute hospitals, collaborative care for depression and anxiety). Other delivery arrangements were care pathways (eg, critical care pathways for head and neck cancer surgery), disease management for a range of conditions (eg, prenatal, dementia and mental illness, and intellectual disability) and case management (eg, intensive case management for heart failure, severe mental health, adults with medical illness and complex care needs) (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of included reviews organised according to the Cochrane EPOC taxonomy of delivery arrangement interventions

| Delivery arrangement by EPOC taxonomy category and subcategory | EPOC definition | Reviews (n) (Cochrane reviews, n) | Primary studies (n) (RCTs) | Empty reviews (n) | Types of interventions (see online supplementary file 2 for details) |

| How and when care is delivered (n=47) | |||||

| Queuing strategies | A reduction or increase in time to access a healthcare intervention, for example, managed waiting lists and managing ER wait time | 7 (2) | 112 (22) | 1 |

|

| Group versus individual care | Providing care to groups versus individual patients | 5 (1) | 134 (124) | 0 |

|

| Quality and safety systems | Essential standards for quality of healthcare and reduction of poor outcomes related to unsafe healthcare | 33 (11) | 774 (246) | 0 |

|

| Triage | Management of patients attending a healthcare facility or contacting a healthcare professional by phone, and receiving advice or being referral to an appropriate service | 2 (0) | 65 (2) | 0 |

|

| Where care is provided and changes to the healthcare environment (n=55) | |||||

| Environment | Changes to the physical or sensory healthcare environment, by adding or altering equipment or layout, providing music and art | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

|

| Outreach services | Visits by health workers to different locations, for example, involving specialists, generalists and mobile units | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0 |

|

| Site of service delivery | Changes in where care is provided, for example, home versus healthcare facility, inpatient versus outpatient, specialised versus non-specialised facility, walk-in clinics, medical day hospital and mobile units | 51 (20) | 956 (320) | 1 |

|

| Size of organisations | Increasing or decreasing the size of health service provider units | 1 (1) | 5 (0) | 0 |

|

| Transportation services | Arrangements for transporting patients from one site to another | 1 (1) | 38 (0) | 0 |

|

| Who provides care and how the workforce is managed (n=80) | |||||

| Role expansion or task shifting | Expanding tasks undertaken by a cadre of health workers or shifting tasks from one cadre to another, to include tasks not previously part of their scope of practice | 65 (12) | 1110 (586) | 1 |

|

| Self-management | Shifting or promoting the responsibility for healthcare or disease management to patients or their families | 15 (6) | 298 (216) | 0 |

|

| Coordination of care and management of care processes (n=122) | |||||

| Integrated healthcare systems | Consolidating the provision of different healthcare services to one (or simply fewer) facilities | 16 (3) | 406 (258) | 0 |

|

| Shared decision making | Sharing healthcare decision-making responsibilities among different individuals, potentially including the patient | 14 (5) | 487 (393) | 0 |

|

| Packages of care | Introduction, modification or removal of packages of services designed to be implemented together for a particular diagnosis/disease, for example, tuberculosis management guidelines and newborn care protocols | 1 (1) | 5 (5) | 0 |

|

| Case management | Introduction, modification or removal of strategies to improve the coordination and continuity of delivery of services, that is, improving the management of one ’case’ (patient) | 14 (4) | 375 (260) | 0 |

|

| Disease management | Programmes designed to manage or prevent a chronic condition using a systematic approach to care and potentially employing multiple ways of influencing patients, providers or the process of care | 16 (3) | 298 (169) | 1 |

|

| Care pathways | Aim to link evidence to practice for specific health conditions and local arrangements for delivering care | 8 (2) | 99 (24) | 0 |

|

| Teams | Creating and delivering care through a multidisciplinary team of healthcare workers | 22 (4) | 398 (229) | 1 |

|

| Communication between providers | Systems or strategies for improving the communication between healthcare providers | 6 (2) | 105 (44) | 0 |

|

| Transition of care | Interventions to improve transition from one care provider to another | 7 (0) | 138 (26) | 0 |

|

| Discharge planning | An individualised plan of discharge to facilitate the transfer of a patient from hospital to a postdischarge setting | 18 (4) | 243 (211) | 0 |

|

| ICT systems (n=189) | |||||

| Health information systems | Health record and health management systems to store and manage patient health information, for example, electronic patient records, or systems for recalling patients for follow-up or prevention | 13 (4) | 718 (118) | 0 |

|

| The use of ICT | Technology-based methods to transfer healthcare information and support the delivery of care | 13 (1) | 627 (250) | 0 |

|

| Smart home technologies | Electronic assistive technologies | 1 (0) | 48 (9) | 0 |

|

| Telehealth | Exchange of healthcare information from one site to another via electronic communication | 162 (29) | 3533 (2527) | 2 |

|

| Goal-focused reviews (n=38) | |||||

| Interventions to address social determinants of health | 14 (2) | 319 (123) | 0 |

|

|

| Improving medication adherence | 11 (2) | 654 (551) | 0 |

|

|

| Addressing multimorbidity in primary care | 1 (1) | 18 (18) | 0 |

|

|

| Preventing readmissions | 1 | 42 (42) | 0 |

|

|

| Reducing inappropriate imaging and testing | 3 | 24 (6) | 0 |

|

|

| Meeting family needs of the critically ill | 1 | 14 (1) | 0 |

|

|

| Communicating contraceptive effectiveness | 1 (1) | 7 (7) | 0 |

|

|

| Improving adherence to treatment | 2 | 38 (35) | 0 |

|

|

| Interventions to increase retention in healthcare services | 1 (1) | 11 (9) | 0 |

|

|

| Interventions to increase vaccine uptake | 3 | 128 (77) | 0 |

|

|

| Total | 531 | 12 230 (6911) | 7 | ||

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ED, emergency department; EMR, electronic medical record; EPOC, Effective Practice and Organisation of Care; ER, emergency room; GP, general practitioner; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; ICT, information and communication technology; ICU, intensive care unit; IT, information technology; MS, multiple sclerosis; RCT, randomised controlled trial; STD, sexually transmitted disease; TB, tuberculosis.

Several reviews in this category did not focus on a particular health condition (n=17, 14%); however, a few focused on coordination of care in cancer (n=9, 7%), diabetes (n=8, 7%), maternal and child health (n=8, 7%), cardiovascular disease (n=6, 5%), mental health (n=6, 5%) and for the terminally ill (n=6, 5%) (online supplementary file 3). We identified two reviews that reported they did not locate any studies that met eligibility criteria. One focused on service responses for people with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy, the second focused on specialist teams for neonatal transport to neonatal intensive care units.

ICT systems

There were 189 systematic reviews included in this category; 34 (18%) were Cochrane reviews. Of 4926 primary studies in this category, 2904 (59%) were RCTs.

The largest number of reviews focused on telehealth (n=162, 86%) and included a range of interventions such as telephone counselling, telemonitoring, mobile texting or applications, and internet-based programmes (eg, cognitive–behavioural therapy) (table 2). A smaller number of reviews investigated health information systems (n=13, 7%) (eg, paediatric track and trigger systems for hospitalised children), the use of ICT (n=13, 7%) (eg, ICT interventions for reducing inappropriate imaging and testing) and smart home technology (n=1, 0.5%) (eg, remote monitoring of patients discharged from hospital with heart failure).

The majority of reviews in this category focused on changes to ICT systems for delivering mental healthcare (n=44, 23%), while 39 (21%) focused on delivery of lifestyle changes and preventative strategies for health (n=39, 21%) (online supplementary file 3). There were two empty Cochrane reviews in this category. The first focused on the use of email for communicating results of diagnostic medical investigations to patients; the second focused on telerehabilitation for people with low vision.

Goal-focused reviews

There were 38 systematic reviews included in this category, including 7 (18%) Cochrane reviews. Of 1255 primary studies in this category, 869 (6%) were RCTs. A number of these reviews investigated interventions designed to address health disparities and social determinants of health (14 reviews). These covered a wide range of interventions, some targeting particular populations (eg, for improving access for the homeless to primary care), while others focused on any intervention to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations (eg, community coalition-driven interventions and cultural adaptations of interventions to change behaviour). A further 13 reviews investigated strategies to improve medication or treatment adherence, some targeting particular conditions (eg, pharmacy care and brief messaging to improve medication adherence in type 2 diabetes), others targeting particular medications (eg, lipid-lowering medications).

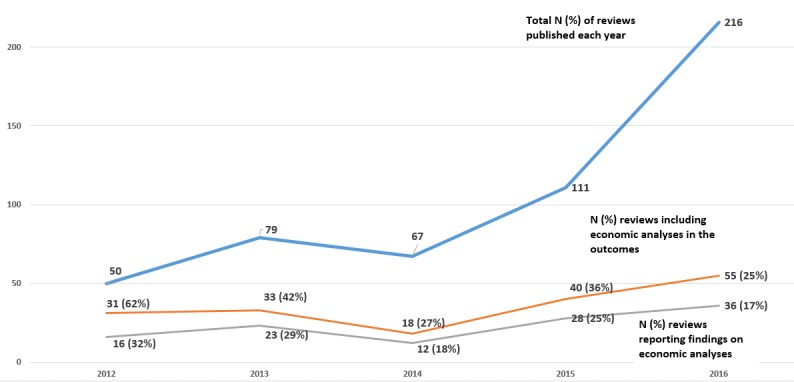

Resource use outcomes and inclusion of economic evaluation studies

Figure 3 provides a summary of included reviews published by year (excluding 2017 as the search of the available literature was not conducted for the full 2017 calendar year), including (1) number of reviews which specified cost as an outcome of interest or aimed to include economic evaluations, and (2) number of reviews that included at least one primary study reporting on costs or economic evaluation. A total of 177 (32%) reviews included costs and/or economic analysis as an outcome of interest, with only 124 reporting at least one primary study including one of these economic outcomes. Resource use (including healthcare resources, eg, length of stay or number of visits to provider; non-healthcare resources, eg, transportation costs, patient and caregiver time) were collected in 161 (30%) of the reviews (table 1).

Figure 3.

Summary of included reviews by year of publication (2012–2016) and incorporating economic analyses.

Discussion

This scoping review describes the extent, range and nature of synthesised evidence of alternative models of healthcare delivery relevant to high-income countries published in the past 5 years. It identified 531 reviews of interventions that involved changes to how and when care is delivered (47 reviews), where care is provided and changes to the healthcare environment (55 reviews), who provides care and how the healthcare workforce is managed (80 reviews), coordination of care and management of care processes (122 reviews), ICT systems (189 reviews) and reviews of interventions addressing a goal-focused question (38 reviews).

We identified variability in the distribution of systematic reviews across the categories of the Cochrane EPOC taxonomy for delivery arrangement interventions; some interventions, such as telehealth and role expansion or substitution, received substantially more attention than others. There were a number of delivery arrangement categories with few published systematic reviews, such as provision of care in a group instead of as an individual, use of triage systems for managing healthcare delivery, changes to the size of healthcare organisations or length of consultations, use of packages of care or smart home technologies. Since the aim of this scoping review was not to examine the extent, range and nature of primary research in this area, it is unclear whether the limited number of reviews on these topics is due to few primary studies or other factors.

Technological advances over the past decade have seen a rapidly changing healthcare landscape that likely explains the large number of reviews we found in the telehealth subcategory. The intense interest in technology belies the barriers associated with their uptake and use, including the upfront and ongoing financial investment in equipment, licensing and software required,23 real or perceived privacy risks, and funding systems that do not always support the delivery of healthcare in this way.24 They are advocated as having potential to enhance care delivery, with the promise of improved capacity for patients to be cared for at home, and improved access for those living rurally or remotely.

Over the past 10 years, there has also been a proliferation of policy decisions both in Australia and elsewhere that have encouraged the development of new or expanded workforce roles to address human resource shortages.25–28 The large number of systematic reviews in this subcategory likely reflects the extensive investment in this area over this time. In addition, there may be other drivers of role expansion for specific health workers; for example, with changes to legislation around supply of pharmaceuticals and a growth in ‘supermarket pharmacies’, there is greater potential for pharmacists to take on additional non-dispensing roles.

While almost all included reviews reported on patient outcomes, only a third of reviews included resource use as an outcome and/or searched for an incorporated economic evaluation studies. Evidence about the economic impact of changes to the way in which healthcare services are organised and delivered is likely to become increasingly important to those making decisions about system redesign and improvement. The lack of economic evaluations in the majority of systematic reviews of delivery arrangements means that the value of many of these models is unknown. Therefore, it is important that the impact of alternative delivery arrangement interventions on these outcomes be considered in future reviews.

There are a number of strengths and limitations to this scoping review. Two authors independently screened and selected reviews, thus minimising the likelihood of omitting eligible reviews. While independent data extraction by two review authors was not feasible due to the large number of included reviews (and is not recommended in methods guidance for scoping reviews20), we did take steps to optimise consistency in data extraction.16 As this scoping review sought to map the state of the literature in this area, we did not appraise the quality of the included reviews and did not attempt to synthesise the results of the included systematic reviews. The search was limited to the last 5 years and only abstracts published on PDQ-Evidence and filtered by the ‘intervention’ category were included. We used the Cochrane EPOC taxonomy for delivery arrangement interventions to map the extent, range and nature of systematic review evidence about alternative models of care delivery but categorisation was not always straightforward. This was because interventions could sometimes be categorised to more than one category (eg, information technology used to improve coordination of care). In these instances, the review team discussed and reached consensus on the categorisation of reviews (see online supplementary file 2). Due to the nature of delays between publication, indexing by databases and capture allocation to the intervention category by PDQ-Evidence, there may be eligible systematic reviews published during our search period but not captured in our search. Since the date of our last search, we have identified 31 systematic reviews indexed in PDQ-Evidence that are potentially eligible for this scoping review. Given this modest volume (5% of current total), addition of this evidence is unlikely to substantially alter the conclusions.

Finally, this review focused on changes in how, when and where healthcare is organised and delivered, and who delivers care and thus excluded consideration of alternatives focused on changes to financial arrangements (eg, changes to how funds are collected, insurance schemes, purchasing of services and use of incentives/disincentives), governance arrangements (changes in rules or processes that determine authority and accountability) and implementation strategies (aimed at bringing about changes in behaviour of healthcare professionals or organisations). Mapping the synthesised evidence focused on these interventions relevant to high-income countries could be described in future scoping reviews.

The findings of this review raise questions that could be investigated in future research. These include exploring to what extent have identified systematic reviews informed policy decisions in Australia and elsewhere? To what extent have decisions to undertake systematic reviews of delivery arrangements been driven by the needs of decision makers versus other motivations? And how can the alignment between review production and the needs of decision-makers be improved? Priority setting approaches that engage both health policy makers and researchers/producers of reviews are likely to increase the availability of reviews relevant to policy and reduce unnecessary duplication of effort. Exploring the need for, and addressing the gaps in, reviews of alternative delivery arrangements highlighted by our review could also be the focus of future work.

The results of the scoping review have informed a Delphi survey to prioritise the most promising alternatives for further investigation. The survey was delivered in two rounds to an Australian panel of policy, clinician, manager, consumer and academic representatives. The next steps include conducting (or updating where relevant) systematic reviews of delivery arrangements ranked as important to the panel and undertaking pilot evaluations (including economic) of high priority, promising alternative delivery arrangements in collaboration with healthcare system partners.

Conclusion

A substantial body of evidence about the effects of a wide range of delivery arrangements is available to inform health system improvements. Most of the available evidence focuses on alternative ICT systems and care coordination models. This scoping review provides a map of the extent, range and nature of available synthesised evidence and identifies gaps where research efforts could be directed, that is, in updating out-of-date reviews or conducting reviews where no reviews currently exist.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The study conception and overall design were conceived by RB and DAOC. RJ, DAOC and PP designed the data extraction tool and RJ, PP, KR and JN assisted in piloting. RJ wrote the first draft of the protocol and DAOC, RB, PP, KR, JN, SC and SS critically reviewed the manuscript, contributed improvements and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Centre for Health System Sustainability (grant ID: 9100002). Along with the NHMRC, the funding partners in this research collaboration are BUPA Health Foundation, NSW Health, Department of Health, Western Australia and The University of Notre Dame Australia. RB is funded by an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (#APP1082138). DAOC is supported by a NHMRC Translating Research into Practice Fellowship (APP1168749).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. All data is presented in the manuscript and supplementary material.

References

- 1.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Fiscal sustainability of health systems: bridging health and finance perspectives. OECD, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker A. Australia's ageing population. 27 Canberra: National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling, University of Canberra, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Healey J. Ageing. 277 Thirroul, NSW: Spinney Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering * commentary: Medicalisation of risk factors. BMJ 2002;324:886–91. 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glasziou P, et al. Too much medicine; too little care. British Medical Journal Publishing Group 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Thijs L, et al. Diagnostic thresholds for ambulatory blood pressure moving lower: a review based on a meta-analysis-clinical implications. J Clin Hypertens 2008;10:377–81. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07681.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills NL, Lee KK, McAllister DA, et al. Implications of lowering threshold of plasma troponin concentration in diagnosis of myocardial infarction: cohort study. BMJ 2012;344: :e1533 10.1136/bmj.e1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forouhi NG, Balkau B, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. The threshold for diagnosing impaired fasting glucose: a position statement by the European diabetes epidemiology group. Diabetologia 2006;49:822–7. 10.1007/s00125-006-0189-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, et al. High-Value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:174–80. 10.7326/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schupbach J, Chandra A. A simple way to measure health care outcomes 2016.

- 11.Langhorne P, Baylan S. Early supported discharge services for people with acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;7:CD000443 10.1002/14651858.CD000443.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martínez-González NA, Djalali S, Tandjung R, et al. Substitution of physicians by nurses in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:214 10.1186/1472-6963-14-214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hisashige A. The effectiveness and efficiency of disease management programs for patients with chronic diseases. Global Journal of Health Science 2013;5:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damery S, Flanagan S, Combes G. Does integrated care reduce hospital activity for patients with chronic diseases? an umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011952 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciapponi A, Lewin S, Herrera CA, et al. Delivery arrangements for health systems in low-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;32 10.1002/14651858.CD011083.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jessup RL, O'Connor DA, Putrik P, et al. Alternative service models for delivery of healthcare services in high-income countries: a scoping review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024385 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) The EpoC taxonomy of health systems interventions, EPOC resources for review authors, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Bank World bank country and lending groups 2017.

- 20.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming PS, Seehra J, Polychronopoulou A, et al. Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews in leading orthodontic journals: a quality paradigm? Eur J Orthod 2013;35): :244–8. 10.1093/ejo/cjs016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Useem J, Brennan A, LaValley M, et al. Systematic differences between Cochrane and Non-Cochrane meta-analyses on the same topic: a matched pair analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144980 10.1371/journal.pone.0144980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blumenthal D. Stimulating the adoption of health information technology. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1477–9. 10.1056/NEJMp0901592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradford N, Caffery L, Smith A. Telehealth services in rural and remote Australia: a systematic review of models of care and factors influencing success and sustainability. Rural Remote Health 2016;16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ford LC. Nurse practitioners: History of a new idea and predictions for the future. Nursing in the 1980s: Crises, opportunities, challenges, 1982: 231–47. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kersten P, McPherson K, Lattimer V, et al. Physiotherapy extended scope of practice – who is doing what and why? Physiotherapy 2007;93:235–42. 10.1016/j.physio.2007.02.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilmore LG, et al. Skills escalator in allied health: a time for reflection and refocus. Journal of Healthcare Leadership 2011;3:53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis N, Robinson L, Brooks PM. Task substitution: where to from here? Med J Aust 2006;185:18–19. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00442.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-036112supp001.pdf (191.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-036112supp002.pdf (397.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-036112supp003.pdf (124.6KB, pdf)