Abstract

Introduction

Gay, bisexual and queer (GBQ) men are at disproportionately higher risk of acquiring HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI). While HIV/STI testing rates among GBQ men are increasing worldwide, they remain suboptimal in a variety of settings.

Methods and analysis

The study is a pragmatic randomised controlled trial designed to evaluate an online video series developed by a community-based organisation in Singapore for GBQ men. A total of 300 HIV-negative GBQ men in Singapore aged 18–29 years old will be recruited for this study. Participants will subsequently be randomised into the intervention arm (n=150) and the control arm (n=150). The intervention arm (n=150) will be assigned the intervention along with sexual health information via a pamphlet, while the control group (n=150) will be assigned only the sexual health information via a pamphlet. Participants should also not have watched the video prior to their participation in this study, which will be ascertained through a questionnaire. Primary outcomes for this evaluation are changes in self-reported intention to test for, actual testing for and regularity of testing for HIV, syphilis, chlamydia and gonorrhoea at the 3 and 6 months after intervention. Secondary outcomes include changes in self-reported risk perception for HIV and other STIs, knowledge of HIV, knowledge of risks associated with acquiring STIs, knowledge of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, consistent condom use for anal sex with casual partners, incidence of STIs, connectedness to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community, self-concealment of sexual orientation, perceived homophobia, internalised homophobia, HIV testing self-efficacy and HIV testing social norms.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board (S-19-059) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov. The results will be published in peer-reviewed academic journals and disseminated to community-based organisations and policymakers.

Trial registration number

Keywords: HIV & AIDS, infectious diseases, epidemiology, public health, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a popular web-based drama series on HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing for young gay, bisexual and queer men in Singapore.

A collaboration with a community-based organisation in Singapore with strong public health translation potential.

Only self-reported data on HIV and other STI diagnoses are collected which cannot be validated through laboratory-confirmed tests.

While steps have been taken to mitigate contamination, the risks nonetheless exist as the intervention material is available to the public.

Sex between men is criminalised in Singapore which may impact participation among subpopulations of the target population.

Introduction

A total of 37.9 million people around the world were estimated to be living with HIV at the end of 2018.1 Gay, bisexual and queer (GBQ) men are at disproportionately higher risk of acquiring HIV, relative to the general population.2 Young GBQ men are a subset of the broader GBQ male community who are especially vulnerable to HIV and other sexually transmitted infection (STI) acquisition. In Singapore, GBQ men between the ages of 15 and 39 years account for 66.3% of all incident HIV cases among GBQ men from the first reported case of HIV in 1986, up to 2018.3

Rates of HIV testing have also remained suboptimal among GBQ men in a variety of settings, including Southeast Asia. A study among young GBQ men in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations countries in 2015 found that 29.9% of participants had never had an HIV test, and these were more likely to be among younger GBQ men.4 Unwillingness to know about their HIV status, the fear of a positive result and low perceived risk of HIV acquisition were factors found to be associated with lower rates of HIV testing among young GBQ men.5 6

As such, there exist numerous types of interventions that aim to increase HIV testing among GBQ men. These interventions range from those that use aspects of peer education, outreach through social media, reminder-based systems, video-based interventions and national social marketing campaigns. These social marketing campaigns were commonly promoted in neighbourhoods where a larger population of GBQ men resided and had substantial number of businesses catering to them.7–11 For reminder-based interventions, participants were recruited from sexual health clinics that they were, at the point of recruitment, attending, either for check-ups or testing.12–14 With regard to the other online interventions such as outreach through social media and peer education, participants were recruited through key websites and mobile phone apps identified to be frequented by GBQ men.15–21

These interventions reported varying degrees of effectiveness in achieving the aims of increasing HIV testing and overall disease awareness. Reminder-based interventions, where participants were reminded every 3–6 months to go for testing through short message reminders sent from designated sexual health clinics, were customised to suit the participants’ level of sexual activity and were effective in promoting the uptake of HIV testing.12–14 Broader scale HIV/STI social marketing campaigns, such as ‘Stop the Sores’ and ‘Stop the Drama Downunder’ from the USA and Australia, respectively, were generally well received and were found to be effective in promoting HIV/STI testing, as well as participants’ knowledge on HIV/STI at the population or community level.8 10 Interventions that collaborated with popular opinion leaders to disseminate HIV prevention messages to GBQ male social networks have also shown success in encouraging desired HIV preventive behaviours.18 19 However, for existing video-based interventions, evidence of their efficacies was not conclusive. In a video-based intervention study conducted in Peru between 2007 and 2008, among participants who self-identified as gay, differences in intention to test for HIV were not statistically significant between the intervention arm and control arm, although participants who identified as non-gay did show increased willingness to do so.21 Several studies also assessed the efficacy of crowdsourced videos on HIV testing, and largely found that they were non-inferior to regular health marketing campaigns,17 or only had a positive effect on HIV testing rates through the use of home-based self-testing kits, but not facility-based HIV/STI testing.22

There are, however, several limitations in the context of reach and feasibility for such interventions. For example, reminder-based and peer education-based interventions require existing health systems that can support such interventions, which may not be feasible in most settings that do not have such services, or where GBQ male-specific clinical services are unavailable due to the criminalisation of sex between men. As such, these interventions may fall short of reaching out to more niche subsets of the GBQ male communities who may be more discreet about their sexual identities and hence may not often visit gay venues or sexual health clinics where these interventions are typically offered.23 Furthermore, while social marketing campaigns have been effective in increasing the uptake of HIV/STI testing, such campaigns may not be feasible in settings such as Asia where negative perceptions of, or attitudes towards GBQ men prevail.4 There have been, however, successes for the impact of social marketing campaigns on HIV/STI testing in the region such as the ‘I Test, Do You?’ campaign in Vietnam, and the ‘TestXXX’ campaigns across the capitals of Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines and Indonesia.24 25

The present study is novel in Asia in evaluating the effectiveness of a web drama series in achieving positive HIV/STI testing-related outcomes for young GBQ men. The videos used in the study form the second season of an educational and web drama mini-series, People Like Us (PLU), developed by gayhealth.sg and Action for AIDS (AFA) in 2018 (https://www.gayhealth.sg/plu/). The first season of the mini-series was screened as a total of 10 film festivals, and won several independent film awards. It had also garnered more than 1.7 million views across various social media platforms since its launch in 2016. In spite of its popularity, little has been done to assess its efficacy in positively impacting HIV/STI testing-related outcomes. If found to be efficacious in improving HIV/STI testing-related outcomes, such web dramas may serve as complementary interventions, alongside clinically based ones, as such web drama series have proven to be easily accessible and shareable, which may facilitate reaching GBQ men who might not have access to healthcare services as a result of key structural barriers, such as stigma.

Methods and analysis

Study aims and design

This is a pragmatic, parallel-group randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a web drama series, developed by a community-based organisation in Singapore, in increasing an individual’s intention to test, self-reported testing behaviours and self-reported regularity of testing behaviours for HIV, syphilis, as well as other common STIs,26 such as gonorrhoea and chlamydia. The trial also aims to evaluate the impact of the web drama series on self-reported risk perception for HIV/STI, knowledge of HIV, risks associated with acquiring STIs and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, consistent condom use for anal sex with casual partners, incidence of STIs, connectedness to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community, self-concealment of sexual orientation, perceived homophobia, internalised homophobia, HIV testing self-efficacy and HIV testing social norms. The pragmatic nature of this trial arises due to the prospect of contamination, as the web drama series had been launched in January 2019. The implications of this are further discussed later in the manuscript.

Study setting

As of end-2018, a total of 8295 Singaporeans had been reported to the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Singapore as having acquired HIV.27 HIV transmission in Singapore is concentrated among key populations, namely among GBQ men and heterosexual men. With regard to HIV testing uptake, about 71.7% of Singapore residents living with HIV are estimated to know their HIV status as of end-2014.28 While GBQ men are more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to be diagnosed through voluntary screening, only 20.0% of incident cases among GBQ men were detected through such means for incident HIV cases reported in the year 2018, compared with 9% among heterosexual individuals. Community-based organisations have actively and regularly promoted HIV and other STI testing in venues frequented by GBQ men and older heterosexual men in Singapore since the beginning of the HIV epidemic,29 there are to our knowledge no available published studies that evaluate the efficacy of these interventions on individual or community-level testing.

HIV testing is widely available at both government-run and private healthcare providers in Singapore, and under the Infectious Disease Act in Singapore, all individuals who test positive for HIV must be notified to the MOH within 72 hours of diagnosis. The anonymous HIV testing scheme was introduced in 1991; under this scheme, no personal information or identifiers are collected during HIV testing at selected clinics to encourage testing among individuals who might otherwise be hesitant of having their identities made known to the authorities. HIV testing is thus only available through facility-based testing, without any options for self-testing or home-based testing as of end-2019.

Singapore society has largely held negative attitudes towards GBQ men and individuals who identify as LGBT.30–32 Legally, sexual relations between consenting male individuals are also criminalised under Section 377A of the Singapore Penal Code, with a penalty of imprisonment for up to 2 years. A recent study found that Singaporeans were also not in favour of its repeal.33 Past studies in Singapore have found that the anticipation of such forms of sexual orientation-based stigma as well as structural forms of stigma and discrimination has a negative impact, while the availability of prompts or peer influence, and accessibility of services were found to have a positive impact on HIV/STI testing among GBQ men.23 34 35 This intervention, with its focus on promoting knowledge of available HIV/STI prevention services in Singapore, modelling HIV/STI prevention-related and other health-seeking behaviours and normalising GBQ male relationships in Singapore, is thus hypothesised to address some of these barriers to the uptake of HIV/STI testing.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for participants in this study include self-reporting at the point of recruitment (1) an HIV-negative status, or being unsure of one’s HIV status; (2) being gay, bisexual or queer with regard to sexual orientation; (3) being of male gender, regardless of sex assigned at birth; (4) being 18–29 years old; (5) being a Singapore citizen or permanent resident; (6) and having never watched an online video drama series by Gayhealth.sg or AFA in the last year.

Exclusion criteria for participants in this study include self-reporting at the point of recruitment (1) having ever watched an online video drama series by Gayhealth.sg or AFA in the last year; (2) an HIV-positive status; (3) not being English literate; and (4) being below 18 or above 29 years old.

Procedure and randomisation

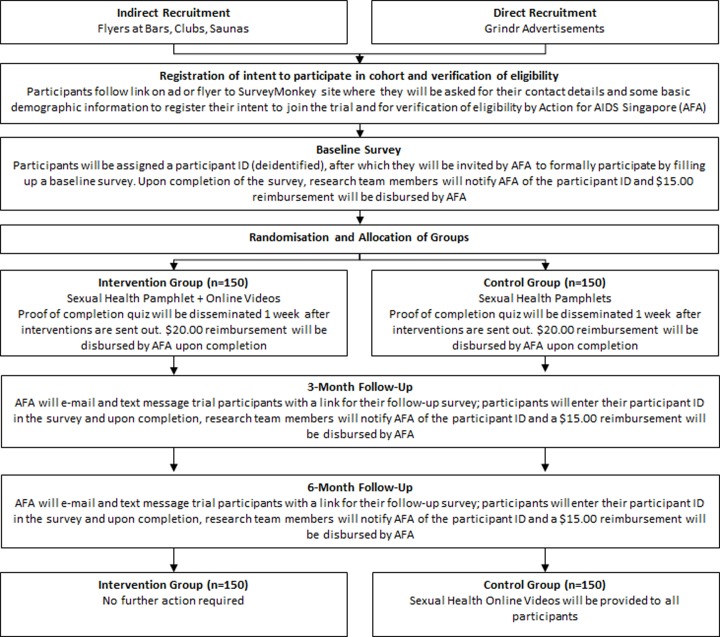

A summary of study procedures may be found in figure 1. Recruitment of participants will take place through the assistance of community-based organisations in Singapore, as well as through advertising channels in popular social and sexual networking apps among young GBQ men. Flyers will be printed and places at the premises run by community-based organisations, while social media campaigns will be run on social media and geosocial networking platforms to recruit participants. To enrol in the study, participants will have to scan a QR code or follow the direct link on the flyer, or click a link on the online advertisement to access a study enrolment questionnaire. Participants will provide consent for participation through an online participant information sheet at this point (see online supplementary material).

Figure 1.

Flowchart for study procedures and randomisation.

bmjopen-2019-033855supp001.pdf (872.7KB, pdf)

Participants will follow the link on the online advertisement or flyer to a survey administration website for a short screening survey where they will be asked for their contact details as well as their self-reported age, sexual orientation, gender, HIV status and residence status to register their intent to join the cohort and for verification of eligibility by the community-based organisational partner, AFA. Participants will also be asked if they had ever watched a web drama series by Gayhealth.sg or AFA launched in the past year without naming the actual series to avoid further contamination. Should the participant be ineligible to participate, they will be redirected to a disqualification page. Throughout the entire survey process, personal identifiers will never be directly linked to survey results, so as to protect participants from potential criminal implications of disclosing their sexual activities with other men and other behaviours such as substance use.

On completion of the enrolment survey and verification of eligibility, a staff member at AFA will contact eligible participants to provide them with their participant ID, and to formally invite them to participate in the study through the completion of the first online baseline survey. This survey will be hosted on a survey administration website and will take about 15–20 min to complete. Participants will be prompted to enter their participant ID at the start of the survey so that on completion, the research team will be able to notify the team at AFA on the completion of the survey, which will allow for direct disbursement of a SGD15.00 (~US$10.84) reimbursement to participants. AFA will not have access to any baseline or follow-up survey responses for the cohort questionnaire, which will only be made available to the study team.

On completion of the baseline survey, participants will then be randomly assigned in blocks of 6 in a 1:1 ratio to the intervention condition or the control comparison condition using a web-based randomisation platform (http://www.sealedenvelope.com) to ensure even allocation. Individuals who are assigned to the intervention condition will be given a link to a series of six online videos from the PLU web drama series, along with a link to an online sexual health pamphlet tailored for GBQ men in Singapore. Individuals who were assigned to the control condition will be scheduled to receive a link to the same online sexual health pamphlet as the standard of care for GBQ men at risk of acquiring HIV/STI in Singapore. To ensure that all participants eventually receive both interventions, after the 6-month follow-up period is over, the control group will receive the link to the online videos as well. All participants will receive their assigned conditions within 1 week after completing the baseline survey, and will be asked to complete a quiz 1 week after assignment to ascertainment if participants had watched the online series and/or read the sexual health pamphlet. Participants will receive a SGD20.00 (~US$14.45) reimbursement following the completion of the quiz.

Participants will not be blinded to the group they have been assigned to, and will be told about their chances of being randomised to either group. However, participants will not have access to the content that would only be delivered at the 6-month mark. The decision to provide both groups similar materials at different times ensures that the trial remains ethical, considering we anticipate improvements in sexual health-seeking behaviour, and ensures that participants remain motivated to participate, knowing that they would receive similar treatments in spite of randomisation. At the 3 and 6-month time frames from the baseline, AFA will contact all eligible participants to continue with their follow-up surveys. Like the baseline survey, the second and third surveys will be hosted on a survey administration website and will take about 15–20 min to complete. Participants will receive SGD15.00 (~US$10.84) reimbursement for the completion of each survey.

The intervention: PLU web drama series

The online intervention comprises a series of six videos, each about 10 min in length, constituting the second season of a popular web drama series entitled PLU. The series follow the love and sex lives of four ethnically diverse GBQ men of varying socioeconomic backgrounds, as they negotiate issues of sexual health, mental health and relationships throughout the six-part mini-series. PLU mini-series incorporates key sexual health messages to (1) increase viewers’ knowledge and perceptions of HIV/STI risk; (2) address homophobia and sexual orientation disclosure; (3) increase safer-sex negotiation self-efficacy; (4) promote positive attitudes towards condom use and other safe-sex behaviours; (5) build skills and self-efficacy for practising safer sex; (6) provide information on HIV/STI testing and its benefits; (7) provide information on resources for HIV/STI testing and other mental health services; and (8) model appropriate behaviours around practising safer sex. Each video in the six-part series ends with an educational video segment featuring the managers and volunteers of AFA and Gayhealth.sg, who provide a brief synopsis of the episode and cover key points relevant to mental and sexual health for GBQ men. A list of episodes may also be found in table 1.

Table 1.

List of episodes and synopses of the People Like Us web drama series season 2

| Episode | Title | Synopsis |

| 1 | Pretty in pink | At Pink Dot, Rai meets Haniff, someone from the same army camp, while Isaac hooks up with someone at his party. Meanwhile, after celebrating their monthsary, Joel introduces his Mom to Ridzwan. |

| 2 | Challenge accepted | As Rai heads out on a first date with Haniff, his Mom discovers a Pink Dot flyer. Joel asks Ridzwan to consider a challenging proposition. Meanwhile, Isaac is unable to concentrate at work and continues to experience pain while peeing. |

| 3 | Signs & omens | Rai’s Mom confronts him about Pink Dot. Isaac is sexually frustrated and receives some disturbing news. Ridzwan seeks out a friend from the past for help while Rai bumps into Haniff, who treats him coldly. |

| 4 | Booty call | Rai’s Mom and sister, Priya, discuss Rai’s sexuality. Haniff surprisingly agrees to meet Rai again but reveals something that will change their relationship forever. Ridzwan accepts Joel’s proposition but will it bring them closer? |

| 5 | Jeremy from work | Joel pays Ridzwan a surprise visit and meets Ridzwan’s Mom. Rai meets Isaac for advice about Haniff. Back home, Rai’s Mom attempts to reconnect with Rai. |

| 6 | A love like ours | Rai and Haniff book out of army camp together; their desires palpable, and Isaac’s party friends desert him. Meanwhile, Joel’s frustration with Ridzwan’s secrecy reaches a breaking point. |

The control condition: sexual health pamphlet

The intervention group will also be provided with an online sexual health pamphlet tailored specifically to the needs of GBQ men in Singapore. This pamphlet was developed by the National Skin Centre and Department of Sexually Transmitted Infections Clinic specifically for information on sexual wellness among GBQ men. It comprises segments on HIV/STI symptoms, aetiology, information on how to seek help for HIV/STI, as well as behavioural and biomedical methods of HIV prevention.

Primary outcome measures

Primary outcomes for this evaluation are changes in self-reported intention to test for, actual testing for and regularity of testing for HIV, syphilis, as well as chlamydia and gonorrhoea at the 3 and 6-month time frames. For example, participants will be asked ‘how likely are you to get tested for HIV in the next three months?’, to which they respond through a 6-point Likert scale from ‘extremely unlikely to get tested’ to ‘extremely likely to get tested’. Self-reported testing is ascertained through the question ‘when did you go for you last (most recent) voluntary HIV test?’ (options to respond include ‘never’, ‘in the last 3 months’, ‘in the last 6 months’, ‘6 to 12 months ago’ and ‘more than 1 year ago’), while self-reported regularity of testing will be measured through the question ‘on average, how regularly do you test for HIV?’ (options to respond include ‘I do not test regularly’, ‘once every few years’, ‘once a year’, ‘once every 6 months’, ‘once every 3 months’ and ‘once a month’).

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes include changes in self-reported risk perception for HIV/STI, knowledge of HIV, knowledge of risks associated with acquiring STIs, knowledge of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, self-reported consistent condom use for anal sex with casual partners, self-reported incidence of STIs and other scales validated among GBQ men in other settings, such as connectedness to the LGBT community,36 self-concealment of sexual orientation,37 perceived homophobia,38 internalised homophobia,39 HIV testing self-efficacy40 and HIV testing social norms.41

Sample size

As the primary outcome of interest includes HIV or other STI testing in the last 3 months, we use data from a recent study conducted in 2018 among 1098 GBQ men recruited through Grindr, the popular geosocial networking app.23 42 The study found that 50.4% of respondents reported having had a recent HIV test in the 6 months prior to the survey. Assuming a 50% increase in recent HIV testing as a result of the intervention, as data from previous studies based on the impact of such a web drama series on recent HIV testing remain limited,43 a sample size of 112 in each arm will yield statistical power higher than 80% to detect a significant change for the intervention, based on calculations generated by a web-based software (http://www.clincalc.com). A target sample size of 150 participants per group is proposed to account for an attrition estimate of 25% for each group across the 6-month follow-up. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis will be employed to assess intervention efficacy on the proposed outcomes. Per-protocol analysis will also be conducted to assess the impact of attrition. Intervention efficacy will be analysed over the entire study period (from baseline to the 6-month assessment).

Statistical analyses

The baseline equivalence of sociodemographic characteristics and sexual behaviour in the intervention and comparison groups will be compared and statistically significant variables between the comparison and intervention groups would be adjusted in the outcome evaluation along with the outcome at baseline. For continuous variables, a generalised linear mixed model will be employed. The mixed models will include intervention status and the time point of assessment as fixed effects, and individuals as a random effect. Between-group effect sizes for the continuous outcome variables will be calculated using post-treatment means and their pooled observed SD. Logistic and Poisson regression models will be employed for binary and count outcome data, respectively. Statistical significance will be set at p<0.05 without any adjustment across the multiple, unique primary outcomes. Statistical analyses will be conducted using the statistical software STATA V.15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Pragmatic nature of trial

The PLU web drama series was launched in the community prior to the start of this study, and thus members of the community might have been exposed to the intervention prior to the study. However, this study was designated to continue in view of its importance in the local context to evaluate the efficacy of such web drama series, and to justify further HIV/STI prevention efforts that use online channels. As such, there is a possibility that control group participants may be exposed to the video series during the 6-month study period. To mitigate this, we will ensure that details of the online video intervention (ie, title of web series, where to access it) will not be included in the participant information sheet—only basic information on the possibility that they may be randomised to an ‘online video intervention’ will be mentioned. Furthermore, to reduce the possibility of contamination occurring in reaction to being asked the screening question, we will avoid using the title of the web series but instead ask the question: ‘Have you ever watched an online video drama series filmed by Gayhealth.sg or Action for AIDS Singapore in the past year?’ as this is Gayhealth.sg/AFA’s only web series launched in the past year. While the generic nature of the question may result in under-reporting of viewing the video series, all participants will eventually be able to view the video series and report if they had viewed any of the episodes prior to, or during the study period. Specifically, participants in the treatment group will be asked if they had previously watched any of the episodes when they submit the intervention completion survey 1 week after the completion of their baseline survey, while the control group will receive a link to all six episodes of the video intervention alongside their final survey at the 6-month mark, and will be asked specifically which episodes that they have watched prior to, or during the intervention period. ITT analyses will be conducted to provide a conservative estimate of the effect of the intervention, regardless of contamination.

A contamination adjusted intention-to-treat (CAITT) analysis may also be performed.44 The authors argue that ‘as-treated’ and ‘per-protocol’ analyses result in non-random omission bias, while ‘intention-to-treat’ analyses underestimate the value of receiving the treatment. In CAITT, the randomised controlled trial is treated as an instrumental variable, with treatment assignment as the ‘instrument’. The effect of treatment assignment on outcome observed (ITT analysis) is adjusted by the percentage of assigned participants who ultimately receive the treatment (contamination adjustment). The authors argue that this provides a good estimate of an individual’s risks and benefits of receiving a treatment, but might overestimate population-level treatment benefits.

At this point, the study team will rely on self-reported outcomes such as testing behaviours and HIV/STI diagnoses as it is presently not possible to link clinic attendance, or laboratory-confirmed diagnostic tests for HIV and other STI to individual participants. These issues have arisen due to ethical concerns around linking participants’ personal information to survey results, which collects information on criminalised behaviour such as sexual intercourse with other men, among participants in the sample. However, the findings of this proposed study will serve as a proof of concept for future studies that may be able to obtain funding and state support for other means of testing, such as the use of self-testing kits for HIV and other STI.

Patient and public involvement

The research protocol and grant application for this evaluation study was developed in collaboration with AFA, and its GBQ health programme, Gayhealth.sg. Both AFA and Gayhealth.sg represent the health interests of the wider GBQ male community and were instrumental in the design and development of the study protocol. The intervention was developed by Gayhealth.sg and AFA Singapore in 2018 following a community needs assessment exercise that identified the pertinent sexual and mental health issues in the local GBQ male community. Results of the study will be disseminated to participants and the wider GBQ male community through both scientific seminars and community-based symposia, as well as through written, open-access reports.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics and mitigating potential risks

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board (Reference number S-19-059). Ethical issues may arise from the recruitment of participants engaging in illegal or criminal activities, such as the self-disclosure of having sex with other men, sex with minors and the use of recreational drugs. To mitigate this risk, the main research team will not have access to any participant’s personal identifiers, or access to any participants directly, which will be carried out by AFA. AFA will only collect participants’ contact information to assist in following up on the surveys, and these will be stored in an encrypted database. On the other hand, staff at AFA will not have access to the survey data containing individual responses. All participants will be assigned a study identification number and these will subsequently be used for communication purposes to ensure that no personal identifiers are reflected or stored beyond the encrypted database.

Dissemination and implications for health promotion and policy

Results of the study will be made available to the public to share the results of the study with the GBQ male community, and to inform policymakers. Specifically, results of the study will be communicated in writing through study reports and peer-reviewed journal articles, and through presentations made in the community, at scientific conferences and at policy meetings. If found to be effective, such web drama series hold great promise to improve HIV/STI testing among GBQ men in Singapore, who are at disproportionate risk of acquiring HIV/STI relative to the general population. The organic growth and reach of the web drama series makes it a cost-effective means of improving such sexual health outcomes among GBQ men, and may serve as a model for other online interventions in Asia, and in contexts where sexual relations between men remain criminalised.

Trial status

Recruitment of participants started in September 2019, and the last participant is expected to reach the primary endpoint (6-month follow-up) in March 2020. Primary data analysis will begin in April 2020. The dissemination phase of the trial results will commence in May 2020.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RKJT and WLK wrote the first draft of the protocol. DL, AvT, AdT, CT and SB developed the materials for the intervention condition and contributed to the details of the intervention in the manuscript. MTWC provided access to the standard of care condition. RKJT, CSW, MLW and MICC obtained funding for the research. All authors conceived the study and revised the manuscript for relevant scientific content in the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Infectious Diseases Programme Research Grant, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore (SSHSPH ID-PRG/SeedFund/2018/03).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval for the protocol was obtained from the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board (Reference number S-19-059).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.UNAIDS Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2019 fact sheet, 2019. Available: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet [Accessed 24 Jul 2019].

- 2.Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. The Lancet 2012;380:367–77. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health Singapore Update on the HIV/AIDS situation in Singapore 2018, 2019. Available: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/infectious-disease-statistics/hiv-stats/update-on-the-hiv-aids-situation-in-singapore-2018-(june-2019) [Accessed 12 Jul 2019].

- 4.Guadamuz TE, Cheung DH, Wei C, et al. Young, online and in the dark: scaling up HIV testing among MSM in ASEAN. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126658. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheim AI, Travers R. Barriers and facilitators to HIV and sexually transmitted infections testing for gay, bisexual, and other transgender men who have sex with men. AIDS Care 2017;29:990–5. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1271937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pharr JR, Lough NL, Ezeanolue EE. Barriers to HIV testing among young men who have sex with men (MSM): experiences from Clark County, Nevada. Glob J Health Sci 2015;8:9–17. 10.5539/gjhs.v8n7p9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephens SC, Bernstein KT, McCright JE, et al. Dogs are talking: San Franciscoʼs social marketing campaign to increase syphilis screening. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:173–6. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bf5a80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plant A, Montoya JA, Rotblatt H, et al. Stop the sores: the making and evaluation of a successful social marketing campaign. Health Promot Pract 2010;11:23–33. 10.1177/1524839907309376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plant A, Javanbakht M, Montoya JA, et al. Check yourself: a social marketing campaign to increase syphilis screening in Los Angeles County. Sex Transm Dis 2014;41:50–7. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedrana A, Hellard M, Guy R, et al. Stop the drama Downunder: a social marketing campaign increases HIV/sexually transmitted infection knowledge and testing in Australian gay men. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:651–8. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318255df06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahrens K, Kent CK, Montoya JA, et al. Healthy penis: San Francisco's social marketing campaign to increase syphilis testing among gay and bisexual men. PLoS Med 2006;3:e474 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou H, Meng X, Grulich A, et al. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the impact of sexual health clinic based automated text message reminders on testing of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men in China: protocol for the T2T study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015787 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou H, Fairley CK, Guy R, et al. Automated, computer generated reminders and increased detection of gonorrhoea, Chlamydia and syphilis in men who have sex with men. PLoS One 2013;8:e61972. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourne C, Knight V, Guy R, et al. Short message service reminder intervention doubles sexually transmitted infection/HIV re-testing rates among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect 2011;87:229–31. 10.1136/sti.2010.048397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou H, Wu Z, Yu J, et al. Internet-Facilitated, voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) clinic-based HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China. PLoS One 2013;8:e51919 10.1371/journal.pone.0051919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Podson D, Chen Z, et al. Using Social Media To Increase HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - Beijing, China, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:478–82. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6821a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang W, Han L, Best J, et al. Crowdsourcing HIV test promotion Videos: a Noninferiority randomized controlled trial in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1436–42. 10.1093/cid/ciw171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau JTF, Tsui HY, Lau MMC. A pilot clustered randomized control trial evaluating the efficacy of a network-based HIV peer-education intervention targeting men who have sex with men in Hong Kong, China. AIDS Care 2013;25:812–9. 10.1080/09540121.2012.749330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko N-Y, Hsieh C-H, Wang M-C, et al. Effects of Internet popular opinion leaders (iPOL) among Internet-Using men who have sex with men. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klausner JD, Levine DK, Kent CK. Internet-Based site-specific interventions for syphilis prevention among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Care 2004;16:964–70. 10.1080/09540120412331292471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blas MM, Alva IE, Carcamo CP, et al. Effect of an online video-based intervention to increase HIV testing in men who have sex with men in Peru. PLoS One 2010;5:e10448 10.1371/journal.pone.0010448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang W, Wei C, Cao B, et al. Crowdsourcing to expand HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: a closed cohort stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002645 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan RKJ, Teo AKJ, Kaur N, et al. Extent and selectivity of sexual orientation disclosure and its association with HIV and other STI testing patterns among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect 2019;95:273–8. 10.1136/sextrans-2018-053866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asia Pacific Coalition on Male Sexual Health APCOM’s TestXXX Initiative Launches in Jakarta as TestJKT, 2017. Available: https://www.apcom.org/apcoms-testxxx-initiative-launches-jakarta-testjkt/ [Accessed 8 Jan 2020].

- 25.PATH Hiv Self-Testing in Vietnam, 2018. Available: https://www.path.org/resources/hiv-self-testing-in-vietnam/ [Accessed 8 Jan 2020].

- 26.Mustanski BS, Newcomb ME, Du Bois SN, et al. HIV in young men who have sex with men: a review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. J Sex Res 2011;48:218–53. 10.1080/00224499.2011.558645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministry of Health Singapore Update on the HIV/AIDS situation in Singapore 2018, 2019. Available: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/infectious-disease-statistics/hiv-stats/update-on-the-hiv-aids-situation-in-singapore-2018-(june-2019) [Accessed 3 Jul 2019].

- 28.Ho ZJM, Huang F, Wong CS, et al. Using a HIV registry to develop accurate estimates for the HIV care cascade – the Singapore experience. J Int AIDS Soc 2019;22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan RKW. Can we end the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in Singapore? Annals Academy of Medicine Singapore 2018;47:499–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathews M. Singapore perspectives 2014: differences. Hackensack, N.J;Singapore: World Scientific Pub. Co, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panchapakesan C, Li L, Ho SS. Examining how communication and demographic factors relate to attitudes toward Legalization of same-sex marriage in Singapore. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 2014;26:355–68. 10.1093/ijpor/edu023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Detenber BH, Cenite M, Ku MKY, et al. Singaporeans' attitudes toward lesbians and gay men and their tolerance of media Portrayals of homosexuality. Int J Public Opin Res 2007;19:367–79. 10.1093/ijpor/edm017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chua LJ, Jie KW, Tan R. Decriminalisation of same-sex relations and social attitudes: an empirical study of Singapore. Hong Kong Law Journal 2017;47:793–824. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan RKJ, Kaur N, Kumar PA, et al. Clinics as spaces of costly disclosure: HIV/STI testing and anticipated stigma among gay, bisexual and queer men. Cult Health Sex 2020;22:1–14. 10.1080/13691058.2019.1596313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan RKJ, Kaur N, Chen MI-C, et al. Developing a typology of HIV/STI testing patterns among gay, bisexual, and Queer men: a framework to guide interventions. Qual Health Res 2020;30:610–21. 10.1177/1049732319870174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frost DM, Meyer IH. Measuring community connectedness among diverse sexual minority populations. J Sex Res 2012;49:36–49. 10.1080/00224499.2011.565427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schrimshaw EW, Siegel K, Downing MJ, et al. Disclosure and concealment of sexual orientation and the mental health of non-gay-identified, behaviorally bisexual men. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81:141–53. 10.1037/a0031272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smolenski DJ, Ross MW, Risser JMH, et al. Sexual compulsivity and high-risk sex among Latino men: the role of internalized homonegativity and gay organizations. AIDS Care 2009;21:42–9. 10.1080/09540120802068803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frost DM, Meyer IH. Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. J Couns Psychol 2009;56:97–109. 10.1037/a0012844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jamil MS, Guy RJ, Bavinton BR, et al. Hiv testing self-efficacy is associated with higher HIV testing frequency and perceived likelihood to self-test among gay and bisexual men. Sex Health 2017;14:170–8. 10.1071/SH16100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Suchindran S, et al. Factors associated with HIV testing among public sector clinic attendees in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Behav 2010;14:913–21. 10.1007/s10461-008-9462-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan RKJ, Teo AKJ, Kaur N, et al. Cost and anonymity as factors for the effective implementation of pre-exposure prophylaxis: an observational study among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Singapore. Sex Health 2018;15:533-541. 10.1071/SH18059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schnall R, Travers J, Rojas M, et al. eHealth interventions for HIV prevention in high-risk men who have sex with men: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e134. 10.2196/jmir.3393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sussman JB, Hayward RA. An IV for the RCT: using instrumental variables to adjust for treatment contamination in randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2010;340:c2073. 10.1136/bmj.c2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033855supp001.pdf (872.7KB, pdf)