Abstract

Background

Marginalised communities such as homeless people, people who use drugs (PWUD), lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people (LGBTI), prisoners, sex workers and undocumented migrants are at high risk of poor health and yet face substantial barriers in accessing health and support services. The Nobody Left Outside (NLO) Service Design Checklist aims to promote a collaborative, evidence-based approach to service design and monitoring based on equity, non-discrimination and community engagement.

Methods

The Checklist was a collaborative project involving nine community advocacy organisations, with a focus on homeless people, PWUD, LGBTI people, prisoners, sex workers, and undocumented migrants. The Checklist was devised via a literature review; two NLO platform meetings; a multistakeholder policy workshop and an associated published concept paper; two conference presentations; and stakeholder consultation via a European Commission-led Thematic Network (including webinar).

Results

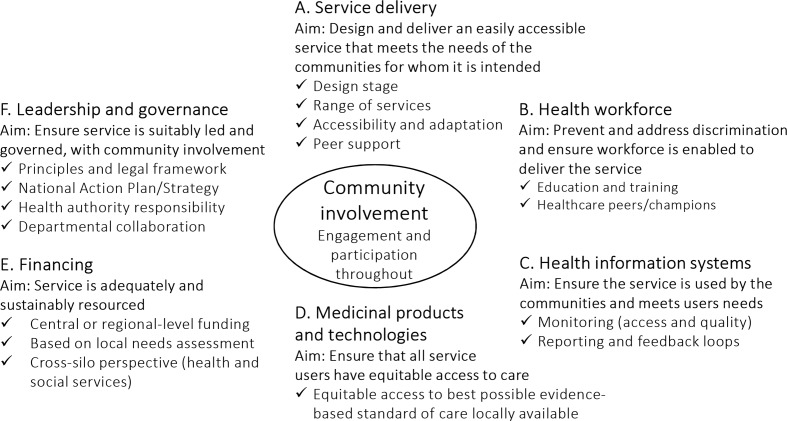

The NLO Checklist has six sections in line with the WHO Health Systems Framework. These are: (1) service delivery, comprising design stage (6 items), services provided (2 items), accessibility and adaptation (16 items), peer support (2 items); (2) health workforce (12 items); (3) health information systems (7 items); (4) medical products and technologies (1 item); (5) financing (3 items); and (6) leadership and governance (7 items). It promotes the implementation of integrated (colocated or linked) healthcare services that are community based and people centred. These should provide a continuum of needs-based health promotion, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment and management, together with housing, legal and social support services, in alignment with the goals of universal health coverage and the WHO frameworks on integrated, people-centred healthcare.

Conclusions

The Checklist is offered as a practical tool to help overcome inequalities in access to health and support services. Policymakers, public health bodies, healthcare authorities, practitioner bodies, peer support workers and non-governmental organisations can use it when developing, updating or monitoring services for target groups. It may also assist civil society in wider advocacy efforts to improve access for underserved communities.

Keywords: health policy, organisation of health services, quality in health care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Nobody Left Outside (NLO) Service Design Checklist is a versatile, easy-to-use, practical tool to help overcome inequalities in access to health and support services in alignment with principles of person centricity and universal health coverage.

The Checklist is broad in scope and hence applicable to services targeting multiple marginalised groups that often intersect and face common access barriers.

The Checklist has been codeveloped by community advocacy organisations and may help other advocacy organisations to collaboratively engage in service design and action plan formulation with key health agencies and health service providers.

The Checklist is not universally applicable nor exhaustive.

The Checklist has yet to be refined based on case studies of implementation.

Background

According to the principle of universal health coverage (UHC), all people should have access, without discrimination and exposure to financial hardship, to nationally determined, basic health services.1 2 UHC encompasses health service delivery, human resources, health facilities, health technologies, information systems and communications networks, quality assurance mechanisms, governance and legislation and financing.

Even in the high-income countries of the European Union and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a large number of people are underserved by health systems. This is particularly true for socially excluded people such as homeless people, people who use drugs (PWUD), lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people, prisoners, sex workers and undocumented migrants. These communities are at a significantly higher risk of poor health than the general population, owing to high levels of stress and precarious living conditions that can increase their vulnerability to certain infectious diseases, such as HIV and viral hepatitis, mental health conditions, maternal health problems, poor dental health and violence-related trauma.3–8 In high-income countries, most chronic non-communicable diseases are substantially more common and have worse outcomes in marginalised groups, as compared with the general population.3–5

Despite their risks of poor health, these marginalised communities face substantial challenges in accessing health and support services owing to a complex interplay of educational, cultural, organisational, administrative, economic and legal barriers, together with widespread stigma and institutional discrimination.6–11 Their general exclusion from healthcare planning and monitoring processes results in a misalignment between service design and the needs of target groups and contributes to poor health outcomes. An emergent approach termed ‘inclusion health’ aims to address such extreme health and social inequities.12

The Nobody Left Outside (NLO) platform is a European coalition of organisations representing marginalised, underserved communities. To address the complexity of the challenges they face in accessing services, NLO partners have worked to create a framework for the delivery of care in a way that addresses many of the overlapping needs of these communities. Designated as a 2019 Thematic Network under the Health Policy Platform of the European Commission (https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/hpf/), the NLO coalition published a Joint Statement on priority measures to improve access to health and support services for marginalised populations in October 2019.13 People from the target community should be involved in service design, or redesign, to help ensure that it addresses relevant barriers to access. Accordingly, the NLO Service Design Checklist aims to promote a collaborative and evidence-based approach to service design and monitoring. It is intended to help service providers, monitoring and evaluation experts, policymakers and target communities (eg, civil society organisations and patient groups) to design and deliver health and support services that are accessible to underserved, marginalised people. Here, we describe the NLO Service Design Checklist, a novel tool to help key stakeholders tailor health services to marginalised communities.

Methods

The Checklist was a collaborative project involving representatives of the following advocacy organisations working together as the NLO initiative: Africa Advocacy Foundation (AAF), Correlation European Harm Reduction Network, European AIDS Treatment Group (EATG), European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (FEANTSA), European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), Hepatitis C Trust, International Committee on the Rights of Sex Workers in Europe, International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association Europe (ILGA Europe) and the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants, together with the Barcelona Institute for Global Health. Representatives of each organisation were involved during the conception, development, revision and final approval of the Checklist.

The Checklist was developed with particular reference to the following communities: homeless people, PWUD, LGBTI people, prisoners, sex workers and undocumented migrants, although its utility is not intended to be limited to these groups.

The Checklist was devised via the following steps: a literature search (via PubMed and other online sources) regarding disease burden, barriers to accessing care, guidelines for interventions and system design and delivery; a published concept paper14; two NLO platform meetings (to define the Checklist concept, structure and items) followed by multiple revision cycles and an open multistakeholder policy workshop at the European Health Forum Gastein 2017. The draft Checklist was then subject to further open stakeholder consultation via the 2019 NLO European Commission-led Thematic Network (including a webinar15 and call for written feedback) and presentations at two conferences: an oral presentation at the International Conference on Integrated Care 201916 and an e-poster at Lisbon Addictions 2019.17

It is structured into six sections according to the WHO Health Systems Framework: service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, medical products and technologies, financing and leadership and governance (figure 1).18 It also aligns broadly with the principles of the European Framework for Action on Integrated Health Services Delivery19 and other international recommendations.9 12 20–24

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of Nobody Left Outside (NLO) service design checklist, based on the WHO Health Systems Framework.18

The Checklist serves as a guide and is not necessarily exhaustive. It will be freely available online (at www.nobodyleftoutside.eu) as an open-access resource, together with a document designed to assist its implementation by providing further explanation, guidance, evidence and links to further resources. Users will be invited to report their experience and to provide feedback to help inform future editions.

Results

Service delivery

Design stage

Marginalised groups are often described as ‘hard to reach’, whereas from their perspective, it is frequently the services that are hard to reach. Section A (table 1) aims to aid the design and delivery of easily accessible services that meet the needs of target communities. Specifically, it promotes the implementation of integrated (ie, co-located or linked) healthcare services that are people centred and which provide a continuum of relevant services, according to users’ needs, as called for by WHO2 and the OECD.25 It aligns with the principles of disease-specific and population-specific, yet broadly applicable, guidance on service design and delivery by WHO and the United Nations (UN).9 19 26

Table 1.

Nobody Left Outside service design checklist: section A—service delivery

| A. Service delivery Aim: design and deliver an easily accessible service that meets the needs of the communities for whom it is intended. Relevance: providers ✓✓ policymakers ✓ |

Yes | No | Not relevant/comments |

| Design stage | |||

| A1. Were people from the target community involved in the design of the service? | |||

| Has the design of the service taken into account the: | |||

| A2. Health and social care needs of the community? | |||

| A3. Existing barriers to service access for the community, identified by the community and/or service users? | |||

| A4. Existing barriers identified by healthcare staff in delivering services to the community? |

|||

| A5. Existing resources and skills within the community? | |||

| A6. Relevant clinical practice guidelines and/or best practices? | |||

| Services provided | |||

| A7. Does the service provide integrated access (colocated or linked) to the range of health services (including testing, treatment, prevention and supportive care), social services and legal services needed by the community? | |||

| A8. Are the physical and psychological needs of each service user systematically assessed on an individualised basis and in an appropriate manner? | |||

| Accessibility and adaptation | |||

| Is the service made easy to access and use by the community by: | |||

| A9. Providing community-based and/or mobile clinics? | |||

| A10. Having convenient opening hours? | |||

| A11. Providing child-friendly waiting areas? | |||

| A12. Providing physical accessibility for people with reduced mobility? | |||

| A13. Providing accessible sex-segregated or gender-segregated spaces and services that are safe and accessible for trans, non-binary and intersex persons? | |||

| A14. Being provided on an anonymous or confidential basis? | |||

| A15. Not requiring users to provide formal identification to access the service? | |||

| A16. Being free-of-charge to users? | |||

| A17. Providing user-friendly information in plain language on the available health, social and legal services and users’ rights to access these, translated into relevant languages and sufficient for them to make informed choices? |

|||

| A18. Being suitably tailored to be sensitive to users’ sexuality, ethnicity, migration status, culture, faith, gender, housing status and lifestyle? | |||

| A19. Allowing users the option to choose which gender of staff member they see? | |||

| A20. Providing trained interpreters for relevant languages during consultations? | |||

| A21. Offering users assistance with completing forms or other documents? | |||

| A22. Being promoted and signposted effectively within the community? | |||

| A23. Providing incentives (eg, financial) for users to use the service? | |||

| A24. Using digital tools with evidence of benefit to help link people to care? | |||

| Peer support | |||

| A25. Does the service use peer care and support by community members? | |||

| A26. Are peer support workers adequately compensated for their services? |

Among key considerations, service design should be based on an up-to-date assessment of:

The specific needs and size of target communities (checklist item A2).

Existing access barriers, identified in consultation with the target community (A3) and healthcare staff (A4).

Latest evidence-based clinical practice guidelines or best practices (A5) and existing resources and skills within target communities (A6).

Services provided

Services targeting marginalised groups should provide convenient and efficient access to the range of health and social services needed by users (box 1; A7). Integrated (ie, colocated or linked) services offer opportunities for multifaceted screening, care and support for health and social issues beyond the initial reason for contact, subject to individualised assessment (A8).

Box 1. Range of services that may be required by people from marginalised, underserved communities targeted by the Nobody Left Outside Service Design Checklist.

Harm reduction

Opioid substitution therapy.

Needle and syringe exchange.

Alcohol and substance abuse interventions.

Infectious diseases testing (with appropriate counselling), linked to treatment services – including for HIV, hepatitis B and C virus and tuberculosis.

Vaccination and other prevention approaches.

Condom distribution.

Wound care.

Other health services

Sexual and reproductive health services (including screening, diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases and cervical cancer screening).

Dental care.

Maternity care services (including conception and pregnancy care).

Mental health services.

Health promotion education.

Social and support services

Housing or shelter support.

Social and welfare services.

Legal support services.

Harm reduction services (box 1) are a priority among many marginalised communities and are essential to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and WHO targets relevant to HIV and viral hepatitis22 23 and yet are limited in most countries and settings, for example, prisons.8 Other health services of particular relevance include vaccination, sexual and reproductive health, mental health, dental care and maternal health. Many of these services correspond to indicators proposed by WHO to measure UHC2 and among vulnerable communities are often subject to variations in access within Europe.

Access should also be provided to housing, which has an extremely important, yet widely neglected, impact on healthcare access and outcomes.5 12 27 Access to legal services can often be critical also, for example, to undocumented migrants to help them understand their entitlement to care, to link them to the healthcare system where possible and to facilitate regularisation of their status.28

Accessibility and adaptation

Services should be designed to be easy to access and use by target communities. Services targeting marginalised groups should be delivered primarily from community-based centres located conveniently for users, supported by mobile outreach units where appropriate, rather than hospital-based clinics (item A9).9 12 20 26 Colocation of multiple services can further facilitate wider engagement and uptake. Target communities can play a key role in designing, delivering and assessing these services.

For example, PWUD—a population that is challenging to engage and retain in health services—often use and trust harm reduction services, particularly when staffed by peers (people with lived experience of challenges similar to those faced by the service user).29 Moreover, such services offer opportunities to provide wider healthcare, support and health education.20 26 Engagement in care for hepatitis C virus or HIV infection may in turn contribute to reducing risk behaviours and supporting harm reduction. The Checkpoint centres across Europe30 and the 56 Dean Street clinic in London31 offer examples of good practice in community-based HIV services targeting key populations. Service models specifically targeting homeless people include integrated multiprofessional services within shelters or community-based outpatient clinics and mobile primary care outreach teams.32

Prisoners are another example of a group facing specific challenges in accessing healthcare. In particular, access to secondary care may be limited by the prioritisation of security measures over healthcare services, while primary care services in prisons are often not provided to the same quality as in the community. Prisons therefore represent an important opportunity for multifaceted public health interventions, for example, voluntary testing and care for sexually transmitted infections and blood-borne viruses20 22 23 and inter alia care for dental and mental health issues.

Checklist items A10–24 (table 1) offer various additional practical considerations to improve accessibility to target groups, including free-of-charge access, confidentiality or anonymity, convenient opening hours and measures to support informed decision making by users. Methods to further promote and monitor service engagement and adherence include sign-posting within target communities (item A22) and peer support work by community members (A25–26). Digital health tools, especially mobile phone apps, also show promise for this purpose (A24).33–35 For example, the Refaid app (https://refaid.com) shows migrants and refugees the location of nearby services. However, the evidence base supporting these interventions is limited at present, and care must be taken to ensure that their use does not contribute to widening health inequalities.

Health workforce

Health and social care providers often lack up-to-date, evidence-based education and training to deal with the complex challenges faced by marginalised communities and may lack evidence-based guidance and support structures. Discrimination within healthcare settings towards marginalised groups can also be an important barrier to access and can compromise care.36 All staff members who serve such communities therefore require specific training on the health, social, economic and other relevant aspects necessary to enable them to effectively engage with and support service users (table 2; items B1–B12). Better training of staff in non-health provider settings (such as homeless shelters) in such matters could also lead to earlier and better referrals to the healthcare system.

Table 2.

Nobody Left Outside Service Design Checklist: sections B (health workforce), C (health information systems) and D (medical products and technologies)

| B. Health workforce Aim: prevent and address discrimination and ensure workforce is enabled to deliver the service. Relevance: providers ✓✓ policymakers ✓ |

Yes | No | Not relevant/comments |

| Do all staff members receive education and training on: | |||

| B1. Health and social care needs and challenges among underserved communities? | |||

| B2. Users’ rights to health and social services, and principles of non-discriminatory equal access? |

|||

| B3. Sensitivity regarding relevant cultural, faith, gender and lifestyle matters among user communities? |

|||

| B4. Communication skills (including appropriate terminology)? | |||

| B5. Stress management? | |||

| B6. Conflict management? | |||

| B7. Do healthcare staff receive suitable training to deliver the necessary services according to current evidence-based guidelines and best practices? | |||

| B8. Is the training provided to healthcare staff accredited for continuing medical education? | |||

| B9. Are peer support workers given suitable training to fulfil their roles? | |||

| B10: Are healthcare staff and peer support workers given peer-to-peer support, supervision or psychological aid, if necessary? | |||

| Do workforce training programmes include contributions from: | |||

| B11. People from the target community? | |||

| B12. Professional peers (‘champions’)? |

| C. Health information systems Aim: check that the service is used by the community and meets users’ needs. Relevance: providers ✓✓ policymakers ✓ |

Yes | No | Not relevant/comments |

| C1. Are people from the target community involved in how the service is assessed? | |||

| Are suitable systems in place to monitor the: | |||

| C2. Usage of the service by the communities? | |||

| C3. Quality and impact of the service provided? | |||

| C4. Is there a formal process to capture users’ feedback on the service, including complaints? | |||

| C5. Are feedback loops in place to ensure that monitoring and user feedback help to improve the service? | |||

| C6. Are data gathered (with informed consent where appropriate and in a data protection-compliant manner) for research and advocacy purposes? | |||

| C7. Does the service apply quality standards? |

| D. Medical products and technologies Aim: ensure that all service users have equitable access to care. Relevance: providers✓✓ policymakers ✓✓ |

Yes | No | Not relevant/comments |

| D1. Do care protocols, guidelines and policies provide all service users with equitable and barrier-free access to medical products and technologies according to the best possible, evidence-based standard of care that is locally available? |

Health information systems

Accurate, relevant health information is required to support evidence-based policy and service design and to ensure that services reach and benefit target communities. Numerous evidence gaps exist with respect to the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of services for marginalised groups. Collecting data regarding the health of marginalised people can be difficult and national data collection systems are limited and heterogeneous between countries,6 7 hampering international comparisons and benchmarking as well as national policymaking.

The Checklist items in this section (table 2) aim to ensure that suitable systems are in place to capture service users’ feedback and measure service quality and that people from target communities (including but not limited to community advocacy organisations) are involved in this process.

Medical products and technologies

In 2017, 12 agencies of the UN called on member states to put in place guarantees against discrimination, as manifest when some individuals or groups are denied access to services that are otherwise available to others—a key barrier to the achievement of the SDGs.36 For example, among PWUD and migrants in Europe, antiretroviral therapy for HIV is more likely to be delayed and to show worse outcomes as compared with people living with HIV not part of these groups.37 38 Other examples include the limited, uneven implementation of testing and evidence-based standard-of-care treatment for hepatitis C virus infection among prisoners and PWUD39 and to address the high levels of non-communicable diseases among homeless people.3

Service design should be based on the fundamental principle of equity, whereby all protocols, guidelines and policies should provide all service users with the same access to medical products and technologies as everyone else, subject to need and according to the best standard of care that is locally available (D1; table 2).

Financing

Generally, healthcare interventions targeting underserved populations have been chronically underfunded and treated as short-term and isolated projects. Items in this section (table 3) underscore that services should be adequately and sustainably financed based on an accurate, up-to-date local needs assessment (E1) over a suitable timeframe (E2), together with suitable impact assessment.

Table 3.

Nobody Left Outside Service Design Checklist: sections E (financing) and F (leadership and governance)

| E. Financing Aim: ensure the service is adequately and sustainably resourced. Relevance: providers ✓ policymakers ✓✓ |

Yes | No | Not relevant/comments |

| E1. Are services adequately financed based on an accurate, up-to-date local needs assessment? | |||

| E2. Is the service sustainably financed for a suitable timeframe? | |||

| E3. Does service financing take an intersectoral perspective based on the needs of the community? |

| F. Leadership and governance Aim: ensure service is suitably led and governed, with community involvement. Relevance: providers✓ policymakers ✓✓ |

Yes | No | Not relevant/comments |

| F1. Are people from the target community involved in the leadership and governance of the service? | |||

| F2. Does the service reflect international standards regarding human rights, equity, non-discrimination and confidentiality? | |||

| F3. Is there a supportive legal framework and policy environment? | |||

| F4. Is there a National Action Plan regarding health and social care for the community, developed with involvement of the community? | |||

| F5. Is the service operated under the Health authorities (rather than the interior or justice authorities)? | |||

| F6. Do health and social services authorities, and relevant government agencies, collaborate in the delivery of the service? | |||

| F7. Does the service have accountable, transparent leadership and governance? |

Many states depend on donor funding to deliver some services targeting underserved groups, such as national HIV, viral hepatitis and tuberculosis programmes. Where donors have withdrawn support, it is vital that governments maintain equitable service delivery through sustainable health financing systems to avoid detrimental effects on public health.23 24

Health services for marginalised populations can be funded in a variety of ways, including by municipal, regional, national, European Union and international funding sources. In some instances, health can be funded through structural funds, which in the past have traditionally been associated with infrastructure. This would allow for fundamental change rather than short-term projects.

The value of investment in community-based services for underserved, marginalised people should be considered from an intersectoral perspective, that is, taking into account the broader benefits of such services on public health objectives and social/welfare services (E3). Multifaceted community-based services can facilitate early diagnosis and interventions that can reduce healthcare costs associated with some key public health threats while improving outcomes. In particular, providing access to routine primary care services has the potential to reduce the need for more expensive, unplanned emergency hospital care.

For example, harm reduction services to prevent blood-borne viruses are cost-effective.40 In England, it is estimated that preventing only 1% of HIV cases annually would save £15–19 million, while the annual costs of late HIV diagnosis are twice those of early diagnosis.41 Policies and investment into harm reduction can also deliver broader social benefits, such as lower levels of drug-related crime and reduced pressure on criminal justice systems.

Evidence also clearly indicates that housing assistance for homeless people benefits health service utilisation,27 42 although housing stability can cause an initial spike in healthcare use by allowing homeless people to properly connect with the health system. For example, housing interventions improve HIV care access and outcomes and can prevent new infections, supporting a role in primary prevention.27 Economic arguments also support the full provision of healthcare services for undocumented migrants, that is, in order to fulfil equity principles and health objectives and because timely provision of primary healthcare services is cost-saving over hospital care.6 43–45

Leadership and governance

Governance to accelerate UHC involves transparent, inclusive and equitable decision-making processes that allow for the input of all stakeholders and which develop policies that perform effectively, reaching clear and measurable outcomes for all, building accountability and being fair.1 The NLO Checklist (table 3) is intended to promote the involvement of people from target communities and/or community advocacy organisations in the planning, delivery, leadership and governance of services (F1), in general alignment with recommendations.6 7 9 26 Various strategies and tools can help empower community and patient populations towards this purpose.9 26 29 46

High-level political attention is needed to ensure that the appropriate legal frameworks are in place to support healthcare access for all. The rights of all individuals to access to preventive healthcare and to benefit from medical treatment under national laws and practices are enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union47 and other international instruments.48 49 Services should reflect international standards regarding human rights, equity, non-discrimination and confidentiality (F2). Inequities in healthcare access should be addressed as part of antidiscrimination and protective policies that foster a supportive legal framework and non-discriminatory policy environment (F3). A Joint UN statement has called for member states to review and repeal punitive laws proven to have negative health outcomes and that counter established public health evidence.36 Notably, in May 2019, the WHO adopted a 5-year global action plan aiming to achieve UHC and the highest attainable standard of health for refugees and migrants together with host populations,50 and G7 Health Ministers committed to improve healthcare access for all, including by strengthening primary healthcare.51

National disease-specific action plans are important to the achievement of SDGs, and yet remain absent in many European Union countries, have important gaps or frequently lack community involvement.39 Such national action plans are also important to tackle the broader deficits in access in step with issues such as housing and other health determinants (F4).

Accountable, transparent leadership and governance is essential (F7). The call by the WHO Regional Office for Europe for enhanced national and local stewardship for implementation of the strategies and action plans on migrant health,6 and the recommendations by a Lancet Commission for robust accountability and monitoring in the field of migrant health7 also apply to those for other marginalised communities. Notably, the 2018 Global Harm Reduction International study highlighted poor transparency on harm reduction funding across Europe.52

Discussion

Some of the people in Europe most in need of healthcare are among the least likely to receive it—this may be considered an extreme example of Tudor Hart's Inverse Care Law.53 To fulfil their commitment to contribute to the health and well-being of all and to reach the SDGs, governments at all levels—national, regional and local—working together with civil society partners should ensure that nobody is left outside of their health system. Inequalities in access are not inevitable and can be addressed by tailored, integrated service models. The NLO Service Design Checklist is offered as a practical tool to support this process based on the principles of equity, non-discrimination and community engagement.

Checklists have been successfully applied for clinical purposes in various settings. Notably, the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist has been associated with reductions in surgical mortality.54 The scope of our Checklist includes direct considerations for service designers and frontline providers, together with wider aspects of policy, funding and governance. It shares many common aspects with the WHO Checklist for the framework for action on integrated health services,19 including needs assessment, provision of a broad, multidisciplinary service, empowerment of target communities (ie, providing people with the necessary education, skills and resources they need to take control of their own health and to play an active role in defining problems, decision making and actions to manage their health), workforce support, evidence generation on performance and clear accountability. Our Checklist focuses on certain marginalised communities, like the UNAIDs Checklist for community engagement in the implementation of guidelines on the sexual and reproductive rights of women living with HIV55 and a Public Health England Checklist of questions for healthcare practitioners to consider when speaking to new migrant patients.56

The NLO Checklist was developed with particular attention to homeless people, PWUD, LGBTI people, prisoners, sex workers and undocumented migrants based on the expertise of participating community organisations. While the Checklist is broad in scope, it is designed to allow representatives of multiple marginalised groups that often intersect and face common access barriers to collaboratively inform service design. As such, the Checklist is not intended to be universally applicable, wholesale. Rather, it provides a range of considerations that may be used flexibly for diverse purposes and adapted (with translation when needed) to particular settings. By the same token, given its breadth and the commonality of many access barriers, we expect the Checklist to have applications beyond the specific aforementioned communities.

We encourage researchers and other stakeholders to triangulate the Checklist versus existing available documentation and best practices relevant to service design for target communities. Pilot studies are also necessary to evaluate the functionality of the Checklist in practice. NLO participant organisations have recently called on the European Commission to support a pilot programme to coordinate and evaluate implementations of the Checklist in the context of delivering UHC in Europe.57 NLO members are considering applications with their own communities while raising awareness of the Checklist to promote its use more broadly,57 now with the support of the NLO Goodwill Ambassador, former European Union Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, Vytenis Andriukatis. Users are invited to report their experience and to provide feedback via the NLO website (www.nobodyleftoutside.eu).

We believe the Checklist will be of use to health service policymakers, public health bodies, healthcare practitioner bodies and NGOs at all levels when developing, updating, monitoring or auditing national or regional service provision and action plans for target groups. It may also assist regional or local healthcare authorities, service managers and frontline professionals and peer support workers in the design, refinement or assessment of local services. The Checklist may also help community advocacy organisations to engage in service design and action plan formulation with the aforementioned bodies (proactively or via consultation processes) and in wider advocacy efforts to improve equitable access to health and support services.

Conclusion

The NLO Service Design Checklist is offered as a practical tool to help overcome inequalities in access to health and support services. We encourage health service policymakers, public health bodies, healthcare authorities, healthcare practitioner bodies, peer support workers and non-governmental organisations to use it when developing, updating or monitoring action plans and local services for target groups. It may also assist civil society in wider advocacy efforts to improve access among underserved communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Representatives of the following organisations participated in the Nobody Left Outside (NLO) initiative towards development of the Service Design Checklist: Africa Advocacy Foundation (DO); Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) (JVL is supported by a Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities Miguel Servet grant (Instituto de Salud Carlos III/ESF, European Union [CP18/00074]) and further acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through the “Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2019-2023” Programme (CEX2018-000806-S) and from the Government of Catalonia through the CERCA Programme); Correlation European Harm Reduction Network (ES and Roberto Perez Gayo); European AIDS Treatment Group (MC and Ann-Isabelle Von Lingen); European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (FS); Fiona Godfrey (formerly European Association for the Study of the Liver, now independent public health consultant); Hepatitis C Trust (Rachel Halford); International Committee on the Rights of Sex Workers in Europe (Luca Stevenson); International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association Europe (Sophie Aujean and Katrin Hugendubel); Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (Alyna Smith).

Footnotes

Twitter: @JVLazarus

Contributors: All authors participated in the idea development, planning and creation of the NLO Service Design Checklist at NLO meetings and review cycles, including at the European Health Forum in Gastein. JVL and LB led the drafting of this paper. JVL and FS led a European Commission Thematic Network webinar to discuss the Checklist. All authors reviewed and contributed to each draft and approved the final draft.

Funding: The NLO initiative is supported financially by MSD. JVL, MC, DO, ES, ACS, FS and the individuals listed under ‘Acknowledgements’ participated in the NLO initiative on a volunteer (ie, non-remunerated) basis.

Competing interests: JVL reports research grants from AbbVie, Gilead and MSD, outside of the submitted work. LB is an employee of Interel (Brussels, Belgium), which received fees from MSD as part of the grant supporting the NLO initiative.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.United Nations Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 12 December 2012: 67/81. Global health and foreign policy, 2013. Available: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/67/81 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 2.World Health Organization Universal health coverage (UHC) website. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc) [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 3.Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet 2014;384:1529–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet 2011;377:956–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2018;391:241–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Report on the health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European region. No public health without refugee and migrant health, 2018. Available: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/392773/ermh-eng.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 7.Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, et al. The UCL-Lancet Commission on migration and health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet 2018;392:2606–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Health, rights and drugs. Harm reduction, decriminalization and zero discrimination for people who use drugs, 2019. Available: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/JC2954_UNAIDS_drugs_report_2019 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 9.World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Global Network of Sex Work Projects, The World Bank Implementing comprehensive HIV/STI programmes with sex workers: practical approaches from collaborative interventions, 2013. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/90000/9789241506182_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 10.Alencar Albuquerque G, de Lima Garcia C, da Silva Quirino G, et al. Access to health services by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: systematic literature review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2016;16:2 10.1186/s12914-015-0072-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joint Action on HIV and Co-infection Prevention and Harm Reduction (HA-REACT) An assessment of barriers to access to HIV and HCV services for people who inject drugs in Europe, 2019. Available: https://www.aidsactioneurope.org/en/publication/assessment-barriers-access-hiv-and-hcv-services-people-who-inject-drugs-europe [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 12.Luchenski S, Maguire N, Aldridge RW, et al. What works in inclusion health: overview of effective interventions for marginalised and excluded populations. Lancet 2018;391:266–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31959-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nobody Left Outside Thematic Network Joint statement: improving healthcare access for marginalised people, 2019. Available: https://nobodyleftoutside.eu/wp-content/uploads/NLO_Joint_Statement_08_01_2020_V2.2crop.pdf [Accessed 10 Feb 2019].

- 14.Onyango D, Schatz E, Lazarus JV. Taking a ‘people-centred’ approach to improving access to health care for underserved communities in Europe. Eurohealth 2017;23:23–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webinar presentation, 16 May NLO service design checklist – first webinar of the thematic network led by Nobody Left Outside platform (NLO), 2019. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/policies/videos/20190516_en.mp4 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 16.Lazarus JV, Cascio M, Halford R, et al. Nobody Left Outside (NLO) checklist: improving access to healthcare for vulnerable and underserved groups. Int J Integr Care 2019;19:507 10.5334/ijic.s3507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schatz E. Nobody Left Outside: practical guidance and policy solutions to promote equity of access for vulnerable and underserved communities to integrated health and social services, including addiction care. Lisbon addictions 2019, 23–25 October, Lisbon. Eposter 1011. Available: https://www.lisbonaddictions.eu/lisbon-addictions-2019/presentations/nobody-left-outside-practical-guidance-and-policy-solutions-promote-equity-access [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 18.World Health Organization Everybody business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action, 2007. Available: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 19.World Health Organization Strengthening people-centred health systems in the WHO European region: framework for action on integrated health services delivery, 2016. Available: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/315787/66wd15e_FFA_IHSD_160535.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 20.World Health Organization Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations, 2016. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246200/9789241511124-eng.pdf;jsessionid=01DC589F5EADDA2DD6E298ADC09B4301?sequence=1 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020]. [PubMed]

- 21.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Strategy and action plan for refugee and migrant health in the WHO European region, 2016. Available: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/314725/66wd08e_MigrantHealthStrategyActionPlan_160424.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 22.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Action plan for the health sector response to viral hepatitis in the WHO European region, 2017. Available: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/357236/Hepatitis-9789289052870-eng.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 23.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe Action plan for the health sector response to HIV in the WHO European region, 2017. Available: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/357478/HIV-action-plan-en.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 24.Day E, Hellard M, Treloar C, et al. Hepatitis C elimination among people who inject drugs: challenges and recommendations for action within a health systems framework. Liver Int 2019;39:20–30. 10.1111/liv.13949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) The next generation of health reforms: ministerial statement, 2017. Available: http://www.oecd.org/health/ministerial/ministerial-statement-2017.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 26.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, International Network of People Who Use Drugs, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Population Fund, World Health Organization, United States Agency for International Development Implementing comprehensive HIV and HCV programmes with people who inject drugs: practical guidance for collaborative interventions, 2017. Available: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2017_HIV-HCV-programmes-people-who-inject-drugs_en.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 27.Baxter AJ, Tweed EJ, Katikireddi SV, et al. Effects of housing first approaches on health and well-being of adults who are homeless or at risk of homelessness: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019;73:379–87. 10.1136/jech-2018-210981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith AC, Krieger C, Siciarek M. The role of cities in the integration of migrants: facilitating access to healthcare for all. Chapter 6 in: Villa M, editor. Global cities and integration. A challenge for the future. Milan: ISPI; 2018. P. 129–154. Available: https://www.ispionline.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/globalcities_web.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 29.World Health Organization One-To-One peer support by and for people with lived experience. WHO QualityRights guidance module. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329591/9789241516785-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 30.Nikolopoulos GK, Chanos S, Tsioptsias E, et al. HIV incidence among men who have sex with men at a community-based facility in Greece. Cent Eur J Public Health 2019;27:54–7. 10.21101/cejph.a4856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girometti N, McCormack S, Devitt E, et al. Evolution of a pre-exposure prophylaxis (PreP) service in a community-located sexual health clinic: Concise report of the PrEPxpress. Sex Health 2018;15:598–600. 10.1071/SH18055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jego M, Abcaya J, Ștefan D-E, et al. Improving health care management in primary care for homeless people: a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:E309 10.3390/ijerph15020309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization WHO guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. Geneva; WHO, 2019. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311941/9789241550505-eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020]. [PubMed]

- 34.Shrestha R, Altice FL, DiDomizio E, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of an mHealth-based approach as an HIV prevention strategy among people who use drugs on pre-exposure prophylaxis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2020;14:107–18. 10.2147/PPA.S236794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernández-Gutiérrez M, Bas-Sarmiento P, Poza-Méndez M. Effect of an mHealth intervention to improve health literacy in immigrant populations: a quasi-experimental study. Comput Inform Nurs 2019;37:142–50. 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joint United Nations statement on ending discrimination in health care settings Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Food Programme (WFP), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), et al, 2017. Available: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/ending-discrimination-healthcare-settings_en.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 37.Saracino A, Lorenzini P, Lo Caputo S, et al. Increased risk of virologic failure to the first antiretroviral regimen in HIV-infected migrants compared to natives: data from the ICONA cohort. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22:288.e1–8. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saracino A, Zaccarelli M, Lorenzini P, et al. Impact of social determinants on antiretroviral therapy access and outcomes entering the era of universal treatment for people living with HIV in Italy. BMC Public Health 2018;18:870 10.1186/s12889-018-5804-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lazarus JV, Stumo SR, Harris M, et al. Hep-CORE: a cross-sectional study of the viral hepatitis policy environment reported by patient groups in 25 European countries in 2016 and 2017. J Int AIDS Soc 2018;21:e25052 10.1002/jia2.25052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson DP, Donald B, Shattock AJ, et al. The cost-effectiveness of harm reduction. Int J Drug Policy 2015;26:S5–11. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Resource impact report: HIV testing: increasing uptake among people who may have undiagnosed HIV (NG60), 2016. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng60/resources/resource-impact-report-pdf-2727796141 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 42.Lee CT, Winquist A, Wiewel EW, et al. Long-term supportive housing is associated with decreased risk for new HIV diagnoses among a large cohort of homeless persons in New York City. AIDS Behav 2018;22:3083–90. 10.1007/s10461-018-2138-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trummer U, Novak-Zezula S, Renner A-T, et al. Cost analysis of health care provision for migrants and ethnic minorities. Vienna: Equi-Health, 2015. Available: https://eea.iom.int/sites/default/files/publication/document/Cost_analysis_of_health_care_provision_for_irregular_migrants_and_EU_citizens_without_insurance.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 44.Bozorgmehr K, Razum O. Effect of restricting access to health care on health expenditures among asylum-seekers and refugees: a quasi-experimental study in Germany, 1994-2013. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131483. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Cost of exclusion from healthcare. The case of migrants in an irregular situation, 2015. Available: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2015-cost-healthcare_en.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 46.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, Ferrer L . Engaging patients, carers and communities for the provision of co-ordinated/integrated health services: strategies and tools, 2015. Available: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/290443/Engaging-patients-carers-communities-provision-coordinated-integrated-health-services.pdf [Accessed 20 Mar 2020].

- 47.European Commission Charter of fundamental rights of the European Union (2012C 326/02), 2012. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:12012P/TXT [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 48.World Medical Association WMA resolution on refugees and migrants. adopted by the 67th World Medical Assembly, Taipei, Taiwan, 2016. Available: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-resolution-on-refugees-and-migrants/ [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 49.United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Duties of states towards refugees and migrants under the International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights, 2017. Available: http://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=4slQ6QSmlBEDzFEovLCuW1AVC1NkPsgUedPlF1vfPMJbFePxX56jVyNBwivepPdlEe4%2BUb4qsdJhuBDpCRSOwCXPjZ7VN7SXN0oRoXkZhCuB9Z73iyU35LZveUjX0d7u [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 50.World Health Organization Promoting the health of refugees and migrants. Draft global action plan 2019–2023. 72nd World health assembly, 2019. Available: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_25Rev1-en.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 51.G7 Health Ministers Ensuring access to health for all, 2019. Available: https://www.elysee.fr/admin/upload/default/0001/05/59c3454ab28edc451be46e846b70dc38a532db95.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 52.Stone K, Shirley-Beavan S. Global State of Harm Reduction 2018. London: Harm Reduction International, 2018. Available: https://www.hri.global/global-state-harm-reduction-2018 [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 53.Tudor Hart J. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971;297:405–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.GlobalSurg Collaborative Pooled analysis of who surgical safety checklist use and mortality after emergency laparotomy. Br J Surg 2019;106:e103–12. 10.1002/bjs.11051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.International Community of Women Living with HIV Latina, Sophia, Eurasian Women’s Network on AIDS, International Community of Women Living with HIV West Africa, MENA Rosa, International Community of Women Living with HIV & AIDS Eastern Africa Translating community research into global policy reform for national action: a checklist for community engagement to implement the who consolidated guideline on the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV (3rd edition), 2018. Available: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/who_srhr_guideline_checklist_en.pdf [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 56.Public Health England Assessing new patients from overseas: migrant health guide, 2019. Available: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/assessing-new-patients-from-overseas-migrant-health-guide#checklist-for-new-migrant-patients [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 57.Lazarus JV, Onyango D, Spinnewijn F. Leaving nobody outside our healthcare systems–in Europe or elsewhere. BMJ opinion 25 November, 2019. Available: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2019/11/25/leaving-nobody-outside-our-healthcare-systems-in-europe-or-elsewhere/ [Accessed 10 Feb 2020].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.