Abstract

Background

Although disparities in the use of healthcare services in the United States have been well-documented, information examining sociodemographic disparities in the use of healthcare services (for example, office-based and emergency department [ED] care) for nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions is limited.

Questions/purposes

This study was designed to answer two important questions: (1) Are there identifiable nationwide sociodemographic disparities in the use of either office-based orthopaedic care or ED care for common, nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions? (2) Is there a meaningful difference in expenditures associated with these same conditions when care is provided in the office rather than the ED?

Methods

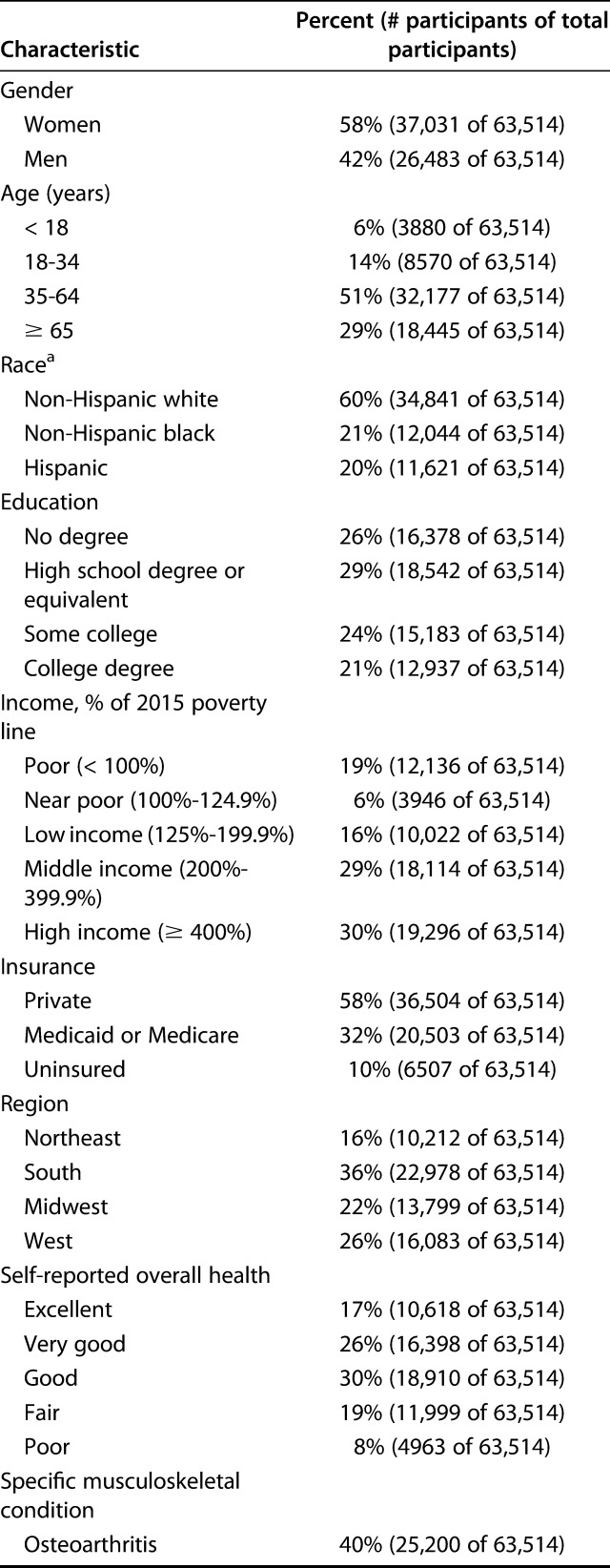

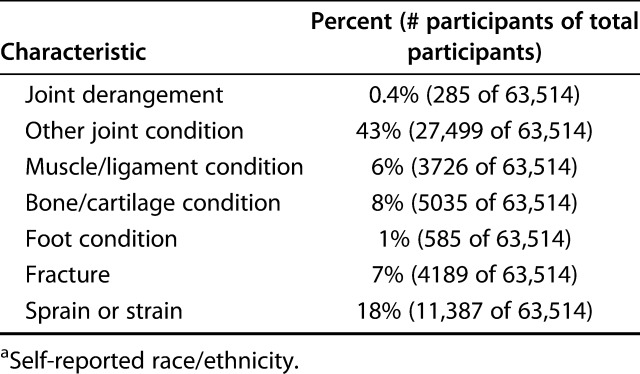

This study analyzed data from the 2007 to 2015 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). The MEPS is a nationally representative database administered by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality that tracks patient interactions with the healthcare system and expenditures associated with each visit, making it an ideal data source for our study. Differences in the use of office-based and ED care were assessed across different socioeconomic and demographic groups. Healthcare expenditures associated with office-based and ED care were tabulated for each of the musculoskeletal conditions included in this study. The MEPS database defines expenditures as direct payments, including out-of-pocket payments and payments from insurances. In all, 63,514 participants were included in our study. Fifty-one percent (32,177 of 63,514) of patients were aged 35 to 64 years and 29% were older than 65 years (18,445 of 63,514). Women comprised 58% (37,031 of 63,514) of our population, while men comprised 42% (26,483 of 63,514). Our study was limited to the following eight categories of common, nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions: osteoarthritis (40%, 25,200 of 63,514), joint derangement (0.5%, 285 of 63,514), other joint conditions (43%, 27,499 of 63,514), muscle or ligament conditions (6%, 3726 of 63,514), bone or cartilage conditions (8%, 5035 of 63,514), foot conditions (1%, 585 of 63,514), fractures (7%, 4189 of 63,514), and sprains or strains (18%, 11,387 of 63,514). Multivariable logistic regression was used to ascertain which demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related factors were independently associated with differences in the use of office-based orthopaedic services and ED care for musculoskeletal conditions. Furthermore, expenditures over the course of our study period for each of our musculoskeletal categories were calculated per visit in both the outpatient and the ED settings, and adjusted for inflation.

Results

After controlling for covariates like age, gender, region, insurance status, income, education level, and self-reported health status, we found substantially lower use of outpatient musculoskeletal care among patients who were Hispanic (odds ratio 0.79 [95% confidence interval 0.72 to 0.86]; p < 0.001), non-Hispanic black (OR 0.77 [95% CI 0.70 to 0.84]; p < 0.001), lesser-educated (OR 0.72 [95% CI 0.65 to 0.81]; p < 0.001), lower-income (OR 0.80 [95% CI 0.73 to 0.88]; p < 0.001), and nonprivately-insured (OR 0.85 [95% CI 0.79 to 0.91]; p < 0.001). Public insurance status (OR 1.30 [95% CI 1.17 to 1.44]; p < 0.001), lower income (OR 1.53 [95% CI 1.28 to 1.82]; p < 0.001), and lesser education status (OR 1.35 [95% CI 1.14 to 1.60]; p = 0.001) were also associated with greater use of musculoskeletal care in the ED. Healthcare expenditures associated with care for musculoskeletal conditions was substantially greater in the ED than in the office-based orthopaedic setting.

Conclusions

There are substantial sociodemographic disparities in the use of office-based orthopaedic care and ED care for common, nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions. Because of the lower expenditures associated with office-based orthopaedic care, orthopaedic surgeons should make a concerted effort to improve access to outpatient care for these populations. This may be achieved through collaboration with policymakers, greater initiatives to provide care specific to minority populations, and targeted efforts to improve healthcare literacy.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders are a major disease burden in the United States, affecting a greater number of Americans than either cardiovascular or respiratory disease and accounting for an estimated USD 162.4 billion in healthcare expenditures between 2012 and 2014 [2, 9]. Despite efforts to curtail this burden, both the prevalence and expense of musculoskeletal diseases are on the rise [2, 30]. As such, there is an increasing need to ensure that patients with musculoskeletal conditions have adequate access to and understand the appropriate use of healthcare services.

Outpatient orthopaedic care for musculoskeletal conditions has been shown to result in equal clinical outcomes and reduced costs when compared with similar care delivered in the inpatient or emergency setting [6, 8, 17, 19]. Outpatient care may therefore serve as the most appropriate avenue to address a subset of musculoskeletal complaints. However, recent studies in the fields of neurology and dermatology suggest that there may be substantial disparities in access to and use of outpatient care for patients across a wide array of sociodemographic groups [25, 29]. There is reason to believe similar disparities exist within the realm of musculoskeletal care. For example, patients belonging to minority groups have lower utilization rates for total joint arthroplasty and lower screening rates for osteoporosis, and publicly insured or uninsured patients have lower access to outpatient orthopaedic care [5, 13, 23, 27, 28]. However, whether sociodemographic disparities exist in the use of outpatient versus emergency department (ED) care for common and nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions has not been well characterized. Determining whether such disparities exist is of interest to orthopaedic surgeons, who are uniquely poised to improve healthcare for patients with musculoskeletal conditions while helping reduce healthcare expenditures [18].

We therefore asked (1) Are there identifiable nationwide sociodemographic disparities in the use of either office-based orthopaedic care or ED care for common, non-emergent musculoskeletal conditions? (2) Is there a meaningful difference in expenditures associated with these same conditions when care is provided in the office rather than in the ED?

Patients and Methods

Data Source and Population

This study analyzed data from the 2007 to 2015 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). The MEPS represents the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population and is administered annually by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The MEPS uses a stratified random sampling procedure to select participants, who are followed for 2 years. Additionally, to our knowledge, this is the only survey that tracks patient interactions with the healthcare system and the expenditures associated with each visit. The MEPS database suggests that patients should be analyzed anew each year, and that each year is nationally representative and can be analyzed individually. Five questionnaires are administered to participants during that time using computer-assisted personal interviewing. The MEPS also verifies participant responses and collects supplemental information, including visit dates, diagnosis and procedure codes, and payments by contacting medical providers and pharmacies by telephone. More detail on the survey structure of the MEPS can be found elsewhere [1].

The MEPS database assigns each specialty a code that allows tracking of patients across interactions with physicians for their musculoskeletal problems. For each MEPS year, we linked demographic, medical condition, and event files to determine the number of office-based outpatient orthopaedic visits made by each individual with a self-reported musculoskeletal condition.

Participants

We included eight common musculoskeletal conditions that can be treated in an office-based setting. We excluded conditions in which there would be substantial overlap with other specialties. For example, we excluded musculoskeletal conditions that affect the spine, as these patients may receive their medical care from neurosurgeons. The eight musculoskeletal conditions in our analysis were categorized using the ICD-9-CM, the disease classification system available at the time of data collection, and included osteoarthritis (ICD-9-CM codes 715, 716), joint derangement (718), other joint conditions (719), muscle or ligament conditions (728), bone or cartilage conditions (733), foot conditions (734, 735), fractures (812, 814, 815, 816, 818, 822, 825, 826), and sprains or strains (840, 842, 843, 844, 845, 847, 848). Importantly, only conditions considered nonemergent were included in our analysis to avoid bias. For example, a patient who had a hip fracture in a given survey year is likely to go to the ED for their acute care. However, this visit is necessary because many hip fractures are considered an emergency and should be treated in the hospital setting. Thus, patients with hip fractures, femur fractures, tibia fractures, all dislocations, and trauma diagnoses were excluded from the study. A participant was considered to have a musculoskeletal condition if they self-reported one or more of the nonemergent conditions described above at any point during the survey year.

MEPS event data were reported as the diagnosis for which patients sought care at the ED or in an office. For instance, a patient who had a wrist fracture in a given survey year would visit either the ED or an office for acute care. Subsequently, the patient may have had follow-up visits in an office or the ED, and those visits would count towards where they sought their outpatient care.

Description of Experiment, Treatment, or Surgery

For each individual, we only tabulated the number of ED visits due to one of the eight musculoskeletal conditions as described by the provider-identified ICD-9-CM codes. For outpatient office-based orthopaedic care, we assumed the visit was for the documented musculoskeletal condition. We then sub-classified these visits by individual condition and race. The total expenditure, which MEPS defines as out-of-pocket payments and payments made by private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, and other sources, was recorded for each office visit and ED visit. All expenditures reported are restricted to outpatient care from orthopaedic surgeons or emergency department care for the conditions included in our analysis. Therefore, the expenditures we report do not include any expenditure associated with surgery or rehabilitation/physical therapy, even when these services are clinically indicated. All costs were adjusted to 2015 USD using the consumer price index for all urban consumers [4].

Variables, Outcome Measures, Data Sources, and Bias

We compared outpatient orthopaedic use and per-capita costs across a number of demographic and socioeconomic factors. The age of participants was categorized as younger than 18 years, 18 to 34 years, 35 to 64 years, or 65 years and older. Respondent race was described by the MEPS as either non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, or mixed race and thus was maintained for this study. Participants were then asked to choose one or more of these options to self-identify their race/ethnicity. Asian and mixed-race respondents were excluded from our analysis because of their relative scarcity in the MEPS, resulting in wide CIs for these groups. Individual incomes were categorized as either poor (< 100% of the federal poverty line), near poor (100%-124% of the federal poverty line), low income (125%-199% of the federal poverty line), middle income (200%-399% of the federal poverty line), or high income (> 399% of the federal poverty line). Education was classified as having completed high school or the general education diploma, some college, bachelor’s degree or higher, or having no degree. Insurance status was described as either private, public, or uninsured, and geographic areas of residence were categorized as the Northeast, South, Midwest, and West. Self-reported health status was measured on a five-point scale: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor.

The MEPS survey population included 315,216 participants surveyed for any medical condition between 2007 and 2015. At the time of the survey, 63,514 participants had one or more of the eight musculoskeletal conditions included in our study. Fifty-one percent (32,177 of 63,514) of participants included in this study were between the ages of 35 and 64, and 29% (18,445 of 63,514) were older than 65 years. Women comprised 58% (37,031 of 63,514) of our population, while men comprised 42% (26,483 of 63,514). The prevalence of each diagnosis was as follows: osteoarthritis (40%, 25,200 of 63,514), joint derangement (0.4%, 285 of 63,514), other joint conditions (43%, 27,499 of 63,514), muscle or ligament conditions (6%, 3726 of 63,514), bone or cartilage conditions (8%, 5035 of 63,514), foot conditions (1%, 585 of 63,514), fractures (7%, 4189 of 63,514), and sprains or strains (18%, 11,387 of 63,514) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics of the 63,514 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey participants who self-reported a musculoskeletal condition, unweighted, 2007 to 2015

Statistical Analysis, Study Size

We constructed a logistic regression model to ascertain which demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related factors were independently associated with differences in the use of office-based orthopaedic services and differences in the use of ED services. Furthermore, we calculated expenditures over the course of our study period for each included musculoskeletal condition per visit in both the outpatient and ED settings, and we adjusted for inflation. The binary outcome variable was based on whether participants with a musculoskeletal condition made zero or one or more orthopaedic surgeon office visits during the year they were surveyed. Expenditures data was interpreted using a Wilcoxon and rank sum analysis, which compares median expenditures. Annual averages and percentages were adjusted to represent the noninstitutionalized civilian population of the United States using the MEPS’s person-level weights, which reflect adjustments for survey nonresponse and adjustments to population control total. Furthermore, the MEPS does not collect data using simple random sampling, therefore, to account for the complex sampling of the MEPS all standard errors were estimated using the R “survey” package (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria), which bases calculations on person-level weights, clustering, and stratification data [20]. More detail on these procedures can be found elsewhere [25]. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant, and all statistical analyses were performed using R (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Independent Predictors of Receipt of Office-based Orthopaedic Care for Musculoskeletal Conditions

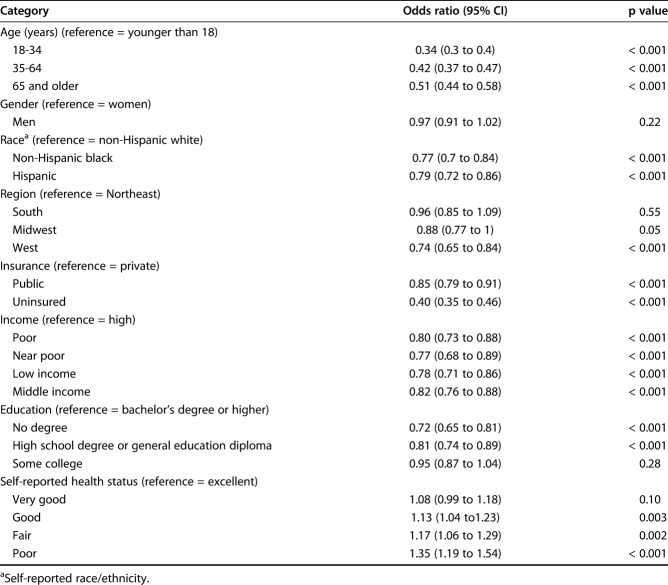

After controlling for all covariates in our model (age, gender, race/ethnicity, geographic region, insurance status, income, education, and self-reported health status), we found substantial differences in the use of office-based orthopaedic care across several sociodemographic groups. Both patients who were Hispanic (odds ratio 0.79 [95% confidence interval 0.72 to 0.86]; p < 0.001) and non-Hispanic black (OR 0.77 [95% CI 0.70 to 0.84]; p < 0.001) were overall less likely to receive office-based orthopaedic care than patients who were non-Hispanic white for the eight categories of common, nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions included in our study. Patients age 65 and older (OR 0.51 [95% CI 0.44 to 0.58]; p < 0.001) were less likely to receive office-based orthopaedic care than younger patients. Patients with public insurance (OR 0.85 [95% CI 0.79 to 0.91]; p < 0.001) and uninsured patients (OR 0.40 [95% CI 0.35 to 0.46]; p < 0.001) were less likely to use office-based orthopaedic care than privately insured patients. Patients with income below the federal poverty line (OR 0.80 [95% CI 0.73 to 0.88]; p < 0.001) were less likely to receive an office-based orthopaedic visit than high-income patients. Patients without a degree (OR 0.72 [95% CI 0.65 to 0.81]; p < 0.001) were less likely to use office-based orthopaedic care than those with a bachelor’s degree or higher (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socioeconomic and demographic factors independently associated with receipt of any office-based orthopaedic care in survey year, weighted, 2007 to 2015

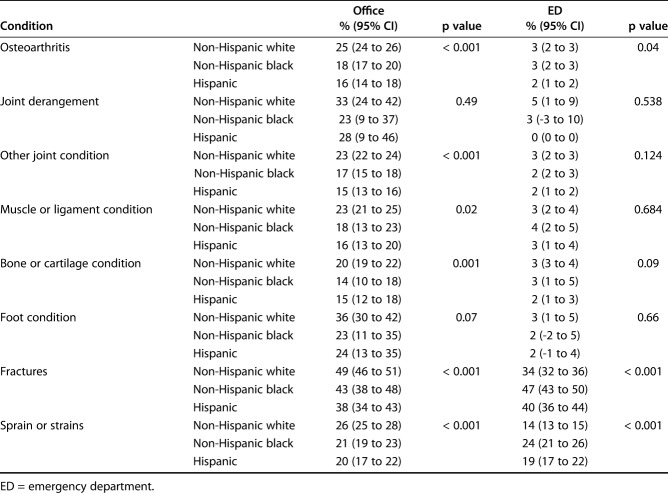

When racial/ethnic differences in office-based orthopaedic care utilization were examined by category of condition, we found that patients who were Hispanic and non-Hispanic black were less likely to receive office-based orthopaedic care than patients who were non-Hispanic white for osteoarthritis (16% [95% CI 14 to 18] Hispanic versus 18% [95% CI 17 to 20] non-Hispanic black versus 25% [95% CI 24 to 26] non-Hispanic white; p < 0.001), other joint conditions (15% [95% CI 13 to 16] versus 17% [95% CI 15 to 18] versus 23% [95% CI 22 to 24]; p < 0.001), muscle or ligament conditions (16% [95% CI 13 to 20] versus 18% [95% CI 13 to 23] versus 23% [95% CI 21 to 25]; p = 0.02), bone or cartilage conditions (15% [95% CI 12 to 18] versus 14% [95% CI 10 to 18] versus 20% [95% CI 19 to 22]; p = 0.001), fractures (38% [95% CI 34 to 43] versus 43% [95% CI 38 to 48] versus 49% [95% CI 46 to 51]; p < 0.001), and sprains or strains (20% [95% CI 17 to 22] versus 21% [95% CI 19.2 to 23.3] versus 26% [95% CI 25 to 28]; p < 0.001) (Table 3). No such difference was observed for joint derangement and foot conditions.

Table 3.

Percent of patients with each musculoskeletal condition who received office-based or ED care for their musculoskeletal condition, subclassified by race

Independent Predictors of Receipt of Emergency Department Care for Musculoskeletal Conditions

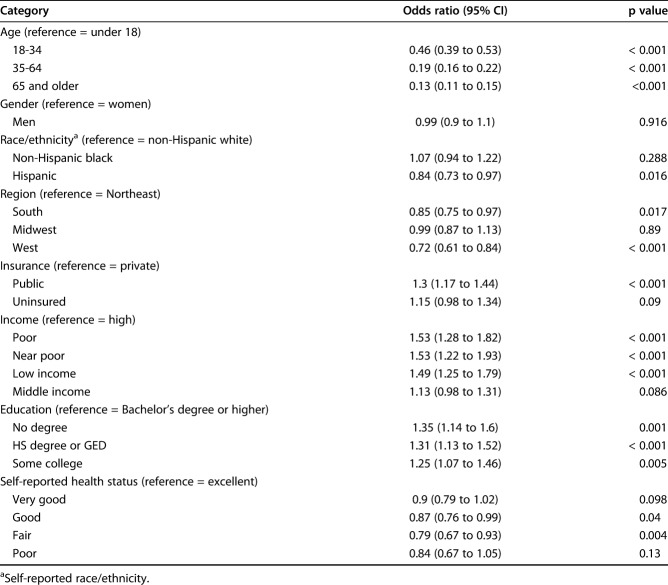

After controlling for all covariates in our model (age, gender, race/ethnicity, geographic region, insurance status, income, education, and self-reported health status), we found substantial differences in the use of the ED care for musculoskeletal care across several sociodemographic groups. Hispanic patients (OR 0.84 [95% CI 0.73 to 0.97]; p = 0.016) were overall less likely to receive ED care than non-Hispanic white patients for the common, nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions included in our study, but non-Hispanic black patients were not (OR 1.07 [95% CI 0.94 to 1.22]; p = 0.288) (Table 4). Publicly insured patients (OR 1.3 [95% CI 1.17 to 1.44]; p < 0.001) were more likely to use the ED for musculoskeletal care than privately insured patients, but uninsured patients were not (OR 1.15 [95% CI 0.98 to 1.34). Patients with an income below the federal poverty line (OR 1.53 [95% CI 1.28 to 1.82]; p < 0.001) were more likely to receive musculoskeletal care in the ED than patients with high income. Patients without a degree (OR 1.35 [95% CI 1.14 to 1.6]; p < 0.001) were more likely to use the ED for musculoskeletal care than those with a bachelor’s degree or higher. Patients age 65 or older (OR 0.13 [95% CI 0.11 to 0.15]; p < 0.001) were less likely to use the ED for musculoskeletal care than younger patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Socioeconomic and demographic factors independently associated with receipt of any emergency room care for a musculoskeletal complaint in survey year, weighted, 2007-2015

When we examined racial/ethnic differences in ED use according to category of condition, we found that patients who were Hispanic were less likely to receive ED care for osteoarthritis (2% [95% CI 1 to 2] versus 3% [95% CI 2 to 3] for patients who were non-Hispanic black versus 3% [95% CI 2 to 3] for patients who were non-Hispanic white; p = 0.04). However, patients who were Hispanic and non-Hispanic black were more likely to receive ED care compared with patients who were non-Hispanic white for fractures (40% [95% CI 26 to 44] versus 47% [95% CI 42 to 50] versus 34% [95% CI 32 to 36]; p < 0.001) and sprains or strains (19% [95% CI 17 to 22] versus 24% [95% CI 21 to 26] versus 14% [95% CI 13 to 15]; p < 0.001). No such difference was observed for joint derangement, other joint conditions, muscle or ligament conditions, bone or cartilage conditions, and foot conditions (Table 3).

Per Visit Expenditure for Each Musculoskeletal Condition in both Office and ED Settings

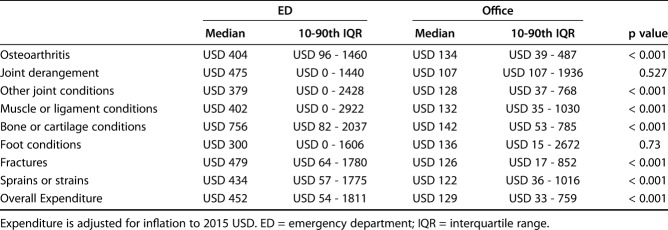

Median healthcare expenditure for the eight categories of musculoskeletal conditions included in this study was substantially greater in the ED than in the office-based orthopaedic setting (ED median: USD 452 [10-90th percentile interquartile range {IQR}: USD 54 – USD 1811] versus office median: USD 129 [IQR USD 33 – USD 759]; p < 0.001). For osteoarthritis, median expenditure in the ED was USD 404 [IQR USD 96 - USD 1460] versus median expenditure of USD 134 [IQR USD 39 – USD 487] in the office-based orthopaedic setting (p < 0.001). For other joint conditions, median expenditure in the ED was USD 379 [IQR USD 0 – USD 2428] versus USD 128 [IQR USD 37 – USD 768] in the office (p < 0.001). For muscle or ligament conditions, median expenditure in the ED was USD 402 [IQR USD 0 – USD 2922] versus USD 132 [IQR USD 35 – USD 1030] in the office (p < 0.001). For bone or cartilage conditions, median expenditure in the ED was USD 756 [IQR USD 82 – USD 2037] versus USD 142 [IQR USD 53 – USD 785] in the office (p < 0.001). For fracture, median expenditure in the ED was USD 479 [IQR USD 64 – USD 1780] versus USD 126 [IQR USD 17 – USD 852] in the office (p < 0.001). For sprains or strains, median expenditure in the ED was USD 434 [IQR USD 57 – USD 1775] versus USD 122 [IQR USD 36 – USD 1016] in the office (p < 0.001). No meaningful differences in healthcare expenditure were observed for joint derangement (ED median USD 475 [IQR USD 0 – USD 1440] versus office median USD 107 [IQR USD 107 – USD 1937]; p = 0.527) or foot conditions (ED median USD 300 [IQR USD 0 – USD 1606] versus office median USD 136 [IQR USD 15 – USD 2672]; p = 0.73) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Annual healthcare expenditure associated with musculoskeletal conditions in the ED and office-based orthopaedic settings from 2007-2015

Discussion

Sociodemographic disparities in access to and use of healthcare are well-established [10, 14, 15, 21, 22, 26]. Within the realm of musculoskeletal care, minorities have been shown to have lower use of total joint arthroplasty and lower screening numbers for osteoporosis, and patients without private insurance have been shown to have lower access to outpatient orthopaedic care [5, 13, 23, 27, 28]. However, whether additional sociodemographic disparities exist in the use of outpatient and ED care for nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions is not well characterized. Such disparities are important to identify because outpatient care is associated with equal clinical outcomes, equal or greater patient satisfaction, and reduced cost compared with similar services provided in an inpatient or emergency setting [6, 8, 17, 19]. In the present study, we highlight substantially lower use of outpatient musculoskeletal care among patients who are minorities, lesser-educated, lower-income, and non-privately-insured, even after controlling for all other covariates. Public insurance status, lower income, and lesser education status were also associated with greater use of musculoskeletal care in the ED. Furthermore, we found that healthcare expenditures associated with outpatient care were lower than those for ED care across all categories of musculoskeletal conditions included in this study.

There are limitations to this study. Although our work documented the disparities present in the use of office-based orthopaedic care and ED care for common, nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions, we were unable to elucidate the cause of these disparities. It is likely that the underlying cause of these differences is multifactorial. Patients and families may have differing levels of health literacy and differing beliefs and attitudes toward health and disease, or they may not have the social support and resources to recognize diseases and make informed decisions. For example, patients who have undergone total joint arthroplasty may not have received the proper education to know what symptoms warrant an ED visit or an office visit [7,12, 24]. Further, the MEPS represents the US non-institutionalized population and excludes people living in nursing homes, prisons, and other institutional settings. Despite these exclusions, however, MEPS represents the vast majority of Americans, and data from this study can reliably be applied to orthopaedic practices across the nation. The MEPS collects data through patient report, which may be affected by recall bias; however, all visits and diagnoses are verified with providers, which improves the validity and accuracy of the data within the MEPS database. Additionally, limitations to the diagnostic coding used in the survey did not allow us to definitively say that a patient receiving outpatient orthopaedic care was doing so for their documented musculoskeletal condition. However, each condition that a participant had was considered a separate entry, allowing the authors to assume they were receiving care for their documented condition. Furthermore, diagnostic coding did not allow us to assess orthopaedic conditions such as chronic pain, the care of which may overlap with other specialists, restricting the scope of our analysis. The conditions that we able to include, however, encompassed a large portion of patients with musculoskeletal conditions. Further, the data regarding spinal diagnoses that we gathered (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A297) demonstrates a similar trend to the one presented here. Therefore, the authors believe that the findings here are generalizable to most nonemergent musculoskeletal conditions, despite the inability to include them in a single study.

Another limitation of this study is an inability to distinguish between the day on which patients receive musculoskeletal care. For example, it is certainly appropriate for patients to present to the ED rather than the office with a common musculoskeletal complaint on a weekend night. However, the authors assumed that the frequency of such visits on weekend nights should not change as a function of sociodemographic characteristics and that patients in this situation would be encouraged to receive appropriate outpatient follow-up. Although this is an important limitation to acknowledge, the authors feel that it should not affect the study’s primary outcome. Another potential limitation lies within the difference in diagnostic reliability of the two sources of care studied. For example, a very plausible scenario can occur where patient A goes to the ED for an injury and receives the diagnosis of joint derangement, while patient B is seen in the office and receives the diagnosis of ACL tear. However, the authors feel comfortable assuming that patients who received a diagnosis of joint derangement in the ED would either (1) visit an orthopaedic surgeon in the office-based setting for further management, where they would receive a more appropriate diagnosis, or (2) return to the ED due to exacerbation of their condition. The authors actually consider this to be a consequence of access to care and therefore feel it is an important aspect of our study design rather than a limitation. Furthermore, the present study examined disparities in the use of office-based orthopaedic care. Some patients may have received their initial care through a primary care physician, and thus are not included in our analysis. However, this confounding factor is likely small. Because of a combination of uncertainty in expertise and experience as well as a lack of availability, many patients who present to their primary care physician for orthopaedic care are eventually referred to an orthopaedic surgeon and would be captured by our study [31]. Furthermore, if an issue with access prevents a patient from seeing an orthopaedic surgeon, the patient may then present to the ED for musculoskeletal care, and would still be included in the study. Finally, the limited sample size of the survey did not allow us to include in the analysis other racial minority groups, many of whom may be subject to the same disparities in the use of orthopaedic outpatient care as are patients who are black and Hispanic patients.

Our findings demonstrate that patients who are Hispanic and non-Hispanic black use less office-based musculoskeletal care than their non-Hispanic white counterparts, which further supports the findings already demonstrated within the total joint population. A large Medicare-based study demonstrated that the annual rate for knee arthroplasty was higher in both non-Hispanic white women and non-Hispanic white men than it was for their counterparts who were Hispanic or black. This finding held true across nearly every geographical region in the United States [27]. A subsequent study using Medicare patient data found that even after controlling for age, sex, and income, black men, Hispanic men, Asian men, and Asian women all had lower TKA proportions, as well as access to care, than their counterparts who were white males [28]. In both studies, the authors point to issues of affordability and accessibility as primary drivers of racial disparities in undergoing TKAs. These issues of access likely play a role in the present study as well. Additionally, it has been suggested that patients who are minorities are often dissatisfied with outpatient care, in part because of poor communication, lack of physician relationship, and distrust [3]. Therefore, issues with communication and implicit bias may also affect the use of office-based musculoskeletal care.

We report that patients who are publicly insured (Medicare and Medicaid) and uninsured have lower use of office-based musculoskeletal care than their privately insured counterparts. This finding adds to, and is generally concordant with, other studies showing that patients who are publicly insured and uninsured are less likely to be seen by local orthopaedic surgeons [5] and, consequently, must travel greater distances to receive outpatient orthopaedic care compared with patients with private insurance [13, 23]. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that, in one study, 44% of patients who were publicly insured or uninsured were unable to travel to tertiary referral centers for their orthopaedic care due to limitations in personal resources, resulting in higher no-show rates to outpatient appointments [5]. Further, we found that patients who are publicly insured have greater ED use for musculoskeletal care compared with their counterparts who are privately insured, which may reflect greater access for these patients to the ED than to outpatient orthopaedic offices. This finding is consistent with a recent report showing that patients on Medicaid are substantially more likely to visit the ED for treatment of both low-severity and high-severity conditions compared with patients who are privately insured [16]. Strategies to minimize these differences in outpatient and ED use by insurance status may involve improved reimbursement for orthopaedic care delivered to patients who are publicly insured or further expansion of Medicaid coverage. Medicaid expansion in Missouri, for example, led to an increase in use of total joint arthroplasty between 2013 and 2016, and there is reason to believe that a similar effect may be observed in the outpatient and ED settings [11]. Future studies should therefore assess the impact of these strategies on use of office-based orthopaedic and ED care for musculoskeletal conditions.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated disparities in outpatient orthopaedic care in the United States and elucidated the economic burden that results. In the present study, we highlight substantially lower use of outpatient orthopaedic care for patients who are minorities, less educated, low income, publicly insured, and uninsured, even after controlling for all other covariates. Many of these same characteristics were also associated with greater ED care use, including being publicly insured, having low income, and having less education. Healthcare expenditure associated with musculoskeletal care delivered in the ED was substantially greater than that associated with office-based orthopaedic care for the musculoskeletal conditions included in this study. It is imperative for orthopaedic surgeons to continue to collaborate with policy makers to create targeted interventions that improve access to and use of outpatient orthopaedic care to reduce healthcare expenditures. Furthermore, orthopaedic surgeons should focus on improving communication with patients of all backgrounds to help them identify musculoskeletal symptoms that warrant office-based orthopaedic care versus ED care. Future studies should evaluate the impact of these and similar strategies on reducing disparities in use of outpatient orthopaedic care and ED care for musculoskeletal conditions.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

The first two authors contributed equally to the creation of this manuscript.

Each author certifies that he has no commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his institution waived approval for the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, OH, USA.

References

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Survey MEP. Survey Background. 2009. Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/survey_back.jsp. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- 2.Bone and Joint Initiative. The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS). Rosemont, IL2014. Available at: http://www.boneandjointburden.org/. Accessed November 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks TR. Pitfalls in communication with Hispanic and African American patients: do translators help or harm? J Natl Med Assoc . 1992;84:941-947 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor. Archived Consumer Price Index Detailed Reports. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables/detailed-reports/home.htm. Accessed January 1, 2019.

- 5.Calfee RP, Shah CM, Canham CD, Wong AH, Gelberman RH, Goldfarb CA. The influence of insurance status on access to and utilization of a tertiary hand surgery referral center. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:2177-2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhary MA, Lange JK, Pak LM, Blucher JA, Barton LB, Sturgeon DJ, Koehlmoos T, Haider AH, Schoenfeld AJ. Does orthopaedic outpatient care reduce emergency department utilization after total joint arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:1655-1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clement RC, Derman PB, Graham DS, Speck RM, Flynn DN, Levin LS, Fleisher LA. Risk factors, causes, and the economic implications of unplanned readmissions following total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:7-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford DC, Li CS, Sprague S, Bhandari M. Clinical and cost implications of inpatient versus outpatient orthopedic surgeries: a systematic review of the published literature. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2015;7:6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Research & Scientific Affairs, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Physician Visits for Musculoskeletal Symptoms and Complaints. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/stats/patientstats.asp . Accessed June 10, 2019.

- 10.Dunlop DD, Song J, Manheim LM, Chang RW. Racial disparities in joint replacement use among older adults. Med Care. 2003;41:288-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dy CJ, Brown DS, Maryam H, Keller MR, Olsen MA. Two-state comparison of total joint arthroplasty utilization following Medicaid expansion. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:619-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felix HC, Seaberg B, Bursac Z, Thostenson J, Stewart MK. Why do patients keep coming back? Results of a readmitted patient survey. Soc Work Health Care. 2015;54:1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Froelich JM, Beck R, Novicoff WM, Saleh KJ. Effect of health insurance type on access to care. Orthopedics. 2013;36:e1272-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoaglund FT, Oishi CS, Gialamas GG. Extreme variations in racial rates of total hip arthroplasty for primary coxarthrosis: a population-based study in San Francisco. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:107-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz BP, Freund DA, Heck DA, Dittus RS, Paul JE, Wright J, Coyte P, Holleman E, Hawker G. Demographic variation in the rate of knee replacement: a multi-year analysis. Health Serv Res. 1996;31:125-40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim H, McConnell KJ, Sun BC. Comparing emergency department use among Medicaid and commercial patients using all-payer all-claims data. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20:271-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krywulak SA, Mohtadi NG, Russell ML, Sasyniuk TM. Patient satisfaction with inpatient versus outpatient reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: a randomized clinical trial. Can J Surg. 2005;48:201-206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C, Watts B, Litaker D. Access to and utilization of healthcare: the provider’s role. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2006;6:653-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovald ST, Ong KL, Malkani AL, Lau EC, Schmier JK, Kurtz SM, Manley MT. Complications, mortality, and costs for outpatient and short-stay total knee arthroplasty patients in comparison to standard-stay patients. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:510-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lumley T. Analysis of Complex Survey Samples: R Foundation; 2018. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survey/survey.pdf. Accessed January 1, 2019.

- 21.Mahomed NN, Barrett J, Katz JN, Baron JA, Wright J, Losina E. Epidemiology of total knee replacement in the United States Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1222–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McBean AM, Gornick M. Differences by race in the rates of procedures performed in hospitals for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev. 1994;15:77-90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson BM, Draeger RW, Olsson EC, Spang JT, Lin FC, Kamath GV. A regional assessment of medicaid access to outpatient orthopaedic care: the influence of population density and proximity to academic medical centers on patient access. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paxton EW, Inacio MCS, Singh JA, Love R, Bini SA, Namba RS. Are there modifiable risk factors for hospital readmission after total hip arthroplasty in a US healthcare system? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3446-3455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saadi A, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Mejia NI. Racial disparities in neurologic health care access and utilization in the United States. Neurology. 2017;88:2268-2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh JA, Lu X, Rosenthal GE, Ibrahim S, Cram P. Racial disparities in knee and hip total joint arthroplasty: an 18-year analysis of national Medicare data. Ann Rheum Dis . 2014;73:2107-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skinner J, Weinstein JN, Sporer SM, Wennberg JE. Racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in rates of knee arthroplasty among Medicare patients. NEJM . 2003;349:1350-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skinner J, Zhou W, Weinstein J. The influence of income and race on total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2159-2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, Scott JF, Bordeaux JS. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the united states. JAMA Dermatol. 2018. 1;154:1286-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinstein SL. The burden of musculoskeletal conditions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolf AD. What healthcare services do people with musculoskeletal conditions need? The role of rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:281-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]