Abstract

Purpose:

Subjective memory complaints (SMCs) have been shown to be associated with lower neuropsychological test scores cross-sectionally. However, it remains unclear if such findings hold true for African American (AA) older adults.

Methods:

Baseline visit data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center database collected from September 2005 through March 2018 were used. Generalized linear mixed models specifying binomial distributions were used to examine how neuropsychological test scores affect the likelihood of reporting SMCs.

Patients:

Inclusion criteria were participants who reported AA as their primary race, 60–80 years of age, were cognitively unimpaired, and had a Mini-Mental Status Exam ≥26. 1021 older AA adults without missing data met the criteria.

Results:

258 participants reported a SMC. SMCs were more likely with lower scores on measures of episodic memory and processing; however, SMCs were also more likely with higher scores on a measure of working memory. Working memory appeared to mediate reporting of SMC among participants with lower episodic memory scores.

Discussion:

These findings demonstrate that SMCs are associated with lower scores on objective neuropsychological measures among older AAs. Additional work is needed to determine if SMCs are further associated with a risk for clinical transition to mild cognitive impairment or dementia among AA older adults.

Keywords: African americans, cognitive aging, neuropsychological tests, self report, logistic models

Introduction

Subjective memory complaints (SMCs) are self-reported perceptions of declines in memory ability from a previous level of function. The clinical utility of SMCs in the diagnosis of memory decline is unclear. Further, the association between SMC and changes in objective memory evaluation also remains in question. SMCs may be a significant diagnostic tool in the evaluation of older adults at risk for memory problems when considered in tandem with objective results of a neuropsychological test battery (NTB). For example, in one longitudinal study, at the time of the first SMC reported, persons who later progressed to dementia had lower memory test scores than those who were never impaired 1. However, among older African Americans (AAs), some prior studies have found associations between SMCs and objective NTB performance 2,3 whereas others have found no association 4–7. Interestingly, older AAs are also less likely to report a SMC 8,9. Taken together, what implications do these findings hold for the predictive and diagnostic utility of SMC on memory decline in AA older adults?

Additionally, other factors are known to affect the reporting of SMCs among older AAs, including heightened cerebrovascular disease risk 10, medication regiment 11, and depression 11–14. Although some prior studies have accounted for the above factors that might confound or obscure a relationship between SMC and NTBs, others have not accounted for some other less studied variables that could influence reporting SMCs. For example, it may be important to consider the referral source of 15 and family history of memory problems among 16 participants in an investigation of SMC reporting.

The variability in the methodology and results of the current literature presents an opportunity for further exploration and clarification. The present study aims to examine the relationship between SMC and NTB results in a national sample of older AAs. Data collected as part of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) longitudinal study 17 was used to obtain a standardized NTB from a large sample of AA older adults from sites throughout the USA. NACC sites record referral source, family history of memory problems, and presence of SMC. The NACC data offers the opportunity to examine the association between SMCs and objective cognitive testing measures, while accounting for family history and referral source, and other factors shown to effect SMC reporting. It is hypothesized that there will not be a significant association between SMCs and NTB results due to the relatively low probability that AA will report SMC.

Methods

Participants

Data was derived from the NACC database and included cross-sectional data collected at the baseline visit of participants in a longitudinal observational study of aging at 34 Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) throughout the USA from September 2005 through a March 2018 database block. The following inclusionary criteria were applied: participants (1) reported African American as their primary race, (2) were between the ages of 60–80, (3) had a consensus diagnosis of cognitively unimpaired (i.e., using the term “normal” to evaluate the association of SMCs in relation to cognitive performance without the confound of a clinical cognitive disorder that might predispose to anosognosia), and (4) had a Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) score ≥26. The data collection procedures were approved by the IRBs of each of the institutions comprising the NACC consortium.

NACC provided the baseline data of 1614 African Americans who were cognitively intact. Applying inclusion criteria for age and MMSE reduced the sample to 1233 and then to 1107, respectively. As is described below, we tried to derive or impute missing values when workable. However, 86 participants were excluded due to unavailable values for one or more of the following: medication count (n = 11), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; n = 24), education (n = 3), or various NTB subtests (n = 54). Compared to those without missing data, participants excluded due to missing data were slightly older (M = 71.7, SD = 5.14) and reported fewer medications (M = 3.74, SD = 4.44), ps < 0.01, but did not differ on age, education, GDS, and cerebrovascular risk factors. They were also more likely to report a history of hypertension (n = 70), p = 0.04, but did not significantly differ on reporting a SMC, primary care provider (PCP) as referral source, family history, informant memory concerns, or sex. This left 1021 cognitively intact, African American older adults for the analysis.

Procedures

Participants underwent a medical evaluation including a review of health history, physical neurological exam, semi-structured clinical interviews, and neuropsychological testing in accordance to procedures at ADCs. The procedures and specific data elements collected have been described previously 17.

Variables

Age and education are described as integers in years. The GDS was used to assess the symptoms or severity of depression 18. The score for the item “Do you feel that you have more problems with memory than most?” was subtracted from the GDS to avoid potential re-measurement of the variable. Therefore, the adjusted GDS score range was 0 to 14, with higher values indicating greater depressive symptomology. The Hachinski ischemia scale was used to determine cerebrovascular risk on a range of 0 to 10 19, with higher values indicating greater risk. For 26 participants with unavailable Hachinski scores, a surrogate score was imputed along Hachinski criteria using medical history data on stroke or TIA and hypertension, and clinician data for mode of onset of cognitive symptoms (i.e., stepwise or abrupt). The count of all medications was used as a surrogate of chronic health status. Additionally, an indicator of which ADC was the data collection site was included to account for possible variation between sites.

Subjective Memory Complaint

SMC was a dichotomous variable derived from responding “yes” to either the memory-specific item on the GDS or in self-report recorded by the clinician. If one of the values were missing, the one available was used to derive SMC.

Adjustments for Potential Confounds Inherent in Reporting SMCs

Several variables were included to control for factors other than objective memory performance that could influence the likelihood of reporting a SMC. Self-reporting a family history of dementia or memory problems was treated as a three-level variable (yes/no/unknown) because this data was unavailable for 111 participants. Rather than exclude these 111 from the analysis, it was decided to create the “unknown” category. Referral sources for enrollment in the study were classified in the raw data from NACC as “health care provider”, “self, relative, or friend”, “other”, or “unknown”. Because the variable was a proxy for the influence PCP support can exert on participation it was dichotomized into “PCP” and “other” for the analysis. Results were unchanged if the raw referral source variable was used (not shown). Motivation for visiting the clinic was dichotomized as “to participate in a research study” or “to have a clinical evaluation and participate in research”.

Neuropsychological Testing

The NTB 20 included the MMSE measuring general cognitive functioning, the Logical Memory test of immediate and delayed recall, Digit Span Forward and Backward to measure attention and working memory, animals and vegetables to assess language, and the Boston Naming Test to also assess language. Trail Making Test A and B were used as measures of processing speed and executive functioning, and Digit Symbol was a measure of processing speed and executive functioning. All test scores were converted to z-scores adjusted for age, sex, and education using established norms 21.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using R 3.5.5 console 22–25. T-tests and chi-square tests were used to compare continuous and nominal participant characteristics, respectively, with respective effect sizes of Cohen’s D and Cramer’s V̄. ANOVAs (with Tukey’s adjustment) and chi-square pairwise comparisons were used to compare characteristics between sources within SMC reporters. Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs), specifying binomial distributions were used to examine likelihood of reporting a SMC, which was the dependent variable. Backward elimination was done with the GLMERSelect() function of the StatisticalModels package to identify NTB subtests related to reporting a SMC. To start, all NTB subtests were fixed effects and data collection site was a random effect (i.e., participant characteristics were not included). At each stage in the backwards elimination procedure, the fixed effect with the highest p-value > 0.05 was dropped; p-values determined with likelihood ratio tests. NTB subtests remaining after the backwards elimination procedure were included in the final model as fixed effects along with age, sex, education, GDS, medication count, Hachinski, family history, enrollment reason, and referral source, and NACC data collection site as a random effect. All continuous fixed effects were centered at their mean, except for NTB z-scores, which remained as z-scores. Terms for the GDS interaction with education and sex were considered in the model because they could account for some variability in reporting SMC 26 but were not included due to null effects (ps > 0.46). Significance of the random effect was tested by comparing the deviance of the final model to a model without it.

Results

Table 1 contains demographic characteristics of 1021 participants; of which, 763 denied SMC and 258 reported SMC. Participants with a SMC reported significantly more depressive symptoms (p < 0.001), and were more likely to have been referred by their PCP (p = 0.03), have a reliable informant report concerns for their memory (p < 0.001), and report a family history of dementia (p = 0.03) as compared to those participants who did not report SMC.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| No SMC |

SMC |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Variables | M | SD | M | SD | d | 95% CI |

| Age | 70.058 | 5.340 | 70.411 | 5.203 | 0.067 | −0.07, 0.21 |

| Education | 14.747 | 2.837 | 14.337 | 3.033 | 0.142 | 0.00, 0.28 |

| Adjusted-GDS | 0.895 | 1.531 | 1.678 | 2.228 | 0.452 | 0.31, 0.60 |

| Medication Count | 5.028 | 3.888 | 5.112 | 4.232 | 0.021 | −0.12, 0.16 |

| Hachinski | 0.877 | 0.787 | 1.093 | 1.281 | 0.231 | 0.09, 0.37 |

| Discrete Variables | % | n | % | n | 95% CI | |

| Male | 0.210 | 160 | 0.213 | 55 | 0.004 | 0.00, 0.07 |

| Hypertension in Histrory | 0.719 | 538 | 0.728 | 179 | 0.008 | 0.00, 0.07 |

| Family History Reported | 0.448 | 342 | 0.535 | 138 | 0.083 | 0.03, 0.10 |

| Family History Unavailable | 0.098 | 75 | 0.105 | 27 | ||

| Enrolled to Have Evaluation | 0.121 | 92 | 0.112 | 29 | 0.011 | 0.00, 0.07 |

| Referral Source was PCP | 0.062 | 47 | 0.101 | 26 | 0.066 | 0.01, 0.14 |

| Informant Concerns | 0.035 | 25 | 0.253 | 62 | 0.331 | 0.26, 0.40 |

Note: Bolded effect sizes have p < 0.05. Adjusted-GDS is the sum of the 15-item GDS mins the “Do you have more problems with memory than most?” item. GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale. SMC = subjective memory complaint. PCP = primary care provider.

Shown in Table 2 are means and SDs for NTB subtests. Participants reporting SMCs scored significantly below those without SMCs on tests of memory, verbal fluency, and executive function.

Table 2.

Neuropsychological Test Battery Raw Means and SDs, and Standardized Score Means

| No SMC |

SMC |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | MRaw | SD | MZ | MRaw | SD | MZ | d | 95% CI |

| Mini-Mental Status Exam | 28.64 | 1.24 | 0.31 | 28.58 | 1.31 | 0.31 | 0.002 | −0.14, 0.14 |

| Logical Memory Immediate | 12.09 | 3.43 | 0.04 | 11.06 | 3.60 | −0.19 | 0.252 | 0.11, 0.39 |

| Logical Memory Delay | 10.71 | 3.75 | 0.10 | 9.40 | 3.92 | −0.17 | 0.290 | 0.15, 0.43 |

| Logical Memory Delay Intervala | 21.95 | 7.33 | 23.88 | 7.77 | 0.261 | 0.12, 0.40 | ||

| Digit Span Forward Correct | 8.14 | 1.99 | −0.28 | 7.83 | 1.95 | −0.39 | 0.115 | 0.03, 0.26 |

| Digit Span Forward Long | 6.53 | 1.07 | −0.24 | 6.39 | 1.08 | −0.33 | 0.099 | 0.04, 0.24 |

| Digit Span Backward Correct | 5.86 | 2.07 | −0.31 | 5.79 | 1.92 | −0.30 | 0.009 | −0.13, 0.15 |

| Digit Span Backward Long | 4.40 | 1.16 | −0.31 | 4.41 | 1.14 | −0.26 | 0.056 | −0.09, 0.20 |

| Animals | 17.54 | 4.82 | −0.47 | 16.43 | 4.68 | −0.63 | 0.187 | 0.05, 0.33 |

| Vegetables | 14.36 | 3.81 | 0.97 | 13.27 | 3.71 | 0.73 | 0.229 | 0.09, 0.37 |

| Trail Making Test A | 42.98 | 19.70 | −0.69 | 44.05 | 18.86 | −0.72 | 0.024 | 0.12, 0.17 |

| Trail Making Test B | 119.12 | 61.87 | −0.77 | 130.53 | 65.67 | −0.96 | 0.152 | 0.01, 0.29 |

| Digit Symbol | 42.25 | 11.02 | −0.08 | 39.76 | 11.21 | −0.25 | 0.182 | 0.04, 0.32 |

| Boston Naming | 25.24 | 4.01 | −0.91 | 24.28 | 4.77 | −1.18 | 0.199 | 0.06, 0.34 |

Note: Effect sizes were computed using z-scores adjusted for age, sex, and education using formulae from Shrick et al. (2011). Bolded ds have ps < 0.05. SMC = Subjective Memory Complaint.

Participants reporting a SMC had lower Logical Memory Delay scores than those without SMC when analyzing only participants with a delay interval ≥ 23min.

SMC was reported in one of three ways: only to the attending clinician in 62.7% of subjects reporting an SMC, only during the GDS (17.4%), or both to the clinician and during the GDS (19.8%). Participants reporting SMCs to both the clinician and during the GDS reported significantly higher depressive symptoms (F[2, 255] = 9.88; ps < 0.02), were more likely to have enrolled for an evaluation (χ2 = 7.8, p = 0.02), and were more likely to have an informant corroborate their SMC (χ2 = 12.4, p = 0.002). The group that reported SMCs in both settings also exhibited higher performance on Digit Span Backward correct (F[2, 255] = 3.34, ps < 0.16) and Boston Naming (F[2, 255] = 3.53, ps < 0.05). No other demographic or neuropsychological test variables differed between the SMC source groups.

The backwards elimination procedure yielded three NTB subtests that significantly predicted reporting a SMC: Logical Memory (LM; χ2 = 13.0, p < 0.001), Digit Span Backward longest span (DSBL; χ2 = 5.47, p = 0.02), and Digit Symbol (DS; χ2 = 65, p = 0.02). Animal fluency (p = 0.07) and MMSE (p = 0.06) approached significance but were eliminated before the final stage of the backwards elimination procedure. For all other NTB subtests, ps were > 0.18.

The final model (shown in Table 3) was computed with SMC as the dependent variable. It included LM, DSBL, and DS as fixed effects along with participant characteristics and the variables that could potentially effect reporting a SMC, with NACC site as a random effect. Inspection of standardized residual plots indicated 56 participants with values >|2|; the findings were essentially unchanged if data from these 56 participants were excluded (not shown). As performance on LM delayed recall (p < 0.001) and DS (p = 0.05) declined, the likelihood of reporting a SMC increased. Interestingly, SMCs were more likely to be reported as DSBL increased (p = 0.03)—that is, SMCs were more likely when working memory capacity was greater. Summarily, these findings suggest that there is a relationship between the subjective experience of memory problems and performance on objective assessments of cognition among AA older adults. Additionally, higher GDS scores (p < 0.001) and cerebrovascular risk (p = 0.03) significantly increased the likelihood of reporting a SMC, as did reporting a family history of dementia (p = 0.05). The effect of having the PCP as a referral source approached significance (p = 0.08). Other variables were not significant predictors of SMC.

Table 3.

Generalized Linear Mixed Model Predicting Subjective Memory Complaints

| Fixed Effects | Coef. | SE | z | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.373 | 0.195 | −5.057 | 0.000 | 0.250 | 0.550 |

| Age | 0.984 | 0.016 | −1.018 | 0.309 | 0.953 | 1.015 |

| Male | 0.752 | 0.211 | −1.349 | 0.177 | 0.494 | 1.134 |

| Education | 0.969 | 0.028 | −1.095 | 0.273 | 0.917 | 1.025 |

| Adjusted-GDS | 1.220 | 0.043 | 4.653 | 0.000 | 1.122 | 1.328 |

| Medication Count | 1.006 | 0.022 | 0.267 | 0.790 | 0.963 | 1.050 |

| Hachiniski | 1.193 | 0.084 | 2.097 | 0.036 | 1.012 | 1.410 |

| Enrolled to Have Evaluation | 1.206 | 0.288 | 0.649 | 0.516 | 0.678 | 2.114 |

| Referral Source was PCP | 1.690 | 0.300 | 1.751 | 0.080 | 0.926 | 3.026 |

| Family History Not Reported | 0.704 | 0.166 | −2.111 | 0.035 | 0.507 | 0.975 |

| Family History Unavailable | 0.857 | 0.275 | −0.560 | 0.575 | 0.493 | 1.460 |

| Logical Memory Delay | 0.690 | 0.092 | −4.042 | 0.000 | 0.575 | 0.825 |

| Digit Span Backward Long | 1.202 | 0.086 | 2.151 | 0.031 | 1.016 | 1.424 |

| Digit Symbol | 0.833 | 0.091 | −2.006 | 0.045 | 0.696 | 0.996 |

| Random Effects | SD | ICC | X2 | p | 95% CI | |

| NACC Site | 1.986 | 0.125 | 27.627 | 0.000 | 1.532 | 2.901 |

Note: Values for coefficients and 95% CIs have been exponentiated from raw output; i.e., they can be read in the table as odd ratios. GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale. ICC = intraclass correlation. NACC = National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. PCP = Primary care provider.

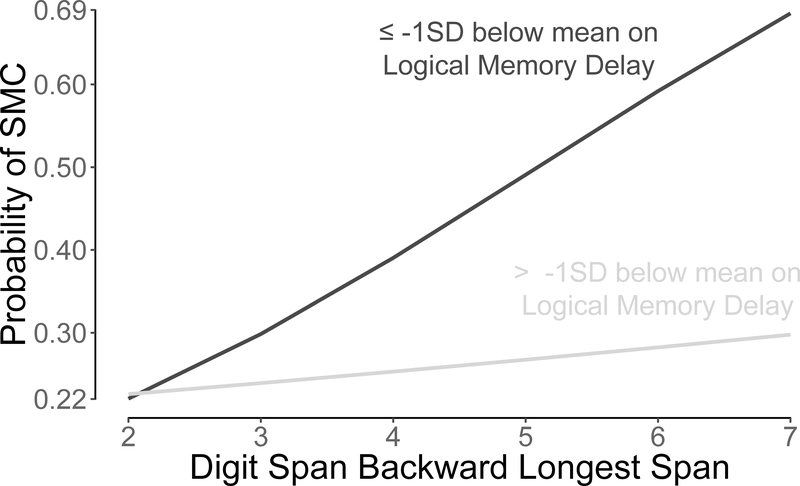

A post-hoc analysis was conducted to examine the finding that higher working memory capacity increased the likelihood of reporting a SMC. Participants were split into two groups whether they were above (n = 885) or at/below (n = 136) LM delay z-score cut-off of −1 (i.e., 1 SD below age-, sex-, and education-adjusted mean). A cutoff of −1 was used instead of −1.5 due to the potential clinical relevance of individuals who may be trending toward memory impairment. LM delay z-score replaced in the final model with this variable. To facilitate interpretation, the DSBL z-score was replaced with the raw DSBL score. The final model was recomputed including an interaction term between the dichotomous LM variable and the raw DSBL score. The interaction was borderline significant (p = 0.06), and the model was otherwise essentially unchanged (see Supplementary Table 1). The interaction indicated that in the presence of objective memory deficits, participants with higher working memory capacity tended to be more likely to report SMC than those with lower working memory. However, for participants without objective memory deficits, the effect of working memory on a SMC was minimal (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Probability of reporting a Subjective Memory Complaint (SMC) as a function of Logical Memory delayed recall and Digit Span Backward longest span. Participants whose delayed recall performance approached an impaired range (i.e., < −1 SD) were more likely to report a SMC when they had higher working memory capacities. However, for participants whose delayed recall was in an unimpaired range, reporting a SMC was unrelated to working memory capacity.

Discussion

The study demonstrates a significant association between SMCs and objective measures of cognitive function in AA older adults. Overall, performance on a variety of neuropsychological tests was significantly associated with reports of SMCs at baseline enrollment into the national longitudinal cohort. This association was evident even when controlling for data collection site, referral source, family history of dementia, reason for enrolling in research, and other demographic characteristics known to affect SMC reporting.

Specifically, performance on LM delayed recall, DS, and DSBL were significantly associated with SMC. The retention of LM delay on the final model is rather intuitive because it was the measure of memory and prior research has reported this as well 3. The retention of DS also makes sense, as it has been reported by others 3 and is often found to be an early indicator of future cognitive impairment 27. These findings are in contrast with several studies that reported null associations between SMCs and NTB performance which may be due to methodological differences, nonresponse, or other sampling characteristics. Importantly though, our findings are in line with 3, who reported that among a large, community sample of AAs, SMCs were associated with lower composite scores in the domains of episodic memory (including LM delay) and processing speed (including DS). Given the results of two studies using large, unique samples and comprehensive NTBs there is strong evidence of a relationship between SMCs and NTB performance among older AAs in the domains of episodic memory and processing speed.

However, there is an interesting and unexpected finding of the present study that higher performance on DSBL increased the likelihood of reporting SMCs. A post hoc analysis suggests that among participants at or nearing impaired ranges on memory testing (i.e., on LM delay), those with greater working memory capacity (i.e., on DSBL) were more likely to report a SMC. The cause of this unclear. It could be related to associations between personality traits and working memory 28 or perhaps due to overlapping neural correlates of self-awareness and DSB performance 29–33. Although speculative, these hypothetical causes can be tested in future studies. Altogether, further research is needed to understand the clinical utility of SMCs among AA older adults at risk for cognitive impairments.

Secondarily, the present study provides further evidence that cerebrovascular disease risk 10, depression 11–14, and having a family history of memory problems 16 contribute to the reporting of SMCs among AAs. There was also a trend effect on SMC reporting of having a PCP as the referral source. AAs have traditionally expressed distrust towards the healthcare systems and clinical research, due in part to a history of malpractice in relation to healthcare and research conduct 34. Despite the challenging history between AAs and the medical and research establishments, only a small amount of research has been conducted to examine the prevalence of SMCs reported by AA older adults to their PCPs. Future studies would benefit from examining these concepts in greater depth. Additionally, PCPs and researchers should collaborate to harmonize a person’s experience transitioning from medical practice to a research study, ensuring effective and ethical recruitment strategies, and that patients fully understand their due rights in the research setting.

Several limitations of the present study should be considered. First, the NACC cohort is not a random sample of older AAs in USA, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Although the prevalence of NACC SMCs may not be representative of SMCs among AAs in the general public, it is arguable that the underlying neurocognitive mechanisms would not be dramatically different in unsampled segments of the population. Thus, the associations between NTBs and SMCs are likely not spurious. Also, several variables that effect the report of SMCs were controlled for in the model in an attempt to reduce sampling bias. However, socioeconomic status (SES) and literacy are not routine data collection elements in the NACC UDS and could not be controlled for in the analysis. Further work including considerations of an area deprivation index (ADI), that could be computed in aggregate by NACC which collects the first three zip code digits, and composites of SES should be pursued. This would provide additional insight about confounds of racial/ethnic status and sociocultural status on NTB performance 7,35,36.

Likewise, literacy has been shown to account for AA disparities in NTB performance 37 and the findings of the present study should be interpreted cautiously as we do not have data sufficient to control for this confound. The absence of literacy data could be addressed by NACC in that the majority of ADCs collect site-specific data that includes one of the widely used brief assessments of reading ability (e.g., Wide Range Achievement Test or North American Reading Test).

One final limitation recognized by the authors is that due to the dichotomous nature of the SMC variable; participants endorsed either having a concern about their memory or not. Added variance in SMCs might be explained by NTBs if SMCs were measured using an instrument that yielded a continuous value or measured subjective cognitive concerns beyond memory. Despite this limitation, the data presented clearly demonstrates that participants who reported a SMC did have lower scores on memory testing and were more likely to have an informant have concerns for their memory.

A major strength of the study is the large sample of AA older adults that is both systematically well characterized and geographically diverse. The use of a standardized NTB (the UDS) and the uniform acquisition of data on SMCs allow insight into the clinical importance of SMCs in AA older adults. It also shows the broad generalizability given the geographic diversity from which the sample was derived.

In summary, the present data clearly demonstrates that SMCs are associated with lower cognitive test scores cross-sectionally. If older AAs are at a higher risk of developing further memory problems due to a neurodegenerative process, findings of the current study suggest that SMCs may be a useful diagnostic tool coupled with the results of an NTB. Additional work is needed to determine if such SMCs are further associated with the risk for a clinical cognitive transition to mild cognitive impairment or dementia in an AA older adult population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers for their insightful commentary that led to a stronger product. We also thank Dr. Erin Abner and Dr. Richard J. Kryscio for their guidance in study design and analysis. Gratitude is paid also to the personnel at ADCs and at NACC. We are grateful for research participants and their close others for volunteering their time.

Statement of support: The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI Robert Vassar, PhD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kryscio R, Abner E, Jicha G, et al. Self-reported memory complaints: a comparison of demented and unimpaired outcomes. The journal of prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. 2016;3(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazargan M, Bazargan S. Self-reported memory function and psychological well-being among elderly African American persons. Journal of Black Psychology. 1997;23(2):103–119. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Fleischman DA, et al. Memory complaints, dementia, and neuropathology in older blacks and whites. Annals of neurology. 2018;83(4):718–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDougall GJ. Memory self-efficacy and memory performance among black and white elders. Nursing Research. 2004;53(5):323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amariglio RE, Townsend MK, Grodstein F, Sperling RA, Rentz DM. Specific subjective memory complaints in older persons may indicate poor cognitive function. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(9):1612–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sims RC, Whitfield KE, Ayotte BJ, Gamaldo AA, Edwards CL, Allaire JC. Subjective memory in older African Americans. Experimental aging research. 2011;37(2):220–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson JD, Rentz DM, Aghjayan SL, et al. Subjective cognitive concerns are associated with objective memory performance in Caucasian but not African-American persons. Age and ageing. 2017;46(6):988–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abner E, Kryscio R, Caban-Holt A, Schmitt F. Baseline subjective memory complaints associate with increased risk of incident dementia: the PREADVISE trial. The journal of prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. 2015;2(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blazer DG, Hays JC, Fillenbaum GG, Gold DT. Memory complaint as a predictor of cognitive decline: a comparison of African American and White elders. Journal of Aging and Health. 1997;9(2):171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sperling SA, Tsang S, Williams IC, Park MH, Helenius IM, Manning CA. Subjective Memory Change, Mood, and Cerebrovascular Risk Factors in Older African Americans. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology. 2017;30(6):324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazargan M, Barbre AR. Self‐reported memory problems among the Black elderly. Educational Gerontology: An International Quarterly. 1992;18(1):71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill NL, Mogle J, Bhargava S, et al. Differences in the Associations Between Memory Complaints and Depressive Symptoms Among Black and White Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ficker LJ, Lysack CL, Hanna M, Lichtenberg PA. Perceived cognitive impairment among African American elders: Health and functional impairments in daily life. Aging & mental health. 2014;18(4):471–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bazargan M, Barbre AR. The effects of depression, health status, and stressful life-events on self-reported memory problems among aged blacks. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1994;38(4):351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorelick PB, Harris Y, Burnett B, Bonecutter FJ. The recruitment triangle: reasons why African Americans enroll, refuse to enroll, or voluntarily withdraw from a clinical trial. An interim report from the African-American Antiplatelet Stroke Prevention Study (AAASPS). Journal of the National Medical Association. 1998;90(3):141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fritsch T, McClendon MJ, Wallendal MS, Hyde TF, Larsen JD. Prevalence and cognitive bases of subjective memory complaints in older adults: evidence from a community sample. Journal of neurodegenerative diseases. 2014;2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2006;20(4):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hachinski VC, Iliff LD, Zilhka E, et al. Cerebral blood flow in dementia. Archives of neurology. 1975;32(9):632–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer’s disease centers’ uniform data set (UDS): The neuropsychological test battery. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2009;23(2):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirk SD, Mitchell MB, Shaughnessy LW, et al. A web-based normative calculator for the uniform data set (UDS) neuropsychological test battery. Alzheimer’s research & therapy. 2011;3(6):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version. 2014;1(7):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newbold T. StatisticalModels Package. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steenland K, Goldstein FC, Levey A, Wharton W. A meta-analysis of Alzheimer’s disease incidence and prevalence comparing African-Americans and caucasians. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2016;50(1):71–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajan KB, Wilson RS, Weuve J, Barnes LL, Evans DA. Cognitive impairment 18 years before clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease dementia. Neurology. 2015:10.1212/WNL. 0000000000001774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aiken-Morgan AT, Bichsel J, Allaire JC, Savla J, Edwards CL, Whitfield KE. Personality as a source of individual differences in cognition among older African Americans. Journal of research in personality. 2012;46(5):465–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li R, Qin W, Zhang Y, Jiang T, Yu C. The neuronal correlates of digits backward are revealed by voxel-based morphometry and resting-state functional connectivity analyses. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerton BK, Brown TT, Meyer-Lindenberg A, et al. Shared and distinct neurophysiological components of the digits forward and backward tasks as revealed by functional neuroimaging. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(13):1781–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sánchez-Benavides G, Grau-Rivera O, Cacciaglia R, et al. Distinct Cognitive and Brain Morphological Features in Healthy Subjects Unaware of Informant-Reported Cognitive Decline. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2018(Preprint):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cosentino S, Brickman AM, Griffith E, et al. The right insula contributes to memory awareness in cognitively diverse older adults. Neuropsychologia. 2015;75:163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zamboni G, Drazich E, McCulloch E, et al. Neuroanatomy of impaired self-awareness in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cortex. 2013;49(3):668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy BR, Mathis CC, Woods AK. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: healthcare for diverse populations. Journal of cultural diversity. 2007;14(2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kind AJ, Buckingham WR. Making Neighborhood-Disadvantage Metrics Accessible—The Neighborhood Atlas. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(26):2456–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timpo PNP. Neighborhood Influence on Memory: Do Neighborhood Characteristics Play a Role in Memory Declines in African American Older Adults? 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Touradji P, Small SA, Stern Y. Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8(3):341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.