Abstract

The research study was conducted to utilize by-products of baby corn in the development of soup mix. Baby corn powder was obtained by drying and grinding of cut pieces of baby corn. Different formulations of soup mixes were prepared by altering the level of baby corn powder (10–40%), corn flour, salt, mango, onion, garlic, cumin, black pepper, coriander and sugar powders. Formulation 2—baby corn powder:corn flour:onion powder:garlic powder:salt:sugar:mango powder:coriander powder:cumin powder:black pepper in ratio of 20:42:2:2:10:6:15:1:1:1 was selected best on the basis of proximate, functional, pasting and sensory parameters. Soup mix was stored under ambient conditions and a declining trend was observed for antioxidant activity (67.64–48.41% DPPH inhibition), water absorption index (3.15–2.58 g/g), pH (6.81–4.15) and sensory score whereas total plate count, moisture and viscosity were found increasing after every 15 days interval. After 5 months of storage, color and sensory parameters declined. This study is valuable in promoting exploitation of by-products of baby corn by preparing soup mix that can alleviate the problem of postharvest losses and by-product utilization.

Keywords: Baby corn, Corn flour, Functional properties, Pasting properties, Soup mix

Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.) is the world’s third major cereal crop after wheat and rice. Based on endosperm of kernels, maize is classified into different groups among which baby corn is grown for vegetable purpose (Singh et al. 2017). Baby corn is the unfertilised cob of maize preferably harvested within 24 h of silk emergence depending upon the growing season. It is very appetizing, sweet and easily consumed as a natural food because of its softness and crunchiness with full of nutrients (Pandey and Gupta 2002).

Baby corn has high nutritive value, eco-friendly, attractive, very fine, sweet flavor, taste, color and crispy nature which make it unique option for different traditional and continental dishes. It has also been proved that it is a potential crop for diet diversification as it adds very special touch to many other different dishes. Harvested fresh baby corn possesses good characteristics like green, soft, delicious, nutritious, palatable and high digestibility (Singh et al. 2010).

Drying is the traditional and oldest method of processing vegetables to reduce the moisture content and enhance the shelf life. There are number of drying methods such as sun drying, hot-air oven drying and microwave drying. Hot-air drying using tray or cabinet driers are mostly used in industry for drying purpose. Drying protects the food from microbial hazards because it lowers the water activity which in turn discourages the microbial growth. Appropriate storage conditions protect the dried products from infection by insects and rodents (Kumar et al. 2015).

Soup is basically a liquid heterogeneous traditional food which is an appetizer, warm and healthy food during cold and sickness. It is served hot and prepared by using vegetables or meat with stock, juice or water with some thickening agent like starch or corn starch. Soups are classified into two main groups: clear soup and thick soups. Clear extracts of edible animal or plant parts, cereal or pulse flour and starch are the main ingredients for the preparation of clear soups and thick soups are prepared mainly from cream or eggs (Singh and Prasad 2015).

Dry soup mixes can be protected from enzymatic and oxidative spoilage and strengthen the flavor at room temperature over a long period of time (6–12 months). Soup mixes are widely preferred by consumers because they are easy to prepare. Dried soup mixes gained more popularity day by day because of it convenience, hygienic conditions, extensible shelf life and easy to carry properties. Soup mix formulated with functional ingredients resulted in improved antioxidant activity (Rekha et al. 2010). Availability of dried soup year round rather than seasonally is the best and important advantage of drying process.

In soup, corn flour acts as primary component for thickness and viscosity, an important indicator that provides final body and texture of the product (Ravindran and Matia-Merino 2009). Garlic powder has antifungal, antibacterial, cardiac-protective and antioxidant properties (Ayoka et al. 2016). Sugar and salt are natural preservatives. They efficiently decrease the growth of micro-organisms in food products (Sharma 2015). Coriander powder works as anti-diabetic agent. In India it is used for its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antibacterial properties (Rathore et al. 2013). Mango powder improves digestion, fight acidity and contain powerful antioxidants that ensure good bowel movement to prevent constipation and flatulence. In this study, baby corn soup mix was developed by formulation with functional ingredients such as corn flour, onion powder, garlic powder, black pepper, cumin, coriander powder, mango powder, salt and sugar.

Processing of baby corn is important because after harvesting, it begins to degrade quickly. Fresh baby corn is highly perishable commodity having shelf life of less than a week under ambient conditions. Field Fresh Foods Pvt. Ltd. Ladhowal, Ludhiana is in the business of packaging and export of fresh baby corn. Over size, under size as well as cut pieces of baby corn are generated as byproducts during packaging of fresh baby corn. This study was planned to utilize oversize, undersize and cut pieces of baby corn by tray drying and baby corn powder was obtained. Drying studies were part of this work and are not discussed in this paper. Baby corn powder was formulated with other ingredients for preparation of baby corn soup mix and it was further evaluated for storage studies under ambient conditions.

Materials and methods

Materials

Baby corn cut pieces were procured from Field Fresh Foods Pvt. Ltd. Ladhowal, Ludhiana. Other materials like corn starch, onion powder, garlic powder, salt, black pepper, cumin, coriander, mango powder and sugar were procured from local super market. Chemicals used for analysis were obtained from SRL Chemicals, Mumbai.

Preparation of baby corn powder and soup formulation

Baby corn cut pieces were chopped and dried at 50 °C ± 2 °C for 24 h using lab scale tray drier. Dried baby corn was ground to fine powder using lab scale grinder and sieved through 315 µm sieve.

Four different formulations (Formulation 1 to Formulation 4) were designed by varying dried Baby corn powder at 10, 20, 30, and 40% and corn flour at 52, 42, 32 and 22% whereas onion powder 2%, garlic powder 2%, salt 10%, sugar 6%, mango powder 15% coriander powder, cumin and black pepper 1% each was taken in all formulations. Levels of onion, garlic, salt, mango, coriander, cumin and black pepper were followed as described by Abdel-Haleem and Omran (2014) with modifications. Soup mix formulations were prepared by dry mixing all the ingredients, different blends were tested for soup making quality. Soup was prepared by taking soup mix to water in the ratio 1:10. Cooking was done for 5–6 min.

Analysis

Proximate composition

Moisture, ash, fat, fiber, protein and pH of soup mix were determined according to the standard methods given by AOAC (2012). Carbohydrate content was calculated by difference.

Functional and pasting properties

Water absorption indexes, oil absorption index and foam capacity were determined using the methods described by Chandra et al. (2015). Water activity of sample was measured by digital water activity meter Pawkit (Decagon devices, Inc., Pullman, Washington, USA). Bulk density was calculated by filling pre-weighed measuring cylinder (100 ml) up to the 100 ml mark with powder and weighing filled cylinder. For trapped density same process was followed but with repeatedly tapping cylinder (100 times) until no more powder can be added (Kaushal et al. 2012). Pasting properties of soup mix powder were determined by using a rapid visco analyser (RVA) starch master R&D P pack V 3.0, Newport Scientific, Warrie Wood, Australia (Iwe et al. 2016).

Color and viscosity

Color measurement of baby corn soup mix was done by Colour Flex meter using 45°/0° geometry with a standard illuminant C (Hunter Lab Colour Flex 150 Hunter Associates Inc., USA) by observing L* (0 to 100, dark to light), a* (±, green/red), and b*(±, blue/yellow) values. Viscosity of the baby corn soup mix was measured using Brookfield viscometer (Model No. LVT, USA) with spindle no 3 at 30 rpm and 45 °C temperature. All viscosity measurements were done immediately after cooking (Bahti et al. 2015)

Antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity was determined with 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazil (DPPH) to measure the scavenging activity of the free radicals (Kaur et al. 2019). Samples (1 g) were extracted for 4 h at 30 ± 1 °C with 50 ml of 80% (w/v) methanol in an orbital shaker. The obtained extract after shaking was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, from that 1.0 ml was mixed with 1.0 ml of tris buffer in a test tube. In the mixture, 2.0 ml of DPPH was added and incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature conditions. Methanol was used as control and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm.

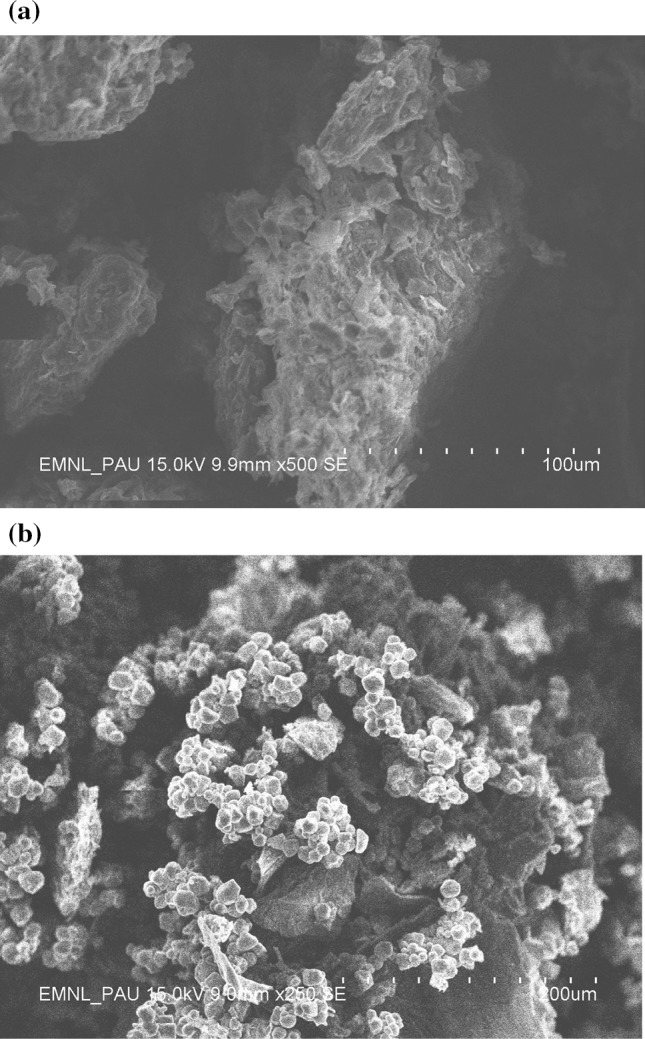

Morphological and microbiological analysis

Morphological structure of baby corn powder and soup mix was observed under scanning electron microscope (SEM). Scanning electron microscope was used to magnify the dry baby corn powder and soup mix at variable magnifications. The samples were lightly sprinkled on a double adhesive tape, which was stuck on an aluminum stub. The stubs were coated with gold up to a width of 300 Å with a sputter coater and then observed under Scanning Electron Microscope. SEM Photomicrographs of suitable magnification were obtained. Total plate count was determined by method of Swalson et al. (2001) at regular intervals during storage.

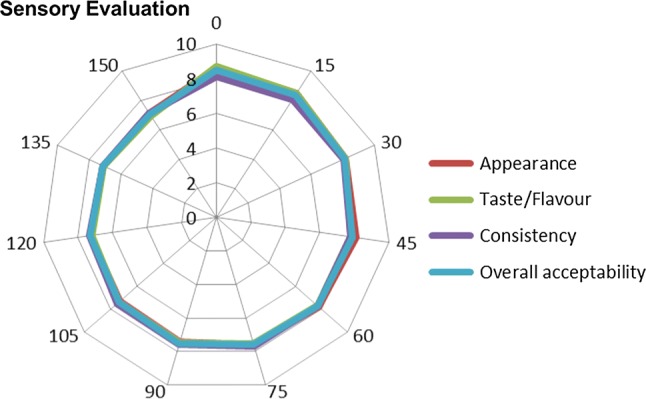

Sensory analysis

Prepared baby corn soup was evaluated by sensory evaluation panel for appearance, viscosity, taste, flavor, and overall acceptability by a panel of minimum 20 semi-trained judges (Larmond 1970).

Storage studies

Selected baby corn soup mix (Formulation 2) was packed in aluminum laminate pouches, stored for 5 months under ambient conditions and evaluated for antioxidant activity, moisture, viscosity, pH, total plate count, water absorption index and sensory parameters at 15 days interval.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using one-way Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and was expressed as mean ± standard deviation (Gomez and Gomez 2010) using SPSS software 16.0 version for windows. Significant difference between experimental samples was tested using Duncan’s multiple comparison test for comparisons (p ≤ 0.05). All the results were the average of three replicates.

Results and discussion

Physico-chemical, functional and pasting properties of baby corn powder

The physico-chemical composition (moisture, fat, fiber, ash, protein and carbohydrate content) of baby corn powder is presented in Table 1. Baby corn powder contained 9.66% moisture, 1.69% fat, 20.35% fiber, 4.91% ash, 16.34% protein and 47.05% carbohydrates. The results were comparable to the finding of Kaur et al. (2018) who reported that baby corn is good source of various nutrients and its nutritional status is at par or even superior to many other commonly used vegetables. Baby corn powder being a good source of dietary fiber (20.35%) can promote healthy bowl movement, control sugar, blood cholesterol and can assist in weight management as it will take more time to digest and give feeling of fullness (Hooda and Kawatra 2013).

Table 1.

Physico-chemical, functional and pasting properties of baby corn powder

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 9.66 ± 0.41 |

| Fat (%) | 1.69 ± 0.17 |

| Fibre (%) | 20.35 ± 0.139 |

| Ash (%) | 4.91 ± 0.147 |

| Protein (%) | 16.34 ± 0.39 |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 49.08 ± 0.55 |

| Functional properties | |

| Bulk density (kg/m3) | 396.97 ± 1.23 |

| Tap density (kg/m3) | 536.73 ± 1.24 |

| Foaming capacity (%) | 60 ± 0.082 |

| Water absorption index (g/g) | 9.951 ± 0.037 |

| Oil absorption index (g/g) | 2.953 ± 0.041 |

| Water activity | 0.423 ± 0.005 |

| Pasting properties | |

| Pasting temperature (°C) | 50.27 |

| Peak viscosity (cP) | 7006 |

| Hold viscosity (cP) | 3306 |

| Final viscosity (cP) | 6283 |

| Break down (cP) | 3707 |

| Set back (cP) | 2975 |

Values are expressed as means of three replications ± standard deviation

Formulation I—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 10:52

Formulation II—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 20:42

Formulation III—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 30:32

Formulation IV—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 40:22

Each formulation contains onion:garlic:salt:sugar:mango:coriander:cumin:black pepper powders in ratio of 2:2:10:6:15:1:1:1

The functional properties of baby corn powder are summarized in Table 1 The bulk and tap density were 396.97 kg/m3 and 536.73 kg/m3 respectively. Bulk density depends on both the density of powder particles and on the arrangement of the powder particles. The interparticle interactions that affect the bulk properties of a powder are also the interactions that interfere with powder flow. Comparing the bulk and tapped densities can be used as index to check ability of powder to flow (Kaushal et al. 2012). Foam capacity of flours refers to the amount of interfacial area that can be created by proteins present in flour. Foam is a colloid of many gas bubbles trapped in a solid or liquid (Chandra et al. 2015). The foaming capacity of baby corn powder was observed very high i.e. 60%. Water and oil absorption index were 9.951 g/g and 2.953 g/g respectively. High water absorption index suggests that baby corn powder can be useful in products where good viscosity is required such as soup and gravies. Water activity is a measure of microbial susceptibility because fungi cannot grow in flour below 0.7 water activity (Jay 1992). Baby corn powder had water activity 0.423 which indicated that the powder is shelf stable at room temperature.

Pasting properties is the study of changes that occur after starch gelatinization with further heating which includes swelling of granules, leaching of components from granules and eventual breaking of granules with application of shear forces. Pasting parameters are studied by observing changes that occur in viscosity of a starch system and it is based on rheological principles (Tester and Morrison 1990). Pasting properties of baby corn powder are mentioned in Table 1. The pasting temperature was measured to be 50.27 °C. It is the minimum temperature taken by flour for cooking. Peak viscosity is the highest viscosity achieved by gelatinized starch during heating with water and it was observed 7006 cP for baby corn powder. Holding strength evaluate the ability of starch to remain undisturbed when paste is passed through a long period of high, constant temperature during steaming and it was 3306 cP. Set back viscosity is the measure of re-crystallization of gelatinized starch during cooling and set back viscosity of baby corn powder was 2975 cP. Final viscosity of baby corn powder was 6283 cP that indicated the ability of this powder to form a viscous paste after cooking and cooling and high resistance of the paste to shear force during stirring (Iwe et al. 2016). The increase in viscosity during cooling indicates not only the normal inverse relation between temperature and viscosity of the sample suspension but it also shows the tendency of various constituents present in hot paste to retrograde as the temperature decreases.

Effect of different formulations on proximate composition and color of baby corn soup mix

The effect of different formulations on proximate composition and color of baby corn soup mix is presented in Table 2. It was observed that increasing the level of baby corn powder in formulations decreased the moisture content from 9.33 to 7.73%. This variation in moisture content was observed due to decrease in level of corn flour that lowered the moisture content of soup mixes from formulation 1 to formulation 4. El Wakeel (2007) reported that keeping the moisture content of dried food materials less than 10% prevents the growth of microorganisms and considered fit for shelf stability of soup ingredients. Carbohydrates content of the formulations varied between 64.69 and 69.54%. There was a non- significant effect on fat content, whereas ash, protein and fiber content increased with increase in level of baby corn powder in formulations. This data proved that increase in level of baby corn powder in soup mix result in increase in protein and ash content and the trend was similar to the findings of Gandhi (2017).

Table 2.

The effect of different formulations on proximate composition and color of baby corn soup mix

| Parameters | Formulation 1 | Formulation 2 | Formulation 3 | Formulation 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 9.33a ± 0.16 | 9.06a ± 0.12 | 8.06b ± 0.12 | 7.73b ± 0.32 |

| Ash (%) | 11.2b ± 0.24 | 11.8b ± 0.24 | 11.86ab ± 0.36 | 12.53a ± 0.28 |

| Fat (%) | 1.03a ± 0.032 | 1.120b ± 0.016 | 1.286c ± 0.020 | 1.446d ± 0.036 |

| Protein (%) | 6.33d ± 0.02 | 7.14c ± 0.03 | 7.92b ± 0.04 | 8.73a ± 0.03 |

| Fibre (%) | 4.03a ± 0.03 | 5.420b ± 0.01 | 6.28c ± 0.02 | 7.06d ± 0.04 |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 69.54a ± 0.02 | 67.93b ± 0.09 | 66.82b ± 0.04 | 64.69c ± 0.103 |

| Colour | ||||

| L* | 46.24a ± 0.04 | 46.07b ± 0.03 | 45.74c ± 0.02 | 44.14d ± 0.02 |

| a* | 0.42a ± 0.0 | 0.42a ± 0.0 | 0.42a ± 0.0 | 0.42a ± 0.0 |

| b* | 5.65d ± 0.02 | 6.24c ± 0.02 | 6.74b ± 0.02 | 7.54a ± 0.02 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation

Values with different superscripts in a column differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Formulation I—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 10:52

Formulation II—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 20:42

Formulation III—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 30:32

Formulation IV—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 40:22

Each formulation contains onion:garlic:salt:sugar:mango:coriander:cumin:black pepper powders in ratio of 2:2:10:6:15:1:1:1

Color is an important quality parameter of soup mixes, color measurements of various formulations of soup mixes are illustrated in Table 2. Data indicated that L* and b* values of the sample varied significantly whereas a* value, that represent redness was observed same for all samples. The b* values which represent yellowness, increased with increase in the level of baby corn powder due to yellow color of baby corn, while the L* values which represent lightness decreased on increase in baby corn powder which is similar to the findings of Pathare et al. (2013) who studied the color measurement in fresh and processed foods.

Effect of different formulations on functional, pasting and sensory properties of baby corn soup mix

The effect of different formulations on functional, pasting and sensory properties of baby corn soup mix is summarized in Table 3. Water absorption index measures the volume occupied by granule or starch polymer after swelling in excess of water (Chandra et al. 2015). It was observed that on increasing the level of baby corn powder the water absorption index, oil absorption index, foaming capacity, bulk density and tap density increased significantly. Bulk density is the ratio of mass to the apparent volume of specific container; it is an important character that affects the required storage space at processing plant or for shipping (Gandhi 2017). Data stated that increase in baby corn powder increased the bulk density and tapped density of formulations. Increase in foaming capacity of formulations was observed due to high foaming capacity of baby corn powder (60%). Water activity of the soup mix varied non significantly. Water activity is the measure of water availability for the growth of microorganisms and it is a major issue in chemical stability of dry mixes and considered as an intrinsic factor in determining shelf life (Bonazzi and Dumoulin 2011). Antioxidants are compounds that inhibit oxidation and oxidation is a chemical reaction that produces free radicals, thereby leading to chain reactions that may damage the cells of organisms. The antioxidant activity of baby corn soup mix increased with increasing the level of baby corn powder (65.04–70.01% DPPH inhibition). Results are in concordance with previous study by Martínez-Tomé et al. (2015).

Table 3.

The effect of different formulations on functional, pasting and sensory characteristics of baby corn soup mix

| Formulation 1 | Formulation 2 | Formulation 3 | Formulation 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional properties | ||||

| Water absorption index g/g | 2.461d ± 0.041 | 3.153c ± 0.04 | 3.802b ± 0.053 | 4.273a ± 0.035 |

| Oil absorption index g/g | 2.334c ± 0.043 | 2.468b ± 0.035 | 2.583a ± 0.014 | 2.601a ± 0.025 |

| Water activity | 0.413a ± 0.004 | 0.412a ± 0.004 | 0.420a ± 0.004 | 0.410a ± 0.004 |

| Foaming capacity (%) | 2.13d ± 0.12 | 6.2c ± 0.08 | 10.2b ± 0.08 | 16.53a ± 0.28 |

| Bulk density (Kg/m3) | 488.10d ± 1.12 | 551.40c ± 1.59 | 562.85b ± 1.07 | 567.74a ± 2.15 |

| Tap density (Kg/m3) | 715.96c ± 1.34 | 725.81c ± 1.83 | 728.62ab ± 1.09 | 730.97a ± 1.39 |

| Antioxidant activity (% DPPH inhibition) | 65.04d ± 0.29 | 67.76c ± 0.31 | 69.91b ± 0.24 | 70.01a ± 0.21 |

| Pasting properties | ||||

| Pasting temperature (°C) | 89.2d | 90.2c | 90.6b | 91.2a |

| Peak viscosity (cP) | 855a | 724b | 573c | 375d |

| Hold viscosity (cP) | 624a | 518b | 387c | 233d |

| Final viscosity (cP) | 847a | 754b | 633c | 454d |

| Break down (cP) | 234a | 203b | 184c | 145d |

| Set back viscosity (cP) | 224c | 244b | 246a | 247a |

| Sensory parameters | ||||

| Appearance | 7.02c ± 0.41 | 8.12a ± 0.37 | 7.3b ± 0.36 | 6.86d ± 0.26 |

| Consistency | 7.17b ± 0.31 | 8.05a ± 0.19 | 7.2b ± 0.28 | 6.37c ± 0.37 |

| Taste/flavour | 7.2b ± 0.34 | 8.35a ± 0.33 | 7.1b ± 0.42 | 6.75c ± 0.31 |

| Overall acceptability | 7.13b ± 0.25 | 8.17a ± 0.17 | 7.2b ± 0.24 | 6.66c ± 0.24 |

Values with different superscripts in a column differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Formulation I—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 10:52

Formulation II—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 20:42

Formulation III—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 30:32

Formulation IV—Baby corm powder:corn starch in ratio of 40:22

Each formulation contains onion:garlic:salt:sugar:mango:coriander:cumin:black pepper powders in ratio of 2:2:10:6:15:1:1:1

Pasting properties of formulations determined by Rapid Visco Analyzer (RVA) are presented in Table 3. Significant differences in the pasting temperature, peak viscosity, hold viscosity, final viscosity, breakdown viscosity and set back viscosity were observed among formulations tested for their behaviors during heating and cooling cycles. Peak viscosity ranged between 375 (Formulation 1) to 855 cP (Formulation 4), results revealed a negative correlation between peak viscosity and protein content of formulations. Similar trend was observed for hold viscosity, final viscosity and break down viscosity. Low protein and high carbohydrate content of Formulation 1 resulted in high swelling ability, these viscosity parameters correlates well with the quality of final product that provides an indication of viscous load likely to be encountered during preparation of soup (Kaur et al. 2011). The pasting temperature and set back viscosity increased on increasing the level of baby corn powder. Overall, a negative correlation of viscosity attributes with the protein and positive with carbohydrate content was observed. The results are in accordance to the finding of Kaushal et al. (2012) who studied the pasting properties of different flours and there blends.

Sensory analysis is a valuable tool in the problems associated with food acceptability. It is useful tool in product development, product improvement and quality maintenance (Singh-Ackbarali and Maharaj 2014). Dry soup mix must have desired sensory attributes, representing dominant aroma and flavor of the ingredients added. Sensory quality parameters of resultant formulations of soup mix are presented in Table 3. Data revealed that all formulation significantly (p ≤ 0.05) affects appearance, consistency, taste/flavor and overall acceptability of resultant soup. Baby corn incorporation at 20% level showed highest score for all sensory attributes by sensory panelists. Thus Formulation 2 (baby corn powder:corn flour:onion powder:garlic powder:salt:sugar:mango powder:coriander powder:cumin powder:black pepper in ratio of 20:42:2:2:10:6:15:1:1:1) was selected best among all formulations and followed for further storage studies.

Morphological structure of powder and soup mix

The cellular structures of baby corn powder and baby corn soup mix (Formulation 2) were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). SEM has a very essential role in understanding granular structures of powders and soup mixes. Baby corn powder particles were intact very closely with each other, no particular shape was observed (Fig. 1a) whereas, baby corn soup mix that was having other ingredients showed a significant variation in size and shape of granules. Figure 1b represents the morphological structures of soup mix that appeared hexagonal and round shape. Size and shape of soup mix have been found to be affected upon forming agglomeration and indicated in the narrow size distribution in particle size analysis, that was found to be in accordance with earlier studies for high amylose rice starch and instant vegetable soup mix prepared by extrusion technology, respectively (Zhang et al. 2014; Gandhi 2017).

Fig. 1.

Morphological structure: a baby corn powder; b baby corn soup mix

Effect of storage on baby corn soup mix

Selected formulation was packed in aluminum laminate pouches, stored under ambient conditions and was evaluated for change in antioxidant activity, moisture, viscosity, pH, water absorption index and total plate count after every 15 days intervals (Table 4). Moisture content of the product is the important parameter defining the stability of products during storage. It was observed that the moisture content varied non-significantly during storage period and variation was 9.47–9.57%. Increase in moisture content during storage may be due to absorption of moisture from atmosphere through diffusion of vapors from microscopic pores of packaging materials (Sharma et al. 2013). DPPH assay evaluates the ability of antioxidants to quench the stable DPPH radical. Antioxidants convert DPPH to 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl hydrazine (Rekha et al. 2010). Antioxidant activity decreased significantly from 67.64 to 48.41% during storage of soup mix. Our results agreed with those obtained by Martínez-Tomé et al. (2015) who reported decreasing antioxidant activity of four dehydrated soups during storage of 12 months.

Table 4.

Effect of storage on various quality parameters

| Storage period | Antioxidant (% DPPH inhibition) | Moisture (%) | Viscosity (cP) | pH | TPC count (× 102log cfu/g) | Water absorption index (g/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 67.64a ± 0.00 | 9.47g ± 0.012 | 266.67g ± 18.85 | 6.81a ± 0.013 | 2.70j ± 0.12 | 3.150a ± 0.002 |

| 15 | 67.34a ± 0.09 | 9.51f ± 0.008 | 266.67g ± 37.71 | 6.75b ± 0.013 | 2.92j ± 0.13 | 3.093b ± 0.003 |

| 30 | 66.47b ± 0.15 | 9.52ef ± 0.004 | 293.37g ± 18.85 | 6.54c ± 0.013 | 3.23i ± 0.020 | 3.002c ± 0.002 |

| 45 | 65.49c ± 0.17 | 9.53de ± 0.004 | 346.67f ± 18.85 | 6.26d ± 0.022 | 3.38h ± 0.015 | 2.942d ± 0.001 |

| 60 | 63.65d ± 0.09 | 9.53de ± 0.004 | 360f ± 32.65 | 6.02e ± 0.13 | 3.46g ± 0.020 | 2.872e ± 0.003 |

| 75 | 62.43e ± 0.24 | 9.54cd ± 0.004 | 373.37ef ± 18.85 | 5.83f ± 0.028 | 3.55f ± 0.321 | 2.813f ± 0.003 |

| 90 | 60.56f ± 0.13 | 9.55bc ± 0.004 | 413.37de ± 18.85 | 5.53g ± 0.024 | 3.62e ± 0.045 | 2.784g ± 0.003 |

| 105 | 58.56g ± 0.12 | 9.56ab ± 0.004 | 453.37cd ± 18.85 | 5.23h ± 0.022 | 3.71d ± 0.040 | 2.715h ± 0.002 |

| 120 | 55.63h ± 0.16 | 9.57a ± 0.004 | 493.37bc ± 18.85 | 4.93i ± 0.136 | 3.75c ± 0.020 | 2.683i ± 0.003 |

| 135 | 53.43i ± 0.20 | 9.57a ± 0.004 | 533.37ab ± 18.85 | 4.43j ± 0.026 | 3.80b ± 0.035 | 2.622j ± 0.002 |

| 150 | 48.41j ± 0.09 | 9.57a ± 0.009 | 560a ± 32.65 | 4.15k ± 0.314 | 3.84a ± 0.053 | 2.582k ± 0.002 |

Values with different superscripts in a column differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Viscosity of baby corn soup mix increased significantly from 266.67 to 560 cP during storage. Nwosu et al. (2011) reported increase in viscosity with storage of soup thickener Brachystegia enrycoma (Achi). pH of baby corn soup prepared from soup mix decreased significantly (6.81–4.15) during storage. A decline in pH of soup was earlier reported by Moreira et al. (2015), this reduction can possibly due to high microbial load during storage. Total plate count of baby corn soup mix was analyzed regularly during storage and it was observed increasing significantly with days of storage. Jay (1992) reported that a product is microbiologically safe if total microbial count of dry soup is less than 1 × 104 cfu/g. The results were in accordance with the findings of a study on microflora of steeped and cured baby corn (Kaur et al. 2009). Water absorption index measures the volume occupied by the granule or starch polymer after swelling in excess of water. The water absorption index decreased significantly from 3.150 to 2.582 g/g, the results were comparable to finding of Nwosu et al. (2011). Water absorption index declined with rise of moisture content, which might be due to reduction of elasticity of mix through plasticization of melt at increased moistures (Kaur et al. 2009).

The effect of storage on the sensory characteristics i.e. appearance, taste/flavor, consistency and overall acceptability of baby corn soup mix stored at ambient temperature are presented in Fig. 2. It was observed that the appearance, taste/flavor and consistency scores significantly decreased with the storage which led to a decrease in the overall acceptability of the soup mix, the trends were similar to the findings of Gandhi (2017). The results of storage showed that soup mix was organoleptically acceptable up to 5 months of storage period. There was slight browning of color of soup mix which is due to oxidation of functional compounds, but there was least variation in flavor of soup prepared from mix. From the results it could be deduced that the baby corn powder prepared from industrial by-products be utilized at 20% level of incorporation for preparation of nutritious soup mix having shelf life of 5 months.

Fig. 2.

Effect of storage on sensory scores of baby corn soup mix

Conclusion

Baby corn powder obtained by drying of industrial by-products can be successfully used at 20% level of incorporation for preparation of soup mix. On the basis of functional, pasting and sensory parameters of soup, formulation 2 i.e. baby corn powder:corn flour:onion powder:garlic powder:salt:sugar:mango powder:coriander powder:cumin powder:black pepper in ratio of 20:42:2:2:10:6:15:1:1:1 was selected. This formulation had 7.14% protein, 5.4% fibre and 11.8% ash content that could improve the nutrition of consumers. Storage of soup mix showed minor changes towards sensory attributes, increase in viscosity, decline in antioxidant activity and pH but the product remained acceptable till the stored period of 5 months. Hence the by-products of baby corn processing industry could be effectively utilized in the production of baby corn soup mix.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Head, Department of Food Science and Technology, Punjab Agricultural University for providing necessary laboratory facilities. Authors are also thankful to Mr. Aman Thapar, Plant Head, Field Fresh Foods Pvt. Ltd. Ladhowal for providing raw material to conduct the studies.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdel-Haleem AM, Omran AA. Preparation of dried vegetarian soup supplemented with some legumes. Food Nutr Sci. 2014;5:2274–2285. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis. 17. Washington: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoka AO, Ademoye AK, Imafidon CE, Ojo EO, Oladele AA. Aqueous extract of Allium sativum (Linn.) bulbs ameliorated pituitary-testicular injury and dysfunction in Wistar rats with Pb-induced reproductive disturbances. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2016;4(2):200. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2016.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahti AM, Musameh SM, Abdelraziq IR. Rheological properties (acidity) for olive oil in Palestine. Mater Sci. 2015;12:185–225. [Google Scholar]

- Bonazzi C, Dumoulin E. Quality changes in food materials as influenced by drying processes. In: Tsotsas E, Mujumdar AS, editors. Product quality and formulation. New York: Wiley; 2011. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Singh S, Kumari D. Evaluation of functional properties of composite flours and sensorial attributes of composite flour biscuits. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52:3681–3688. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1427-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Wakeel MA (2007) Ultra structure and functional properties of some dry mixes of food. M.Sc. Thesis, Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University, Cairo

- Gandhi N (2017) Development of instant vegetable soup mixes using extrusion technology. Ph.D. Thesis, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, India

- Gomez AK, Gomez AA. Statistical procedures for agricultural research. New York: Wiley; 2010. p. 680. [Google Scholar]

- Hooda S, Kawatra A. Nutritional evaluation of baby corn (zea mays) Nutr Food Sci. 2013;43:68–73. doi: 10.1108/00346651311295932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwe M, Onyeukwu U, Agiriga A. Proximate, functional and pasting properties of FARO 44 rice, African yam bean and brown cowpea seeds composite flour. Cogent Food Agric. 2016;2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jay JM (1992) Incidence and types of microorganisms in foods. In: Modern food microbiology. Springer, Berlin, pp 63–93

- Kaur R, Aggarwal P, Sahota P, Kaur A. Changes in microflora of steeped and cured baby corn (Zea mays L.) J Hortic For. 2009;1:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M, Kaushal P, Sandhu KS. Studies on physicochemical and pasting properties of Taro (Colocasia esculenta L.) flour in comparison with a cereal, tuber and legume flour. J Food Sci Technol. 2011;50:94–100. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0227-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur N, Kaur K, Aggarwal P. Parameter optimization and nutritional evaluation of naturally fermented baby corn pickle. Agric Res J. 2018;55:548–553. doi: 10.5958/2395-146X.2018.00096.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R, Kaur K, Ahluwalia P. Effect of drying temperatures and storage on chemical and bioactive attributes of dried tomato and sweet pepper. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal P, Kumar V, Sharma HK. Comparative study of physicochemical, functional, antinutritional and pasting properties of taro (Colocasia esculenta), rice (Oryza sativa) flour, pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) flour and their blends. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2012;48:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.02.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Bohra JS, Kumawa N, Singh AK. Fodder yield, nutrient uptake and quality of baby corn (Zea mays L.) as influenced by NPKS and Zn fertilization. Res Crops. 2015;16:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Larmond E (1970) Methods of sensory evaluation of food. Canada Department of Agriculture, Publication No. 1637

- Martínez-Tomé M, Murcia MA, Mariscal M, Lorenzo ML, Gómez-Murcia V, Bibiloni M, Jiménez-Monreal AM. Evaluation of antioxidant activity and nutritional composition of flavoured dehydrated soups packaged in different formats. Reducing the sodium content. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52:7850–7860. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-1940-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira SA, Fernandes PA, Duarte R, Santos DI, Fidalgo LG, Santos MD, Queirós RP, Delgadillo I, Saraiva JA. A first study comparing preservation of a ready-to-eat soup under pressure (hyperbaric storage) at 25 °C and 30 °C with refrigeration. Food Sci Nutr. 2015;3:467–474. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu JN, Ogueke CC, Owuamanam CI, Onuegbu N. The effect of storage conditions on the proximate and rheological properties of soup thickener Brachystegia enrycoma (Achi) Rep Opin. 2011;3:52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey AK, Gupta VHS. Effect of integrated weed management practices on yield and economics of baby corn (Zea mays L.) Indian J Agric Sci. 2002;72:206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Pathare PB, Opara UL, Al-Said FAJ. Colour measurement and analysis in fresh and processed foods: a review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013;6:36–60. doi: 10.1007/s11947-012-0867-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore SS, Saxena SN, Singh B. Potential health benefits of major seed spices. Int J Seed Spices. 2013;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran G, Matia-Merino L. Starch–fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) polysaccharide interactions in pure and soup systems. Food Hydrocoll. 2009;23:1047–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2008.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rekha MN, Yadav AR, Dharmesh S, Chauhan AS, Ramteke RS. Evaluation of antioxidant properties of dry soup mix extracts containing dill (Anethum sowa L.) leaf. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2010;3:441–449. doi: 10.1007/s11947-008-0123-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S. Food preservatives and their harmful effects. Int J Sci Res Publ. 2015;5:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SK, Chaudhary SP, Rao VK, Yadav VK, Bisht TS. Standardization of technology for preparation and storage of wild apricot fruit bar. J Food Sci Technol. 2013;50:784–790. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0396-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Y, Prasad K. Sorption isotherms modeling approach of rice-based instant soup mix stored under controlled temperature and humidity. Cogent Food Agric. 2015;1:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Singh MK, Singh RN, Singh SP, Yadav MK, Singh VK. Integrated nutrient management for higher yield, quality and profitability of baby corn (Zea mays L.) Indian J Agron. 2010;55:100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Singh G, Walia SS, Kumar B. Agronomic and genetic approaches to improve nutrient use efficiency and its availability in baby corn (Zea mays L.)—a review. Front Crop Improv. 2017;5:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Ackbarali D, Maharaj R. Sensory evaluation as a tool in determining acceptability of innovative products developed by undergraduate students in food science and technology at the University of Trinidad and Tobago. J Curric Teach. 2014;3:10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Swalson KMJ, Petran RL, Hanlin JH. Culture methods for enumeration of microorganisms. In: Downes FR, Ito K, editors. Compendium of methods for microbial examination of foods. 4. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tester RF, Morrison WR. Swelling and gelatinization of cereal starches. I. Effects of amylopectin, amylose, and lipids. Cereal Chem. 1990;67:551–557. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu W, Liu C, Luo S. Retrogradation behaviour of high-amylose rice starch prepared by improved extrusion cooking technology. Food Chem. 2014;158:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]