Abstract

The increasing sensitivity to gluten has aroused interest in gluten-free products like bread. However, one of the biggest challenges of producing gluten-free bread is to get a good quality structure. We hypothesize that using chitosan along with transglutaminase, a network of crosslinks would be generated, guaranteeing a better structure. Thus, in the present work, we produced gluten-free bread using red rice flour and cassava flour, transglutaminase, and chitosan at concentrations of 0%, 1%, and 2%. Loaves of bread were characterized, and the instrumental texture properties during five days were determined. Bread produced with chitosan and transglutaminase presented lighter brown coloration due to incomplete Maillard reaction and low specific volumes varying from 1.64 to 1.48 cm3/g, possibly due to chitosan interfering with yeast fermentation. Rheological tests revealed increases in viscosity before and after fermentation when chitosan was used. Bread with chitosan presented high initial firmness but a lower rate of staling, possibly due to water retention. According to results, a possible network involving chitosan and other proteins promoted by transglutaminase was formed and after optimization could yield better gluten-free bread.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13197-019-04223-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Gluten-free bread, Transglutaminase, Chitosan, Instrumental texture

Introduction

Bread is one of the most consumed foods worldwide, especially those made from wheat flour (Carcea et al. 2018). However, due to growing gluten intolerance, gluten allergy, and Celiac disease, the demand for products without this protein has challenged researchers to find alternatives in other flours (Martins et al. 2019).

Bread main component is starch, which can be found in several flours from ingredients such as rice, cassava, corn, potato, and even other food byproducts without the presence of gluten (Ferreira et al. 2019). Pigmented rice varieties (Oryza sativa) have a high concentration of starch, proteins, minerals, and B vitamins and include important health-promoting phytochemicals such as anthocyanins, pro-anthocyanidins, and carotenoids, thus giving high nutritional quality (Almeida et al. 2019).

Even though high amounts of starch are present on red rice, the available proteins do not have the viscoelastic and the structuring properties of gluten. Thus, high-quality gluten-free bread still represents a challenge (Roman et al. 2019). An alternative to improve the properties of gluten-free could be the use of microbial transglutaminase, a low-cost enzyme with several applications in the food industry (Gharibzahedi et al. 2018). The microbial transglutaminase catalyzes the acyl transfer reactions causing the formation of covalent bonds between the protein fractions (Gharibzahedi et al. 2019). On wheat bread, a reaction between the amine groups leads to an improvement in the viscoelastic properties of gluten (Boukid et al. 2018). These bonds cause the dough to have higher gas retention capacity during fermentation. However, due to the absence of gluten in the bread formulation, the presence of chitosan, a polysaccharide with amine groups, could be beneficial to establish a similar network (Moore et al. 2006).

Chitosan is a polysaccharide constituted by repeated units of glucosamine (Lima et al. 2018). Some works report the addition of chitosan into bread formulation (Lafarga et al. 2013). The inclusion of chitosan and chitosan oligosaccharides has inhibitory effects on the growth of microorganisms and consequently increased shelf life (Rakkhumkaew and Pengsuk 2018). The results of the chitosan addition on the rheological attributes of bread dough were recently investigated (Ghoshal and Mehta 2019). An interlocked supramolecular assembly was formed between gluten and chitosan to reduce the celiac-toxicity of wheat flour (Ribeiro et al. 2019). Chitosan was used together with the transglutaminase to form covalent bonds between polysaccharides and proteins to create gels for medical devices (Cai et al. 2018). Therefore, chitosan presents a good alternative in the inclusion of fibers in bakery products, as well as other cereals (Mert 2019). Improvement of gluten-free bread was achieved using hydroxypropylmethylcellulose (Morreale et al. 2018). However, chitosan has yet to be tested along transglutaminase for bread production.

Finally, the present work intention was to elaborate a gluten-free bread with red rice flour with the addition of chitosan and transglutaminase enzyme. Therefore our work aimed to understand the role of the chitosan and transglutaminase on the final properties of the bread and if the bread structure presented similar quality to commercial products.

Materials and methods

Materials

Red rice was obtained in the local market of Campina Grande—PB, with an initial water content of approximately 11% (dry basis). The red rice was dried milled in 50 g batches, using a grain mill. After grinding, the red rice flours were packed in hermetically sealed polyethylene packaging, maintained at a temperature of 25 ± 3.0 °C. The chitosan powder with medium molecular weight (approximately 200 000 g/mol) and 80% deacetylation degree was obtained from CERTBIO, Campina Grande, Brazil. Transglutaminase was acquired from Ajinomoto, Ltd.

Formulation and production of bread

The formulations were developed so that the sum of the flours should be equivalent to 100%, and the other ingredients were calculated based on the amount of flour. A method where ingredients are added at once and then mixed together was used for the elaboration of the dough (Coelho and de las Mercedes Salas-Mellado 2015). Thus, the red rice flour (50%) and the cassava flour (50%) were mixed first, and then the other dry ingredients, sugar (45%), NaCl (1.15%), improver (1.15%). Chitosan was added including the chitosan (0%, 1% or 2%) and transglutaminase enzyme (0.5%). Using an industrial mixer, the final ingredients were added, rapeseed oil (7.5%), and water (45%). The amount of chitosan added to the formulations ranged from 0% (control), 1% and 2%, based on the amount of the flour. Subsequently, the dough was distributed in rectangular aluminum molds to bread (17 cm × 7 cm × 6 cm) and fermented for 30 min in a controlled fermentation chamber at 40 °C and relative humidity of 80–82%. The baking of the bread was carried out for 30 min at 200 °C. After cooling at room temperature, they were packed in polyethylene plastics. All loaves of bread were prepared in triplicate.

Rheological measurements of bread dough

Viscosity and torque measurements were performed using a Brookfield viscometer (DV-II + PRO model, Brookfield Engineering Laboratories Inc., MA, USA) at temperatures room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) using spindle speeds (50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 120, 135, 140, 150, 160, 180 and 200 rpm) according to the methodology proposed by (Lima et al. 2018). All data was taken after 30 s at each speed, with a rest in time between the measurements. Spindle RV7 was used on all experiments with torque values ranging between 25% and 80%. A 500 ml beaker was used for all measurements with the guard leg on and enough dough to cover the immersion grooves on the spindle shaft. All experiments were replicated and performed right before mixing and after the 30 min fermentation. Torque and spindle velocity were converted into shear rates and shear stress using the method proposed by (Mitschka 1982). Results were modeled using the Bingham Model (Eq. 1) and the Ostwald-Waele model (Eq. 2).

| 1 |

| 2 |

Characterization of bread

Weight loss and Oven-spring

The amount of dough used was weighed and compared to the final mass of the bread after baking. The oven-spring was determined by the difference in dough height at the end of the fermentation and the height of the baked bread. The bread format analysis was performed according to height and bread measurements in the central portion of the baked bread. The analyses were performed with the aid of a digital caliper.

Color

For crust and crumbs color measurements, the Hunter Lab Miniscan XE Plus colorimeter (Model 45/0-5, Reston, USA) was used. The values of L*, a*, and b* were determined. a* is a coordinate (− 120 to 120) representing the scale of green to red, with negative values for greenness and positive values for redness. Similarly, b* values represent negative values for blueness and positive values for yellowness, and finally, L values present the lightness of the samples and are ranged from darkness to lightness (0 to 100). Color differences between the control wheat bread and the rest of the samples were calculated using the CIE76 equation

| 3 |

The browning index, which represents the development of the brown color due to enzymatic or non-enzymatic reactions, was determined using Eqs. 4 and 5.

| 4 |

where x is

| 5 |

Water content, pH and titratable acidity

Water content was determined by the gravimetric method (AOAC method 934.06) using 3 g of the crushed bread and placed on an oven at 105 °C for 24 h (A.O.A.C 2016) For determination of pH and acidity (AOAC method 22.058), 10 g of each sample was homogenized with 90 mL of distilled water, and the pH of the suspension was determined using potentiometer model 0400 (Quimis, São Paulo, Brazil). The suspension was then titrated with 0.1 N NaOH solution until pH 8.5 was reached. The titratable acidity was expressed in mL of 0.1 N NaOH consumed per 10 g of bread. All trials were performed in triplicate.

Specific volume

The specific volume was determined in triplicate by the seed method, using millet seeds and calculated according to Eq. 6 and the results expressed in cm3 g−1

| 6 |

where Vesp is the specific volume (cm3 g−1); V is the volume of bread (cm3); m is the bread weight (g).

Textural analysis

Instrumental texture measurements were performed using a penetrometer (TA-TX plus, Stable Micro Systems, UK) equipped with a 50 N load cell. An A/BE-d35 probe was compressed twice against each bread sample of 25 mm to a defined depth (50%) at a rate of 1.7 mm/s. Measurements were performed in triplicate throughout the five days of storage. As a result of these experiments, force–time curves were built and analyzed to determine some mechanical parameters (Firmness, Cohesiveness, Chewiness) considering the following: Firmness is the force required to attain a given deformation and is given by the altitude of the first peak. Cohesiveness is the ratio between the area under both the force–time curve produced in the first and second compression. Springiness is related to elastic recovery between the first compression and the second compression. The chewiness is given by the product of the firmness x cohesiveness x springiness.

Statistical analysis

The experiment was set up in a completely randomized design (DIC), and the results were submitted to analysis of variance, Tukey test at the 5% probability level, using the software Assistat, version 7.7. Empirical models were established for the experimental texture data, and results modeled using non-linear regression into a first-order polynomial Eq. (7).

| 7 |

where y is the dependent variable, βi is the regression coefficients, T is the time (days), CC is the chitosan concentration.

Results and Discussion

Physicochemical properties of gluten-free bread

In the present work, the production of the gluten-free bread with the addition of chitosan and enzyme transglutaminase was studied. Table 1 presents the results of the physical and physicochemical characterization of the bread produced.

Table 1.

Physical and physicochemical characteristics of the gluten-free bread before and after oven baking

| Parameters | Samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (wheat bread) | 0% | 1% | 2% | ||

| Weight (g) | Before baking | 637.3 ± 1.6 | 636 ± 4.2 | 631 ± 1.4 | 639 ± 1.4 |

| After baking 200 °C. 30 min | 595.15 ± 3.0 | 598 ± 4.2 | 596 ± 2.8 | 594 ± 0.1 | |

| Height (cm) | Before Baking | 7.30 ± 0.03 | 4.50 ± 0.06 | 4.50 ± 0.05 | 4.50 ± 0.08 |

| After baking 200 °C. 30 min | 10.71 ± 0.01 | 4.55 ± 0.02 | 4.55 ± 0.03 | 4.70 ± 0.07 | |

| Water content (%) | – | 31.80 ± 0.86 | 26.46 ± 0.53a | 27.25 ± 0.55a | 27.16 ± 0.58a |

| Specific volume (cm3 g−1) | – | 2.45 ± 0.07 | 1.64 ± 0.10a | 1.48 ± 0.09b | 1.48 ± 0.05b |

| Ash (%) | – | 1.08 ± 0.01 | 1.11 ± 0.07b | 1.14 ± 0.08ab | 1.34 ± 0.10a |

| pH | – | 6.20 ± 0.06 | 5.75 ± 0.03c | 5.97 ± 0.03b | 5.97 ± 0.03b |

| Tritatable acidity | – | 3.58 ± 0.25 | 2.63 ± 0.62a | 1.99 ± 0.06b | 1.75 ± 0.06c |

| L* | Crumbs | 74.29 ± 0.38 | 56.99c ± 0.42 | 62.54a ± 0.04 | 60.85 b ± 0.22 |

| Crust | 45.19 ± 0.19 | 53.51c ± 0.12 | 59.78a ± 0.31 | 55.11b ± 0.24 | |

| + a* | Crumbs | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 7.23a ± 0.20 | 6.15c ± 0.07 | 6.76b ± 0.09 |

| Crust | 11.85 ± 0.14 | 11.28a ± 0.02 | 7.64c ± 0.16 | 8.41b ± 0.06 | |

| + bª | Crumbs | 20.64 ± 0.32 | 17.83ab ± 0.69 | 16.96b ± 0.08 | 18.77a ± 0.24 |

| Crust | 25.43 ± 0.02 | 25.24a ± 0.08 | 21.41b ± 0.48 | 21.69b ± 0.33 | |

| BI | Crumbs | 36.39 | 45.71 | 37.89 | 43.93 |

| Crust | 160.43 | 275.21 | 165.94 | 206.62 | |

| Delta E | Crumbs | Reference | 22.69 | 19.34 | 20.52 |

| Crust | Reference | 62.12 | 42.51 | 34.21 | |

Considering the mass loss, it was observed that there was a loss of 7.04% in the weight for the bread with 0% of chitosan (control) and of 5.54 and 5.97% for the bread with 1 and 2% of chitosan, respectively. The loss of mass after oven baking is often associated with water loss. Thus, the result suggests that with the inclusion of chitosan, the bread retained more water, likely due to increased water absorption and water entrapment because of the hydrophilic nature of chitosan. It was found that hydrophilic bonds formed by hydroxypropyl methylcellulose and rice flour components increased water absorption (Rosell et al. 2011). However, the samples had water contents that did not differ significantly at P < 0.05, ranging from 26.46 to 27.25%.

Comparing the height of the dough and the height of the bread, the samples with 0% and 1% of chitosan obtained an oven-spring of 0.05 cm, while the samples with 2% obtained an oven-spring of 0.2 cm. The mass expansion factor is related to the acceleration of carbonic gas production in the first minutes of oven baking due to increased heating. The retention of this gas in the matrix formed by the polysaccharides could be responsible for this expansion, the more considerable the amount of gas produced, the higher the expansion factor. Thus, the results suggested that the increase of the expansion factor may be related to the increase of the retention of carbon dioxide and that chitosan can be responsible for hindering gas permeation (Akter et al. 2014). The formation of a network formed by crosslinks between chitosan and the amino-acids, catalyzed by the enzyme transglutaminase can also be responsible for increased gas retention (Hu et al. 2019).

The values obtained for ash analysis ranged from 1.1 to 1.3%, and there was no significant difference for P < 0.05 between the samples. It was observed that the addition of chitosan in the formulations increases the ash content obtained, possibly because this product still has residual calcium and sodium elements.

The pH value found among all bread formulations presented a significant difference (P < 0.05). Furthermore, it was evidenced that the addition of chitosan promoted the elevation of this parameter, with values varying from 5.75 to 6.07, suggesting that the cationic character of the added chitosan had an impact on pH. When dissolved, chitosan retains a hydrogen proton in its amine group and thus explains the increase in pH. Similarly, the bread acidity, which ranged from 2.63 to 1.75%, decreases because there are less free hydrogen protons in the 1% and 2% samples of chitosan.

Color

Color is a critical characteristic in bakery products because, together with texture and aroma, it contributes to consumers’ preference (Pu et al. 2019). According to Table 3, it is possible to observe that there is a significant difference for the parameter lightness (L*) when comparing the crust with crumbs. For all the samples, the values of L* of the crust were superior to those of the crumbs. Regarding the parameter a* (green–red transition), the values of the crust were higher than those of the crumbs. A significant difference for P < 0.05 was found for a* parameter. However, the sample with 1% of chitosan had the lowest values of a*. Considering the parameter b* (blue-yellow transition), It is observed that all values are higher at the crust than the crumbs. There was no significant difference for P < 0.05 of the values of b* found in the crust of the samples with 1% and 2% of chitosan, however, these same samples differed significantly in the values of b* found in control samples. The typical brown color of bread is attributed to Maillard reactions. The increased heat at the bread surface makes available more sugars and amino-acids for Maillard reactions. The latter products of the Maillard reaction cause the formation of brown pigment in the advanced stage of the reaction and, thus, less luminosity (Morales and Van Boekel 1998). Thus, the browning index was determined for all samples. From results, higher browning indexes were found for red rice bread with no chitosan. The bread added with 1% and 2% chitosan resulted in less brown products than the 0% chitosan sample. This result suggests that although chitosan participates in the Maillard reaction with the carbonyl and amino groups, the Maillard reaction might be incomplete, and thus the formation of final browning compounds is reduced. While studying the Maillard reaction between chitosan-glucose complexes, it was also found intermediate browning products and suggested incomplete reaction (Kosaraju et al. 2010). Another hypothesis could be related to the availability of amino-acid for the Maillard reaction because it is known that transglutaminase crosslinks those molecules and increases its molecular weight. Thus, those amino-acids become no longer available for the Maillard reaction. Because the same amount of transglutaminase was used on all samples, the amino-acid availability should be the same on all samples. However, a reduction on the browning index was found, suggesting that chitosan also participates in the Maillard reaction, although with incomplete browning formation. The crust presented much higher browning index values than crumbs, which is generally attributed to the heat exposure of the bread surface leading to more Maillard reactions.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients of the instrumental textural properties

| Moisture | Firmness | Cohesiviness | Chewiness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 28.520* | 6.356* | 0.409* | 2.791* |

| T | − 1.115* | 1.749* | − 0.036* | 0.173 |

| CC | − 0.664 | 2.030 | 0.053 | 1.602* |

| T × CC | 0.141 | 0.099 | − 0.01 | − 0.181 |

| R2 | 72.22 | 91.11 | 85.49 | 74.99 |

| Fcalc | 952 | 262 | 170 | 88.37 |

| p | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

*Regression coefficient is significant for a P < 0.05

Moreover, analyzing the parameter delta E, which is attributed to color variation, it was found, surprisingly, that samples with chitosan are the most similar to wheat bread.

Specific volume

The specific volume values found in the bread presented a significant difference between them for a P < 0.05. These values ranged from 1.64 to 1.48 cm3 g−1, which corresponds to an increase in bread density with increasing chitosan. The specific volume of wheat bread is significantly higher, which could be related to gas retention and, consequently, lower density. The gluten-free bread specific volume was unexpected because the water content was similar between samples. Thus, the hypothesis of a network that was able to retain more gas within the dough would have created higher specific volumes after baking. This network would have reduced the diffusion ability for the gas to permeate the starchy food, and thus the gas would have created a more porous structure (Lisboa et al. 2019). However, this result suggests that even though a network able to retain gas is possible, the excessive cross-linking could have created an over-strong dough and thus a bread with lower specific volume.

The improvement of gluten-free bread using rice flour and transglutaminase also reported adverse effects of excessive concentration of transglutaminase (Gujral and Rosell 2004). However, the amount of transglutaminase used was 0.5%, which is considered optimal for wheat bread (Basman et al. 2002). Possibly the inclusion of chitosan could have extended the transglutaminase reactions, and a lower optimal transglutaminase concentration should have been used. Another hypothesis could be the interference of chitosan on the yeast fermentation resulting in less carbon dioxide formation. To support such a hypothesis is the antimicrobial properties of chitosan that inhibits the growth of yeast (Shibata et al. 2018).

Rheological properties

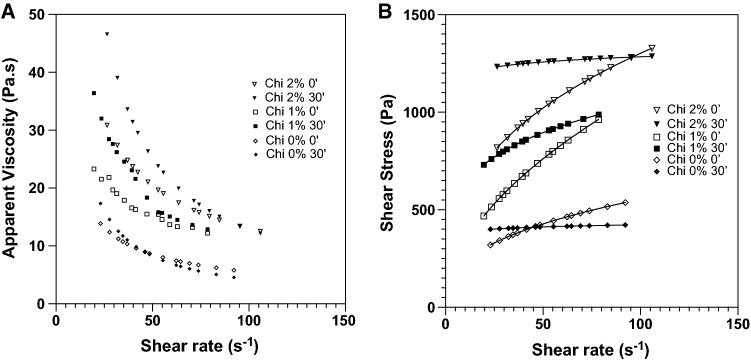

Dough rheological properties were assessed using rotational tests with a controlled shear rate. The measurements were performed immediately after complete mixing and repeated after the fermentative process. These measurements were performed to test the possible crosslinking between chitosan and transglutaminase within the dough. Figure 1 displays the flow curves of all doughs after complete mixing and after the fermentative process, which indicates the relationship between viscosity and shear rate and the dependency of chitosan concentration and mixing time. Apparent viscosity drops with shear rate revealing all dough fluids are pseudo-plastic with shear-thinning behavior. The pseudo-plastic behavior is often found on solutions composed of high molecular weights macromolecules along with much smaller molecules. Thus, at low shear rates, the dough will present several macromolecular entanglements that will result in large resistance to flow. However, at increasing shear rate, such macromolecules tend to be more aligned with the direction of the shear resulting in less resistance to flow (Lima et al. 2018).

Fig. 1.

Flow curves for gluten-free bread dough, before and after fermentation (0′ and 30′), and with chitosan concentrations of 0% (filled daimond), 1% (filled square), 2% (inverted traiangle)

Further analysis reveals an increase in the viscosity for the same shear rate after the fermentative process. This increase is true for all samples, but more evident for the dough with 1% and 2% of chitosan. On the one hand, viscosity increases simply because of chitosan concentration. However, the viscosity increase after the fermentation period is much higher at 1% and 2% of chitosan than at 0%. Thus, this increase suggests a possible crosslink between chitosan and transglutaminase, as suggested before, occurring during the fermentation period. The mechanism by which the viscosity would be increased is explained by the increase in the mean diameter of chitosan fibers due to crosslinking and, consequently, more entanglements among dough macromolecules. (Tian et al. 2016) while studying the crosslink of collagen with glutaraldehyde also found increases in viscosity for the same shear rate, and similarly to our work, a similar viscosity between samples at high shear rates.

Supplementary Table S1 presents the estimated coefficient for the rheological models applied to our experimental data. Considering the yield stress given by the Bingham model, results reveal an increasing tendency with chitosan concentration after the fermentation process. Since yield stress reflects the required stress for the fluid to start the flow, this increase suggests more entanglements are present and thus a more solid-like behavior when no shear is applied. Furthermore, Ostwald-waele flow indexes confirm the shear thinning behavior observed on Fig. 1 because the “n” values are all below 1. Comparing the “n” values before and after the fermentation period, a reduction is observed. A reduction on flow index was was also found collagen crosslink with glutaraldehyde (Tian et al. 2016).

Texture analysis

The effect of staling on the instrumental texture profile of the bread with the addition of chitosan and transglutaminase enzyme was studied throughout five days. Table 2 shows the results of the instrumental texture and moisture of the bread on the five days.

Table 2.

Texture parameters of gluten-free bread formulated with chitosan and transglutaminase enzyme

| Texture parameter | Chitosan (%) | Time (days) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Moisture (%) | 0 | 29 ± 1.2 | 24.7 ± 0.8 | 24.8 ± 0.5 | 24.2 ± 0.1 | 22.97 ± 0.5 |

| 1 | 26.9 ± 0.7 | 24.2 ± 0.8 | 25.17 ± 0.2 | 24.93 ± 0.4 | 23.47 ± 0.3 | |

| 2 | 28.6 ± 0.5 | 24.4 ± 0.2 | 21.93 ± 0.4 | 25.6 ± 0.2 | 22.93 ± 0.1 | |

| Firmness (N) | 0 | 12.25 ± 0.35 | 10.33 ± 0.17 | 15.27 ± 0.45 | 13.98 ± 0.42 | 14.92 ± 0.32 |

| 1 | 9.36 ± 0.28 | 11.72 ± 0.22 | 12.11 ± 0.20 | 14.46 ± 0.46 | 15.06 ± 0.29 | |

| 2 | 6.92 ± 0.80 | 14.65 ± 0.30 | 17.71 ± 0.32 | 19.43 ± 0.26 | 20.68 ± 0.45 | |

| Cohesiviness | 0 | 0.415 ± 0.3 | 0.296 ± 0.3 | 0.327 ± 0.5 | 0.334 ± 0.1 | 0.200 ± 0.3 |

| 1 | 0.453 ± 0.2 | 0.316 ± 0.5 | 0.243 ± 0.1 | 0.246 ± 0.1 | 0.276 ± 0.2 | |

| 2 | 0.492 ± 0.2 | 0.394 ± 0.7 | 0.371 ± 0.3 | 0.278 ± 0.2 | 0.268 ± 0.1 | |

| Chewiness (N) | 0 | 2.84 ± 0.25 | 3.03 ± 0.15 | 4.95 ± 0.31 | 4.64 ± 0.45 | 2.96 ± 0.28 |

| 1 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 3.67 ± 0.10 | 2.91 ± 0.23 | 3.53 ± 0.43 | 4.12 ± 0.22 | |

| 2 | 5.97 ± 0.35 | 5.72 ± 0.30 | 6.51 ± 0.40 | 5.36 ± 0.24 | 5.49 ± 0.47 | |

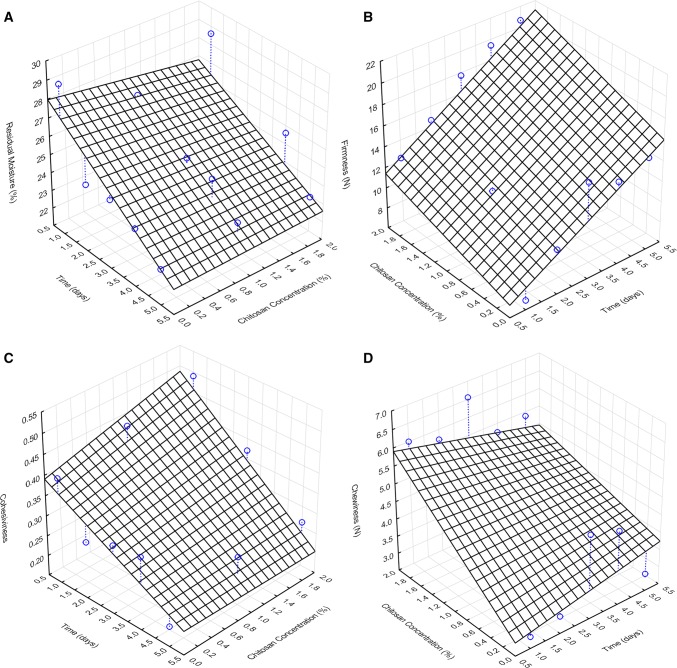

The moisture loss of the bread is related to the staling and thus the shelf life. Therefore it is important to understand the water-holding capacity of the produced bread. Analyzing the results (Fig. 2a), it was observed that there was a decrease during the five days with values varying between 22.93 and 29.2%. This same behavior was reported by (Lafarga et al. 2013)that obtained variations between 41.10 and 44.26% in moisture in bread containing 1% of chitosan during storage of 5 days. The difference can be justified by the amount of water used in the baking, as well as the use of wheat flour instead of rice flour which absorbs more water. Bread without chitosan lost 1.29%/day, whereas with 1% of chitosan it lost 0.613%/day and with 2% of chitosan it lost 1.04%/day. These results indicate that chitosan leads to an increased water-holding capacity of the bread, possibly because of the presence of hydroxyl groups which forms hydrogen bonds with water, thus reducing moisture migration. The moisture loss on bread without chitosan suggests that rice flour has low water retention capacity. Additionally, the presence of chitosan in the bread crust may serve as an additional barrier to the permeation of water vapor (Medina et al. 2019).

Fig. 2.

Surface plots of the influence of chitosan concentration and storage time on (a) Residual moisture b Firmness c Cohesiveness d Chewiness

Firmness is defined as the force required to compress the food with the molars, at the first bite. Considering Fig. 2b, values on the first day ranged from 12.25 N for 0% chitosan, 9.36 N, and 6.92 N for 1% and 2% chitosan, respectively. On the final day, the firmness values were 14.92 N, 15.06 N, and 20.68 N for 0, 1%, and 2% chitosan, respectively. These results were higher than those reported by (Lafarga et al. 2013) that obtained values of 2.94 N for bread added of 1% of chitosan on the first day and 5.2 N on the fifth day. Thus, the addition of chitosan increases the bread firmness, both in the concentration of 1% and 2% when compared to the control sample. This increase could be attributed to an increase in intermolecular interactions within the bread caused by transglutaminase induced crosslinks in the protein/chitosan matrix. However, this result may also be related to the lower specific volume of both chitosan bread when compared to the control. Throughout the storage days, the staling of the bread is evident by the increase of the bread firmness. In bread formulated with rice flour obtained through three types of grinding, an increase of firmness was also observed (Yan et al. 2019). Control bread had a firmness increase rate of 3.2 N/day, while bread added with chitosan had rates of 1.4 N/day and 0.9 N/day for samples with 1% and 2%, respectively. This result may be related to the retention of more water molecules next to the polymer chains. Those water molecules interrupt possible secondary bonds between the polysaccharide chains reducing the rate of firmness increase.

Food cohesiveness refers to the strength of the bond between its constituents. The initial values of cohesiveness (Fig. 2c) were 0.41 for the control bread and 0.45 and 0.49 for samples with 1% and 2% of chitosan, respectively. When added, chitosan provides an increase in the cohesiveness of the bread on the first day. Analyzing the effect of storage, the samples loose cohesiveness at similar rates, -0.038/day for control, -0.043/day and -0.058/day for 1% an 2% of chitosan. In a study on bread formulated with microbial transglutaminase and strong, medium, and weak flours, it was reported that the elasticity and cohesion of bread decreased according to the formulation and the storage time (Boukid et al. 2018). It was also pointed out that the increase in firmness provides less cohesive bread during storage (Boukid et al. 2019). The observed results suggest that the interaction between chitosan and the transglutaminase enzyme through covalent bonds with the proteins contained in the rice flour used in the formulations results in bread with lower binding forces over time.

The chewiness is the energy required to disintegrate the food until it is swallowed. Chewiness (Fig. 2d) values on the first day were 2.84 N for control samples and 4.2 N and 6.0 N for the samples with 1% and 2% chitosan, respectively. In gluten-free bread added with different amounts of transglutaminase enzyme, (Gusmão et al. 2019) reported values between 2.80 and 4.52 N. According to the authors, the addition of the enzyme transglutaminase increases the chewing of the bread requiring a more considerable masticatory effort when compared to non-enzyme gluten bread. In our work, for all samples, chewiness revealed to be stable throughout the days. These results were expected because samples with higher firmness presented low cohesiveness. Chitosan may delay the increase in firmness and chewiness, as well as the decrease in the cohesiveness of rice flours, possibly due to water retention that functions as a plasticizer within the crumb structure (Berta et al. 2019). The results obtained from the texture parameters of the bread shows that the addition of chitosan has the detrimental effect of increased firmness but slows down the increase of this parameter due to higher water retention that maintains the structure plasticized for more extended periods.

Mathematical modeling of textural properties

Mathematical modeling of the instrumental textural results during staling is presented in Table 3. Results were modeled using a first-order polynomial equation considering the storage time and the chitosan concentration as independent variables. Results revealed that storage time is significant (P < 0.05) for the moisture content, firmness, and cohesivity, while chitosan concentration is only significant to chewiness.

Conclusion

Gluten-free bread with the addition of red rice flour, chitosan, and transglutaminase enzyme was successfully obtained with similar properties to other commercial products. The inclusion of chitosan and the action of the enzyme transglutaminase presented alterations on the bread structure. From results, evidence of a stabilizing network could be attributed to the action of the transglutaminase enzyme with chitosan. However, some detrimental effects could also be attributed to the presence of chitosan, which could have reduced the extension of the yeast fermentation resulting in bread with low specific volume and, therefore, with higher firmness and chewiness.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akter N, Khan RA, Tuhin MO, Haque ME, Nurnabi M, Parvin F, Islam R. Thermomechanical, barrier, and morphological properties of chitosan-reinforced starch-based biodegradable composite films. J Thermoplast Compos Mater. 2014;27:933–948. doi: 10.1177/0892705712461512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida RLJ, dos Santos Pereira T, de Andrade Freire V, Santiago ÂM, Oliveira HML, de Sousa Conrado L, de Gusmão RP. Influence of enzymatic hydrolysis on the properties of red rice starch. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;141:1210–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.O.A.C . Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. 20. Rockville: AOAC international; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Basman A, Köksel H, Ng PK. Effects of increasing levels of transglutaminase on the rheological properties and bread quality characteristics of two wheat flours. Eur Food Res Technol. 2002;215:419–424. doi: 10.1007/s00217-002-0573-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berta M, Koelewijn I, Öhgren C, Stading M. Effect of zein protein and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose on the texture of model gluten-free bread. J Texture Stud. 2019;50:341–349. doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukid F, Carini E, Curti E, Bardini G, Pizzigalli E, Vittadini E. Effectiveness of vital gluten and transglutaminase in the improvement of physico-chemical properties of fresh bread. LWT. 2018;92:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.02.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boukid F, Carini E, Curti E, Pizzigalli E, Vittadini E. Bread staling: understanding the effects of transglutaminase and vital gluten supplementation on crumb moisture and texture using multivariate analysis. Eur Food Res Technol. 2019;245:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00217-018-3135-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, et al. Transglutaminase-catalyzed preparation of crosslinked carboxymethyl chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose/collagen composite membrane for postsurgical peritoneal adhesion prevention. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;201:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcea M, Narducci V, Turfani V, Aguzzi A. A survey of sodium chloride content in italian artisanal and industrial bread. Foods. 2018;7:181. doi: 10.3390/foods7110181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho MS, De Las Mercedes Salas-Mellado M. Effects of substituting chia (Salvia hispanica L.) flour or seeds for wheat flour on the quality of the bread. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2015;60:729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.10.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira S, et al. Physicochemical, morphological and antioxidant properties of spray-dried mango Kernel starch. J Agric Food Res. 2019;25:100012. [Google Scholar]

- Gharibzahedi SMT, Roohinejad S, George S, Barba FJ, Greiner R, Barbosa-Cánovas GV, Mallikarjunan K. Innovative food processing technologies on the transglutaminase functionality in protein-based food products: trends, opportunities and drawbacks. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018;75:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gharibzahedi SMT, Yousefi S, Chronakis IS. Microbial transglutaminase in noodle and pasta processing. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59:313–327. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1367643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal G, Mehta S. Effect of chitosan on physicochemical and rheological attributes of bread. Food Sci Technol Int. 2019;25:198–211. doi: 10.1177/1082013218814285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral HS, Rosell CM. Functionality of rice flour modified with a microbial transglutaminase. J Cereal Sci. 2004;39:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2003.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gusmão TAS, de Gusmão RP, Moura HV, Silva HA, Cavalcanti-Mata MERM, Duarte MEM. Production of prebiotic gluten-free bread with red rice flour and different microbial transglutaminase concentrations: modeling, sensory and multivariate data analysis. J Food Sci Technol. 2019;56:2949–2958. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, et al. Modification of chitosan grafted with collagen peptide by enzyme crosslinking. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;206:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaraju SL, Weerakkody R, Augustin MA. Chitosan—glucose conjugates: influence of extent of Maillard reaction on antioxidant properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:12449–12455. doi: 10.1021/jf103484z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafarga T, Gallagher E, Walsh D, Valverde J, Hayes M. Chitosan-containing bread made using marine shellfishery byproducts: functional, bioactive, and quality assessment of the end product. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:8790–8796. doi: 10.1021/jf402248a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima DB, Almeida RD, Pasquali M, Borges SP, Fook ML, Lisboa HM. Physical characterization and modeling of chitosan/peg blends for injectable scaffolds. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;189:238–249. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa HM, Araujo H, Paiva G, Oriente S, Pasquali M, Duarte ME, Mata MEC. Determination of characteristic properties of mulatto beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) during convective drying. J Agric Food Res. 2019;25:100003. doi: 10.1016/j.jafr.2019.100003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins ANA, de Bittencourt Pasquali MA, Schnorr CE, Martins JJA, de Araújo GT, Rocha APT. Development and characterization of blends formulated with banana peel and banana pulp for the production of blends powders rich in antioxidant properties. J Food Sci Technol. 2019;25:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03999-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina E, Caro N, Abugoch L, Gamboa A, Díaz-Dosque M, Tapia C. Chitosan thymol nanoparticles improve the antimicrobial effect and the water vapour barrier of chitosan-quinoa protein films. J Food Eng. 2019;240:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mert ID. The applications of microfluidization in cereals and cereal-based products: an overview. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;64:1–18. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1555134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitschka P. Simple conversion of Brookfield RVT readings into viscosity functions. Rheol Acta. 1982;21:207–209. doi: 10.1007/BF01736420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MM, Heinbockel M, Dockery P, Ulmer H, Arendt EK. Network formation in gluten-free bread with application of transglutaminase. Cereal Chem. 2006;83:28–36. doi: 10.1094/CC-83-0028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morales F, Van Boekel M. A study on advanced Maillard reaction in heated casein/sugar solutions: colour formation. Int Dairy J. 1998;8:907–915. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(99)00014-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morreale F, Garzón R, Rosell CM. Understanding the role of hydrocolloids viscosity and hydration in developing gluten-free bread. A study with hydroxypropylmethylcellulose. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;77:629–635. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pu D, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Sun B, Ren F, Chen H, He J. Characterization of the aroma release and perception of white bread during oral processing by gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry and temporal dominance of sensations analysis. Food Res Int. 2019;123:612–622. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakkhumkaew N, Pengsuk C. Chitosan and chitooligosaccharides from shrimp shell waste: characterization, antimicrobial and shelf life extension in bread. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2018;27:1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s10068-018-0332-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro M, et al. Effect of in situ gluten-chitosan interlocked self-assembled supramolecular architecture on rheological properties and functionality of reduced celiac-toxicity wheat flour. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;90:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roman L, Belorio M, Gomez M. Gluten-free breads: the gap between research and commercial reality. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2019;18:690–702. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell CM, Yokoyama W, Shoemaker C. Rheology of different hydrocolloids–rice starch blends. Effect of successive heating–cooling cycles. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;84:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.11.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata K, et al. Promotion and inhibition of synchronous glycolytic oscillations in yeast by chitosan. The FEBS journal. 2018;285:2679–2690. doi: 10.1111/febs.14513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Z, Duan L, Wu L, Shen L, Li G. Rheological properties of glutaraldehyde-crosslinked collagen solutions analyzed quantitatively using mechanical models. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2016;63:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J-K, Wu L-X, Qiao Z-R, Cai W-D, Ma H. Effect of different drying methods on the product quality and bioactive polysaccharides of bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) slices. Food Chem. 2019;271:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.